Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

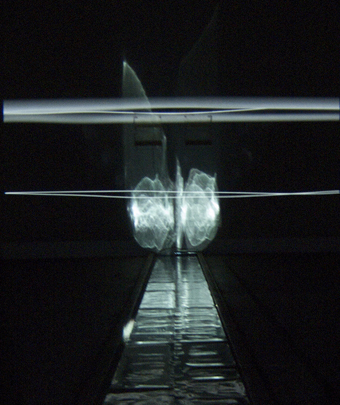

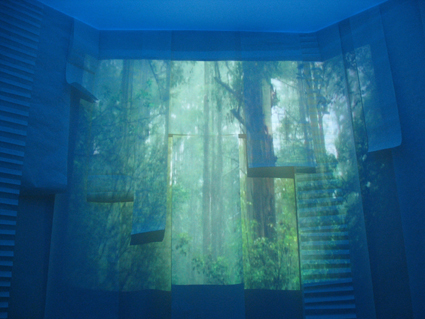

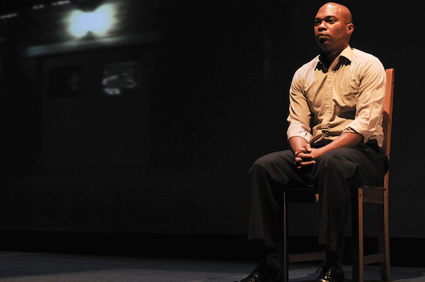

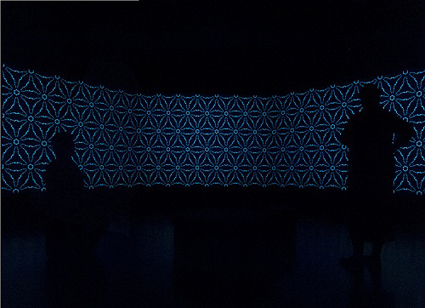

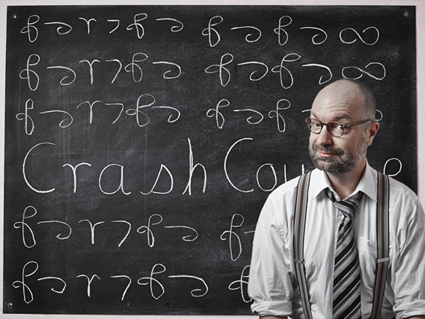

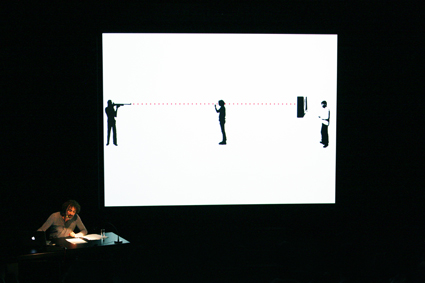

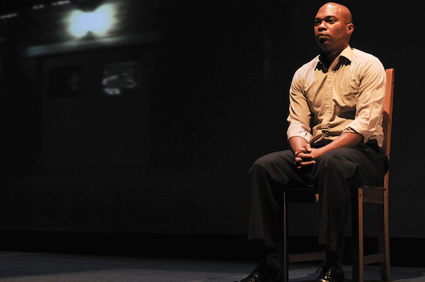

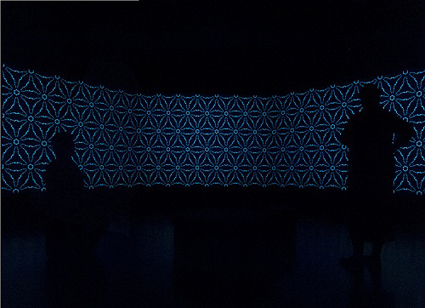

Lemi Ponifasio, Stones In Her Mouth

photo MAU

Lemi Ponifasio, Stones In Her Mouth

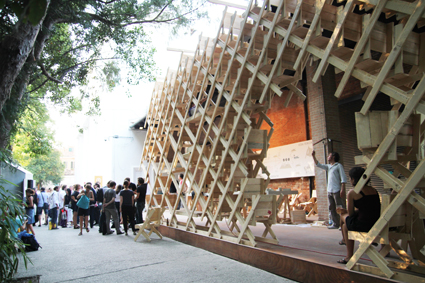

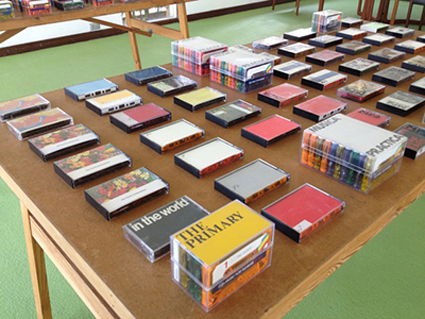

A beaming Lisa Havilah, director of Carriageworks, the contemporary multi-arts centre located in Sydney’s Redfern, proudly guides me through the proof sheets of her 2014 program prior to its launch. It’s abundantly evident that Havilah has, over several labour intensive years, incrementally established a clear sense of purpose, identity and, not least, continuity, confirming that her programing is underpinned by a firm vision. The venue has doubled in size and attracted 400,000 visitors in 2013.

It’s especially pleasing that Havilah has resolutely committed to the notion of Carriageworks as a contemporary arts space, not an entertainment centre, like the Sydney Opera House, now awash with stand-up comedians and indie bands. Havilah’s program cogently reflects and nurtures the diversity of contemporary art practices—through long-term projects and commissions, off-site residencies and an ever-expanding network of partnerships with like-minded organisations.

What stage is this in the evolution of Carriageworks under your direction?

2014 will be the third year of our re-imagining of what Carriageworks is going to be and the third year of implementing what we think is quite a distinctive artistic vision for the organisations resident here and for the overall institution. I think this makes it distinctive from other major cultural institutions across Sydney, but also across the country in that Carriageworks has a real multi-arts contemporary focus, and a focus on cultural diversity and contemporary urban practice as well. The program reflects the cultural demographic of Sydney and supports the development of work that really does move across art forms in interesting ways. 2014 also continues our commitment to commissioning and presenting work of scale that meets the architecture of Carriageworks.

These are works that occupy the foyer and the large performance spaces?

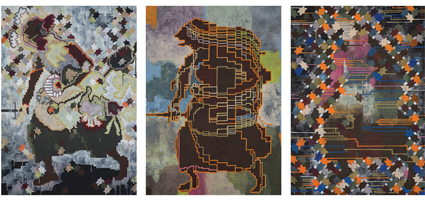

This wholly new direction started with Travelling Colony, the large-scale Brook Andrew commission [painted caravans containing video interviews with Redfern Indigenous inhabitants in the Carriageworks foyer], then Song Dong [Waste Not, a massive foyer installation], Ryoji Ikeda’s Test Pattern (No5), MAU’s Birds with Skymirrors and Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s dance works [Cesna and En Atendant]. These are epic works that speak to and reflect back on contemporary life but at the same time are of a scale that pays respect to the scale of the building and the history and the context within which the work is presented. This is always a key factor in how we think about programming. We are located in Redfern, a place that has a strong political and social history and is undergoing very significant change. And that’s also a hallmark of Carriageworks—the scale of change that we have driven in part but, in return, are also experiencing because the artistic program is driving it. All of our success emerges from the content, commitment and quality of our artistic program with its artists.

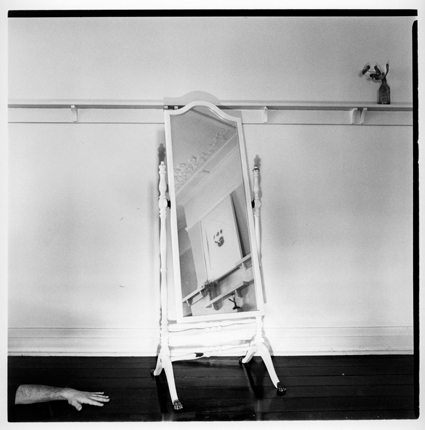

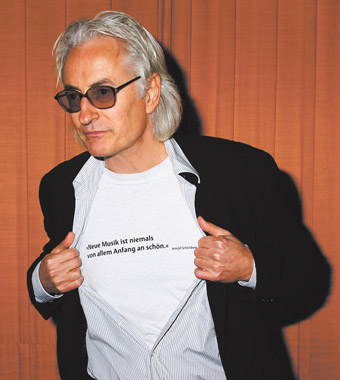

Christian Boltanski

courtesy Carriageworks

Christian Boltanski

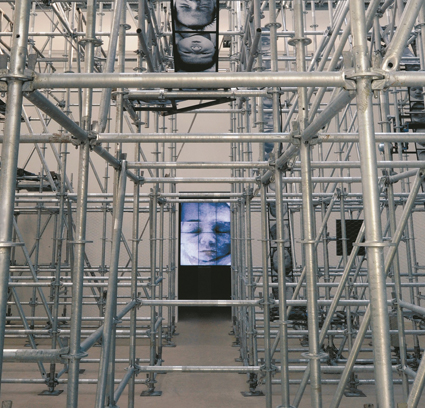

Your 2014 program opens with a huge installation by French sculptor, photographer, painter and filmmaker Christian Boltanski that mimics a printing press.

It’s 40 metres long and 10 metres high and will occupy all of the foyer space. You’ll be able to walk around and through it and also play a game of chance.

As part of your annual social history program, you’ll have an exhibition featuring the Aboriginal Progressive Association and its activities and achievements prior to World War II.

Yes, and one of our most important projects with the Indigenous community is a partnership with Alexandria Park Community School where we’re establishing a full-time artist’s studio within the school. We’ll invite an Aboriginal artist to be in residence there each of three years. The first will be the incredible contemporary dancer/physical performer Ghenoa Gela followed by Tony Albert, then Microwave Jenny [pop/folk/jazz duet Tessa and Brendan Boney].

You’re clearly committed to long-term programming.

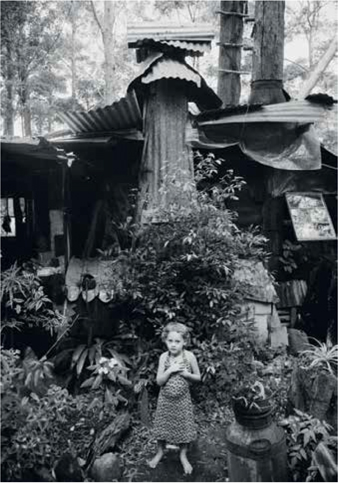

That’s another key driver in terms of how we develop the program. We were so excited to be able to bring Lemi Ponifasio’s Birds with Skymirrors here in 2013. We now have a long-term partnership with Lemi and MAU in which we’ll co-commission a new work from him over the next three years and hopefully that relationship will develop into the future. Most often, you’d experience a work from this company but then not see anything else from them for 10 years. This way we can really work with Lemi to build audiences in Sydney for his work who can see how the practice builds over a number of years.

You’ve also programmed Sydney Chamber Opera, Perth composer Cat Hope (working with visual artist Kate McMillan) and the UK-based Australian ensemble Elision. That’s good news for new music.

That’s been one of the things I’ve loved most about our program in 2013, with Sydney Chamber Opera, Michael Kieran Harvey and the amazing Jack Quartet from New York. This will be the first time we’ve included Sydney Chamber Opera’s work as part of our own artistic program. That’s quite a significant increase in our support to that company. My practice doesn’t emerge from music but I’ve loved engaging with those artists. We’re looking to continue to build that program.

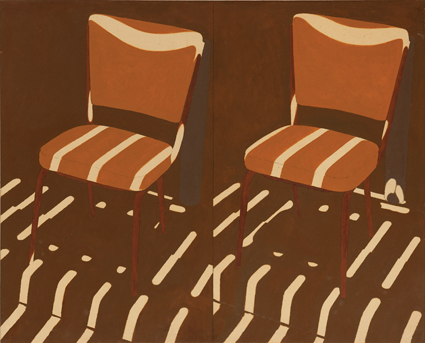

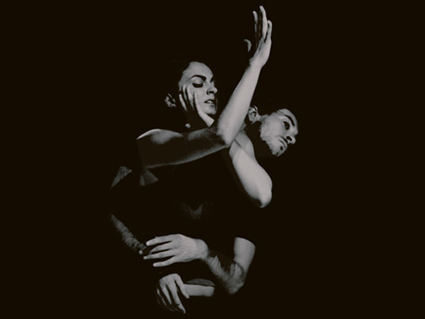

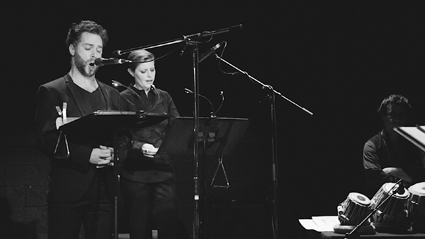

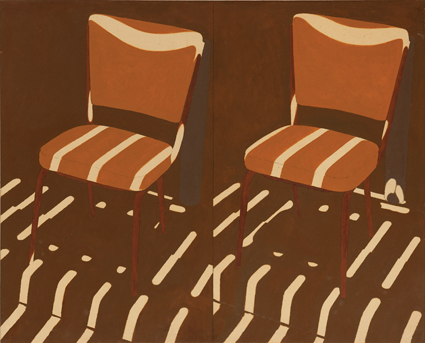

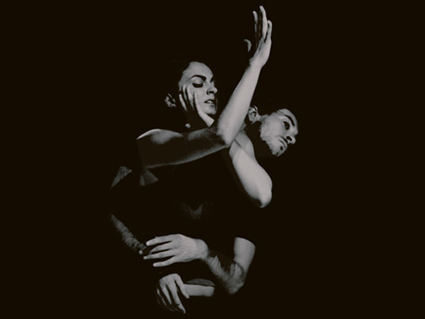

Shanghai Bolero

courtesy Carriageworks

Shanghai Bolero

Dance is a form you’ve committed to strongly. Next year you have Compagnie Didier Theron, which is quite a coup.

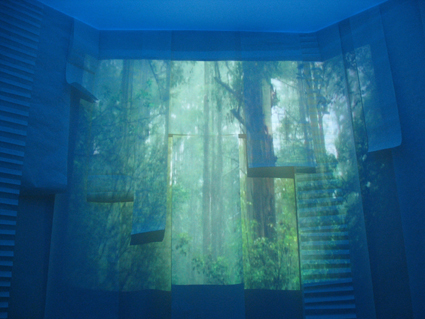

This year we partnered with Brisbane Festival to present the amazing Doku Rai and Fight the Landlord. We proposed Didier’s company and we were lucky they concurred. It’s the first time he’s ever presented a work in Australia: three radically different responses to Ravel’s Bolero in the one show.

You come from a visual arts background. What appeals to you in dance?

My passion for it started at Campbelltown Arts Centre where dance programmer Emma Saunders and I curated What I Think About When I Think About Dancing (2009), looking at the intersections between visual arts and contemporary dance. I really loved the way artists in the independent dance sector worked. It’s the visual and the repetitive nature of dance that appeals, and the exactness and discipline. A company like Rosas [creates] a visual artwork that moves in an incredible way over an extraordinary duration. I think that’s one of the most incredible experiences that I’ve had in a theatre ever.

You also have Force Majeure, resident dance company at Carriageworks, doing several shows.

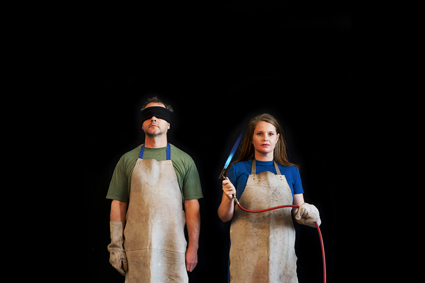

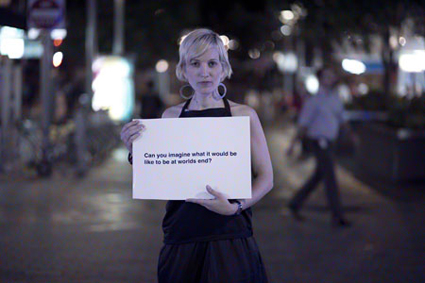

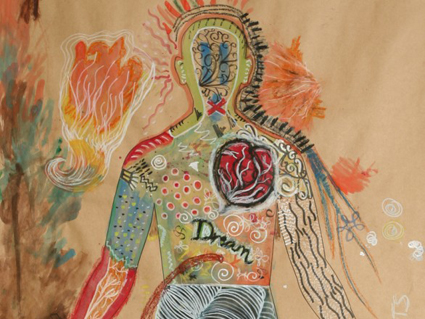

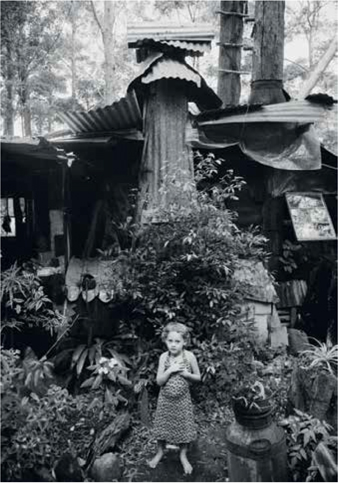

At the end of the year we’re co-commissioning and presenting Obscura with the company; it’s a major work by Byron Perry. In other dance, from MAU we’ll have the very beautiful Stones in her Mouth, which just opened at Red Cat in Los Angeles to really amazing reviews. We’ve established a relationship with the Keir Foundation and Dancehouse to establish the Keir Choreographic Awards which will invest in new commissions and a cash prize. We also have a multi-year partnership with NAISDA as well, presenting their end of year work and doing residencies in their Central Coast [facility]. And we have a Ken Thaiday Snr exhibition, featuring headdresses and performance from the Tiwi Islands, the Sydney Dance Company’s New Breed, works by four choreographers, two from outside the company; the NAISDA end of year show; and a new show, Choreography, by Garry Stewart with NIDA students.

As part of our policy we co-commission or co-present a number of works with resident companies every year. With Performance Space we’re doing the Ken Thaiday Snr show, as a co-commission, a work by electronic media artist Pia Van Gelder and a multi-sensory environment by Cat Hope and Kate McMillan. We’re working much more in partnership with Performance Space in 2014.

What is Carriageworks’ role in the Biennale of Sydney?

We’re a major venue partner. This is a first which ranks us with AGNSW and the MCA and brings the Biennale to this part of town. We’re presenting around 25 works over Bays 22-24 and we’re commissioning a major new work by the Berlin-based English artist Tacita Dean. It’s Biennale director Juliana Engberg’s idea but we’re producing the work for them and working directly with Tacita Dean.

You also have events focused on food, with a co-production, The Serpent’s Table, with Griffin Theatre Company featuring chef Adam Liaw and others, a two-day sustainable food event and Carriageworks is now managing the Eveleigh Market.

And Kylie Kwong is our 2014 Carriageworks ambassador. It’s important the market is integrated into the precinct. Broadly, we have a commitment to excellence in contemporary arts and culture; whether that’s fashion or food or music or dance. We always try to make interesting intersections.

You’ll find more about the substantial 2014 Carriageworks’ program, including Back to Back’s Ganesh vs The Third Reich and New York-based durational performance artist Teching Hsieh (in partnership with UNSW College of Fine Arts)

Carriageworks 2014 program: www.carriageworks.com.au

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 18

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

There’s been quite an upsurge in discussion recently on the distribution and exhibition of Australian films, both in the traditional and online media and in sessions at various conferences. It’s a debate that’s been driven in part by continuing concern about the failure of many local films to reach their audiences, and in part by the potential for new and innovative methods to reach those audiences through digital distribution.

There’s been quite an upsurge in discussion recently on the distribution and exhibition of Australian films, both in the traditional and online media and in sessions at various conferences. It’s a debate that’s been driven in part by continuing concern about the failure of many local films to reach their audiences, and in part by the potential for new and innovative methods to reach those audiences through digital distribution.

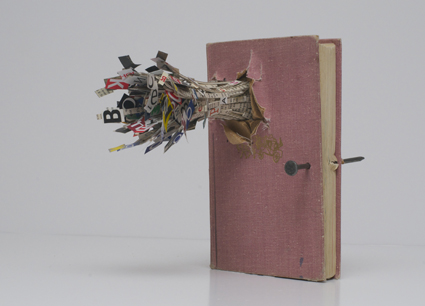

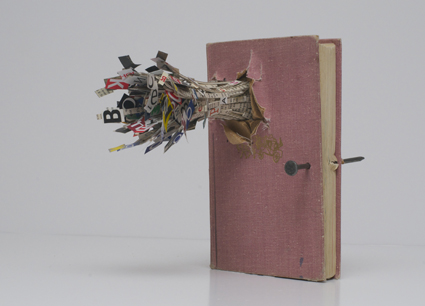

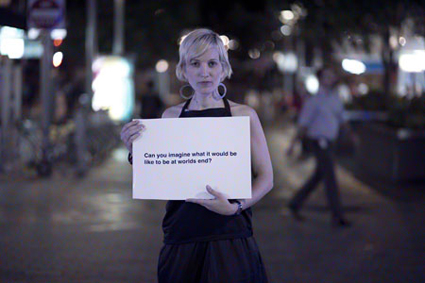

Now there’s a new entry into the debate, the essay Not at a Cinema Near You: Australia’s film distribution problem, which argues that “digital and innovative distribution can haul Australian films from the cultural margins into the mainstream,” and makes a cogent case for substantial change to the traditional methods, proposing instead “a new distribution model that can allow local films to expand their audiences and their revenues.”

In her essay, Lauren Carroll Harris argues that instead of requiring local films to have an Australian theatrical distributor as a pre-requisite for production funding, this stipulation should be expanded to include DVD, Video-on-Demand or non-theatrical, alternative distribution. This way, Harris says, “the distribution of small-budget releases would be diversified in circuits to which viewers are gravitating.”

As she says, “our film culture does not live in the motion-picture theatre, but in the audiences utilising it. . .other circuits are largely invisible because the mainstream media continues to measure Australian cinema solely according to box office sales and ratings.”

The essay contains a brief but sharp and focused history of film distribution in Australia, painting a rather depressing portrait of the current state of affairs in which, as Harris says, “not a single filmmaker or company has figured out how to distribute a film both widely and inexpensively, even with the near-revolutions in digital distribution.” She goes on to detail “the obstruction that Australian films face at the cinema, not to whinge, but to show the necessity for energetic online and non-theatrical distribution. Ancillary markets,” she writes, “are no longer ancillary, they are the markets. It is the cinema that is supplementary. However, we are yet to catch up with this reality: Australian films are released stillborn into a theatrical system that is not designed for them and that therefore reduces their ability to compete.”

As Harris explains, the federal government’s funding body, Screen Australia, has a policy which consists “almost entirely of efforts to boost production and development through direct investment and tax rebates for private investors,” requiring the involvement of “a theatrical distribution company to provide both a massive injection of production funds and to release films into the market on completion.” This, she argues, “hands a disproportionate level of control to distributors who, despite their expertise, are innately conservative and risk-averse in predicting audiences’ desires.”

While Screen Australia has a “sorely needed” Innovative Distribution Program (set to expire this year with so far no plan to replace it), films that signed with non-traditional distributors who are part of this program are precluded from support—“an obvious policy contradiction that is yet to be resolved,” and one that an increasing number of lower-budget, innovative filmmakers are complaining about.

“Rather than leaving distribution to commercial distributors,” Harris asks, “might not an independent committee of distributors (theatrical and non-theatrical), publicists and expert policy makers advise on film projects, from pre-production onwards, on how to build market attachment packages aimed at reaching increasingly dispersed audiences? This distribution advisory board would provide information and experience that right now is mostly in the private sector, create estimates of potential box office and ancillary market performance, suggest the best release platforms for titles in development, offer advice on marketing schemes, and generally be a source of concrete knowledge on industry innovation in forward-thinking distribution.”

The essay provides a detailed assessment of the current distribution structure and provides case studies of films that have been successfully released theatrically and films that have failed and why, and compares and analyses these examples. It looks at self-distribution and at the bewildering possibilities offered by digital distribution, with detailed examples of success stories involving a number of different methods. There is, Harris believes, “a powerful case” to be made for “looking beyond the theatrical horizon towards a ‘handmade’ approach to distribution and marketing that takes equal account of non-theatrical circuits. The goal of a handmade distribution approach is to grow audiences for local content, increase filmmakers’ revenue share and refocus release strategies on the question of accessibility.”

At the recent Australian Directors’ Guild Conference, the session on “The Director as Distributor” looked at the opportunities and problems presented by the variety of means of self-distribution currently available. Moderated by Lauren Carroll Harris, the session highlighted self-distribution by two filmmakers: Bob Connolly, whose successful theatrical release of Mrs Carey’s Concert has become almost a legend (see Dan Edwards, p21), and Genevieve Bailey, a successful maker of many short films, who self-produced and self-released her feature documentary I Am Eleven, which screened for 26 weeks in Melbourne and in 46 cinemas nationally. “The most important element is the audience,” she said. “I really believed we could reach that really diverse audience that was out there, but you have to be willing to work like a crazy person. The reality is that a lot of excellent films are made and never get into a cinema, never get seen.”

Bailey explained how she’d timed the DVD release for Mother’s Day this year, and waited until she was happy with the website. The film had sold 2,000 copies in two weeks (it’s since sold a lot more). Bob Connolly released Mrs Carey’s Concert through Madman, “but we controlled the packaging and the production. And we got a very big advance! But we also put a lot of money into our website, and we’ve sold a lot of DVDs ourselves. We also put our other films on the website, and they’re ticking away very nicely.”

Also on the panel was Thomas Mai, formerly a producer and sales agent, who has been touring the world for five years, talking about the new tools available for filmmakers: crowd funding, social media networking and alternative means of distribution. Now settled in Australia, he received an Innovative Distribution Grant from Screen Australia, with Josh Pomeranz, to help filmmakers with these new tools. “We believe the answer lies with the audience, that you acquire this database of fans. (US doco maker) Robert Greenwald has 2.2 million people in his database. It’s fan dependent—you keep building that database from film to film. Find these people and keep them!”

In this essay, Lauren Carroll Harris has made a timely and important contribution to the ongoing and increasingly necessary debate about old and new film distribution. As she says, there is a “pressing need to re-think distribution as the vital way in which we conceive and reach out to our audience—and an urgent problem requiring a solution for Australian filmmakers.” Let’s hope her essay assists in achieving that solution.

Lauren Carroll Harris, Platform Papers, No 37, Not At a Cinema Near You, Currency House, Sydney, 2013. Platform Papers are available online at www.currencyhouse.org.au.

Courtesy of Currency House, RT has 5 copies of Not At a Cinema Near You to giveaway.

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 20

© Tina Kaufman; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

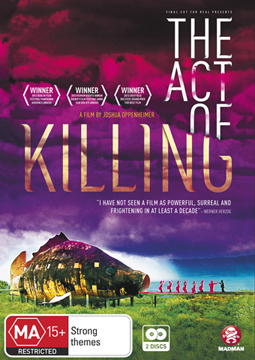

It was living in a dictatorship that cemented my love of documentaries. Thankfully, we don’t suffer under such a system, so documentaries in Australia will perhaps never carry quite the same charge they possess in some countries. But ruminations on the stark differences between the documentary world I encountered in China and Australia’s more staid factual realm have been bubbling away at the back of my mind since I returned home in 2011.

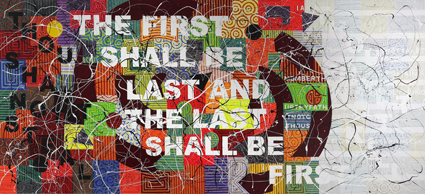

Independent Chinese documentaries are cheaply made and technically rough, but the best of this work is infused with a passion that held me transfixed. When I watched these films in cafes, galleries and studios in Beijing, I knew others in the audience felt the same way. So why don’t I get the same feelings here? Digital technologies were supposed to liberate filmmaking, but local documentaries feel like they’re getting less challenging and certainly more formulaic. These thoughts returned to the front of my mind recently with a debate initiated by Australian filmmaking legend Bob Connolly and the publication of Lauren Carroll Harris’ Platform Paper, Not at a Cinema Near You (Currency House). Both offered some provocative views on the structural problems besetting Australia’s documentary scene.

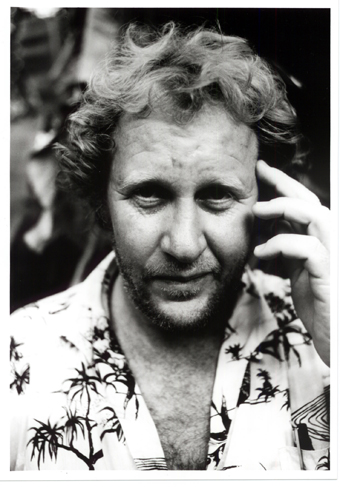

Back in August, Connolly used the occasion of a private screening of Sophia Turkiewicz’s new film, On My Mother, to make a speech problematising the state of Australian documentary funding. Connolly pointed out that almost all forms of Screen Australia funding are now contingent on broadcaster presales—with the result that a pair of commissioning editors at the ABC and SBS exercise enormous power over what documentaries are made. This situation is hardly conducive to diversity, and has been dire for the production of stand-alone feature-length documentaries.

Connolly’s comments are so self evident that the response of the ABC’s Head of Factual Programming, Phil Craig, was somewhat surprising. In an email, later published by Screen Hub, he told Connolly his speech was “utter bollocks” and challenged the veteran director to a head-to-head session at the next AIDC from which “only one of us walks out alive.” For Craig’s sake, I wouldn’t like to lay odds on who would emerge from such an encounter. He later backed down from this rather childish and belligerent stance, but his initial reaction is indicative of the profound resistance of some broadcast personnel to having their assumptions challenged.

Connolly’s comments are so self evident that the response of the ABC’s Head of Factual Programming, Phil Craig, was somewhat surprising. In an email, later published by Screen Hub, he told Connolly his speech was “utter bollocks” and challenged the veteran director to a head-to-head session at the next AIDC from which “only one of us walks out alive.” For Craig’s sake, I wouldn’t like to lay odds on who would emerge from such an encounter. He later backed down from this rather childish and belligerent stance, but his initial reaction is indicative of the profound resistance of some broadcast personnel to having their assumptions challenged.

The point of Connolly’s speech, as he himself later pointed out, was not to criticise the programming decisions of particular commissioning editors. It was to highlight the fact that broadcaster presales now represent virtually the only funding pathway for Australian documentary makers. Since the ABC and SBS are usually the only broadcasters in this country awarding such presales, this places enormous power in the hands of very few individuals and forces almost every project into the television template.

Breaking distribution barriers

Which brings me to Lauren Carroll Harris’ Platform Paper, Not at a Cinema Near You. Harris’ essay focuses on the similarly constricted realm of Australian theatrical distribution, although in this instance the restrictions are more related to commercial oligopolies. Like Connolly, she identifies the necessity of having a theatrical distributor attached to a film to garner Screen Australia funds as a problem for most Australian features. The nature of distribution in Australia means very few local features get any chance to compete fairly against the Hollywood fare dominating cinemas. Harris suggests some innovative ideas for diversifying distribution strategies, mainly revolving around the game-changing nature of digital technologies. Like Connolly, she suggests decoupling film funding from the severely limited distribution options prescribed under Screen Australia guidelines, and cites one of Connolly’s films, co-directed with Sophie Raymond, as an instructive example of how distribution can be done differently.

After their feature-length documentary Mrs Carey’s Concert successfully debuted at the Adelaide Film Festival in 2011, Palace offered Connolly and Raymond a distribution deal. As Harris details, even when these rare deals are forthcoming for Australian work, the terms mean that filmmakers are virtually guaranteed to see no returns, no matter how successful their theatrical run. So Connolly and Raymond rejected Palace’s offer, and organised their own release, initially through nine cinemas, which gradually grew to 70 nationwide.

Self-distribution

Self-distribution is a realistic option in an age when the prohibitive cost of making film prints is no longer necessary. Connolly and Raymond personally worked their screenings, conducting Q&As and selling DVDs. They spread the word among the education and classical music communities in which the film is set, and utilised the Australian Teachers of Media mailing list. They put together a soundtrack CD. They carefully and painstakingly cultivated their audience. The result was one of the most financially successful Australian documentaries in history. That still doesn’t add up to a whole lot of money, but maximising even minimal earnings is important if you’re a documentarian trying to make a living.

In this example, Harris also sees something potentially more empowering in the long run for both filmmakers and audiences. She writes:

“The filmmakers saw distribution as a way of creating the film culture they regard as possible and necessary…active audiences were encouraged to contribute to the kind of film culture they desired.”

To me this is the most exciting—and least realised—possibility afforded by the digital revolution. These technologies allow the possibility of bypassing some of the traditional gatekeepers of public culture to forge an audience more actively invested in what they are seeing. Admittedly, Mrs Carey’s Concert relied on an ABC presale to actually get made, but the filmmakers chose to bypass the oligopoly dominating Australian theatrical distribution to get their work into cinemas. And they took control of building their audience, rather than simply handing their work over to a major distributor with little financial incentive to promote Australian cinema of any kind, let alone documentaries.

Diversifying screen culture

If we’re truly passionate about documentaries as public stories, and not just television “content,” we should not only be making these films by whatever means necessary, but also building events and spaces—both physical and virtual —in which we can share them. Connolly’s arguments about diversifying funding channels for production are important, but any changes to funding criteria should work hand in hand with a more diversified and grassroots screening culture, vital to nurturing a more vibrant and engaged documentary culture. It’s no coincidence that one of the key publicists who helped Connolly and Raymond distribute Mrs Carey’s Concert was Kim Lewis, a veteran of the Filmmaker Co-ops that distributed documentaries and experimental films in most Australian capitals in the 1970s and 80s. The co-ops represent an example of grassroots, filmmaker-led distribution that is sadly lacking in contemporary times.

In fact, in our commercially driven and individualistic era, initiatives like the film co-ops seem like a distant dream. Yet within this history—our history—there lies a whole other way of making, distributing and thinking about films that has largely been forgotten. When I lived in China, Western filmmakers would sometimes smugly tell me that Chinese independents had a lot to learn about tailoring their films to the international environment. It seems to me we could learn—or perhaps relearn—more from them: about why we make documentaries, about building a culture from the ground up, and most importantly, about how our film culture can be so much more than a market. Connolly and Harris have ignited the debate—may it continue to smoulder in 2014.

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 21

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tiny Furniture

The difficulty of reviewing 2010’s Tiny Furniture in 2013 (just released in Australia on DVD) is that subsequent achievements and work of its writer-director-star Lena Dunham (namely the HBO show Girls and a much publicised multi-million dollar book advance) inevitably loom large over it.

Frequently cited as the work that convinced Judd Apatow to produce Girls, Tiny Furniture claimed the SXSW Film Festival Best Narrative Feature prize in 2010. Considered as a stand-alone work, the film is somewhat frustrating—all promise and no punch. As the precursor to a cult TV show and the early work of an influential filmmaker, it’s fascinating.

Like Dunham’s later work Girls, Tiny Furniture appears to be lightly fictionalised and semi-autobiographical in scope. Dunham plays Aura, a recent film theory graduate returning to her mother and sister’s New York apartment to the borderline ambivalence of both. Dunham’s artist mother, sister and house play their on-screen counterparts, which further blurs the lines between fiction and autobiography. Nursing a lightly bruised heart, Aura embraces her post-graduation ennui by haphazardly drifting into work as a host at a local restaurant, rekindling a semi-destructive childhood friendship, dabbling romantically in a semi-truncated fashion with both ‘internet famous’ Nietzschean Cowboy (Alex Karpovsky) and cute sous-chef Keith (David Call), while alienating family and friends.

Stylistically, the film is languid and thankfully eschews the strangely angled shots and experimental cutting techniques one might expect from a 23-year-old director. The gently wafting score of Teddy Blanks and assured cinematography of Jody Lee Lipes complement Dunham’s keen ear for dialogue and eye for the absurd in daily life. In the vein of Seinfeld and Woody Allen (both self-consciously referenced), and with a nod to the lo-fi naturalistic dialogue of ‘mumblecore,’ Tiny Furniture is not so much a plotted linear narrative as a collection of observations gathered from the viewpoint of a particular cultural time and place. Aura’s crippling lack of direction and ambition are given space to breathe rather than being arbitrarily used to drive a plot forward. The result is assembled into a collage onto which audiences can project their own meaning.

The film’s best passages are those that include family interactions, which enable Dunham’s strength with dialogue and fearlessness as an actor to show. Sadly, even as individual scenes shine (for example a scene in which Aura’s younger sister arrives in the middle of a fight between Aura and her mother only to snicker is one that siblings everywhere will recognise), the whole ensemble is less than the sum of its parts. Promising ideas thread through the film—Aura’s compulsive reading of her mother’s journals from the same life stage—but they jostle with more clichéd elements such as using asexual nudity as a proxy for vulnerability, or the funny-tragic death of a pet. As a result, the film feels uneven. Most frustratingly, intriguing characters emerge in Aura’s life but have no room to grow and so drop out of sight and relevance. The result is that even well realised characters feel like caricatures. Of these, Jemima Kirke shines as childhood friend and inspirational hot mess Charlotte (an earlier incarnation of Jessa played by the same actor on Girls).

Overall, Aura and Tiny Furniture are much less ambitious than Hannah and Girls. Made on a low budget (reported variously as between $25,000 and $50,000) the narrow framing and smaller scale are the film’s strengths. While the film, like Girls, has an overwhelmingly white cast drawn from Dunham’s personal network, the tighter focus of the film on the home life of a single character excuses this to a large degree.

Tiny Furniture is clear on what it is not. The film doesn’t frame Aura’s sexual dalliances as a proxy for a larger commentary on gender relations; there is no grand soliloquy on economic opportunities, or a catalysing moment through which Aura achieves anything like self-awareness or personal growth (although the mere existence of the film indicates very clearly that its creator has). Refreshingly, the film is free of moralising: it neither condemns nor celebrates the effects of wealth and drugs, instead it merely presents a world in which people have differing levels of access to both.

Overall, it’s worth a look, but it won’t sustain repeat viewing. If you like Girls, you’ll enjoy seeing the subtle differences and tracing how the bones of the ideas explored here evolved in a different format. If you don’t, you’ll see the same frustrating self-involvement on display. Creative professionals are often forced to mature professionally in the public eye, with their early work just a quick Google search away. Here, Lena Dunham need not worry—the film is exactly what it should be: the first steps of an intriguing filmmaker.

Tiny Furniture, writer-director Lena Dunham, cinematography Jody Lee Lipes, music Teddy Blanks, Transmission DVD, www.transmissionfilms.com.au

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 22

© Neph Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

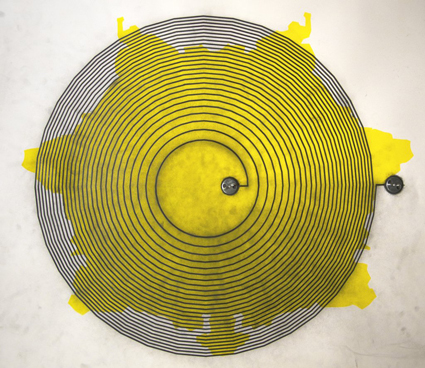

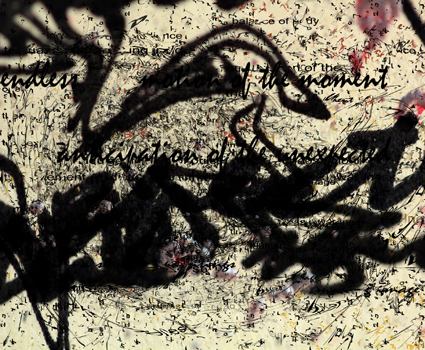

AU Smart Phone installation

The Future. Every proto-modern millennium has kick-started its identity with a wild rash of dreams. Yet many people seem unattuned to the cruel trick being played: when you get to the Future, it becomes the Present. And the Present is that awful place from which so many people wish to escape.

When Steven Spielberg was in pre-production on Minority Report (2002), he convened a small group of unnamed ‘futurologists’ for three days in a Californian chain hotel. This “imagine tank” workshopped how technologies, interfaces and man-machine production/consumption would appear in the Year 2054. The most prescient moment in the film occurs when Tom Cruise is being chased through a hi-tech shopping mall. The large vertical screens in the Gap store show video footage of store personnel who greet Tom by name as he stalks through. They even make suggestions as to what he might like from their new range. Like all futurologist visions, that scene already existed in the minds of companies like Gap. And like all futuristic visions, it is terraformed in the Present.

When the large ShinQ Mall opened in Shibuya in 2012, it featured a large proportion of Digital Signage: custom designed/installed video screens projecting networked data, often synchronised with multiple displays. The Natural Market chain store in the lower basement food hall has interactive digital signage featuring a live feed of the person standing in front of it (filmed by a tiny camera to the left). Cartoon thought bubbles track the movement of the subject’s head, expressing phrases like “I’m going to cook Chilli Shrimp tonight!” The image of the subject is then replaced by a recipe and ingredients (purchasable from Natural Market).

Gimmicky as it is, the perverse futurism of this digital signage lies in its facetious projection of ‘what’s inside the consumer’s mind.’ Futurologists since the 1960s have predicted that marketing/advertising communicating signage (à la Minority Report) will read minds and tabulate desires. The Present à la Natural Market jacks that notion and simply fabricates the image of your mind being read, and predicts what your flaneur mind probably would have said regardless. The Natural Market phrase not only takes place in the anacoustic realm where thoughts seem to appear ‘spoken’ in one’s head, it also results from you reading a response which triggers an anechoic echo of a voiced thought in your head which you never actually thought. This confusion of Self, thought and voice causes a mild-meltdown which is assuaged by ‘identifying’ with those triggers as if it is a pleasurable narcissistic moment.

AU Smart Phone installation

Adults and children alike in today’s Hyper-Narcissistic era will accept anything if a photo of their own face is attached to it. The winner of the 2013 Digital Signage Awards in Japan this past April was a walk-through installation at the Shinjuku JR outdoor plaza, produced to market AU network smart phones (AU Sumauro Pasu, 2013). A series of booths employed self-projection of recorded visitors’ faces, but here digitally attached to animated figures of folksy woodland creatures prancing and dancing around a kids’ book wonderland. (Think Gondry-artifice meets Shibuya-kawaii scored by a shambling band from Portland playing xylophones.)

The visitor’s face is first scanned, then rendered into a fake 3D mask, and finally positioned onto the ‘face holder’ of the main animation. Integrated into the rolling animation, the visitor’s face moves and tilts in congruence with the animated figure’s shifting axis. The result of this data processing is to feed ‘your face’ into the multiple synchronised screens of woodland creatures frolicking in unison. Moreover, animated black holes are affixed to your mouth to portray you singing the AU Smart Pass jingle. In a truly futuristic twist on existentialism, your face has become voiceless in proportion to how your voice has become faceless. For it is not ‘your face’ onscreen: it’s the data of your face projecting a mirror effect of what your face would do if it were not you but the ‘you’ desired by the company instigating this audiovisual illusion.

Yet the Japanese context here gives rise to another possibility. Masks in Japan do not simply signify the withholding or concealing of expression. Rather, the mask is an epidermal barrier between thought and word, sense and language. It is a vessel for containing whatever is transferred into it purely by donning the mask. European linguistics do not operate this way due to a variety of complex constructionist and deconstructionist frameworks which articulate determining relations between the Self and language. Looking, reading and listening to your own face in something like the AU Smart Phone installation—cannily replicating a trickster hall of mirrors—facilitates not identification with the Self, but acknowledgement of the you that isn’t there, wherein you experience the image of your own voice.

This year in Akihabara, the Animate store shifted this effect into the 3rd person. An anime-style young woman dressed in casual attire stands in a life-size vertical screen display. Motion sensors program her to call out to you as you pass by. If you stop, she engages in direct questions. A microphone is prominently displayed, inviting you to talk back and ask questions. Essentially, this animated program is a sutoa-nabi (store navigation) display: an info port where you find out what shops are on which levels, and what goods each store has in which sections, plus the animated girl is based on actual young women posted in info booths in large department stores.

Despite her welcoming appearance, this digital display is built upon a database of polite refusals. For example, asking her age will get the definitive Japanese response: “Yes, that’s a hard question to answer,” delivered with a nod. Even though a visitor uses their voice, it is never heard. Instead, it is analysed through speech recognition software and channelled into a pre-ordained communicative stream for eliciting a pre-programmed response. Within the Japanese cultural context, this type of programming is not an awfully inhuman future (feared by Western futurologists), but an idealisation of how rigidly the human can conform to the strictures of social protocol. Again, it’s a virtual imagining of how your voice is rendered as pure image, despite whatever linguistic tools are presumed to be used.

But if Japan is a realm where the Self is razed into a selfless mirage of identity, forever interweaving between masks, it is also maybe the only place where such destructive personification can be celebrated. For Halloween this year, Bacardi Rum in Japan brainstormed some ideas and dryly summated: “We focused on the tendency for drinkers to get louder as they consume alcohol.” Now if this were the Spielbergian futurologists of Minority Report, the outcomes would have been as banal a ‘vision’ as that film’s Gap store digital signage.

But Bacardi Japan came up with Bacardi Scream Halloween (2013): a sexy woman dressed as a witch has her tarty costume modified so that strips of her thighs, waist and breasts are covered with a special fabric which ‘becomes transparent’ to reveal her flesh, as if one is looking through retro-50s X-Ray Spex. But to get her attire to ‘become transparent,’ one must scream into a microphone at the end of her broom handle, which tabulates the decibel level of the scream and accordingly rates the value from low (her thighs) to mid (her waist) to high (her breasts).

Here, the voice is rendered image—but the cynical operations are strikingly apparent: your voice technologically activates the manifestation of a desired image. In a perverse rebuttal of the AU ‘community’ campaign, the Bacardi campaign culminated in a live event at Club Nicofarre in Tokyo (famous for its huge video walls on three sides of the club). All the screams gathered by the roving sexy witch were encoded, then pitch-assigned into a sampling bank which was then played by a wild hard rock guitarist brandishing a MIDI-guitar (yes!) who did Steve Vai style solos which unleashed the sound-bite screams of the hordes who fed their voices into this data-tabulating apparatus. Plus, a camera had also recorded each scream, and when the guitar solo was performed, each scream’s audio-sample also triggered flashes of the participant’s face screeching into the camera, now played across screens in the club.

Collectively, these examples of recent Digital Signage advertising in Japan reveal how readily people will surrender their Self (face and/or voice) into a data-pool which will mirror and/or echo an image entirely devoid of that Self which served as input. US-dominant web.02-style communalisation (crowd-funding, wiki-teaming, user-voting, choice-tracking etc) continues to paint its outcomes as fantastical apparitions of the Future inhabiting the Present—just as futurologists dream things will be. For those not impressed by such Spielbergian dreams, all those crowds amount to hordes simply in love with the image of their own voice.

–

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 23

© Philip Brophy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

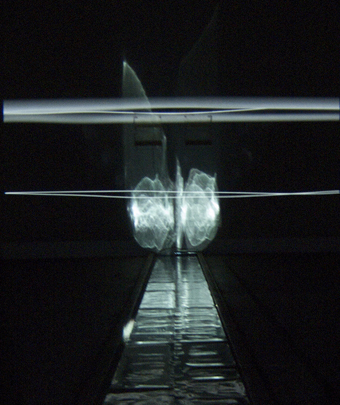

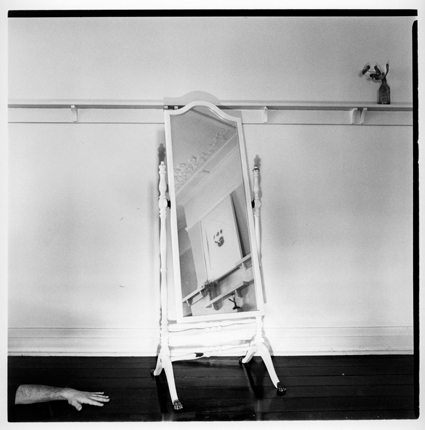

Jacqui Shelton, Silt/Suspended Load (2013), courtesy the artist

Wandering into the darkened main gallery of Gertrude Contemporary on the first afternoon of the Experimental Congress, the visitor was greeted by two prominently placed video loops selected by the curators of Melbourne’s Screen Space. In Jacqui Shelton’s Silt/Suspended Load (2013), Shelton is filmed from a fixed camera angle as she dangles from a ladder, swinging gently back and forth. In Walk III (2010) the camera tracks alongside maker Anna Fuata as she strolls past weatherboard bungalows in what appear to be Melbourne’s northern suburbs: the uncanny quality of the piece stems from the fact that it consists of reverse-motion footage of Fuata walking backwards, though it takes a while for the penny to drop.

Each work functioned as a geometric cityscape as well as a document of a performance: viewed full-length from an unchanging distance, the artist-stars resembled video-game protagonists, focused on nothing beyond an immediate, seemingly pointless task. At the outset of a three-day event examining the past, present and potential future of Australian experimental film and video, it seemed worth pondering the allegorical implications. Were we permanently suspended, trapped in an endless cycle? What could it mean to move backwards and forward at once?

Convened by Danni Zuvela and Joel Stern of the (originally) Brisbane-based OtherFilm group, the Congress was itself conceived along an avowedly circular premise, as an exploration of “the concept of collectivity:” in other words, bringing people together to discuss what the point of bringing them together could be. Evening screenings and presentations were preceded each afternoon by informal roundtable discussions, open to the public but attended mainly by curators and artists at the rate of about a dozen per day. Historical background was supplied by group elders Dirk de Bruyn and Richard Tuohy, spinning tales from those far-off days of the mid-to-late-1990s, when the Melbourne Super-8 Film Group flourished at the Erwin Rado theatre in Fitzroy and Sunday night screenings of avant-garde classics were held at Cafe Bohemio just around the corner.

Truth be told, I can remember some of this stuff myself, strange as it seems to have lived through an era when experimental moviemakers could function without significant commercial ambition in an analog world, rather than as entrepreneurial digitally-savvy ‘creatives.’ The Super-8 Group recurred as a reference point throughout the Congress, with De Bruyn devoting half a presentation to the best lines salvaged from their newsletter (“Be suspicious of men with cameras and record collections instead of girlfriends,” from the late Vikki Riley, remains the money quote).

It would be unwise to go too far in romanticising the group, given the hit-and-miss offerings at any given open screening, not to mention a management style which (by all accounts) was exactly what you’d expect from an organisation run on a shoestring by cranky artists. Yet it did provide a space where hobbyists, purists, go-getters and try-hards of all stripes could rub shoulders and exchange ideas. This was a milieu where even narrative filmmakers such as Bill Mousoulis and Mark La Rosa were able to stay in touch with an experimental culture; likewise, it’s uncertain if Tony Woods’ sophisticated mingling of documentary and abstract modes would have found an equally receptive audience elsewhere.

Nowadays such pluralism feels all but unimaginable, except perhaps online. The somewhat passive-aggressive opening statement of the Congress took up this theme, citing Freud’s notion of the “narcissism of minor differences” in relation to organisations competing for slices of the funding pie. Now that most so-called film is entirely digital, the question of medium specificity is moot—though a few diehards such as Tuohy and his associates at the Artist Film Workshop cling to the old avant-garde traditions, like monks still toiling at illuminated manuscripts in the age of printing. In the meantime, many video artists remain averse as ever to anything that smacks of cinematic craft, though most would presumably acknowledge in principle that no action can be recorded in a ‘neutral’ way.

Too bad the discussions never got down to the nitty-gritty of exploring what artists fixated on the material qualities of celluloid could learn from those concerned primarily with performance and duration, and vice versa. But then, for every testament to the value of co-operation the Congress offered a reminder of the innately (and valuably) antisocial side of the avant-garde—in De Bruyn’s preoccupation with paralysis and trauma, in Tuohy’s abrasive flicker film Dot Matrix (2013) and perhaps most viscerally in the work of Andrew Harper, whose Piss (light) (2007) was the upshot of submerging a reel of Super-8 film for a year in the titular bodily fluid. This was shown in a video copy, the original being too fragile and precious to risk; Harper’s initial, unrealised plan was to project it onto a ‘screen’ consisting of his body, where the material basis of the work originated. This was another kind of closed loop, again echoing the solipsism of the Congress more generally; explicitly political issues were hardly broached, apart from some forlorn talk about Occupy-style takeovers of public space.

Still, discussion did give rise to some modest, practical suggestions about how a sense of community might be maintained: through an email list, for example, or a successor to the film co-ops of the past. Another technique of circuit-breaking was suggested by reports of curatorial projects aimed at bringing experimental film and video to a wider audience, such as De Bruyn’s Outside the Outside screening series in Dandenong, or the annual shows which Jim Knox has mounted in recent years at the Meredith Music Festival. Knox’s presentation to the Congress included extracts from numerous oddities in his collection, ranging from a 1950s Disney cartoon about life on Mars to an extraordinary found-footage montage by Soviet director Elem Klimov, satirising the decadence of the West. As ever, his admirable approach is less about irony than about getting us to recognise the cockeyed artistry in work far outside any official canon—demonstrating, in passing, that history can always be written anew.

Experimental Congress, convenors Danni Zuvela, Joel Stern, Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne, 30 Oct–2 Nov

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 25

© Jake Wilson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Deborah Mailman, Marcia Langton, The Darkside

photo Tony Mott

Deborah Mailman, Marcia Langton, The Darkside

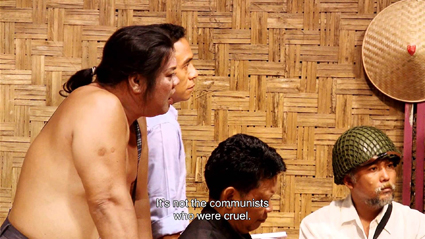

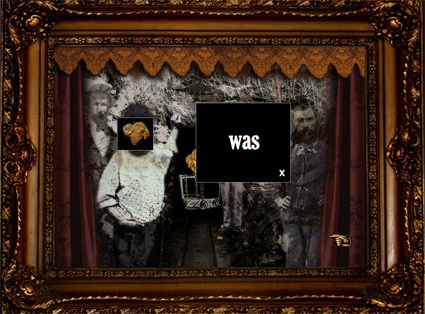

Drawing upon primal fears of darkness and the mysteries of death, the ghost story is perhaps the most relatable of tales. With this feature-length addition to a venerable ghost anthology tradition which encompasses collections of stories from different cultures, eras and individual writers, Samson and Delilah (2009) writer-director Warwick Thornton seeks to explore an Indigenous experience of the ‘other side.’

After calling via traditional and social media channels for first-hand accounts of ghostly encounters, Thornton and producer Kath Shelper narrowed an initial 150-odd submissions down to a dozen. Using Thornton’s interviews with these 12 storytellers as core material for the screenplay, the resulting film is part-genre, part-oral history project. It is full of a promise that doesn’t quite materialise.

Except in a couple of cases where the storyteller doesn’t appear onscreen, each story is presented essentially in monologue by an Australian actor, with Bryan Brown, Deborah Mailman, Claudia Karvan, Aaron Pedersen, Jack Charles and Sacha Horler among the prominent names featured. Thornton’s preferred approach is to maintain a largely static shot of the teller in his/her environment—an environment that sometimes reflects the narrative (river and coastal stories are told by Brown and Horler near water; Shari Sebbens’ account of a family vigil for a dying infant is told in a hospital). In some instances, however, more lateral or abstract images are superimposed over the teller’s voice, most notably during Sharon Cole’s eerie roadside tale, accompanied by artist Ben Quilty working close-up on one of his characteristic impasto landscapes. Ultimately, the painting resolves at a distance into an image which resonates with the story’s conclusion. It’s a texturally interesting approach, though the footage tends to compete with the words.

It’s no coincidence that the more concise stories, as well as those whose visuals accentuate rather than nullify the verbal content, are among the more engaging in the collection. Filmmaker Romaine Moreton speaks of a troubled residency at the National Film and Sound Archive, formerly the Australian Institute of Anatomy, over a pastiche of foreboding interiors, historical ethnographic footage and the piercing light of a film projector—images which lend a clinically cruel edge to her account of the unsettled dead. Some narrators command more attention than others, with skilled raconteur Jack Charles at the fore here.

The Darkside’s main problem is verbosity. Thornton’s commitment to exactly replicating these interviews, intrinsically interesting as they are, is at odds with the overwhelmingly visual nature of cinema. As tales meander and fall into repetition, the viewer’s attention wanders. The director’s recent forays into video installation with Stranded, 2011 (commissioned by the Adelaide Film Festival; RT102) and Mother Courage, 2012 (commissioned for Documenta13; RT113) seem to have influenced The Darkside’s deliberate pace and use of imperceptibly changing imagery. It’s an approach that’s more suited to the fluid dynamic of a gallery than the captive situation of the movie theatre, where attention needs to be seized and maintained. Thornton might have been trying to avoid horror movie clichés, but attention to the way the best genre cinema manages to grip its audience viscerally would have given these stories a far greater chance to shine.

The Darkside, director, cinematographer Warwick Thornton, editor Roland Gallois, sound designer Liam Egan, producer Kath Shelper; Australian distributor Transmission Films

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 26

© Katerina Sakkas; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Despite burgeoning interdisciplinarity and crossovers, the line between art and the creative industries over recent decades remains firmly etched in the cultural psyche. In our Art, Wellness & Death feature in RealTime 117, we profiled artists Efterpi Soropos and George Poonkhin Khut who are developing commercial applications of their creations to aid the dying and those in pain, without surrendering their sense of being artists. I have friends who would be labelled ‘creatives’ in the commercial world whose inventiveness surpasses that of many an artist but who bemoan their lack of artistic freedom given the narrow ambit of commercial design and other practices in Australia.

George Hedon, an art director for a Melbourne advertising agency, co-founded Pause Fest with Filip Nakic four years ago with a passion to “create a collective digital community,” bringing together creatives who might normally not mingle, let alone collaborate, from a wide range of industries engaged with digital technologies: “advertising, digital design, animation, production and post-production, as well as incubators and start-up communities.” I recently spoke with Hedon about the festival and its ambitions.

Hedon, who had no experience of running a festival, has grown the event by encouraging the generosity of speakers, pro bono support, in-kind donors and volunteers (some 30-60 per festival), such is the enthusiasm for the event. The response from the field has been strong, the scale of the festival grows and the City of Melbourne has proved financial support for the 2014 Pause Fest.

Pause Fest takes creatives outside their usual parameters, offering pause: time-out to meet, think and potentially collaborate. This year’s festival theme is “connections,” between individuals and industries. Hedon believes that the event has generated “a collective digital community” via “a non-profit event in which any income is put into the festival’s future.”

In our discussion there’s occasional telling slippage in terminology. When I ask Hedon how important it is for creatives to escape the boundaries of their professions, he answers, “It’s the most important thing: to be able to express yourself, in your artform, to explore your ideas and then apply yourself to a commercial world.” Do all the outcomes have to be commercial? “Everything ends up being commercial,” he replies. But it’s individual creativity and identity that counts: “You have to have your own signature before you go into the commercial.” Which is where Pause Fest offers succour. However, Hedon admits, “we’re sitting on a fence of what is commercial and what is art. We’re really pushing [the] art and technology [connection].”

It’s not surprising then that Hedon is particularly pleased with the festival’s interactive installations program. Ten works were short-listed and two chosen for realisation.

Three of the works are Australian, one is Polish. The brief was to create installations that would “engage a wide audience: adults, kids, families, the elderly.”

A key part of the Pause Fest program from inception is animation: the first encouraged collaborations between animators and sound designers around the world. Overseas makers, who mostly work in post-production and other areas of commercial production, are grateful for access to Pause Fest’s animation program, although Australians, says Hedon, are less eager, but are catching up. A very broad theme is set for the animators to apply to an otherwise “blank canvas.” Last year the theme was “the future,” which resulted in “some very dark work. It’s a happy theme this year.” The works will be screened at ACMI, on Federation Square’s big screen and online.

Pause Fest has an extensive program of talks and forums to which has been added for the first time an intriguingly titled event, PanicRoom. Hedon explains it’s the creation of PostPanic, a post-production company in Amsterdam founded by its Creative Director Mischa Rozema, a keynote speaker at this year’s festival. PanicRoom gatherings, explains Hedon, “are not about making speeches or talking about the work. They are interested in everything else: what creative people like, what their influences are, their experiences, their favourite music—who they are and what makes them tick.” PanicRoom will feature Australian creatives, revealing dimensions that feed their creativity in a four-day Pause Fest that will buy them some liberating time-out.

2014 Pause Fest, ACMI and Federation Square, Melbourne, 13-16 Feb, www.pausefest.com.au

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 26

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Joanne Mott, Grounded, 2013, native grasses, sedges and rushes, Palimpsest

photo John Power

Joanne Mott, Grounded, 2013, native grasses, sedges and rushes, Palimpsest

“Palimpsest means a parchment that has been partly erased and re-inscribed. It evokes the marks made by human settlement on the land, the passage of time, presence and absence and the web of inter-dependence uniting the natural and the cultural, the material and the immaterial.”

www.artsmildura.com.au/Palimpsest

The “Biennale of the Bush,” as Palimpsest is sometimes known, is huge, both in terms of the number of artists participating and the sheer geographic scale of the event. Since its inception in 1998, the environment has been a recurring theme in Palimpsest. Outdoor works featured prominently this year, some hearkening back to the Mildura Sculpture Triennials of the 1970s—among the first events in Australia to move out of the gallery and situate artworks in the natural environment. This link was particularly notable in Joanne Mott’s living installation, Grounded, located in the very same park (a reclaimed rubbish dump) that housed the outdoor artworks of the Sculpture Triennials.

Mott’s creation has sustainability at its core. It uses living, Australian native, anti-erosion grasses planted to spell out GROUNDED, reflecting various interpretations of the word, including the very soil in which the grasses are planted and the concept of being psychologically earthed. This work is a continuation of Mott’s practice of planting and her conceptual interest in what she describes as the “heterogeneity of ‘nature’ and ‘culture’,” which are united in her artworks (www.joannemott.com). In Grounded, the health of river systems is reflected in the proximity of the artwork to the river and her use of soil erosion grasses that prevent riverbanks from being washed away. Clearly hand-planted, Grounded emphasises human presence, encouraging consideration of the efforts people make to repairing the environment.

Danielle Hobbs, 7000 eucalypts, 2013, mixed media installation, Palimpsest

photos Kristian Häggblom

Danielle Hobbs, 7000 eucalypts, 2013, mixed media installation, Palimpsest

Danielle Hobbs’ 7,000 Eucalypts comprised a gallery-based sculpture and a large site-specific artwork, drawing on the symbolism of a famous work by German artist Joseph Beuys: 7,000 Oaks. Completed by Beuys and the townsfolk of Kassel for Documenta 8 in 1987, it bore a message that related to both environmental remediation and urban renewal. This resonated with Hobbs, who reworked Beuys’ idea into an artwork that also had personal resonances for her. On a property managed by her father, the artist reframes a forest of hundreds of Australian gums from plantation trees into both an artwork and an environmental statement. Each tree was spray-painted with a pink dot, like those that councils use to indicate a tree destined for removal. The trees in 7,000 Eucalypts reflect new thinking about sustainable logging, but are also, says Hobbs, a reminder of the thousands of old-growth forests being cut down every day (Artist Talk, 5 October).

Hobbs has maintained a sense of environmental responsibility since her youth and admits to being a vocal critic on the subject, even within her own family. Thus, her father’s movement into sustainable logging makes the work personal. From the perspective of an observer kept behind safety fences, I found the number of trees marked for felling moving—representing a metaphorical and very real barrier between humans and the environment given the ongoing demand for wood-based products. The number of forests that are logged is alarming though there was some relief in knowing that these trees were not old growth.

Hobbs’ gallery-based work was featured in the ADFA building, recently refurbished as an art gallery, having formally housed the Australian Dried Fruits Association and fallen into disrepair. Hobbs describes her work as “art as an ecological intervention,” drawing on environmentalist themes and presenting them as art. The sculpture in ADFA draws on the same imagery as in the plantation, but we are instead presented with sawn logs. Stretching between plantation and gallery, 7000 Eucalypts offered passive yet powerful imagery, linking iconic Australian trees, and therefore the greater Australian environment, with the global one by referencing Beuys’ 7,000 Oaks. A sense of the presence and absence in trees growing and logged, was consistent with the Palimpsest theme.

Also using the outdoors and gallery space to engage with the environment, David Burrows drew on the landscape of Mildura’s Lake Ranfurly, an artificial stormwater basin covering almost 200 hectares. My first impression of the ‘lake’ was of a large open span of sand, devoid of water, invoking concerns about water security in Australia. In this ‘lake,’ Burrows presented Mirage Project ….[salt], a reinterpretation of his Mirage Project ….[iceberg] presented in 2012 in Melbourne’s Federation Square. This project utilises stereoscopic 3D photographs of icebergs taken by Burrows in Antarctica and seen, on the lake, through mounted binocular slide viewers. These works were carefully positioned so that the viewer could see the icebergs from the same positions that the original photographs were taken. These images of beautiful, naturally formed ice sculptures contrasted sharply with the arid lake. As you see the three-dimensional detail of the icebergs, your body feels the dry heat and baked sand, generating a sense of the very real potential of global warming to transform one landscape into the other. Burrows’ companion work, Crepuscule was featured at Mildura’s Wallflower Photomedia Gallery presenting beautiful photographs of the slowly changing effects of light on Lake Ranfurly.

Juan Ford’s Lord of the Canopy at the Mildura Arts Centre, embodied the nocturnal ambience of nature in a darkened gallery lit with spotlights casting ominous shadows on the walls. A large tree on the gallery floor comprised several segments, visibly bolted together into what Ford describes as a ‘frankentree’ (Artist Talk, 6 October). A highly polished possum ring (sheet-metal designed to prevent animals from climbing trees) was positioned on the trunk to reflect a large, circular painting of the warped image of a possum on the gallery wall, establishing a dialogue between the natural denizens of the Australian night and the human hand on the environment. Walking through Lord of the Canopy, I felt the need for quiet and slow movement as one might when encountering a possum at night in your backyard. Yet that feeling of wonder was overshadowed by the ‘wrongness’ of this bolted-together, artificial tree and the denial of the possums’ natural home represented by the ring.

These works, just a few of the many created by the 49 artists in this year’s Palimpsest, demonstrated not only a developing subgenre of Australian art concerned with the environment, but also a wider consciousness of the natural environment and a gradual inscription and re-inscription of the environment. While I’ve focused on works with direct environmental concerns, other artists created works with subtler tones of environmentalism and a diverse array of other themes including surveillance, mental health, blended cultures and the changing face of Mildura. Palimpsest is a powerful event reflecting many current concerns through the lens of contemporary art.

Arts Mildura, Mildura Palimpsest Biennale #9, curator Helen Vivian, assistants Geoffrey Brown, Rachel Kendrigan, Rohan Morris, various venues in and around Mildura, 4-7 Oct, www.artsmildura.com.au/palimpsest/

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 28

© Jane Wildy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alana Everett, Lauren Langlois, Rennie McDougall, Lily Paskas, Lee Serle, A Small Prometheus

photo Jodie Hutchinson

Alana Everett, Lauren Langlois, Rennie McDougall, Lily Paskas, Lee Serle, A Small Prometheus

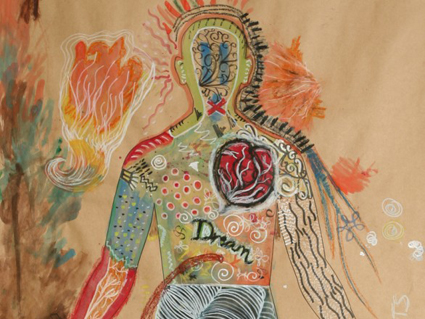

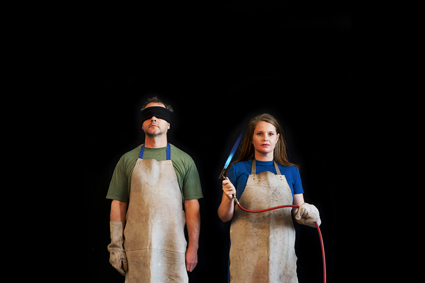

The beginnings of a dance work, or any project for that matter, may be happenstance. A match is struck: the spark of an idea flashes, catches, gently glimmers and grows. Eighteen months later, five dark figures cluster around three metal sculptures, methodically lighting a circle of candles. The heat created by their combined candlepower causes a circular propeller to spin, gently pinging and sounding as it revolves. This is an altar to the power and beauty of fire, a ritualistic beginning, which transforms heat into movement.

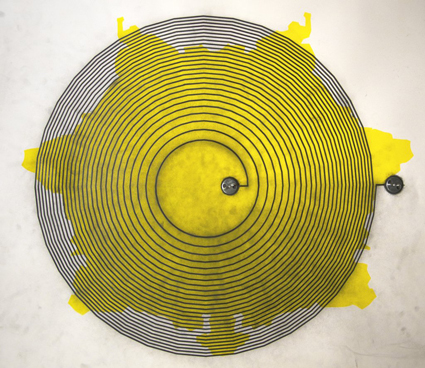

Kinaesthetically, much the same happens. Bodies roll, push, pull, crawl, arch and twist into sitting and standing. Five dancers line up along a diagonal; runners at the starting line. There is a kind of pause, an in-breath before the dancing begins. The work is poised before its own future. We know that A Small Prometheus is about fire but, given this is not a narrative, how does the idea of fire meld into movement? Stephanie Lake’s treatment of her topic merges with the musical input of her collaborative partner, Robin Fox. Billed as a joint creative venture, we find the music playing an equal, sometimes dominant, role in the work. Mostly this enhances the quality of the dancing but sometimes eclipses it. While all dance to music needs to determine its relation to the music, the nature of this collaboration raised the status of the sound. If the music takes the lead, the challenge is to take up its stimulus without surrendering to it, to make the sum greater than its parts.

A Small Prometheus consists of a series of responses to its theme. It offers a kinaesthetic poetics of fire played out in the body. For example, impulses work their way through the dancers’ bodies which jerk at speed. Each body has its own way of enacting these qualities. Lily Paskas rips through space without pause for thought. Sometimes the dancers are dancers, forming duets, circles, lines, hoisting bodies, lifting legs. Other times, their bodies are a staging ground for actions that reflect ideas of fire, heat, light or convection.

As this dance is performed, bushfires rage in the Blue Mountains, destroying hearth and home with a fearsome intensity. The dancers stage a form of collapse in their bodies. There is less sense of danger here however, for the group hovers, ready to catch them. Rennie McDougal performs an interesting solo with elements of collapse and support within his own body rather than in partnership with the group.

Returning to ritual, four dancers sit in front of large ashtrays, striking matches in time to the sound. These simple relations between light and sound are mesmerising to watch, an aesthetic form of child’s play.

At some point well into the piece, the choreography really took off, in terms of flow, intensity and energy. It would have been wonderful to see the entire piece operate at this level. This is probably a question of time and resources, to be able to dwell with the choreography, edit, rework and polish. Another iteration of this piece-—a phoenix perhaps—might consider the coherence of its parts, the relation between its sections, and to the theme as a whole, moving beyond an episodic feel to some other sense of structure or interrelationship between the various thematic moments.

A Small Prometheus, creators Stephanie Lake and Robin Fox, choreographer Stephanie Lake, composer, sculpture designer Robin Fox, performers Alana Everett, Lauren Langlois, Rennie McDougall, Lily Paskas, Lee Serle; Arts House, Melbourne, 15-20 October

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 31

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Teenage Riot, Ontroerend Goed

photo Sarah Walker

Teenage Riot, Ontroerend Goed

Cinema theory has a wonderful term that doesn’t quite have an equivalent in the discourse around theatre: exploitation. In both industry and critical parlance, the exploitation film has long been that which panders to a particular (often prurient) interest, ‘exploiting’ an exotic or vaguely taboo subject and equally ‘exploiting’ a niche audience attracted to such fare. These are the B-movies of suburban drive-ins, grindhouses and midnight marathons. Perhaps it says something of the overwhelming gentrification of theatre in the 20th century that equivalent alternative avenues have mostly failed to find popular appeal.

Ontroerend Goed, Teenage Riot

While viewing Ontroerend Goed’s Teenage Riot my mind kept returning to the subgenre of teensploitation. It’s a rich vein in film, canvasing everything from the saccharine beach party movies of the 60s to the sensational slashers of the 80s and the more respectable output of director John Hughes during the same period. Originally intended with no more noble goal than to rake in the pocket money of high schoolers, the teen film over time became a way for its typical consumer to develop a sophisticated and critical engagement, assessing the truth and artifice of the depictions on screen and defining an identity both through and against them.

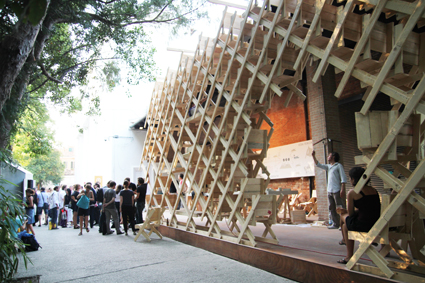

Teenage Riot could be understood as a live comment on all of this. It’s the second part of Ontroerend Goed’s trilogy of works performed entirely by teens, and it explicitly concerns itself with the spectatorship: for much of its running time the large staff of players are hidden inside a wooden box, manipulating handheld video cameras to reveal projected fragments of what’s going on inside. That the audience is therefore cast in the position of voyeur (another nod to film theory) isn’t just implicit. Performers offer teasing glimpses of bared flesh before laughing defiantly down the camera lens, make out with one another and offer instructional sermons on fingering, bully and brutalise and shrug it all off with irony or indifference.

The work could be a challenging, even confronting gesture of inter-generational defiance, and a knowing rebuke to elders who assume teens are incapable of reflecting upon their lot with any critical distance. But here’s why I really began pondering teensploitation: the work is billed as written and directed not by its performers but by Ontroerend Goed artistic director Alexander Devriendt and dramaturg Joeri Smet, neither of whom is close to his teens. I have no idea of the process of development the work underwent, but when a pair of adults append their names as the primary creators of a work concerned with teenage excess and libidinal overflow, which furthermore positions its audience as leering creeps—well, where are Devriendt and Smet in that equation? Teenage Riot leaves everyone looking a little bit dirty, except its notably absent makers.

Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert, All That is Wrong, Ontroerend Goed

photo Elies Van Renterghem

Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert, All That is Wrong, Ontroerend Goed

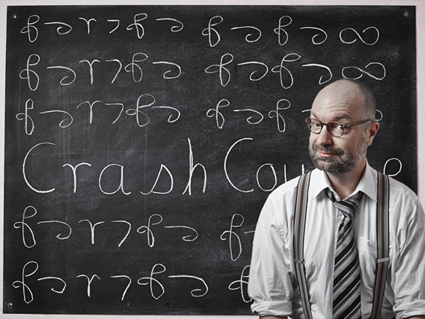

Ontroerend Goed, All That is Wrong

The third in Ontroerend Goed’s teen trilogy, All That Is Wrong, is a refreshing curative. Performer Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert is also the work’s writer, in more than one sense: the piece consists of Ryckewaert scrawling countless words in chalk on an expanse of blackboard filling the floor of the playing space. The 18-year-old is joined by another youth, Zach Hatch, who films the text as it is written (and which is then projected against a backdrop) as well as operating sound cues. Occasionally the two will speak, but are silent for most of the work’s duration.

Ryckewaert writes the word ‘I’ and begins to add modifiers – ‘18’, ‘Belgian’, ‘introvert’ – which quickly spiral out to encompass a less certain and more connected cross-hatching of identity: corners of the space become crowded with personal fears or global horrors, while earlier sections are revisited and revised. The overall effect is cumulative: we are left with the unmistakeable sense of someone who both thinks and cares a great deal about the world into which she is graduating, and of a work that trusts its maker enough to let her do the talking. Or, at least, writing.

In Spite of Myself, Nicola Gunn

photo Sarah Walker

In Spite of Myself, Nicola Gunn

Nicola Gunn, In Spite of Myself

Melbourne performance maker Nicola Gunn has for some years exploited the most interesting of subjects: herself. Or, at least, an amorphous figure known as ‘Nicola Gunn,’ though one could keep adding more and more quote marks around the name as the meta-theatrical frames around her investigation have continued to multiply. In Spite of Myself is her most accomplished (not to mention hilarious) experiment yet. It’s ostensibly a retrospective exhibition of works by Nicola Gunn entitled Exercises in Hopelessness—Nicola Gunn (1979-present), with a bonus lecture by Susan Becker, international curator at Arts Centre Melbourne. Becker is, of course, Gunn, but Gunn is not entirely Becker, just as ‘Gunn’ is not Gunn, and the way the performer flips between different masks rapidly begins to resemble the cups and ball trickery of a fleet-fingered street magician.

Where Gunn’s ongoing project is most interesting is in the way it amplifies the utter artificiality of theatre, and an extreme form of self-reflexivity that is consistently ahead of its audience, while remaining deeply autobiographical and resoundingly true. Gunn makes art about making art, but rather than descending into navel-gazing she dredges up the very intimate pains and absurdities of that experience. She exploits a trio of older women by giving them the task of fashioning hundreds of tiny clay figurines, which she promptly stomps all over. She rails against the recycling practices of the Arts Centre that is presenting her work, even though that work itself will end up as a very real pile of garbage by the show’s end.

And underlying the futile artistic acts in which Gunn indulges is the worry that all art is quite useless, that she is yelling into a void. Where many peers stall at precisely that point, Gunn (or ‘Gunn’) somehow forces her audience to join hands and yell with her, creating a shared experience she describes as a heterotopia, though naming it seems just one more futile gesture. In Spite of Myself is, indeed, an argument against its own premise, an effacement of Nicola Gunn that produces a sort of ur-identity among her viewers. It’s bloody funny, too.

Emily Milledge, Room of Regret, The Rabble

photo David Paterson

Emily Milledge, Room of Regret, The Rabble

The Rabble, Room of Regret

That “all art is quite useless” is the contradictory provocation that prefaces Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray, the latest text to be mercilessly ravaged by Melbourne outfit The Rabble. As with all of the company’s work, a familiarity with its source(s) offers no magic key to unlocking its secrets, and Room of Regret is in some respects its most inward, mysterious production so far.

The performance occurs within a maze-like installation in which audiences are split up and seated in separate rooms. Performers are often invisible to a good portion of that audience, then, or mediated via screen and projection. The text is similarly splintered, with short portions of Wilde’s words carved from their context and repeated over long durations, usually in a heightened and histrionic manner.

The visual realisation of the work is decadent, lush, almost overpoweringly so, drawing in influences from the Baroque and Victorian to 70s glam and contemporary performance art. The design, too, is both disorienting and appropriate—in separating audiences and their gazes, we are no longer the crowd but become keenly aware of our disconnectedness in a shared experience. Excess and anomie thus shift from themes in a novel to very palpable sensations in this work, and once again where The Rabble exceed most others is in producing this visceral, rather than literal, conjuring of a written text’s essence. It’s uneasy, incomplete, even hard to like, but almost impossible not to admire.

Melbourne International Arts Festival: Ontroerend Goed, Teenage Riot, director Alexander Devriendt, writers Joeri Smet, Alexander Devriendt, Fairfax Studio, 15-18 Oct; Ontroerend Goed, All That Is Wrong, writer Anna Jakoba Ryckewaert, director Alexander Devriendt, Fairfax Studio, 19-20 Oct; Sans Hotel, In Spite of Myself, creators Nicola Gunn, Gwen Holmberg-Gilchrist, Pier Carthew, Michael Fikaris, performers Nicola Gunn, Maureen Hartley, Brenda Palmer, Annabel Warmington, Fairfax Studio, 9-13 Oct; The Rabble, Room of Regret, creators Emma Valente, Kate Davis, director Emma Valente, design Kate Davis, performers Pier Carthew, David Harrison, Alex McQueen, Emily Milledge, Mary Helen Sassman. Theatre Works, St Kilda, Melbourne, 21 Oct-3 Nov

RealTime issue #118 Dec-Jan 2013 pg. 33

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Life and Times: Episode 1, Nature Theater of Oklahoma, courtesy MIAF

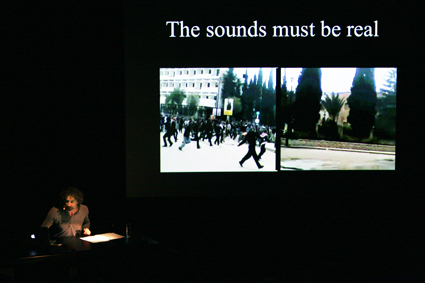

The 10-hour marathon performance of Nature Theater of Oklahoma’s Life and Times: Episodes 1-4 begins with a casual introduction from co-directors Kelly Copper and Pavol Liska. “We are in the business of manipulating time and space,” Liska states, “We want you all to take responsibility for this going well.” Life and Times sets out to transform the entire life story of one person, company member Kristin Worrall, into theatre.

Over 16 hours of recorded phone conversations, Worrall meanders, in painstaking detail, from her earliest memory to age 34. The performance text is a verbatim transcript of these phone calls, preserving every verbal tic, hesitation and redundancy from the original source, every ‘like,’ ‘um’ and ‘ha ha.’ It’s an absurdly quixotic endeavour that could easily have become a stunningly banal vanity project. However, thanks to tight direction, playfully inventive staging and virtuosic performances from the ensemble (Ilan Bachrach, Asli Bulbul, Elisabeth Conner, Gabel Eiben, Daniel Gower, Anne Gridley, Robert M. Johanson, Matthew Korahais, Julie LaMendola, Kristin Worrall), Life and Times is an exhilarating and joyous experience.

In the absence of conventional dramatic content, co-directors Copper and Liska masterfully manipulate the subtle relationship between space, time and stage action. Every glance, gesture and choreographic sequence supports, underscores or cuts across the minor life incident being narrated. Performers move in odd formations while describing everyday experiences, and the punctuation of the original phone call (loops, pauses, self-interruptions) is ingeniously re-purposed to trigger formation changes, exits and re-entries, drink breaks and interval restarts. The performance text is also endearingly self-reflexive about its absurd immensity. Near the two-hour mark, the narrator exclaims: “God, this must be so boring for you. Sorry.”

Life and Times: Episode 1, Nature Theater of Oklahoma, courtesy MIAF