Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

James Turrell, Within without, 2010

lighting installation, concrete and basalt stupa, water, earth, landscaping 800 x 2800 x 2800 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased with support of visitors to the exhibition Masterpieces from Paris

photo John Gollings

James Turrell, Within without, 2010

lighting installation, concrete and basalt stupa, water, earth, landscaping 800 x 2800 x 2800 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased with support of visitors to the exhibition Masterpieces from Paris

james turrell—space within space

“My work is about space and the light that inhabits it. It is about how you confront that space and plumb it with vision. It is about your seeing, like the wordless thought that comes from looking into fire.” So says American artist James Turrell, whose major new Skyspace work, Within without, recently opened at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Commissioned by the NGA as part of its Stage 1 building project, Within without is located in the new Australian Garden on the south side of the building. In order to enter the work, the audience walks down a long, sloping pathway. Once inside, there is a series of spaces: a large square-based pyramid with soft red ochre interior walls, within which there is a stupa made of basalt; inside the stupa is a viewing chamber—a simple domed space, open to the sky. Within without is at its most dramatic and complex at dawn and dusk, marking the transition between night and day. For those who want additional drama, however, there is also a concert on November 27, featuring the music of John Luther Adams, Gavin Bryars, George Crum and Arvo Pärt. James Turrell, Within without (2010), National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; http://nga.gov.au/turrell/

Lyndal Jones, Rehearsing Catastrophe #1: The Ark in Avoca

photo courtesy of the artist

Lyndal Jones, Rehearsing Catastrophe #1: The Ark in Avoca

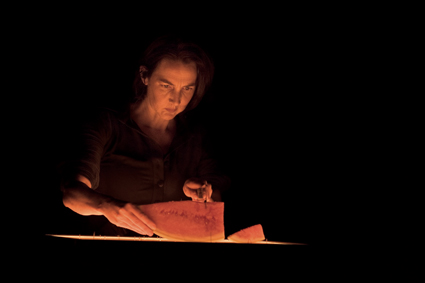

australian ark

Light is also central to Lyndal Jones’ latest creation, Rehearsing Catastrophe #1: The Ark in Avoca, in which a team of artists and locals will work in the twilight to transform Avoca’s Watford House into an ark using large-scale video projections, sound and live animals. The installation, according to Jones, is meant as a “humorous and imaginative preparation for the next flood” and will also produce a video for exhibition on the Big Screen at Federation Square on December 14. Part of the decade-long Avoca Project (see RT83), Rehearsing Catastrophe #1 is Jones’ first performance at Watford House, working with the local community as well as national and international artists, scholars and climate change experts. Rehearsing Catastrophe #1: The Ark in Avoca, Watford House, 16 Dundas Street, Avoca, Victoria; Dec 2-4; www.avocaproject.org

investigation, meditation, immigration

Still in Victoria, the Melbourne Workers Theatre and La Mama present Yet to Ascertain the Nature of the Crime, a production prompted by the recent spate of attacks against Indian students in Melbourne. The show is described as “part-investigation and part-meditation” and seeks to address the attacks within the broader contexts of current economic, education and immigration policies. The show is structured around a compilation of perspectives from Indian students, as well as verbatim material from politicians, doctors and other social commentators. It also features writing by Roanna Gonsalves, Raimondo Cortese, Damien Millar and the company. See also Jake Wilson’s RealTime 100 review of Suri Mohit’s Bollywood feature film Crook on the same subject. Yet to Ascertain the Nature of the Crime, Artshouse, North Melbourne Town Hall, November 24-28; www.lamama.com.au

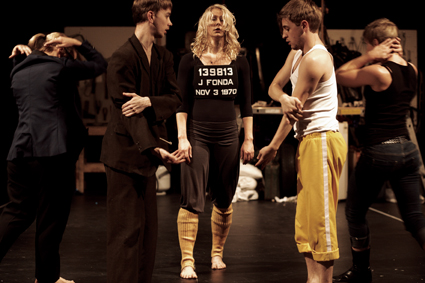

Natalie Rose, Zoe Coombs Marr and Mish Grigor

photo James Brown

Natalie Rose, Zoe Coombs Marr and Mish Grigor

the complete idiot’s guide to the gfc

Regarding verbatim and documentary theatre, Sydney’s version 1.0 are conducting another of their performative investigations—this time into the global financial crisis and the near collapse of capitalism, as part of a double bill with post (Zoe Coombs Marr, Mish Grigor and Natalie Rose) to be staged at Belvoir St Downstairs Theatre. Titled A Distressing Scenario, the production consists of two parts: Everything I Know About the Global Financial Crisis in One Hour, in which post attempt to explain the recession based on as little research as possible; and The Market Is Not Functioning Properly, in which version 1.0’s Jane Phegan and Kym Vercoe examine how phrases such as “toxic debt” and “stimulus package” have entered the vernacular. A Distressing Scenario, a double bill by post and version 1.0, Belvoir St Downstairs Theatre, Nov 25-Dec 19; www.belvoir.com.au

live art in brisbane

One of the websites we here at RealTime keep an eye on is live art list australia, which recently led us to discover the Brisbane-based event exist-ence. In the event’s third incarnation, the Judith Wright Centre Shopfront will be “transformed into a breathing, shaking, writhing space for performance, live and action art” over two nights (website). Local artists, including Dan Koop, Goran Tomic, Jan Baker-Finch, and Melody Woodnutt, will present a range of projects including solo, collaborative and durational works. There will also be international artists streaming live online into the venue and presentations of DVDs, archives and “art-i-facts.” exist-ence: a festival of performance, live and action art, Judith Wright Shopfront, Nov 26-27; www.judithwrightcentre.com

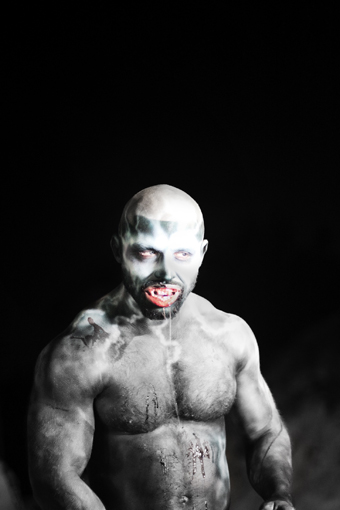

Victoria Hunt, Dancing the Dead, LiveWorks

photo Manuel Vason

Victoria Hunt, Dancing the Dead, LiveWorks

inbetween time

If you’re attending exist-ence or tackled Liveworks at Performance Space recently, then you might consider it training for Bristol’s Inbetween Time Festival, which features 75 events by 130 artists. Several Australians are among their number including Ben Frost, Sarah-Jane Norman, Fiona Winning and Victoria Hunt as well as Back to Back Theatre. They’ll be in the mix with Blast Theory, Tim Etchells, Quarantine, Duncan Speakman and Nicola Canavan, among others. The program is divided into several sections such as D-Stable, Lecturama and What Next for the Body; the latter will then continue at Arnolfini until February 2011. Having participated in Inbetween Time in 2006 (RT72), this year RealTime will produce a special e-dition of reviews and articles from the festival to be published online in the second-last week of December. Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue, Dec 1-5 2010; http://inbetweentime.co.uk/

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

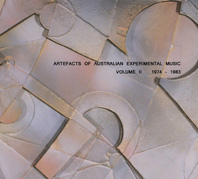

artefacts of australian experimental music volume II 1974-1983

2CD

Shame File Music SHAM056

www.shamefilemusic.com

Three years after the release of Volume I (which covered the years 1930-1973), Melbourne-based writer, artist and historian Clinton Green has produced a second compilation documenting Australian experimental musical activity. Covering the period from 1974 to 1983 it represents a vastly different economic, political, aesthetic and technological landscape from its predecessor: disillusionment with the 60s countercultural “revolution,” the fallout from the Whitlam dismissal, the emergent punk/post-punk nexus and the increasing availability of electronic equipment are all evident within these recordings. As such, it is a conduit into a not-so-distant past, albeit one that Ian Andrews, as quoted in the liner notes, described as “the lost decade.” Without any pretence of being exhaustive (let alone conclusive), the pieces and artists that Green has selected, along with his copious liner notes, are an attempt to rectify this situation; not only for students of the era, but for anyone interested in experimental arts practices in this country and in music in general.

There are a couple of factors that distinguish the music found on Volume II from the earlier compilation, one of which might be summed up in the phrase “less Cage, more collage.” Where previously adventurous composers had cleaved closely to the edicts of pre-eminent American composer John Cage, by the 1970s many of the precepts of “capital E” Experimental music—aleatoric processes, indeterminacy, extra-musical sounds and improvisation—had been well and truly internalised by artists and audiences alike. This allowed for their redeployment both within and across aesthetic schemes that intersected with a variety of agendas, be they musical, technological or social. Early works by The Loop Orchestra, Severed Heads and Ian Hartley combine tape loops and cut up procedures, appropriation and electronic sounds, encountering musique concrète, pop, field recording and radio along the way. Performers in Ron Nagorcka’s Atom Bomb use toy instruments and domestic tape recorders in a live performance that builds into a multi-layered, multi-directional sound. Minimalist repetition is combined with pop music’s own forms of reductionism by Essendon Airport and tch, tch, tch/tsk, tsk tsk (the symbol that is the correct nomenclature being unreproducible here) before being pounded to pieces with noisy “anti-musical” fervour by The Primitive Calculators.

Secondly—and this pertains mainly to pieces from the 1970s—the relationship between artists, infrastructure and institutions is at times quite marked. Tristram Cary’s Soft Walls and other pieces by Carl Vine and Ros Bandt are recordings from an era when synthesizers were expensive items, and access to them was largely through university music departments, which would doubtless act as gatekeeper when it came to their use. As such these works present a more “classic” approach to electronic composition. In stark contrast is the Forced Audience project of Gary Warner that produced tape collage and appropriation works while operating outside the institutional system, which explicitly challenged the formal relationship between artist, audience and content. Although electronically generated and manipulated sound is far more prevalent on this set than the earlier volume (with the vast majority of pieces here overtly utilising electronics beyond recording), the economics and politics of using those technologies is manifest here both in the music and the means by which it is produced: the “do-it-yourself” credo so often attributed to the punk movement has been a perennial in experimental arts.

Apart from those already mentioned, works from a wide array of significant performers and composers are featured, among them Jon Rose, Ernie Althoff, Ian Andrews, Warren Burt and renowned Mebourne guitarist Dave Brown (in the group Signals, with David Wadelton and Chris Knowles). However, it’s the inclusion of more obscure acts such as Justinstink (Justin Butler), Voigt/465 and Purple Vulture Shit, along with soundtracks by Arthur Cantrill, the location recordings of Les Gilbert and the whirly instruments of Sarah Hopkins, that not only make this a valuable release, but helps to broaden our understandings of what constitutes experimental music in Australia.

Peter Blamey

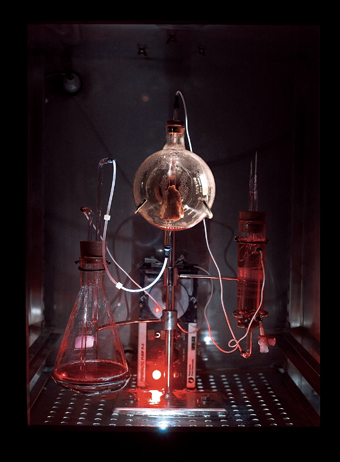

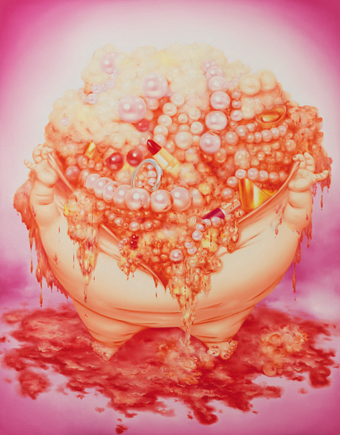

Societas Raffaello Sanzio, BR#04, Tragedia Endogonidia IV Episode

Romeo Castellucci and his Societas Rafaello Sanzio collaborators have produced some of the most seductive and enigmatic performance masterworks of recent times, epic conceptions and disturbing realisations on a scale not experienced since the first showings of the Robert Wilson “operas” with which they share a totally immersive sense of dream, if in radically different ways.

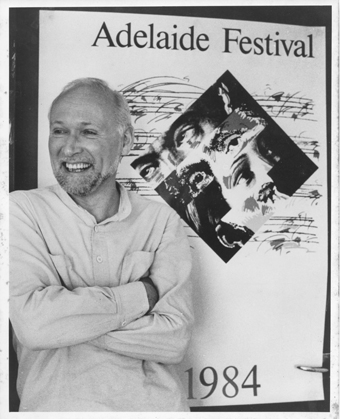

My first encounter with the company was the 2000 Adelaide Festival showing of Giulio Cesare, a nightmarish re-working of Shakespeare, Plutarch and other sources in which the oratory of Mark Antony and Brutus is hampered by the very real disabilities of the performers and the wasteland of the post-assassination civil war is a junked-out, anorexic apocalypse for our own times. Genesi: From the Museum of Sleep, at the 2002 Melbourne Festival, grimly reviewed our origins in terms of Madam Curie’s discovery of radium, a child’s Auschwitz (Castellucci’s own offspring performing) and an account of the Cain and Abel story. Richard Murphet wrote: “It is the lasting power of Genesi that its response to the ‘destiny of the inhabitants of the world’ (Castelluci, festival program) is so tough-minded, so terrifyingly lyrical, so unpredictably indirect in its creativity and so openly and quietly scandalised by the tragic consequences of the original act of creation” (RT52).

Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

photo Raffaelli

Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

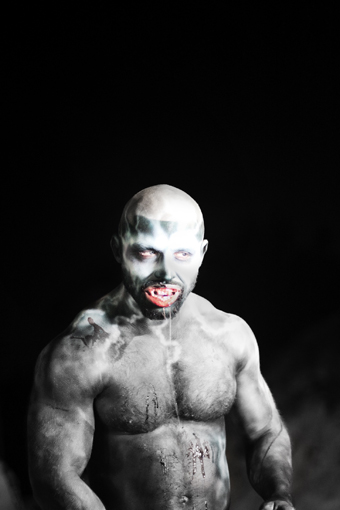

Hey Girl!, a production on a smaller scale seen at the 2008 PuSh International Performing Arts Festival in Vancouver, was typically visceral and visually inventive, if relatively literal for a Castellucci creation. Its apparent sexism was much debated during the festival (our RealTime-PuSh workshop yielded five reviews). Other works seen by RealTime writers have included Purgatorio at the 2008 Avignon Festival and Tragedia Endogonidia, BR#04 Brussels (three brief reviews, two from the 2005 Melbourne Festival and one from the 2003 KunstenFestivaldesArts, Brussels).

Max Lyandvert and Jonathan Marshall provide detailed backgrounds to Tragedia Endogonidia and Genesi respectively. Sydney-based composer and sound designer Lyandvert, who has worked with Societas Rafaello Sanzio here and in Europe, describes in fascinating detail the origins, images and meanings of the 11 Tragedia Endogonidia works and their associations with particular cities. Marshall interviewed Castellucci about Genisi, covering a range of subjects, including the director’s use of non-professional performers: “In truth, every body is worthy of being on stage. For me there are no deformed bodies, but only bodies with different forms and different beauties, often with a type of beauty that we have forgotten.”

Marshall also explores with Castellucci the pivotal relationship between image and sound in his work: “[Composer Scott] Gibbons has developed sounds using a numerical technique called ‘granular synthesis’ which he applied to various photographs I sent him every week from my home…[He] has thus been able to give voice to certain images which I felt were intimately connected with the show. From this, some scenes were born with sounds, and other sounds were born from certain scenes.”

In a revealing discussion about violence, creativity and tragedy in his work, Castellucci comments: “Genesis frightens me much more than the Apocalypse. The terror of pure possibility is there in this sea open to all possibilities.” The sentiment resonates with the experience of witnessing a Castellucci creation—awe at what can still be realised on a stage, “so unpredictably indirect in its creativity.”

Castellucci’s Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso, superbly filmed by Don Kent, is now available on an arte editions DVD. The cast includes Sydney performance maker Jeff Stein, who invited Societas Rafaello Sanzio member Chiara Guidi to Campbelltown Arts Centre recently to speak about theatre and childhood and run a workshop involving local artists and children. Bryoni Trezise, who reports on the event, in 2009 experienced Guidi and Scott Gibbons’ sonic performance installation Augustinian Melody at the Santiago a Mil festival in Chile. For more on Castellucci and his collaborators there’s also the book The Theatre of Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio by Claudia Castellucci, Romeo Castellucci, Chiara Guidi, Joe Kelleher and Nicholas Ridout (Abingdon and New York, Routledge, 2007).

Keith Gallasch

reviews

a childhood of theatre

bryoni trezise: chiara guidi, campbelltown arts centre

history’s imprints

bryoni trezise: chiara guidi

hey girl! dark discoveries

eleanor hadley kershaw

hey girl! ache and awe

alex ferguson

hey girl! art object

andrew templeton

hey girl! the painted stage

anna russell

hey girl!:evolving symbols

meg walker

the art of punishment

carl nilsson-pollas: romeo castelluci’s purgatorio, avignon

kinds of truth

john bailey: tragedia endogonidia, br#04 brussels

images that hold

adam broinowski: tragedia endogonidia, br#04 brussels

castelluci on film, in person

realtime

theatre of remnants: castelluci

max lyandvert: tragedia endogonidia

time, intimate and epic

lucy taylor, tragedia endogonidia, br#04 brussels

genesi: from the museum of sleep

richard murphet

realtime@2000 adelaide festival: giulio cesare, oratory & suicide, RT36, p22

keith gallasch

interview

the castelluci interview: the angel of art is lucifer

jonathan marshall

Kym Vercoe, Seven Kilometres North-East

photo Heidrun Löhr

Kym Vercoe, Seven Kilometres North-East

VERSION 1.0 FIRST FOUND FAME THROUGH THEIR GROUP WORKS, SUCH AS CMI (A CERTAIN MARITIME INCIDENT) AND WAGES OF SPIN. MORE RECENTLY, HOWEVER, THEIR SOLO SHOWS HAVE BEEN GARNERING ATTENTION: PAUL DWYER’S BOUGAINVILLE PHOTOPLAY PROJECT AND NOW KYM VERCOE’S SEVEN KILOMETRES NORTH-EAST. LIKE DWYER’S, VERCOE’S WORK IS ABOUT HER AMBIVALENT ENTANGLEMENT WITH ANOTHER COUNTRY, TOLD THROUGH AN ELEGANT COMBINATION OF STORY, SONG AND IMAGE.

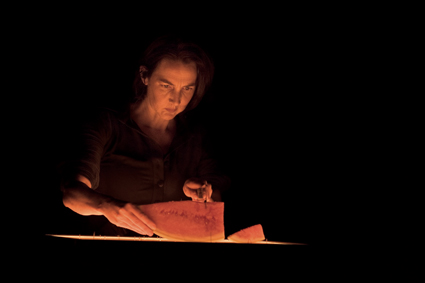

Sitting in the slightly dingy surrounds of the Old Fitzroy, spectators see a small stage with two stones, which double as stools; on the opposite side is a shelf with tea, beer and a few books. In the background is a large white wall, onto which the image of a rotating propeller is projected. Vercoe stands on a small stage above this, pegging pillowcases to the four clotheslines that stretch across the upper reaches of the space. Once she has completed her task she enters the lower stage via a door in the middle of the screen.

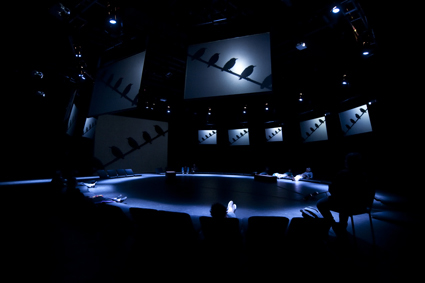

From here Vercoe introduces herself and her home away from home—Bosnia and Herzegovina—a country with which she feels an inexplicable, and inescapable, connection. She has visited three times, in 2004, 2008 and 2010; or, as she puts it more poetically, in autumn, summer and spring. She has more than 17 hours of video footage from these visits which video artist Sean Bacon has helped her to edit down to a more modest, though still mesmerising 80 minutes. Throughout the play, images of rivers, mountains, flowers and birds dance before our eyes. In fact, birds are a recurring motif, with each section named after a particular species and aligned with a series of video tapes. In between each section, a “songbird” sitting in the audience stands and performs a folk song.

Tapes 1-3, titled Prologue, deal with her first visit: there is a party; a man; some linguistic misadventures; and the discovery of Ivo Andric’s book The Bridge Over the Drina. Tapes 4-7, The Swallow (the symbol of return), deal with Vercoe’s second trip and her visit to this famous bridge in Višegrad. In one striking moment she spreads coffee grounds on the floor in the shape of the bridge and enacts a passage from Andric’s book, her lithe body dancing along the bridge. Towards the end of her trip, in Tapes 7-11 The Cormorant (sometimes a symbol of deception), she visits Vilina Vlas, which is located roughly seven kilometres north-east of Višegrad (hence the title). The hotel is nice enough, however when she returns home she discovers that it was a rape camp during the Bosnian war, a fact not mentioned in the guidebook. This discovery prompts her to email the author. More significantly, it prompts the slow, sickening realisation that in order to make peace with herself (and perhaps to make this piece of theatre), she is going to have to return to the scene of the crime.

Kym Vercoe, Seven Kilometres North-East

photo Heidrun Löhr

Kym Vercoe, Seven Kilometres North-East

The final section, titled The Nightingale (whose song is sometimes interpreted as a lament), sees Vercoe back in Bosnia where she meets the author of the guidebook as well as journalists who covered the war. When it all proves too much, she puts on her headphones and listens to A-Ha’s “Take On Me.” The music blasts through the space as she dances her way across the floor, smearing the coffee bridge in the process. The movements resemble Vercoe’s previous dance, which we had assumed was her interpretation of Andric, but thanks to video footage in the background we can now see that she has borrowed the moves from someone we assume to be a Bosnian busker.

For the most part, Seven Kilometres North-East is thoughtful, beautiful and beguiling, so if there is a criticism to be made of the performance, then it is a criticism of memory culture more broadly. Vercoe’s easy (over)identification with the victims—unable to sit where they might have sat, thinking about how her own unknowingness echoes theirs—means that her role, and ours as bystanders go largely unexamined. Though we may not have stood and pegged clothes on the line while looking at the rape camp down the hill, we are all complicit in the crime to varying degrees. Indeed, this is one of the insights of the show, which could be pushed further—innocent, ignorant, distant and belated, it may be that there are many types of bystanders, many modes of complicity.

There are also many modes of erasure. When Vercoe contacts a local history centre for the information about the women who were in Vilina Vlas, their names cannot be released—one final annihilation, as she puts it. Similarly, when the new guide to Bosnia is released, the entry on Vilina Vlas has not been amended but simply deleted.

On that note, Vercoe strips off, opens the door and steps into the shower. The image of the bridge is projected onto her naked back as she washes herself clean of sins that were not hers, are not ours and yet are everyone’s. Eventually she steps out of the shower but the water continues running, weeping, cleansing—until finally, it stops.

Version 1.0, Seven Kilometres North-East, devisor and performer Kym Vercoe, video artist Sean Bacon, dramaturg Deborah Pollard, musical director Sladjana Hodzic, lighting designer Emma Lockhart-Wilson, production manager Frank Mainoo, producer David Williams; Old Fitzroy Theatre, Sept 30-Oct 6

This article was first published online Nov 8, 2010.

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 33

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

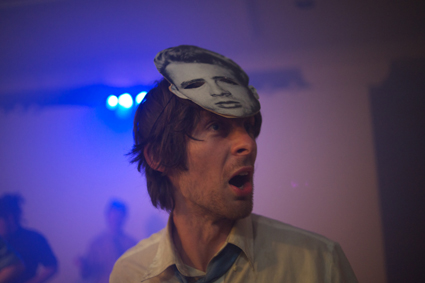

Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque, You Little Stripper

photo Alex Davies

Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque, You Little Stripper

SEARCHING FOR A SUITABLE NAME FOR A NEW WAREHOUSE ARTS VENUE, CO-FOUNDER LUCAS ABELA DECIDED TO COMMEMORATE ONE OF THE SEEDIER MOMENTS OF SYDNEY’S HISTORY: THE ‘ALLEGED’ SHOOTING IN THE 1980S OF WARREN LANFRANCHI BY POLICE OFFICER ROGER ROGERSON IN A CHIPPENDALE BACKLANE.

The elaborate full titling—Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque—took a little practice to get rolling off the tongue, but in retrospect it seems impossible to imagine it being called anything else: the reference infused the place with the spirit of the underworld and the underground. It seems equally impossible to imagine the Sydney arts scene in the mid 2000s without it. But like all good things, especially illegal performance venues, it came to an end (after an impressive five years) and filmmaker Richard Baron was there to document its death throes.

In the final phase of Lanfranchi’s there was a significant increase in performance events, as opposed to the music (admittedly often performative) that had been more prominent in the earlier days of the venue. Grainy footage captures the raucous freedom of performance nights such as Cab Sav; the incredibly popular Wonka live cinema experience, developed in the venue; and the antics of people doing strange things with electricity that is DorkBot. The debauchery reaches its zenith with the Marrickville Jelly Wrestling Federation—people slip-sliding all over each other in various states of costume and nakedness, performing acts of frenzied exhibitionism. Having experienced quite a lot of ‘serious’ (ie clothed) experimental music at Lanfranchi’s, I was slightly saddened that this aspect of the venue was not so well represented in the film, but in fairness, it is a document of the last 60 days of the venue when perhaps the mayhem was reaching its peak.

However it’s not all good times. Baron’s camera is there when the residents are being harassed by the landlord’s heavy, who comes each morning to disconnect the electricity in an attempt to speed up the eviction when they are still legally entitled to be there. One of the residents is subsequently electrocuted (fortunately not fatally) trying to reconnect power and the camera shows us his blackened hand and singed eyebrows. The camera is also secretly left on during heated discussions with council representatives and police giving us audio snippets and groin shots. But rather than labouring the negatives of the experience, they are included as just part of the whole package.

Baron conducts informative interviews with residents such as Phoebe Torzillo, Pia van Gelder and Tega Brain who each offer glimpses into the different micro-cultures that clustered around the venue. Not surprisingly Lanfranchi’s co-founder Lucas Abela is highlighted, with some gruesome footage of the glass playing/smashing performance that he developed in the space after finding an old window pane lying in the corner—an act he has subsequently toured worldwide. Alex Davies, another co-founder and resident to the bitter end, is given less personal screen time, but offers much to the film through his video and photographic documentation, succinctly capturing the essence of many of the events.

Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque, Lanfranchi’s residents

photo Simone Schelker

Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque, Lanfranchi’s residents

Initially I was concerned that the documentary might suffer from amnesia about venues and activities which preceded, or ran concurrently with Lanfranchi’s. (In an opening interview Abela insists that there were galleries but no venues before Lanfranchi’s—perhaps technically true, but many of the galleries had strong histories as performance venues as well.) However as the documentary unfolds, Baron pieces together anecdotal histories digging up the Evil Brotherhood of Mutants (a posse of Clan Analogue members) who occupied the same space in the 90s. He also works in references to some of the many other artist-run spaces around town past and present: Imperial Slacks, Space 3, Hibernian House, China Heights to name a few. (The accompanying website also provides a comprehensive list of artist-run spaces.)

The film also takes steps towards analysing the complicated interplay of the underground and mainstream art scenes. A topic in several of the interviews is whether to work within or without the system, or whether you can balance a bit of both. That Lanfranchi’s’ demise roughly coincided with the opening of CarriageWorks is an irony also not lost on the filmmaker. However he cleverly allows CarriageWorks’ then CEO Sue Hunt to make his point for him, as she speaks of how the complex will be “a place for creativity and innovation,” and then discusses how “thrilled” she is to include Channel 10’s “contemporary dance piece” So You Think You Can Dance.

This self-funded film project took almost three years to complete. In contrast to much of the outrageous work undertaken at Lanfranchi’s, Richard Baron’s approach is stylistically straightforward, letting the footage, both his own and that accumulated from a range of sources, speak for itself. Underscored by the vivifying soundtrack drawn from many of the artists involved in the space, the film conveys a tangible sense of the moment. Grounding this, the considered editing of interviews ensures that the film is not just the documentation of good times past, but also offers some analysis of the broader Sydney arts culture. Of course there are new (and ongoing) spaces that continue to nurture Sydney’s underground/underworld, and each have their own flavour…but the sheer seediness and reckless abandon of Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque so far remains unrivalled.

Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque – The Documentary, Richard Baron, Bitterman Films, www.lanfranchismemorialdiscotheque.com/

Lanfranchi’s Memorial Discotheque – The Documentary won the Director’s Choice Award at the 2010 Sydney Underground Film Festival, Best Documentary at the 2010 Melbourne Underground Film Festival

This article was orginally published online, Nov 8, 2010.

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 22

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

en masse

photo Matt Nettheim

en masse

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN (JACK ARNOLD, 1957) CONTAINS ONE OF MY FAVOURITE MOMENTS IN SCIENCE-FICTION CINEMA. AFTER HAVING BEEN EXPOSED TO A MYSTERIOUS RADIOACTIVE CLOUD, THE FILM’S PROTAGONIST, SCOTT CAREY, FINDS HIMSELF PHYSICALLY SHRINKING AT AN ALARMING RATE. DOLL-SIZED, HE FLEES TO THE HOUSEHOLD BASEMENT WHERE HE IS FORCED TO NEGOTIATE A FORMIDABLE ARRAY OF ONCE FAMILIAR DOMESTIC OBJECTS (CRATES, MATCHBOXES, PINS, MOUSETRAPS) AND DO BATTLE WITH THE FAMILY CAT AND OTHER PREDATORS.

Struggling up from the basement to the garden, Carey realises that he might soon become ‘infinitesimal’. He looks up the night sky whereupon tiny and immense phenomena suddenly become intertwined. As his body dwindles to the sub-atomic level, the camera shifts skywards to reveal grand-scale celestial bodies and astronomical vistas. The garden and Carey dissolve into a succession of stars while Carey’s voice-over reminds us that even the “smallest of the small” matters in the larger scheme of things. For myself, what makes this sequence such a powerful and incredibly poetic moment is its refusal to set-up the ‘large’ and the ‘small’ as oppositional perceptual terms. Indeed, Carey himself comes to understand perceptual scale as relative: “the unbelievably small and the unbelievably vast eventually meet”.

The mobile and sliding scale of perception is by no means specific to the realm of science-fiction?just think of how tiny things such as a childhood treasure box or dollhouse can contain endless imaginative possibilities while immense landscapes or intricately detailed aesthetic objects hold the capacity to make us feel small, inferior or insignificant, by comparison. Our perception of the large within the small or the vast within the miniature alerts us to the dynamism that is seeing itself; the ways in which embodied encounters can unleash a sense of eeriness or displacement as well as liberation in aesthetic experiences, through the power of what the experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage once beautifully described as the sheer ‘adventure of perception’.

Perceptual scale—through the experience of visual and sonic shifts between the grand and the miniscule, the intimate and the elusive—was fundamental to the two mixed media installations, en masse and epi-thet, that were presented at Arts House for this year’s Melbourne International Arts festival. Neither work, however, could justly be described as awakening the kind of sensual engagement or intellectually curiosity that might be befitting of Brakhage’s perceptual ‘adventure’. While filled with intriguing conceptual promise, the conjunctions of imagery, sound and setting that occurred in each installation either failed to deliver upon their intended poetics, make maximum use of our visual and sonic immersion within their respective spaces or induce a perceptual de-familiarising of the everyday.

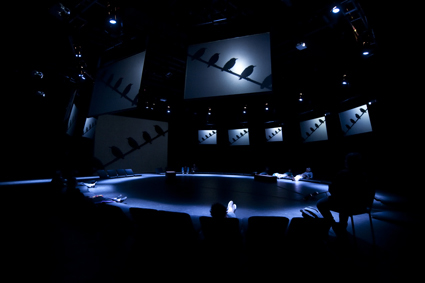

en masse

En masse is the result of an artistic collaboration between Australian recorder virtuosi, Genevieve Lacey, and UK filmmaker Mark Silver. Silver provided the footage for its multi-channel projections which display migrating starling birds, shot against a stark grey sky at sunrise and sunset. Silver’s footage is luminous and evocative, with the birds initially appearing as distant and almost abstract patterns, only to resolve into closer figurative detail (beaks, feathers) as the work unfolds. From a series of initial musical improvisations to which other musical collaborators (led by Lawrence English) were invited to respond, Lacey has designed a purpose-built soundtrack to accompany the footage. That electroacoustic track is synced to the imagery of the flocking starlings, at the same time as Lacey performs live within the half-hour staging of en masse.

While touted as ‘part concert, part installation, part film’, en masse does not make for a cohesive fit. That disharmony has nothing to do with Lacey’s obvious skills as a performer/composer nor with Silver’s often stunning footage. Rather, it arises because the different elements of en masse (performance, sound, time-based installation) are in phenomenological conflict with one another. During the performance Lacey’s spotlighted presence, gently wandering about the space, actually distracts from fully attending to the projected imagery or attuning oneself to the soundscape. Similarly, the clunky black-box installation feels at odds with the artistic intent of creating a heightened perceptual state for its audience. Ushered into a circular room, we must lie down to experience en masse; yet, its projections are of variable sizes and the audience is only able to see what is directly in front of them. The effect is disempowering rather than sensually immersive, effectively restricting and minimising our field of vision to 180 degrees. In this performative mode, the work seems to be unsure whether it is intended as theatre or installation and its uneasy mix of media ruptures our affective and mnemonic engagement with the sights and sounds on show. However, en masse was also viewable as an installation without performance during the day. On these occasions, the audience was largely left to their own devices and could potentially view the work from a range of positions and as a purely audiovisual experience.

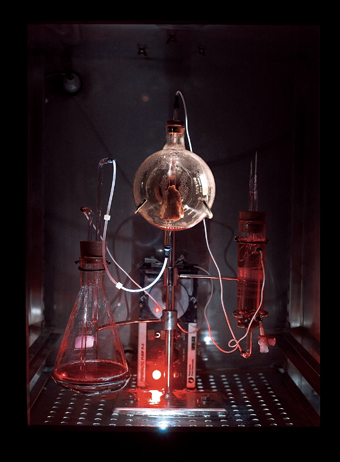

epi-thet

photo Dean Petersen

epi-thet

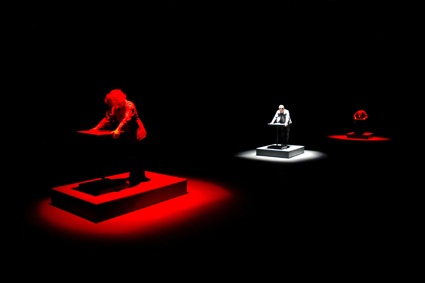

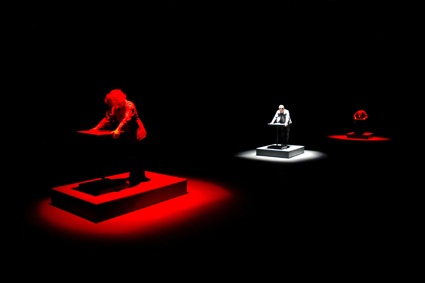

epi-thet

Epi-thet (Madeleine Flynn, Tim Humphrey and Jesse Stevens), by contrast, makes highly considered use of the Meat Market in its sound-based installation. Upon entering the work, sounds emanate from all sides, ping-ponging and ricocheting through the vast space. The visitor encounters three platforms lined up horizontally, each suffused with a soft red light as the piece rests in its ‘inactive’ mode. Attached to each platform are a series of mounted microscopes. As you step onto the platform, the light abruptly changes to a white spotlight—chromatically alluding to the fact that both you and the work are here to engage in a mutual performance. The sound and light shows that accompany each viewing of the microscopes are unique; generated by the height and posture of the participant, as well as the particular time of day.

Yet for all its insistence on individual composition and the presence of the participant as being crucial to the work, epi-thet remains eerily disembodied and inaccessible. The sounds that are generated are often indistinguishable, lacking in expressivity or material sources in the world. The linkages between the ‘sonification’ of medical research data, the interactivity of the piece and the microscope animations (tiny bird-like objects accumulating in patterns, with text fragments) are also unclear. Instead of amplifying our engagement with the work through the lures of sound—by playing to the fact that, as French theorist Michel Chion suggests, sound itself is decidedly un-framed and able to ‘fill’ a space in ways that an image cannot—epi-thet ends up subjugating our sonic involvement to the tiniest of visions. As we struggle to discern and understand the miniscule animations contained in its microscopes, sound drops out of the experience at the expense of vision.

Given their perceptual mismatches between the large and the small, as well as vision, space and sound, it is disheartening to find that the conceptual promise of these works has not been realised.

en masse, composition and performance Genevieve Lacey, film Marc Silver, installation sound Lawrence English, musical collaborators Steve Adam, Taylor Deupree, Christian Fennesz, Ben Frost, Nico Muhly, dj olive, lighting designer Paul Lim, Trafficlight, systems designer Pete Brundle, nice device, costume designer Paula Levis; Arts House, Oct 19-23; epi-thet, creators Madeleine Flynn, Tim Humphery and Jesse Stevens; Arts House, Oct 19-23; Melbourne International Arts Festival, Oct 6-22

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. web

© Saige Walton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

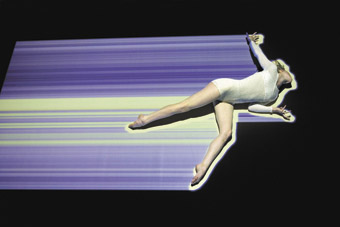

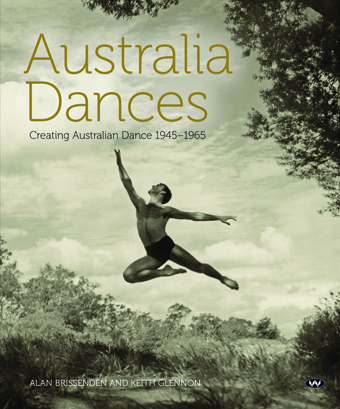

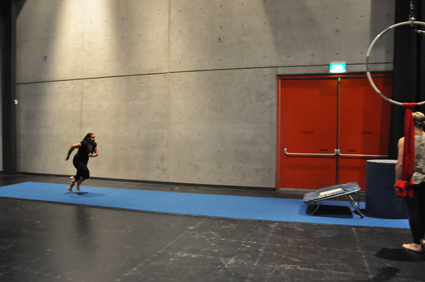

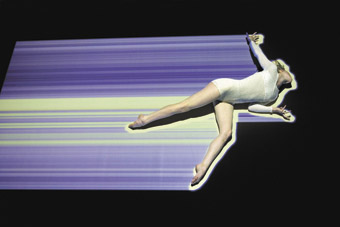

BalletLab at the Australian Ballet Studios in development for Aviary

photo Jeff Busby

BalletLab at the Australian Ballet Studios in development for Aviary

JUST BACK FROM TROY, NEW YORK STATE, VIA SAN DIEGO, ARIZONA AND DUSSELDORF, PHILLIP ADAMS HAS BEEN OFF THE BEATEN TRACK OF LATE. I MEET HIM AS HE PREPARES TO DEPART FOR ANOTHER DESTINATION—TIJUANA, MEXICO. WE TALK ABOUT GLUCKSCHWEIN, THE PRODUCTION HE IS MAKING WITH THE MEXICAN DANCE COMPANY LUX BOREAL. THE PIECE WILL FEATURE A SHEPHERD, DANCERS DRESSED AS SHEEP, 50 MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC ON STAGE PLAYING TOY PIANOS AND SOME RITUALISTIC SACRIFICE.

festival de mexico

Wild as it may sound, Gluckschwein is actually part of a formal exchange between Mexico and Australia, run by the very respectable Australia Latin America Foundation, with dedicated funding devolved from the Australia Council. Over two years from 2010 to 2011, there will be residencies in dance, physical theatre and music, “aimed at sharing skills and creating new work between Australian and Latin American artists and artistic companies.” David Clarkson of Stalker began the initiative with a physical theatre project in Colombia and Roland Peelman of The Song Company is working in Guadalajara, Mexico. Alongside Adams, another Melbourne based choreographer, Rebecca Hilton, is working with Mexican dance company La Lagrima in Hermosillo.

Phillip Adams has been to Tijuana twice already. The four weeks of rehearsals to come will precede a final visit to prepare the work for its world premiere at the Festival de Mexico in March 2011. He is inspired by the openness of the Mexican dancers, who recovered well from his initial attempts to freak them out. Broken in by running naked through the streets and confronting some of Adams’ more extreme preoccupations, they were quick to overcome cultural barriers and throw themselves into the experience.

Gluckschwein is an echo of the parallel production, Above, that Adams will make with his own company BalletLab. It addresses similar themes of death, mortality and transcendence. For over a decade, Adams tells me, he has been pursuing related ideas. He traces an arc through the 1999 production Amplification (RT33) and its 2009 companion piece Miracle (RT93) that encompasses all his work. “Above will be the closure of this journey,” he says, “Why not finalise this enquiry into sex, life and death with a look into the afterlife?”

Adams saw work in the Festival de Mexico last year and is confident that audiences will enjoy the extremity of his vision and that the material will touch a chord. He has not attempted to incorporate specific cultural references but is sure that they will emerge in the work that he has devised with the Mexican dancers. Whilst Gluckschwein will tour for Lux Boreal and already has dates in San Diego and parts of Mexico in 2011, Adams will focus upon his BalletLab work as soon as he is back from Tijuana.

mona foma

Adams will spend the latter part of this year developing Above; which will make its world debut at MONA (Museum of Old and New Art) FOMA (Festival of Music and Art) in Hobart, Tasmania in January 2011 (see preview). Commissioned by MONA, Above will be presented as part of a trilogy, alongside Amplification and Miracle. These works will constitute the only dance presentations in the festival, which is curated by Brian Ritchie of Violent Femmes and characterised by a hard rocking, left-field, internationalist aesthetic. This prominence is testimony to the long-standing relationship between BalletLab and MONA founder and art collector David Walsh, whose own much-anticipated museum will be opening its doors to the public at the same time as the third “MOFO” festival. Adams is proud to be so closely associated with what he anticipates to be “a landmark event for the arts in Australia.”

Walsh’s previous support for BalletLab includes a pivotal investment in the New York State residency that led to the creation of Miracle. “This level of patronage and prestigious recognition is highly unusual,” says Adams. He is extremely excited by this opportunity to show his works together in the way in which they sit so coherently in his mind. “Above will be more of an event than a performance,” he says. “It will have the same impact as Amplification and Miracle but on a larger scale. Like Gluckschwein, Above will feature 100 toy pianos on stage and an element of public participation. There will be biblical motifs and an exploration of sacrifice.”

In his press material, Adams talks about the work as “a fairytale in the guise of a modern road movie.” When I ask about the artistic collaborators in the work, he tells me that he will only work with the dancers, and that he will undertake all other design elements, taking the design of Miracle as the starting point. “I am looking for a raw, pared back aesthetic for this piece,” he says. This makes Above unusual for Adams, whose strong mission for BalletLab has always benefitted from the input of first class composers, costume designers and other design professionals such as architects.

ballet and beyond

Whilst Adams has no current invitations to present the entire trilogy elsewhere, he is confident that such offers will come. Amplification, the work that really broke BalletLab on to the international scene in 2000, with its sex and death concerns and brutally beautiful dancing, will receive another outing at Melbourne’s Malthouse in the Dance Massive festival in March 2011. Miracle, the piece that premiered at Melbourne’s State of Design Festival last year, was recently shown at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Centre (EMPAC) in Troy, New York State, in its Filament festival. EMPAC presented Amplification in 2007 and supported the Miracle residency in 2008, and this year, demonstrated their ongoing investment in BalletLab with two presentations of Miracle and an artist talk. EMPAC also worked with the company to invite other North American presenters to see the work. Adams hopes that further US touring will emerge from his long-standing relationships with the region and is also pursuing opportunities in Europe. His recent showcase presentation at the Internationale Tanzmesse NRW in Dusseldorf, a large dance platform and networking event, was an unusual move for an Australian company, but one that he is hoping will lead to commissions to make work with international companies and invitations to tour the BalletLab repertoire.

And Phillip Adams continues to add to that repertoire, with another work to premiere in Australia in 2011. Aviary is the result of a partnership with the Australian Ballet instigated through the Australia Council’s Interconnections program, which encourages a sharing of resources between arts organisations large and small. In 2009 Adams brought his contemporary dancers into the studios of the Ballet to work with classically trained dancers. Inspired by the music of Oliver Messiaen and by themes of war, masculinity and royalty, all overlaid with conceptual ideas about birds, the choreography pursued a meeting point of contemporary and classical.

A second development introduced the “dandy” aesthetic, drawn from a fruity palette of references from Beau Brummell to Gilbert and George. The collaborators for the final development, to take place in December this year, are a very BalletLab-like group, including milliner Richard Nylon, visual artist Gavin Brown and fashion designer Toni Maticevski. Adams says, “We are all of a generation; all Melbourne dandies.” Adams himself will perform in the piece, alongside five BalletLab dancers and one graduate of the Australian Ballet School. Aviary will be a large scale work for the proscenium arch, fitting, Adams says, “of the prestige of the relationship with the Ballet and the ambition of the piece.” This grand vision presages exciting times ahead for followers of the inimitable Adams and his BalletLab.

BalletLab, www.balletlab.com; MONA FOMA, Hobart, Jan 14-20 2011, http://mofo.net.au/

This article was originially published online, Nov 8, 2010.

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. web

© Sophie Travers; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Junee Train, Rolling Stock

photo courtesy of Wired Lab

Junee Train, Rolling Stock

rollin, rollin, rollin

If you feel like an excursion to the country, or if you live in regional NSW, then you should head to Junee on Saturday November 20 for Rolling Stock, a range of site-specific installations experienced while riding though the countryside on a heritage locomotive. Many of the installations will be the result of a week of residencies in which artists collaborate with the local Junee community and curator Sarah Last has brought together an impressive list of contributors including Alan Lamb, Kate Murphy, Joel Stern, Ross Manning, Garry Bradbury, Justy Phillips and Ryszard Dabek, Dave Noyze and Shannon O’Neill. The special guest is UK artist Chris Watson, ex-Carbaret Voltaire band member turned field-recordist, who will present ‘El Tren Fantasma – The Ghost Train’, reworking field recordings he has made for Rick Stein’s documentary Great Train Journeys, into a surround sound experience on the train. The PVI collective will also be offering their participatory tug-o-war and while you travel you will be entertained by Australia’s own king of country Renny Kodgers. When you alight from the journey, the party continues with a Rockabilly band at the Junee Licorice and Chocolate Factory. Rolling Stock, Nov 20, 12pm–12am, journey starts at Junee Railway Station; www.rolling-stock.org (bookings essential)

Change, 2005, Blair Trethowan

photo courtesy of the Monash University Museum of Art

Change, 2005, Blair Trethowan

muma

New York may have MoMA but Melbourne has a newly reinvigorated MUMA: the Monash University Museum of Art. The new museum, designed by Kerstin Thompson Architects, “combines increased gallery space and capacity, a landscaped sculpture court and a major architecturally-scaled public art installation by artist Callum Morton, titled Silverscreen” (press release). To celebrate, the museum is hosting a new exhibition called Change. Sourced entirely from the extensive Monash University Collection, the inaugural exhibition brings together more than 75 major works by Australian contemporary artists—from painting to photography, installation and performance. Change places work by John Perceval, John Brack, Charles Blackman and Roger Kemp alongside more contemporary work by Mike Parr, Tracey Moffatt, Susan Norrie, Marco Fusinato, Lydia Galbal Gjinabalyi, Raquel Ormella, Daniel von Sturmer and Blair Trethowan. Change, Monash University Museum of Art, Oct 27-Dec 18; www.monash.edu.au/muma/

Byron Perry, Anthony Hamilton, Simon Obarzanek, Ross Coulter, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc

photo Untrained Artists

Byron Perry, Anthony Hamilton, Simon Obarzanek, Ross Coulter, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc

totally awesome

The phrase may recall the 1980s, but the Awesome International Arts Festival for Bright Young Things is happening here and now, meaning Perth in November 2010. Chief among the attractions is Lucy Guerin’s Untrained, which premiered in Melbourne in 2009 and was reviewed in RT90. Other intriguing performances include Track, a performance in which Vincent de Rooij, Udo Akerman and Daan Mathot (Netherlands) blend film and theatre to create a short film before your very eyes. “Udo’s miniature film studio (which happens to be a sea container) captures the action on camera in real time, using everyday objects as sets and characters, and is streamed live via projection on the opposite end of the sea container” (website).

There is also The Library of Nearly Lost Moments, which is to be installed at the State Library of Western Australia. The audience is invited to “check their pockets and see if there’s anything you can leave behind to preserve a moment in time…a train ticket? A sweet wrapper?” (website). For junior film lovers there is a series of animated films thanks to a partnership with the Los Angeles International Children’s Film Festival. Finally there is the Home Ground installation and exhibition, both of which are the result of a year-long program involving young people from 11 regional and remote communities. Awesome International Arts Festival for Bright Young Things, Perth, Nov 19-28; www.awesomearts.com/festival

Dancing Dreams

photo courtesy of the Brisbane International Film Festival

Dancing Dreams

bring back the biff

If you miss the animated films in Perth then you may be interested in the animation programs at this year’s Brisbane International Film Festival. First up, there’s the International Animation Showcase, which features 13 of the finest short films from the archives of Britain’s Animate Projects, which has spent the past 20 years funding and producing animation. BIFF has also secured Sylvain Chomet’s (The Triplets of Belleville) new animated film The Illusionist, which is based on an unproduced script by French comic Jacques Tati, who wrote it between Mon Oncle and Playtime. But for those who like their bodies “live,” and not animated, perhaps Dancing Dreams will appeal. The documentary focuses on Jo Ann Endicott, an Australian dancer who spent roughly 30 years with Pina Bausch’s company, as she works with a group of Germans to restage Bausch’s Kontakthof. Bausch herself appears throughout the documentary to mentor and encourage the cast—the final footage captured of the choreographer before her death in June last year. Brisbane International Film Festival, Nov 4-14; www.stgeorgebiff.com.au

power to the powerhouse

While in Brisbane you may also like to check out the Brisbane Powerhouse, which is hosting two interesting events over the coming weeks. First, there is the new exhibition Spare Parts, which brings together a diverse range of artists using prosthetic limbs as their canvas. In addition, there is Ten Hands, a new one-hour work from Topology who we’ve previously reviewed in RT93. Ten Hands apparently evolved over an extended period in the rehearsal room where the group recorded their collective improvisations, then notated the best bits which were then used “as basis of the next jam session… This process went on repeatedly, with each member adding their own development and transition ideas until a single, unified, continuous one-hour piece emerged—strong, honed, individual voices intermingled into one sinewy whole, rich in musical thought” (website). Spare Parts, Nov 8-Dec 5, Topology, Nov 14, Brisbane Powerhouse; www.brisbanepowerhouse.org

Gail Priest, Presentiments from the Spider Gardens

listening, moving and launching

We’re famous! Well, sort of. Some RealTime regulars are launching books and CDs this month. First, on November 14, there is the launch of VOICE: Vocal Aesthetics in Digital Arts and Media, edited by Norie Neumark, Ross Gibson and Theo van Leeuwen, all of whom have previously appeared in RealTime in one way or another. (We reviewed Memory Flows, an exhibition that Neumark both curated and contributed to, in RT97; read Gibson’s book The Summer Exercises in RT91; and reported van Leeuwen’s remarks on film education in RT98.) Then on November 16, there is the launch of Erin Brannigan’s Platform Paper, Moving Across Disciplines: Dance in the 21st Century. Founding director of ReelDance and now a lecturer at UNSW, Brannigan has written many articles for us over the years, most recently an introduction to our Archive Highlight on Lucy Guerin and an article on dance infrastructure in NSW (RT91). Finally our very own associate editor Gail Priest has just released her second full length CD, Presentiments from the Spider Garden, courtesy of Endgame Records. The album weaves “field recordings, vocals, instrumental material and extended digital methodologies into a haunting cabinet of curiosities” (press release). VOICE: Vocal Aesthetics in Digital Arts and Media, Ed Norie Neumark, Ross Gibson and Theo van Leeuwen, Gleebooks, Nov 14, rsvp www.gleebooks.com.au; Moving Across Disciplines: Dance in the 21st Century, UNSW, Nov 16 rsvp Jennifer Beale, j.beale@unsw.edu.au; Gail Priest, Presentiments from the Spider Garden, Endgame Records, www.endgame.com.au

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Groote Eylandt Dancers, Mahbilil Festival

photo Dominic O’Brien

Groote Eylandt Dancers, Mahbilil Festival

IT’S THE GOLDEN HOUR BY THE SHORES OF LAKE JABIRU, 300KM FROM DARWIN, AT KAKADU IN THE NORTHERN TERRITORY. AS THE MAHBILIL FESTIVAL SEGUES FROM AN AFTERNOON OF DODGEM CARS AND EXHIBITIONS INTO AN EVENING PROGRAM OF LIVE MUSIC AND DANCE, A GENTLE BREEZE ARRIVES. THIS IS THE ‘MAHBILIL’ FROM WHICH THIS LOCAL COMMUNITY FESTIVAL GETS ITS NAME, AND FITTINGLY, AS IT HITS THE GRASSY GREEN SHORES OF THE TOWN’S MANMADE LAKE, SO DO THE CROWDS.

The local miners and their families, the Bininj and Mirrar people who are the traditional custodians of Kakadu, the park rangers and outback tour operators who have been manning stalls throughout the hot afternoon, all gather before the Mahbilil Festival stage to enjoy the entertainment and to party on into the night.

In this, his third festival, producer Andrish Saint-Claire has managed to combine a smorgasbord of arts and activities where there is indeed something for everyone. From dodgem cars and waterslides to demonstrations of traditional Indigenous arts and crafts and Magpie Goose cooking competitions, variety is the order of the day.

The festival began at midday, as a family afternoon of stalls, fun rides and a showcase of performances and exhibitions by local children from all the workshops produced by the Kakadu Youth Centre through the Jabiru Area School. The atmosphere is reminiscent of the local markets for which Darwin is renowned—friendly, familiar, laid back. This is the time to sample buffalo stew and barbecued magpie goose cooked up by tour operators Andy Ralph and his wife Jen from the Kakadu Culture Camp; to chat with Kakadu rangers about killer crocs (if one ever bites your leg, punch it in the eye); and to sit with the local Bininj women as they weave their baskets out of pandanus painstakingly plucked from the bush and stripped, split and boiled up in ochre dyes over the camp fire. A casual attitude belies the deft artistry of these traditional women—and they have a canny knack, too, of always managing to find the coolest spot, anywhere, to spread out their tarp and pass the afternoon.

Goose Lagoon, Mahbilil Festival

photo Dominic O’Brien

Goose Lagoon, Mahbilil Festival

Dance was a feature of this year’s Mahbilil Festival, and again, the program was diverse. Balinese dance group Tunas Mekar, based in Darwin, brought a touch of Asia to a captivated bush audience and excerpts from Gary Lang’s Darwin Festival hit Goose Lagoon added a contemporary flavour to the program. The Bunggul—the traditional Indigenous performances that are part of any Top End Festival on Country—was led by the Groote Eylandt Dancers and Band. Displaying a great capacity for invention, these Groote Eylandt songmen were backed up by a rock’n’roll outfit with electric guitar, which added a foot-tapping beat to their mesmerising droning tones. They were definitely a crowd favourite, followed closely by the contemporary New Zealand ‘Maori Poi’ dance, which was taught and led by a local Maori teacher at the Jabiru Area School and performed with luminous ‘pois.’

Adding further spice to the multicultural mix was a Congolese dance troupe that appeared later in the program: such a confluence of cultures and influences has never been seen in Jabiru.

Techy Masero, Connor Fox and collaborators, Mahbilil Festival

photo Dominic O’Brien

Techy Masero, Connor Fox and collaborators, Mahbilil Festival

For all of this action and activity, the artistic highlight of the Mahbilil Festival was not by the lake but on it: a stunning installation of three giant traditional Indigenous figures, surrounded by giant floating lotus flowers, that stood sentry over the proceedings. Created by Darwin artist Techy Masero and a group of Territory artists who regularly work in Jabiru, the sculptures represented yawk yawks—the half-human half-fish mythological creatures, which, according to Indigenous cosmology, inhabit waterholes around the Top End.

Further artistic innovation was to be seen in the giant ‘turtle’ installation that formed part of the children’s parade. The turtle was both a canvas for a sequence of beautiful media projections and an interactive ‘set’ for the children of Jabiru, who emerged from the turtle’s mouth at twilight.

Mahbilil came to a close at midnight, with the rocking sounds of the Sunrize Band from Maningrida. The promise of something for everyone was met: this was an event that one could wander into and around at leisure, dipping into events and activities here and there, or, alternatively, settling onto a picnic blanket to watch the parade pass by—clowns, puppeteers and stilt walkers weaving their way through the crowd.

Staging any event in a remote area is a challenge, to say the least. And in Jabiru, which is a mining town, a regional hub, a gateway to a national park, there are entirely different ‘types’ if you like, living lives that never intersect. Yet with Mahbilil, Saint-Claire—a Darwin-based arts worker with extensive experience in remote Northern Territory communities—and his team have succeeded in bringing the community together for 12 hours by the shores of their manmade lake.

This is the strength of community arts. This is why, in this age of instant entertainment and constant distraction, they survive. Indeed Festivals on Country in the remote Northern Territory are thriving: they’re a live, visceral, dusty counterpoint to cyberspace, and combine contemporary culture with traditions and customs stretching back thousands of years.

As a relatively young venture, Mahbilil is still finding its way. It is certainly a festival to watch. The strong arts component—particularly the twilight art installations—set it apart from other regional festivals and has great potential to develop even further. With the strong support of the people, artists and sponsors, the festival looks set to become a feature of the Top End’s already flourishing Dry Season Calendar.

Mahbilil Festival, Jabiru Lake, Jabiru, Northern Territory, Sept 11

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. web

© Jane Hampson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Richard Hilliar, Hybrid Dream

photo Grant Stewart

Richard Hilliar, Hybrid Dream

IN HYBRID DREAM, ECLECTIVE PRODUCTIONS, A GROUP OF ARTISTS WHO HAVE LARGELY EMERGED FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND, ARMIDALE (NSW), CREATE A KIND OF DELIRIUM BY SEATING THE AUDIENCE IN THE CENTRE OF THE SPACE AND ENCIRCLING IT WITH PROJECTED IMAGES, SOUND AND PERFORMANCE IN A WORK ABOUT DREAM AND RELATED STATES.

Further unease is generated when single characters appear to be embodied by two performers at opposite sides of the space or two speakers at microphones face each other, intoning texts. The ensemble gathers, walks unexpectedly backwards in a circle, finally falling. Performers watch themselves projected onto screens around the space, the images slice up horizontally—nothing is stable. A man chalks “Nowhere” on a black wall. There are bursts of panic: we hear of someone stuck on the edge of a well: “I have no arms!” One performer chats to us about sleep: “Your imagination is at its strongest when you’re not even aware of it.” We hear of a woman who recalls an accident where she was badly hurt, but her serene version doesn’t include the screams that others heard. A performer watches a projected image of herself, shrieks and runs from it.

Projections in various degrees of close-up reveal a tasteful striptease act with feathers, danced to a woozy, gliding trumpet. Little flesh is revealed—it’s a classic tease—but meanwhile, in the dark on the mezzanine above us, the audience gradually becomes aware of a woman (the same one?) removing her clothes without any artistry until naked.

Hybrid Dream was an intriguing if sometimes infuriating experience: images were unnecessarily sustained, the work’s structure was opaque, some acting was over-the-top and performance and movement skills were uneven. However, the work’s stark evocation of dream states and parallel universes was generated with bracing fervour by a committed ensemble supported by a seriously sombre score ably delivered by a trio of musicians and a sound artist. It’ll be interesting to see where Eclective Productions take us next.

Eclective Productions, Hybrid Dream, creators, designers, directors Rachel Chant, Alanna Proud, performers Imogen Dodwell, Jonny Dutaillis, Lizzie Gibney, Richard Hilliar, Ben Horsley, Rhia Parker, Alanna Proud, Tristan Randall, Joanne Villacruz, sound designer Joseph Dutaillis, new media Grant Stewart, lighting Jamie Exworth; PACT Theatre, Sydney, Aug 11-15; www.eclectiveproductions.com

RealTime issue #99 Oct-Nov 2010 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

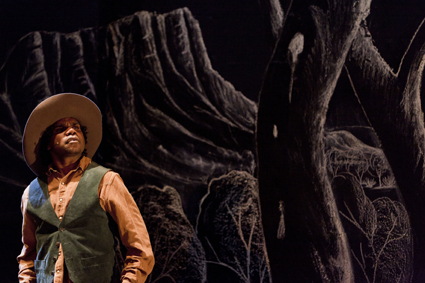

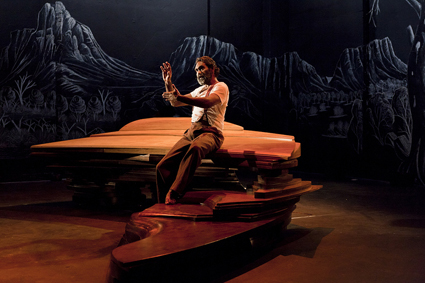

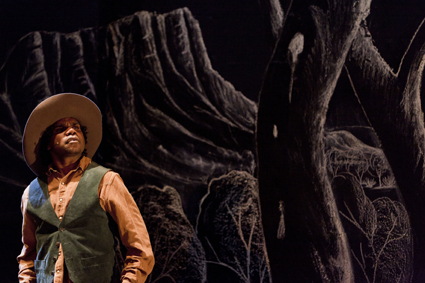

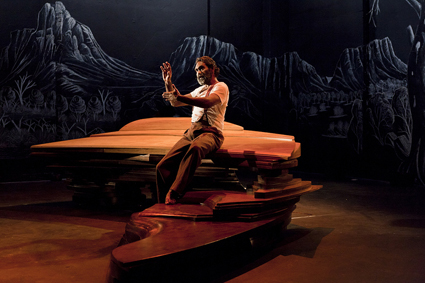

I HAVE NEVER SEEN THE MACDONNELL RANGES BUT TONIGHT THEY APPEAR BEFORE ME AS IF BY MAGIC. UPSTAGE, THE TWO BACK WALLS OF BELVOIR’S CORNER STAGE HAVE BEEN PAINTED BLACK AND COVERED WITH AN ENORMOUS WHITE CHALK MURAL DEPICTING THE RANGES AND THE GHOST GUMS THAT SURROUND THEM. WE ARE IN WESTERN ARANDA COUNTRY, THE HOME OF BOTH ALBERT AND KEVIN NAMATJIRA. THE FORMER IS THE FAMOUS WATERCOLOURIST WHO IS THE SUBJECT OF TONIGHT’S PERFORMANCE; THE LATTER IS HIS GRANDSON, AND AN ARTIST IN HIS OWN RIGHT, WHO IS ACTUALLY PRESENT, WORKING AWAY ON THE TEMPORARY WALL PAINTING FOR THE DURATION OF THE SHOW.

In front of these ghostly mountains, in the middle of the stage, is a large structure made of laminated wood that looks simultaneously like a deconstructed piano, an amorphous piece of public art and a section of undulating sandstone. Downstage is Trevor Jamieson, perched on a stool as the artist Robert Hannaford paints his portrait. The portrait looks well advanced but earlier production photos (see right) indicate that Hannaford started with a blank canvas, and like Kevin Namatjira, has been slowly adding to it each night.

Jamieson begins by introducing himself and his collaborators before sliding off his stool and telling the two seemingly unrelated stories of Albert Namatjira and Rex Battarbee. Namatjira was born as Elea but christened Albert by the Lutherans at Hermannsberg, where he stayed until he was in his early teens, at which point he returned to Arrernte country with his parents. Then at 18 he met and married his wife Rubina. Co-directors Scott Rankin and Wayne Blair throw the switch to vaudeville for this episode, with Jamieson as Albert and Derek Lynch as Rubina shimmying around the stage to Barry White’s “Can’t Get Enough of Your Love.”

Derek Lynch, Namatjira, photo Brett Boardman

This first story is intercut with a second: that of Rex Battarbee, a whitefella who grew up in Warrnambool until he enlisted to fight in the First World War. While away he saw England and France before being seriously injured and returning home. Towards the end of the act, Namatjira and Battarbee meet and become friends, with Albert showing Rex his country, and Rex showing Albert his watercolours.

In the second act, the story gains momentum, just as Namatjira’s life did, and we move briskly through his many successes: his first exhibition (1938); his entry into the Who’s Who (1944); the award of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation medal (1953); his meeting with the Queen herself (1954); and his attainment of citizenship (1957, a full 10 years before the referendum). However, success is bittersweet. Having money means that he has to support an extended family that numbers nearly 600 and having citizenship means that he has access to alcohol, which he is expected to share. When a woman dies on his property, it is he who is prosecuted because he is the only ‘citizen’ present. Namatjira is sentenced to six months hard labour, but after a public outcry is permitted to serve out the sentence at Papunya, where he eventually suffers a heart attack in 1959. The play finishes with his burial, and as we watch the man who has played him and the man who is descended from him stand in silence, it is as if we are witness to a second burial—the ghost of Namatjira is laid to rest in front of the ghostly mountains his grandson has conjured.

Trevor Jamieson, Namatjira, photo Brett Boardman

Beyond the impressive set (Genevieve Dugard), the principal pleasure of Namatjira is in watching Jamieson’s charismatic performance, as he slips between stories and characters, comedy and tragedy. Derek Lynch’s many sashaying women (black, white and a Queen to boot) are also enjoyable and Genevieve Lacey’s soundscape all-enveloping. The only false note in the evening comes after the curtain call when a stage manager reveals a small screen and we watch footage of the Big hART team working in the community. Presumably this is meant to reassure the audience about the nature of their engagement but it reads as both an odd sort of ‘reveal’ (and now, here are the real people) and as a pre-emptive strike against possible criticisms—one the production does not need since it is clear from both the program and the production itself that there has been not only consultation but also collaboration.

In a sense this collaboration echoes that of Namatjira and Battarbee, who apparently used to sit around in the evenings, talking about art, language and the world; two highly, if unconventionally, educated men, both of them globalised subjects before the word ‘globalisation’ even existed. This companionable image could serve as an analogy for the performance itself, for Namatjira is a convivial and thought-provoking night of stories, conversations and reflections.

–

Big hART and Company B Belvoir, Namatjira, writer Scott Rankin, co-directors Scott Rankin and Wayne Blair, creative producer Sophia Marinos, community producers Sia Cox, Pru Gell, performers Trevor Jamieson, Derek Lynch, artists Robert Hannaford, Kevin Namatjira, Evert Ploeg, Elton Wirri, musicians Nicole Forsyth, Genevieve Lacey, set designer Genevieve Dugard, costume designer Tess Schofield, composer and music director Genevieve Lacey, lighting designer Nigel Levings, sound designer Jim Atkins; Belvoir Street Theatre, Sept 25-Nov 7; www.namatjira.bighart.org/

Namatjira will tour to Melbourne, Dandenong, Geelong, Canberra and Illawarra from August 12 to September 30 2011. There are also plans for a national regional tour in 2012.

This article was first published online, Oct 12, 2010.

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 33

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

–

Top image credit: Trevor Jamieson, Robert Hannaford, Namatjira, photo Brett Boardman

Bloodbath, Bump Projects and the Sydney Roller Derby League

photo Jonathon Delacour

Bloodbath, Bump Projects and the Sydney Roller Derby League

TEAMS OF GIRLS ROLLER-SKATE AROUND A TRACK BENEATH THE LIGHTING RIG. THEY’RE DRESSED IN LITTLE SHORTS, RIPPED FISHNETS AND CROP TOPS, THEIR TATTS, DYED HAIR AND MAKE-UP CREATING A MISH-MASH OF EVERY CONCEIVABLE SUBCULTURE—PUNK, GOTH, ROCKABILLY, METAL. THEY’RE ALSO PADDED, HELMETED AND GUARDED TO THE GILLS. THEY SKATE FAST AND HARD; THEY’RE AGGRESSIVE SHOW-WOMEN, EGGING US ON WITH SUDDEN RUSHES OFFTRACK, KNEE-SKIDDING FLAMBOYANTLY TO STOP JUST METRES BEFORE THE ‘SUICIDE SEATING.’ THEY’RE LIKE THE TOUGHEST CHICKS YOU EVER CAME ACROSS IN SUBURBIA WHO YOU WANTED TO HANG WITH OR ELSE WERE SCARED OF. AND THE REAL GAME HASN’T EVEN BEGUN.

Roller Derby is an American sports entertainment currently enjoying a global revival, with roots going back through various forms of contact sport and competitive skating to Depression era games that gave poor women an outlet. Contemporary derby is mostly female and driven by a DIY ethos. Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion is routinely booked out by a crowd that ranges from westie families to inner-city dykes. Australians seem born to it— feral, ironic, in your face, and underneath the piss-take, bloody serious about their sport.

It’s the perfect theatre for Bump Projects, a formidable team of some of the best new media artists in the country—Linda Dement, Francesca da Rimini, Kate Richards, Nancy Mauro-Flude and Sarah Waterson—who in collaboration with Sydney Roller Derby League presented Bloodbath, a mediation of bodies through technology. The artists created a system to collect data from sensors placed on the skaters’ helmets, and in tonight’s game used this data to trigger works screened above the stage.

Bloodbath, Bump Projects and the Sydney Roller Derby League

photo Jonathon Delacour

Bloodbath, Bump Projects and the Sydney Roller Derby League

This was where the first problem lay. The smallish screens lined up side by side above the stage made for somewhat static viewing. The context is gladiatorial, in the round, but the screens stilled the gaze and crowded one another somewhat. Bigger and placed at intervals around the track, they would have integrated better with the action, a friendly bout between The Pistola Cholas and The Smackdown Sallies. (Yes, the team names, in keeping with the overall style, are facetious, OTT kitsch. Don’t get me started on the players’ names.) A quick look at the website indicates Bump themselves may have preferred a more spacious screen arrangement.

In this way the diversity of the works would also have been better appreciated. Dement’s, for me the most successful, was a bruise whose slow formation seemed a radical contrast to the mayhem of the track. But this clear articulation of trauma was apposite, the bruise healing to neutral skin, finishing with a lightly drawn flower or triggered by a collision to form another bruise immediately. Adjacent to Dement, Mauro-Flude’s text feeds were unfortunately barely legible to us in the bleachers opposite. The idea is interesting though: quotes from skaters, audience and artists, fed across the screen in a status update frenzy.

Kate Richards’ work, like Dement’s, seemed to survive the technical hitches best, her material being archives of old games. The alternately gliding or stertorous movements of the footage, colours becoming more intense with increased impact, complemented and grounded the event. As popular as the game is now, few of us have context for it, and this work went some way to providing it.

Bloodbath, Bump Projects and the Sydney Roller Derby League

photo Jonathon Delacour

Bloodbath, Bump Projects and the Sydney Roller Derby League

Da Rimini’s rich amalgam of medieval imagery, poetic fragments and mythical references felt too allusory for the context, but it has stayed with me. Waterson’s pink guitar, activated by the ramming blockers to play chords from Joan Jett’s “I Love Rock’n’Roll,” couldn’t be heard until towards the end and the visual was so subtle the whole thing didn’t appear to be working for much of the night.

Due to the many technical problems beyond the artists’ control, I felt I was attending a scratch version of Bloodbath, so my criticisms are reluctant. What could emerge from this project is incredibly exciting. If the works were to be fully integrated, they could become intrinsic. Roller Derby has a quasi-futuristic feel, partly because it’s women out there engaging in the sanctioned violence that draws us to sport. At the same time it’s the most ancient form of theatre, something that Francesca da Rimini is pointing to. The medium and method are attuned to the game, it’s just a question of the artists being given all they need for their works to be fully realised.

The second match of the night, Sydney’s Assassins vs Canberra’s Vice City Rollers, was a corker. Sydney led for much of the first half, then Canberra surged and it was neck and neck until a three point win by Sydney scored in the very last minute.

Bump Projects and the Sydney Roller Derby League, Bloodbath, artists Linda Dement, Nancy Mauro-Flude, Kate Richards, Francesca da Rimini, Sarah Waterson, producers Linda Dement, Kate Richards, original concept Linda Dement, technical development Mr Snow, House of Laudanum; Hordern Pavilion, Oct 9; http://bumpp.net/

This article was first published online, Oct 25, 2010.

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 22

© Fiona McGregor; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Next of Kin, Restless Dance Theatre

photo Chris Herzfeld

Next of Kin, Restless Dance Theatre

restless relatives

Restless Dance Theatre is typically described as a youth dance company that works with dancers of mixed abilities (see our reviews of Bedroom Dancing and Safe From Harm). However, in their latest show Next of Kin, they will be working with dancers of mixed ages as well. Next of Kin has an intergenerational cast of six to 60 year olds (some of whom are related in real life) and, according to the press release, “focuses on the family unit and its complex effect on kin relationships, personal decisions and individual responsibilities.” The show features a set designed by award-wining designer Gaelle Mellis and music by Zephyr Quartet’s Hilary Kleinig. The show also marks the directorial debut for Philip Channells, the company’s new artistic director. Restless Dance Theatre, Next of Kin, The Opera Studio, State Opera of South Australia, 216 Marion Road, Netley SA 5037, Nov 12-20; http://restlessdance.org/

physical music

Ensemble Offspring, who describe themselves as “champions of innovative new music” (previously reviewed in RT99 and RT92), are collaborating with one of Sydney’s most engaging performers, Katia Molino, and director Carlos Gomes of Theatre Kantaka, in a one-off event that is “as much physical as it is musical” (press release). The show, called Sounds Absurd promises to investigate “the visual spectacle surrounding the live performance of music” and will include “dancing hands, body slaps and musical instruments in nooses and upside-down cellos in drag” (press release). The evening will feature the music of Mauricio Kagel, a world premiere from Australian composer Moya Henderson, along with works by Thierry de Mey, Vinko Globokar, Matthew Shlomowitz, Stephen Stanfield and Jude Weirmeir. Ensemble Offspring, Sounds Absurd, CarriageWorks, Nov 30; www.carriageworks.com.au

musing and commuting

If you’re in Melbourne this month and, more specifically, passing through Southern Cross Station, keep an eye out for a studio, tea station and lounge. Set up by the artist collective one step at a time like this (formerly bettybooke), this installation is part of a project called Southern Crossings. Commuters will be invited to visit the group of artists at the station and contribute their stories about who they are, what they are doing and where they are going. Drawing on elements of their previous project en route (praised by Jana Perkovic in RT94), these stories will then be integrated into Southern Crossings, an audio journey on iPod which guides audience members through the station. “[I]ndividuals have an opportunity to see and experience the railway station beyond its everyday use—to think about people and places—and to engage with an iconic landmark from a different and more personal perspective” (press release). one step at a time like this, Southern Crossings, Southern Cross Station, stories collected Oct 25-Nov 16, showings Nov 18-Nov 28; www.onestepatatimelikethis.com/

Suspended Motion

photo Pilar Mata Dupont

Suspended Motion

skaters in suspense

Over in Perth a similarly interdisciplinary project is underway at the Breadbox Gallery. Suspended Motion, features five artists—Ben Baretto, Cameron Campbell, Jason Hansma, James Hensby, and Tom Muller. Working with a team of builders and “skateboarding creatives,” including professional skateboarder Morgan Campbell, the artists will take over the Bakery to create sculptural installations, video and images where skateboarding will be used as a creative medium. You can see the video trailer here and read Darren Jorgenson’s review in our November 22 online edition. Suspended Motion, curator James Hensby, the Bakery, Breadbox Gallery, Oct 23-Nov 4; www.nowbaking.com.au

Dawn Albinger, No Door On Her Mouth – A Lyrical Amputation

photo Lisa Businovski

Dawn Albinger, No Door On Her Mouth – A Lyrical Amputation

shut your trap

Perth is also the place where writer/performer Dawn Albinger will be premiering her intimate new solo No Door On Her Mouth – A Lyrical Amputation. Using her signature tragic-comic style, she deploys fragmented narrative, poetic text and subtle humour to dislodge dominant readings of ‘romance,’ ‘femininity’ and ‘desire.’ Invoking choking divas, handless maidens and flightless women, the performance (with dramaturgy by Margaret Cameron and video art by Samuel James) offers “a philosophical answer, and performative response, to Irigaray’s question of how to say ‘I love you’ without it meaning ‘I wonder if I am loved’” (press release). Albinger’s Heroin(e) was reviewed in RT88) and this show will be reviewed in RealTime 100. Dawn Albinger, No Door On Her Mouth – A Lyrical Amputation, Blue Room Theatre, Oct 26-No 13; www.blueroom.org.au

light up, light up