Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

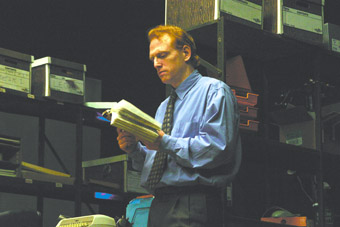

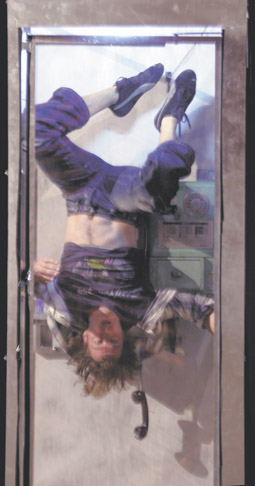

Scott Shepherd, GATZ, Elevator Repair Service

photo Chris Beirens

Scott Shepherd, GATZ, Elevator Repair Service

FROM NOW UNTIL JUNE THERE’S A WEALTH OF ADVENTUROUS ART TO EXPERIENCE ACROSS THE COUNTRY. HERE’S ADVANCE NOTICE OF SOME OF THE SHOWS THAT HAVE GRABBED THE INTEREST OF REALTIME’S EDITORS.

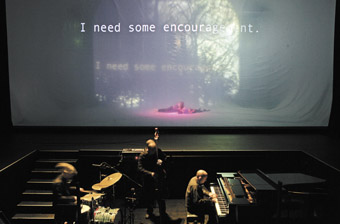

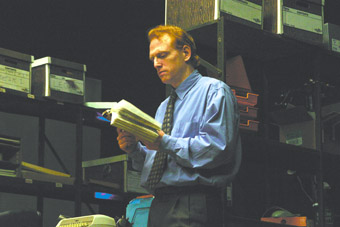

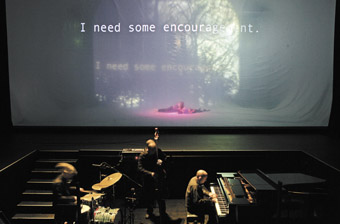

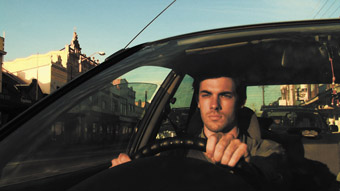

elevator repair service, gatz

You enjoyed the plethora of theatrical epics in this year’s Sydney Festival and you’re a fan of Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Or you’ve never read it but would love to have it read aloud to you, word for word. Then GATZ is for you: a seven-hour show that’s travelled the world since 2006 from New York’s Elevator Repair Service innovatively tackling the very nature of reading and performance. Adventures, Sydney Opera House, May 15-31; www.sydneyoperahouse.com

My Darling Patricia, Night Garden

photo Jeff Busby

My Darling Patricia, Night Garden

peformance space: my darling patricia’s night garden

Following the success of the award-winning Politely Savage, the long awaited Night Garden from My Darling Patricia looms (see photo page 2). This work furthers the company’s exploration of gothic Australia, distinctively fusing performance, puppetry, video and installation—here the skeleton of a burned-out house. The Australia-Japan photomedia collaboration, Trace Elements, is also on show until March 21. And in May, There Goes the Neighborhood, curated by Zanny Begg and Keg de Souza, explores the politics of urban space. Meanwhile performer Rosie Dennis’ highly anticipated new show Fraudulent Behavior premieres in June. Performance Space, Night Garden, CarriageWorks, March 6-14; www.performancespace.com.au

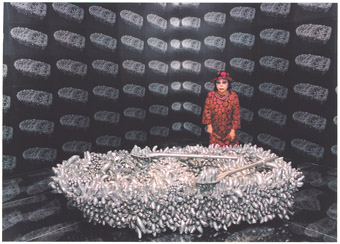

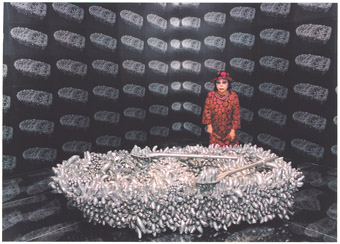

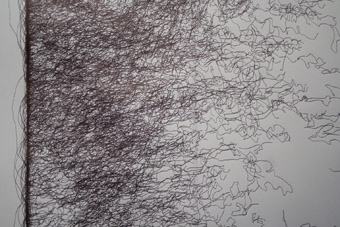

Yayoi Kusama, Walking on the Sea of Death, 1981

courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro Gallery, London and Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo

Yayoi Kusama, Walking on the Sea of Death, 1981

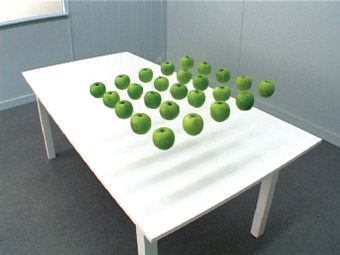

mca: yayoi kusama: mirrored years

You won’t see stars, but spots will certainly appear before your eyes when you enter the immersive worlds of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama (see page 3). Single works have been exhibited previously in Australia but here is an exhibition on the grand scale: film, performance documentation, sculpture, installation work and painting, including 50 recent print works. A unique vision, a transformative experience. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Feb 24-June 7; www.mca.com.au

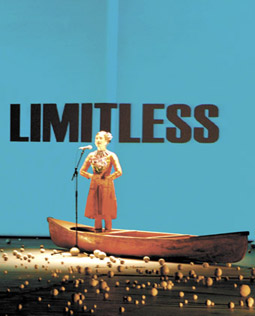

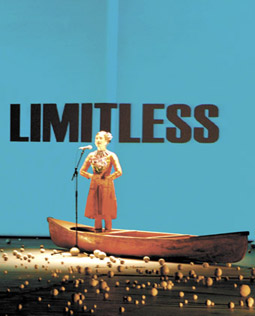

malthouse/arena: goodbye vaudeville charlie mudd

Some of the most innovative theatre of recent years (The Black Swan of Trespass, The Eisteddfod) has come from Melbourne’s Stuck Pigs Squealing underpinned by the collaboration of director Chris Kohn and writer Lally Katz. Kohn is now artistic director of Arena Theatre, but the creative relationship with Katz persists in a Malthouse-Arena co-production, Goodbye Vaudeville Charlie Mudd. With Kohn’s keen eye for the languages of theatre this show resurrects the vaudeville world of 1913 Melbourne but through the prism of Katz’s surreal imaginings. Malthouse, March 6-28, www.malthousetheatre.com.au; www.goodbyevaudeville.blogspot.com

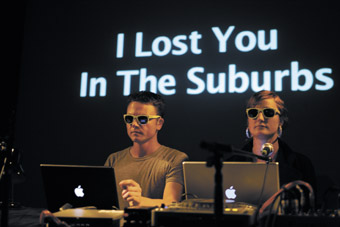

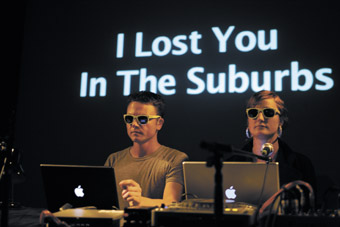

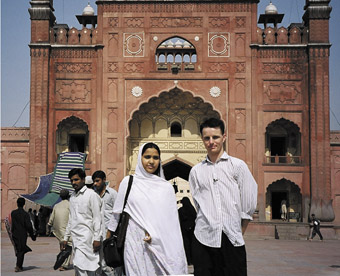

clocked out: the wide alley

The dynamic Brisbane-based duo of composer-pianist Erik Griswold and percussionist Vanessa Tomlinson have an extensive 2009 program taking them to Sydney, Auckland, remote Queensland and Canberra. In March at Sydney Opera House’s The Studio and then at the Auckland Festival they will fuse traditional music from the street and opera of China’s Sichuan Province with their own avant-garde creations. Aural excitement is guaranteed in a Clocked Out gig. The Studio, Sydney Opera House, March 1, 5pm, www.sydneyoperahouse.com

stc: martin crimp’s country

Looking well ahead to late June, here’s one for the diary: Benedict Andrews’ production of The City by leading English playwright Martin Crimp (Attempts On Her Life, The Country). Those who saw Andrews’ engrossing production of Marius von Mayenburg’s Eldorado for Malthouse in 2006, will recognise what has doubtless attracted the director: everyday suburban life goes doggedly if bizarrely on while a ‘secret war’ rages. In the meantime STC’s offering a welcome revival of Tom Stoppard’s Travesties in March and two visiting Kafka shows in April: Kafka’s Monkey (from his Report to the Academy) performed by the UK’s Kathryn Hunter, and an Icelandic physical theatre rendition of Metamorphosis (p3, p16). STC, The City, June 29-Aug 9, www.sydneytheatre.com.au

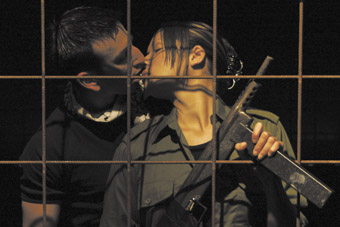

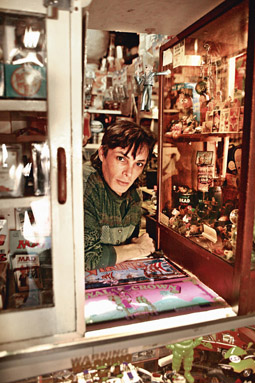

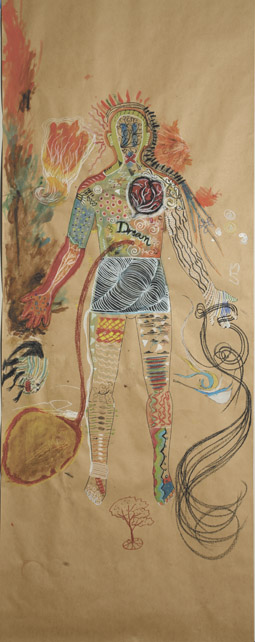

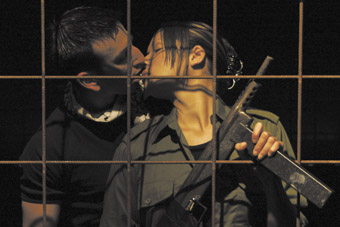

casula powerhouse: nam bang!

Thirty four years after the Vietnam War, Casula Powerhouse is mounting a major show of works by 25 artists from Australia, Vietnam and beyond that reflect imaginatively on the experiences of those involved and their descendants. Artistic director Nicholas Tsoutas aptly asks, “When does war become art?” An international conference, with prominent arts writer and activist Lucy Lippard as keynote speaker, will take place April 17-18. Casula Powerhouse, Sydney, April 4 –June 21; www.casulapowerhouse.com

sound travellers 2009 and free cd

Now in its second year, Sound Travellers has a substantial touring program of sound art, improvised jazz and contemporary classical music.You can see the program on the organisation’s website and while there request a free CD of a collection of works by the touring artists—including Topology, Ross Bolleter (a featured artist in Ten Days on the Island), Pivot, Joel Stern, Ensemble Offspring, Mark Isaacs, Camilla Hannan, Klumpes Ahmad and more. www.soundtravellers.com.au

double take: ann landa award 2009

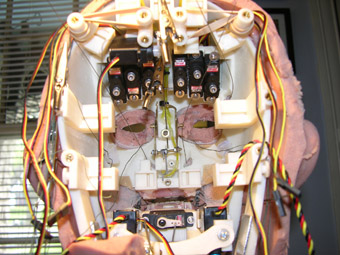

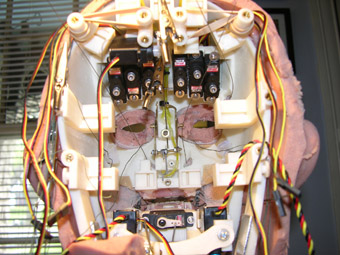

You may well do a double take when you see the list of artists competing for the 2009 Ann Landa Award for Video & New Media Arts: Cao Fei (People’s Republic of China), Gabriella Mangano & Silvana Mangano (Australia), Phil Collins (UK), TV Moore (Australia), Lisa Reihana (New Zealand) and Mari Velonaki (Australia). Yes, the award’s gone international. The mix of video, interactive robotics and digital photography will inherently tackle the big question, “How can we be both the self, and an other at the same time; both a self, and an out-of-body split self?” Art Gallery of New South Wales, May 7-July 19, www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au

the chauvel cinema does expanded cinema

As part of its Cinematheque program, Sydney’s Chauvel is showing an expanded cinema program “devoted to (mostly) Australian experimental art films that use multiple projectors.” The program includes Paul Sharit’s twin screen, looping Razor Blades (US,1968), John Dunkley’s pattern-play Rotunda, Dirk de Bruyn Experiments (1982), a veritable catalogue of techniques and “a scream from suburbia”; Arthur and Corinne Cantrill’s The City (1970), “a composite view of the city is created by three films screened simultaneously”; and from the same filmmakers, Meteor Crater—Gosse Bluff (1978). Also coming up at the Chauvel on March 6 is a rare opportunity to see two recent films by popular, award-winning Czech filmmaker David Ondricek. Chauvel Cinema, Paddington, Sydney, Feb 23, 6.30pm; www.chauvelcinema.net.au

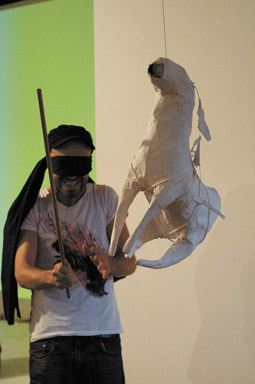

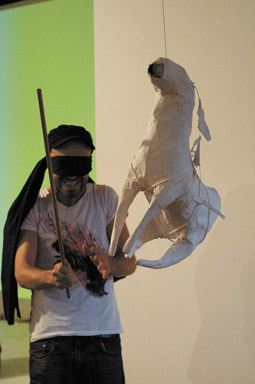

blacktown arts centre: blind as you see it

We haven’t seen their work yet, but the emerging Shh Company are tackling a challenging subject with their director and composer Michal Imielski. Blind As You See It fuses puppetry, theatre, music and dance in an exploration of the experience of losing one’s sight. Blacktown Arts Centre, Sydney, Feb 27-28; www.artscentre.blacktown.nsw.gov.au

syncretism: lawrence english + no anchor

Brisbane’s No Anchor experimental duo “creates an utterly engulfing wall of sound” while Lawrence English generates immersive sound fields with material from his album, Colour for Autumn. With a guest appearance from Heinz Riegler. Judith Wright Centre, March 21; www.judithwrightcentre.com

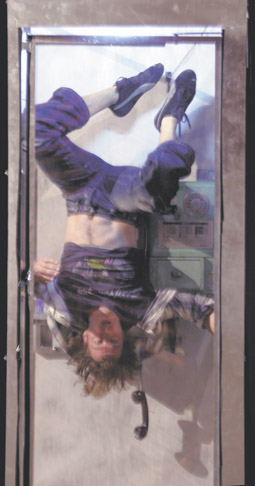

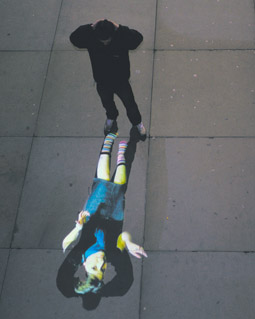

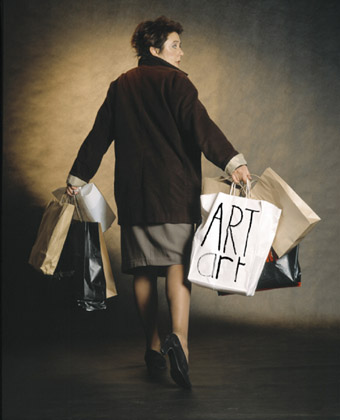

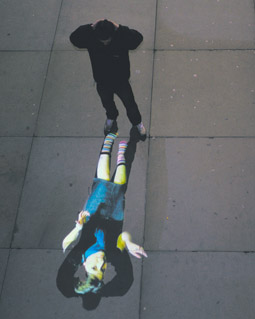

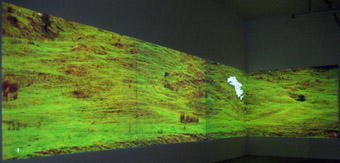

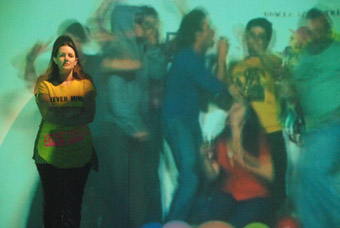

Fleur Elise Noble’s filmic-theatre production 2-Dimensional Life of Her

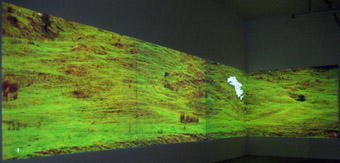

come out: 2-dimensional life of her

One of the many intriguing hybrid performances in the 2009 Come Out Festival is young Adelaide artist Fleur Elise Noble’s 2-Dimensional Life of Her (see photograph on page 2). An earlier version won the Best in Show award in the 2008 Brisbane Festival’s Under the Radar program. The work involves three projectors, animation, drawing and an audience immersed in paper, and will have an accompanying drawing installation at the Experimental Art Foundation. Come Out 2009, Adelaide, May 18-30; www.comeout.on.net

griffin theatre company: ross mueller’s concussion

In a co-production with STC, Griffin is staging Ross Mueller’s Concussion, an edgy comedy about a man who wakes up without a memory. Melbourne’s Mueller, like Tasmania’s Tom Holloway, is a distinctive and relatively new voice in Australian theatre. In the meantime, don’t miss Ranters’ Holiday at The Stables (it closes Feb 28)—a potent example of the strange paths opening up in contemporary theatre. Griffin Theatre Company, Concussion, Wharf 2, Sydney, March 17-April 4; www.griffintheatre.com.au

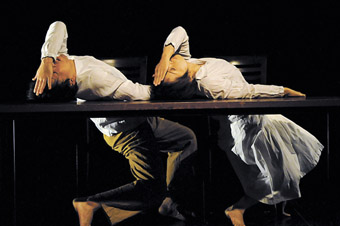

song company: tenebrae iii

An annual highlight has been the Song Company’s Good Friday event, a powerful fusion of song and dance, directed in the past by Kate Champion at Sydney Town Hall (2005, 2006), this time by Shaun Parker in the vast industrial spaces of CarriageWorks. Tenebrae III is based on Gesualdo’s Responsories for Holy Week, sublime music evoking the spiritual extremes of belief. And you don’t have to be Christian to appreciate the emotional power of Tenebrae III. CarriageWorks, Sydney, April 8, 10; www.carriageworks.com.au

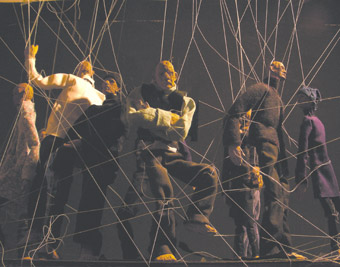

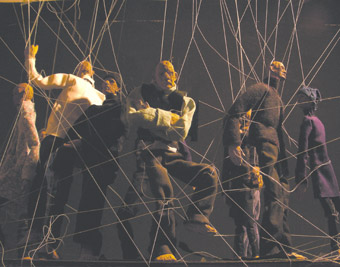

Metamorphosis, Vesturport Theatre

photo Eddi

Metamorphosis, Vesturport Theatre

10 days on the island

This unique across-the-island biennial event draws on its own and other island cultures to entertain and challenge us. It’s a wonderfully intimate live-in festival. In 2009 the festival includes a significant Indigenous dance program in Launceston and innovative performances all over, including two hot shows from Iceland. See page 16 for Carl Nilsson-Polias’ interview with Ten Days director Elizabeth Walsh. Ten Days on the Island, Tasmania, March 27-April 5; www.tendaysontheisland.org

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 10

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

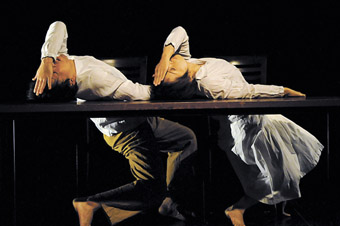

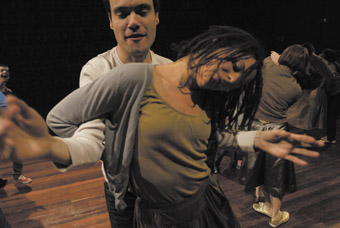

Byron Perry, Antony Hamilton, Lee Serle, Stephanie Lake, I Like This, Chunky Move

photo Genevieve Bailey

Byron Perry, Antony Hamilton, Lee Serle, Stephanie Lake, I Like This, Chunky Move

THE VARIOUS LABELS WE USE TO CATEGORISE THE CAREER DEVELOPMENT OF ARTISTS—EMERGING, PRO-AM, MID-CAREER, FRINGE, PROFESSIONAL—ALWAYS HANG UNEASILY UPON THEIR SHOULDERS, LIKE A RENTAL TUX THAT’S BEEN THROUGH THE WASH ONE TOO MANY TIMES. THEY’RE USUALLY EMPLOYED TO POSITION SOMEONE WITHIN A LARGER ‘INDUSTRY’, BUT THE AMORPHOUS NATURE OF THE ARTS, ALONG WITH FICKLE FUNDING, THE DIFFICULTY IN DEFINING A ‘MAINSTREAM’ AND THE WONDERFUL CROSS-DISCIPLINARY ACTIVITIES WHICH MAKE UP SO MUCH OF OUR CREATIVE LANDSCAPE CONTRADICT SUCH PIGEONHOLING. THREE PRODUCTIONS WHICH APPEARED AT THE TAIL-END OF 2008 ARE CASES IN POINT.

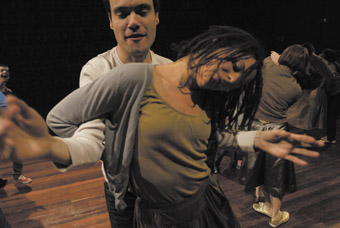

Byron Perry and Antony Hamilton are amongst the most recognisable contemporary dancers in Melbourne, having featured heavily in the calendars of Chunky Move and Lucy Guerin Inc for several years as well as popping up in the works of younger dancemakers. Their first original collaboration, I Like This, can’t really be classed as the debut of two emerging choreographers. There are two immediately apparent reasons: firstly, both dancers have distinct styles and interests which have been evident in their previous performances for others. Secondly, the influences of these earlier mentors have left particular traces in the witty, astute form of I Like This.

Billed as a choreographic conversation between Hamilton and Perry, the work is partly an exploration of the process of dance-making, in which their ideas of what the work is to become are played out around them by a cadre of talented performers. But while this kind of meta-theatre is hardly ground-breaking—and reached a superb apex in Guerin’s and Chunky Move’s respective contributions to the last Melbourne International Arts Festival (see RT88, p4), both starring Hamilton and Perry—I Like This takes its concepts in pleasing new directions. It’s not a navel-gazing piece of the sort presented in Wendy Houstoun’s Desert Island Dances, another MIAF event. Here, action supercedes analysis.

The duo clearly recorded their rehearsal process and used the result to produce a kind of remixed dance. The performers begin to move, then rewind, skip or become stuck in loops. All the while, Perry and Hamilton sit surrounded by lighting panels, power boards and snaking cables, orchestrating the handheld lamps carried by the dancers. In fact, Perry and Hamilton’s visual design for the work deserves particular mention, becoming a character almost in itself, with hundreds of perfectly executed changes whose sometimes stroboscopic effect makes lighting operation appear a form of choreography in its own right.

It’s self-reflexive dance, certainly, but by incorporating technology in such a sophisticated way it becomes something much more. And when the work ends with the two choreographers covered by a giant quilted doona, lights sparking underneath like flashes on a distant mountain range, the result approaches the sublime. Emerging artists? Far from it.

Avast, Black Lung

photo Jeff Busby

Avast, Black Lung

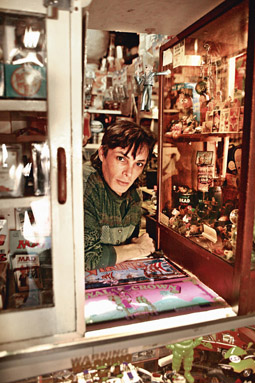

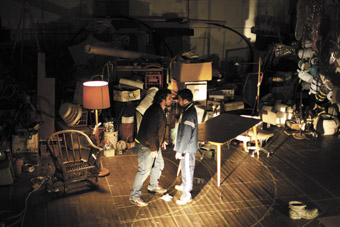

The Black Lung are another ensemble well entrenched in Melbourne’s independent arts scene while occupying an utterly, defiantly outsider space. But, testament to the inadequacy of such categories, they were picked up by the Malthouse for a residency in its Tower program.

The Tower season consisted of a remounting of Avast, first produced three years ago, and a new work entitled Avast II: The Welshman Cometh. The theatre itself was radically transformed during the three month residency, outfitted with dingy couches, graffiti-covered walls and a massive wooden set filled with animal skulls, worn leather, animated dummies and dusty ephemera. Both productions were equally ramshackle, eclectic and brilliantly detailed.

The Black Lung create the kind of anarchy that can only result from incredible precision, an effect most notably associated with Forced Entertainment. During Avast, a confrontation between two brothers haunted by a legacy of familial murder and betrayal is interrupted by a falling spotlight which crashes to the ground inches from the actors’ feet. They are visibly shaken as they attempt to continue the scene, and convincing the audience that this wasn’t a pre-planned moment only proves the astounding capabilities of these performers. Similarly, the constant sense of competition, potential violence and despair of the actors themselves creates a brilliant blurring of understanding—are we watching something taking place, or something failing to take place?

Underneath the deliberate chaos is a thick questioning of theatre, narrative convention and masculinity. The two works are almost entirely composed of pastiche, quotations from film, literature and generic devices overlapping constantly. It’s all brutally blokeish too, with the only female character killed in the opening moments of Avast (unless you count another male character’s inexplicable change in gender halfway through the second work). And while Avast II is evidently a new work, the three years of development accorded Avast have made it one of the tightest, funniest, scariest pieces of theatre I’ve seen in years.

Collapse, Red Cabbage Collective

photo Matthew Scott–Cheeky Monkey Enterprises

Collapse, Red Cabbage Collective

Melbourne collective Red Cabbage might be the artistic equivalent of the Slow Food movement—like incidental fellow travellers such as Eleventh Hour Theatre, Red Cabbage eschew quantity for quality, creating one work per year. The time commitment was certainly evident in Collapse, an epic, large scale installation and performance located across a remote former maritime precinct in Williamstown. Audiences were transported by a 20-minute boat ride to a post-apocalyptic world both staggering and serene. Disembarking from the vessel, we were met by linen-clad survivors of some disaster dredging canned food from the ocean, hauling rotten row-boats across concrete as the twilight descended; we gathered in a vast, weed-strewn warehouse where women lyrically spoke around the mysterious disaster which had befallen the community; we roamed a maze of sheds, alleyways and ruined sites housing countless traumatised inhabitants coping with the new reality into which they’d been reborn. An alchemist conducted strange experiments in a bubbling lab while a babbling wreck spewed poetry in a nearby shanty. The enigmatic, voyeuristic voyage ended in a gargantuan warehouse-cum-cinema, a ragged corps of drive-in speakers standing to attention before the flickering celluloid images retrieved from a lost world. Gaps in the canvas screen revealed blue skies and drifting clouds, as much a memory as the filmic footage being projected. The survivors gathered before this iconic scene in reverential silence. Minutes later, it was all over.

Collapse’s narrative was piecemeal and its meaning kept obscure, allowing each visitor their own interpretation. The audience was allowed to wander individually; unlike the masterfully subtle control of attention exercised by another interesting company, Peepshow Inc’s similar The Mysteries of the Convent (2008), there were plenty of opportunities to miss a dramatic moment or provocative scene here. Collapse’s effect was a cumulative one, however—even the relatively uneventful prefacing boat ride worked to establish a mood of quiet distance and reflection, producing a sense of reverie.

It’s difficult to stamp any of these three works as “emerging”, though all fit a technical definition. But all are equally the products of artists who have been honing their crafts for years and all exceed journeyman status. The next evolutionary step for each will most likely prove just as hard to classify.

I Like This, choreography, direction, lighting, sound Antony Hamilton, Byron Perry, performers Hamilton, Perry, Stephanie Lake, Alisdair Macindoe, Lee Serle, costumes Paula Levis, Chunky Move Studios, Nov 20-29; Avast and Avast II: The Black Lung Theatre Company, The Welshman Cometh, performers Sacha Bryning, Gareth Davies, Thomas Henning, Mark Winter, Thomas Wright, Dylan Young, sound design, music Liam Barton, lighting design Govin Ruben,Tower Theatre, CUB Malthouse, Nov 12 – Dec 6; Red Cabbage, Collapse, creators Louise Morris, Tania Smith, Kirsten Prins, Anna Hamilton, performers Jason Lehane, Claire Reynolds, Maria Sirpis, Jason Cavanagh, Kate Boston Smith, Alice Claringbold, Ross Farrell, Krista Green, Portia Chiminello, Carlo Marasea; Seaworks, Williamstown, Melbourne, Nov 19-30, 2008

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 12

Grayson Millwood, Roadkill, Splintergroup

photo Tim Bates

Grayson Millwood, Roadkill, Splintergroup

REALTIME’S COVERAGE OF LAST YEAR’S MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL FEATURED AN EXCITING RANGE OF NEW DANCE WORK FROM LOCAL ARTISTS. FOR THE DEPLETED SECTOR IN SYDNEY, MASS MIGRATION WAS SERIOUSLY CONTEMPLATED. IN MARCH, IN A WELCOME JOINT INITIATIVE, THE THREE HOUSES OF MELBOURNE’S CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE CULTURE—ARTS HOUSE, DANCEHOUSE AND MALTHOUSE ARE THROWING OPEN THEIR DOORS TO CO-HOST TWO WEEKS OF CONTEMPORARY DANCE PROGRAMMING IN THE FORM OF DANCE MASSIVE. THE GENEROSITY IMPLIED IN THE EVENT’S TITLE IS REFLECTED IN A PROGRAM OF 15 WORKS FROM WITHIN AND OUTSIDE THE HOME STATE.

Part of the function of such events is for audiences to survey the form, to muse on its preoccupations. What strikes me in promotional literature for the programmed works is the language constellating around oppositions, the difference between states of being and, biting at those binary ankles, ideas of liminality and hybridity. These spaces of uncertainty and possibility occur both in the form and subject matter of the works. Live performance meets film and installation in Russell Dumas’ Huit à Huit. In Lucy Guerin’s Untrained, four men—two dance trained, two not—“show what each of those bodies can do with the same set of instructions, what they have in common and where their physical histories set them apart.” In 180 seconds in (Disco) Heaven or Hell, “speed dating meets pomo disco” and comes with The Fondue Set’s customary warning of “possible bad dance moves.”

Oppositional themes abound: circadian rhythms underscored by driving beats; population growth and the auditory phenomenon of feedback” (Rogue’s A Volume Problem and The Counting); Australians homesick in Berlin (Splintergroup’s Lawn); a couple stranded in the middle of nowhere (Splintergroup’s Roadkill); the monster within (Jo Lloyd’s Melbourne Spawned a Monster); two performers/two viewers (Inert); the substitution of real life for imitation (Luke George’s Lifesize). Shelley Lasica’s Vianne tests the fissures; in Limina, Michaela Pegum dances at the point where one thing becomes another and is for a time both; Helen Herbertson’s Morphia Series takes us directly to dreamstate (do not pass go); The Fondue’s No Success Like Failure playfully lays bare the schizophrenic state of the dancing life and Chunky’s Mortal Engine dares to come between the performer and her light source.

Steven Richardson, Artistic Director at Arts House, sees Dance Massive as “creating some essential critical dialogue around contemporary dance, setting a national context to present work in a concentrated cluster of programming” and also as offering the chance to host some international guests, “either presenters or potential co-producers, to really enter into that dialogue (and possible co-production) with Australian artists, many of whom are at the leading edge of contemporary dance internationally.” Currently in Australia, according to the Dance Massive program, there are around 50 dance companies and more than 200 choreographers investigating a range of techniques, culturally diverse forms, contexts and media. “Australian contemporary dance is in demand internationally. It has a strong track record for touring work,” says Richardson.

Byron Perry, Anthony Hamilton, Simon Obarzanek, Ross Coulter, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc

photo Untrained Artists

Byron Perry, Anthony Hamilton, Simon Obarzanek, Ross Coulter, Untrained, Lucy Guerin Inc

Dance Massive also represents for the partners “a broad audience development strategy, the possibility to create a strong concentration of work over a specific time period…We don’t have the resources to mount a festival but a concentrated program has some added benefits over and above an annual program.”

“Having companies like Chunky Move co-operatively program at the same time as some of the more emerging companies”, says Richardson, gives younger companies and independent artists a chance to have their work seen in the broader context. “I think there’ll be some interest and benefit around the positioning of different kinds of work over the same time period.”

Visiting guests will have an opportunity to see complete works rather than excerpts. “The Australian Performing Arts Market does a terrific job in terms of a kind of broad brushstroke picture of the Australian cultural landscape. But I think having a genre-specific showcase, for want of a better term, creates all sorts of other possibilities. And the fact that we’re able to invite presenters or potential co-producers who have a very strong interest in dance, who can see 12-15 works over a six-day period—that’s a fairly attractive proposition for someone who’s engaged in looking at Australian work.” It’s also a less competitive environment for artists. “Presenting a full-length work with full production values is really important. It honours the work, honours all the effort that’s gone into making it.”

As well as the dance program, there’s an industry forum day on the Monday where artists who may not be in the program will talk about their work. “Australian dance is in a position now where artists have a greater degree of self-esteem and can just talk about upcoming work.”

“Since the demise of Greenmill”, Richardson observes, “there hasn’t really been a dedicated event focusing on contemporary dance. There have been a number of ancillary programs associated with arts festivals. But I think having a stand-alone contemporary dance project is timely and Melbourne is the place to host it. There’s already a critical mass and an ecology of dance in Melbourne that can support this practice. We have a very nice temporal moment, a good confluence of presenters in Melbourne who are open to this idea, so it’s time to give it a go.”

And if it all goes well, Dance Massive may well become a biennial event. Says Richardson, “We’ll certainly undertake some evaluation once we get through the first one and see if we’ve got the design close to right and make some adjustments after that. It may be we’re trying to do too much, or too little. And there are some gaps in the program. Contemporary Indigenous work is something we haven’t really been able to support this time. That’s the tyranny of distance, of resources, of funding. There’s some intercultural, cross-cultural work that, for various reasons, both to do with funding and resources but also to do with the availability of particular works, we haven’t really been able to present. But they’re definitely on the agenda. In fact, if I had to say where the gaps are I’d have to highlight those two areas of potential strength in Australian dance that we haven’t been able to support this time round. We hope to run three Dance Massive episodes as a pilot and see how we go after that.”

Dance Massive, March 3-15; www.dancemassive.com.au

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 14

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

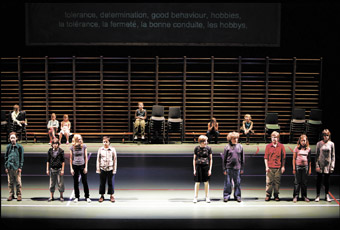

play:ground

photo Irene Rincon

play:ground

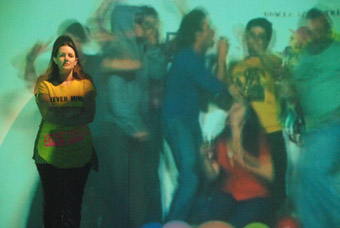

IN 2008 I SAW A LOT. ONE HUNDRED AND NINETY EIGHT LIVE PERFORMANCES BY MY RECKONING, NOT INCLUDING LIVE MUSIC. AND I SAW A LOT OF KIDS ALONG THE WAY. I SAW KIDS SHOT OR GARROTTED, DRENCHED IN BLOOD (THE WOMEN OF TROY; THANKS BARRIE KOSKY) OR SCREAMING THEIR INJUSTICES AT ME. I ALSO SAW KIDS BARING RICTUS-LIKE SMILES AS THEY BEGAN PAINFUL BALLET CAREERS, AND KIDS WITH NO DREAMS OF STARDOM RELUCTANTLY DRAGGED ONSTAGE DURING FAMILY SHOWS. I SAW ADULTS ACTING AS CHILDREN, BUT THAT’S RARELY INTERESTING.

Maybe I’m presuming, but I’m pretty sure we were all kids once. I don’t have any children but I think childhood is a fine subject for any artistic worker. This opinion piece—and that’s all it is—is not really a comment on the Bill Henson debate, though it will necessarily intersect with the murky issues that case brought to public attention. What interests me here is less about the depiction of children in art and more about their participation.

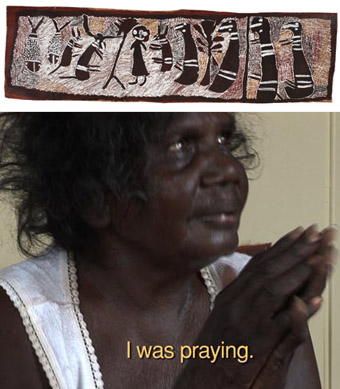

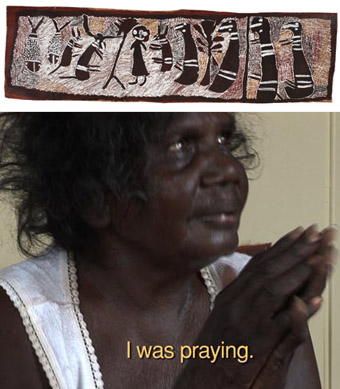

Last year I attended a performance directed by a VCA masters student entitled play:ground. Claudia Escobar created the work as a response to the child soldiers who exist around the world, including in her homeland of Colombia. The piece was performed in a twilight-bound park by primary school children who engaged in mock battles, were terrorised or recruited by sinister authority figures, and turned upon each other in savage fashion as they became inured to the reality of violence.

For these child performers, as for real child soldiers, killing bore no more reality than a videogame or schoolyard playfight. This was the point of play:ground, in part. But the spectacle of pre-adolescent kids riddling each other with machinegun bullets or emerging from the trees covered in the sackcloth hoods of terrorists and toting fake semi-automatic weapons was authentically disturbing for its adult audience. An effective and deeply provocative evocation of a very real contemporary horror, yes, but also more unsettling in its involvement of real children playing out—and thus vicariously participating in—the problem.

Barrie Kosky’s Women of Troy was an equally violent spectacle. Its unending cacophony of ear-splitting gunshots was either traumatic or numbing, depending on your response. And near the work’s climax, as dictated by Euripides himself, the figure of a dead young boy appears, carried in a bloody cardboard box. As with play:ground, I doubt that the child in question was adversely affected by the performance. I played dead when I was a kid.

But I’m surprised that the spectacle of violence towards children doesn’t raise hackles in the way that sexuality does. I’m sure it’s something to do with our troubled notion of consent. Children are assumed (legally at least) to be unable to make informed, adult decisions regarding certain aspects of their lives, and laws and safeguards are in place to make those decisions for them. I have no problem with this. But the Henson affair barely touched upon a more challenging aspect of this system of protection: is a child’s right to self-determination also taken out of their hands in the realm of representation? That is, can an adult decide whether and how a child’s image may be presented in the public sphere?

An Anne Geddes calendar featuring babies in pot-plants or dressed as watermelons is a commercial goldmine, but how would the same buying public feel about similar shots featuring people suffering dementia or Alzheimer’s? Not so cute, sure. But ethically on the same level. Former UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar has suggested that “a society is judged…by the quality of life which it is able to assure for its weakest members.” I wonder if that concept can be extended to the rights we accord others to control their self-representation.

For several years I tutored tertiary students in a subject on art and censorship. Every new class arrived with a surprisingly regular set of opinions on the topic— censorship was unequivocally wrong, and freedom of speech was an essential component of our culture. Western liberal democracy is founded on this rhetoric, though a little nudging suggests limits most people would agree with. Censorship might not be so bad when it comes to child pornography, religious vilification or racial discrimination, for instance. And indeed, if we broaden our notion of censorship from the simple state-imposed variety to the more organic forms of censorship—the way we censor our own thoughts and comments, or the community censorship that exerts an influence on the discursive relations amongst any social group—the black ban on capital-C censorship becomes more muddled.

And what irked me most about the Henson debate and its offshoots was that a most pernicious form of censorship was exercised by even the artist’s most strident defenders. What was absent from discussions was the voices of those in question, for whom we’re all happy to speak. Children simply do not have a public voice in the way that a mature white male artist or a newspaper columnist or a prominent politician has. The censorship of a child’s voice is not legally enshrined but it’s no less institutionalised. And I suppose my concern here stems from the fact that despite all the kids I saw onstage last year, I’ve never had a sense that anyone is particularly interested in speaking to, rather than for, a demographic whose minority status stems from age alone.

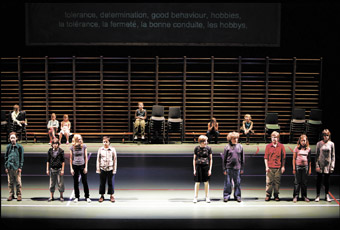

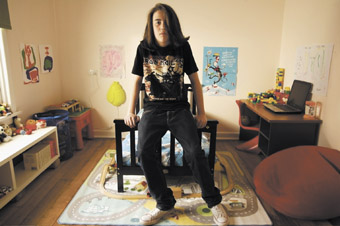

The one exception could have been Tim Etchells’ That Night Follows Day, which appeared at the Melbourne International Arts Festival. Here, a few dozen children of various ages chanted a litany of complaints to their audience: “You teach us that in the world there are bad men/ That monsters are not real/ That words are only words/ That the shadows are nothing to be frightened of.”

My sister has recently been working on a documentary called Eleven, which features interviews with 11-year-olds from around the world. Her theory is that kids at that age are no longer children but not yet adults. The results are compelling. Her subjects speak about sexuality, terrorism, cold fusion technology, romance, action movies and politics, often in the same sentence. They are thoughtful and generous, mostly startled that someone would care to hear their opinions on things that are normally considered the discursive province of grown-ups alone.

I recommended That Night Follows Day to my sister, who attended a showing followed by a public discussion of the piece. She was disappointed to learn, as I had, that the text itself had been written by adults. A producer explained that the thoughts of the juvenile participants wouldn’t have produced the effective, impactful political statement which the work ended up delivering. They would have talked about rainbows and boyfriends. I have to disagree.

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 15

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Siren, Ray Lee

photo Steven Hicks

Siren, Ray Lee

ITS UNIQUE BREADTH OF GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATIONS AND ITS DISTINCTIVE SENSE OF PAN-ISLAND FRATERNITY HAVE ALWAYS SET TEN DAYS ON THE ISLAND APART FROM ITS MAINLAND FESTIVAL COUSINS. FOLLOWING ON FROM HER WORK IN 2007, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ELIZABETH WALSH SEES THIS YEAR’S PROGRAM AS “GOING A BIT FURTHER” WITH REGARD TO PROVIDING AN EVEN MORE INNOVATIVE AND CHALLENGING PROGRAM OF EVENTS.

When I interviewed her, Walsh was in Melbourne for the opening of Woyzeck at the Malthouse Theatre. This particular translation and adaptation of the Georg Büchner play is by the Icelandic writer, director, actor and former gymnast Gisli Örn Gardarsson, whose version of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis is one of the headline productions at the Ten Days festival. The popularity of Gardarsson’s work on our shores, though seeming rather sudden, has been only a matter of time. With his theatre company, Vesturport (see page 3), Gardarsson has become a darling of the British theatre scene thanks to the extreme physical acrobatics he employs in his theatrical adaptations—the result of bringing his gymnastic skills and aesthetic to bear on projects from Romeo and Juliet to Faust. And, on most of these pieces, he has collaborated with Australian musicians Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, whose output in recent years has increasingly included scores for stage and screen. In terms of theatrical antecedents, Gardarsson’s Metamorphosis is a very different dish to that served up by Steven Berkoff in 1969. Where Berkoff used his physical alacrity and invention to construct Gregor Samsa’s entire world from lights and a few bits of scaffolding, Gardarsson’s vision is grander and locates Samsa within a much more traditional theatrical design. Nevertheless, both are very much vehicles for physical virtuosity and, in that respect, Gardarsson’s pedigree is hard to fault.

On the topic of pedigree, Wu Hsing-kuo’s company has the potentially hubristic moniker of Contemporary Legend Theatre. However, having studied Chinese opera from the age of 11 and performed as lead dancer for the extraordinary Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, Wu Hsing-kuo has earned the title. He brings to Tasmania what Walsh describes as his “party piece”—a solo performance of King Lear. Though Lear is not what everyone would call a party, there is something undeniably attractive about seeing such an outrageously ambitious project undertaken by such a capable performer. This kind of transcultural adaptation of Elizabethan drama into other equally strong theatrical traditions has some great forebears, such as Akira Kurosawa’s use of Noh elements in his acclaimed films Ran and Throne of Blood. In Wu Hsing-kuo’s version, the narrative arc of Lear’s fall from regal pageantry to barren essentialism is echoed in the costumed glory of traditional Chinese opera being gradually stripped away as the old king’s mind unravels before us.

On the musical front, Ten Days on the Island is flying Perth composer Ross Bolleter back and forth in search of Tasmania’s most attractively derelict pianos. John Cage made the ‘prepared piano’ popular and Bolleter does the same for ‘ruined pianos.’ In other words, he takes those weathered wrecks that have been sitting in a galvanised iron outhouse for a few too many decades and uses their unique aural fingerprint of decay to create his own particular brand of composition. For Walsh, this has been the perfect opportunity for the festival to interact both with the colonial heritage of Tasmania and smaller regional communities. For Bolleter, it is an opportunity to interrogate the idiosyncratic resonances of some truly decomposed ebony and ivory. And for the audience, it is a potentially inspiring call to arms and good reason to lift the sheets from those long-forgotten instruments. Having toured to Stanley, Derby and Ross, the pianos will eventually be installed in the equally neglected and remarkable Bond Store at the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery in Hobart, where their stories and their sounds will both be on show.

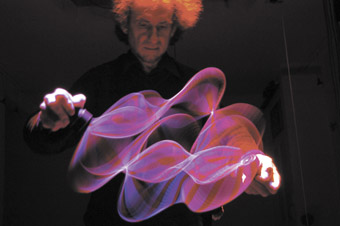

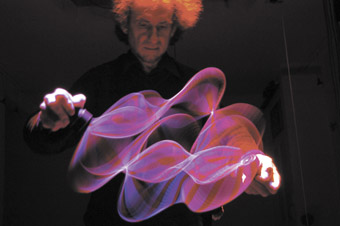

In a strangely beautiful parallel, another installation-cum-concert takes its aural inspiration from a far more modern instrument—the siren. Created by English sound artist Ray Lee, Siren stretches the possibilities of the Doppler effect to an enticing extreme. Presented at Launceston’s Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery, Walsh points out that the venue’s role as a nexus for science and art makes it the perfect place to install this musical experiment. Set on giant tripods, sirens and lights rotate on long arms to create a finely tuned field of sound that is interspersed with inevitable beats and natural harmonics. Within this space, the audience is encouraged to move around, adding another level of sonic mobility and distortion and thereby affording each listener an entirely personal experience of the sound. Together with fellow performer Harry Dawes, Lee moves around the space with the audience, operating the sirens and adjusting their tone. Lee is interested in what he describes, with a nod to outmoded physics, as the “circles of ether”—the invisible forces of electromagnetism and the like. In Siren, he creates an appreciable representation of these forces using the invisible yet sensible nature of sound to make manifest the waves and concentric spheres of radiation.

Someone else who radiates their own special brand of electromagnetism is the pluridisciplinary artist Hiroaki Umeda, who sneaks into the festival program with only a few performances. Bringing two dance works, Duo and ‘while going to a condition’, as well as a short video work, Montevideoaki, Umeda is one of the more exciting prospects in the festival. Watching Umeda dance in ‘while going to a condition’ is like seeing a human oscilloscope, as he builds his movements from Butoh-like restraint into frenetic climaxes. All of this occurs in front of a flickering wall of light and with the audience enveloped by an intensely loud field of electronic crackles and whirs. In Montevideoaki, Umeda’s dance is placed in front of the backdrop of the eponymous Uruguayan capital. The elementary wordplay of the title ought not obscure the fact that it was made in collaboration with Octavio Iturbe, a video artist who has previously made award-winning screen adaptations of Wim Vandekeybus’ choreography.

From the shores of another island-off-the-mainland comes Terra Che Brucia. This Sicilian combination of jazz and projected archival footage is led by saxophonist Massimo Cavallaro. The music fits quite safely into that mode of European electrojazz popularised (and done better) by the likes of Nils Petter Molvaer but the footage itself is a fascinating collection of documentaries on everyday Sicilian life made by Panaria Film between 1948 and 1950, when Italy, especially the impoverished South, was still recovering from the wreckage of the Second World War.

Icelandic Love Corporation, Hospitality

photo Bernhard Kristinn Ingimundarson

Icelandic Love Corporation, Hospitality

One of the more enigmatic forces in Ten Days on the Island will be the Icelandic Love Corporation. This trio of female artists (Sigrún Hrólfsdóttir, Jóni Jonsdóttir and Eirún Sigurdardóttir) produce installed happenings. Walsh met the group in Iceland and invited them to come to Tasmania largely on the basis of the way in which they made coffee. She is gleefully ready to admit that she has no idea what they are bringing to the festival, apart from the title of the show, Hospitality. One suspects there might be a few cups of something involved but the piece will undoubtedly have the wry whimsy that is bred in a country where everyone is related and the banking system has collapsed. You can catch the Icelandic Love Corporation’s particular brand of hospitality at Contemporary Art Services Tasmania in North Hobart for the duration of the festival and a few weeks afterwards.

Ten Days on the Island, Tasmania, March 27-April 5; visit www.tendaysontheisland.org for the full program

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg.

Mahdokht detail, Women Without Men Series (2004)

photo Larry Barns, Shirin Neshat, Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York

Mahdokht detail, Women Without Men Series (2004)

RECENT TALK OF PALESTINIAN “AGGRESSION” IN GAZA, AT A TIME WHEN HUNDREDS OF MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN WERE BEING SLAUGHTERED BY ISRAEL’S HIGHLY SOPHISTICATED MILITARY MACHINE, IS JUST THE LATEST EXAMPLE OF THE ONE-SIDED VIEW WE RECEIVE OF LIFE IN THE MIDDLE EAST. FOR DECADES THE WEST HAS POSITIONED ITSELF AS THE VICTIM OF ISLAM’S SUPPOSED ANTIPATHY TO DEMOCRACY, EVEN AS WE HELP STYMIE POPULAR MOVEMENTS THROUGHOUT THE MUSLIM WORLD. IN THIS CONTEXT, ARTISTIC VOICES FROM THE MIDDLE EAST PROVIDE AN IMPORTANT OPPORTUNITY TO SEE THESE CULTURES FROM THE OTHER SIDE. MIXING MAGIC, TRAGEDY, HISTORY AND POLITICS, THE FIVE-VIDEO SERIES WOMEN WITHOUT MEN BY US-BASED IRANIAN ARTIST SHIRIN NESHAT OFFERS A SHARP REJOINDER TO ONE-DIMENSIONAL IMAGES OF IRANIAN WOMEN AND THE NATION’S MODERN HISTORY.

Neshat’s videos are based on Shahrnush Parsipur’s 1989 magic-realist novel of the same name, set against the backdrop of the US and British-backed coup in 1953 that toppled the secular progressive Dr Mohammed Mossadegh after he nationalised the country’s oil reserves. It was partly her desire to explore this period that drew Neshat to the project. “I found I wanted to return to this historical moment and touch on how the American government had a direct relation to the overthrow of a democratic government, which eventually led to the deep resentment of Iranians against Americans, and indeed paved the road for the Islamic revolution. I had no interest in making a documentary film or an approach that would be a history lesson, but rather I found it interesting and a challenge to build these events as a background to my story.”

Each of Neshat’s videos portrays a female character from Parsipur’s novel, which traces the fate of five quite different women eventually brought together by chance in the city of Karaj, a short distance from Tehran. The videos vary greatly in approach, but none is strictly realist. “Parsipur’s style fit my work perfectly, as she is known for her surrealistic literature…all her work has one foot in society, history and politics, but is also profoundly timeless, philosophical and universal in expression,” enthuses Neshat. Described by the artist as one of Iran’s “foremost contemporary female writers”, Parsipur was imprisoned by both the Shah and the subsequent Islamic regime before fleeing Iran to live in exile in the US.

Neshat’s videos “give a glimpse into the nature of each woman” rather than extrapolating the plot of Parsipur’s novel. “I basically took each woman’s dilemma and tried to reveal her spiritual, psychological, social or sexual issues”, says the artist. “Since each woman’s problems and aspirations were different, I created totally different narratives and stylistic approaches.”

women without men

Mahdokht, the first video made back in 2004, is the most abstract in Neshat’s series. Playing out simultaneously across three screens, it explores the split desires and tormented nature of a young woman terrified by sexuality, yet obsessed with fertility and children. In the novel, the character resolves this contradiction by planting herself in a garden and becoming one with nature.

Although Mahdokht contains striking imagery—notably the crazed central character knitting in a forest strewn with yellow wool—the video is the least successful of the five. The thematic and narrative relationship to Parsipur’s novel is a little too elliptical, and the symbolism too wide open to interpretation. While the other works stand up as discrete viewing experiences, Mahdokht makes little sense without some prior knowledge of the character.

In contrast, Zarin (2005) is a striking horror movie exploring the psychology of a prostitute suffering from anorexia. She is so alienated from her work and her own body that her clients become blank, faceless monsters. In an unbearably visceral scene in a public bathhouse, the young woman attempts to erase her withered frame and sense of guilt through frenzied scrubbing, until she is reduced to chafed, bloodied mass.

Munis, Women Without Men series 2008, Shirin Neshat

courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York

Munis, Women Without Men series 2008, Shirin Neshat

Neshat’s final three videos were completed in 2008. Munis most successfully draws together the novel’s magic-realist style, the videos’ commentary on the lives of Iranian women and the historical backdrop of the 1953 coup. The central character is harangued by her conservative brother as she listens to radio broadcasts reporting unrest on the streets of Tehran. Unable to go outside and participate in the demonstrations, she anxiously paces the rooftop of her home. When she witnesses a fleeing protestor shot on the street below, Munis steps off the roof, engaging in a conversation with the man in their shared moment of death. The video beautifully weaves together her personal tale and the broader historical setting, in a quiet reflection on the frustrated possibilities of Iran’s shattered democracy.

Faezeh unfolds as a nightmare of brutality and ruined happiness. A young woman constantly returns to the scene of her own rape, an indictment of the impossible expectations placed on women to maintain their ‘purity’ in societies that often turn a blind eye to sexual violence.

In the final video in the series, Farokh Legha, Neshat adopts a more realist mode, and once again evokes the ’53 coup as a moment of curtailed possibilities. The middle-aged central character hosts a party in a grand house surrounded by an orchard—a symbol of life and fecundity in an otherwise barren landscape. The party is rudely interrupted by armed troops, some of whom sit down to enjoy a lavish meal while their counterparts hunt down and shoot ‘opponents’ outside.

Some time later, the host returns to her house, now deserted and coated in a thick layer of dust. Discovering a young woman lying prone in a garden pond, Farokh Legha takes her inside, where the girl flickers with life. As the camera slowly pans across the room, the cobwebs fade and flames dance in the fireplace once again. The final image seems to be one of hope, a sign that Iran’s culture, as well as the ideals of the nation’s short-lived democracy, live on despite the traumas we’ve witnessed.

book to video to film

While Farokh Legha marks the completion of the Women Without Men video series, Neshat is currently completing a feature film also based on Parsipur’s novel. Utilising the same actors and Moroccan locations as the videos, the artist says the feature will take a more narrative-driven approach that foregrounds the tale’s historical context.

Part of the attraction for Neshat of a two-stage project lay in exploring the mechanics of storytelling in two quite different environments. “I have been very interested in how the experience of viewing the story may change completely due to the setting—a theatre versus a gallery or museum space”, she explains. “So in my construction and editing of the videos and the film, I’ve tried to address this issue. Once I finish the feature it will be up to the audience to draw parallels and distinctions between art and cinema.”

In exploring Iran’s sexual politics and culture, as well as Western complicity in the crushing of Mossadegh’s government, Shirin Neshat has helped kick open the narrow window through which we typically view Iran in the West. Her videos stand as a provocative memorial to a crucial turning point in the nation’s modern history, and the women who have survived the vagaries of Iran’s political strife. The coming feature promises to be another intriguing thread in the tapestry of images Neshat has woven from and around Parsipur’s fantastical novel.

Women Without Men, video series, director Shirin Neshat, based on the novel by Shahrnush Parsipur; Faurschou gallery, 798 Art Zone, Beijing, China; Oct 25, 2008–March 1, 2009

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 17

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Nicole Kidman, Brandon Walters, Australia, courtesy Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment

TITLING A WORK AFTER ONE’S COUNTRY IS A DESPERATE MEASURE, EITHER BORN OF CAUSTIC CRITIQUE OR BOUND BY PATRIOTIC TRAUMA. THE FORMER CREATES THE PALIMPSEST OF NEGATION WHICH DARKENS ANY COUNTRY’S FLAG AND ANTHEM; THE LATTER IS DEDICATED TO CLEANING, BRIGHTENING AND GENERALLY WHITENING THE SAME. ONLY THE DEAD WOULD MISS THAT BAZ LUHRMANN’S AUSTRALIA (2008) EVIDENCES THE LATTER. YET, UNEXPECTEDLY, I FIND THE FILM TO BE ADDRESSED TO THE DEAD: TO SPEAK TO THE GHOSTS OF THIS THING CALLED ‘AUSTRALIA’ WHO HAUNT THE PSYCHE, THE MEDIASCAPE AND THE POLITICAL FORUM WHICH FORM THE AUDITORIUM FOR VOICING THE NAMING OF ‘AUSTRALIA.’

While leftist-leaning critique of the film has centred on its inaccuracies in Indigenous historicism (which completely misses the hyper-iconic self-mythologizing purpose of Australian cinema in general), Australia offers an ulterior reading in its depiction of racial hierarchy. Ultimately, death haunts the film—particularly in its mega-melodramatic final act where the dream family of Australia’s future is thought to become extinct. There’s probably a White Paper (sic) floating around Canberra’s mindscape that dreams of genetically joining anal uptight colonialism (Nicole Kidman in 100 costume changes) with iconic post-convict machismo (Hugh Jackman at the gym again) with a para-animatronic Aboriginal kewpie doll representation of Indigenous culture (Brandon Walters and his flashing teeth). When they all hug at the end, it was like watching white zombies engaged in an unknowing ritual. I felt an overwhelming sense of how utterly dead Australia is and will likely be for a few millennia still. Australia is thus more a speculative sci-fi about a dying gene-pool attempting to forge a nation according to an inane self-politicising blueprint (not to mention a telling historicist aversion to Asia). The opening and closing statements about the Stolen Generations are less solemn reflections on forced Australian nationhood and more semiotic memes that invert that socio-genetic program within the film’s Hollywoodesque melting-pot of universalising (or market-maximising) story-telling. Like all maximal cultural artefacts, Australia says nothing that it thinks it’s declaring, but volumes of what it cannot hear itself saying.

Australia is neither an embarrassment of glazed nationalistic vulgarity, nor a flailing vision of grand auteur onanism. Sure, it’s bursting with flashy neo-camp affectations inseparable from Australian prerogatives to entertain (c1970s’ camp theatre revues). Sure, it’s driven by a pseudo-PoMo flaunting of artifice (c1980s’ art photography revelling in faux-cinematic tableaux). Sure, its full of dumb journalistic paraphrasing of white guilt and patronising enshrinement of Indigenous mysticism (c1990s’ pre-millennial reassessment of post-colonial politics). But what else should we expect from this film? Indeed—what else does a nation that cried over the bloated pomp of the Sydney 2000 Olympics deserve? And what else should an industry that reads a self-centred magazine subtitled “For Australian Content Creators” require from a $130m movie chowing down on a hefty tax rebate and a financial adrenaline shot by the ATEC (Australian Tourism Export Council)?

The film is inevitably an easy target—but using a narrow-gauge shotgun is an ineffective critical strategy when aimed at the nationalist mirage within which Australian cinema’s self-image has shimmered for over quarter of a century. A wide-spray Uzi handled by a blind drunk is a better tactic. Don’t shoot the film or the filmmakers: shoot the whole context within which they are positioned.

To deride Australia yet engage in polite and earnest dinner conversation over films like Phillip Noyce’s Rabbit Proof Fence (2002), Rolf de Heer’s The Tracker (2002) and 10 Canoes (2006) invokes a simplistic binary reaction typical of the Australian intelligentsia’s support of worthy ideals in ignorance of any semiotic evaluation of the works bearing those ideals. To me, it’s straightforward to view Rabbit Proof Fence, The Tracker and 10 Canoes as humanist universalising, artsy, wannabe-informed examples of post-Mabo cinema at its most obsequious. Australia takes those themes and tizzes them up like a Tivoli burlesque revival. Of course, the film’s core impulse to ‘pizzazz’ an audience is an artistic gesture retrieved from the mouldy stage attire of Reg Livermore and his 70s ilk. Indeed, Australia is like Betty Blokk Buster Follies meets Kevin Rudd’s televised ‘Apology.’ But if that’s what Australians want: give it to them.

Any film that starts with a voice-over telling you that you are about to be told a great and wonderful story is bound to induce nausea in anyone bar script doctors. And despite Australia’s relentless bludgeoning of the senses with its mock-crème production design, mum-look-at-me digital compositing, Venusian fantasy goddess costume design and Australian Tourism’s unending dome of panagliding cinematography, Australia’s foregrounded reflexivity amounts to false genuineness through having a half-breed cute-feral androgyne regurgitate Spielbergian monologues of childhood wonder. Having stated that, I nonetheless find that Australia does effectively compress and express its melodramatic heart, and successfully tugs at the appropriate emotional strings. Ciphers that they are, Kidman, Jackman, Bryan Brown, David Gulpillil, Jack Thompson and Ben Mendelsohn can and are allowed to project précised altruistic ticks of empathetic consonance within the film’s swirling artifice. But—as with Spielbergian templates developed in the first wave of Hollywood revisionism in the mid-70s—the effectiveness of such manipulations merely testifies to how any amassed audience is but a throng of humanised puppets responding to strings tugging their collective heart.

To align oneself with the Australian film industry as a ‘content provider’, a mortgage-paying ‘technician’, or a pithy ‘movie reviewer’ and remain uncritical of the cultural implications of the medium’s multiple crafts is unacceptable. If Australia has a ‘film industry’ then let it be a ruthless industry. Make pornography with girls who look like your first-year-uni daughter. Tell stories about footballers on drugs; bogans killing their kids; Dungeons-and-Dragons nerds massacring tourists. Cast wildly and inappropriately and tabloid the hell out of the production’s sensationalist drive. Write scathing comedies about law students who become topical panellists on national TV and wear chambray shirts; bourgeois ABC journalists who become bourgeois politicians; arthouse distributors claiming to know about cinema. Forget the international market because they care as much about you as you do about Finnish historical drama. Find any niche no matter how unsavoury and exploitatively hammer it to death. Do all this and damn everything that Rudd and his Creative Australia (gag!) think-tank proposed, and Australia will have a real industry—one that would dare its practitioners to stand up for the contentiousness of their work rather than allow them to hide behind the giant phantasmal puff-ball of proud ignorance that spawns gaudy carnivales of patriotism like Australia.

Each year, there’s a polite round-up in the mediascape about ‘Australia’s performance at the box office.’ A successful film receives a disingenuous slap on the back. It sounds like a fly-swatter hitting soggy Weetbix. The ‘worthy’ films that didn’t make a dent in the box office excite a plethora of reasons for their criminal neglect. No-one mentions the possibility that the films were simply not interesting as concepts in the first place. The upcoming year’s roster will be optimistic, and articles like the one you’re reading will be posed as ‘part of the problem not the solution.’ Yet those upcoming films will smack of the same insular ‘Aussifying’ themes which smell like state theatre company ‘finger-on-the-pulse’ productions or social studies curricula foisted on Year 11/12 inmates.

This may seem completely off-topic. Wrong. The context which creates then evaluates the likes of Australia is the problem. If all the other forms of alternative non-nationalistic exploitation were allowed in the industry, then Australia would simply be another option for entertaining an audience. And at such a chosen task, the film completely succeeds. What’s missing is all those other films. (Written on Australia Day.)

Australia, director Baz Luhrmann, writers Stuart Beattie, Baz Luhrmann, Ronald Harwood, Richard Flannagan, cinematography Mandy Walker, editing Dody Dorn, Michael McCusker, production design Catherine Martin, 2008

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 18

© Philip Brophy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

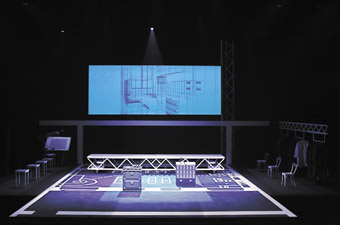

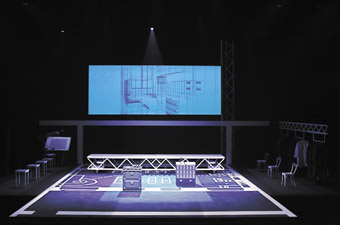

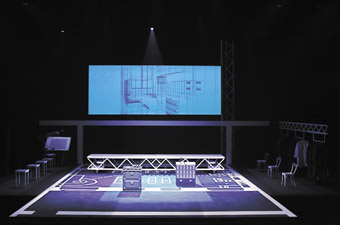

Australia exhibit, Setting the Scene, photo Nolan Bradbury

THE AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR THE MOVING IMAGE’S EXHIBITION SETTING THE SCENE: FILM DESIGN FROM METROPOLIS TO AUSTRALIA SHATTERS THE CINEMATIC ILLUSION TO UNCOVER THE IMPACT OF ART DEPARTMENTS, FILM ARCHITECTS AND SET DESIGNERS ON THE HISTORY OF CINEMATIC STYLE. THIS EXHIBITION EXPLORES THE PROCESSES OF CREATION IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF ILLUSORY SPACES AND REVEALS HOW AESTHETICS INFLUENCE TONE, MOOD AND ATMOSPHERE IN THE CINEMA.

Setting the Scene is based on the Deutsche Kinemathek’s Museum für Film und Fernsehen exhibition Moving Spaces: Production Design + Film. The German and Australian curators collaborated to develop a series of diachronic “spatial constellations”, emphasising the evolution of art design and the impact of old and new technologies. ACMI’s exhibition is organised into interrelated zones including: Spaces of Power, Private Spaces, Labyrinth Spaces, Transit Spaces, Stage Spaces, Virtual Spaces and Location Spaces. What emerges is a heterotopia of design with more than 300 exhibits of still and moving images, concept artwork, storyboards, computer visualisations and scale models that coalesce and collide, producing dynamic contrasts and connections by prioritising art design.

The Spaces of Power constellation illustrates the signification of control in the depiction of vast spaces, minimalist design, monumental architecture and access to vision. This area is dominated by a large film still showing the prodigious elevated office designed by Erich Kettelhut for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927). The graphic symmetry of the gigantic window combined with heavy furniture supporting futuristic communications technology renders Jon Fredersen (Alfred Abel) a God-like figure, able to survey and control the city. Images of the subterranean war room set for Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) display a space filled with screens showing maps the size of walls, extending the connection between power and magnitude into the realm of parody. Both upper and lower spaces are constructed for surveillance and to inspire paranoia through cinematic revisions of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon.

While these images are striking examples of control built from monumental set design, one of the smaller artefacts included in Spaces of Power reveals how illusions of entrapment can be created in miniature. A glass box protects a small set built by the production designer Herman Warm for Robert Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919). This model is the location of the prison scene, its black background with parallel white lines descending towards a spot on the floor are used to direct the eye to the hypnotist/murderer and to radiate a sense of his torture. This exhibit also underlines the influence of the German Expressionist visual style with its high contrast, painted light and shadows, absurdly dysfunctional architecture and its cities built on jagged lines.

The first screen of the Private Spaces zone features a scene from Jacques Demme’s recitative musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Demme’s art director Bernard Evein and costume designer Jacqueline Moreau collaborated to develop scenes based on a specific colour palette. The design of wallpapers and fabrics complement costume, resulting in a visual style so inextricably bound to mood and tone that textures become as expressive as characters. In one scene blue floral wallpaper in the bedroom seems to imply that Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve) sleeps in a watery interior garden. A scene from Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle (1958) shows a neighbour touring the sterile, empty spaces of the villa Arpel, teetering across the concrete floors on her stilettos, barely able to sit on the furniture which exists for its design, not for comfort. This dysfunctional modernism barely conceals the social critique created by Jacques Lagrange’s spatial design and inherent in Tati’s cinema. The exhibition includes a model of the candy coloured modernist cube house with its obsessively manicured garden surrounding a giant fish water sculpture. The model has buttons that tilt a garage door open and animate a terrier in a tartan coat.

Research photographs, film stills, sequences and a model of the maze from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) are the most compelling aspects of the Labyrinth Spaces constellation. In Kubrick’s film, the Overlook Hotel is transformed into a site of terror with labyrinthine corridors carpeted in alarmingly contrasted colours, elevators filled with gushing blood and hallucinatory images of decay and death behind the doors of hotel rooms. Ray Waller’s production design reveals how cinematography and Steadicam can be used to insert a gliding spectral presence in interior and exterior mazes. Dante Ferretti’s film design, inspired by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi, is also exhibited here, with production photographs and a wooden model of his staircase leading in all directions, but ultimately nowhere, from The Name of the Rose (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1986).

Transit Spaces become visual signifiers of Marc Augé’s notion of “non-place.” Steven Spielberg’s The Terminal (2004) is filmed on a bespoke, full-sized airport terminal set built by Alex McDowell and including escalators, elevators, furnishings and 35 retail franchises. Spielberg used a periscope camera to check camera angles. The airport terminal set is a heightened non-place, its depersonalised sites of transience and anonymity emphasise movement rather than stillness. Such a transit space becomes a home for the protagonist. A model of the set, sequences from the film and interviews with the production staff reveal the film’s base in the story of the Iranian refugee Merhan Karimi Nasseri (aka Sir Alfred) who was condemned to live in a Parisian airport for 10 years.

Whilst the 1.5 scale model of the Mach 5 car in Speed Racer (Wachowski, 2009) looks like a toy, it represents the zenith of futuristic set design. For this film the Wachowski brothers and their production designer, Owen Patterson, used “virtual cinematography” to create “reality bubbles.” Curator of Setting the Scene, Kate Warren, explains that Speed Racer’s composite spaces were built from digital images of locations including Italy, Morocco, and Death Valley. These panoramas were then stitched together, manipulated and composited resulting in the creation of an artificial global space that is both everywhere and nowhere.

Australian art directors have high profiles in Setting the Scene. The highly stylised visual aesthetic developed with Tracey Moffatt by Stephen Curtis on studio sets for Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1989) and beDevil (1993) created surrealist inspired hyper-stylised landscapes. But some of the most striking images are shot on location, using few visual effects. A montage of research photos of post-apocalyptic locations shot by Chris Kennedy reveals images of New Orleans post-Katrina, Mount St Helens, mines in Pittsburgh and a deserted theme park in Pennsylvania, all preparation for The Road (John Hillcoat, 2009, based on the Cormac McCarthy novel of the same name), a film yet to be released in the cinema.

All paths in Setting the Scene lead to the showcase exhibit, Baz Luhrmann’s Australia (2008). This constellation includes topographic maps and interviews with art director Catherine Martin describing her initial ideas for the design, the impact of the landscape and the ways that design signals a narrative turn and implies cultural change. The most imposing and intriguing exhibit in Setting the Scene is the living room set of Faraway Downs, a key location for Australia. The set has been recreated specifically for ACMI’s exhibition and the visitor can peer into the domestic space and see the combination of European influenced heavy leather furnishings and pristine cut glass decanters sitting alongside woven baskets, boomerangs and bark sculptures. In Australia, visual design enables a subtle shift towards the inclusion of Indigenous cultures.

Setting the Scene provides a heterotopia of visual design constructed from an array of art and artefacts representing disparate times, spaces, ideas and possibilities. This exhibition highlights the visual affect, privileging the pathways, networks and rhizome-like connections between contemporary art direction and visual styles of the past and the future. With Setting the Scene, ACMI has curated a dynamic archive of the work of local and international art directors, revealing film design to be a radically evolving art form.

Setting the Scene: Film Design From Metropolis to Australia, Australian Centre for the Moving Image in collaboration with Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek, Museum für Film und Fernsehen, Berlin; Melbourne, Dec 4, 2008-April 19, 2009

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 19

© Wendy Haslem; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Laila’s Birthday

CULTURAL MEDIA’S MISSION IS TO STRENGTHEN INTERCULTURAL UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN DIVERSE AUSTRALIAN COMMUNITIES THROUGH THE PROMOTION OF ARAB ARTS AND CULTURE. THE FIRST PALESTINIAN FILM FESTIVAL, A NEW INITIATIVE FROM CULTURAL MEDIA—A NOT FOR PROFIT ORGANISATION ESTABLISHED IN 2007—SCREENED OVER TWO WEEKENDS IN DECEMBER AT PALACE NORTON STREET CINEMAS AND SIDETRACK SHED THEATRE IN MARRICKVILLE. IT DREW LARGE, DIVERSE AND ATTENTIVE CROWDS WHO DEMONSTRATED THAT THERE IS INDEED A GREAT HUNGER FOR MORE OPPORTUNITIES TO ACCESS AND ENGAGE WITH PALESTINIAN LIFE AND CULTURE.

The program showcased a broad spectrum of films ranging from six acclaimed feature films to independent documentary production and university sponsored educational materials. The feature film with the highest profile was Annemarie Jacir’s Salt of This Sea. It had screened in Un Certain Regard at the Cannes Film Festival in 2008, was Palestine’s 2009 Academy Awards submission for Best Foreign Language Film and has won a number of awards at international festivals.

Shot in Palestine under difficult conditions, Salt of This Sea follows Brooklyn born and bred Soraya (Suheir Hammad) as she lives the dream to return to Palestine, from which her family was exiled in 1948. Stubbornly trying to reclaim her grandfather’s savings, frozen in a bank account in Jaffa when he was exiled in 1948, she is slowly taken apart by the reality of Palestinian life around her. She meets Emad (Saleh Bakri), a young man whose ambition, contrary to hers, is to leave his home in Palestine forever.

The other fiction feature film in the program, Laila’s Birthday, directed by Rashid Masharawi, follows a complicated day in the life of Abu Laila (Mohammed Bakri) an unemployed judge currently driving his brother-in-law’s taxi to make ends meet. His quest to get a present and a cake in time for his seven-year-old daughter’s birthday is constantly interrupted by surreal, sometimes comic events.

This film captures the streets of Gaza through the windows of Abu Laila’s taxi. The conversations with passengers, and the ordeals to which the taxi is submitted, capture the state of affairs in the territory in all their absurdity and poignancy. Each unpredictable daily difficulty cumulatively begins to wear on Abu Laila, unbeknownst to those he encounters, who continue to make their insistent demands. He finally cracks as he waits for his taxi to be refuelled, unleashing a tirade through a megaphone wrestled from him by its policeman owner. Returning home, Abu Laila finds peace as his daughter giggles at the state of his taxi, accidentally decorated for a wedding during the course of the day’s many events.

On a different note, Reel Bad Arabs and Edward Said on Orientalism, both directed by university professor Sut Jhally, were built around interviews with the authors of significant books on the representation of Arabs in the West. Both films provided sophisticated discussion about the politics of representation. The publication of Said’s Orientalism in 1978 resulted in major shifts in contemporary thought, still reverberating around the world today. However, although Said talks here about the context in which his argument was first conceived and extends his discussions of the concept of Orientalism to media representations, the film shows its age and does not extend the late writer’s insights to the contemporary political situation subsequent to his death.

Sut Jhally’s other film is based on the book Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People, written by Jack Shaheen, Professor Emeritus of Mass Communication at Southern Illinois University. The video successfully integrates interviews with Shaheen and clips from myriad movies ranging from blockbusters featuring the likes of Arnold Schwarznegger right back to some of the earliest representations in the history of cinema—an excellent companion piece to Said’s Orientalism.

Sling Shot Hip Hop

The most talked about film of the festival was Slingshot Hip Hop, directed by Jackie Reem Salloum. This unique documentary deftly intertwines stories of young Palestinians living in the West Bank, in Gaza, in refugee camps and inside Israel as they discover the power of hip hop as a tool for self-expression and cross-border communication.

Slingshot Hip Hop traces the origins and development of hip hop amongst two distinct groups, one located in the West Bank, the other in Gaza, its members young, male and female, who initially struggled against Israel’s stringent travel restrictions to meet each other. That was until they gained the support of an organisation promoting youth development projects across Palestine. These groups build hip hop into an educational tool to teach young people, to provide an outlet for self-expression and connectedness, which throughout the film is voiced in entirely non-violent terms. After the recent devastating attacks on Gaza, no doubt many who saw the film will be worried about the current circumstances of the young men and women from the group, whose stories imprinted themselves so strongly.

Writers on the Borders: A Journey To Palestine(s), directed by Samir Abdallah and Jose Reynes, likewise travelled across Palestine following artists and storytellers. It documented the journey of eight writers from the International Parliament of Writers who travelled to Palestine to visit renowned poet . Darwish, who could not leave his own country to attend their international festivals. This film continues Cultural Media’s focus on Mahmoud Darwish, following an event celebrating the life and work of the Palestinian poet at the NSW Writers Centre in October 2008.

Writers on the Borders incorporates the diverse perspectives of the international writers on the trip, each of whom muses on their experiences of Palestine in an impressive array of languages. This is integrated with readings by Darwish and others at events set up throughout the film and exciting to witness. Relentless in its documentation of almost every detail of the delegation’s journey, Writers on the Borders also successfully produces a series of intense eyewitness accounts of Israel’s ongoing, systematic project to devastate and disrupt the everyday lives of ordinary Palestinian people. It provided a useful context for understanding the relentlessness of Israel’s most recent attack on Gaza. Among many injustices, the writers encounter roadblocks designed to prevent access to universities and homes and farmland freshly bulldozed to make way for the ever-expanding Israeli incursion into Palestinian territory. Such details tend to make it to our television screens only in times of crisis.

The Palestinian Film Festival successfully brought together a diverse array of people to share many different encounters with Palestinian life. Let’s hope it becomes a regular event on the Sydney screen culture calendar and has the opportunity in the future to travel to other parts of Australia.

2008 Palestinian Film Festival, festival artistic director Sohail Dahdal; Cultural Media, Palace Norton Street Cinemas, December 5–7; Sidetrack Shed Theatre, December 13–14

RealTime issue #89 Feb-March 2009 pg. 20

© Megan Carrigy; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Seed Collective, www.seedcollective.org

photo Gabe Sawhney

Seed Collective, www.seedcollective.org

THEY’RE IN OUR POCKETS, THEY’RE IN OUR HOMES, IN OUR CARS, AND THEY’RE ALL AROUND OUR URBAN ENVIRONMENTS. IT’S HARD TO THINK OF A METROPOLITAN EXPERIENCE THAT ISN’T THOROUGHLY OVERLAYED AND INTERLACED WITH A HUGE VARIETY OF DIFFERENTLY SCALED SCREENS. THIS IS WHAT FIRST CAUGHT MY EYE AND LED ME TO ATTEND THE URBAN SCREENS EVENT IN MELBOURNE AT THE START OF OCTOBER 2008. HOW DO WE DEAL WITH ALL THESE IMAGE SURFACES AND NETWORKED DISPLAYS THAT TYPIFY THE PRESENT GLOBAL PUBLIC SPHERE?

When we think urban screens (as opposed to sub-urban, ex-urban or non-urban ones?), we typically conjure images of oversized projections strangely attached to Gehry-like buildings in hypermodern CBD plazas. Think Seoul. Think Times Square. Think Fed Square.

While the Bladerunner-scale of the moving image takes hold of our imagination and tends to hog centrestage, Urban Screens Melbourne 08 took a broader and more expansive view of the spatial impact of screen technologies in contemporary culture and cities. Urban screens can be seen as providing a new digital layer to the city, an augmented media space that folds and flexes its way into and out of contemporary urban experience. It was the event’s engagement with this broad field that made Melbourne’s Urban Screens 08 such an engrossing and stimulating event.

The third in an ongoing series of international projects (the first was held in Amsterdam in 2005 and the second in Manchester in 2007; RT84, p30), the Melbourne program focused its conference and related events around the theme of “Mobile Publics.” Consisting of a series of keynote addresses, panels and discussions, the conference provided a framework for the presentation of a wide variety of media works presented in public urban contexts. This multimedia program was developed by Mirjam Struppek, who was one of the originators of the Urban Screens conference in Europe, and a founding member of the newly established Urban Screens international network. The Mobile Publics Conference was jointly developed and presented by Scott McQuire, Nikos Papastergiadis and Sean Cubitt from Melbourne University’s School of Culture and Communication, and set the intellectual scene for the event as a whole.

It could be argued that Fed Square houses one of the most successful implementations of a large screen in a public mall/piazza space. Filling up an entire city block, the square was purpose-built in 2002 as a public meeting place for Melbourne. As Kate Brennan (CEO of Federation Square) noted in her opening remarks and comments during later discussions, the Fed Square screen has been programmed by the authorities/managers of that space at the same time as it’s been claimed by the general public. We see this most clearly in the public assemblies and displays of mass emotion around major sporting events and significant moments in our collective political and social history—witness the crowds around this and other large public screens for the Prime Minister’s Apology.

But does this mean that these outdoor screening spaces are appropriate for contemporary artists and media makers? Through the multimedia program, film screenings and joint broadcasting initiative, curator Struppek strove to engage audiences in the social/technical space of the Fed Square environs. This extended from the main 65-square metre Barco screen in the outdoor plaza to numerous indoor and outdoor public LED screens, interactive ticker screens and temporary projection installations. The scale of the programming, and the scope of the works was impressive, though ultimately impossible (for this reviewer at least) to see it all.

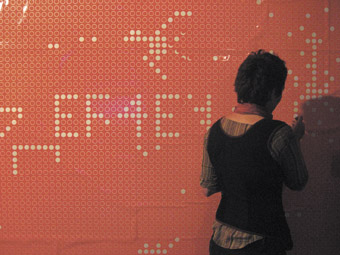

The large screen space was used to engage passersby in contemporary interactive works such as MobiToss—MobiLenin by Jurgen Schelble from Finland, SEED by Canadian artists Napoleon Brousseau, Gabe Sawhney, Galen Scorer, Dave Reynolds and Adam Bacsalmasi, and Troy Innocent’s x-milieu abstract interactive installation.

This context and curatorial strategy for works presented in Melbourne is not at all like the infamous SPOTS media façade in Berlin which began showcasing large-scale interactive artworks in 2005. Although this ‘screen’ and others of its kind in Europe were (for some time at least) devoted exclusively to electronic art and experimental/alternative content, the standard large TV format of Fed Square provides a very different, and arguably more difficult set of constraints for artists to work with. Many of the attempts I witnessed to involve the public in this kind of interactive engagement were not particularly successful, and highlight the complexity of making urban scale works that connect with ‘random’ publics.