Australian

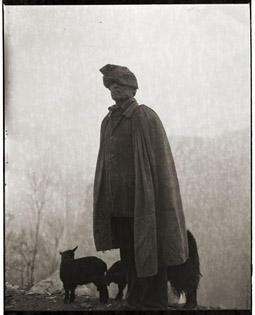

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

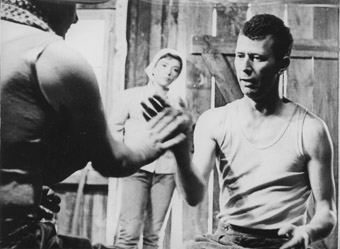

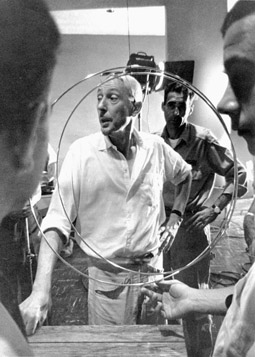

Joel Edgerton, Cate Blanchett, A Streetcar Named Desire, Sydney Theatre Company

photo Lisa Tomasetti

Joel Edgerton, Cate Blanchett, A Streetcar Named Desire, Sydney Theatre Company

a streetcar named desire

It was with some apprehension that I went to see the Sydney Theatre Company’s A Streetcar Named Desire. First, would Cate Blanchett be too young and temperamentally too strong to realise Blanche DuBois’ fading beauty and emotional fragility? Secondly, did an actor as able and inventive as Blanchett need an exotic import like Liv Ullmann as her director? Or was the choice simply a signal of psychological seriousness and world’s best practice? Thirdly, the word was out that the production was going to be conventionally staged. What could we possibly learn from that?

I’d watched the opening scenes of Charlie Kaufman’s film Synecdoche, New York with amusement as a director (Philip Seymour Hoffman) daftly cast Arthur Miller’s The Death of a Salesman with a young Willie and Linda in an otherwise straightforward staging. I’d read Daniel Mendelsohn’s caustic account of Natasha Richardson’s 2005 performance as Blanche in New York with “the sexless glow of an Amazon, or given her coloring, perhaps a Valkyrie” (“Victims on Broadway II”, How Beautiful It Is and How Easily It Can Be Broken, Harper Perennial, 2009). In trying to up the gender wars ante in the Blanche-Stanley conflict Richardson and her director, Mendelsohn complains, had reduced the woman’s vulnerability and altogether eliminated the potential for sexual frisson between the protagonists—a key element of the play for him and so evident in the Elia Kazan film with Vivienne Leigh and Marlon Brando.

At one level, I needn’t have worried about Blanchett. Once again, her capacity for transformation was evident in the overall conception of the role and in myriad details. Her Blanche is driven by a nervous energy that is always on the edge of exhaustion: a quivering alertness alternating with distracted inwardness. Bursts of posturing, over-confident lying and angry self-defense increasingly weary her until, fractured, confession and withdrawal ensue. This stripping away of the Southern belle facade is amplified by the ‘undressing’ of Blanche. Ullmann and Blanchett rightly make much of Blanche’s relationship with her clothes, in the end leaving her with even less dignity than we might expect—exiting abject in petticoat and bare feet. Another image, seen twice, that disturbingly complements this descent has Blanche, still and silent, squatting on the floor with a piece of cloth draped over her head, cutting out a world she can no longer handle. Perhaps it’s this imagery that Liv Ullmann, with her experience of the film world of Ingmar Bergman, brings to Blanchett’s interpretation of Blanche—a complete psychological demolition of the woman and concomitant physical weakening.

Joel Edgerton’s Stanley in the opening performance didn’t seem interpretively distinctive but looked right and by the second half the rolling momentum of his psychological and physical assault on Blanche, and its roots in her overheard reference to him as an ape, is fully felt. As for any sexual play between this Blanche and Stanley, I didn’t detect it, and the rape was a rape. This might not satisfy Daniel Mendelsohn should he see the production when it bravely tours to New York. Blanche and Stanley here are simply antagonists, the complexity of the production residing in the woman’s condition. Certainly there’s no concealing the danger that Stanley embodies—a capacity for blind physical violence, against men as well as women—and a community that hypocritically abides it and for which Blanche is sacrificial victim.

Blanchett’s performance is admirable, above all, for conveying a palpable sense of Blanche’s suffering and her limited self-awareness, but I was left wondering what could have been revealed by a more inquiring director. Ullman’s production looks like one that could have originated on Broadway at any time since the play’s premiere. On the positive side there’s the fidelity to Tennessee Williams’ very particular sense of light and sound in Nick Schlieper’s lighting, sharply contrasting the moonlight and dark in which Blanche hides with, for example, sunlight blazing through a window, while Paul Charlier and Alan John do film score justice to the writer’s desire for a sound world which includes music largely heard only by Blanche, and ourselves. The kind of ‘magical realism’ that Williams was aiming to achieve is, then, partly realised if not forthcoming elsewhere.

The set design emphasises the limits of the production. Ralph Myers (whose wonderfully expressive designs for Benedict Andrews and Barrie Kosky sometimes evince an architectural sensibility, as in the thrusting rooms in Act 2 of Lost Echo) places atop of Stanley and Stella’s humble 1940s apartment a giant, oppressive block of 50s modernist construction that fills the upward balance of the stage, as if perhaps to highlight a world that has moved coolly on from these downstairs melodramatics. However, the apartment setting itself looks not simply like a poor American home but a standard American stage set. As well, there’s an uncomfortable feeling of facing a pronounced fourth wall, of peering into rather than sharing a world (amplified if you’re some distance from the stage) where the actors, for the most part, play to each other across the stage in a self-contained world. This is at a time when stage acting is in a fascinating period of transformation with much gestural and spatial play and a return to, or radicalising, of older conventions of performance in more direct relation to the audience.

If grateful to have witnessed Blanchett’s performance, not least in the final stages of Blanche’s decline, the residue of feeling about the production was of over-familarity, of museum mustiness that blunted the threat that A Streetcar Named Desire can still doubtless deliver. We are quietly reminded of this not in the passages of high passion but when Blanche is tempted to seduce the boy collecting newspaper money or the silent moments when she covers her head.

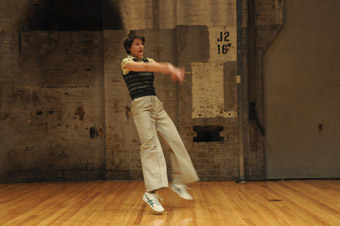

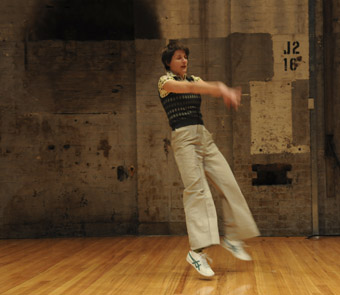

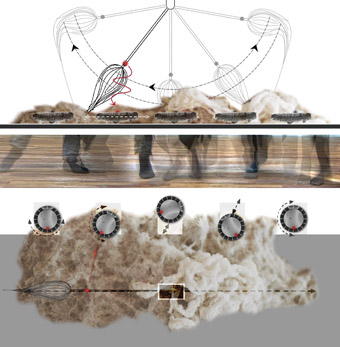

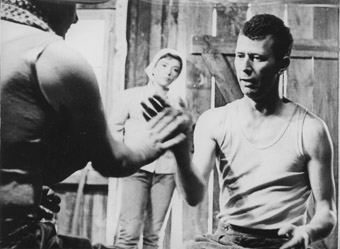

Kim Vercoe, David Williams, This Kind of Ruckus, version 1.0

photo Heidrun Löhr

Kim Vercoe, David Williams, This Kind of Ruckus, version 1.0

this kind of ruckus

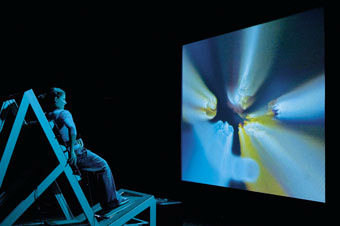

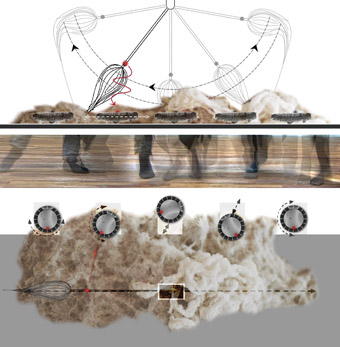

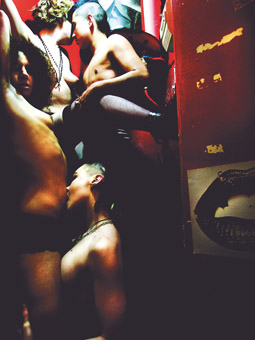

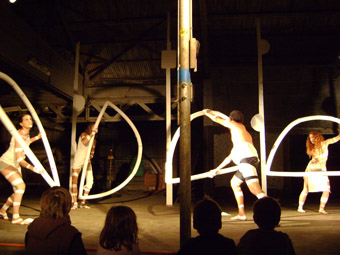

It’s a quick trip across town, from Tennesee William’s 1947 at Sydney Theatre to version 1.0’s 2009 at CarriageWorks, but not a lot has changed—the violence perpetrated by men against women is still the issue, but the way of playing it is light years away. Version 1.0’s mixed media and performance modes have cast a widely admired ironic and revealing light on contemporary politics, but in This Kind of Ruckus the company inhabit a reverie confabulated from their own raw materials instead of their customary drawing on government reports, Hansard and the media.

The outcome is a large scale looping reverie of motifs, strange tales, fragmented encounters, unlikely cause and effect, missing links and a dense layering of metaphors. There’s little that’s literal. The outcome is a work of peculiar beauty, like a half-remembered dream, part-nightmare, replete with oddly aestheticised violence and not a little humour. “It was funny, in an ugly kind of way”, I heard someone say.

This Kind of Ruckus is like a Freudian dream theatre: images repeat, split, multiply, condense, mirror themselves; figures appear in new guises; narratives fragment, skip beats; episodes re-play with new variations, some obvious, some distant. Suspended screens appear to duplicate the live action below, but are as likely to contradict stage conflict with images of fond intimacies. The screens reveal memories of distress and trauma but also images of wish fulfilment.

The performing space itself transforms, multiplying meanings. Initially a huge curtain, lit red, looms over the audience with the cast lining up as cheer leaders, locked into position, ready for the “1, 2, 3…” Instead they abruptly sit and chat, one vigorously telling a story of two women on a Saturday night drive witnessing city street violence and fantasising vigilante action on behalf of endangered females—until they’re disabused by a sinister policeman. The storyteller is joined by another of the cheerleaders and together they ogle the men in the audience, making lewd offers. Actually, they’re mimicking male behaviour; a dismissive male cheerleader states the obvious: “You haven’t got the balls.” The curtain is gone, revealing a wall and floor of quilted bubble wrap, suggestive of a padded cell or, a dance club, a therapeutic space. Above is the screen, to either side, tables with rows of alcoholic drinks which the performers consume regularly with an escalating sense of bingeing, especially by the women.

The opening scene is indicative of the metaphorical layering and shifting which are the show’s modus operandi: the image of an unspecified sporting function mutates into a storytelling bout, into some calculately confusing gender role shifts, and then morphs into a “this is theatre” mode and offers an ambiguous performing space in which a seated man stares at a woman sprawled on the floor, possibly unconscious, perhaps lifeless. A victim of violence?

Before the curtain closes when the cheerleaders return for their oranges at half time, the audience has had printed into its consciousness a series of images and episodes. Central to these is the man watching the woman on the floor. We’ll see the same couple in conflict but intimate on the screen, and then undergoing counselling in this padded room. The counseller negotiates the man’s approach to the woman, constraining him according to the woman’s response (“He was pretending not to walk but he is walking. It’s a bit creepy.” “He feels tall, toweringly tall.”) She’s wounded, volatile. He’s accommodating, but has nowhere to go. Our empathies swing; we’re deprived of context.

In a parallel scene in the second half, when wall and floor have disappeared to make way for a large space down which the performers can hurtle as if in a race (sport again?), a man approaches a woman. An escalating, grating score suggests the location as a dance club. He draws very close, moves about her, touches her cheek, her arm. She does nothing. He touches her breast. She waits then briskly walks away. He shivers, rejected; he shakes with body-consuming fury. Elsewhere in the performance, the same figure has quietly repeated a few questions to a woman that suggest the controlling personality that underlies jealousy. We make the link. Later images are more overtly suggestive of violence: blood smeared across faces and torsos, male and female. The man who stared at the floored woman, now sits bloodied, naked to the waist, at the same angle, but now in the distance. We guess at the cause, the event has gone missing. Her blood or his? We guess, we weave.

In This Kind of Ruckus version 1.0 has studiously avoided making documentary theatre, instead conjuring suggestive images of the triggers for and aftermaths of male violence against women. Some of these are blunt and a few surprisingly literal (a court scene in which a victim’s humilation is intensified by a female defense council). Most are more complex, ambiguous even. Likewise, the framework for the show appears to be rooted in sport, but it’s cheerleaders we see, not players, in an unglamorous rendering of a mere fragment of the spectacle.

Once sport was thought of as a means for sublimating sexual desire but we see it now as locus for sex, violence and corruption. This Kind of Ruckus might have been ‘inspired’ by a spate of sports-related sexual violence but it’s not an investigation of that phenomenon—which has included the desire of team members to witness each other having sex with the same woman in the same room at the same time. This show essentially operates at a more atomistic level—the couple. The second half, for example, opens with the story of a woman terrified into having sex with her partner after she’s told him the relationship is over. The following morning they have breakfast as if nothing has happened and she never sees him again. The other members of the cheer squad quietly imply she triggered his threatened violence, as does the defense lawyer later on.

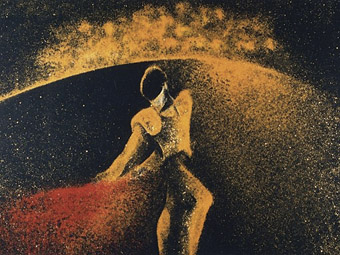

Other than sport, it’s dancing—noisy, ruckus-y, lewd, limp and falling-down—and alcohol consumption that provide a mutating framework for the show’s sexual violence, not as causes per se but amplificatory, suggestive of an inescapable loop of the forces at work in the nightmarish arena that version 1.0 has created. With its distorting single figures, blurred couple action (sometimes glimpsed through bubble wrap), spare scenography and projected video diptyches, This Kind of Ruckus recalls the febrile visions of Francis Bacon.

The company, with guest Arky Michael, performs with great no-frills conviction and ever intensifying ensemble strength while Gail Priest’s dense, pulsing score (breaking glass and riot melded with dance beats) and Sean Bacon’s haunting live and pre-recorded projections provide motifs that not only heighten the show’s dream sense but anchor its wilder flights.

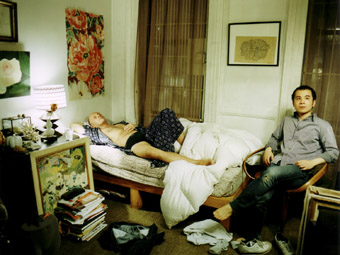

Barbara Spitz, Florian Carove, Poppea

image courtesy Sydney Opera House

Barbara Spitz, Florian Carove, Poppea

barrie kosky’s poppea

If you love Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea (1642) you have to put much of it out of mind to enjoy Barrie Kosky’s re-working of the opera as vigorously entertaining, comic to the point of silly, sometimes aptly repulsive music theatre. All opera is music theatre but not all music theatre is opera. ‘Theatre’ is writ large in this production. It’s not that the music is secondary in any way, but rather that its realisation is infinitely more theatrical than even the most progressive of 21st century opera productions (even New York’s Metropolitan Opera, in search of new audiences, has mounted a new Tosca set in an industrial warehouse and replete with blow job for Scarpia). This Poppea has been created for and is rooted in the theatrical capacities of performers Kosky worked with in Vienna and even where they are stretched by the music (Cole Porter no less a challenge than Monteverdi) they bring it into their own range, entirely in character. Beatrice Frey as a tall, Shelly Duvall-ish Octavia ascends in falsetto to the top note, reaching it with a cracked screech—funny, without any sense of parody and apt for the empress’ frustrations.

Elsewhere Kosky redistributes musical passages to pointed psychological effect. Seneca (Florian Carove), the playwright-philosopher adviser to Nero (Kyrre Kvam), is played as mute, his tongue having been torn out as prelude to a forced sucide. Nero, hovering over a bloodied Seneca awash with blood in a bath tub, sings his erstwhile tutor’s lines as if knowing precisely what he would argue. It lends Nero a sharper intelligence, intensifying the sense of danger he embodies along with the ambivalent feelings as he embraces and then bluntly tosses aside Seneca’s body. Fittingly, Kvam’s singing is the closest to operatic.

The physically sexual intensity of the production is evident early on when the erotic play between Nero and Poppea (Melita Jurisic) has the emperor behind his mistress, his hands tightening around her neck in an act of sexual strangulation, grimly counterpointing opera’s breath-based, orgasmic soaring. Later there’s cunnilingus (to “Anything Goes”), Nero briskly rapes Ottone (Martin Niedermair as Poppea’s former lover) and Poppea cuts Nero’s chest. The emperor’s court is joyously and dangerously decadent, making actual what was only suggested in the opera.

Ottone, quite unlike the furiously angry man in the Monteverdi, is played here as a love lorne, lugubrious intoner of Cole Porter songs while looking like a sailor refugee from Fassbinder’s Querelle de Brest. He plots with Nero’s wife, Octavia, to kill Poppea with the help of the latter’s servant, Drusilla (Ruth Brauer-Kvam)—now infatuated with Ottone. An exotic, Theda Bara-ish presence in the court, her vocals inflected with a husky Eastern-European twang, Jurisic’s Poppea is sensual, self-possessed and single minded in her ambition, but the physical centre of the production is Drusilla, a joyful dynamo whose dancerly speed and contortions recall Meow Meow at her most excessive. Amor (Barbara Spitz), the god of love, on the other hand is a languorous observer, a droll queen, not the cute devil-cupid of some 20th century productions.

The final duet, shared by both the opera and this music theatre confection—when the emperor has, remarkably, forgiven and banished the plotters—is as affecting as ever. Poppea’s dark mezzo underlines and entwines with Nero’s lilting tenor. Love has unexpectedly weathered the rampages of lust and perversion even in Kosky’s grimly hysterical 21st century rendering. Compared with The Lost Echo and The Women of Troy, Poppea is Kosky-lite and his idiom now more than familar if never less than fascinating—especially as realised by such formidable performers.

the rameau project

While Barrie Kosky preserves the essential narrative of Monteverdi’s opera, the principal characters and some of the music, Nigel Kellaway’s approach to classics of any kind is very different and, in Rameau, more demanding if you’re not familiar with the source material. He has high expectations of his audience. In a season of three free performances in one of the voluminous CarriageWorks tracks, The opera Project presented a new music theatre work after the 18th French composer with whom Kellaway feels a particular affinity.

The centre of this work was not a Rameau opera (these have recently found new favour in major productions in Europe) but Genet’s play The Maids supplemented by texts from other sources and a strand of petulant satire that had Kellaway on the phone to Cate Blanchett negotiating an unlikely collaboration. The text-based scenes were punctuated by pieces largely from Rameau cantatas scored by Kellaway for two violins, two cellos, double bass, piano and singer Annette Tesoriero, who doubled as the maids’ Madame, voice-off and elegantly fulfilled a range other functions. The small ensemble was particularly effective, neither emulating a period feel nor, thankfully, sounding like a 19th century chamber group. Tesoriero’s lucid singing made the Rameau a double pleasure. As for what the songs were about…none of the luxury of Opera House surtitles here.

Compared with previous opera Project productions Rameau was efficient, a meticulous, upgraded work-in-progress showing, no mean achievement given the late replacement of Regina Heilmann (called away on a family matter) by Nikki Heywood with script in hand. Over a number of productions, Kellaway and Heilmann have developed a mutual playing idiom, somewhat Brechtian, intoned, almost dancerly and most memorable in their take on George and Martha from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf in The opera Project’s Another Night: Medea, 2003 (which drew in part on Clerambault’s cantata Medee, 1710). Passion in this manner of playing is palpable, but tautly framed, indeed operatic. Heywood broke the mold, countering the arch, strutting imperiousness of Kellaway’s maid with nuanced responses and a felt emotional collapse, at the same time avoiding conventional psychological realism. Kellaway’s maid departed like a strangled diva, deprived of her aria.

Rameau confirms Kellaway’s esoteric vision—musically scholarly, literary, in love with the cut and paste of building idiosyncratic works out of others’ classics. It’s a modus operandi he shares, broadly, with Kosky, and one which faces the inevitability of likewise becoming itself ‘classical.’

the duel

With the Elevator Repair Service’s seven-hour ‘reading’ of Gatz still resonating pleasurably in mind and body, a visit to the ThinIce/Sydney Theatre Company production of The Duel (from an episode in Dostoevsky’s novel, The Brothers Karamazov) proved to be a bonus. Tom Wright’s adapation dextrously interweaves direct storytelling with adept dramatisation played out in designer Claude Marcos’ wide, shallow box of a room emblematic of the closed circuit of social relations and codes that one man will rupture, if only for his own moral salvation. Like postmodern dancers, the actors stand about, observing and then suddenly slipping in and out of storytelling or acting as required. Played very close to the audience, the performances are realised with an absorbing, intimate intensity by Luke Mullins, Renee McIntosh, David Lee Smith and Brian Lipson. Lutton’s directorial hand is assured. It would be good to see more of Perth’s ThinIce in this kind of welcome co-production in a period, at last, where more and more shows cross state borders as well as the boundaries of form.

the city

Benedict Andrews’ meticulously faithful account of Martin Crimp’s The City precisely captures the playwright’s ambiguous tone. Crimp appears to be the inheritor of the early Pinter idiom, not in his silences but in the signifiers that refuse be nailed down and the threats that come with their instability. Characters are constantly uncertain of the topic of conversation or their position within it and seek clarification—the apparent banter of social comedy quickly turning dark when characters can’t read intentions. Crimp calculatedly extends the resulting verbal ambiguities (about love, family, identity, war, vocation and storytelling) into physical reality when a small girl, the daughter of the principal characters, Clair and Chris, suddenly appears dressed identically to the nurse, Jenny, who is the family’s neighbour. At this stage, Clair, a translator and would-be novelist, suspects (as we do) that she might be inventing her own and her family’s reality.

Much more than a postmodern conceit, this scary bleed between worlds real and imagined runs through this short (80-minute) but remarkably dense work. The very notion of the city shifts about restlessly, one moment a cruelly adaptive market economy and uncomfortably cosmopolitan, the next a model of a writer’s inner world, elswhere the scene of war. The neighbour Jenny confides an account of a “secret” war (where her husband is a doctor): “the city has to be pulverised so that the boys—our boys—can safely go in and kill the people who are left—the people, I mean, still clinging to life.” Director and cast wisely eschew literally enacting the anxieties prompted by these uncertainties; the tone, not least in Belinda McClory’s finely idiosyncratic performance as Clair, is close to social comedy and all the more chilling for it. Characters are distracted, suprised and indifferent by turns, and like the verbal dancing, it’s hard to tell which way things are going, like Chris’ happy transformation from businessman to supermarket butcher.

Ralph Myers’ set almost looms over the audience, mirroring the seating rake in a series of giant carpeted steps (an abstracted city garden) requiring the performers to make their moves often with great effort, amplifying, if too awkwardly at times, the real challenges of meeting each other and negotiating already problematic communication.

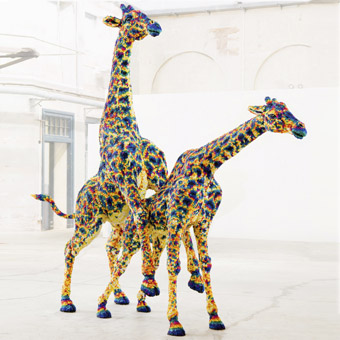

Lots in Space, UNSW/NIDA

photo courtesy NIDA

Lots in Space, UNSW/NIDA

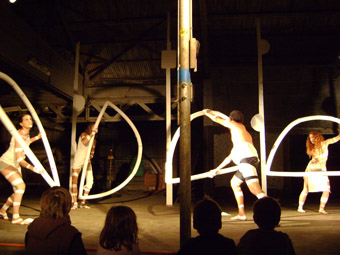

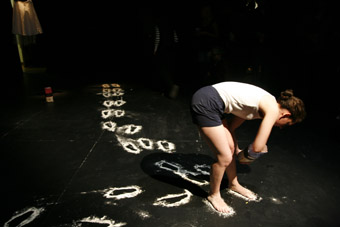

nida: lots in space

Melbourne director Peter King has been NIDA’s inaugural artist-in-residence for six months this year, bringing together first year actors, students from NIDA’s open program, the McDonald College of Performing, UNSW Performing Arts and the UNSW Faculty of the Built Environment to collectively create Lots in Space. The outcome was an engrossing epic, true to the director’s architectural passions, flowing from the Parade Theatre foyer up the UNSW Mall, moving from installation to installation, and back to the theatre for a performance.

On the mall we glimpsed, through glass, figures in a halting abstracted Renaissance dance descending the Law Library stairs. Further on virtual water tumbled spectacularly down a raked square on which actors played out an excerpt from Thomas Middleton’s Women Beware Women (c1621). Around a corner a huge moon and scrolling text filled a vast facade below which performers danced, then led us back down the mall, completing a circuit of some 10 installations. In the theatre, images from the promenade recurred alongside further excerpts from Middleton’s play, Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Pericles and, hugely projected, Eistenstein’s Ivan the Terrible.

The almost ritualistic ebb and flow of large numbers of performers was dotted with microcosmic moments of intense drama of manipulation, oppression and sudden release. If at times a bewildering collage (a treasure house for keen quotation identifiers and cross-referencers), Lots in Space displayed organisation, collaboration and commitment of a high order. The young actors were impressive and the promenade installations revealed a confident engagement with powerful projection technology. Lots in Space was an apt celebration of UNSW’s 60 years and NIDA’s 50, when it needs to be looking to the demands of a diversified performance sector in the 21st century.

–

Sydney Theatre Company (STC), A Streetcar Named Desire, writer Tennessee Williams, director Liv Ullmann, performers Cate Blanchett, Michael Denkha, Joel Edgerton, Elaine Hudson, Gertraud Ingeborg, Morgan David Jones, Russell Kiefel, Jason Klarwein, Mandy McElhinney, Robin McLeavy, Tim Richards, Sara Zwangobani, musician Alan John, set designer Ralph Myers,?costumes Tess Schofield, lighting Nick Schlieper, sound designer Paul Charlier; Sydney Theatre, Sept 5-Oct 17;

version 1.0, This Kind of Ruckus, performer-devisors David Williams, Danielle Antaki, Arky Michael, Jane Phegan, Kym Vercoe, video artist Sean Bacon, sound artist Gail Priest, lighting Neil Simpson, devisor-dramaturgs Deborah Pollard, Yana Taylor, Christopher Ryan; Performance Space, Carriageworks, Sept 3-12;

The opera Project, The Rameau Project, writer, director, composer Nigel Kellaway, performers Nigel Kellaway, Nikki Heywood, Annette Tesoriero, dramaturg Bryoni Trezise, lighting Simon Wise; Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Aug 20-22;

The Duel, adapted by Tom Wright from Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, director Matthew Lutton, performers Luke Mullins, Renee McIntosh, David Lee Smith and Brian Lipson, designer Claude Marcos, lighting Damien Cooper, sound design Kingsley Reeve; Wharf 2, STC, opened June 9;

The City, Martin Crimp, director Benedict Andrews, performers Georgia Bowrey, Anita Hegh, Belinda McClory, Colin Moody, Gigi Perry, set designer Ralph Myers, costumes Fiona Crombie,?lighting Nick Schlieper, composer Alan John; Wharf 2, STC, opened July 3;

NIDA and UNSW, Lots in Space, director Peter King, designers Matthew McCall, Kate Robert, Aron Dosiak, lighting Sarah Kenyon, Richard Whitehouse, UNSW Mall, Parade Theatre, Sydney, July 21

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg. 44-46

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

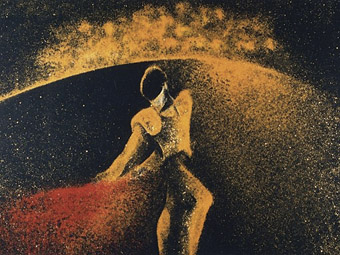

Lisa O’Neill, The Pineapple Queen

photo Sean Young

Lisa O’Neill, The Pineapple Queen

HOWEVER IDIOSYNCRATIC, LISA O’NEILL IS AN ICONIC QUEENSLAND DANCER, ACTOR AND NEW MEDIA ARTIST. WITH HER OWN DEEP SENSE OF IRONY, THE PINEAPPLE QUEEN MIGHT SEEM TO HAVE BEEN INTENDED TO SELF-REFLECT THIS CULT STATUS, AS INDEED IT DOES, BUT NOT IN A WAY PERHAPS MANY OF US EXPECTED.

the pineapple queen

This collaborative performance piece at the Roundhouse Theatre began as a more condensed, feral affair gleaned from a reworked script by writer Norman Price in 2004 as part of a series of Dada inspired performances around Brisbane. This piece and its developments, one says admiringly, exhibited O’Neill’s usual strengths. However, the La Boite showing added a new dimension of transparent vulnerability to O’Neill’s performance and repetoire. Strong dramaturgical input from director Ian Lawson elastically stretched definitions of both theatre and performance for La Boite who showed nerve in mounting this production.

The Pineapple Queen is presented through short scenes and minimal effects reminiscent of Buchner’s Woyzeck retold in a rural Queensland setting. The crucial elements in Buchner’s play—the dark pool (love and suicide) and the encroaching storm (Woyzeck’s madness)—are reproduced to similar effect in this production by the mysterious “coal hole” and the storm over the Glass House Mountains. However, as the Glass House District Pineapple Queen, it is O’Neill who is going mad, and her romantic self-confabulations and grand illusions are butresses against this end. As her defences crumble, the domestic brutality and squalor of the protagonist’s marriage are revealed in a final directorial coup which exposes O’Neill’s character as no longer capable of ‘acting.’ It is as if we are seeing Buchner’s Marie further down the track with her Sergeant, with all the nasty implications of history implacably repeating itself. In the final fadeout on the dethroned queen, cringing without any armour, it is as if we too have been effectively shut out from the text, along with her, denied a voice in history.

If the voice of history is patriarchal and monological, where are our vaginas? The central image of the hole in the Golden Circle Pineapple and the ellipses implied by the “coal hole” alert us to the gaps in consciousness, language and the body where real possibility for dialogue in this dark fairy tale exists. But Ian Lawson’s narrative uptake drives the play like a detective story, providing clues to the Queen’s madness, and this is indeed intriguing while ironically we are complicit from this monolithic vantage point in excluding her voice. But that a realistic explanation would ever be sufficient clue is moot given that the cause of her trauma is so shockingly and symbolically overdetermined in what is proposed in the final analysis—that she was forced as a child to assist her mother to self-abort with a baling hook, and that she herself repeats this familial cycle of violation. Her own comically depicted abortion of a pineapple after a vicious rape has an appropriately hallucinatory edge.

Despite such shocking imagery, this production sustained an uncanny poetic flow, all the elements contributing to maintaining a heightened feel that this woman is trying, above all, to survive and live. Price’s text this time is more spacious and allows the performance to move forward adeptly. Michael Coughlan, as the Pineapple Queen’s husband, delivers a superbly timed, immaculate performance of restrained emotion and potent physicality. The animations by Jaxcyn, projected onto the floor, such as the pineapple process plant at which The Pineapple Queen presumably worked in a menial position, or the expanding flower arrangement on which O’Neil danced, is simply the best integrated video design I’ve seen in a very long time. These were matched by David Walters’ subtle lighting and portentous music from Guy Webster.

There seem to be two versions of The Pineapple Queen. The earlier, more surreal version was easier to laugh at; the second is harder to watch, but equally rewarding in very different ways. In the first, The Pineapple Queen resorted to an axe to decentre authority or perhaps, more importantly, to perform a creative, purposeful act of self-authority. In this one, we see the performer Lisa O’Neill make a huge leap with the assistance of generous collaborators to lay herself open to dialogue with multiple voices.

Genevieve Trace, Kieran Law, Transverse Fracture of the First Metacarpal

photo Yvette Turnbull

Genevieve Trace, Kieran Law, Transverse Fracture of the First Metacarpal

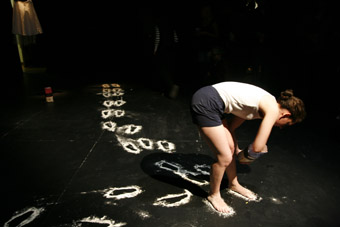

transverse fracture of the first metacarpal

Another work in the physical performance vein was Transverse Fracture of the First Metacarpal performed as part of the Independents 2009 season at the Sue Benner Theatre at Metro Arts. This often disarming but deceptively contrived piece dealt with personal encounters with physical injury and rehabilitation by the co-creators Kieran Law and Genevieve Trace. That this might be of major industrial concern for starting out artists was emphasised, coincidentally, by the fact that only relatively recently did mid-career artist Lisa O’Neill return to performance after significant time out due to injury. Curiously, the shows bear a resemblance.

Law and Trace warmly engage with the audience and each other, developing a neat patter between them and bearing lightly on their physical injuries. Trace is particularly funny as she clowns through the story of how she seriously hurt herself while in the original daffy costume she wore on stage as a teenage performer. Law plays a more bashful muggins when he describes the usual dumb things young men do that resulted in his own injuries, although, to be fair, Trace unrepentantly confesses to having her nose broken in a stupid fight with her sister.

There’s an underground tension that emerges darkly to counter this lightness. This transverse fracture in the proceedings is well managed by the performers as they disengage from the audience and each other, entering another world of their own. Thom Browning’s low key electronica inundates the space to create a moody uneasiness perfectly complemented by Whitney Eglington’s spare lighting design. Two medical light boxes suspended in the space illuminate the brain scans and x-rays of broken bones held up to them in classic gestures that recreate to strong effect the still moment of anguish and horror before a patient’s life or death sentence is pronounced. Law’s Suzuki-based and Trace’s circus style of repetitive choreographed movement performed with absolute focus likewise served to prolong this moment to an unnerving extent considering the real risk of injury in this context.

This was a sophisticated and interestingly constructed show—the moment of disconnect, the movement into abstraction, was similar to the act of severence performed by O’Neill in The Pineapple Queen wielding her axe, and for the same reasons. Law and Trace, by cutting ties to their own self-narratives, seemed to be staking claim to new and uncharted territory on a level basis with the audience. Given their obvious skills and commitment, it will be interesting to see how their future work develops with larger subject matter. As a footnote, I’d like to mention the salient influence I’ve been observing that OzFrank has been having on two generations now in Brisbane.

The Pineapple Queen, creators Norman Price, Lisa O’Neill, writer Norman Price, director, dramaturg Ian Lawson, performers Lisa O’Neill, Michael Coughlan, sound composer Guy Webster, lighting design David Walters, costume design Glen Brown, video design Jaxzyn; Roundhouse Theatre, Brisbane, July 28-Aug 8; Transverse Fracture of the First Metacarpal, co-devisors, performers Genevieve Trace, Kieran Law, sound design Thom Browning, lighting design Whitney Eglington; Sue Benner Theatre, Metro Arts, Brisbane, July 9-25

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg. 47

© Douglas Leonard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

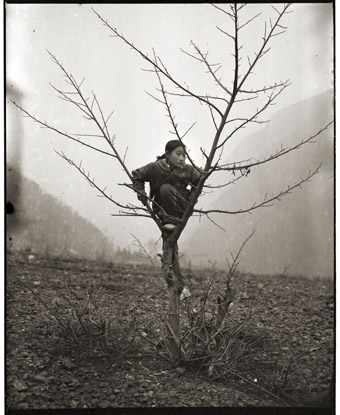

A NEW BOOK, EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC: AUDIO EXPLORATIONS IN AUSTRALIA, FROM UNSW PRESS, OPENS ‘SCENIC’ WINDOWS ONTO HIDDEN WORLDS OF AUDIO CULTURE AND CONTEMPORARY MUSIC-MAKING FOR THOSE WHO MAY HAVE BEEN CAUGHT IN ITS SPELL AND WONDERED WHERE IT ALL CAME FROM.

A NEW BOOK, EXPERIMENTAL MUSIC: AUDIO EXPLORATIONS IN AUSTRALIA, FROM UNSW PRESS, OPENS ‘SCENIC’ WINDOWS ONTO HIDDEN WORLDS OF AUDIO CULTURE AND CONTEMPORARY MUSIC-MAKING FOR THOSE WHO MAY HAVE BEEN CAUGHT IN ITS SPELL AND WONDERED WHERE IT ALL CAME FROM.

My first conscious meetings with experimental music were through a high school music camp tutor and through the older brother of a school friend. The tutor introduced me to the post-war classical experiments of total serialism, graphic scores and chance processes; the friend’s brother to the world of Severed Heads and other Australian and international manifestations of the experimental electronica that emerged in the wake of Punk. These two broad strands of activity are the primary antecedents that the editor of Experimental Music, Gail Priest, identifies for today’s Australian experimental music culture.

It’s been a long wait for a book-length attempt to document and interpret these developments in Australia and I approached Experimental Music with both excitement and anxiety. I was excited because at last an important part of the music scene of my own era and place was being represented in book form, but anxious that the book would not be up to the task—that I would find myself taking issue with the writers on everything from the book’s title to its many claims and omissions.

In attempting to meet this challenge, Gail Priest and her publishers have provided an introduction and framework for what amounts to a series of essay memoirs by a representative group of artist-commentators, each presenting and reflecting on the genre, scene or facet of the experimental music kaleidoscope they know best.

The opening quote from Jon Rose sets the book’s tone. “You can and should research and write your own history…” This is history written by the history-makers, an idiosyncratic assemblage of artists whose primary strength as commentators is the immediacy of their experience and the freshness of their memories of the cultural scenes, practices and people they write about.

A snapshot of Experimental Music’s kaleidoscopic treatment of the experimental scene is gleaned by turning to the index and dipping into the different facets of particular artists featured across several chapters. The commonalities point to the slippery and constantly evolving nature of experimental ‘genres.’ They also highlight the importance of a relatively small number of artists in catalysing the scene-making activities of the many. Indeed, the convergence of the book’s narratives around these figures (such as Lucas Abela, David Ahern, Ross Bolleter, Philip Brophy/tsk tsk tsk, Warren Burt, David Chesworth, Jim Denley, Tom Elllard/Severed Heads, Robin Fox, Ron Nagorcka, Jon Rose and Rik Rue) seems to suggest an implicit Australian experimental canon. The absence of women from this quick survey reflects the apparent rarity of influential cross-genre female protagonists, women being best represented in improv and radiophony. Does much ‘experimental’ culture have a relatively macho, or ‘boys-with-toys’ character?

Launching in from a brief sketch by Priest of the main uses of the term ‘experimental music’ and its neighbours ‘sound art’ and ‘exploratory music’ the book’s 10 chapters provide 10 slices or ‘scene-based’ views of recent experimental music in Australia. Each of the chapters is marked by the language, feel and cultural priorities of the writers and their ‘scenes’—a jumble of heterogenous voices set within the framework provided by Priest. She bookends the collection with a brief focus on the ways in which contemporary sound culture is increasingly engaging the visual.

Priest and Julian Knowles in his opening chapter define experimental music primarily in terms of what it is not, a culture marked by its spirit of opposition. The glue that binds this unruly assemblage of divergent music-makers together is the will to push or transgress boundaries, whether between music and noise, the extreme loud and soft edges of hearing, the boundaries of intention and chance, of copyright, of the nature of instruments whether found, newly created, modified or reinvented, of music with other artforms, or of the social and physical contexts of music-making.

Knowles’ introduction delivers an overview of some key festivals and concert series that have supported and promoted the DIY end of experimental music over the past two decades. He provides a sense of the background and ecology of current scenes, emphasising both the fecundity of artists, events and practices and their fragility, subject to intermittent funding and the rapid ebb and flow of venues and series, all riding on the largely unpaid energies of their artists/curators.

His sketches of What Is Music?, Liquid Architecture, the NOW now Festival and other manifestations of the contemporary listening-oriented music scene begin to flesh out sub-cultural affiliations to free jazz and improvisation, to the electronic music and multimedia work of the academy and to the more anarchic energies of noise and other more punkish music-making.

As with the other contributors in this book, Knowles’ conception of experimental music-making perpetuates the late modernist amnesia concerning the extraordinary local Indigenous and colonial musical experimenters of the previous 200 years, as described in Jon Rose’s 2007 Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address. Again, this amnesia is partly built into the publisher’s brief for this book and its UNSW Press Australian Music series companions to tell the story of the past 30 years of music in this country. This is a time frame that makes more sense in Australian classical music where there are already a handful of books dealing with earlier periods. The short focus unfortunately reduces any sense that there is a local or national heritage to be drawn on, making experimental music culture seem to be an international phenomenon to which Australians have more recently responded and occasionally contribute.

In “The Lost Decade”, Ian Andrews and John Blades flesh out the first phase of DIY activities in a scene marked by hand-made cassette releases, low-tech looping, ephemeral labels, fanzines, and constantly permutating bands and collaborations creating an apparently bewildering array of small-scale, grass-roots activity all taking place in opposition to the established music industry. This evokes the time of my early adulthood, full of familiar and half-known names that provoke a flush of nostalgia and recognition while providing a larger context for a scene that I experienced on a purely local level.

The next three chapters follow three different paths from the experimental ‘scenesters’ of the post-punk ‘lost decade’ to the contemporary network of independent listening-oriented festivals and concert series described by Knowles. Cat Hope tells the story of the rise of ‘noise’ from a band-based challenge to mainstream definitions of musical sound to a genre, and now an increasingly important aspect of experimental music across the spectrum. Shannon O’Neill looks at appropriation-based music—the sampling, mash-ups and tributes that have pushed the boundaries of copyright. He makes the interesting observation that experimental music in Australia as a whole has recently shifted towards a more ‘materialist’ focus, eschewing quotation and absurd juxtaposition for a mostly straight-faced focus on the materiality of the instruments and the physicality of sound production and its by-products. Priest and Sebastian Chan’s brief sketch of the coexistence of popular and unpopular electronic music in the rave and party worlds of the 90s fills in one more background to the ‘listening-oriented’ music culture partly created by these artists as they detached themselves from the dance scene at the start of the new century.

By this time the lists of artists and projects, known, unknown and half-familiar, cry out for more detailed description of actual practices, provided to some extent by Bo Daley’s case study of the Sydney electronic music collective Clan Analogue. The account fleshes out the mechanics of scene-making with its attendant behaviours, aesthetics and ethics, within a typically post-Punk collectivist environment that characterised many of the DIY experimenters covered in the previous chapters.

Alistair Riddell takes the reader away from scene-making and into the world of the university electronic studios of La Trobe, Melbourne University, the NSW Conservatorium and Adelaide’s Elder Conservatorium in the 1970s, characterised by the interplay between scientific and artistic mind-sets. It’s a starker version of the interplay between instrument and idea that characterises all creative music making. A similar interplay is found in the independent instrument-building activities of Sean Bridgeman’s chapter, ranging from software, through circuit-bending and the building and radical modification of acoustic instruments. Riddell ends his chapter with a plea for the continued university development of the programmer-musician in the face of a scene increasingly dominated by individual laptop artists operating in the main as end-users of third-party software rather than creative developers of new software to express highly individual artistic intentions.

Jim Denley’s chapter on ‘improv’ returns to scene-making but continues Riddell’s larger sweep of time and geography with a definition and brief sketch of the development of improv in Australia from 1972 to the present followed by a series of portraits of key artists, neatly distilling the contributions and stylistic approaches of each. The What is Music? festivals of the 1990s, founded by improvisers Robbie Avenaim and Oren Ambarchi, are seen as key in taking improv from the underground of a handful of practitioners into a visible scene with a surprisingly large and youthful following. Part of the secret of the large numbers is that improv has developed a participatory ethos in which many players move easily between the roles of audience and performer.

In “Written In Air”, Virginia Madsen introduces readers to the world of radiophonic arts, a strand of experimental sound culture emerging out of the radio sound studios of France, Germany, Italy and the UK. This tradition thrived within the Australian Broadcasting Corporation over two decades, most famously in the long-running program The Listening Room, providing experimental opportunities and resources to diverse artists interested in hybrid interplays of environmental recordings, words, instrumental music, sound effects, electronics and any and all of the arts of sound. Her hymn of praise to peripatetic ex-pat Australian Kaye Mortley’s radiophonic oeuvre had me wanting to hear more and wishing for spaces today where this work might more readily continue to be heard. Gail Priest’s accompanying CD selection of examples barely skims the surface of the many scenes and artists in this book, but does provide a number of tantalising glimpses, including an extract from Mortley’s Exilio from 1999.

Experimental Music: audio explorations in Australia fills a cultural gap, documenting local audio culture and providing a useful taxonomy of the main modes of practice in Australia frequently understood as ‘experimental music.’ A contentious aspect of the book will be the very Sydney-centric roster of contributors. Some of these do better than others in elaborating a national perspective, but the provocation is there to counter the shortcomings with more books and articles, offering alternative readings and the coverage of artists and local scenes not represented here.

And the publication of such a book has a valuable legitimising effect, building wider awareness of the experimental scene’s traditions and key antecedents and therefore of its place in the broader culture. There is of course some ironic tension in the legitimising of experimental music culture given that culture’s commitment to opposing and dismantling orthodoxies. At what point does an experimental musical form/scene/process/aesthetic/…cease to be ‘experimental’ and become part of received culture? Nevertheless it’s healthy for any culture to foster historical awareness among its participants if only to guard against the uncritical acceptance of new ‘experimental’ orthodoxies.

Gail Priest, editor, Experimental Music: audio explorations in Australia, UNSW Press, 2009, ISBN 978 1 921410 07 9. The UNSW Press Australian Music series was supported by the Music Board of the Australia Council.

www.experimentalmusicaustralia.net

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg. 48

© Stephen Adams; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

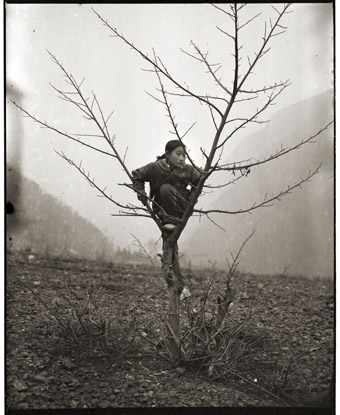

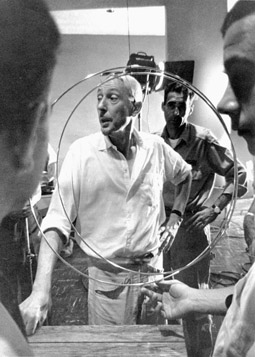

Perspective, Soundstream: Adelaide New Music Festival, Dave Palmer

photo Jia Zhuang

Perspective, Soundstream: Adelaide New Music Festival, Dave Palmer

SOFIA GUBAIDULINA’S CLOWN STEALS THE SHOW AT THE OPENING NIGHT OF ANMF. A TROMBONIST IN COSTUME ENTERS THE AUDITORIUM AND INTERRUPTS A SAXOPHONE QUARTET PERFORMING ON STAGE IN HER VERWANDLUNG (TRANSFORMATION). THUS BEGINS AN ARGUMENT, THE DIFFERENT INSTRUMENTS AND THE PLAYERS REPRESENTING OPPOSING MUSICAL AND CULTURAL FORCES, WITH THE RED-SMOCKED TROMBONIST, THE OUTSIDER, CHALLENGING THE ESTABLISHMENT.

In a program note, Russian composer Gubaidulina states that “the trombonist stands for a Russian archetype, the holy fool or yurodivy.” The yurodivy “plays the fool, while actually being a persistent exposer of evil and injustice.” The clown flirts with the audience—the people—to gain their favour as he attempts to disrupt the saxophonists.

Gubaidulina’s Transformation (2003) is a theatrical composition whose message has universal significance. Unable to suppress the formidable saxophonists, the clown sits dejectedly to remove his makeup while a cellist and a double-bassist take up the musical line. Trombonist Dave Palmer is splendid as the clown who ultimately joins the sax and string ensemble, abandoning his outsider identity by covering his costume and performing from the same score as the others who now accommodate him, developing a canon form to indicate the echoing of new ideas. The work ends with the solitary beat of a tam-tam by a performer-witness in a red shawl who has sat silently by throughout, patiently awaiting her moment, signalling a beginning rather than an end.

Adelaide is a city of many festivals, but until recently hasn’t had a dedicated new music event. The excellent program for this, the second Adelaide New Music Festival, spans a century of composition, attracting good audiences with outstanding performances. In opening the ANMF, former Adelaide Festival of Arts director and ANMF patron Anthony Steel noted how difficult it is to get audiences outside of the comfort zone of the Adelaide Festival.

ANMF Artistic Director Gabriella Smart’s theme for this ANMF is the sacred and profane, and a central character is the clown or fool, who also appears in the closing concert at Coriole Vineyards on the Saturday afternoon.

At St Peter’s Cathedral, Transformation was preceded by a performance for cello, choir, celeste and percussion of Gubaidulina’s Sonnengesang (Canticle of the Sun, 1997), which sets a text by St Francis of Assisi, pays homage to revered Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and attests Gubaidulina’s own faith. In this fabulous work, the choir acts as the orchestra for what is in effect a cello concerto as well as a canticle, and stands in for parishioners. The percussionists rub the moistened rims of glasses that represent chalices, creating a whining sound that blends with the cello and soprano voices to create an ethereal effect. Tubular bells evoke the sound of church bells. Later, the cellist puts down his instrument and walks about the choir as he plays a flexatone with a bow, eliciting a responsory as part of the canticle and thus directing the choir, before returning to the cello to bring the work to its climax.

Sonnengesang is thus based on two distinct musical forms, actively linked by the cellist, and on sacred and profane traditions. Gubaidulina asks much of the soloists in her work, as musical performance is extended into dramatic performance with detailed stage directions. Netherlands-based Australian cellist John Addison, a Gubaidulina specialist, gave a spellbinding account of this complex and demanding piece, and the Adelaide Chamber singers under Carl Crossin were magnificent.

On the second night, Adelaide’s Zephyr Quartet gave a recital exploring Jewish musical traditions, including Argentine-born composer Osvaldo Golijov’s breathtaking Yiddishbbuk, Inscriptions for String Quartet (1992), a reconstruction of music to accompany a set of apocryphal Jewish psalms. The work unfolds as a series of dramatic gestures, with notes held long like screams, and moves on to fragmentary tunes that are frighteningly abbreviated. Also included were Adelaide composer Quentin Grant’s Klezmer Variations and Melisande Wright’s suite Lighter Shades of Pale, both of which foregrounded the unique Klezmer tradition with its seductive, danceable rhythms.

Melbourne’s Anthony Pateras and Robin Fox are internationally renowned but had never before performed in Adelaide. The third night was theirs, Pateras giving a mesmerising performance on prepared piano and Fox a wondrous rendition of his laser and sound show. They formed a dynamic duo to conclude with several short pieces for synthesisers, laptop and Pateras’ sampled voice, with Pateras manipulating the synthesiser as frantically as he had the piano.

On the Saturday there were morning and afternoon concerts in the Barrel Room at the delightful Coriole Vineyards, with a sumptuous lunch in between. The morning session comprised five exquisite short works by Australian and international composers: Pierre Boulez’s Anthèmes (1998) for solo violin (James Cuddeford), Tan Dun’s 1989 intensely introspective Traces for solo piano (Gabriella Smart), Adelaide composer David Harris’s Chinook (2009) for a trio of clarinet (Peter Handsworth), cello (Addison) and piano (Smart), Brett Dean’s Demons (2004, Geoffrey Collins, flute) and finally Hannah Kulenty’s A Fourth Circle (1994) for cello (Addison) and piano (Smart). Harris’s recent work is described as “expressive post-romanticism”, and in Chinook (one meaning of the term is ‘a warming wind’), he adroitly weaves tonal and chromatic lines and contrasting rhythms into a passionate and satisfying composition, highly resolved but with a delicious hint of uncertainty, like a complex rhetorical question. Kulenty’s is a stunning piece, emotionally overwhelming and brilliantly executed. Following a long piano passage like a tolling bell, the cello begins a series of questioning phrases that become incessant, using short, microtonally notated glissandi, crying imploringly—why? why? why? An intense crescendo is then slowly relaxed, with the glissandi curling downward. I was speechless for some time afterwards, so affecting were the writing and the performance.

In the afternoon was a single work, Schoenberg’s classic Pierrot Lunaire of 1912, which, though it is the earliest work in the festival, seems to draw together the threads of the previous four concerts—it was Schoenberg who championed chromaticism; it features the clown who is alienated from society and it speaks of tragedy and loss. Schoenberg set 21 poems to music, to be delivered using sprechgesang, a form of declamatory speech-like singing, in which the reciter slides into and out of notes. Greta Bradman’s performance as Pierrot was outstanding, and she was ably supported by a wonderful ensemble of Smart, Cuddeford, Addison, Collins and Handsworth under the firm direction of Pierrot expert Charles Bodman Rae.

This ANMF comprised an exemplary program of local and overseas works that reflect music’s recent development, thoughtfully curated by the indefatigable Gabriella Smart. Audiences benefited from detailed program notes, gaining a much expanded musical awareness. Especially, we heard music that also needs to be seen, recognising that the playing of an instrument is the enactment of a theatrical role.

Soundstream Adelaide New Music Festival, artistic director Gabriella Smart, Adelaide, Aug 19-22

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg. 49

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

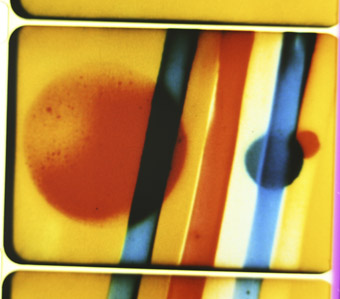

Brigid Burke, Scratching (video still)

courtesy the artist

Brigid Burke, Scratching (video still)

UNDER THE GUIDING HAND OF CHAIRMAN JAMES NIGHTINGALE, THE NEW MUSIC NETWORK HAS EXPANDED ITS CORE PROGRAM OF ESTABLISHED ENSEMBLES TO INCLUDE A RANGE OF CONCERTS BY SOLO ARTISTS AND EMERGING GROUPS OF CONTEMPORARY CLASSICAL MUSICIANS. NOT ONLY IS THIS PROVIDING PROFILE FOR NEWCOMERS BUT, AS MANY OF THESE ARTISTS EMPLOY MORE EXPERIMENTAL COMPOSITIONAL AND PERFORMANCE METHODOLOGIES, IT IS ALSO BEGINNING TO BLUR SOME OF THE PERCEIVED BOUNDARIES BETWEEN THE CONTEMPORARY CLASSICAL (DOT-BASED) CAMP, AND THE EXPLORATORY (IMPROV, LAPTOP, AUDIOVISUAL) GANG. TWO RECENT CONCERTS IN THE NEW MUSIC NETWORK MINI SERIES ARE INTERESTING ILLUSTRATIONS OF THIS.

solo perspective 2

Featuring Brigid Burke, Mark Cauvin and Michael Fowler, this concert offered three contrasting approaches to expanding the artists’ relationship with their instruments. The evening began with Burke who composes for clarinet and video. Her first piece, Island City (2009), is energetic, with sharp vocal utterances, sibilances, intricate clarinet trills and sustained split notes. It is accompanied by snapshots in a grid format of scenes from the coastlines of Victoria and Ichagaya in Japan and a live feed of a seahorse in a fishbowl. The effect is of faded and fragmented recall, where perhaps it’s not the event itself you recall, but rather the memory of the photograph.

Three Sounds on Buildings (2004) offers a more cinematic approach, the extended techniques applied to the B-flat clarinet completing the stark, yet somehow affectionate visual composition of old buildings, graffiti, corrugated iron textures and long pans taken from a train window. There is a sense of nostalgia, perhaps due to the work’s original conception in 1992 (for slides), and while a well-explored visual field, the composition of music and vision provides a satisfying narrative. The final two pieces, Roses will Scream (2007) and Scratching (2009), incorporate live video in a more essential way, overlaying live feeds to affect textures and transparencies on pre-recorded material, both photographic and hand drawn—an impressive feat of multitasking. Both pieces for bass clarinet explore the rich range of the instrument, finding an elasticity to its tone and timbre but with an agile, melodic touch. Brigid Burke’s compositional strategies and integration of visual elements make her performance quite unique.

Mark Cauvin is a man driven to explore every sonic possibility of his instrument, the double bass, thus Stockhausen’s Plus Minus Nr.14 (1963/2009), a graphic score of symbols and instructions, offers the perfect vehicle. In this performance you get a tangible sense of the performer as co-composer rather than interpreter of the work. There are very few pure notes, the interest lying more in the noisy artefact—the scrape, rattle and hum. However, rather than an improviser’s impulsive adventures with these sonorities each of Cauvin’s responses is deliberately extracted, measured and placed. Musician and instrument seem to be in an intense symbiotic relationship as Cauvin summons extraordinary sounds, the correlation of gesture and sound absolutely pure, non-theatrical, yet utterly engaging. Through such demanding material Mark Cauvin creates a sinuousness and continuity between jagged sounds and actions to deliver a mesmerising performance.

There is the sense that Cauvin is also co-composer in his second piece, David Young’s No More Rock Groynes (2009)—a small watercolour score interpreted through a prepared microphone applied to the double bass. Once again, notes with neat frequencies are abandoned, replaced by scratches, squibbles, squeaks, soughs and sighs—a study in how a large instrument can make small and subtle sounds.

The final soloist was Michael Fowler, a pianist also well versed in synthesiser programming and research into the intersection of architecture and acoustic design. Both his pieces explore the piano in duet with machine. The first, Downtime (2005) by Benjamin Boretz explores the interplay between piano and a pre-recorded midi-instrument track. It is spacious, the midi palette unfolding methodically from synthesised drums through to tuned percussion. Each ‘player’ takes turns exploring tones, timbres and the space between. The unaffected midi instruments seem so synthetic in comparison with the deep resonances of the grand piano, drawing our attention to the fundamental timbral nature of the sounds. In Reflections (1975) by Milton Babbit, the machine in question is the behemoth RCA Mk II, the first programmable electronic music synthesiser that few besides Babbit and his colleagues at Princeton University ever managed to utilise. The recorded machine offers a palette of ‘sounds of the future’ as envisaged in 1957, playing spiky polyphonic sequences impossible for human reproduction. Babbit was interested in the attack of the note and as Michael Fowler and pre-recorded material duel, the frequencies tumble over and crumble into each other in what essentially becomes an invigorating onslaught of notes. A fittingly vibrant end to the concert.

golden fur

Golden Fur is a relatively new collaboration between Melbourne musicians Samuel Dunscombe (clarinet, laptop), Judith Hamann (cello) and James Rushford (piano, viola), and they offered a nicely varied program of five pieces. Liza Lim’s Inguz (1998) for clarinet and cello is the perfect opener—both angular yet supple, as clarinet and cello drone slip around each other, their tonalities intriguingly intermingled into an all new sounding instrument. Trio No. 5 (2009) commissioned by the group from Kate Neal, is similarly well suited, allowing the trio to explore high energy, gestural playing, with cycling fragments, replete with dramatic pauses and eruptions. (The program note does suggest that the group explores ‘theatre and ritual’—perhaps a little overstated for some crisp gestures and the plastic wreath that adorns the clarinetist’s locks.)

Rushford’s interpretation of Music for Piano with Slow Sweep Oscillators (1992) by Alvin Lucier is in keeping with the choices of Michael Fowler, however this work focuses on psychoacoustic interplay. As piano resonances cut through the pure sine tone to produce swirling and beating effects, the sound becomes thick and tangible. Rushford’s touch is gentle and evocative allowing the beauty and meditative nature of the piece to come to the fore.

The two final works utilise graphic scores. The first, Parallel Collisions (2008) by Marco Fusinato (both a sound and visual artist), employs a series of visual provocations and stopwatches. It appears from the similar timbral and rhythmic responses (and the title) that each musician plays a musical gesture parallel to the image, which I found a little unsatisfying, particularly as the audience doesn’t get to see the visual stimulus. While I don’t need to see a notated score to experience the music, the rhetoric the group employs about the ‘intersection of visual arts and music’ suggests that the audience might benefit from some sharing of the visual element.

For Jaap Blonk’s Transiberian Part 2 (2001), the trio take to the floor, Rushford playing an amplified viola, Dunscombe a laptop and Hamann laying the cello down for some beating. Listening to their jagged, raspy exploration, I can’t help wondering if it would be more interesting—more organically cohesive—if the musicians threw away the score and simply improvised. It’s not that the sounds irk me, rather I wonder if corraling them into the structural conceit of the visual score makes for the most interesting use. But I have to out myself as being from the no-dots music camp, part of the reason I found the explorations by the musicians in these two concerts particularly engaging and challenging. They revealed the increasing slippage between current contemporary classical and exploratory sound and music practices—a trend that thankfully the New Music Network appears more than eager to encourage.

New Music Network, Solo Persepective 2: Brigid Burke, Mark Cauvin, Michael Fowler, Aug 16; Golden Fur: Samuel Dunscombe, Judith Hamann, James Rushford, Sept 6; Recital Hall East, Conservatorium of Music, Sydney

The New Music Network is calling for concert proposals for the 2010 Mini Series, deadline Nov 30, 2009; www.newmusicnetwork.com.au

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg. 50

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

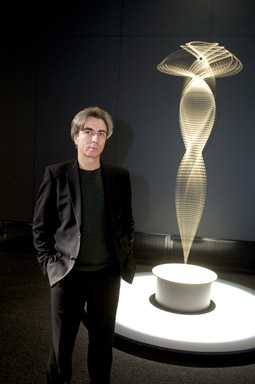

Soloist Graeme Jennings, Elision Ensemble

photo Marc Grimwade

Soloist Graeme Jennings, Elision Ensemble

RICHARD HAYNES MAKES THE E-FLAT CLARINET TALK IN HIS ENCHANTING RENDITION OF MICHAEL FINNISSY’S MARRNGU. IN THE YOLGNU DREAMTIME TRADITION MARRNGU IS THE POSSUM MAN, AND FINNISSY’S WORK IS ABOUT MARRNGU’S STORY, A STORY TOLD IN MUSIC RATHER THAN SPOKEN WORD.

Finnissy’s 1982 composition resembles speech in its lilting, dramatic tones, gathering in intensity and emotion as the story unfolds, the linear phrasing mimicking an emphatic story-teller. Though smaller and higher pitched than the more common B-flat clarinet, the E-flat clarinet has a rich, creamy sound that is particularly evocative in suggesting the human voice. Haynes builds deep, complex character into the music, and his playing of this demanding work is effortless and beguiling.

Elision concerts are like no others—showcases of exquisitely crafted works for solo instruments or small ensembles that push the limits of instrumental performance. This evening was set out as two one-hour concerts, each of five short works written between 1981 and 2009. The selection especially showed how instruments can express the human voice and tell a story.

The first concert opened with Tristram Williams’ solo trumpet performance of Liza Lim’s Wild Winged-One (2007), which Lim reworked from her opera The Navigator. The trumpet represents the Angel of History, which, according to the program notes, is a “half-human half-animal bird figure of prophecy and witness.” Williams creates a language of sound forms, combining breathing through the trumpet with scatty motifs to form a kind of declamatory speech. This was followed by Richard Barrett’s inward (1994-95), a kind of dialogue that opens with gently tinkling percussion (Peter Neville) followed by a long, lyrical exposition for flute (Paula Rae). Again the performer’s own voice is heard through the instrument. The dialogue is ultimately an internal one, a troubled soliloquy culminating in a long, high exclamation.

For Jeroen Speak’s Silk Dialogue VI (2007), scored for string quartet, E-flat clarinet, flute and five snare drums, the six performers are seated in a semi-circle, and between each is a drum they beat periodically to mark each section of the work. These forceful junctures frame the music as a series of discrete, almost visibly geometric shapes, culminating in a drum crescendo as if concluding a story told in exquisite drawings. The E-flat clarinet part leads the work, and Speak’s writing for it is persuasive—it was commissioned by Haynes, who is again brilliant, and, for me, Silk Dialogue VI is the centrepiece of the evening. The writing is finely crafted and the threads are densely woven yet light and airy, creating musical forms that swirl around. The conductor, Hamish McKeich, holds it all together wonderfully.

The first concert concluded with another extended solo work—Roger Ramsgate’s Ausgangspunkte (1981-82), a very intense piece for oboe that requires a herculean effort from the performer, Peter Veale. The work is complex and detailed, requiring almost as much concentration from the listener as from the performer.

The second concert opened with Benjamin Marks’ Perdix (2009) for trumpet and vibraphone, though the latter comes in only towards the end, gently cooling a very heated trumpet solo. The writing is agitated but quizzical, again a kind of soliloquy, but calm is restored at the conclusion. This is followed by Graeme Jennings performance of Liza Lim’s Philtre (1997) for solo Hardanger violin, a more introspective piece that exploits the unique resonances that emerge from the violin’s sympathetic strings.

Richard Barrett’s Wound (2009), for violin, cor anglais, E-flat clarinet and cello, was evidently influenced by the paintings of Francis Bacon in which the action is framed within the canvas. The violinist stands opposite the other performers in animated exchange with them, and, for me, the composition posits the violin as interviewee and the other instruments as inquisitors, or perhaps the violin as a bird and the others as its cage. The human voice proper reappears in Robert Dahm’s absorbing work the flesh is grammar (2009), for a wind and brass septet that includes contraforte, a reed instrument that produces the deepest notes. The text in the work is whispered or spoken by the performers, combining with densely layered instrumental textures to produce a juicily corporeal effect. Your attention shifts back and forth between the compositional structure and the instrumental timbres and resonances, with the personality of each instrument becoming a character in a play.

In many works, the performer complements the composer by developing novel techniques to realise new musical forms and new aesthetics. Elision concerts are precious opportunities for the creation and performance of innovative music by the best composers. They demand virtuosic playing and reward committed listening.

Elision Ensemble in Session, live broadcast, Iwaki Auditorium, ABC Centre, Southbank, Melbourne, July 28

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg. 51

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

AS PART OF THE LIQUID ARCHITECTURE FESTIVAL’S 10TH ANNIVERSARY, I WAS COMMISSIONED TO TRAVEL ALONGSIDE THE ARTISTS TO EACH OF THE PARTICIPATING CITIES AND WITNESS THE PERFORMANCES, ATTEND FORUMS AND TAKE PART IN INFORMAL DISCUSSIONS, WHILST SHARING MY THOUGHTS ON THE LIQUID ARCHITECTURE BLOG AS A MEANS OF INCREASING THE DIALOGUES BROUGHT ABOUT BY THE EVENT.

This initiative came to be in response to the dissatisfaction of Liquid Architecture organisers and artists with the level of critical feedback generated following past festivals. In touring, I learnt that such critical exchanges exist, but sadly are not often formalised or committed to print.

I saw the entirety of Liquid Architecture and in a new light, as a multifaceted event. I witnessed several very different festivals across Australia, reflecting the collaborative nature that founding director Nat Bates often mentions when discussing Liquid Architecture. It was also clear to me that after 10 years the festival has entered a phase of reflection and self-critique.

The multifaceted nature of the festival raises many questions; on the road with LA10 the vibrancy of sound arts and exploratory music practices in Australia was evident. Tura New Music in Perth, ROOM40 in Brisbane, Alias Frequencies and Plum Industries in Sydney, On Edge and The House of Falcon in Cairns as well as Cajid Media in Central Victoria were co-producers with Liquid Architecture based in Melbourne. They brought their own organisational practices to the hosting of the international artists toured by Liquid Architecture. It should be noted, however, that LA10 was one tier of what these organisations do yearly (often collaboratively, across states). So, beyond providing international artists, what additional role does Liquid Architecture play?

Over the 10 years that Liquid Architecture has grown as a brand, a certain stability and perhaps expectation of an aesthetic and presentation standard has developed. It is safe to say that the festival’s scope is not (and would not claim to be) an accurate account of all exploratory sound practices currently engaged in globally. International performers travelling to the festival tend to be European (and to open an argument that I must start and end here for the sake of brevity) male, and often of certain European avant-garde music traditions that perhaps reflect the tastes of the Melbourne organisers.

It could be argued that the true variety in the festival’s programming is the assortment of local artists. The usual international component of Liquid Architecture is likely to be, as one friend noted in passing, “men with machines.”

So for many it’s disappointing that Liquid Architecture’s palette of performers reflects not so much a survey of international contemporary practice (as perhaps the Melbourne International Biennale of Exploratory Music in 2008 did more successfully) as appearing to be a specialist music organisation supporting a particular tradition.

However, the festival has created greater access to experimental music than other events. This is not true of all the states that Liquid Architecture travels to, but the attendance at this year’s North Melbourne Town Hall concerts proved that 10 years has helped develop an audience that wouldn’t be accommodated at the numerous smaller events occurring constantly in Australian underground music scenes.

At a forum organised by Within Earshot, a collective of RMIT University Fine Art (Sound) students, there was a lively debate surrounding dissatisfactions with the first Town Hall concert. The point was made that for new audiences, the concert did not present a varied program of what is truly taking place in contemporary exploratory music cultures both in Australia and abroad. For first timers, it would have shown merely one (rather Euro-centric) take on the sonic arts. Does this require the festival to be the provider of a perhaps impossible survey? Is it about the festival miscommunicating its motivation? Festival co-founder and director Nat Bates often states in conversation that if the festival causes disagreement amongst patrons leading to them starting their own event, that would be a success. But for LA’s new (and growing) audience, does such a view carry weight? Yes, there are plenty of new events being organised constantly by those who wish to get people thinking about sound. But, LA 10’s satellite events at Horse Bazaar and the Within Earshot for RMIT students did not feel like a considered part of the festival.

The very fact that Liquid Architecture has grown into a major, national event reveals that the exploratory sound cultures of its focus are not as niche as once thought. It was my sense in traveling with the festival that the transition from Liquid Architecture’s point of conception as a vessel for presentational opportunity to its current incarnation, happened too quickly for the festival organisers to keep pace. Certainly, I gathered a sense of dividedness as to what LA10 was trying to deliver. The organisers themselves might be in two (or more minds) about it. The festival’s funding too, does naturally provide expectations about what Liquid Architecture should deliver.

LA’s directors are working hard to consider not simply avenues of improvement but how to solidify Liquid Architecture into a stable, pertinent incubator for a critical exchange on sound arts. There are other opinions about what Liquid Architecture could be, but so long as these thoughts remain word of mouth perhaps we will not witness much change.

Liquid Architecture 10, June 24-July 12, www.liquidarchitecture.org.au

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 pg. 52

© Jared Davis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

AS CHRIS REID WRITES IN HIS REVIEW OF THE SOUNDSTREAM NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL (P49), SOME MUSIC HAS TO BE SEEN AND NOT JUST HEARD. BRISBANE-BASED TOPOLOGY’S EAST COAST TOUR GAVE US A LIVE, WORKING BAND WITH A CASUALLY THEATRICAL AND JAZZY SPONTANEITY YOU MIGHT NOT BE EXPECTING FROM THEIR NEW CD, BIG DECISIONS, WHICH OFFERS OTHER PLEASURES. SYDNEY’S HALCYON DELIVERED A MORE FORMAL CONCERT WITH AN OPERATIC INTENSITY IN WORKS WITH BIG AMBITIONS AND VISIBLY COMPLEX INTERPLAY BETWEEN PERFORMERS.

Robert Davidson aside, Topology’s musicians are an unassuming bunch onstage, but the bassist’s amiable mc-ing, occasionally miming to the voices of Australian politicians in his Big Decisions: The Whitlam Dismissal (2000) and having the audience chant “We want Gough!” on cue, add fun to the occasion. The concert opened with Bernard Hoey’s Chop Chop which briskly marshalled a big band sound from small forces. After John Babbage’s lyrical tenor sax realisation of a Pat Nixon aria from John Adams’ Nixon in China (from the Topology CD Perpetual Motion Machine), Hoey’s viola improvisation on Davidson’s Exteriors (a response to Southern Indian temple architecture) ranged through meditative warblings to passionate flourishes supported by tabla-ish taps on Davidson’s double bass. Babbage’s witty arrangement of Cold Chisel’s Cheap Wine starts out 50s cool jazz and then proves Topology can rock.

The concert centrepiece, Big Decisions, was at once entertaining and chilling (it never fails to vividly remind me of that fateful November 11th). Other works on the program were not familiar but excited interest: Babbage musing on the genome (X174; 2003); Davidson dextrously exploiting the Australian-American rhythms and twang of an ex-Brisbane Christian fundamentalist, Ken Ham, who’s now big in the USA (Generation after Generation; 2008); and another Davidson work, Round Roads (2008). The latter was triggered by a bicycle ride in Canberra that recalled childhood life there including a bushfire, the music oscillating between sweet reflectiveness, potent piano-bass propulsion and some dramatic sax interpolations.

The Sydney duo, Halcyon (soprano Alison Morgan, mezzo-soprano Jenny Duck-Chong) gather composers, instrumentalists and other singers around them to create distinctive, inventive concert programs. Extreme Nature featured bold new works from expat composers recently returned to Australia, Elliott Gyger and Nicholas Vines.

Gyger’s From the Hungry Waiting country (2006) draws on Australian poems (mostly of an older generation: Harwood, Stow, Riddell, Hart-Smith, Buckley, Hope) and Near Eastern religious texts in response to “a profoundly ethical dimension to the emerging ecological crises” (Gyger, program note). Morgan and Duck-Chong were joined by soprano Belinda Montgomery and mezzo Jo Burton to execute the demanding interweaving and layering of texts, surprising glissandi and humming, buzzing insectile vocal noise. Genevieve Lang’s harp entwined beautifully and at times dramatically (buzzing too and twanging) with the singing, making the instrumental interplay with the four superb voices the highlight of the work. It was fascinating to watch the exchanges between these artists, heightened by the various re-groupings of the singers, with the harpist a logical extension of the line-up rather than as sidelined accompanist.