Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

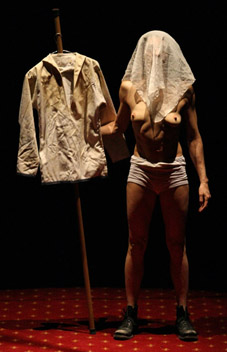

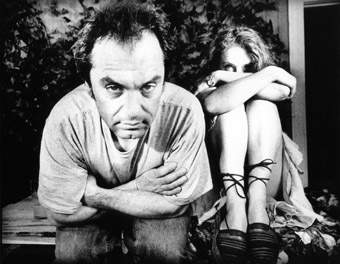

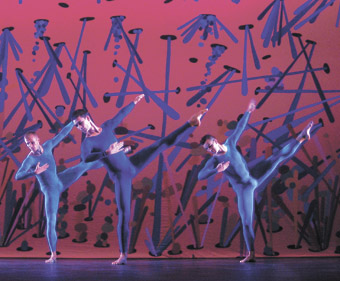

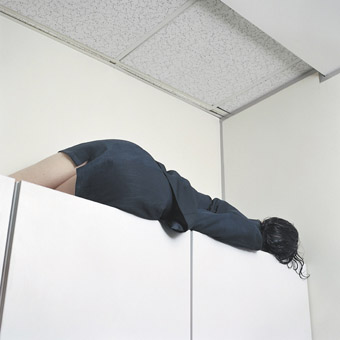

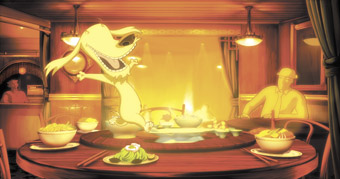

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

photo Tim Matheson

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

The challenge any playwright faces is how to make their work robust enough to survive the potential vagaries of production. It requires making strong choices that will support a clear vision. Drawn from the writings of a young activist killed in Gaza, My Name is Rachel Corrie is far from a traditional play text. The process of turning Corrie’s journals and e-mails into a script is credited to the editors Alan Rickman and Kathleen Viner. Editing is an alien concept to theatre where the preferred term is dramaturgy, a process which includes an exploration of how the text will operate in performance. If Corrie’s voice survives this translation process, it is because of the performative quality of her journal writing and the chatty, informality of her e-mail style. Corrie was a gifted writer. Beautiful evoked images – salmon swimming underneath the streets of Olympia – alternate with affirmations that have Hemingway -ike economy: “I want this to stop”. Despite these strengths, this is fragile material that needs to be handled delicately.

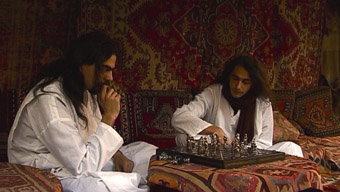

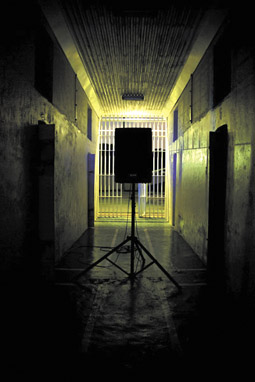

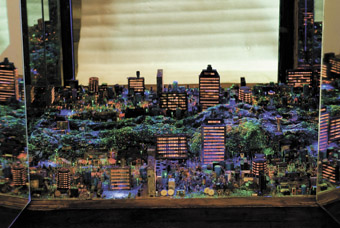

The Havana is a small black box theatre located at the back of a restaurant on Vancouver’s eastside. It has never looked so gorgeous. The space has been completely cleared, with a single row of seating running around the four walls. Above the seating are wall-length rectangular projections. When the audience enters, cuttings from newspapers telling of Corrie’s death are projected. The texts overlap making them difficult to read. During the show, the projections are mostly colours and abstract designs until Corrie arrives in the Middle East, at which time we see photos of cityscapes and destruction. In the centre of the space a white square is boldly defined on the black floor. Within the square there is an office chair and an indefinable piece of ugly office furniture which acts as a table. The space looks futuristic and very tidy. Resting on the table is a white Mac Book computer, a model unavailable in 2003 when Corrie was killed; an early clue to the distancing artifice that informs the production.

The performer, Adrienne Wong, greets the audience as they come in, introducing herself to strangers. If she knows you, she greets you by name and spends a few moments catching up. When the show is ready to start, Wong goes to the entrance, where two more Mac Books glow stylishly in the darkness. She closes the door and does something with the laptops, giving the impression that she’s running the show with them. She makes her way to the performance space, takes off her shoes and then – accompanied by a suitable jet-like sound and lighting effect – steps onto the white square. She never leaves this claustrophobic space, except for one stylized moment where she follows a lighted path around the square. The rest of the time, Wong moves restlessly around the space engaging with the audience, making direct eye-contact.

It’s worth describing the production in this much detail. I will long remember the stylish presentation but not, alas, Corrie’s words. This is a production interested in the artifice of performance. The implication is that we should never believe Wong is Corrie and I never did. Rather, she is Wong performing Corrie’s words. Perhaps the producers, neworld and Teesri Duniya Theatre, were concerned about mimicry and felt this was a more sensitive approach to remembering Corrie. Unfortunately for me the artifice was simply too heavy. Wong’s entrapment within the white square is too distracting, even the projections take us too far from the words. This is not a traditional script with a coherent narrative structure that can support all the weight the production throws upon it. It is too fragile.

Wong is a charismatic performer who commands attention but even she struggles against the artifice. She gallops restlessly through the script at high speed. Perhaps this is meant to evoke Corrie’s youthful energy but it came across to me as a lack of faith in the material. It meant that her performance wasn’t as nuanced as it should have been and came off as too one-note. The one moment where things did slow down – an e-mail exchange between Corrie and her father – suddenly brought the production to life.

Corrie was a list maker and lists are featured repeatedly throughout the text. List-makers try to impose some form of order on a chaotic world. It is ironic that the over-determined nature of this production overwhelms Corrie. Her writings demonstrate the passion and emotion that drove her, yet this production generates a cool, intellectual distance. Perhaps this was a response to the controversy that has dogged this play (protests took place in New York and Toronto over the play’s sympathetic depiction of the Palestinians). While rationalism is laudable in the face of polarised debate, it seems untrue about what we know of Corrie. With the audience able to see each other, with Wong making direct eye-contact there is a form of calculated intimacy but it was with the performer and not the text or with Corrie herself.

Rachel Corrie was a vibrant individual seeking a role in the world and an identity that would suit her passions. Despite her strengths, her fragile body was too easily destroyed. I wish this production had relaxed its intellectual guard so that we could glimpse more of the fragile beauty of the script and the emotional power of Rachel’s story.

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

photo Tim Matheson

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

The actor shakes every person’s hand as they walk into the small, square Havana Theatre. “Hi, I’m Adrienne Wong.” The gesture invites you personally and a few minutes later, when Wong launches into My Name Is Rachel Corrie, you realize she’s set up an intimacy that she’ll develop as the play unfolds.

In fact Teesri Duniya Theatre (Montreal) and neworld theatre (Vancouver) have taken care to build intimacy into every part of the show. The performance is in the round but there’s only one row of about twelve seats along each wall, so every sight line is direct. The set is functional: a thickly upholstered white office chair and a skinny white one-legged table, both on wheels, a white laptop computer, and a white square of light projected onto a white vinyl square taped to the floor. Narrow horizontal screens hang above each row of chairs; the initial projection is a collage of headlines about the death of the young American peace activist killed in Gaza in 2003 along with excerpts from her emails. It’s all pared down and it’s all around you all the time.

Pacing the stage, or swirling in the chair, Wong swivels every minute or so to address all of the audience. At some point she will look at you, and you know she’ll do it again. It’s not invasive, it’s engaging, and it brought me into the story almost as if it was a conversation.

Directness shapes the evening profoundly. The play is constructed from Corrie’s metaphor-filled, descriptive emails and letters (compiled by UK actor Alan Rickman and Guardian journalist Katharine Viner in 2004-05). Corrie was a skilled, nimble writer but the words were originally meant to be read, not spoken. Wong’s eye-contact and restless movements give them a convincing physicality. And the straightforward, person-to-person approach cuts through the thick layer of controversy that surrounds this work – polarized opinions, cancelled productions in New York and Toronto, and the difficult facts about Corrie’s death and Gaza Palestinians’ ongoing lack of reliable access to water, housing and food. When Wong/Corrie looks right at you, the question is: what do you feel, what do you think? It’s a powerful way to handle what has become such a locked-down story.

And this is what usually gets lost in debate about this play. A substantial chunk of it is about Corrie as a person. We meet her as a pre-teen, then in high school, then college, before she feels the pull to try and understand personally a complicated part of the world. Her young voice is endearing and funny. One day she goes for a walk in the forest and sings Russian drinking songs to the trees. She describes walking home late at night in “slutty boots” thinking about the salmon who, thanks to modern city life, have to swim back to their birthplace through culverts since that’s where the streams are now diverted. “It’s hard to be extraordinarily vacuous when you always have salmon in the back of your mind.” These are simple, almost innocent thoughts that show a mind growing.

The play reveals the context of Corrie’s activism. As she learns, organizes and joins events, like walking down the street with forty other people dressed as white doves, her voice alters. She wants to know what happens on the other end of US tax dollars in places where that massive military budget is being spent. She’s angry but humble. After she arrives in Gaza, to work with the International Solidarity Movement to watchdog against events like water wells and greenhouses being bulldozed, she retains that sense of probing. She never sets herself up as an expert: “I am new to speaking about the Israel-Palestine conflict so I don’t always understand the political implications of what I am saying.” She’s just a person trying to figure out what’s going on. She notices glow-in-the-dark stars in blown-out bedrooms; she’s disturbed when closed checkpoints prevent Palestinian workers from going to, or returning from, their jobs. The play doesn’t become didactic; it offers information and opinion, and asks us to form our own thoughts.

Wisely, Corrie’s death is not enacted. Completing her moments as Corrie, Wong puts on a bright orange safety jacket, reads aloud her last email to her mother (about two men offering her a meal), and steps off stage. A moment later, she takes off the jacket and activates two small-screen videos in which a young man describes how the bulldozer moved toward, then over, Corrie. It’s the right amount of detail: facts are involved here, and no one pretends to know them all.

My Name Is Rachel Corrie is a story about how a person grows to look outside her own life and tries to grapple with huge, traumatizing events that she knows she can walk away from at any given moment, even though the people living there can’t. Corrie’s convictions about justice, compassion and activism led her to Palestine, but those beliefs can be applied to other injustices in the world. Journalists, activists, immigrants and others in areas torn by military conflict talk about having to make difficult choices on a regular, sometimes daily basis. Can the rest of us learn from their experiences, or are they too distinct from ours? And, thinking of Corrie’s death specifically, aren’t there any insights from her story that reach beyond the specifics of the Israel-Palestine conflict?

Like the square of light that widened and shrank around Wong as she moved through expansive or frightened, tightened moods, the play can open out or close down our ideas if we are willing to take that first handshake for what I think it was: an invitation to hear one real person tell another real person’s story, respecting us, too, as individuals with so much to learn.

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

photo Tim Matheson

Adrienne Wong, My Name is Rachel Corrie

When Rachel Corrie (Adrienne Wong) takes her special needs clients from a resource centre out for a treat at the Dairy Queen in Olympia, Washington, she wants them to practise their social skills. The trip degenerates quickly as the solo actor recounts it, standing on a white square in the middle of the room. Rachel’s clients cry and fight, and have to be given a long “time out”, during which their ice creams melt and make a mess of the table. Rachel practices her counseling skills on them – skills so new and deliberate they haven’t become part of her yet. “I’m grounded in my personal space,” she tells the audience, as she urges her invisible clients to do some deep breathing. Instead they get “very escalated.” Eventually she loses her cool completely and tells them they will never get to go to Dairy Queen again. She’s had zero positive effect on her clients that day, but Rachel Corrie is a woman who still believed she could have an effect on the world, and she turned out to be right.

My Name is Rachel Corrie has two goals. One is to let us better know Rachel Corrie, who was killed in Rafah in 2003 when she stood in front of an Israeli bulldozer trying to demolish a Palestinian home. The other goal is to let us better know the situation in the Gaza Strip.

Rachel Corrie comes across as a profoundly serious woman who rarely indulges in the playful self-mocking of her Dairy Queen story. At first her words reflect the powerful influences of youthful self-absorption and activism. She speaks of “doing progressive work” on “anti-war slash global issues”, and informs us that she “tries to be local. That’s a big part of my ethic.” When later given the chance to leave Rafah and go to France, she writes that she would “feel a lot of class guilt.” The words are genuine Rachel Corrie – they come from Corrie’s own emails and journals – but they were meant to be read, not to spoken, and it’s hard to hang a play on their formal sincerity. There’s no doubt this is how an intelligent, passionate, political young woman would write, the kind of woman whose boyfriend reads anarchist works, the kind of woman who finds out that a salmon creek has been funneled into an underground pipe in downtown Olympia. “It’s hard to be extraordinarily vacuous when you always have salmon in the back of your mind.” But it’s not how this same young woman would speak to us directly, and there might have been more imaginative ways to adapt the original material.

An additional difficulty is that, in Wong’s delivery, Rachel’s emotional highlights are almost always based on political outrage. The director has also set the pace of the play very fast, and it feels relentless. The set compounds the sense of small range. Rachel only moves in the cramped white square on the floor, set with a chair and a table on wheels. She never steps outside the square, except when the lighting design adds a narrow grey pathway around it, and she treads that carefully. Rachel lives in a world she sees very clearly. Her sense of right and wrong is almost religious. Her certainty fuels her activism – it takes her to Gaza to see how she can help. People who tread the grey pathways more often would never buy the ticket.

At first she benefits from the trip. In Palestine, her language changes abruptly. It’s less inflected with stock liberal phrases, less about herself and more about the world around her. She becomes more real to us. And yet she still prefers to say, “I am scared for these people.” It takes a very long time before we hear her admit, “I am scared.” In fact one of the most poignant moments comes from her father instead. He writes her to say he is proud of her, but “I would rather be as proud of someone else’s daughter.” They are simple words and simple emotions, and they carry.

Rachel ploughs and re-ploughs the same white square, perhaps now the safe space of her own privilege as an American citizen, as she tells us what she experiences in Rafah. Long narrow screens on all four walls show us horizontal images of rubble, and walls pocked with bullets. It’s the first time we see representational images on the screens, as if coming to Palestine has been our first glimpse of the real world. But she never refers to any Palestinians by name, and even her fellow volunteers she calls “the Internationals.” Rachel is so focused on the power structure that everyone is identified by their position in it, rather than by their own identity. Although we see, and honour, her commitment, although we learn more about the daily struggles for normal life in Rafah, and although we share her sense of wrong, the window she opens for us in the Middle East always feels like a narrow one, just like the projections on the wall. The narrowness isn’t due to a single point of view. That’s all any of us would have to offer.

It’s important that we get to see plays like My Name is Rachel Corrie, even if limitations in the scripting and direction detract from the potential power of the story. But few among us will go abroad to witness first hand the results of our country’s foreign policy, as Rachel chose to do. The play asks us: what might happen if we did?

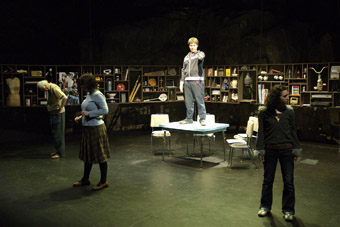

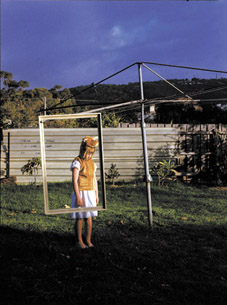

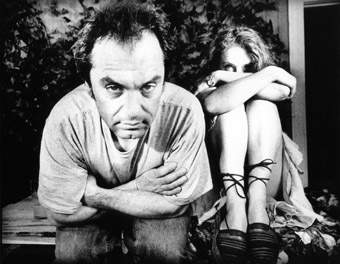

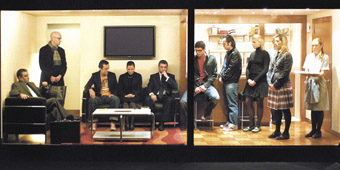

Dov Mickelson, Tim Machin, Sarah Machin-Gale, Nancy McAlear, Frankenstein

photo Photomagic

Dov Mickelson, Tim Machin, Sarah Machin-Gale, Nancy McAlear, Frankenstein

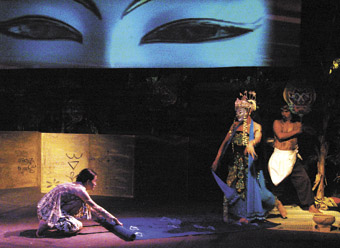

Any adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has to contend with the potency of the original story. The idea of a man so enthralled with his own brilliance that he pushes beyond the bounds of the natural order still resonates because of our unease over genetically “improved” fruit and veg. The horror is realised when man’s unnatural creation comes to life and starts to extract its demands. The central relationship in the Frankenstein myth (and it has achieved that status) is between creator and created. I also wonder if the story, as envisaged by Shelley, represents the fear of childbirth and what happens when the child we create becomes a monster. The horror of Frankenstein’s creation should be bloody and visceral. It should be muddy and dark.

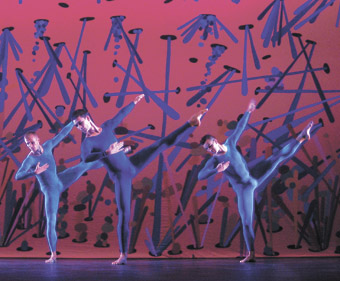

Muddy and dark are the last thing we get with this Catalyst Theatre production. Instead we get a world of white, a world of strange organic shapes that reminded me very much of the drawings of Dr Seuss. The costumes, in particular, are striking with wild hats, eccentrically shaped dresses and bizarre dreadlocks. Paper was somehow involved in the creation of the costumes and set and so everything – and I mean everything – has the texture of crumpled paper. When lit with a rich colour scheme, the costumes look beautiful but somehow they irritated me. They looked too moulded, too constrained and uniform – even the monster is bizarrely made of the same stuff. Perhaps all this rumpled white is meant to put the audience in mind of a paddled cell.

If so, Jonathan Christenson, writer, director and composer wants to take us into the madhouse and the seemingly endless parade of characters we are introduced to (each with their own song) are meant to be inmates. But if everyone is crazy, if the world is a madhouse, then how are Victor Frankenstein (Andrew Kushnir) and his creation (George Szilagyi) any different and, crucially, how does this decision support the central themes of the work? Both are outsiders. They represent the unnatural capacities of man set against natural order. Having these two iconic figures lost amongst the paper lunacy is simply baffling. The only way to make this set up work would be to have the creature appear both sane and beautiful. What we really needed was Brad Pitt in a well-tailored tuxedo. Instead we get another nutter in a paper suit. The only difference is that he’s wearing a cowboy hat and his face is wrapped in bandages.

It’s not just white paper that Victor and his poor creation are lost in; they are also lost within the narrative. The most glaring example is the creation scene. There is none. Victor trots off to university wondering how life is created and why people have to die. He’s spurred into these thoughts by the loss of both parents. Yes, once again a madman is created by childhood trauma. Oprah Winfrey has a lot to answer for. The next thing we know, folk in the university town are singing of disturbing rumours about young Frankenstein. His housekeeper Nancy McAlear – channelling Madeline Khan from Young Frankenstein – keeps them at bay. Next thing you know, Victor creates a monster, with the help of some magical books! In his room! We know there’s a monster because we glimpse a pair of long clawed hands through a gauze screen. A narrator also pops up to tell us. I have to admire Christenson’s courage. Most theatre artists would have focussed on the bloody creation itself. We would have seen Victor consumed with madness as he neared his goal. We would have been drawn in, made complicit, as the creature begins to breathe, to move. Maybe Christenson didn’t want to get blood on the delicate costumes. Instead of all that gruesome nonsense, we get a courtroom scene.

The woman on trial is Victor’s nanny. She stands accused of killing Sweet William, Victor’s adopted brother. Three locals sing lengthy testimonies and, in the interest of fairness, the accused gets to respond to the charges in turn. The court case lasts so long that by the end I was beginning to believe she was guilty. Of course she isn’t. Sweet William was killed by Victor’s monster. We know this because Victor, in any earlier scene, had deduced who the real culprit was. In any event, Victor stands by and looks anguished while his surrogate mother is found guilty. We don’t actually see the hanging, of course, which considering what we had to sit through is a bit of a let down.

The Sweet William murder scene is told again in the second act, this time by the monster with the help of ever present narrators. We don’t see the murder, of course. The monster describes it while William appears upstage behind the gauze curtain. In fact the monster’s whole story, from departing the university town to reunion with Victor years later in the mountains of cling-film, is told in flashback. I stress “told”. The monster tells his story downstage while the characters he encounters appear upstage again behind the gauze of memory. This format is only broken once that I recall when he encounters a blind fiddler, a scene which unfolds in real time with two actors talking to one another. You have no idea how refreshing this moment was.

For some unfathomable reason, Christenson employs a team of narrators throughout. They describe every scene and practically every action, usually in rhyming couplets that feel like watered down Dr Seuss. If Victor looks on in anguish, we’re told about it. I can only assume that Christenson is trying to evoke the feel of storytelling. If he is, then it is deeply ironic because it interferes directly with the natural process of story-telling within a theatre context. The constant telling means there is no tension, no emotional engagement between the characters or audience. It creates a strange sense of stasis so endemic that it actively works against character logic. Not only doesn’t Victor speak up in defence of his nanny, he also stands idly in some other room while his bride is murdered by the monster. One has to wonder not only why Victor is not in the bedchamber on his honeymoon but why he is separated from his love for even a moment when the monster has explicitly threatened to kill her. The monster, for all his murderous ways, is just as bad. He stands by while Victor chokes the monster bride he has been forced to create.

It’s as if Christenson was afraid to deal with the visceral reality implied by the source material. Perhaps this sanitised version is aimed primarily at children. Mind you, most children I know revel in bloody excess. I must also add, as a caveat, that as a playwright I am inherently interested in text. The audience on the night I saw the production seemed enraptured and this was understandable. The design is gorgeous, the performances terrific. The music was forgettable but the singing was strong and committed. This was slick, well-crafted theatre. The setting of an insane asylum made of paper could probably house another story beautifully. It’s just not the house of Frankenstein.

The Vancouver East Cultural Centre, fondly known to locals as the “Cultch”, seems to be an ideal setting for a gothic horror about the possible dangers of playing God. Formerly an abandoned church, its wooden panelling and winding staircase could be creepy if explored alone on a dark stormy night. Tonight the chirpy crowd creates a homely community atmosphere. We cram in, haphazardly thrown together around the least pillar-restricted spots. The uneven floor almost trips me as I make my way round the back of the balcony to the last few empty velvet-covered seats. We huddle together as though round a campfire, eager for the ghost story to start.

Unfortunately the two hour performance doesn’t possess the quirky quality that makes this space so inviting. The eight performers creep hunchbacked and white-faced around the stage, head to toe in the white papier maché-like costuming which also covers the set, oversized beansprout trees and all. They step and grimace in time to the rhyming couplets with which they narrate the story of poor Victor Frankenstein. His childhood, tainted by the death of his parents, and his subsequent unnatural obsession with bringing the dead back to life, resulting in the creation of his monster, are illustrated with frequent songs, clockwork tableaux, and of course, the obligatory lightning flashes. The choppy narrative style keeps us at a distance from the characters portrayed, preventing any lasting emotional engagement. But this gap is not filled with ideas in an attempt at intellectual engagement. The didactic message is clearly spelt out with little space for ambiguity: “if life is a bowl of cherries, one day you’ll choke on a pip”; “the higher you climb, the harder you’ll fall”; don’t mess with nature or pretend to be God, 'cause you’ll get what’s coming to you. The text is strung through with cliché and the irony of the final song of the first act is unbearable: “We’re going to hell in a handbasket; does it get any better than this?”.

After the lengthy courtroom scene that ends the first act, in which Frankenstein’s beloved governess is sentenced to death (we’re not even rewarded with a dramatic execution) for a murder that his own creation, the monster, has committed, my hopes for the second half are not high. However, as the monster – also costumed in white paper from his platform-booted feet to his oversized Stetson – emerges from the shadows to tell his own story, things start to look up. In an unusually touching scene, for once uninterrupted by song and narration, the monster tries to cure his loneliness by befriending an old blind violinist. He breaks down and sobs as he describes his fear of rejection and his companion reaches out to comfort him. Realising that there is something “other” about the creature, the elderly man slowly traces his hands over the gruff monster’s long white claws, and up towards his bandaged face: “Ah, I understand.”

But sadly this friendship, and any potential depth to the piece, is not to be. The man’s family arrive home and chase the creature away in horror; the image of compassion dissolves, along with my tolerance. We are re-introduced to bitty tableaux and songs that fail to elaborate on the rhyming verse. The ideas inherent in Mary Shelley’s novel, her subtle ambiguities about identity, creative responsibility, and our relationship with the outsider, the “other”, seem to have been lost somewhere along the line in this production’s intention to be well-polished. Which it is: well-performed, well-sung, smoothly assembled.

Perhaps the problem here is the show’s packaging. This dummed-down version of Shelley’s novel feels like a show for children, but it isn’t announced as such. I’m bored by the relentless songs, but these might well sustain a 5 year old’s attention through the more complex parts of the plot. I’m disappointed by the lack of darkly gothic frights, but there’s no danger of nightmares for over-imaginative toddlers as a result of a nasty theatrical shock. However, even within the frame of “family theatre”, accompanying parents and older children might still be left wanting something a bit more jagged, a bit more inventive, with a few more original ideas. Nonetheless, the passionate local audience embraced the production…but have they embraced the unknown?

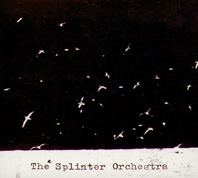

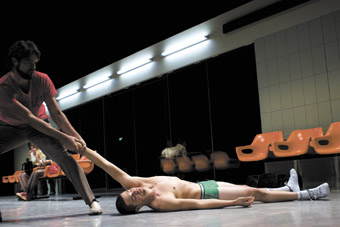

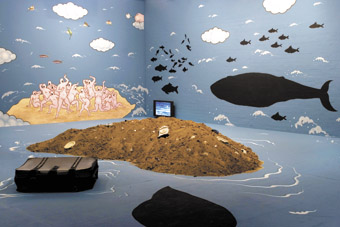

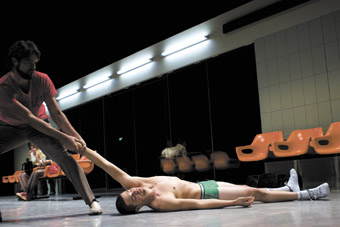

Silvia Costa, Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

photo Peter Manninger

Silvia Costa, Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

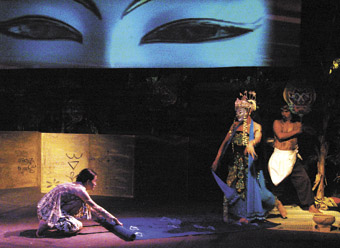

I don’t want to see this. About twenty-five men in street clothes stand together at the back of the stage. A small, blonde, white woman — she could pass as an adolescent — walks toward them. Not long ago they had beaten her. Someone is crying, I don’t know who. It’s coming from behind the men. The woman walks toward them. I don’t want her to go near them, but she does, passing through them untouched. She re-emerges leading another woman, a black woman. But the black woman has the white woman’s head. Her jaw, her eyes, her nose, her short-cropped hair. This head, though, is five times the size. It’s a huge, very life-like replica.

The white woman undresses the black woman, and my anxiety rises. The men leave the stage. All except one white man who, unlike the others, is in 19th century costume, including top hat. He holds out a hand toward the black woman, exhibiting her, offering her. My anxiety increases. The white woman whispers to the black woman, “I’m so sorry.” She then leaves her with the man, who fetches a pile of hay, and leads the black woman to it. He chains her. This, more than anything, is what I don’t want to see. I don’t want to see a female slave auctioned off like a mule on a pile of straw. The man holds out his inverted top hat. The white woman observes the slave woman through four discs—like windows—hanging one behind the other. The windows are streaked and dirty. What image of the slave is the white woman seeing through these glass veils?

Above, the lines from Romeo and Juliet’s balcony scene are projected on a large screen: “How camest thou hither, tell me, and wherefore?…the place death, considering who thou art, if any of my kinsmen find thee here.” “With love’s wings did I o’erperch these walls; For stony limits cannot hold love out.” Where is love in this triangle? And to whom do I attribute the lines? Is the black woman Juliet, the white woman Romeo? Or is the man with top hat either? All of them, none of them? The white woman now digs into her low-rider jeans and produces some coins. She walks to the auctioneer and pays the fee. Is this simple complicity or is she paying for the slave’s freedom? I feel my heart may be breaking. It’s been coming for some time, this sense of grief welling up. Then something shatters. I think I feel a membrane burst in my chest. But it’s the four windows, which all at once have exploded in mid-air, showering the stage with glass.

I’m crying. It’s been coming since the beginning, when the white girl-woman first emerged, chrysalis-like, from the slime of a latex cocoon, when she first crawled like a new-born calf across the strange fluorescent landscape, which is also a soundscape where distant melodies arrive as if through a ventilation shaft. The images from the misty landscape are dense and shifting: a massive broad-sword out of the middle ages next to a bottle of perfume and a tube of lipstick; the girl-woman kneeling, like Joan of Arc, pledging allegiance—but to what? God, king, church, capitalism? Whatever it is, it isn’t hers; it’s an imposition that’s going to use and betray her—as Joan was betrayed. “Dost thou love me? I know thou wilt say ‘Ay’; And I will take thy word.” The girl-woman holds up a sheet, which has just had an ‘x’ burned into it by the giant sword. She stands at the center of that ‘x’, perhaps unconsciously making herself a target.

What’s this about, this heaving in my chest, this performance? I think it’s about one woman’s experience of being a woman. And me, a man sitting in the auditorium? It’s about one man’s imagining of that woman’s experience. It’s about the betrayal of this woman —of women, of innocence, of trust and of love. And it’s about making contact with those things momentarily, making and losing it at the same time. It’s also about sitting in awe at the work of art unfolding before me, at the restless shifting of symbols: first a big bass marching drum, then that drum being held by a naked woman, then the woman weeping over it, then the woman pounding it with the mallets while weeping. Meanings accumulate, line up side by side without cancelling each other out. The black woman is a slave. The black woman is painted silver by the white woman and given a sword. The silver-painted, armoured black woman puts on high heels. What is feminine, what is masculine, what is submission, what is rebellion? Hey Girl! doesn’t collapse these things to a single point. It enfolds meanings then distributes them liberally. There is plenty of room in this world for my personal ache and wonder.

Hey Girl! gets a hold of me and doesn’t let go for 75 minutes. It ended at 8:45 last night. It’s now almost noon and I’ve barely slept. I keep turning the images over in my head, the ones I drank in and the ones I couldn’t look away from. Director Romeo Castellucci, his designers, and the two women, Silvia Costa and Sonia Beltran Napoles, did that rare thing: they dislodged my thinking, allowing the images to bypass my mind and go directly to my body. They fed me, and they made me see what I didn’t want to see. “Therefore pardon me, And not impute this yielding to light love, Which the dark night hath so discovered.”

Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio, Hey Girl!, director, design, lights, costumes Romeo Castellucci, performers Silvia Costa, Sonia Beltran Napoles, original music Scott Gibbons, statics and dynamics Stephan Duve, lighting technique Giacomo Gorini, Luciano Trebbi, sculptures Plastikart, Istvan Zimmerman; Frederic Wood Theatre, University of British Columbia, Jan 23-26; PuSh International Festival of Performing Arts, Jan 16-Feb 3

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 8

© Alex Ferguson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dov Mickelson, Tim Machin, Sarah Machin-Gale, Nancy McAlear, Frankenstein

photo Photomagic

Dov Mickelson, Tim Machin, Sarah Machin-Gale, Nancy McAlear, Frankenstein

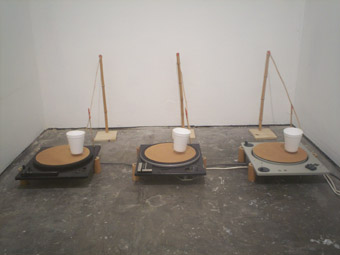

A blind old fiddle player and the Creature (aka the Frankenstein monster) talk around a campfire. The Creature (George Szilagyi) is attired in what looks like shredded, white, hand-made paper. So is the old man (Dov Mickleson). Softer white fabrics are also layered into their costumes, and the paper covers almost every set piece, including the two stumps they are sitting on (designer Bretta Gerecke). White grease-paint completes the wintry, deathly tone of the setting.

When you take in a Catalyst production, you get a world that is aesthetically complete. You can expect rigorous consistency of appearance in the design, and persistence of tone in the performances. Which makes the scene described above a bit of an anomaly. In what is a rare exception to the rhyming couplets that have dominated the script, we are given prose dialogue. The scene is also unique in allowing two characters a stretch of uninterrupted conversation. Normally, ever-present narrators comment on the action. The Creature pleads for understanding (“Please don’t hate me”), and the old man offers his compassion. The scene is affecting in a way that the play’s alienating performance style hasn’t been, up to this point.

Virtually the entire play is delivered in metered verse, spoken or sung by a group of gothic spectres who seem to have emerged from an icy northern crypt. They lurk, they twitch, they glide. There’s a bit of the B-movie hunchback in some of them, others opt for the menace of Boris Karloff or Vincent Price. Judging from the corny, aphoristic content of much of the script, these references are probably deliberate. In fact, the text offers an almost exhaustive supply of proverbs and platitudes: “The higher you climb, the harder it is when you fall.” It’s relentless and uncompromising in its devotion to end rhymes — Which is easy enough to do / Whether you’re happy or you’re blue / Writing great dramatic text / Or just a snarky little review.

The narrative is handled in an equally simplistic manner. We are given a generic psychological sketch of Victor Frankenstein’s journey from happy child to tormented scientist: childhood trauma is the source of adult obsession. This biography is faithful to the broad outlines of Mary Shelley’s novel, but it’s short on the kind of details that offer genuine insight or build a character portrait that is unique or surprising. Despite the two-hour duration of the show, character relationships are likewise merely schematic and therefore unaffecting. Instead of narrative layers, we get a strong design concept, and highly competent physical and vocal work by the actors. Don’t get me wrong, I love image-based theatre, physical theatre and contemporary dance — I can easily do without psychological character development. But in the case of Frankenstein, form and style fail to make up for a lack of nuanced story telling and complex character relationships.

What seems to be missing from the outset is a genuine question, a speculative point of departure. Writer-director Jonathan Christenson has made up his mind about the issue, the meaning is prescribed: too much tinkering with the laws of nature is a bad thing. This lack of ambiguity is evident in Victor’s relationship to the Creature. He despises him and doesn’t waver from that position until the very end. Until that point he suffers no inner turmoil about whether he should terminate his scientific progeny, so there’s no issue to wrestle with. As a result, there’s really no play here.

Maybe it’s a control issue. As writer, director and composer, Christenson seems to have kept a tight leash on every aspect of his creation. Unlike the creature in Mary Shelley’s novel, Christenson’s monster — the production — lacks the capability to rebel. It’s ironic that a play about a scientist-inventor is lacking in invention. The show plods along methodically, like a rhyming pattern that won’t quit, like a thesis question that presupposes its answer.

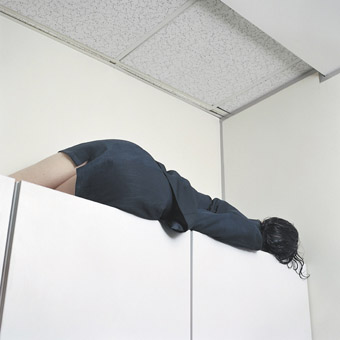

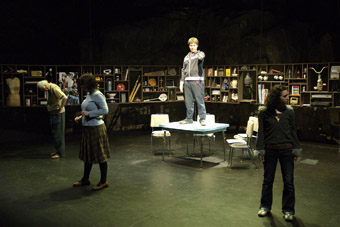

David Carberry, Darcy Grant, The Space Between

photo John Donegan

David Carberry, Darcy Grant, The Space Between

In thinking of circus performers—particularly acrobats—the first emotion one feels is the thrill of sensing the danger that the performers may fall. The second, and perhaps surprising, emotion is a sense of comfort at seeing how the performers support one another. The overriding bond between two acrobats who rely on each other for their physical well-being must be one of trust. Comfort is derived from witnessing that trust affirmed. We see how powerful—and life-protecting—trust can be and this becomes the implied message of all circus performances. The language of physical theatre therefore comprises two inter-related elements or apparent polarities, risk and trust, repeated throughout a performance. This is manifest also in the individual performer: trust that their body will support them and save them from the harm of risk.

For most of us, trust in is one of the hardest things to achieve because of the inherent risk of putting our faith in others or, indeed, ourselves. Will we be let down, disappointed, left to fall? I suspect trust is a key theme in The Space Between but I’m not sure. Movement is not a language in which I’m particularly fluent but I trust the performers and creators to explore the themes fully.

There is no obvious narrative driving The Space Between. Instead we have three performers—two males, one female—working alone or in pairs with the occasional scene featuring all three. The links between scenes are more impressionistic than direct, building a layered exploration of the relationships between the performers. Like a poem, perhaps the key is in the title.

What is not in doubt is the sheer physical prowess of the performers. The show opens with a single performer falling backwards. He falls repeatedly before tumbling back onto his feet. It has a form of gracefulness but it is the sheer athletic skill, the physical energy and ability that strikes one. This visceral physicality is on display throughout the show. There are sequences where the performers tumble, roll and crawl across each other’s bodies. These are balanced with moments of stillness where the performers hold each other at dramatic angles. In a memorable sequence the female performer holds a small scarf while one of the men dives over and under it like a land-based dolphin. Amongst the solos, there is a wonderfully executed sight-gag involving a performer one of whose hands sticks to any surface it touches. The comic logic of the gag is followed through beautifully as his hand attaches to various parts of his body and the floor and he must contort his body accordingly. In the same scene the performer manages to get a collective wince out of the audience as he twists around on one wrist and seems to have dislocated his shoulder.

The playing space is simple—as it should be—a grey square with the audience on three sides. An occasional projection appears directly on the floor. These are always square and include letters or geometric shapes. The performers move through them but the effect only really lifts off when the square of light rotates and the male performers look like they’re flying on a magic carpet. The music is an eclectic grab bag ranging from electronica through to Serge Gainsborough and Neil Young. Sometimes it works well, sometimes it’s a little too obvious and other times it’s just there.

The Space Between builds to a trapeze scene involving a repetition of the physical gestures we’ve seen played out on the floor but with the extra sense of risk engendered from being suspended. There are a couple of breathtaking moments when the female performer is about to fall only to have the male performer deftly capture her—or at least seem to. Towards the end of the same scene there is a moment where he appears to hold her using only his hand in her mouth. It’s a brief but striking image that seems extreme when compared with what has gone before. There are allusions to male threat, for example when the men grab hold of the woman and swing her back and forth like a skipping rope but there was no sense of overt menace. While we see the potential for physical danger, we fully trust that the male performers would not allow any harm.

Although the moments on the trapeze involved risk, I’m not sure that they evoked vulnerability, and that’s what I thought was missing. I can’t escape the sense that the basic, physical language of circus—built on the polarity of risk and trust—makes it difficult to achieve more emotional nuance. While there were some tender moments—particularly between the two men—I can recall only one of overt aggression, again between the males. It is surprising in a piece about a love triangle that anger does not appear more frequently. Of course, as one male flew at the other in rage we could see the second male brace himself as he prepared his body to actually support his colleague. It was comforting to see.

Henri Chassé, Annick Bergeron, Août – un repas à la campagne

photo Rolline Laporte

Henri Chassé, Annick Bergeron, Août – un repas à la campagne

A meal in the country; what a lovely idea. We could sit on this long narrow porch by the maple trees, and drink lemonade while Grandma gathers fresh eggs for an omelette. If only it weren’t so beastly hot. Heat always brings out the worst in people.

Monique (Marie Tifo) and André (Jacques L’Heureux) are fifty-something city dwellers who just got engaged, and have come out to the country for a pleasant celebration on Monique’s brother’s farm. The marriage is imminent and clearly doomed. “He likes women who wear bracelets,” Monique says of her fiancé. “And then he gave me some.” She thrashes her arms with their cheap bangles. André is an emotional lightweight, who says golf “helped me grow as a human being.” But somehow the presence of this outsider adds the extra pressure that will crack the entire family by curtain, just 70 minutes away.

We know it’s a tragedy from the start only because that’s how it’s billed, and the dramatic tension in what appears to be a comedy comes from trying to guess the family secrets, whom the tragedy will strike, and what the agent of disaster will be. The play is shot through with false dangers: an escaped snake, the rusty chains of the porch swing, a heart condition in a heatwave. Even the acid rain that’s destroying the maple syrup crop sounds like it has potential to turn the plot. “A mystery is a mystery until it isn’t a mystery any more,” Monique says. “And then? I love that feeling.” The playwright guides the audience towards the feeling Monique loves. As it turns out, the real danger comes from the people to whom we are closest. We can’t always see it because our eyes can’t focus in that proximity.

Jean Marc Dalpé’s Août: un repas à la campagne is a realistic play in a naturalistic setting that takes place almost entirely in real time. A classic drama, Août demands strong ensemble acting, and depends entirely on the text to work. This ensemble delivers, with no one actor dominating the stage, and no one character pitched too high or too low. The actors never seem to be acting; they’re just normal people doing and saying regular things. Fernand Rainville’s direction moves the eight characters naturally on the long narrow stage, and a family we’ve never met before starts to look very familiar. Design elements are deliberately spare. Crickets chirp. The lights change twice. The effect of this restraint is powerful.

In describing Dalpé’s writing, the program notes use the concept of ‘justesse” (roughly: the accuracy that allows authenticity). Everything is purposeful, and everything contributes to the final effect, which happens entirely without words. It’s no mistake that people keep blocking each other in the driveway, or that they keep asking for keys and are often denied. That doesn’t mean the audience always knows the purpose of each moment, although the playwright clearly does. About halfway through, Gabriel (Henri Chassé) is absolutely thrilled when he captures a long garter snake. It later escapes. Gabriel’s role in the play’s climax makes it appropriate for him to be associated with a phallic symbol, but the play is so well crafted that this long scene must have additional significance. The author plays with this gap in meaning, as the characters ask themselves what it means to catch a snake – does it represent good luck? No one is sure. Like us, the characters have lost touch with ancient symbols as the maple trees die, the golf course moves in, and they move out to the city with dreams of screenwriting glory.

The snake is seven feet long, and after the tragedy strikes, the Grandmother (Janine Sutto) returns to the stage triumphant, with seven eggs she has found. These symbols – the number seven, the snake, eggs, keys, barred passages, and the final image of a mother who should protect but instead takes on the role of avenging god – crawled over my brain like a vague ancestral memory. I knew the meanings once, maybe from hundreds of years back when every meal was a meal in the country. The play would have had an even greater effect if I could have accessed those memories in the moment of watching, but it’s also enjoyable to work away at the mystery long after the actors have gone home. Août is a rare achievement – a play that lingers and sticks, like a long, hot summer day.

Incidentally, the play, created by A Théatre de la Manufacture from Montreal in association with Vancouver’s Théatre la Seizième, is presented in its original French. English surtitles were projected above the playing area. The experience was rather like watching a three-dimensional movie with one eye shut. To really savour this text the way it deserves, nothing but full fluency would do.

Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

Raffaelli

Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

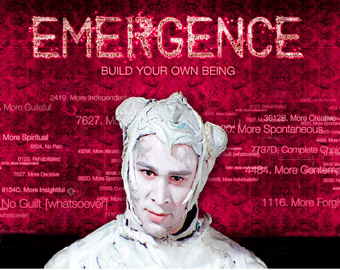

About three-quarters of the way into Hey Girl, the unnamed “everygirl” reappears on stage wearing an oversized head mask. It’s creepy. Not only is the mask extraordinarily lifelike, it focuses attention on the woman’s body in a way that turns her into a grotesque overgrown child. The head ends up on the stage next to a giant sword as if hacked off by an unseen executioner. A few moments later a second woman appears with an even bigger mask of the same head. This second head is neatly deposited next to the first. Initially, I thought the masks were meant to represent Princess Diana and my first reaction was “Hoo boy!” I found out later that I was mistaken. The heads were in fact enlarged versions of Everygirl’s own.

For better or worse, the connection to Princess Diana is made in and I can’t shake it. I find myself wondering how Romeo Castellucci felt on hearing the news of Diana’s death? Was he distressed? Did he rage against the paparazzi, those dreadful men who hunted down and killed this “beautiful woman”? At one point in the show, Everygirl kneels next to the sword and lists the women – Anne Boleyn, Marie Antoinette, Katherine II of Russia – who “lost their heads on account of the people”. I don’t think Diana made the list but it is certainly company she would feel at home in. My sense is that – at core – Everygirl doesn’t represent all women but rather those beautiful women objectified by men only to be destroyed by them. It has to be noted that Everygirl is stunningly beautiful. She’s also fit. And blonde.

Rather revealingly, the central performer’s name is missing from the PuSh program guide [and there is no print program at the venue]. I don’t know whether this is an administrative error but would not be surprised if it was a conscious choice. Objectification is a central theme of the work. In an early scene, Everygirl moves slowly to the back of the stage and stands on a pedestal. She’s naked but her features are blurred through the haze of smoke that clouds the theatre. She reminded me very much of those small, wooden dolls that artists use to strike different poses – she is strangely inhuman. She then moves downstage and beats a drum with violent force and emotion as if – perhaps – to signify both her emotional energy and individuality. She dresses in jeans and a white t-shirt. I liked this touch as it made the performer both human and very contemporary in what is an extremely abstract environment. We could recognize her, although not so much as the girl next door as Kate Moss dossing around the house on a Sunday afternoon.

In the necessary short-hand our society is addicted to, Romeo Castellucci is described as Europe’s answer to Robert Lepage, the theatre auteur from Quebec. In the usual way of these things, it’s a misleading description. Lepage is an inherent performer and storyteller; both roles are woven into the very fibre of his work. Castellucci, on the other hand, is a designer who borrows heavily from the visual arts field. Lepage uses innovate design and stagecraft, these tend to be pure and simplified and used to support both narrative and theme. Lepage uses simplicity to convey complexity. Castellucci – at least with Hey Girl – uses visual and auditory complexity to reveal…not much, really.

That said, Hey Girl is one of the most visually stunning and technically brilliant shows I’ve ever seen. It is also one of the most didactic and condescending. I longed for depth but I fear there is none. When Everygirl points accusingly at the audience, I think it’s sincere. But I wonder if the brutal treatment of women in Western culture was news to many members of the audience? There is also a rather disturbing psychology underlying this work which links back to the notion of objectification. There is a scene where approximately 30 men invade the stage. The smoke in the theatre casts them in shadow and – while three of their brethren watch through a glass window – they beat the woman with what look like pillows or sacks. The image is heavily stylized but still distressing. After the beating the men line up and in flashes of light we are able to make out their features. They are us! Men drawn from the street! I couldn’t help but reminded of certain Hollywood films which show women being beaten and raped because we need to know just how brutal men can be. It wasn’t nearly that extreme but I do wonder at reproducing the pathology that objectifies a woman and then beats her. I realise this is the point but I don’t feel Castellucci earned this moment nor do I believe that the thin thematic content justified it. The simple code of the piece is: beautiful girl is alone, confused and abandoned, an object of desire she’s beaten by men only to rise again ready to kick ass, Buffy-like sword at the ready.

But wait there’s more! There’s a scene where L and R appear on opposing sides of the stage. These large letters light up – with a deafening racket – while Everygirl races between them as if pulled to and fro! Later, Slavegirl (a gorgeous, of course, black woman) appears and Everygirl buys her from a slave trader! Everygirl pleads “what must I say, what must I do”! This is a world where women are not capable of being agents of change. It is a world where women are isolated and victimized (until they discover sisterhood, as defined by Castellucci). This is the thin gruel we are left to digest.

But why would I encourage you to see it? Because it is visually (and to a lesser extent aurally) stunning: in particular, the opening sequence where Everygirl is lying on what looks like a coroner’s table, covered in dripping latex paint which has formed a skin over her body. It is beautiful, haunting and unforgettable. There’s a clip from this scene on the internet. See for yourself how beautiful the performer is. Maybe you can even discover her name.

Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

photo Raffaelli

Hey Girl!, Socìetas Raffaelo Sanzio

The space is pitch black. A fluorescent strip light upstage sporadically flashes on and off. Silhouetted against these violent interruptions, a young woman’s body is stretched out on the floor, uncomfortably twitching and writhing. She seems to be suffering some kind of fit, or is she forced to dance involuntarily by an unseen power? Unsettling, inhuman electronic noises cut through the dark, slicing into our consciousness: monster-like groans and unfamiliar clicks.

A longer flash, and the silhouettes of three male figures appear. Their backs to us, they group downstage and stare up at the woman. Their silent invasion is threatening and unnatural. Another flash. A male figure dashes into her space, close to her this time. The next flicker. He beats her with a square panel, maybe a cushion, maybe something harder than that. The other men look on. The repetitive thwacking of the attack continues even in the dark. In the next glare we see a couple more men hitting the girl. A second later there are five or six men grouped round her cowering body, beating her repeatedly. A split-second, and there are double this number of men. The onlookers have now joined the abusers. The noise crescendoes. A flash; more men. The new additions can’t reach her body so they beat the floor, the density of the thumping emphasising the sheer multitude of this gang. The flashes accelerate. Red flashes alternate with white. Each time the light blinks more men appear, swarming around the woman until it’s impossible to count. An overpowering slideshow. I am afraid what I will see in the next disorientating flicker.

This time the light stays on for a couple of seconds. The men are frozen, their backs to us, their weapons lowered. The woman is no longer visible. Light off. After the physical assault on our senses, this calm is more perturbing in its unpredictability. Light on. The men are lined in a clump upstage facing out to the audience. Their bodies are now lit, but despite their everyday clothing they still retain the faceless intimidating presence of the silhouetted gang. The girl, curled in a ball, slowly lifts her head. As in an alarming Alice in Wonderland nightmare, her head is now overgrown, disproportionately big on her tiny body, as though she should topple over under the weight of it. For a second I can’t make sense of this image. The uncannily life-like mask tricks me. I start to feel the dizzy lurch of travel sickness.

I have no idea how long I have been submerged in Castellucci’s vision. From the moment that the lights went down on the smoke-filled auditorium and we witnessed the birth of this wispy young blonde, emerging alien-like from a cocoon of dripping plastic gelatine, my faculties have been cut off from anything other than this terrifying world. Beautifully disturbing images have invaded me, touching obscure parts of my consciousness left dormant until now. I have no idea what to do with these pictures, and although the pace seems dream-like and slow, there’s not enough time to process one surreal image before the next appears. Picturebook words – “cat”, “horse”, “train” –are projected onto a screen as the light slowly rises and fades. The girl cries “please shut out the light”. We read the text of an intimate scene between Romeo and Juliet as the girl helps to remove another, larger version of her own head from that of a naked black woman. As we read new meanings into these words, the snatches of seemingly unrelated information link into one movement. It seems best to let this flood through you, rather than wash over.

Images that in themselves may be unsubtle or too literal seem to gain integrity and mystery in the context of this structure and through the clarity of the visual presentation. The black woman, still naked, is shackled by a bearded white man in Victorian top-hat and coat. The blonde woman buys her freedom, then points at the audience. This is not the first time that this gesture has implicated the audience in a crime committed in front of us. Whether she is apportioning blame or calling for action is left to our consciences.

We see this newborn creature boldly spurn contemporary femininity as she pours a bottle of perfume over a burning sword, angrily creating a shrine to the “queens who lost their heads on account of the people”. She is wise but she is also attempting to learn the rules of this place she is trapped in, just as we try to make meaning of what we see. Although she is strong she is not ultimately in control of her surroundings and her confusion and pain become a vivid metaphor for our experience of Hey Girl!, and for our own struggle to learn to live.

A painfully bright red and blue laser beam suddenly shoots down onto the girl’s face, burning our retinas, as a continuous high-pitched screech cuts into our ear-drums. The woman next to me puts her fingers in her ears. Many words are rapidly projected onto a screen, almost too fast to read this time. They halt occasionally: “porn”, “menstruation”, “mammiferous”. This seems to be a mechanical transfer of knowledge from machine to organic organism, a science fiction education on the adult aspects of this haunting world. The process is distressing, a physical violation of this small, thin being.

However, unlike this intervention, the process of Hey Girl! is bewitching because it refuses to guide our thoughts or spell out meaning. Each audience member re-enters their own solid world as they leave the auditorium, and perhaps we walk away with similar thoughts about femininity, sacrifice, servitude, empowerment. But the more intricate and unique imaginings that have been triggered in the last hour just might lead to further discovery within minds that believe they have already learned themselves and their world.

It’s only a seven-foot garter snake in a bag, caught because it was busy eating a toad. But it causes a commotion: the glamorous Monique dashes into the house and won’t come out; her brother cruelly forces her fiancé to bond with the men by measuring the beast; and old, ornery Paulette falls half in love with the thing when she puts her finger in the bag and feels its tongue lick her “like a caress.”

Henri Chassé, Annick Bergeron, Août – un repas à la campagne

photo Rolline Laporte

Henri Chassé, Annick Bergeron, Août – un repas à la campagne

It’s only a family gathering for a few days in August to prepare for the wedding of Monique (Marie Tifo) and André (Jacques L’Heureux), the second marriage for both. Août – un repas a la campagne takes place on a simple set: the front porch and window-view-only two front rooms of a wooden house in rural Quebec (as the dialogue gradually reveals). This particular afternoon is hot enough to melt reason. As Jean Marc Dalpé’s play progresses, it’s clear that reason – and humour – had been the short fences keeping chaos out of the yard. When these small protections fail, the family can no longer deny that Monique’s niece Louise (Annick Bergeron) has been cheating on Gabriel (Henri Chassé) without taking much care to dissemble. Facing that releases shame, desparation and pain for all of them.

Dalpé, who also acts the part of Simon, emulates Chekhov in several ways. The discussion about whether or not maple sugar trees are a dead-end investment or a chance to strike gold on the Japanese market is, of course, a nod to The Cherry Orchard. Dalpé’s use of casual, chatty conversations to build slowly to explosive moments reminds me of The Seagull, especially the way dialogues bewteen characters overlap. For example, Louise and her mother Jeanne (Sophie Clément) talk distractedly about whether to use a yellow or white tablecloth for the outdoor meal; between comments, Paulette (Jeanne’s mother, played with stiff, curmudgeonly humour by Janine Sutto) insists she would rather have an omelette than pork roast for dinner.

Also, as in Chekhov, these are ordinary people wearing regular clothes and having conversations about nothing particularly pressing. Until, that is, a conversation pushes a character to an emotional peak. Monique and Joseé (Catherine De Léan) – the funny, constantly distracted, lone representative of the youngest generation – have a rambling chat about looking endlessly for something that isn’t where it should be. The exchange is hilarious but also sets the tone for the kind of helplessness several of the characters experience as events unfold. André discusses golf as the healing pathway out of grief for his late wife. Gabriel only talks about home repairs, beer, swimming, the snake, until Louise provokes him by announcing she will go stay with her lover for three days to think about things. In response, he angrily, methodically describes what he’s done on the farm, which he only has rights to through the now-failing marriage, shouting (I paraphrase the translation) “I’m not leaving without getting paid back for those twenty-one years!” The dark undertones of the cagey, carefully lighthearted behaviour in the previous scenes become visible, and this ripple of of understanding backwards through the play yields a sense of empathy.

A three-time Governor General’s Award winner, Dalpé has a strong enough aesthetic to fold Chekhov into his play without being derivative. In the context of the PuSh Festival, which is dedicated to contemporary performance and is willing to take risks with experimental work, it’s interesting to note that August is neither a fusion of forms nor and attempt to invent new theatrical styles. Director Fernand Rainville is thoroughly experienced in shaping award-winning productions and has been a longtime associate with Théâtre de la Manufacture (Montréal), causing national excitement with Howie Le Rookie in 2007 (Théâtre la Seizième, Août’s co-presenters, brought Howie to PuSh that year as well). The actors are popular stage and television players in Quebec; the production at Waterfront Theatre was expert, down to the easily readable surtitles that provide access to anglophones like myself.

Août – un repas a la campagne expands the range of PuSh by including an experience of Canada’s other major language, which is not always easy to find in British Columbia. When traditional theatre is this well done, it can, and does, dig deeply into our psyches – just from a different direction than the bearing experimental performances use. Rather than grabbing us by the ears and throwing us into a world of devilish cabaret, for example, Août sidles up and shows us a snake in a bag that may kiss us or curse us. For me, Août’s eight characters were so well-rounded that, the night after the show, I dreamed about three of them as people in other contexts (Monique, André and Louise stranded by a pickup truck on a dusty road). Transformation can come to us subtly.

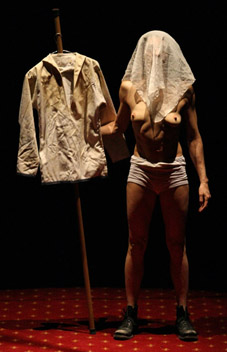

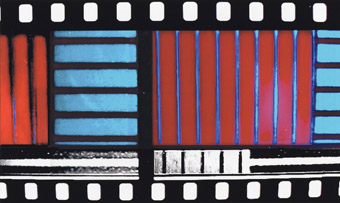

The Black Rider

photo Ian Jackson

The Black Rider

There is an old vaudeville theatre in Vancouver’s notorious downtown eastside. It’s been closed for years. For some reason, The Black Rider put me in mind of the crumbling glory of the Pantages. With its expressionistic tone and sense of rotting decay, November Theatre’s production would be more at home there than in the utilitarian blandness of the Granville Island Stage.

However, it’s not vaudeville but the carnival that is evoked at the top of the show as Old Uncle (Mackenzie Gray) invites us – in the fashion of a sideshow barker – to join the Black Rider. While assuring us of a “gay old time”, he lists the freaks that will be on display for our pleasure. Any fear that we are about to experience a bewildering series of unrelated vignettes is soon dispelled as we are caught up in the story of young couple: Wilhelm (Kevin Corey) and Kathchen (Rachel Johnston). The girl’s father, Bertram (Jon Baggaley) forbids their union because Wilhelm, a soft city clerk, is not a hunter, an occupation integral to the history of Bertram’s family.

To win Kathchen and impress Bertram, Wilhelm makes a deal with the devil-like Peg Leg (Michael Scholar Jr), who offers him magic bullets that are guaranteed to never miss their mark, no matter what direction Wilhelm shoots. He quickly bags enough game to impress Bertram but, of course, any deal involving the devil is bound to sour and ultimately Wilhelm loses the object of his desires by his own hand. Taken from a German folk tale, this narrative provides the simple but durable structure to house the songs and music of Tom Waits and the heightened, poetical language of William S Burroughs.

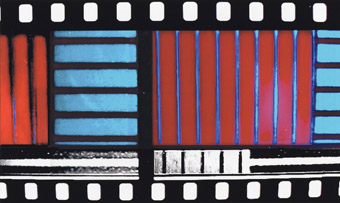

No doubt reflecting its production history – The Black Rider was originally mounted as a fringe show – the piece is spare with a firm emphasis on performance and music. A small band of three musicians – playing a variety of instruments – are holed up on one side of an otherwise empty playing space. Thick vertical stripes of deep reds and blues form an effective backdrop upon which images of rifles and trees are projected. To create a carnival-like atmosphere with such a stripped down aesthetic requires ingenious stagecraft. There are some wonderful moments, for example when Wilhelm hides under Katchen’s wedding dress and uses his hands to create grotesque, rather dextrous feet for his bride-to-be. Other moments – a flapping kite for a bird – are less effective.

The six actors are fully committed to an expressionistic approach that includes white face, highly stylized movement, clowning and heightened vocalizations. With the aid of just a few props, they successfully create a hallucinatory, drug-like world. Such a performance style naturally has an alienating quality to it that shuts an audience out from emotional engagement with the characters. While this reinforces the flatness of the folk tale narrative, it can make the work difficult to take for stretches and I did find myself longing for pauses from the shrieking and clockwork movements.

Still, without losing any commitment to the expressionistic aesthetic there are some surprisingly touching moments, particularly between Wilhelm and Kathchen when they sing their duet, The Briar and the Rose. In the end, Corey’s Wilhelm provides the spine of the piece. With his deft use of physical humour, Corey reminded me of Chaplin with the same sense of a clown lost in a bewildering world. Johnston provides a strong, physical counterpoint to Corey. She is striking in both red dress and wedding gown, creating the weird doll-like creature of his desire.

Playing the devil, Scholar is allowed a little more freedom in his movements. There is a sultriness to his character, a physical prowess that the limp of his peg-leg surprisingly accentuates. The character, and Scholar’s performance, reminded me of the MC from Cabaret. Peg Leg isn’t the host of the evening – although he does close the night cabaret-style. Instead Old Uncle acts as our guide for most of the night. While Gray gives a powerful performance, I was less sure of the choice to mimic Tom Waits’ distinctive, husky singing voice. I found this affectation rather distracting, taking me out of the world of the piece.

The story of the magic bullets is meant to evoke the dark other-world of addiction. Ironically the stage is often flooded with light – perhaps to evoke the footlights of the 19th century. Instead of a rundown theatre, the flat, bright lighting put me in mind rather of a school auditorium. But then so does the Granville Island Theatre generally. I longed for more darkness, more shadows, more decay. I wanted to be closer to the performers somehow, pushed right up against the stage.

There is a dedicated group in Vancouver trying to save the Pantages Theatre. If they succeed, I hope they will consider this show for the re-opened venue. The Pantages languishes in a dark, decaying part of our city; a place where the Black Rider would feel at home.

Patti Allan (appearing with the permission of the CAEA) & Spencer Atkinson, Old Goriot

photo Tim Matheson

Patti Allan (appearing with the permission of the CAEA) & Spencer Atkinson, Old Goriot

Don’t get excited. Stay calm. Watch. Listen. This seems to be director James Fagan Tait’s advice to the spectator in his production of Old Goriot — restrain yourself. His adaptation of Balzac’s 1835 novel is starkly placed in the dark expanse of the Telus Studio Theatre. Just a few essential set elements and a large cast decked out in period dress evoke Balzac’s Paris, while the dialogue, transposed to recent North American vernacular keeps us anchored in the present. A large scrim forms the back of the playing space, variously taking on a sombre palette of projections, which include baroque wall paper, an opera house, and a Parisian boulevard. To one side, a three-piece chamber orchestra of marimba, double-bass, and bass clarinet remains quietly present. A massive dining table drives forward from the scrim. The action of the play takes place on or around this stage-within-the-stage.

In the opening scene, about fifteen actors, inhabitants of Madame Vaquer’s lower middle-class boarding house, line three sides of this table, spooning and slurping their soup in unison, heads falling and rising mechanically. Individual heads then swivel one by one toward the audience as each character makes an introduction. But you’ve got to listen carefully, don’t rustle in your seat — these actors are deliberately keeping the volume down, forcing you to lean forward to catch every word.

What unfolds, in this hushed manner, is the story of Rastignac (Spencer Atkinson), a social climber seeking to marry any moneyed socialite who will have him. Despite the most calculating advice offered by his upper class cousin, the Comtesse de l’Ambermesnil (Anna Hagan), and criminal but advantageous arrangements made under the corrupting influence of the worldly Vautrin (David Mackay), Rastignac keeps getting tripped up by his romantic desire for true love. His affections end up falling on one of the daughters of Old Goriot (Richard Newman), a sombre and mysterious geriatric who also lives in the boarding house despite the fact that his daughters are fashionable ladies of Paris society. Rastignac will learn harsh lessons as he witnesses the daughters’ unfeeling betrayal of their father’s blind devotion. At one point Rastignac and Delphine (one of Goriot’s daughters, played by Cecile Roslin) argue across the body of the dying old man, she wanting to hurry off to the ball, he complaining, “I can hear your father’s death rattles.”

Despite this melodramatic sounding plot, almost every actor tenaciously underplays his or her part. No emotional ostentation — just simplicity of movement and an almost filmic vocal delivery. Director Tait establishes a tone of dispassionate observation and sticks to it. Even the musical numbers, composed by his longtime collaborator, Joelysa Pankanea, and hauntingly performed by her trio and the actors, are spare and contained. It’s Brechtian — that is if Brecht were to produce a period piece and perform it in slow motion. Old Goriot is full of Balzac’s shrewd analysis of the grim reality of France’s brutally stratified society, and Tait keeps us in an observer’s frame of mind by refusing to build dramatic momentum, and undercutting sentimental identification with characters that remain composed, slightly casual, offering only reference to anguish rather than fully embodying it.

Tait’s been working this aesthetic since Crime and Punishment, his 2005 adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s novel, which was a landmark production in modern Vancouver theatre history. One of the defining features of that production was the inclusion of five actors from the downtown eastside, a neighbourhood that has the dubious claim of being Canada’s poorest postal code. Of that production, Vancouver director/dramaturge D.D. Kugler remarked that watching the twenty-five member cast was like seeing a cross-section of the city on stage, something he’d never experienced before. Goriot is a mirror of that show, the main differences lie in the absence of the downtown eastside actors and the much more cynical bent of this play. Where Dostoyevsky’s novel builds to a spiritual crescendo, Balzac, through Tait’s filter, stays firmly planted on the unrelenting ground of modern class warfare.

In the case of Old Goriot, based on a novel some consider the father of the realist movement in literature, Tait’s approach serves the realist’s mission of looking at life ‘objectively’. He certainly strips Old Goriot’s death scene, masterfully played by Newman, of any sentimentality. Realizing his beloved daughters won’t be joining him for his final moments, the old man meanders between curses and expressions of undying love, as he tries to come to terms with the lonely predicament of his demise: “They’re not coming. I’m going to die like a dog.” His monologue is both interminable and engaging — I felt like I was watching the death of giant insect that had suddenly become aware of its own mortality: I was curious, mildly disturbed, and feeling just enough of an ache to raise a flicker of empathy. This scene was the highlight of the production for me. But a kind of low highlight. After all, Tait wouldn’t want us getting carried away by grief or laughter. Just stay calm. Listen. Assess.

Michael Scholar Jnr, Kevin Corey, The Black Rider

photo Ian Jackson

Michael Scholar Jnr, Kevin Corey, The Black Rider

The stage for Black Rider is dressed only with three columns of red light on a blue background, like a triple projection of Barnet Newman’s painting Voice of Fire. But the Black Rider quotes more than modern art. It’s based on a German fable of the Middle Ages; it also reeks of the popcorn smell of the American big top and the stale grease makeup of clowns. It quotes Byron and T. S. Eliot. It has Broadway melodies and Latin rhythms. In some moments, it’s positively Gilbert and Sullivan, as envisioned by people who don’t like Gilbert and Sullivan. And in this production it’s held together by the visual continuity of actors in exaggerated makeup who can move gracefully when required, but tend more to contorted bodies and faces, and to any gesture but real.

The style of movement varies almost at random from the pointed toes and sweeping limbs of ballet to the tumbling of the circus, and exaggeratedly bent arms and twisted torsos that come from some less familiar tradition. Speech varies as dramatically. Actors sing naturally while holding crooked poses, or distort their voices past intelligibility. The text morphs from moralizing to hucksterism, exposition to character. It’s oddly alien and familiar at the same time, without necessarily creating a strong, overall effect.

In this November Theatre version of the Waits-Burroughs-Wilson original, German expressionism goes to the circus, but it’s a cheap circus playing a small town, and the performers are giving it their all. They’re talented as hell, but their aping faces and distorted limbs distract them and their cheerful audience from the fact that this is, at one level, a story about drug addiction. As some will know, Black Rider’s writer, William S. Burroughs, was a heroin addict who accidentally killed his wife in a shooting game. In this production, when Wilhelm, the inept suitor, accidentally shoots his bride on their wedding day, with a bullet he got from the Devil to give him a marksman’s skill, few will guess at the resonance. The absurd, self-mocking gestures of the actors sometimes do work to hint at the self-loathing that must accompany addiction and homicide. In one of the final scenes, the morose Wilhelm ties himself up in a straitjacket made of his own dress coat, telling us that making deals with the Devil is the province of the insane. A moment of pity allows a brief connection.

Addiction can get ugly, and this production is most successful when it’s ugly and in the rare moments of sincere emotion which punctuate a lot of intentional silliness. Kathchen (Rachael Johnston), the bride-to-be, gets to scream twice: full-bodied, deliciously ugly screams that you rarely hear on stage or anywhere else, and in this case, electronically augmented to strong effect. Sincerity appears by surprise in a production that otherwise cultivates the absurd. The doomed lovers are truly touching only once, when Wilhelm plays with Kathchen’s toes as they sing the Briar and the Rose. It’s a straightforward duet in a production that would rather discomfit and jar the audience. Wonderful inconsistencies also appear, as in a love song that mixes predictably romantic words with phrases like “I’d be the pennies on your eyes.” Death and matrimony rarely converge so playfully. Too frequently though, it’s hard to find a connection and maintain it. I spent a good chunk of the lingering death scene wondering at the strength of Johnston’s legs as she inched herself to the floor.

Is there a point in reviving German expressionism after its era has passed? Without the rancorous signing of the Treaty of Versailles after World War I, without the cabaret nightlife of Weimar Berlin, without bold experimental films like Dr. Caligari’s Cabinet, expressionism is just a romp. Artistic movements come naturally out of a particular time and place. Once, German expressionism was political. Now it’s just as moderately entertaining as anything else.