Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

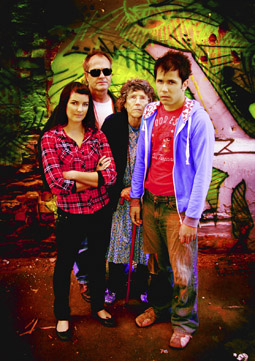

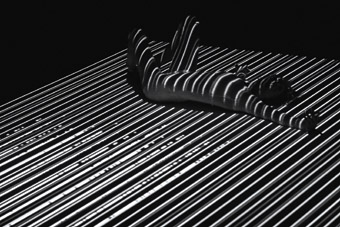

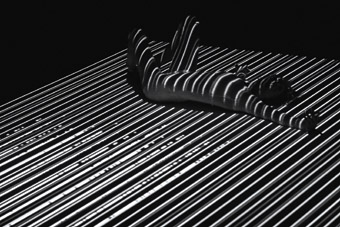

Collars, Alexandra Gillespie & Somaya Langley

photo courtesy of the artists

Collars, Alexandra Gillespie & Somaya Langley

BILL BRYSON ONCE DESCRIBED CANBERRA AS “A CITY HIDING IN A PARK”; A PITHY EXPRESSION OF THE QUIET, DISPERSED FEEL OF OUR NATION’S CAPITAL. IT’S NOT AN ABSENCE, THOUGH; LIKE BRYSON SAYS, IT’S A SENSE OF CONCEALMENT, OF UNSEEN LAYERS.

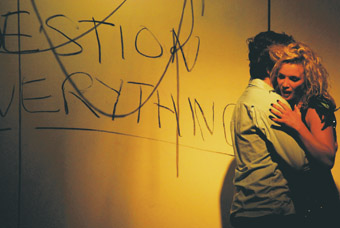

The Collars of Alexandra Gillespie and Somaya Langley’s installation stand in clusters in dimmed exhibition space. Each collar is a found object, collected from the artists’ friends and families, then detached and installed at the height of each owner; so as we enter the exhibition space we sense a crowd of absent bodies, grouped into little social clusters. Framed this way, the power of the collar to confer and express identity is inescapable; these swatches of fabric expand in our imagination into whole characters. Another layer: inside each collar, a single electroluminescent word glows, on and off; the word is keyed into spoken text, from the collar’s owner, dispersed in an immersive soundtrack.

The work is beautifully poised between intimacy and abstraction; between warm, sociable glimpses of the collars’ owners, and the formal control of the minimal stands, the cool glow of the texts. The sound field and the hovering collars give the work a heightened sense of spatial depth and interrelation; a network aesethetic, but one that is also absolutely material, made of wire and fabric, punctuated by the solenoid clicks of the switching circuits. As our personal interactions become increasingly abstracted and digitally compressed, we need more social machines like this, sourced from right next to our skin, evoking layers of our experience that don’t fit into a status update.

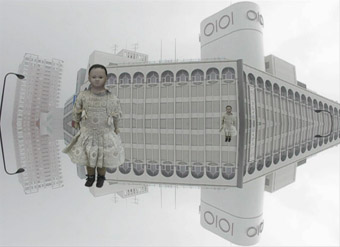

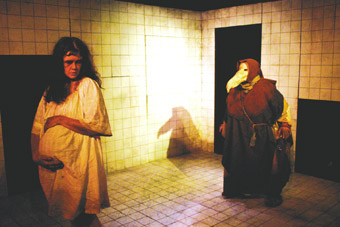

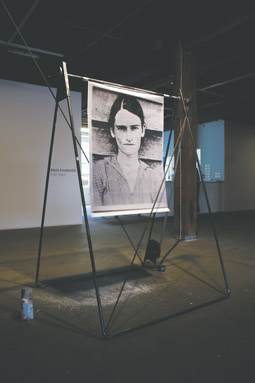

As its title suggests, Chris Fortescue’s LiminalTransitions dwells in a similarly poised threshhold space: between randomness and order, information and noise, foreground and background, intention and accident. In the Naturalism08 series Fortescue scans scraps of newsprint and packaging, then passes the source material through a set of geometric rotations and reflections. Structure inevitably emerges from these abject, crumpled things; what started as meaningless form acquires a sense of organic integrity. The results are visually seductive but suggest an ambivalence about form, structure, even beauty; if it is just junk with a dash of symmetry, where does this leave us?

Fortescue channels Duchamp in several works here; his Rectified Searches are low-fi digital images sourced from web searches for “Road”, “Fog”, and “Chris.” Duchamp’s “rectified” works are found objects subjected to a slight intervention or manipulation—L.H.O.O.Q, a cheap print of the Mona Lisa with a pencilled-on moustache, is the best-known example. Fortescue digitally rectifies his modern readymades—extrusions from the networked collective consciousness—decimating the face of each Chris into a pixel grid, slicing and transposing discs from the Roads. These minimal interventions throw the found images off balance, leaving the viewer suspended in their sense of hybrid, decentered agency.

Liminal Transitions, Chris Fortescue

photo courtesy of the artist

Liminal Transitions, Chris Fortescue

Fortescue’s Resettings is his most successful manifestation of this networked or distributed authorship. Here he works with, and between, Michael Heiser’s land art work Double Negative, and Polish artist Edward Krasinsky, whose installations and exhibitions were often bisected by a horizontal line marked in bright blue tape. In Resettings Fortescue has wrapped rocks from the site of Double Negative in metres and metres of Krasinsky-blue tape. The resulting objects are intense sculptural forms in themselves: taut, shiny little capsules of…what? In the accompanying essay the artist teases out the network of resonances, coincidences and nodal events that unfold from the work; it becomes an expansive meditation on the mingled, tangled causalities of being in the world, against the simple-minded fiction of intention.

airConResonator literally hovers over the ANU School of Art exhibition space: it appropriates the air conditioning ducts that span the ceiling, miking them up and feeding their background noise through a filter, then piping it back into the room. Visually the work is barely there: two white walls—in fact giant resonators—each with a single, shiny speaker cone embedded. Even sonically the amplified air con is a diaphonous pillow of sensation, apparent only on close listening. The work tunes us in to the edges of aural perception, pushing the background forward just enough so that, suddenly, we hear it everywhere. Like the crumpled chip packets in the Naturalism prints, air con noise is waste, chaos; but acoustically, noise contains everything, all frequencies, all possibilities, all structure. And the ducts are physical resonators that double as readymade metaphor; a networked distribution system but also, as in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, a secret, hidden world, where everything is connected. Very Canberra, really.

Alexandra Gillespie and Somaya Langley, Collars, Canberra Contemporary Art Space, March 26-May 2; Chris Fortescue, Liminal Transitions, ANU School of Art Gallery, Canberra, Jan 28-Feb 6

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 30

© Mitchell Whitelaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

L–E–D–LED–L–ED, dilight inc. (Japan), 2007, Ars Electronica Centre

photo Alex Davies

L–E–D–LED–L–ED, dilight inc. (Japan), 2007, Ars Electronica Centre

IT IS HARD NOT TO FEEL DAUNTED BY YOUR FIRST SIGHTING OF LINZ’S SPARKLING NEW ARS ELECTRONICA CENTER. IF YOU SEE IT FIRST AT NIGHT (IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO MISS), THE COLOURED LIGHTS OF ITS FLASHING FACADE SHOUT ITS SIGNIFICANCE ACROSS THE DANUBE TO THIS SMALL AUSTRIAN CITY AND ITS DETERMINATION TO EXHIBIT THE FUTURE. ONCE INSIDE, HOWEVER, THE MUSEUM IS ENTIRELY MANAGEABLE. THE QUIRKY TURNSTILES AT THE ENTRANCE SET A LIGHT-HEARTED TONE, DEFLATING TO LET YOU PASS AFTER SCANNING YOUR TICKET.

The basement is arranged into a set of public ‘labs’ staffed by enthusiastic young assistants in orange uniforms who are eager to explain and demonstrate the exhibits, while simultaneously preventing any robot injuries or deaths. The Robolab is a lively buzz of human and machine voices, by far the most popular part of the museum and home to a very decent population of working prototypes, including Hexpod who plays soccer, Plenpark who dances, and Merz who sulks when you don’t pay her enough attention. Some may complain that this is a surface representation of robot genealogy, but a comprehensive survey of such a field would be difficult in any single space.

The highlights are The Haptic Radar which, when worn, allows you to navigate the space of the museum by responding to a series of rather unpleasant pulses to the perimeter of your head, and Philip Beesley’s elegant Hylozoic Soil, a huge mechatronic organism whose tentacles react as you approach them.

The Biolab tries hard to set a scientific atmosphere: white lab coats hang on the wall, and Petri dishes and test tubes fill the shelves. But all that is here is a disappointing set of light and electron microscopes, an exhibition of cloned tobacco plants and a DNA scanning station, all of which might be interesting if they were available for use, but seem like part of a technology trade show than anything to do with electronic arts.

The Fablab is another technology showcase, housing a remarkable 3D printer and Airdrawn, a three-dimensional design interface. However, with the help of assistants, you are invited to experiment with them. This is where it all gets very Questacon, and of course, kids love it.

LevelHead, Julian Oliver, Ars Electronica

photo Alex Davies

LevelHead, Julian Oliver, Ars Electronica

The Funky Pixels area, also in the basement, needs some devoted time. Offering a tranquil antidote to the science labs, the “shoes optional” lounge area has modular cushions, street art décor, and mood lighting. You can just sit around, playing with a range of experiments in interactivity. Although it is not perfectly installed, Julian Oliver’s Levelhead is as well-loved as ever, judging by how worn the cubes of the interface are. If you are patient enough, you can navigate through the elegant levels of his Escher-like labyrinth.

From the basement, I make my way up to the Deep Space theatre, which has a show on rotation every hour or so. This exhibit presumably replaces The Cave in the old AEC, famous as a pioneering VR environment for commissioned projects. Entering the theatre, we are handed 3D glasses and deep house music plays as we find positions. But the shows are uninspiring. Papyrate’s Island, an interactive 3D game could be great to experience if you could control and navigate the space. As a demonstration, however, it is more disorienting than fascinating.

The presentation of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper preserved as 16,118,035,591 pixels seems to be merely a way of using eight high definition projectors. Is this better than seeing the painting itself? Such unprecedented level of detail may be technically impressive, but adds no magic to da Vinci’s vision, even with the operatic soundtrack. There are other films on, but most of them leave you feeling you’re in an inferior Imax theatre with no seats (or popcorn). One can only hope that Deep Space will be used more creatively in the future.

One floor up is a retrospective of the work of Berlin design lab ART+COM. Installed on shipping crates and wooden palettes, the focus here is interdisciplinary experimentation: structural models, prototypes and documentation of new media research projects. The refreshing aspect of this floor is that, as a model for documenting projects, it acknowledges process and temporality and could have more works added at any time.

Poetry of Movement is by far the most impressive space in the center. It is packed with simple, elegant ideas that are well executed and don’t try to be anything other than good art. One corridor provides quality documentation of a number of winners of the prestigious Prix Ars Electronica, such as Dutch artist Theo Jansen’s lumbering, wind-powered, computer-designed skeletons, Strand Beasts. Another room is devoted to the marvellous robotic musical instrument Quartet by Jeff Lieberman and Dan Paluska, where 35 wine glasses make up the organ and 250,000 rubber balls fire at the marimba keys to perform a composition composed by a computer program from user input through a keyboard.

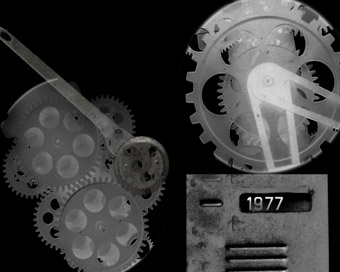

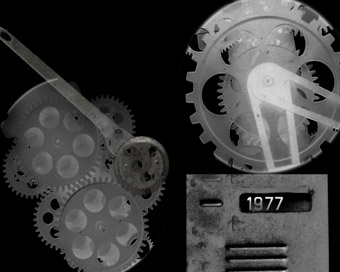

Arthur Ganson gets a whole room, which I was happy about even if it seems a little unbalanced. His Machine With Concrete is glorious, reminding us, in the midst of all the experimentation with cutting edge technology, that the world actually changes very, very slowly. The motor drives a series of gears and cogs, the last of which is fixed to a concrete block. The first rotation (in 1992) took about 14 seconds; the last one will take two trillion years.

This floor demonstrates that, in electronic arts, the kooky and low-fi can sit (if not comfortably, at least provocatively) next to the technologically seamless, and of the important aesthetic intersections of sound, kinetics and robotics.

Beyond being a museum, the Center is the permanent base for the Ars Electronica Festival. It is also home to Futurelab, a media art laboratory in which artists and scientists collaborate on the future, engineering exhibitions, designing installations and pursuing joint research ventures with universities and the private sector. This year’s festival (September 3-8) and the ongoing activities of Futurelab will be a test of the curatorial resilience of the new structure.

The Ars Electronica Center is indeed a landmark for the electronic arts, and for Linz itself, fortunately one that will live beyond the branding of the city as the 2009 European Capital of Culture. Like its predecessor, this museum is unique in the world as a showcase of the novel intersections of art and science. Some cynical Linz residents, however, call the center the “media arts brothel”—its curtain of lights are apparently very similar in hue and form, if not in scale, to a well-known red-light strip. With the hype of its opening in January and its slick presentation, the Ars Electronica Center begs the question, can the future be anything but overstated?

Ars Electronica Center, Linz, Austria, www.aec.at/center

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 31

© Alexandra Crosby; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

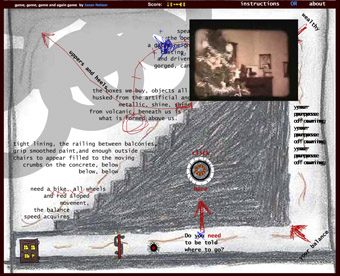

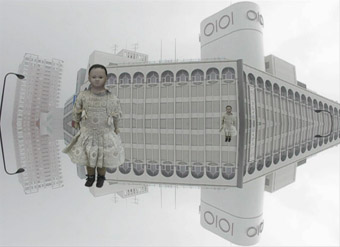

My Future is Not a Dream 01-08, 2006, Cao Fei

courtesy the artist and Lombard-Freid Projects

My Future is Not a Dream 01-08, 2006, Cao Fei

2009 SAW SOME REVISIONS TO THE ANNE LANDA AWARD EXHIBITION, ESTABLISHED IN 2004 AND NOW IN ITS THIRD INCARNATION: IT WAS THEMATISED (AROUND THE IDEA OF DOUBLES AND SPLIT IDENTITIES), IT WAS NO LONGER CURATED IN-HOUSE (GUEST CURATOR VICTORIA LYNN), BUT MORE SIGNIFICANTLY, IT WAS NO LONGER LIMITED TO AUSTRALIAN ARTISTS.

This may ultimately prove a positive move, providing more opportunities to view high quality video and ‘new’ media from around the world, and in general raising the bar and the profile of the exhibition. This year, however, the new format resulted in the work of local artists being overshadowed by the reach, ambition and emotional punch of their international counterparts’ projects.

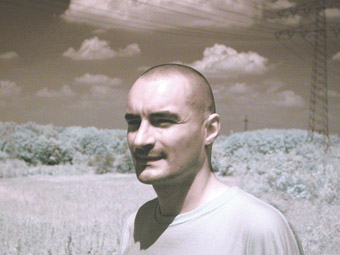

Take Whose Utopia? (2006), Cao Fei’s elegiac three-part video of factory life in China. The first part is an aesthetic paean to the processes of mass manufacture, with close-ups of seamless human/machine interaction that serves as a curious rebuttal to the industrial anomie and terminal mistiming comically captured in Chaplin’s Modern Times. But it is the second part that really captivates, as the workers of the first part emerge from anonymity as complex individuals enacting their fantasies amid the factory hardware. The workers dream of tutus and angel wings, electric guitars and graceful choreography, of deploying the fine motor skills required to sort light-bulb filaments instead to emulate the delicate gestures of a dying swan. The fantasies are not the stereotypical Western blue-collar dreams of wealth and status, love and sex. Rather the workers crave creative expression; their idealised figure is none other than ‘the artist’, specifically the performing artist.

The figure of the performing artist is also the focus of fantasy for the young Indonesian Smiths fans who answered Phil Collins’ call to participate in the third chapter of his globe-trotting The World Won’t Listen (2004-7), a video that documents karaoke versions of the British band’s classic album of 1986. I was initially skeptical of Collins’ project. The artist claims his gambit would not have worked if staged in “the first world circuits of pop and cultural industries” because he aimed to explore the reception of pop in places where it may have seemed as much “an imposition as a gift” (Collins cited in Catherine Fowler’s essay in Anne Landa catalogue, AGNSW, 2009). Yet I suspect the chosen settings of Guatemala, Turkey and Indonesia had more to do with the enduring allure of the exotic to the Western eye, and the promise of the simultaneously poignant and absurd slippages that can occur when a first world cultural form is appropriated by the geo-politically marginalized. And yet, the video manages to transcend its problematic politics through the utter conviction of the performers, some of whom emerge from their reverie as if from spiritual possession, physically trembling. Rather than evoking cultural ventriloquism, these devastatingly beautiful anthems of class and teenage alienation appear to belong to these singers. As they sing “Hang the blessed DJ, because the music that they constantly play, has nothing to say about my life” (from the song Panic), the cross-cultural implications may be complex, but the lyrics ring with Morrissey’s original meaning.

Nina, Me and Ricky Jay 2009, TV Moore, VHS & DVD transferred to DVD

courtesy the artist

Nina, Me and Ricky Jay 2009, TV Moore, VHS & DVD transferred to DVD

Music’s transformative power also subtends TV Moore’s award winning entry, a loose amalgam of sculptural installations—including a mirror ball, a TV/stereo cabinet and cymbals suspended from the ceiling—and videos on various screens that include the artist singing under hypnosis. This unedited evocation of the artist’s artificially induced altered states, with its at times ham-fisted symbolism and overloaded imagery, lacks the resonance and conceptual refinement of Moore’s earlier videos. While maximalism may have cost Moore, at the other end of the spectrum, the intuitive communication between twins is not enough to redeem the Mangano sisters’ video, Absence of Innocence (2008) from a certain lack of content.

Mari Velonaki’s Circle D: Fragile Balances, 2008, Circle E: Fragile Balance 2009, an attempt to challenge our expectations of what makes for a robot and a computer interface, through the design of blue-tooth enabled hand-held boxes that ‘write’ messages to each other, was compelling, but still in need of some development. In particular it would be fascinating to see a real time connection between messages scrawled by visitors and the screens on the boxes.

Finally, Lisa Reihana’s Digital Marae (2001 and 2007) offered a witty updating of the Maori ancestral meeting house. The artist replaced traditional elders with life-sized digital prints of ordinary Maori men, in the guise of figures from Maori legend, and traditional hand-crafted motifs with computer-generated animated patterns (Tukutuku: Terrain, 2009). The work has great aesthetic power, although its installation along the exhibition space’s external wall detracted from its intensity.

While Double Take may not shed much additional light on the experience of multiple personalities and split identities, through the works of Collins, Reihana and Cao Fei, in particular, it speaks poignantly about the intrinsic human need for creative expression. These works derive their power in large part from the artists deploying their own artistic agency to nurture that of the ostensibly dispossessed.

Double Take: Anne Landa Award for Video and New Media Art, artists Phil Collins, Cao Fei, Gabriella Mangano, Silvana Mangano, TV Moore, Lisa Reihana, Mari Velonaki, guest curator Victoria Lynn, Art Gallery of New South Wales, May 7-July 19

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 32

© Jacqueline Millner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Mellifera, Trish Adams, Andrew Burrell

MELLIFERA’S LAUNCH HAS TO BE THE ONLY OCCASION THAT AN EXHIBITION HAS BEEN OPENED BY RELEASING BEES IN A CROWDED ROOM. WELL, ALMOST BEES. CREATORS TRISH ADAMS AND ANDREW BURRELL CALL THE VIRTUAL LIFEFORMS THEY HAVE CREATED “MELLIFERA”, AFTER APIS MELLIFERA, THE EUROPEAN HONEY BEE, BUT THE CREATURES THEMSELVES SHARE AT MOST A FAMILY RESEMBLANCE WITH THEIR PHYSICAL COUSINS. THEY ARE, IN FACT, JUST ONE SPECIES IN THE SYNTHETIC ECOSYSTEM OF TERRA.MELLIFERA SET UP BY THE ARTISTS IN THE MULTI-USER ONLINE WORLD, SECOND LIFE.

The gallery walls are taken up with projections of what appears to be CCTV surveillance footage; but the terrain the cameras survey is from anywhere but the gallery surrounds. The valley outside is enclosed by precipitous cliffs and filled with strange polygonal flora in various states of growth and decay. A silent humanoid avatar flounces its antennae as it tends to the swarm of varicoloured insects the size of a human head. Across the gallery, a computer terminal invites you to pilot your own avatar through the imaginary valley. If you come hearing only of the bee-connection this is both more garish and more immersive than the average ecological simulation. In my email interview with them, the artists are quick to differentiate their work, as synthesisers of life, from the attempt to replicate the real:

Mellifera: “What we are creating is not a simulation but a space in its own right that has its own logic, in part inspired by some physical world ecosystems and the behaviour of Apis Mellifera… but is also very much its own space. A ‘simulation’ is replicating something else. This is something else.”

Be that as it may, the project claims multiple points of engagement with the physical honey bee. Firstly, the artists have researched “cognition, navigation and communications in the honey bee” at the Queensland Brain Institute, and mention it as an inspiration for the behaviour of their simulacra. More overt is the contemporary theme of ecological fragility evoked by bees, who are notoriously threatened worldwide.

It’s not apparent in the show at the gaffa gallery, but disaster looms for the mellifera as well. In the artists’ words: “The actual ‘terra mellifera’ in Second Life appears at first to be a pastoral paradise…however, whilst some [simulation states] will have an Elysian theme, others will involve dangerous invasions of pests which our virtual honeybees…will be unable to resist without the attention of ecologically aware avatars.” The artists, it seems, intend to subject their creatures to something analogous to the blight afflicting their real kindred.

Terra.mellifera is far from the first ecosystem in Second Life—and even bees seem to be common, occurring in two of the higher profile ones. Laukosargas Svarog’s famed Svarga’s simulation and Luciftias Neurocam’s Terminus have toyed with them. What’s different here (aside from an unspecified arsenal of gizmos and doohickeys which the artists hope to deploy in the later Brisbane show) is narrative. I’m reminded of Mitchell Whitelaw’s consideration of “critical generative systems”, and the implicit potential in these generative simulations to communicate “system stories” that explore possible worlds, systems whose underlying construction can create alternative perspectives on physical reality (“System Stories and Model Worlds: A Critical Approach to Generative Art” in Olga Goriunova ed, Readme 100: Temporary Software Art Factory, Norderstedt: BoD, Dec 2005, http://creative.canberra.edu.au/mitchell/papers/).

For Burrell and Adams, indeed, narrative and exploration are both critical. They are happy to disclose that their simulation is based largely around the venerable artificial life technique of agent-based modelling, that it contains birth, feeding and death and so on. But they are coy about the detail of the emergent foodweb, even to RealTime; that, they wish to leave to the experience of the visitor, at least for now. There is, apparently, a synthetic nature documentary in progress for the end of the project.

Mellifera, Trish Adams, Andrew Burrell

For now, the tribulations, and the gradual evolution and curation of the algorithms and interrelations of the mellifera are only visible to those spectators to the virtual component of the show, the denizens of Second Life. And it’s not just invasive pests, but the progress of the artwork itself: “As we introduce further code/behaviour/elements to the system, balance is lost, and sometimes it can take quite a while for equilibrium to return. Tiny changes to one piece of code can and do affect the whole system.” The experience of Mellifera, then, approximates a real eco-tourism project in a bona fide ecosystem, with all the responsibility and uncertainty that implies. This critical generative system explores the transience and delicacy of living systems—a noble sentiment.

My major qualm about the work is with the choice of medium of Second Life itself—if we can extract a detailed experience of the fragility of living systems from such a simulation, it is a lopsided fragility in that we are excluded. Second Life invites us to participate intimately as virtual avatars, and that participation is asymmetric; second-life avatars are solipsistically prime in the simulated world. These immortal, self-contained souls can create a balance of synthetic “nature” but cannot themselves be destroyed by it. Whereas the demise of the bees in reality seems likely to cost real human lives as our crops lose a key pollenating process. For us, the bees’ value is, tragically, far more than purely aesthetic, and organising to save the arbitrary danger to an artwork in the stead of a real ecosystem is quixotic.

The destinies of both real and virtual bees, however, and the artists’ handling of these difficulties, are all similarly undecided, and I recommend checking in on the progress of each. Terra.mellifera is ongoing in Second Life and will re-open in real life in Brisbane in August 2009 at The Block, QUT. Bee extinctions are continuing worldwide.

See also RT 84, p32, www.realtimearts.net/article/issue84/8951; and RT 87, p36; www.realtimearts.net/article/87/9181

Mellifera, artists Trish Adams, Andrew Burrell, gaffa gallery, Surry Hills, Sydney, April 16-21; The Block, August, QUT, Brisbane, http://mellifera.cc/

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 33

© Dan MacKinlay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

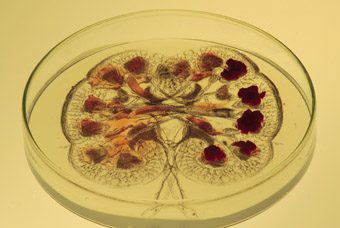

Niki Sperou, Man a Plant, giclee print (installation detail) Flinders Medical Centre, glass, plant, tissue culture, gel nutrient medium, drawing (2007)

IN HIS CATALOGUE ESSAY FOR BIOTECH ART REVISITED, MELENTIE PANDALOVSKI ASKS IF THE ASSIMILATION OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY HAS BECOME PART OF THE MENTAL EXPERIENCES OF THE GENERAL PUBLIC. THE DISTRIBUTION OF EXPLANATORY NOTES IN THE EXHIBITION SUGGESTS THAT THIS NEW FORM, BIOTECH ART, CANNOT YET BE UNDERSTOOD WITHOUT ASSISTANCE. THE ARTWORKS IN THE EXHIBITION ARE QUESTIONING: SIFTING THROUGH BODILY INTERACTIONS AT THE MICROSCOPIC LEVEL. ONLY ONE OF THE EIGHT WORKS (FOAM BY MAJA KUZMANOVIC AND NIK GAFFNEY) DOES NOT ENGAGE IN THE DISCOURSE ABOUT MINUTE CELLULAR ACTIVITY.

In NoArk I and II, Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr of the Tissue Culture and Art Project explore the taxonomical crisis that arises for life forms created through biotechnology. The work consists of two glass cases lit in dark red and blue. The first contains a boat/bag of mixed cells, the apparatus continuously rocking to keep them alive. The second contains, in order, taxidermied pig, rabbit, rat, mouse, crow, finch, fish, crustacean, mollusc, leech and a two-headed bird. These function as a Noah’s Ark-like collection of an evolutionary food chain, apart from the aberration of the two-headed bird, which acts as a kind of full stop. The juxtaposition of the objects in the two cases suggests that the suspended mass of cells in the first is a kind of scientifically created primordial soup that cannot be differentiated and thus classified.

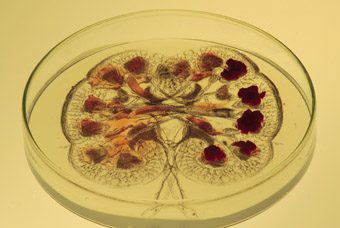

The notion of the undifferentiated is also found in Niki Sperou’s Man a Plant. Sperou continues her interest in chimera in this work with an exploration of a 1747 text, Man, a Machine, which stresses the similarities between humans and plants. Plants have the ability to rejuvenate themselves and humans are rapidly gaining this ability through research into the potential for stem cells to repair damaged human tissue. Sperou presents five Petri dishes each containing an anatomical drawing that has its plant-like aspects highlighted with growths of grape cells and nutrient gel medium. Each dish has condensation spots, which partially obscure our view of the contents, attesting to the blurring of life at the cellular level.

Andre Brodyk’s installation, Proto-animate19, also deploys the science of the Petri dish. The biohazard sign at the entrance to the installation highlights the artist’s use of e-coli in growing ‘junk’ or non-coding DNA. Interacting with this installation without consulting the accompanying notes can induce discomfort, even fear. The room is peppered with biohazard containers. Children’s chairs, clustered in the centre of the room, each contain a Petri dish growing a face. At first glance this is quite horrifying, lending a sinister aspect to the room. What has happened here? This reaction belies the subtlety of Brodyk’s work. The portraits of ‘John Does’ are grown from DNA not active in biological production, specifically the proteins associated with Alzheimer’s disease. These comprise a complex meditation on identity and the nature of bodies in this biotech era.

Bio Kino explore the exotic/erotics of the body on scientific display, by referencing early scientific film, particularly the work of Dr Eugene L Doyen, who toured his 1902 film of the surgical separation of conjoined twins in side-shows as a curiosity and an “educational tool.” Bio Kino have miniaturised digital film to 500 microns, about half a millimetre, and projected them onto living cells. This living screen reacts and deteriorates, distorting the images. The resulting Striptease of the Siamese is a strangely erotic film of conjoined twins revelling in their dance together. The process by which the work has been made is just as disturbing and fascinating as the subject matter.

Changing Fates_matrilineal is constructed by an equally fascinating process. Trish Adams cultured adult stem cells from her own blood and used a chemical formula to change them into cardiac cells. The cardiac cells then clustered and began to beat. The DVD of this work contains images of these cells intertwined with the writing and photographs of the artist’s grandmother, accompanied by a sound track of breathing, soft whistling and a heart beating. In the explanatory notes the artist discusses the intertwining of the emotional and the biological, and the ephemeral nature of life. Equally the work suggests cellular sentience and it is hard not to attribute some kind of feeling to the heart cells beating together and a kind of sadness for their limited lives.

On entering Nanoessence, a collaboration between Paul Thomas and Kevin Raxworthy, you are instructed to breathe onto the model of a skin cell which is then projected onto a wall. The minute changes that the breath produces register on an airy landscape. The sign asking the viewer to interface with the work concludes with “Do not touch”, immediately bringing to mind questions of what touch is, body boundaries and how much of the body spreads into the atmosphere in the act of breathing. The world is, after all, littered with dead skin cells. The artists question the ocular-centric world of scientific research through seeking to collect data through touch, involving a fuzzy logic of shifting boundaries and not always containable movement.

Micro ‘be’ Fermented Fashion by Gary Cass and Donna Franklin and BioHome: The Chromosome Knitting Project by Catherine Fargher are perhaps the least subtle and most overtly confronting works of the exhibition. Cass and Franklin developed living garments using the cotton-like cells that are a by-product of the fermentation of wine to vinegar. The resulting clothes are dark red, wet and clotted looking. They function as a kind of bloody second skin on the bodies of the models. One photograph shows gruesome drips seeping down the back of the model. Playing with the world of fashion and the cult of youth this work introduces clothing that will age with you. As the accompanying text proclaims, a future which includes the monstrous will be found attractive by some, and not by others.

The soothing advertising-styled voice of the DVD of BioHomes: The Chromosome Knitting Project (Catherine Fargher, Terumi Narushima) offers a welcome that dominates the entire gallery. Its utopian, sci-fi tones, promising a brave new world, at first distract from the more complex, intricate works in the exhibition. The installation focuses on intensifying viewer discomfort about biotech products in the home. Unease is amplified by uncertainty; signs suggest viewer interaction: What am I touching? Breathing? As with Brodyk’s installation, Proto-animate19, the shock value of this installation obscures some of its subtleties. But curator Melentie Pandalovski highlights the importance of a visceral response to biotech arts and the physical unease triggered by BioHomes is testament to this.

Andre Brodyk writes of space being activated by different viewers as they enter into it, temporarily combining and recombining with other spatial elements. This Deleuzian notion is active in Biotech Arts Revisited as viewers become increasingly aware of their bodies, internally and externally. The visceral discomfort and fascination produced by the exhibition’s focus on the microscopic and the cellular is evidence of the continual revisions inherent in our relationship with our own and others’ bodies, as borders shift with each new technological and scientific development. The subtler aesthetic experiences of the works in Biotech Art Revisited suggests that the experience does not always have to be ugly.

Biotech Art Revisited, curator Melentie Pandalovski, Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, April 9-May 2, www.eaf.asn.au/2009/biotech09.html

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 34

© Kirsty Darlaston; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

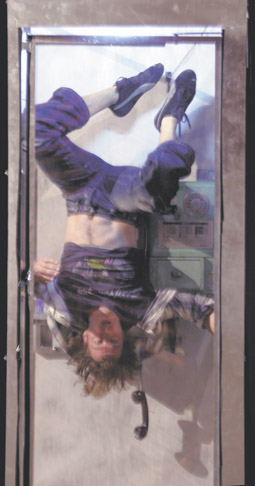

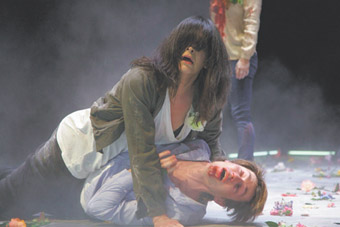

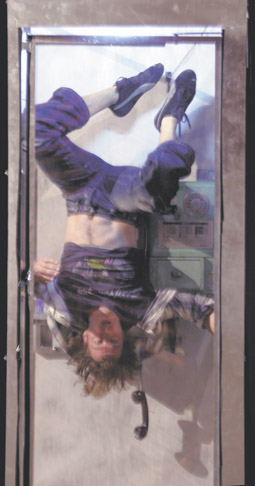

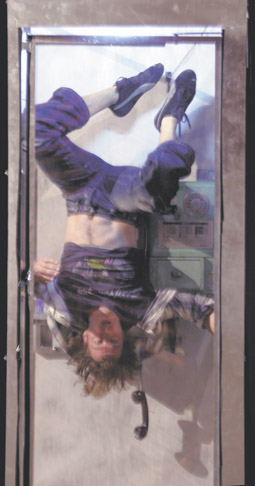

Brooke Stamp, Luke George, Miracle

photo Jeff Busby

Brooke Stamp, Luke George, Miracle

I LAST MET PHILLIP ADAMS, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF BALLETLAB, FOR REALTIME PRIOR TO THE PREMIERE OF HIS AXEMAN LULLABY MID-2008 (RT86, P32). AT THAT TIME, ADAMS WAS OPTIMISTIC ABOUT THE COMPANY AND ITS PLACE IN THE AUSTRALIAN DANCE LANDSCAPE. DESPITE THE CRITICAL SUCCESS OF THIS WORK (IT JUST WON A COUPLE OF GREEN ROOM AWARDS FOR CHOREOGRAPHY AND FOR COMPOSITION) AND A CONFIDENCE-BOOSTING SHOWCASE AT THE CINARS INTERNATIONAL ARTS MARKET IN LATE 2008, ADAMS HAS BEEN SOBERED BY FUNDING REVERSALS FOR HIS COMPANY.

This meeting is about Miracle, the new full evening dance production to premiere at Melbourne’s Meat Market in July. It is also about Amplification, the piece that launched BalletLab in 1999 and which will be restaged at the Australian Dance Awards, in June, at Melbourne’s Arts Centre.

These two presentations are gratifying for Adams, as they bookend a decade of vigorous experimentation with form and content. The early piece was an apocalyptic response to the violence of the 20th century as it came to its close. It featured a score and choreography so ferocious it made audiences and critics alike sit up and notice the new company. For Adams Miracle is a “sequel to Amplification.”

Miracle’s starting point is the search for transcendence which follows the car crash of Amplification. Adams sees contemporary humanity pursuing the miraculous in order to escape disillusionment with the material world. He finds his evidence in the current resurgence of religious fanaticism, cults and mass market spirituality.

A New York residency at EMPAC (Experimental Media and Performing Arts Centre, Rensselaer Polytechnic) gave Adams the opportunity to experiment with the clash of sound and choreography which he envisioned as creating the hallucinatory mood for the piece. He took four of his regular dancers—Luke George, Brooke Stamp, Clair Peters, Kyle Kremerskothen—as well as key collaborator and composer, David Chisholm, and new recruit, sound artist Myles Mumford, for a four week stay at this generously resourced arts centre [see RT 89, p24]. There Chisholm and Mumford recorded live sound from the dancers in rehearsal as well as a range of composed material with US instrumental group, ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble).

This material will form the body of the design for Miracle, as Adams dispenses with set and works with a very limited lighting palette by Paul Jackson. Adams is not au fait with the fine points of the technology the composers are using but he is confident that the experiments they undertook at EMPAC with “handheld amplifying megaphones and a surround sound speaker orchestra” will create the effect of “a triumphant onslaught of hysteria.” Adams says, ”My fascination with the epiphany is performed against repetitive mantra, phrase and hymn-like voices. It is an examination of false hopes and religious stereotypes that promise a new beginning.” Chisholm and Mumford will perform the electronic score live, modifying it subtly to each performance. Adams talks about a technological illusion of levitation created through the sound of one hundred harmonicas played by the dancers, amplified and looped to create an almost intolerable din, instigating a prolonged state of suspension like a universal pause.

This sense of repulsion is one that Adams also aims for in the choreography. He told me about an outdoor try-out in Hobart which was quickly shut down. Adams’ desire to, “choreograph the frantic spectacle of a real life miracle” was too much for his Tasmanian audience. The state of desperation achieved by his dancers running raggedly across the stage to the point of exhaustion was apparently beyond the pale. “I have situated the performers sometimes as heavenly bodies, sometimes from mythology and above all I am trying to remove [a sense of ordinary humanity] from the structure of the performance.”

For Adams, Miracle is another step in the direction of visual art performance installation. Despite his adherence to the proscenium and his engagement of key collaborators from the performing arts, Adams is most stimulated by the possibilities for BalletLab outside the theatrical context.

Miracle will be programmed as part of Melbourne’s State of Design Festival and Adams is proud to state that director Fleur Watson was very taken by the relationship between the production and the “Sampling the Future” theme of her festival. The fact that the costumes for Miracle will be designed by Melbourne fashion designer of the moment, Toni Maticevski, could also have played a role in her decision to include BalletLab as the sole performing arts company in the program.

This new presenting partnership is an example of Adams’ entrepreneurial zeal and faith in the role of BalletLab as provocateur to the contemporary dance status quo. Adams talks with rhetorical glibness about “new audiences, new programming formats and art-form innovation” as the markers of his 10-year-old company. He may be turned off by the reductive process of business planning which won him so little funding reward last year, but he has clearly found a strategic position for which he will fight.

In 2010 BalletLab will undertake “a structured studio exchange” with the Australian Ballet as part of the Australia Council’s Interconnections project. Adams says that for both organisations “the project forges a new creative relationship to investigate different types of choreography that redefine dance genres, whilst promoting resource sharing between the small to medium-sized and the major performing arts sectors. Our program is a platform for BalletLab to realise its ambition to implement the Lab component of the company. Our collaboration will invoke a transformative creative experience between a progressive language in contemporary dance and classical technique. This creative dialogue will also be reconfigured through artistic collaborative experimentation in design and music composition.”

The Australian Ballet partnership, a major commission for 2010 from the Museum of Old and New Art in Tasmania and the prospect of international touring for Brindabella (RT83, p43) and Miracle are all keeping Phillip Adams upbeat in downbeat times.

BalletLab, Miracle, Arts House Meat Market, Melbourne, July 15-19, www.balletlab.com; State of Design Festival, July 15-25,www.stateofdesign.com.au

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 36

© Sophie Travers; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion

photo Alastair Muir

Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion

A GEOMETRICAL APPARATUS TAPERING OFF INTO BENCHES, SCREENS AND AN IMMACULATE LINE-UP OF ELECTRIC GUITARS IMMEDIATELY CONVEY A SENSE OF A LABORATORY SCRUBBED IN READINESS FOR THE NEXT EXPERIMENT. THERE IS EVEN SATISFACTION IMAGINING WHAT CHEMISTRY THOSE SHINY METAPHORICAL INSTRUMENTS MIGHT CHARGE INTO THE THEATRICAL SPACE. BY CONTRAST, TWO WOODEN CHAIRS PLACED IN PICA’S UNADORNED BLACK BOX PROMISE LITTLE OTHER THAN A CONVERSATION. WHAT TRANSPIRES IN THOSE TWO DISPARATE SETTINGS THROWS CONCEPTS OF SCIENTIFIC EXPERIMENTATION INTO DISARRAY AND SCORES ANOTHER POINT FOR THE POTENCY OF UNPREDICTABLE SIMPLICITY.

There is no direct correspondence between Buzz Dance Theatre’s Depth Charge and Strut Dance’s presentation of Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion’s The Trilogy, other than being two dance productions which surfaced in the same time-frame and yet their coincidence raises questions about performance and transformation. Whereas Depth Charge announces itself with a bionic forearm, imaging “a future where dance ensembles are genetically engineered”, The Trilogy relies on its UK origins, a few phrases from ‘spellbound’ critics and, for a select group of aficionados, anticipation of an actual encounter with two men who have honed choreographic formalities down to two sets of hands. With Buzz’s commitment to creating performances and developmental dance opportunities for young people, explorations into bioethical issues arising when science breaches nature’s laws appear apt and timely. Likewise Burrows and Fargion’s radical movement palette concurs with Strut’s objective to expose the local community to choreographic diversity.

Depth Charge, Buzz Dance

photo by Loft Group

Depth Charge, Buzz Dance

The boldness of Depth Charge falters at its inception. A mild mannered musician, Leon Ewing, enters the ordered laboratory, takes the first guitar from the board and sings. Screen codes appear and fade into supine dancers moving like their live counterparts on stage. After the fact of ‘creation’, genetically engineered dance creatures take over. Could it be that the collaborative team, led by artistic director Felicity Bott, intended to upend the obsessive behaviour of those legendary megalomaniacs, Drs Coppelius and Frankenstein, to suggest that birth transgressions now reside in computer nerds’ fingertips? Desires to create the perfect loved one flicker as does a utopian notion of ‘creativity,’ but the resultant cyborgs of flawless skill do not convey any of the conflict of Coppelia’s soullessness nor of the tragic designation of Frankenstein’s unloved monster.

Even the promising sequence of computerised joint manipulation played out between screen imagery and performers becomes aesthetically normalised, voided of the computational crunching that arguably would be required to tease a forearm’s complex articulation. Explosive rock dissolves too quickly into harmonious scores to intimate gravel-like irruptions and the dancers’ virtuosic performances suggest other than fearsome bionic creatures defying ethical parameters of humanness. Admittedly, Depth Charge is a work-in-progress, still in a stage of genesis wherein the main thrust of the work has yet to find its shape of impact. Its multiple influences and modes, at this point, evade cohesion.

The Trilogy, alternatively, enacts a single idea—relations between music and dance—through two compositors bent on teasing out eye-ear interconnections with distilled detail and glissandos of playful daring. Ironically, this gentle work of art exemplifies scientific rigour.

Bearing imprints of postmodern minimalists, the dance of Ann Teresa de Keersmaeker (Company Rosas) and the music of Philip Glass and Steve Reich, this experiment in performance makes gesture vibrate and sound twist and skip in Möbius-strip loops where the distinctiveness of one expressive form slides over into the textures of the other. Viewed from another set of coordinates, the two mature spirits (performers/scientists) map out sketches of a Wagnerian total theatre. This appealing small talk theatre contains all dimensions: the tension, intensity, amazement and incisive timing of a spectacle seen through the key-hole of human intimacy. On the other hand, Burrows and Fargion simply engage in a conversation that begins and ends on chairs. That’s where the bald pates’ acrobatics lie, in the flips, crossovers and slightly competitive actions while sitting.

Both Sitting Duet opens with the performers placing their scores on the floor, signalling the eloquent dance of palms, wrists, fingers, elbows, shoulders and head which unfolds until upper torsos, whipping tongues and side-glances are all involved in the rhythmic interplay. Parodic classical ballet moments splinter into the exchange, with Burrows using the encoded position of the arms in counterpoint with Fargion’s four metre bar scansion. Mathematical in-jokes elucidate the scientific scrutiny of the complex music-dance relationship. The quips are deliciously fast, resounding against a Cage-like silence until the coda is punctuated with erect moments of stamping like some ironic operatic crescendo which dissipates back into the sitting.

A roar from Fargion describing a downward-bending walk from Burrows launches The Quiet Dance. Reciprocation comes with Burrow’s ‘shussing’ the same phrase enacted by Fargion and so the permutations spill sonically, rhythmically and spatially to enunciate and amplify the rifts initiated in the ‘sitting’ gestural animations. Music is harnessed to the dance, made literal by the glanced partnering conventions where Burrow leads Fargion physically across the space.

Speaking Dance reverts in some ways to known Dadaist experiments with word, sound and rhythm and, though cleverly exploiting innuendoes of ‘left’, ‘right’, ‘stop’, and ‘come on’, the effect separates music and dance, dislocating Burrows’ beautifully executed movement from Fargion’s equally exquisite Italian folk singing. Is this a mirror-image of Sitting’s silent dance where sound becomes the dominant motif, or an expression of dance’s freedom from musical enslavement? Text, recorded music and harmonicas, while treated playfully, break the spell of the intimacy between these two nomadic scientists of the imagination.

Science and art share explanatory functions in human affairs. Over time, their divergences have become ostensibly acute with science’s emphasis on fact and art’s claim to imaginative capacities. Burrows and Fargion’s unorthodox, yet meticulously formal experiment into the facts of sound and movement questions such deviations, asking, moreover, why knowledge needs to be compartmentalised. Their Trilogy initiates questions for the future when two middle-aged men may encounter younger but, possibly, less informed cyborgs.

STRUT dance: Jonathan Burrows, Matteo Fargion, The Trilogy—Both Sitting Duet, The Quiet Dance and Speaking Dance; PICA, April 26; Buzz Dance Theatre, Depth Charge: Dance meets science with explosive force, Playhouse Theatre, Perth, May 6-16

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 37

© Maggi Phillips; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Paul Romano, Luke Hickmott, The weight of the thing left its mark

photo Dianne Reid

Paul Romano, Luke Hickmott, The weight of the thing left its mark

THE WEIGHT OF THE THING LEFT ITS MARK IS ABOUT SUBJECTS AND OBJECTS. THE OBJECTS ARE DOMESTIC IN SCALE, HOUSEHOLD ITEMS TAKEN FROM A DRAWER OR CUPBOARD. THE SUBJECTS ARE HUMAN, TWO OF EACH KIND. THIS IS AN IMPROVISED WORK, THAT IS, AN IMPROVISATION WITHIN A FRAME OR SERIES OF FRAMES. THE DOMESTIC SETTING OFFERS ONE SUCH FRAME. IT HELPS US LOOK AT THE MEN AND WOMEN AS IN SOME KIND OF RELATIONSHIP.

The breadth of the upstairs theatre at Dancehouse is warmed by a soft, golden light. It creates a panoramic kitchen scene, maybe in a farm. All begin seated around the table, alongside a large pile of cutlery. We wait. The waiting suggests a degree of flexibility. Perhaps the performers do not know who will begin or how. Is there a reluctance to start? The responsibility for beginning can be felt even before the dancing occurs. Once begun, the flow of the movement then takes over and the burden lessens. The utensils help. Small confined moves slowly build towards a crescendo of sound. The cutlery is hard, almost violent.

One by one the dancers rise to perform. Since most of them enter through a solo improvisation, the first kind of relationship is to the self as seen by others. This is how the solos looked to me. The rhythm of each improvisation was articulated into chunks, where each chunk constituted a move. The mind of the performer appeared to demand the repeated influx of ‘new’ movements. A succession of moves ensued where much attention was given to the joints of the limbs. These broke up the flow of movement but seemed to offer the reassurance of a certain kind of focus and logic. It is as if the bones of the body and their pivotal moments —knees, elbows, hip joints, ankles, neck—were the fabric of the movement.

Dancers choose between these dominating possibilities. One dancer flings her body from an anchored centre. Another falls into the vortex of his joints. Finally, one dancer breaks this staccato rhythm with a more flowing approach. It is harder to discern the percussive rhythm of conscious choice (move-move-move-move) in this more durational solo.

The burden of ‘creation’ implicit in improvisation seems to be lessened when the responsibility is shared. The duets in The Weight… were more than dialogue. They created feelings and atmospheres which belonged to a new unison, one formed between and across the two bodies. The girl-girl and boy-boy duets were distinctive and interesting. One of the dancers (Paul Romano) performed an extended dance with a spade, working with and responding to its weight with great clarity. Other objects were also brought into relation to the dancing—the cutlery, knives, a pitchfork, pouring grain from a sack.

There were times when the objects seemed to take on the responsibility of choice in this work, where they had more agency than the performers. Is this the weight of the object? If so, then there is a perceptible oscillation in The Weight of the Thing Left its Mark between the conscious agency of the dancer and the potential of the object to assume that agency. And the dancing is to be found in between.

The Weight of the Thing Left its Mark, director, choreographer Shaun McLeod, performers, co-choreographers Olivia Millard, Paul Romano, Sophia Cowen, Luke Hickmott, sound design Madeleine Flynn, Tim Humphrey, lighting Daniel Holden; Dancehouse, Melbourne, April 23-26

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 38

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tess de Quincey, Ghost Quarters

photo Mayu Kanamori

Tess de Quincey, Ghost Quarters

WATCHING DE QUINCEY CO’S GHOST QUARTERS IS LIKE WITNESSING THE GROWTH OF A FOREIGN ORGANISM, ONE THAT TRIGGERS IN EQUAL PARTS CURIOSITY AND ANXIETY. NOT SURPRISINGLY IT’S AN APTLY GOTHIC EXPERIENCE. THOMAS DE QUINCEY (1785-1859), THE ESSAYIST WHOSE WRITINGS INSPIRED THIS WORK, NUMBERED AMONG HIS ENGLISH ELDERS AND PEERS THE PIONEERS OF THE LITERARY GOTHIC. ADDING ANOTHER LAYER OF EERINESS IS THE POSSIBILITY THAT TESS DE QUINCEY, HERE EMBODYING, OR SHOULD I SUGGEST CHANNELLING (IF IN NO WAY ENACTING) THE GREAT MAN, IS POSSIBLY ONE OF HIS DESCENDANTS.

Ghost Quarters evolves like an expanding, multiplying cell. The audience, embraced by surround sound, sits on either side of a large installation, its long strips of translucent material rising high into the ceiling. Projected onto and through them are immersive images created by Sam James that evoke the now dream-like environments—unkempt nature, a haunting household with ornate chairs and chandeliers, a huge industrial space (using CarriageWorks itself)— the writer once travelled through and by which he was psychologically shaped.

De Quincey is curled on the floor, quivering into life, or is it possession? As she rises to engage with this strange space, in movements that seem to alternate tremulously between claustro- and agoraphobia, so do images, visual and aural, begin to consume us. Shimmering grass reappears, grown spookily tall, an arched window appears on high, beckoning but threatening as the relentless chatter of the sound score suggests murder.

Later De Quincey grapples with the hung material, pulling it after her as if to take control of the writer’s disturbed vision (he wrote The Confessions of an Opium Addict), then ventures out towards the audience, almost as if seeing us, pushing at some inner boundary. Finally, she exits through a huge creaking CarriageWorks door to the outside world, as if perhaps released.

If Ghost Quarters is an intriguing work replete with moments of palpable tension and sublime beauty, it is also a work not fully grown. De Quincey is, as ever, fascinating to watch, but my engagement with Ghost Quarters was disturbed by the chattering sound score, a word salad reminiscent of experimental radio works of recent decades. The credits attribute the vocals to Amanda Stewart, but there’s an altogether odd mix of voices, accents and vocal styles, while the setting for Stewart’s own delivery is pitched so low as to make her often unintelligible.

Jane Goodall’s text, drawn from Thomas de Quincey’s writings, is interesting in itself, when you can pick it out from the echoing repetitions and layerings (presumably intended to suggest that he ‘heard voices’), but there doesn’t seem to be a lot to it. Each of its several key passages relate to moments in the essayist’s life, to events, psychological states and to ideas about nature and murder, but they are slender, leaving you greedy for more. No amount of sound manipulation and design can compensate. Why not something more from Thomas, just to make a little more sense of the man and his condition? This need not be a surrender to the conventions of documentary or narrative. And as there’s one Tess embodying Thomas, why not then one voice, Stewart’s? Ghost Quarters is a fascinating work that has room to grow, to become an organism both more spacious and dense.

–

De Quincey Co, Ghost Quarters, first dream of The Opium Confessions, dance Tess de Quincey, script Jane Goodall, vocals Amanda Stewart, video Sam James, sound Ian Stevenson, lighting Travis Hodgson, CarriageWorks, May 6-10

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 38

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

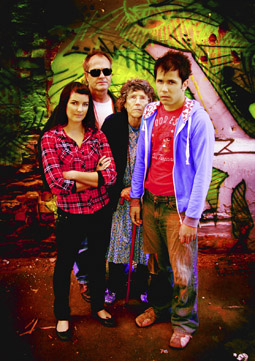

Shelly Lauman, Katherine Tonkin, Anne-Louise Sarks, 3XSisters, Hayloft Project

photo Jeff Busby

Shelly Lauman, Katherine Tonkin, Anne-Louise Sarks, 3XSisters, Hayloft Project

THE APPARENT DEMISE OF THE CLASSIC PLAY IS A BIT OF A STALE POINT THESE DAYS. THOUGH THERE ARE STILL INTERMITTENT RUMBLINGS ABOUT THE INCREASING DOMINANCE OF NON-TEXT-BASED THEATRE, A QUICK LOOK AROUND WILL PUT THE ARGUMENT TO BED. EVEN MALTHOUSE THEATRE’S MICHAEL KANTOR—ONE OF THE MOST VOCAL PROPONENTS OF COLLABORATIVE, IRREVERENT THEATREMAKING—REGULARLY TURNS TO THE OLD GREATS FOR MATERIAL. THE INDIE SECTOR, TOO, IS POPULATED BY CANONICAL TITLES. A BRIEF SURVEY OF SOME RECENT ADAPTATIONS DOESN’T EXACTLY ARGUE WELL FOR THIS FAITH IN THEIR ENDURING VALUE, HOWEVER.

The Hayloft Project’s ambitious take on Chekhov’s Three Sisters—here renamed 3xSisters—is the first case in point. Three directors took randomly selected chunks of the original and independently produced their own bold reimaginings employing the same cast. Simon Stone took a fairly modernist, faithful approach. Relocating the opening and closing parts of the play to a brightly lit waiting room, he confidently played around with the setting and structure of the work while remaining true to its dramatic core. This is consistent with Stone’s past Hayloft efforts such as Spring Awakening and Platonov, both excellent productions that successfully reshaped classic texts to revitalise their essence without bastardising their original spirit.

Benedict Hardie’s sequences employed meta-theatrical devices to denaturalise Stone’s preceding scenes. Suddenly we were watching a group of actors rehearse and discuss the play, with occasional directorial interruption and character swapping. Though more formally innovative, it was never clear what this distancing was supposed to achieve, and Chekhov’s narrative certainly disappeared in the controlled chaos of rehearsed spontaneity. I suppose it’s a nice irony that the script faded away once it was being held in hand onstage by the performers.

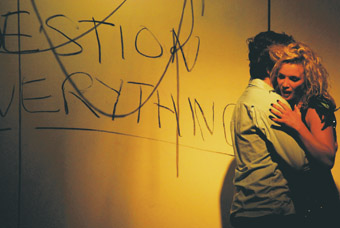

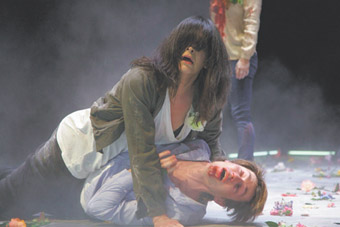

Mark Winter’s central section of the play was the most confounding, seemingly dispensing with the text almost entirely and injecting an array of intertexts which seemed almost randomly selected. Mild jabs at the Australian performance landscape—an emergency theatre kit posted by Benedict Andrews, for instance—collided with entire slabs of dialogue lifted from Scorsese’s Taxi Driver; bloody violence was dispensed with casual abandon; characters lost any sense of verisimilitude as they became mere velocities, effects without cause. It’s the kind of anti-theatre that Black Lung, of whom Winter is a member, do so well. Here, not so much.

The question which underscores 3xSisters is—why? Why adapt Chekhov at all? The play itself seemed of little interest to the directors, acting rather as a hook upon which to hang a series of formal or stylistic costume changes. This might be a worthy artistic choice if any of these forms were advanced in productive new ways, but as theatre, meta-theatre or anti-theatre, 3xSisters never quite goes beyond the level of experiment.

I’m all for irreverence, though. Caryl Churchill’s 2005 translation and adaptation of Strindberg’s A Dream Play radically reworked the original, paring back its bloated mass to produce a tighter, more aerodynamic thing. This is commendable, since Strindberg’s play is of much historical interest but pretty dusty looking these days. The 1901 text may have been a pioneering work of non-rational, non-naturalistic theatre, but it’s naïve to try to recreate that avant-garde experience in an age where surrealism can be found in a Cadbury’s chocolate commercial.

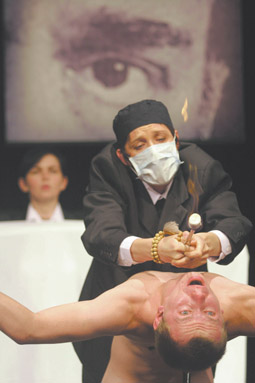

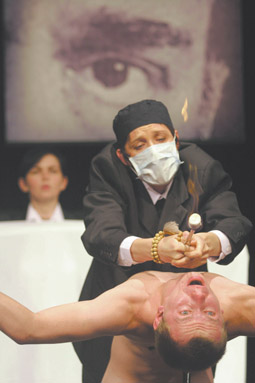

Michael Finney, Meredith Penman, A Dream Play, IGNITE

photo Chris Nash

Michael Finney, Meredith Penman, A Dream Play, IGNITE

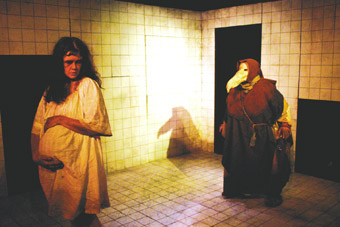

Ignite Theatre’s production of A Dream Play managed to enable a rewarding experience despite the limitations of its source. This was mostly due to Churchill’s text and strong, energetic performances from a group of young-ish but well-experienced actors. Meredith Penman delivered a dynamic, visceral protagonist who held together the disparate, illogical scenes which make up the play; her fellow cast-members each took on a variety of roles and managed to make each distinct and, mostly, attention-grabbing. The only hobbled point of the work is the lengthy sequences involving the tortured Writer, a partial stand-in for Strindberg himself. Nobody needs to see the old cliché of an angst-riddled writer wrestling with the meaning of the universe; let the work itself do that job. Ignite and director Olivia Allen do the best they can with this little hiccup, though, and at least the rattling pace of the production doesn’t allow it to dwell too long on such sludgy moments.

If there’s one writer who epitomises that tortured cliché, it’s good ol’ Kafka. A figure whose biography is as fascinating as his writings, Kafka is as good as his reputation suggests. Many of his stories feature the image of the message which can never reach its recipient or the seeker forever delayed from reaching his destination; apt metaphors for the meanings of his elusive works themselves, which constantly retreat from our interpretive grasp without ever fully escaping our hopeful advances. If you can’t tell, I really like Kafka. I also really like monkeys, but the recent Malthouse Theatre presentation of UK performer Kathryn Hunter’s acclaimed turn as Kafka’s Monkey, touring nationally, disappointed on both fronts.

The piece is a solo adaptation of Kafka’s short story “A Report to an Academy.” A monkey is shot by hunters on the coast of Africa and transported to civilised Europe, learning along the way to ape the actions and speech of his masters in order to survive. He eventually chooses a life on the variety stage—the zoo being his only other option—and suppresses all traces of his earlier existence. It’s a tiny work but there’s a lot going on beyond this quick synopsis. The story raises thorny questions of the naturalness of identity, the fluidity of performance and countless connotations of otherness and the violence of acculturation. All of these are present to a degree in Hunter’s performance, but what is lacking is a real sense of the monstrous role of language underscoring Kafka’s story.

In A Report to an Academy, language embeds itself as a kind of cage, imprisoning the narrator. The ironic, coolly rendered prose is itself a problem, making evident the forced abstention of any actual “monkeyness” from its speaker. He is an exile from himself, a refugee who has built a raft of words. And, being a short story, words are all we have of his slippery existence.

The problem in performing such a text should be obvious—physically embodying a character who is more of an absent haunting than an authentic-seeming presence. And Hunter, under the direction of Walter Meierjohann, is a compelling physical performer. But her success is in imitating, even caricaturing, the loping, wide-eyed demeanour of a monkey. Her monkey is all presence, often stepping down into the audience to touch her spectators, or offer a banana, pick at fleas in their hair—solid theatre tricks that seem entirely misplaced here. Though she is clad in the stiff attire of a tuxedo and speaks of her assimilation into human society, this is an incarnation that seems intent on showing us a primate, rather than mourning its disappearance.

Kafka’s Monkey is a very watchable theatre, enjoyable even, but it’s not Kafka. And while 3xSisters barely attempts to be Chekhov, and A Dream Play displays an admirable distance from Strindberg, the more polished, expertly executed Kafka’s Monkey finally seems the least comprehending of its source.

The Hayloft Project, 3xSisters, after Three Sisters by Anton Chekhov, directors Simon Stone, Benedict Hardie, Mark Winter, design Claude Marcos, lighting Danny Pettingill, performers Gareth Davies, Angus Grant, Thomas Henning, Joshua Hewitt, Shelly Lauman, Eryn Jean Norvill, Anne-Louise Sarks, Katherine Tonkin, Tom Wren; Arts House Meat Market, April 24-May 10; Ignite Theatre, A Dream Play, after A Dream Play by August Strindberg, adapted by Caryl Churchill, director Olivia Allen, sound design Russel Goldsmith, lighting Angela Cole, set & costumes Kat Chan, Eugyeene Teh, performers Gary Abrahams, Meredith Penman, Mark Tregonning, Michael Finney, Heath Miller, Kate Gregory, Nicholas Dubberley, Hannah Norris, Karen Roberts; Bella Union, Trades Hall, May 5-17; Young Vic, Kafka’s Monkey, after “A Report to An Academy” by Franz Kafka, director Walter Meierjohann, adapted by Colin Teevan, performer Kathryn Hunter, set Steffi Wurster, costume Richard Hudson, lighting Mike Gunning, sound & music Nikola Kodjabashia; Malthouse, Melbourne, April 28-May 9

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 40

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Kelly Doley, Six Minute Soul Mate Brown Council

photo Alice Gage

Kelly Doley, Six Minute Soul Mate Brown Council

SYDNEY PERFORMANCE GROUP BROWN COUNCIL ARE DOING PRETTY WELL FOR THEMSELVES. THEIR FIRST FEATURE-LENGTH PERFORMANCE, SIX MINUTE SOUL MATE, A DARKLY COMEDIC LOOK AT MODERN LOVE, RECENTLY WON THEM AND THEIR PRESENTING PARTNER, VITALSTATISTIX, THE ADELAIDE FRINGE AWARD FOR BEST THEATRE PRODUCTION. THIS MAY SEEM A TOUCH IRONIC FOR THOSE FAMILIAR WITH THE GROUP’S WORK, WHICH SERVES AS A CHALLENGE TO CONVENTIONAL NOTIONS OF THEATRE. BROWN COUNCIL’S WORK REVEALS A VERSATILITY THAT SEES THEM WORKING ACROSS GALLERY AND THEATRE SPACES, AS WELL AS THE MEDIUMS OF LIVE PERFORMANCE AND VIDEO ART.

As performers, Brown Council embrace an over-the-top theatricality but with a consistent sensitivity towards the audience’s experience. I saw Six Minute Soul Mate, a show for 12 people per 55-minute performance at Next Wave 2008 in Melbourne and the 2009 Imperial Panda Festival in Sydney—two very different experiences.

A glass of bubbly and friendly greetings upon entry are a nice prelude to seating instructions, “bunch up, get to know one another”, that come from our guide and chaperone for the evening, the Love Bear. Think Cupid with attitude, an oversized bear head and a stopwatch instead of a bow and arrow. Speed dating is the premise for Six Minute Soul Mate, the conventions of this modern phenomenon adopted to introduce the audience to three obviously desperate singles. Blue Lady, Pink Lady and Allen are played interchangeably by the members of Brown Council—Fran Barrett, Kate Blackmore, Kelly Doley and Di Smith. Meanwhile, cheesy love-pop asserts its irritating presence. Berlin’s “Take My Breath Away” is looping in my head, still, as I write this.

We meet the characters three times each in a series of six-minute exchanges, each signalling a further descent into the grotesquerie and folly of wretched singledom and of romance gone wrong. Desperation is taken to a new level when Pink Lady (Doley) stands in front of us pleading for someone, anyone, to kiss her. This night a willing audience member volunteers. When I saw the show in Melbourne, she stood in the dark pleading for four minutes to no avail.

Brown Council parade the tired symbols of romantic idealism in this critique of modern dating services—enterprises that exploit loneliness and desire, offering a ‘quick fix’ to lonely hearts. “My ideas of romance are simple”, sighs the Blue Lady, “flowers just for no reason, trails of rose petals leading to the bedroom.” She is perched in front of a painted scene of a snow-capped winter wonderland, framed as if seen through a heart shaped window. The backdrop suggests the artifice and emptiness of such pre-packaged romantic sentiments.

The loose script aims straight for parody, immediately establishing the comic tone that prevails for most of the show. Audience members are invited into cumbersome interactions with the characters. For six minutes Di Smith as Pink Lady tries to pickup an audience member, who happens tonight to be Charlie Garber, another performer whose group, Pig Island, are also featured in the Imperial Panda Festival. “What’s your name?” she begins. I have this weird feeling that the two are enacting a dialogue, and wonder how come Barrett as Love Bear knows most of the names of the audience and Pink Lady does not? Slight inconsistencies aside, the interaction is suitably awkward evoking patterns of intimacy and embarrassment that often go hand in hand.

Interactions are repeated as variations on the theme and the audience are drawn into differing levels of participation. At times clichéd questions are turned towards audience members. What would your friends describe you as? What is your idea of an ideal date? What is your profession? Age? What are you looking for in a partner? Unsurprisingly, these superficial questions yield little revelation about the person answering them, just as the constant use of this device in Brown Council’s dialogue limits us to a two-dimensional view of the characters. The entire audience, at times, becomes a blanket potential lover or life partner subjected to gushings of the characters’ wants and desires. At other times we play silent witness to things we may prefer not be involved in, but are now implicated in by our presence. We watch on as the Pink Lady (Blackmore) enacts an auto-erotic-asphyxiation fantasy submerging her head in a bucket of water as the pop classic “Take My Breath Away” provides the soundtrack. The vignettes all end the same way. The bells and time is up. A stopwatch-wielding Love Bear ushers the players off the stage.

In Melbourne, Six Minute Soul Mate came together as a playful response to the Next Wave theme “closer together” while embodying many of the provocations and contradictions of the theme. The performance played out as it moved through three small rooms above the Carlton Hotel. Each had its own sink and the whole scene was seedily reminiscent of a brothel—appropriate, given the love-for-sale ethos under examination. The work could have been described as ‘site-specific’, especially viewed in light of the Next Wave curatorial focus on non-conventional spaces. But in Sydney the siting of the piece in a gallery emerged as slightly problematic as the work failed to really inhabit the space. An awareness of large sections of the gallery not in use at any given time detracted from the type of forced closeness that had been achieved in Melbourne. The movement to three different locations around the gallery now seemed quite an arbitrary device for the change of scenery, and I was left wondering if this could have been achieved in a way more appropriate to the venue.

These are minor gripes though. The essence of the show I loved in Melbourne was undeniably still there. It lulls you along with gentle parody, and when it arrives at its poignantly striking images it does so with abrupt revelations amidst pity and laughter. The descent into grotesque seems complete in the last six minutes as I.T. funny-guy Allen (Barrett) lies trance-like on the ground rubbing his crotch and breathing “rub it rub it rub it” into the microphone. He is beyond expecting any of the “ladies” in the audience to oblige. I am disgusted and in stitches.

Brown Council, Six Minute Soul Mate, artists Fran Barrett, Kate Blackmore, Kelly Doley, Diana Smith, Imperial Panda Festival, Cleveland St, Surry Hills, Feb 14-16; Carlton Hotel, Melbourne, May 16-23, Next Wave 2008; http://browncouncil.blogspot.com

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 41

© Megan Garrett-Jones; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ahilan Ratnamohan, The Football Diaries

photo James Brown

Ahilan Ratnamohan, The Football Diaries

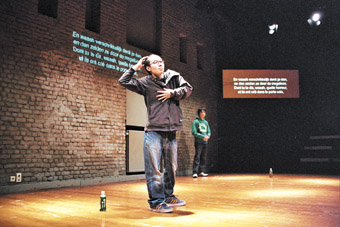

THE YEAR 1974 IS CENTRAL TO THE FOOTBALL DIARIES. IT IS THE YEAR THAT PROTAGONIST AHILAN RATNAMOHAN’S PARENTS MIGRATED FROM SRI LANKA TO AUSTRALIA TO STUDY AND THE YEAR THAT THE DUTCH BROUGHT TOTAL FOOTBALL TO THE WORLD CUP. THE FOOTBALL DIARIES BRAIDS THESE TWIN HISTORIES—OF FAMILY AND FOOTBALL—TOGETHER TO CREATE A SHOW THAT IS DECEPTIVELY SIMPLE AND SURPRISINGLY MOVING.

Born in Australia to Tamil parents in the 1980s, by the age of 18 Ratnamohan was playing professional football in Europe. The journey to this point is long, winding, and occasionally treacherous. In one of the first scenes, he is running in a forest, exhausted and on the edge of an endorphin-induced delirium: we are in Germany, where Ratnamohan has been toiling with a second-tier club. We flash back a few months to Malmö, Sweden, where he was trialling with the professional football team there. Then back a few years to Sydney, where schoolyard soccer is “black versus whites, ethnics versus skips. If you’re a halfy, stay in the middle, we’ll sort you out later.” Finally, we flash back a few decades so that Ratnamohan can introduce us to his heroes, the two Johans—Cruyff and Neeskens—of Total Football fame.

This time-travelling is accompanied by much philosophising. If you have ever heard an elite athlete speak about their sport you will know they approach zen-like states during play and can deliver zen-like aphorisms afterwards. (Think for instance of Zinedine Zidane’s claim that “When you are immersed in the game, you don’t really hear the crowd. You can almost decide for yourself what you want to hear. I can hear someone whisper in the ear of the person next to them”, or of Wayne Gretzky “I do not skate to where the puck is, but to where it will be.”)Ratnamohan is no different, intoning “I do not make mistakes; before making a mistake, I do not make it.” In this error-free world, football approaches utopia: there is no such thing as skin colour and the ball does not care who strikes it. The fully functioning team resembles a fully functioning community where someone willingly stands out on the lonely wing, sacrificing themselves for the greater good.

For all its utopian potential, however, football often falls far short. Indeed, the game is rife with racism and we see footage of Paolo Di Camio’s infamous straight-armed salute as well as Samuel Eto’o stopping the game and threatening to leave the pitch as he begs the crowd—No más—to stop their monkey chants. It is clear that soccer is starting to sour for Ratnamohan and it is not long before he pushes an injury too far and has to sit on the sidelines for three months before eventually coming home to Sydney and, luckily for us, the stage.

This particular stage is a small studio space with three walls: the back wall serving as a screen for projections and the side two as sparring partners for training sessions with the ball. Sometimes these sessions are a battle, other times they are ballet. Director and devisor Lee Wilson draws a vast physical vocabulary from Ratnamohan, who can tease, tussle and tango with the ball and then, just as easily, turn a delicate pirouette on it or partner a tender pas de deux. Every once in a while it feels as if this might become a pas de trois or trente, as the ball sails towards the audience, only to stop just short. This sense of restraint is also evident in the sections where Ratnamohan addresses the audience directly—the stories are elliptical, evocative and often self-deprecating. Yet even as he charms us, he also challenges us, as when he coolly assesses spectators as potential footballers: “I’ve bet you’ve got fast twitch muscle fibres”, he says, or “I’m worried about his vision.”

In fact our vision is excellent thanks to Lara Thoms and Fred Rodriguez’s videos, which manage to evoke the blurred vision of a player in training, the kaleidoscopic vision of a player ‘in the zone’, and the retro vision of a player dancing with ghosts: his heroes; his parents; his school mates; his younger self; even his future, older self. This sense of spectrality is amplified by Mirabelle Wouters’ lighting, which has Ratnamohan dancing with his own pink, green, yellow and grey shadows. Similarly, when he says “I can hear football”, we can too, through James Brown’s soundscape which enables us to appreciate football as Ratnamohan might—as rhythm, refrain, pulse, pitch and climax. Or in the language of dance that recurs throughout the piece, as ballet, tango and tap.

The many mentions of dance recall another, and as the show comes to a conclusion, and Ratnamohan steadies himself, breathing, balancing the ball on his head, I think of the last line of Yeats’ poem Among Schoolchildren: “How can we know the dancer from the dance?” In the language of football, how can we know the player from the play? In the case of Cryuff, we can’t; he now has a turn named after him. Likewise, in the case of The Football Diaries and Ratnamohan, it’s impossible to separate the two. No one else could have created this work and no one else could have performed it with such grace, agility and humility.

The Football Diaries, performer, devisor Ahilan Ratnamohan, director, devisor Lee Wilson, sound artist James Brown, video Lara Thoms, Fred Rodriguez, set & lighting design Mirabelle Wouters, dramaturg Alicia Talbot; Urban Theatre Projects, Bankstown, Sydney, April 22-May 2

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 42

© Caroline Wake; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Heather Bolton, Paul Lum, Affection, Ranters

AS MORE OF AUSTRALIA’S LARGER PERFORMING ARTS VENUES TAKE ON MORE RESPONSIBILITY FOR COMMISSIONING, CO-PRODUCING AND TOURING WORKS BY SMALL TO MEDIUM THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE COMPANIES, AND AS SCHEMES LIKE MOBILE STATES AND MAPS FACILITATE CREATION AND MOVEMENT OF WORKS, THE FULL TILT PROGRAM AT MELBOURNE’S ARTS CENTRE IS LIKEWISE BOLDLY PRESENTING A TRIO OF PRODUCTIONS FROM THE SECTOR’S LOCAL THEATRE INNOVATORS.

Full Tilt’s artistic director, Vanessa Pigrum, explains that her program has been focused, from inception, on cross artform works, but the opportunity arose to program three works with “a clear focus on text” and “musicality…there’s something orchestral about them.” Like an increasing number of plays, the programmed works also bear the influence of cross artform practices. Ranters’ new work, Affection, will doubtless display the sense of installation, music theatre and autobiography in the weave of their previous work, the popular and well-travelled Holiday. Pigrum also admits to pragmatism—three Arts Centre spaces just happened to be available at the right time, as were the artists she’d been in conversations with for up to two years: “it often takes at least 18 months to arrive at a production.”

The program includes a remount of Red Stitch’s Red Sky Morning (June 3-13); followed by a new play about love, “love as adrenalin, love as joy and hope, love as hysteria, love as a curse, love as weakness and love as redemption”, Poet #7, by Ben Ellis and directed by Daniel Schlusser (June 8-21); and the new work by Ranters, Affection (July 1–12), which has been in creative development with Full Tilt. Like its bracing predecessor, Holiday, Affection will be conversational, question the audience-performer relationship and work from the lives of its creators. Richard Watts will host “a newish initiative”, The Talk Show on 2 June, July 7, August 4 and September 1 at Black Box for those wishing to deepen their responses to the program and argue current arts issues.

Pigrum sees the trio of shows as “perfect winter fare: a warm coat, a glass of red and a discussion of meaty works”, and she’s hoping that audiences will take in at least two of the shows, to pick up on the resonances and continuities in these new contemporary theatre works.

I ask Vanessa Pigrum about her involvement in Full Tilt’s Creative Development program, which supports the emergence of new works. She describes her role as part-producer, part-dramaturg, involved early in the process “teasing out some of the key imperatives with the artists”, stepping back during the workshopping, offering frank feedback of the outcome” and sometimes suggesting the participation of another artist, “to add another dimension to the work.”

Pigrum tells me that Another Full Tilt program cluster will manifest in November-December with five productions including cross artform productions alongside innovative theatre works: Hayloft’s first production of an Australian play, about Jesus no less, and Kylie Trounson’s roller-skating fantasia set in the 1980s, The Man with the September Face, developed with Playwriting Australia. Full Tilt continues to do its substantial bit in the growth of opportunities for new work.

Full Tilt, Arts Centre, Melbourne, www.theartscentre.com.au/full-tilt/about.aspx