Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

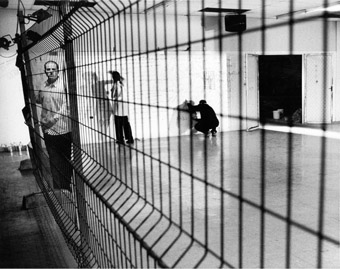

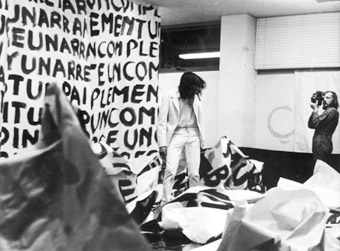

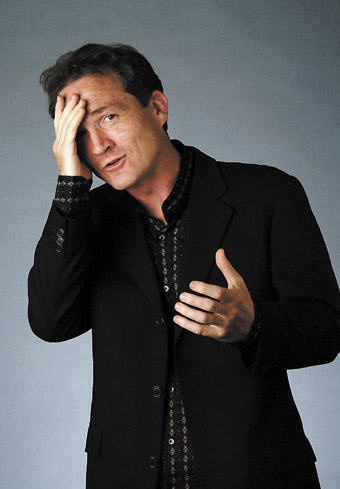

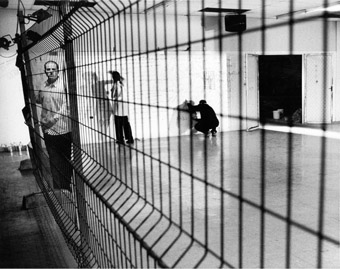

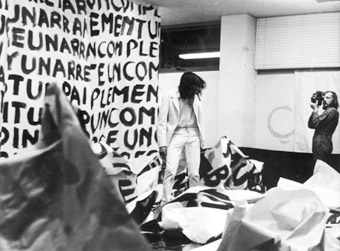

Mike Leggett filming Ian Breakwell in Unword

courtesy Mike Leggett

Mike Leggett filming Ian Breakwell in Unword

ONE OF SEVERAL PLEASURES TO BE HAD AT THE SCREENING OF FILMS BY MIKE LEGGETT AT ACP WAS THE SHOWING OF AN EARLY WORK FROM HIS UNWORD SERIES. THESE FILM ENGAGEMENTS WITH PERFORMANCE WORKS SERVE AS ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTS AND CREATIVE ACTS IN THEIR OWN RIGHT.

In 1969-70 in London, Bristol and Swansea, Leggett filmed Ian Breakwell in performance as the artist moved amidst huge swathes of inscribed material. The black and white shots with their photographic image intensity, staccato editing and sharply shifting perspectives against an instructional voiceover (language lessons and eyesight tests) create a curious visual rhythm but leave an incredibly strong mental imprint of the performance. Leggett filmed each performance, projected the footage as part of the subsequent one, and filmed that one in turn.

Leggett explains in his catalogue that the rhythm of the screening was not the result of editing: “The projection of the footage was on a Spectro stop frame analysis projector (a scientific examination tool) running at two frames per second.” In 2003 he and Breakwell “digitally reconstructed the Unword film at 2 frames per second, with a married soundtrack of the compilation tape.” Leggett’s Unword series covers the years 1969-2003. He tells me he has put them on DVD for study or reference.

The other highlight of the night was Shepherd’s Bush (1971, 16mm, 15 mins), a remarkable film which begins in black (has the lamp blown?, you think), the soundtrack pulses mechanically, the black lightens to grey to slowly reveal barely discernable movement across rough ground, brightening to a glaring white, erasing the image, the beat intensifying. It’s a truly invasive, curiously beautiful sonic experience and a spooky exercise in visual denial but one nonetheless conveying a frantic sense of momentum. The process has been described as simple (“a forward tracking movement was printed at every available grade in the printer’s grey scale”, John Du Cane, Catalog of British Avant Garde Art, London, 1971), but the effect is profound.

The creative representation of performance on film or video can be interpretatively problematic but in Unword, in Wade Marynowsky’s Autonomous Improvisations v1 (page 24) and in some, if not all, of the Castelluci films (Tragedia Endogonidia: video memory by Cristiano Carloni & Stefano Franceschetti) screened in Sydney and Melbourne in 2006 (RT74, p37), documentation is transcended and the spirit of the work retained and furthered.

A Program of Films by Mike Leggett, hosted by Louise Curham, Lucas Ihlein, Teaching and Learning Cinema, Australian Centre for Photography, April 28.

Mike Leggett’s Shepherd’s Bush appears on the Shoot Shoot Shoot DVD Vol 1, British Avant Garde Film 1966-76, featuring films from the London Filmmakers’ Cooperative available through OtherFilm Bazaar, www.otherfilm.org. The late Ian Breakwell’s own films have recently been released on the BFI British Artists’ Films DVD series.

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 22

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

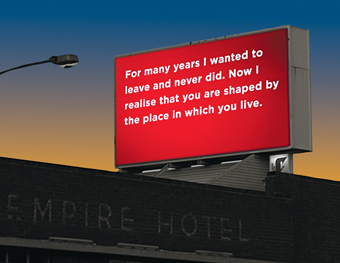

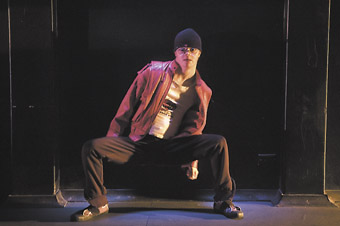

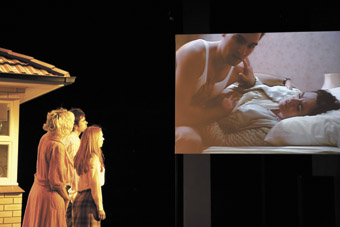

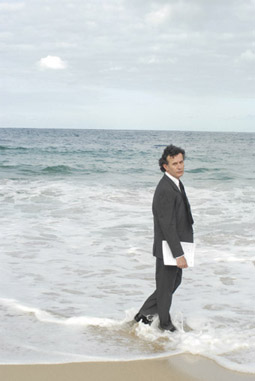

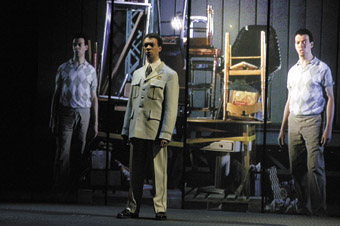

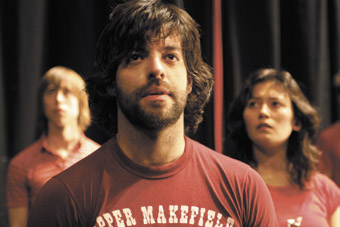

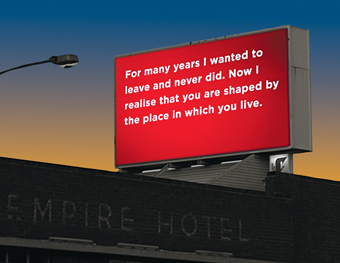

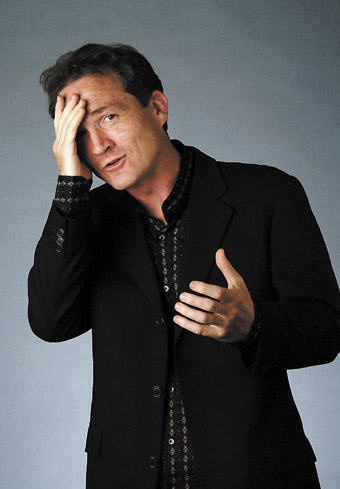

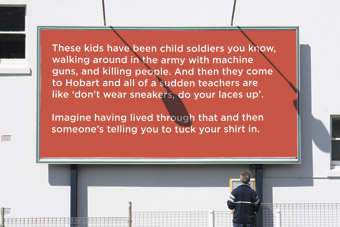

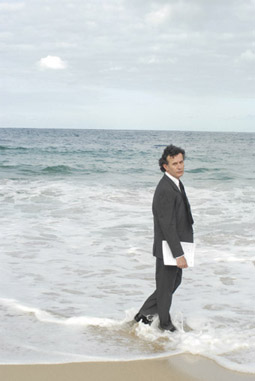

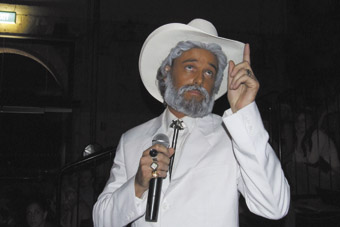

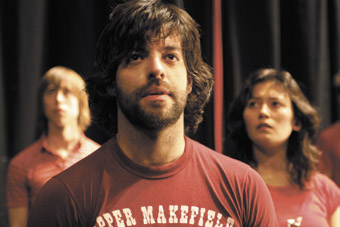

Daniel Frederiksen, Bastard Boys

BASTARD BOYS, THE ABC’S DRAMATISATION OF THE 1998 DISPUTE BETWEEN THE MARITIME UNION OF AUSTRALIA AND PATRICK STEVEDORES, INCLUDES A SCENE IN WHICH ACTU SECRETARY BILL KELTY, PLAYED BY FRANCIS GREENSLADE, ANOINTS GREG COMBET, PLAYED BY DANIEL FREDERIKSEN, AS HIS SUCCESSOR. LEAVING KELTY’S OFFICE, COMBET REMOVES HIS GLASSES AND FOR A MOMENT, WITH HIS SENSIBLE SIDE PART, RESEMBLES CLARK KENT IN SEARCH OF A PHONE BOOTH. THE TRANSFORMATION, THOUGH, IS NEVER REALISED. IN THE NEXT SCENE, COMBET IS PRETTY MUCH THE SAME MAN AS BEFORE.

In many ways, this transformation-that-isn’t is an apt metaphor for Bastard Boys: while it looks great, has an excellent cast and a compelling story, it never really flies. Rather, it remains grounded in a no-man’s land, trying to portray the complexities of recent political history on a tiny canvas: not quite drama, not quite documentary, it never manages to free itself sufficiently from the events of 1998 to offer a deeper reflection on the implications of those tumultuous events on the country.

These limits are strikingly apparent in the script, which often seems contrived to the point of silliness. In one scene, for example, Combet comes to convince a group of unionists to end a sit-in in response to the presence of scab labour on the docks. As he enters the room where the group of unionists has bunkered down, one of their number announces his arrival, adding “The ACTU. You ever heard of them? The affiliation of trade unions formed to devise policy and lobby on behalf of the labour movement.”

The producers might as well have plastered a caption on the screen to explain the ACTU and its role on the political landscape.

It’s not only the protagonists who get brushed with the bleeding obvious. Bastard Boys is infested with that blight of political drama: the set speech. Combet, for example, explains to union lawyer Josh Bornstein that “The law is an artificial construct erected by the capitalist class to ensure the system protects their own interests and maximises their own profit.” Later on, MUA National Secretary John Coombes, played by Colin Friels, explains the importance of solidarity to Combet thus: “I don’t break my promises, now that’s what solidarity’s about”.

While some of these exchanges are delivered with irony, they end up looking like clunky plot points and character sketches for those unfamiliar with the personalities and events around the waterfront dispute. Signposts of this kind are necessary to expand Bastard Boys’ appeal to more than political junkies, but they warranted a more sophisticated approach, not a high school social studies lesson.

These are symptoms of the larger problem of Bastard Boys, namely that in limiting itself to the particular personalities and events of the waterfront dispute, it remains a prisoner to the times and events it depicts.

In this regard, Bastard Boys might have been strengthened by displacing the point of view from the main protagonists in the dispute to minor players—the experiences of a scab labourer and a unionist, for example, would, potentially, have made for a more politically and artistically nuanced story. Alternatively the main characters and events could have been displaced to a different context altogether. A lesson here is The West Wing, which, rather than directly re-creating the Clinton Administration (which is its obvious template) displaces the action into fictional, yet recognisable characters and events.

While comparisons with The West Wing might be regarded as grossly unfair given obvious differences in resources, this isn’t an argument about production values or costs. The point rather is one of approach. A more visceral treatment, freed from particular characters and events might have given the makers of Bastard Boys greater creative freedom in expressing truths about those events which a more straightforward re-telling of events does not permit.

The political, cultural and artistic limits of the docu-drama format have been highlighted by the responses of the main protagonists that followed the airing of Bastard Boys.

Bill Kelty went on Late Night Live to complain that the show’s makers never approached him to ask about his role in the dispute. Chris Corrigan, meanwhile took to the opinion pages of The Australian to denounce what he saw as the portrayal of himself as an “evil, uncaring and insensitive boss” and to point to errors of fact around conspiracy claims.

The predictable nature of these responses suggests that rather than opening a space for a more searching discussion of the events of 1998 and their relevance to contemporary Australia, Bastard Boys seemed stuck in 1998. In an election year where industrial relations are set to take centrestage, Bastard Boys was an opportunity lost.

Bastard Boys, writer Sue Smith, director Ray Quint, performers Geoff Morrell, Daniel Frederiksen, Dan Wyllie, Anthony Hayes, Justine Clarke, Rhys Muldoon, Lucy Bell, Justin Smith, Caroline Craig, Helen Thomson, producers Brett Popplewell, Ray Quint; ABC TV & Flying Cabbage Productions; May 13, 14

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 23

© Christopher Scanlon; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

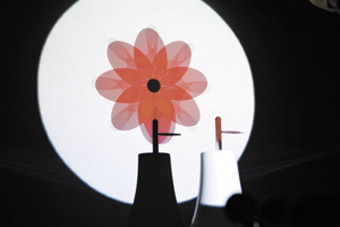

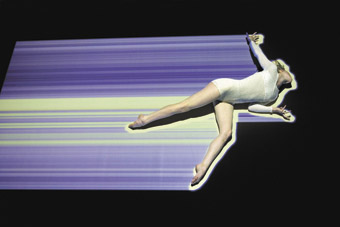

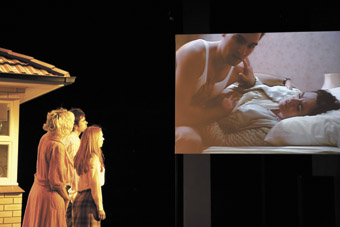

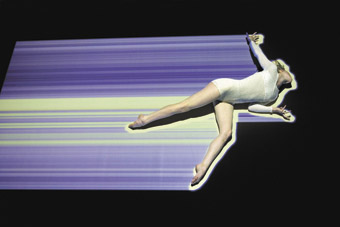

Lynette Wallworth, Hold: Vessel 1

photo Colin Davison

Lynette Wallworth, Hold: Vessel 1

LYNETTE WALLWORTH IS KNOWN IN AUSTRALIA FOR HER MUCH LOVED WORK, HOLD: VESSEL, WHICH HAS BEEN SHOWN AT THE ART GALLERY OF NSW, ACMI, DAVIS MUSEUM (USA), AND CURRENTLY AT THE NATIONAL GLASS CENTRE IN THE UK .

More recently Wallworth has been solidly foc sed on research and production for new works culminating in a series of high profile international exhibitions—at the New Crowned Hope Festival in Vienna, Arnolfini in Bristol, Auckland Triennial, the National Glass Centre, and the second exhibition for the newly launched BFI Southbank. The BFI have extended their commitment by commissioning a new stage for Hold. I caught up with Wallworth on the brink of a busy few months of production.

I am in the process of developing the work for the BFI so I am busy connecting with marine specialists I first encountered when working on Hold: Vessel 1. These are people like Marine Biologist Anya Salih who works on understanding the uses of the fluorescent gene in coral and David Hannan who first filmed the mass spawning event on the Great Barrier reef in 1990 and has been filming reef systems in all the years since. They are absolutely focused on corals, all of them in a slightly different way and they are the same people who informed my understanding then of the future stresses on marine organisms if current predictions of climate change held up. That was in 2001.

The issue of climate change was not in the public imagination then. Now I look at the footage in Hold and think, okay, I used this imagery of the giant kelp forests of southern Tasmania for example and only about five percent of those kelp forests exist now. So it feels a very potent time to be making this next stage of the work; it was something I always intended. The thing that has changed I think is the context. It feels to me as though everything I thought about in making the work has become transparent in the intervening years. To hold an underwater world in a fragile glass bowl gives a very clear, tangible sensation of these environments. It has become patently clear to most people that we really do have to think about what we are handing on to those coming after us.

It had always been in my thinking that the work would evolve, because marine environments are changing so rapidly, but it has been difficult to raise funds to make a finished work. The BFI, through Michael Connor’s curation, completely comprehended that this was a part of the work from its inception, this process of evolution and being able to walk through both the work and through different time spans. So it’s really a fantastic opportunity I’ve been given to continue it, and on the other hand it’s very confronting. It’s the strange sensation of making a work at a time when the impetus for the work has intensified.

Lynette Wallworth, Invisible by Night, 2004, commissioned by Experimenta

photo Colin Davison

Lynette Wallworth, Invisible by Night, 2004, commissioned by Experimenta

I always think that I make works that are communal at their core. I love looking at the way people who don’t know one another form a sort of temporary community whilst in the space together—there’s is something very anti-hierarchical about it. I certainly contemplate accessibility and the ability for people to be able to resolve the work with one another and I am interested in creating a tangible sensation of the audience being implicit to the work.

In a significant retrospective of her work At the New Crowned Hope Festival in Vienna, Wallworth exhibited five works including two new commissions.

Vienna was really one of the most satisfying times of my life. The curator Peter Sellars very carefully determined the way that you would move through the exhibition such that the relationship between the works became really apparent. Peter has worked a lot with Bill Viola and has a wonderful understanding about the best environment for experiencing these works. So he drew a map—I’ve still got this little serviette that I kept when, sitting in a café with him, very late one night in Vienna, he drew the journey from piece to piece. He is extremely attuned to things like how long it takes your eyes to become used to the physical aspects of being in a video installation.

My work is very slow in tempo and here was a way of placing things that supported the pacing needed and encouraged the sensation of immersion. I didn’t realise how obsessed I am with darkness until I saw all of these works together, but it is a very comfortable space for me. I am interested in how to construct darkness so you can rest in it, be altered by it. The other huge change in terms of the exhibition experience was that I had the support of FORMA [the Liverpool-based media arts agency], which has been a really significant breakthrough for me. For years I tried to find ways of getting my work produced in Australia but individuals can’t sustain a company that does this sort of work without funding. FORMA produce and tour for me so my life has changed. I feel now my practice is sustained and sustainable.

The opportunity to show in a festival is wonderful because of the focus on so many different art forms and artists—I got the opportunity to meet and talk with some of my favourites, especially filmmakers, as well as meet new ones. And the flow on has been great. There is interest in showing these pieces now in France, in Rome and in New York. Galleries are the best equipped to show it, but the festival environment gives the opportunity for the work to find relationships with other artforms.

The major new commission for Vienna was an interactive work, Evolution Of Fearlessness, for which I filmed 11 women, most of them political refugees. The experience of the work is a moment of ‘video meeting’ when the women respond to the viewer’s touch. In Vienna the relationship of this work to some of Sellars’ commissioned films was really interesting—the same medium with very different modes of delivery—and it sparked my thinking about where to go next. There’s an amplification that happens with this kind of attunement and that feels like a perfect home for me.

Prior to Vienna Wallworth spent three months on a British Council residency at the National Glass Centre in Sunderland, a chance for her to deeply examine the medium of glass, which she has used frequently in her work, and to develop new works combining video and glass.

Sunderland was very contemplative. It’s completely different working on glass than on a Mac G5. It made me think about the longevity of work. The history of glassmaking is a part of the experience of the National Glass Centre; it’s where the first stained glass was made in England. You can’t be there and not become cognisant of the historical importance of the medium. That haunts me really, because of the medium I work in. For example, the projectors we used to make Hold in 2001 are no longer in production, you can’t buy them any more and that’s in a six-year timespan. The software that we use to deliver work changes every year so it’s impossible to know how the work can be seen in 100 years time. Whereas a glass bowl that I made in Sunderland last year could still exist in that form, cracked and scratched, in a thousand years time. There is no economic determinant to make a piece of glass obsolete. This tension is inherent in the history of art, the experimentation with new materials and the concern for longevity. It really expanded my thinking about what are the essential tools.

The other thing that came from that time was that my work is still very strongly linked to being in the Australian landscape, so being in Newcastle (UK) for that length of time was quite challenging for me, but also helped to clarify why I still need to come back here to develop new pieces. It’s certainly easier for me overseas right now, my work is shown more and commissioning opportunities are definitely coming from Europe in a wonderful and supportive way. But I still find it beneficial to come home and make the work—there’s a fluidity about it, along with being able to work with the same people as a team. I think it makes the work much stronger. It means you can shorthand a lot of things and so take them in unexpected directions. But still, when I made Evolution of Fearlessness I imagined I would film women from other parts of the world, and I’m still thinking about that. It might be the one that actually shifts me out of this compulsion to make work out of Australia.

Lynette Wallworth, Hold: Vessel 2, BFI Southbank Gallery, London, June 23-Sept 2, www.bfi.org.uk. Touring produced by Forma, www.forma.org.uk

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 2

© Fabienne Nicholas; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

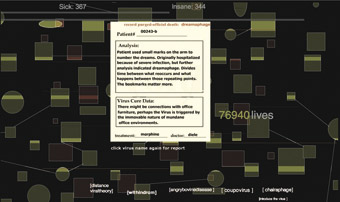

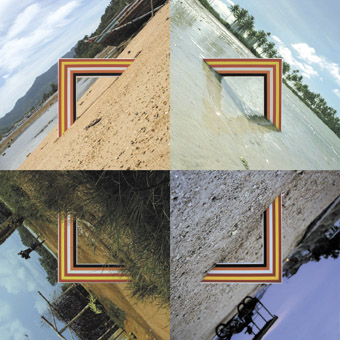

Field of Play, Digital Harbour

THE DOCKLAND DIGITAL HARBOUR AREA IS A DOUBLY VIRTUAL REALITY. COMPRISING THREE MAIN BUILDINGS (PORT 1010, INNOVATION, LIFE.LAB), BUT STILL TAKING SHAPE, EACH is MEANT TO EMBODY THE POSSIBILITIES OF AN INTERCONNECTED TECHNOLOGY AND RESEARCH CENTRE WHOSE PARAMETERS AND STYLE ARE YET TO BE REALISED. THE DOCKLANDS THEMSELVES ARE A VIRTUAL REALITY, MELBURNIANS STILL ATTEMPTING TO CONNECT A NEW URBAN SPACE WITH THE PRE-EXISTING CONCEPTUAL MAP OF A CITY GROWING LIKE IVY—IF IN A WEB OF STRAIGHT LINES. IN EVERY SENSE, THE ARCHITECTURE AND STREETSCAPES OF THE DOCKLANDS AREA ARE CONTESTED, VIRTUAL, UNREAL.

It is in this uncertain, unstable zone that Troy Innocent’s new work, Field of Play, toys with the abstractions of place and shape that form all of our sensations of location. In the shadow of these buildings, Innocent’s signs and colours of indeterminate origin coalesce and dance. Sets of paving stones are lit from beneath with colours and shapes, while a nearby wall acts as a neon Rosetta Stone, runes and letters from alien languages glowing in the dark. It takes only a moment to realise that a game is on offer.

Twin versions of the game, loosely collected around the concepts of ‘here’ and ‘there’, allow players to participate through the related website—or a powerful phone—controlling the lighted paving stones between the three buildings. The game uses the rules of Janken (rock-paper-scissors) to let players score points on a playing field of several either/or segments. Three players choose colours and hedge bets against the odds of being superseded by the colour above them in the cycle: green beats blue, blue beats orange, orange beats green. The game is playable on two planes of virtuality: online through the work’s website and secondly through the lights and paver stones of Digital Harbour, if you’re connected by a sufficiently powerful mobile phone. The second iteration adds an element of naturalism to the play, like digital divining rods bending with the promise of water as the lights below shift and rearrange in response to the twitches of your thumb.

Innocent’s conceptualisation of the game’s materiality is perhaps the most striking element. What seems to be Digital Harbour’s curious relationship to its own history as a docking port is suddenly illuminated as a zone of translation, transition and transaction. The three coloured lingua (orange, blue, green) of Field of Play are tied in Innocent’s formulation to electronic networks, digital games and tribal cultures respectively—avatar forms of the three surroundingbuildings. His previous works have also borne out this fascination with the properties of digital language, coalescing figures around the molecular drifts and eddys of the ether which we have become so accustomed to navigating.

Yet Field of Play takes on properties of this incorporeal dialogic previously undetected and uncelebrated with a ritualised and sacral tone. What was clearly envisaged as an enlivening of an open space instead broaches the implicit coda like a taboo. We are invited to embrace and then to play with the very artificiality of Digital Harbour. For a work so devout in its hermetic appreciation of the digital, players find their appreciation most satisfied by the soft warmth of the speakers and the heat of the luminescent pavers; concrete and glass also being kinds of virtual, remodulated earth. The sensory quality of the art, primary colours and heavy stone at your disposal through microgestures of the thumb and finger, enhances this ritual world.

Everything about Field of Play suggests a design that works during daylight but is more closely incorporated into the night lighting systems of the area. After several visits, the sensation of play transforms, especially during the traditional harbour activity hours of dusk and dawn, as the slate grey of the building is negated when bathed in colour.

Innocent’s digital explorations reveal a fascination with interfaces natural and technological, with the game as a carnival space confusing the two. Here, our playing is not a by-product of labour, or something we earn, deserve or waste. Instead, play is the inhabitation of an experience with a meaning beyond the messy materiality of the game’s duration. The ritual of the game lets even concrete pavers have a life of their own.

Melbourne Docklands Urban Art Program; Troy Innocent, Field of Play (2007), painted aluminium, custom luminaires, lasercut steel, shotblast pavers, multi-player digital game, computer-controlled light, four-channel sound; Harbour Lane, Digital Harbour, Melbourne Docklands, http://fieldofplay.net/

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 24

© Christian McCrae; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

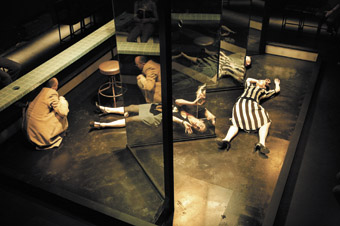

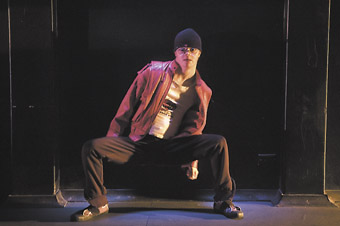

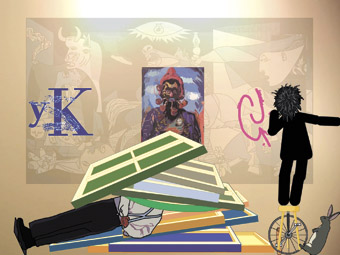

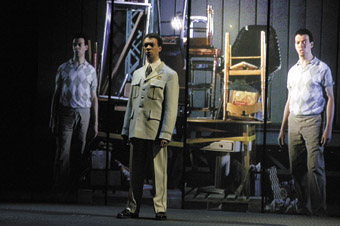

Wade Marynowsky, Autonomous, Improvisations v.1, L-R Lucas Abela, Toydeath, Matthew Stegh

photo Wade Marynowsky

Wade Marynowsky, Autonomous, Improvisations v.1, L-R Lucas Abela, Toydeath, Matthew Stegh

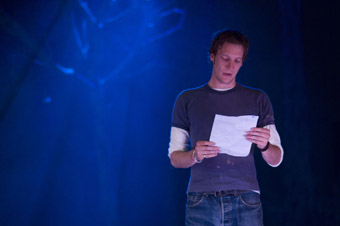

THERE’S SOMETHING STRANGE GOING ON IN THE BACK ROOM AT ARTSPACE, LOUD BURSTS OF CUT-UP NOISE AND WHAT SOUNDS LIKE THE FRENZIED EFFORTS OF AN ‘IMPROV’ PIANIST ARE COMING FROM BEHIND THE HEAVY BLACK CURTAIN COVERING THE entrance. INSIDE BY THE FAINT GLOW OF DIGITAL CANDLELIGHT AN OLD-WORLD PIANOLA PLAYS AND A BIZARRE PROCESSION OF PERFORMERS, MANY OF WHOM WOULDN’T BE OUT OF PLACE IN A CARNIVAL SIDESHOW APPEAR AND DISAPPEAR, PROJECTED ON THREE SCREENS.

Welcome to Wade Marynowsky’s Autonomous Improvisation v.1, an automated and prepared pianola that triggers an audio-visual mix of Sydney’s more infamous live performers, creating what the artist describes as “a mash-up of the ‘improv’ scene (the NOW now festival), the burlesque scene (man jamm), extreme metal-ists, techno-heads, toy-heads and the classical avant-garde…”

Roll up, roll up… for the fabulous transgender hula-hooper and the man who makes music using his mouth and a piece of broken glass…

If you live in Sydney you will probably recognise many of the artists who appear in this work and, as you might expect, there are lots of weird and wonderful looking people to behold. One hairy young man looks very much like he has just received a powerful electric shock and is covered from head to toe in red body paint. There’s a DJ in a polka-dot clown suit, a rapper in a gold gimp mask and matching lamé dress, and a man wearing little more than a few strategically placed plastic googly eyes stuck to his face, backside and crotch.

While the glamorous and glittery ones certainly stand out, many of the people on screen are more ‘regular’ looking music folk, some sitting earnestly behind their laptops, others twiddling knobs, swaying to theremins, mouthing into mikes and playing a range of musical instruments.

Marynowsky has assembled a diverse group of 37 performers creating a continuously surprising display of unusual collaborations and sonic arrangements. The artist explains he was aiming to create a mechanism that could juxtapose all sorts of people, “many who have never performed together and probably never will.”

While from past experience I know many of these acts make staggeringly loud or incredibly soft noises when performing on their own, the over all sound mix is balanced so that one never seems to take precedence over another. This restrained equilibrium means that combinations such as noise-core, tap dancing and soft vocals or minimal electronica, death-metal and rap can play simultaneously while still allowing subtle nuances from each to flutter in and out of aural focus.

The different performance images are all composed in the same way, giving a continuity that has the effect of binding them all together into one ‘live’ show. Every performer is alone in shot, positioned towards the centre of frame and lit vibrantly against a black backdrop. Each is very much in their element, onstage and demanding the focus of our attention to such an extent that it is often difficult to know where to look.

Sound and image bites jolt and collide as the performances captured on video are cut up and re-mixed on the fly in conjunction with the notes of the pianola. This digital mash-up gives the conjoined performances a strange inhuman rhythm and makes you wonder who the performer actually is in this situation.

Marynowsky has removed all but the trace of the human from this performative equation. The recorded liveness of the different acts is randomly triggered by an array of networked computers behind the scenes, but does this make it a new improvisation? And if so, whose? Who triggers the invisible pianola player—is it the artist or the computer, the programmer or the code? A bit of each I suspect, creating a new hybrid entity, a kind of musical bastard child, a freaky crossbreed.

In a playful and entertaining way Marynowsky’s work questions the notion of live performance and more specifically improvisation. What does it mean to improvise? Can a computer improvise? What about a group of computers programmed by an artist?

The work is a well balanced combination of live content, computer-triggered effects and kinetic sculpture. A testament to its composition is that the technology used is quite complex, but an understanding or awareness of it is not necessary to enjoy the work.

Apart from being a stimulating artwork, Autonomous Improvisation v.1 is a fabulous archive of the Sydney underground performance scene at the current time. Like a kind of digital documentary-automaton it continuously alters its form and is able to create a potentially unlimited supply of audio-visual experiences.

Wade Marynowsky, Autonomous Improvisations v.1, contributing artists Adrian Bertram, The_Geek_From_Swampy_Creek, Lucas Abela, Robbie Avenaim, Peter Blamey, Monika Pazniewska, Dallas Dellaforce, Jim Denley, Peter Farrar, Robin Fox, Brian Fuata, Dale Gorfinkel, Singing Sadie, Rev. Kriss Hades, Kristina Harrison, Ian Pieterse, Marty Jay, Josh Shipton, Hirofumi Uchino, Somaya Langley, Trent Mardan, Charlie McMahon, Dave Noyze, Shannon O’Neil, Gail Priest, Rory Brown, Mark Selway, Milica Stefanovic, Matthew Stegh, Amanda Stewart, Pizzo (George Tillianakis), Clayton Thomas, The Toecutter, Toydeath,Trash Vaudeville, Jon Wah, Dave Slave; Artspace, Sydney, April 20-May 19

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 24

© Anna Davis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

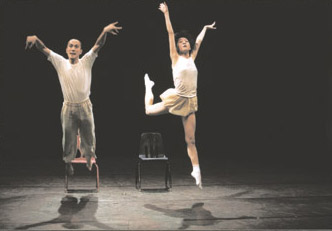

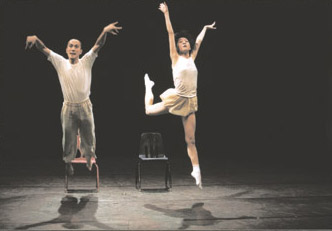

Valerie Berry, The Folding Wife

photo Heidrun Löhr

Valerie Berry, The Folding Wife

A DARK HAIRED WOMAN STANDS ON THE POLISHED FLOORBOARDS IN THE CENTRE OF THE NEW BLACKTOWN ARTS CENTRE PERFORMANCE SPACE. MUSIC PLAYS—NOSTALGIC MUSIC OF A FORMER TIME. THE WOMAN, VALERIE BERRY, UNDRESSES TO HER BLACK UNDERWEAR. TWO MEN APPEAR AND WITH THE FINESSE OF PUPPETEERS, BEGIN A LONG SLOW COSTUME COLLAGE.

They dress, drape and fold yards of fabric and clothing around the woman, morphing one costume into another—a peasant becomes a woman of class becomes a revolutionary becomes a political prisoner about to be executed. A machine gun strapped to a thigh, a radio spewing forth crackly sound is tied around her waist and her feet are forced into red high heels. Shoes, shoes and more shoes. We are in Imelda territory.

Paschal Daantos Berry and Valerie Berry, Australian artists, also siblings, born in the Philippines, first discussed a collaboration based on their shared history in 2002. Teaming up with Anino Shadow Play Collective from the Philippines, director Deborah Pollard and Urban Theatre Projects, they have produced a fine new performance work of biographical fiction called The Folding Wife.

Datu Arellano and Andrew Cruz, members of Anino Shadow Play and the men who have transformed Berry in chapter one, return to their workstation. As Valerie begins chapter two, they squat on the floor by an overhead projector and laptop and throw exquisite imagery onto the back wall. Like painters playing with liquid light, colour and form, they create the visual sensuality and texture of memory so powerfully evoked in the text by writer Paschal.

All I have is the view from this window. I have seen the century through this frame, seen them come and go…Our women have always been here sitting by the shadows waiting for new opportunities. Waiting for wars to finish…We can feign happiness with enough practice; it is in our blood, that’s how you become resilient—by bending and folding into recognisable shapes.

Valerie Berry’s impressively portrayed characters fold into one another through a non-chronological telling of chapters. Chapter two followed by chapter eleven, then by chapter five and so on. We meet Grandmother Clara, Mother Dolores and daughter Grace. We feel the heat and torpor of their lives as regimes and curfews come and go. It is a story of waiting: “…waiting for wars to finish. For our men to come home…” or a school child waiting for hours in the hot sun by the side of the road for a glimpse of Imelda Marcos, who never comes.

More ingenious shoe routines, and flags of different nations that spew forth from Berry’s mouth. Grandmother Clara pines for her Spanish past while urging her daughter Dolores to escape to America. Her advice: “If you have the misfortune to marry one of ours, always be a step ahead. Get to know the queridas (mistresses) and make their life a living hell.”

Dolores meets an Australian saviour instead: Arthur, who brings Dolores and daughter Grace, to a new land. “We are two, stepping off the Greyhound bus, wondering if the dust will ever settle. It is silent here. But if you prick up your ears you can hear blowflies.”

The atmosphere changes but loses none of its power. Dry yellows and sandy browns fill the screen as Grace describes arriving in a cultural desert. And yet in this barren place she blossoms and blooms. Here among the “rough and golden boys licking plates, cheeks varnished from lamb fat and tomato sauce, smelling of lanolin from the wool”, she becomes a woman, declaring, “I will never fold, I will never fold, I will never fold into my self.”

The length of gestation of the work and collaborative care director Deborah Pollard and team (including lighting designer Neil Simpson, production manager Alexander Dick and members of Anino) have given in creative development and production have yielded a delicious fruit. Sweet, sour, bitter—all the tastes of memory are present in this powerful work. The audience is left with sensual impressions of lace and blood, laughter and sorrow, “roasted corn on Sundays, coloured parasols reflecting the white heat of the sun” and a heritage of women, strong, beautiful and dignified, who have survived on memories of a glorious past or a projected future as they bent and folded into themselves a nation’s pain.

–

Urban Theatre Projects & Blacktown Arts Centre, The Folding Wife, performer Valerie Berry, writer Paschal Daantos Berry, director Deborah Pollard, design, multimedia Anino Shadowplay Collective, lighting Neil Simpson; Blacktown Arts Centre, Western Sydney, April 19-28

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 35

© Jan Cornall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jay Eusden, James Hullick, Cranky Robotics

photo Matt Murphy and James Hullick

Jay Eusden, James Hullick, Cranky Robotics

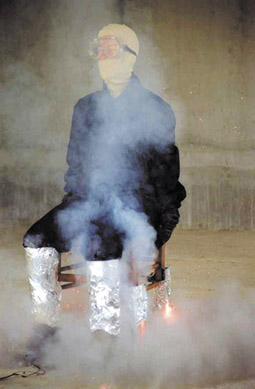

THERE ARE STRANGE NOISES EMANATING FROM THE STONE WALLED BASEMENT THEATRE OF THE FOOTSCRAY COMMUNITY ARTS CENTRE, PRODUCED BY AN ENIGMATIC ORDER SEATED IN HIGH-BACKED THRONES, GARBED IN HOODED BLACK JERSEY AND WIELDING MYSTIC POWERS OVER PRETERNATURAL CONTRAPTIONS. ENTER THE REALM OF JAMES HULLICK AND THE AMPLIFIED ELEPHANTS.

The Amplified Elephants have grown out of sound art classes run by Hullick for the ArtLife program which provides opportunities for people with perceived disabilities to experience a variety of artistic practices. Along with the Elephants, Hullick has invited instrument engineer Richie Allen and percussionist Eugene Ughetti to help bring the Cranky Robots to life.

The sound welcoming us into the space is a low machinic drone, like an insistent generator, shifting subtly through tones. Hullick and Liz Hofbauer approach the hitherto unattended mixing desk and start to tune the noise, releasing it to run wild, then catching and taming it, a tug-of-war between human and feedback revealing hypnotic drifting microtonal layers.

Hard on the heels of the sculpted onslaught, Enza Practico enters the space with wind chimes—the simplicity of action and sound working as an aural palate cleanser preparing us for the subtlety of Hullick, Ughetti and Jay Eusden’s study for microphones. Using feedback and effects, whistling, tapping and rubbing, the artists explore texture, surface and the tactility of the microphone, re-inventing it as a responsive poetic instrument, rather than a blunt tool.

These early pieces serve well as preludes to the Cranky Robots, defining an exploratory space where the behaviour of instruments is under serious scrutiny. The next piece, Secret Joy in the Wish Fulfilment of Love uses Whirling Dervishes—instruments made from a spinning metal bowl with a marble inside, activated by an adapted power drill mechanism. The sustained metallic resonance provides the bed for percussive exploration led by Ughetti. The piece, while subject to chance elements—like the marble flying out of the bowl and across the floor—is tightly structured, with Hullick conducting the action, teasing out pleasing layers from metallic drones and vibrations.

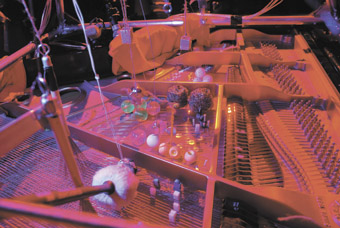

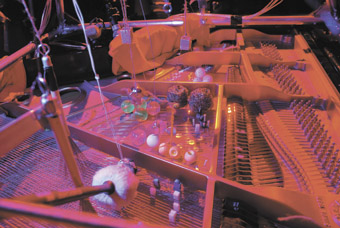

Cranky Robotics, prepared piano

photo Matt Murphy and James Hullick

Cranky Robotics, prepared piano

Particularly intriguing is the Pranky-Ano. Designed to annoy the ‘prima donna’ piano, this pyramidal structure is placed over the strings of the piano with a series of percussive objects strung from levers. Activated from a midi-keyboard, the levers—reminiscent of a giant old typewriter—lift and drop objects onto the strings. At the same time Hullick plays the piano creating delicate gamelan tones, rudely interrupted by percussive agitations. Together the artists and machines become the ultimate prepared piano, a kind of Cagean-cyborg.

The Pranky-Ano developed from the Crank-A-Maphone which, strung like a monster mobile with wind-chimes, wooden boxes, bowls and other resonant junk, has a percussive focus. It too is midi-activated for this concert, which allows each of the Amplified Elephants to play a section in the final work. The piece is tightly structured around sections of Cranka-A-Maphone semi-random cacophony, and the quieter explorations of Ughetti on percussion, the clarity of sounds creating a kind of acoustic pixelation.

Along with the ingenuity and engineering of the machines, Cranky Robotics was impressive in the attention to structure within each piece, utilising every artist’s ability and expression to its optimum and finding a fine balance between control and chaos. The imperfection and unpredictability of the machines offered challenges but also freedoms within compositional process as did the various abilities of the artists defining an intriguing space for exploration—a space for serious play and gentle provocation in which every action is guided by a genuine desire to engage, express and work together to create a little bit of magic.

Cranky Robotics (Jolt Concert 1), director, sound designer James Hullick, percussionist Eugene Ughetti, instrument engineer Richie Allen, Amplified Elephants June Bentley, Jay Eusden, Liz Hofbauer, Robyn McGrath, Enza Practico, lighting Geordie Barker; Footscray Community Arts Centre, Melbourne, May 6

The Jolt concert series continues June 24 with Ernie Althoff, Robin Fox and James Hullick and July 22 with Hullick, Fox, Philip Samartzis and Myles Mumford; bookings Span Community House 9480 1364

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg.

Van Sowerwine’s Small Beasts

STILLS, IN ITS CAPACIOUS CONVERTED WAREHOUSE IN SYDNEY’S PADDINGTON, HAS BEEN A RARE COMMERCIAL SUCCESS IN art PHOTOGRAPHY, FEATURING A STRONG STABLE OF AUSTRALIAN ARTISTS, EXPORTING THEIR WORK AND INTRODUCING OVERSEAS ARTISTS TO AUSTRALIAN AUDIENCES AND BUYERS. I MET WITH OWNER-DIRECTOR KATHY FREEDMAN, CO-DIRECTOR BRONWYN RENNEX AND CURATOR SANDY EDWARDS TO DISCUSS JUST HOW A COMMERCIAL PHOTOGRAPHIC GALLERY HAS ADAPTED TO THE AGE OF PHOTOMEDIA. ALTHOUGH THEY COME FROM DIFFERENT BACKGROUNDS AND HAVE IDIOSYNCRATIC TASTES, THE TRIO EXUDE A COLLECTIVE PASSION FOR THEIR ARTFORM, PICK UP ON EACH OTHER’S THOUGHTS AND PASSIONS, COMPLETING OTHERS’ SENTENCES WITH AN EASY FAMILIARITY. THEY DECLARE THEIR SHARED COMMITMENT TO AN EVOLVING MEDIUM AND TO THE ESTABLISHED ARTISTS THEY REPRESENT AND THE EMERGING ONES THEY SEEK OUT.

The current Stills exhibition features sculptures (small dog scale) made by Van Sowerwine with accompanying photographs of the same creatures in their natural habitat, pockets of lush bush in an urban setting. You approach one on its plinth, sneak a touch of its soft, pink skin and peer into a wound-like hole on its forehead where you glimpse miniature video images of the creature’s thoughts—foliage, other beasts and a slurry of moving brain matter. As usual with Sowerwine this is a grimly comic experience, if certainly less dark than previous works. Van Sowerwine’s creatures may be cute and toy-like but they are also alien presences. In an adjoining space we watch bracing, raw black and white videos on screens large and small by US artist William Lamson of thwarted human endeavour where, for example, a man tries to keep pace with a giant paper dart flying over him on a nighttime landscape. This combination of photographs, sculpture, video and installation is now part of the photographic gallery experience, and although the phenomenon has been in evidence for quite a while, it is currently in a state of acceleration.

adaptation & survival

Kathy Freedman recalls that the move in 1997 from a small terrace house to the former film studio which now houses Stills was motivated by a need for space in which to show large scale (an enormous image by Emil Goh in the opening show), multimedia works (a Merilyn Fairskye video installation in the same show) and series of images (Pat Brassington). But it was only this year that Stills invested in a large video monitor: “We’d managed to get by without owning the equipment until now—it was the artist’s responsibility to chase it up”, says Edwards, to which Freedman adds, “we need to commit if we are seeking out artists working with the moving image and for our existing artists who are starting to.” But there’s a larger issue at stake.

“To survive as a gallery,” explains Freedman, “we needed to attract a lot more collectors of contemporary art, people who see photomedia and photography as embedded in contemporary art. We just don’t have the population in Australia of people who collect straight photography.” This has also meant broadening the kinds of artists Stills represents, “something we anticipated 10 years ago as photomedia began to move to the forefront of contemporary art. But it’s only in the last three years that we’ve been really moving in this expanded area—Merilyn Fairskye had been our main artist working in moving image and installation.”

Edwards comments that Rennex “has had a lot to do with that, tuning into the people doing work of that nature. Kathy and I come out of a slightly different tradition and a majority of our artists continue to work in still images mounted on walls.” To which Rennex adds, “and there’s still a lot to get out of people working that way.”

Freedman thinks the market for moving image is growing: “shows like the Anne Landa Award at the Art Gallery of New South Wales are good for this. We took on Van Sowerwine after seeing Play With Me, shortlisted in the first show. This is the first William Lamson showing in Australia; he’s still reasonably young.”

emergence

Rennex says that in expanding the range of artists and the kind of works Stills engages with, the gallery “has used its first exhibition for the last two years to feature emerging artists—this year Peter Volich with his framed football jerseys with small found photos, Daniel Kotja’s installation and photographs and, the year before, Martine Corompt with her vinyl wall pictures and projection and Van Sowerwine with her crank-handle animation. This first show of the year for me has been about opening the door a little more—still photos are just one part of photomedia now.” Freedman recalls that there was a time “when we felt constrained by the photograph on the wall. Now there’s a problem we’ve been grappling with, our name—Stills. What name could we adopt that would reflect what we’re doing?”

digitally unreal

When I comment on the magic of recent digital photography, its heightened detail, unusual texturing, painterliness and various effects, Edwards makes the observation that “in the past we thought we had a notion of what was real in a photograph, but now the digital realm has created a situation where people come at the image from another angle, asking, Is this a photograph? They no longer believe in the veracity of the photograph.” Freedman adds, “Everything is read as digital now.”

Many photographers now work digitally, but not everyone, says Edwards citing the example of Stephanie Valentin “who uses an electron microscope to put words on pollen grains and then photographs that.” “You think it must be something created digitally”, says Rennex, “but it’s not.” Edwards explains: “The old processes still remain in the mix. Valentin is using a method equivalent to a photogram (when you place an object on the paper), but she’s putting the object in front of a projector and passing light through it. It hits the wall, it’s made large—so she’s inverting the scale—there’s nothing digital, it’s all manual, but mysterious.” Rennex mentions that Christine Cornish “who once would have laboured over a silver gelatin print, produced her last show using pigment prints—but Pat Brassington and Robyn Stacey have been working digitally for a long time as part of their whole process.”

“We have great fun with Pat Brassington’s images”, says Freedman, laughing, “asking, What is that thing, that disgusting thing? Looks obscene. But Pat rarely tells us. If she does, it’s an incredibly prosaic description—a sock filled with something.” Edwards describes Brassington “working with her negatives from the past, whatever’s there, whatever mess is on the negative, scanning them and creating a whole new object in the computer. So it’s about her imagination in relation to the past, which we don’t know about and she doesn’t want us to.”

selecting & selling

The trio agrees that selecting and taking on an artist is very personal. Freedman recalls Rennex putting forward Roger Ballen [RT 75, 52] with his dark humour and strangeness: “I looked at the book and thought I love this work, but I don’t know if it’s going to sell. In fact it has sold to institutions and private collectors—not all of them work from that particular show.” It was the first serious look at Ballen in Australia; for some “he came with a reputation and a number of books”, says Rennex, and for others, says Edwards, “the response was immediate even if they hadn’t heard of him.”

Edwards praises Freedman “for never showing just on grounds of commerciality. You don’t know what’s going to take off. You go on your instinct and interest and love of the work and you wouldn’t want to be showing anything you didn’t like. Success reveals itself over time. Certain artists rise to the top as good sellers, and we’ve got a fair few of these and you depend on that. Then others come in and you grow them and they get picked up or not. There are so many factors…Artists “see us as a lifeline—it’s a very mutual relationship.”

balancing acts

Freedman says running Stills is all about balance—established/emerging, national/international, photography/photomedia—but also “the balance of our personalities.”

I ask the trio to talk a little about their relationship with photography. Kathy Freedman tells me, “My background is in psychology and I worked for many years as a psychologist before taking on the gallery. What I notice in me is gravitation towards quite disturbing works. There certainly needs to be some sort of emotional, not necessarily overt, content that stays in my mind—Brassington and Ballen appeal in particular and Trent Parke’s Minutes to Midnight series, which has been my favourite work of his—a travelogue of Australia but a view of its dark side.”

Sandy Edwards describes herself as “coming from a traditional documentary background and it’s never left me. I still love the image. And also, having been a photographer, learning how to make perfect images, expose and print them correctly, never quite leaves you. I still see the skill in making an image which is an imprint from the world in some way. There’s a huge range of work within that category and I’ve got particular tastes in it, but I still love the image on the wall that tells you about the world we live in.”

Bronwyn Rennex says she “responds mostly to work that suggests ruptures in civilisations or failures—because photography is so often used to sell things and to make things appear perfect. It’s always a relief for me when there’s an idiosyncratic voice that speaks about imperfect things or that escape social structures. Lamson is an example of work about failure—a reminder of what it is to be human. And it’s in my own work, about things that run under the surface. In Always Hungry (2001), the very act of trying to satiate oneself is self-defeating. The more you want the less you have. And for me the shadow self is more honest than the surface self.”

Despite these different perspectives, Rennex says that the trio’s tastes often coincide. “There’s quite a big overlap”, Freedman confirms. There was, for example, unanimity on the forthcoming Magnum 60th Anniversary show which includes Alec Soth (USA). Rennex says “He captures not just Niagara Falls but the mythology, the hopes and dreams laid on that place.” His work reminds Freedman of Wellington-based Anne Noble’s Antarctica (Stills, April-May 2006) which looked on the surface like a straight documentary but “juxtaposed images from Noble’s Antarctic residency with those of museum dioramas representing that polar world.”

photomedia ecology

The trio feel that sharing audiences and market with other galleries is a good thing for Stills and for photography in general. Rennex notes that “the MCA has had a lot of photography shows in recent years and arts magazines have been focusing on it.” Freedman mentions Roslyn Oxley9, exhibiting photography for many years, and the Sherman and Gitte Weiss galleries, and says, “the major institutions have been incredibly supportive of us and our artists.” Edwards sees this spreading connectivity as “a slow growing relationship—we’re in touch with the key curators and there’s a lot of to-ing and fro-ing, discussing things. Australian photography has been enjoying a heyday in the last 15 years in the way that Gail Newton (NGA) was fighting to achieve in the early days. Photography is now up there with any other medium and has realised itself. As a result a lot of artists have chosen to work with photography.”

Freedman comments, “it was a divide, between photographers and artists who work with photography.” Edwards enlarges, “There was a big politic there but it has moved on a bit. For example, a lot of group exhibitions have brought documentary back into the field after it had been excluded for a while and now documentary’s manifesting in very different ways. These photographers have got wise. They’re using large scale images and installation.” “They’ve evolved too, necessarily”, adds Rennex. “To the extent I’m happy about doing the Magnum show. It feels like a real shift”, concludes Freedman.

www.stillsgallery.com.au

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 41

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

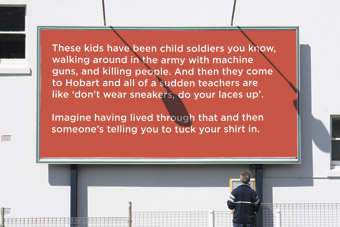

Swingers

AT A TIME WHEN THE FUTURE OF THE TRADITIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IS A MATTER OF SOME DEBATE, TWO OF AUSTRALIA’S NEWEST FESTIVALS ARE FORGING AHEAD. WHILE ADELAIDE HAS JUST SEEN ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL EVENT BOTH CRITICALLY AND IN TERMS OF ATTENDANCE, PERTH’S REVELATION FILM FESTIVAL IS ABOUT TO CELEBRATE ITS 10TH BIRTHDAY WITH A LARGER AND EVEN MORE INNOVATIVE PROGRAM, MORE FILMS AND A NEW ARTISTIC DIRECTOR. MEGAN SPENCER, DOCUMENTARY MAKER (LOVESTRUCK: WRESTLING’S NO. 1 FAN; RT78, p20) AND FILM CRITIC FOR TV AND RADIO, HAS LEAPT ENTHUSIASTICALLY INTO THE TASK OF KEEPING REV ONE OF THE MOST IMAGINATIVE AND CHALLENGING ANNUAL EVENTS ON THE SCREEN CULTURE CALENDAR.

While the more established film festivals are trying to adapt to new ways of looking at cinema, and still grappling with the rather delicate balancing act of satisfying their older, subscriber-based audiences with more traditional offerings while attracting the very necessary newer and younger audience with diverse and provocative programming, younger festivals don’t have this challenge. Their audiences are risk-taking, attracted by innovation; these events can grow organically with their audiences, can enjoy the new ways of both making and experiencing the moving image.

Unlike the larger and more traditional film festivals, which developed naturally from the film society movements or from a city or a community’s need for such an event, the Revelation festival emerged from a desire to screen underground films from all over the world, and a need to take cinema into different environments. Now the event is very healthy; it has state and federal government support through Screenwest and the Australian Film Commission, triennial funding, and a strong sponsorship base.

Rev began in 1997 as an underground event in a basement, Perth’s smoothest jazz venue, where it screened everything on 16mm and included live music and poetry. On its tenth anniversary—titled Revolution. Retrospective. Revelation—Rev will screen around 100 features, documentaries and short films, as well as music videos and experimental work, include a late-licensed festival club and other music and film related activities, and present them at both established cinemas and at nightclub venues. Rev hasn’t abandoned its underground beginnings: Cinema Tabu will present a microcinema showcase of strange films from around the world in a bar environment. Brent Hoff from San Francisco is editor of Wholphin DVD Magazine (an offshoot of cool literary journal, McSweeney’s) and gathers together rare and unseen films to release on DVD. He will screen a selection of these as part of Cinema Tabu.

Already a filmmaker and reviewer, Spencer hadn’t been planning to look for a job as artistic director of a film festival. When she actually considered accepting such a role, however, she realised that every experience she’d had “coalesces and becomes relevant. I’ve got the benefit of being a filmmaker, and of knowing what filmmakers want and hope to get from a film festival. And I’ve seen thousands of films. I’m aware of the cultural and critical connections. I understand the lie of the land and I think I know what to program for the audience to connect with.” And, she says, becoming artistic director of Rev is really a natural progression. “I’ve cheered it on as an exciting new event, I’ve had films screened there, I came over to Perth twice with SBS’s Movie Show. I think I understand what the audience wants.”

Unlike most festival directors, she hasn’t been able to travel to overseas festivals to put her program together. Instead, she’s been programming from the internet, through other festival websites, festival reviews, and the many new avenues offered (“MySpace has been a very good source”), while Rev’s growing identity has, of course, made it attractive, with over 500 films submitted for selection from local and international filmmakers. Working closely with Rev founder Richard Sowada (now Head of Film Programs for the Australian Centre of the Moving Image in Melbourne, but still chairman of the Rev board and very involved) in choosing films, she’s particularly excited about the queer cinema strand, which includes John Waters’ Pink Flamingos (1972), Anna Biller’s Viva (2006; a parody of 60s sexploitation films) and Mary Jordan’s documentary, Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis. “I’d never heard of him—I was just stunned when I saw the film. It’s amazing when you discover someone like that, and other filmmakers fall into place.”

Spencer hopes the activist strand will encourage at least some audience members to, well, become active and do something. There’s Iraq For Sale (2006) by Outfoxed (2004) director Robert Greenwald, on war profiteering; God’s Ways, by German filmmaker Evan Neymann, on two street kids in Odessa; and Soft Words, an Australian short film by Adrian Francis on political spin about asylum seekers and how it abuses language. Rev’s strong documentary strand this year includes something Megan Spencer is particularly excited about: a mini-retrospective of the work of famed documentary-makers the Maysles brothers, with two short films showing Truman Capote and Marlon Brando in a fresh and unexpected light.

Super 8—that little film gauge that just won’t go away—is the surprise element in Rev’s 10th birthday, forming the basis of the new film competition, Revel-8. (“The more we go forward in time, the more incandescent Super 8 becomes”, comments Spencer.) Former director of Perth’s lost and lamented Pandora’s Box Super 8 Film Festival and ECU lecturer Keith Smith takes charge of this new event celebrating the fusion of image and sound, inviting both experienced and novice filmmakers resident in WA to participate. “Super 8 is the original DIY medium and is still finding new devotees after 40 years of glorious imaging. It’s not just the unique look, there’s something magical about working on Super 8 which brings out a special creativity”, he explains. Filmmakers are challenged to make a silent, unprocessed film, edited-in-camera, on a single Super 8 cartridge, lasting just three and a half minutes, on the theme, “Birthday”, using an experimental, animation, drama or documentary approach. Then the best 20 films will be scored by composers at the WA Academy of the Performing Arts and screened in a 5000W flickfest at the Rev Club on Friday July 20, with lots of creative and genre prizes on offer.

A major element of the festival is the Screen Conference, which was initiated last year as a space for filmmakers and those involved in many aspects of the film industry to discuss and workshop a range of related issues. This year the conference has grown, and its guest list includes representatives from the international distribution scene, local and international filmmakers, composers, editors, cinematographers and writers. Featured conversations, masterclasses and workshops include two sessions on HD Heaven (a masterclass with Toby Oliver ACS, on working with HD); Art of the Music Video, with both an international and local focus; The Art of the Short Film; Loving the Alien: The Relationship Between Documentary Filmmaker and Subject; Shedding Light: Performance For Screen; and DIY or Die on digital filmmaking and alternate modes of exhibition and distribution.

Special festival guest and anime proponent Phillip Brophy will be presenting Tezuka: From Manga to Anime, on how Osamu Tezuka transformed his manga into anime. Rev is screening Brophy’s curated program, Focus on Tezuka (already seen at the Art Gallery of NSW and ACMI), with its kids’ flicks component of Astro Boy and Kimba The White Lion, and five fantastic adult animations. Brophy will also be represented in his filmmaker and sound design artist mode; during the festival he’ll be performing The Planets, a remixed presentation of his exquisite cinema scores live, and screening his Evaporated Music series of big-budget, high-gloss video clip images reworked to monstrously alien sound. And his notorious sci-fi horror comedy from 1993, Body Melt, will have a rare screening.

Strange Culture (2007) is a convention-defying documentary by Lynn Hershman Leeson which screened earlier this year at the Sundance and Berlin Film Festivals. It documents the extremely paranoid reaction of US security authorities in the case of internationally acclaimed artist and professor Steve Kurtz when his wife Hope died in her sleep of heart failure. Police arrived, became suspicious of Kurtz’s art, and called the FBI. Within hours the artist was detained as a suspected ‘bioterrorist’, his computers, manuscripts, books, his cat, and even his wife’s body were impounded, and he still awaits a trial date. While Strange Culture manages to reinvent an old form while telling an urgently topical story, what makes it even more memorable is that the Sundance Film Festival screened the documentary in Second Life, the first feature film to be screened on the online community. Rev will not only be screening the film, but will also include a panel on Second Life as part of the Screen Conference—Second Life and Beyond: Virtual Communities and Making Media in a Digital World, organised by Mick Broderick.

Megan Spencer hopes that her first festival will continue the great work that Richard Sowada has done in making Rev a very distinctive event. Sowada himself is cautious about the future for film festivals: “a not-for-profit event has to exist in an exhibition culture that’s commercially based, that’s totally geared to making money. Rev is all about audience development, and that’s a very difficult area to navigate right now.” Spencer thinks that “what makes Rev special is that it opens up a dialogue with the individual filmmaker, and brings in people from all aspects of filmmaking. What I’m trying to do is blur it all: see how digital culture is affecting film, how much feature film has taken from music video—and vice versa. It’s important to recognize what’s going on, and to discuss and debate it. I believe in plugging film into film culture, rather than the industry, and I think that’s what Rev does.”

Revelation Perth International Film Festival 2007, July 12-22, www.revelationfilmfest.org

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 21

© Tina Kaufman; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jonathan Dady, Cardboard Pianos, installation,

Jonathan Dady, Cardboard Pianos, installation,

There Forever, Port Adelaide

What are the markers of this great age of hybridity? In the arts they are transience, transformation and sensory transport in works that heighten our sense of ephemerality, of mutability and, with apparent magic [digital and otherwise], shake loose our perceptual certainties. In There Forever, Jonathan Dady’s cardboard pianos exhibited in a deserted shop in Port Adelaide [page 4-5] evoke the fragile, even surreal aspirations embodied in the incipient regeneration of an old suburb. In Merilyn Fairskye’s video work Stati di Animo [p3], past and present likewise co-exist in the moment, in a dynamic of stillness and motion—the photographic fixity of waiting airline passengers juxtaposed with the ghostly brushstrokes of those on the move. In Aqua [cover image], Fairskye’s new work for Stills Gallery, the video image of a swimmer is layered some 50 times, each image a second apart, generating an intensely fluid impressionism—‘now’ and ‘then’ constantly folding into each other. Whether in the works of Dady and Fairskye or in Jia Zhang-Ke’s feature film, Still Life [p17], where we are invited to look in real time rather than surrender again to the edit, or in Craigie Horsfield’s enigmatic “slow time” photography [p41], or in Chris Marker’s Owls at Noon [p27], or in the Wooster Group’s replay and recreation of Richard Burton’s 1954 made-for-television Hamlet, it is above all our sense of time, perceived visually, aurally, spatially and filtered through many media, that is radically undone.  Jonathan Dady, Cardboard Pianos, installation,

Jonathan Dady, Cardboard Pianos, installation,

There Forever, Port Adelaide

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 1

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

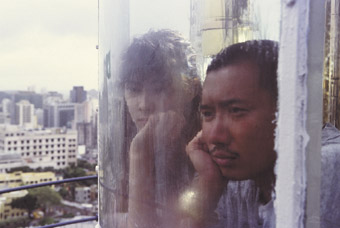

Merilyn Fairskye, Stati d’Animo (States of Mind), 2006-2007

courtesy of the artist

Merilyn Fairskye, Stati d’Animo (States of Mind), 2006-2007

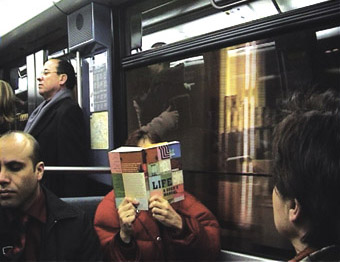

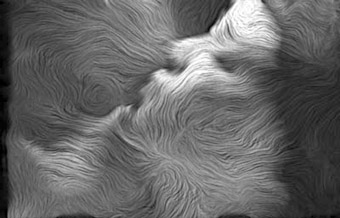

MERILYN FAIRSKYE’S STATI D’ANIMO (STATE OF MIND) EVOKES THE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT EXPERIENCE LIKE NO OTHER ARTWORK I CAN RECALL. THE THREE-SCREEN WORK THAT WRAPS AROUND YOU AT ARTSPACE FUSES AT LEAST TWO STATES OF BEING INTO ONE. FIRST, THERE’S WAITING, WITH ITS SHEER STILLNESS, HERE A PRECISE PHOTOGRAPHIC FIXING ON THOSE SITTING OR STANDING. THEN THERE’S MOVEMENT, THE PURPOSEFUL STRIDE OR ABSENT-MINDED WANDER, REALISED CINEMATICALLY AS A GHOSTLY BLUR OF BODIES WALKING, RIDING ESCALATORS, HAULING THEIR BAGGAGE. THOSE WHO WAIT APPEAR FROZEN IN TIME, THOSE WHO MOVE SEEM ALWAYS ON THE EDGE OF DISAPPEARING. THE NOWHERENESS OF AIRPORTS AND THE SENSE OF ETERNAL TRANSIENCE IS RENDERED EVEN MORE PALPABLE IN THE WAY FAIRSKYE GIVES BUILDINGS, EQUIPMENT AND AEROPLANES THE GREATER SOLIDITY—HUMANS ARE A MERE EPHEMERAL PRESENCE.

With her Sony HDV camera hand-held, mostly at waist level, Fairskye recorded at Charles de Gaulle, Darwin, Dubai, Frankfurt, Helsinki, Hong Kong, JFK, Kuala Lumpur, Los Angeles, Pudong, Sao Paulo, San Francisco, Singapore, Sofia, Sydney and Vienna airports. She writes, “the camera moves or rests without composing or focussing on the people it tracks and traces” in a work that is not “investigative or ethnographic documentary. Nothing specific is revealed. The aim is to achieve a sense of things, of simultaneity, rather than a direct account or story.

“The formation of the interior airport images in this work is different from conventional film and photography. It closely resembles the sequenced exposures of chronophotography by Jules Etienne Marey which (like Henri Bergson’s reflections on time) inspired the painterly experiments of the Futurists that this work evokes. The effect is to condense and dilate the experience of time, by superimposing a sequence of frames in fifty transparent layers.”

This layering allows Fairskye to conflate time so that we are watching past and present at once folding into one another: “the ‘present’ is thus continuous (and coexistent) with the past, in a perpetual state of becoming and vanishing, in the same way as the people who briefly inhabit the airport, and the airspace above it, become and vanish.”

Merilyn Fairskye, Stati d’Animo (States of Mind), 2006-2007

courtesy of the artist

Merilyn Fairskye, Stati d’Animo (States of Mind), 2006-2007

The association with Futurism is quite precise—the title is taken from Futurist artist Umberto Boccioni’s 1911 trilogy of paintings which has the railway station as its zone of transience. Painting and train station are replaced in Fairskye’s work with digital art and airport, the joys and anxieties of machine age speed paralleled with those in our own time to do with computer speed and hyperconnectivity. But the vulnerability of bodies and machines persists, not only in the visual ephemerality of Fairskye’s airport inhabitants, but in their words.

Structured into passages of Arrival, Crossing, Waiting, Departure and Farewell, the video watches but also listens. What appears to be airport background noise is revealed to be something more: at one point the attentive listener is privy to a dialogue between airline cabin staff on one plane and the control tower—a terrorist drama appears to be unfolding in the cockpit. The aeroplane moves across the tarmac and then, when air control says, after communication is broken, “We’ve lost them”, the jet simply disappears against the background of buildings and other aeroplanes. Life in the airport terminal goes on, with its alternating solidity and blurring.

I asked Fairskye about about the technical side of her work which, she writes, “is quite simple but chews up a lot of render time. I had already sorted out the process in principle when I made an earlier three-channel Stati d’Animo installation (Stills, 2005, shot on SD and working with 25 layers only). Greg Ferris worked on post production for Stati d’Animo 2006. The new material was shot on HDV. Once the offline edit was completed, all the interior airport shots were each subject to the following process.

Merilyn Fairskye, Stati d’Animo (States of Mind), 2006-2007

courtesy of the artist

Merilyn Fairskye, Stati d’Animo (States of Mind), 2006-2007

“A template was set up in After Effects for 50 duplicate layers of video (going to 50 from 25 made the image much more fluid.) Each layer was moved along one frame. So overall, there was a time overlap of 2 seconds by the end of the particular shot. The opacity of each subsequent layer was decreased according to a formula I have worked out so that by the time you got to layer fifty there was still a visible trace of all the preceding layers, including layer one, but from two seconds earlier. This is an aspect of the process that is crucial from my point of view—a visualisation of a temporal depth that is quite different from linear duration. Lastly, the whole thing was rendered, and imported back into Final Cut Pro as a single track video, and colour corrected. With my new work, Aqua, I am doing everything in Final Cut Pro, greatly assisted by the Paste Attributes command.”

Fairskye’s new video work Aqua (see our cover image), premieres soon at Stills Gallery as an installation. I had a glimpse of the video in preparation. The look and feel, quite different from the gently fluent if eerie time shifts of Stati d’Animo, is of an intense vibrancy, a living impressionism and, again, magical play with technology and perception.

Merilyn Fairskye, Stati d’Animo (States of Mind), 2006-2007, three-channel video installation, writer, director, producer Merilyn Fairskye, camera, post production, sound Merilyn Fairskye, Greg Ferris; Artspace March 16-April 14

Merilyn Fairskye, Aqua, Stills Gallery, Sydney, July 18-Aug 18

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 3

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

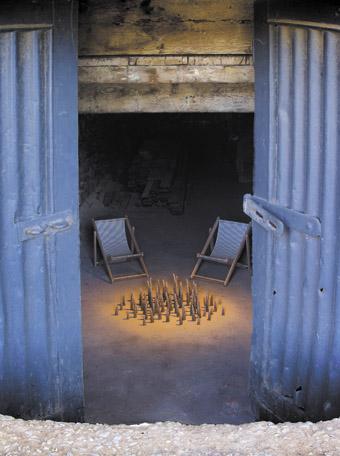

Angela Valamanesh, New Metaphors

photo Anton Hart, image courtesy of artist

Angela Valamanesh, New Metaphors

“PORT ADELAIDE—IT’S HAPPENING!” READ THE SIGNS AROUND THE LARGEST WATERFRONT URBAN DEVELOPMENT BEING UNDERTAKEN IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA OVER THE NEXT DECADE. IN THE VISION AND FRAMEWORK DOCUMENT FOR THE NEW CITY, JAN GEHL, PROFESSOR OF URBAN DESIGN, TALKS ABOUT PORT ADELAIDE IN RELATION TO OTHER RECLAIMED WATERFRONT CITIES IN THE WORLD AS “JUST WAITING TO BE RECONQUERED. “ HE SEES THE CENTRE AS HAVING “LOST ITS CONNECTION TO THE WATERFRONT…THE WORKING HARBOUR IS IN THE PROCESS OF BEING TRANSFORMED INTO A RECREATION HARBOUR WITH THE OPPORTUNITY TO REINVIGORATE PORT ADELAIDE CENTRE AND RECONNECT IT TO THE WATERFRONT.”

Transforming this historic city has unearthed predictable disputes to do with insensitive development. Hoping to generate more complex discussions around what constitutes a sense of place, artist and local resident, Linda Marie Walker responded to her strong feelings about the Port with an “ephemeral public art project” entitled There Forever. As part of the Port Festival, the event involved eight artists creating works that each in their own way addressed the subtle striations of history that are potentially warped in any major urban re-design.

“The title refers to the idea that everyday attention, deliberate action, and continual work is required in relation to the infinite memories and physical bearings of a place to ensure that these remain as part of a place’s past and future”, says Walker in her curatorial statement.

Yhonnie Scarce traces the trajectory of Fanny Graham, an indigenous woman born (1925) at Point Pearce Christian Mission on the York Peninsula and buried there (1967), who spent part of her itinerant life in the Port. The artist creates a kind of map, sewing coarse red thread onto tough black canvas, in the process engaging with people moving through the Visitors Centre. At the climax of the event, she will fold the cloth and place it beside the paper dress pattern and white gloves in the suitcase which lies open on the floor of the project headquarters in the old ANZ Bank building in Lipson Street.

Julie Henderson has taken up residence for a time down at the harbour, slowly acquainting herself with some of the people who gather and work in the sheds and shacks there. Her DVD, installed in the door of one of the boatsheds, documents the artist’s conversation with the boat builder who has worked there for years. His face never appears, only his body and the materials of a craft to which he is clearly devoted. Ambivalent about the luxurious life his boats may go on to enjoy in one of the Port’s proliferation of planned new marinas, the boatbuilder says of his boat’s new owner, “I think he called it Georgia.”

Nearby is the Radio Shack in which Henderson has spent long periods listening to men from the amateur radio club. She’s filmed their idiosyncratic environment and recorded their conversations and documented one man transmitting a message in Morse Code (he chose “the moving finger writes and, having writ, moves on…”). Henderson also stages a performance at night on the site of the old shed 5 (“Look for two lights, bring an umbrella”).

Inside the shack, Julie Henderson says she can’t quite settle on what constitutes the art of this project. On the website she muses: “Perhaps the work is impossible or perhaps it is already there and I just need to notice its formation among other things. I am in the space of the swamp, the dock, the boat-builder and the amateur radio club and I’m localizing and taking small opportunities to meet them. I’m in their place—it is an open shape with details that we inhabit together for now.”

As in all the works in There Forever, a sense of quiet and detailed evidence-gathering pervades amidst the more urgent atmosphere of impending disappearance. As part of the redevelopment, and lacking obvious “heritage” status, the Radio Shack may be razed anytime soon, like the nearby boat sheds.

Elements of the works that can be pinned down form an intriguing exhibition in the bank building which is the project’s HQ. Denuded of all but its elegant proportions, this house is full of subtle surprises.

In the ceiling of one room, Jess Wallace’s video, Buoyancy, references the buoys in the river that have been out of bounds since 1869 by Declaration of the Marine Board Act. Wallace projects young swimmers flouting the law, as kids at the Port have done for years, freely floating them above our heads.

Jonathan Dady, The Cardboard Piano Shop;

photo Jonathan Dady, image courtesy of the artist

Jonathan Dady, The Cardboard Piano Shop;

A wall away, in perfect light filtered through large windows and reflected off the buff colours of the paint-stripped house, Jonathan Dady’s elegant cardboard piano makes silent music. Down the hall, Julie Henderson’s harbour video sits atop a 1960s TV set transmitting interference from the Radio Shack.

Downstairs, James Guerts’ Bridge Drawing Water displays the beginnings of the artist’s collection of casual markings gathered from the wharf and drawn onto the walls of the house. Another surprise— one stair tread is painted gold.

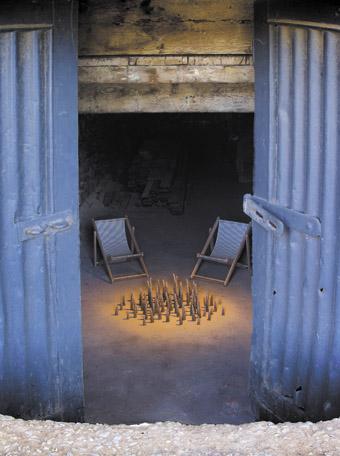

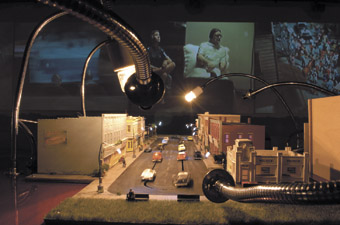

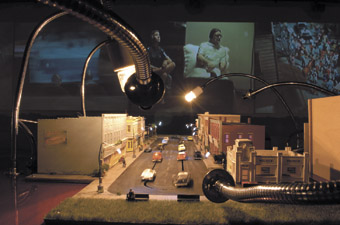

Angela Valamanesh’s New Metaphors began in the mangrove sites once pervasive around the Port but now almost invisible. In the basement below a studio in Divett Street, she installs a small drama. Peering down from the street, we are faced with two miniature deckchairs addressing a series of clay replicas of pheumatophores—aerial roots of mangroves that grow above the low tide level to allow the plants to breathe. Says Valamanesh “I’ve been wondering why mangroves are of interest to me as a visual artist. I think it’s that they are plants that live in both water and land and have characteristics which visually link them to human and animal life.”

Jonathan Dady’s proliferating pianos make another appearance, this time displayed inside a graceful disused shop on the main street. Starkly lit, and randomly displayed, they maintain their sense of grandeur—prototypes perhaps for the aspirations of a working class area gradually succumbing to gentrification.

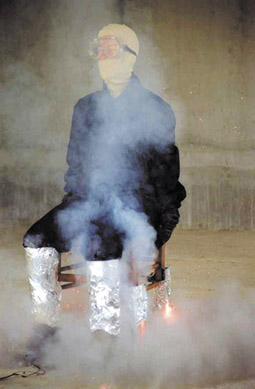

Michael Yuen, Flash

photo James Geurts, image courtesy of the artist

Michael Yuen, Flash

Among the performance works which my sole foray precluded attending was Michael Yuen’s Flash: “At this place and time for a brief moment a large flash of light and burst of sound will saturate the surrounding region. The point of origin will be the Port Adelaide Lighthouse.”

And throughout the nine days of the event, Teri Hoskin was travelling (on foot, by car and train) each day at daybreak and dusk from her home in Adelaide to a series of pre-figured locations in Port Adelaide. She took from these “points of perception” and posted on the web a series of images and sounds, adding to her ongoing assembly of “useless knowledge” valued solely for the role it plays in the minute everyday of life (http://ensemble.va.com.au/9days).

Last night the bridge opened to the sound of breathing under water. It closed again, the two sides met ungainly, like this sentence.

There Forever, various sites around Port Adelaide, curator Linda Marie Walker, artists James Geurts, Bridge Drawing Water; Jonathan Dady, The Cardboard Piano Shop; Julie Henderson, Continuous Wave, Forms For A Dialogue; Michael Yuen, Flash; Jess Wallace, Buoyance; Teri Hoskin, B Part Renaissance; Angela Valamanesh, New Metaphors; Yhonnie Scarce, Fanny Graham; The Port Festival, Port Adelaide, April 21-29

RealTime issue #79 June-July 2007 pg. 4,5

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

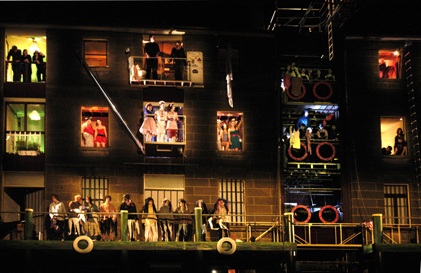

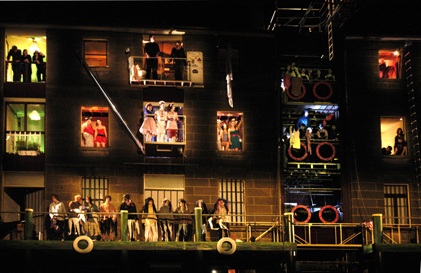

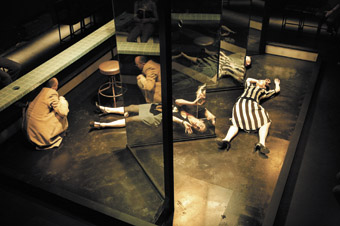

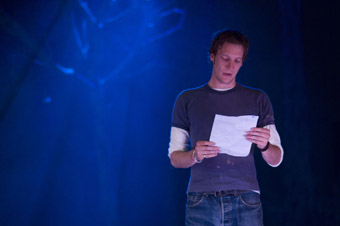

The Wooster Group, Hamlet

photo Paula Court

The Wooster Group, Hamlet

GROWING OUT OF THE CREATIVE AND POLITICAL FERMENT OF THE DOWNTOWN NEW YORK ART SCENE IN THE EARLY 1970S, THE WOOSTER GROUP HAS REMAINED ‘A THEATRE COLLECTIVE’ LONG AFTER AUSTRALIAN GROUPS BORN OF THE SAME IMPULSES SIMPLY GAVE UP THE STRUGGLE AND FADED AWAY (THE AUSTRALIAN PERFORMING GROUP BEING THE MOST OBVIOUS PARALLEL). INDEED, IN THE CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN CONTEXT, THE IDEA OF A ‘COLLECTIVE’ SEEMS ALMOST OUTRÉ, SUGGESTING A PROJECT BOTH NAÏVE AND IDEOLOGICALLY OVER-DETERMINED. BY CONTRAST, THE WOOSTER GROUP HAS MAINTAINED A SENSE OF INTELLECTUAL PLAY AND ENGAGEMENT WHICH READS AS FRESH, VIGOROUS AND UNAFRAID—AND AS RELEVANT TODAY, IN THEIR PRODUCTION OF HAMLET, AS IT WAS WHEN I FIRST SAW THEM IN 1986. FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS THEY HAVE SUSTAINED AN EXPLORATION OF THE POSSIBLE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PERFORMER, TEXT AND MEDIA TO CREATE AN EXTRAORDINARY BODY OF WORK WHICH HAS BEEN CONSISTENTLY ENTERTAINING AND RIGOROUS.

The Wooster Group’s longevity seems even more remarkable when you consider the company has had only one director—Elizabeth LeCompte—working with a core group of powerful personalities (including Willem Dafoe, Kate Valk, and formerly Ron Vawter and Spalding Gray) and a shifting roster of associates. Taking into account all the mundane problems of maintaining a theatre company, such as ever increasing salaries and production costs and the fickleness of critical fashions, as well as the potentially explosive combination of creative personalities, it’s easy to imagination that either exhaustion or implosion would have put paid to the company a decade ago.

However, the Wooster Group appears to have found a strategy which has allowed a visionary director and a company of strong-willed performers to work together for what for many has been an artistic lifetime—even as one of the core members of the group (Dafoe) has built a career as a mainstream, if minor, Hollywood star. And unlike her contemporaries (Twyla Tharp say, or Arianne Mnouchkine), LeCompte remains relatively in the background: she is clearly a formidable character, but seems content to let the performers be the public face of the company. (Mnouchkine’s shock of grey hair and steely gaze I recall from her watchful presence before and after performances by Theatre du Soleil, but despite interviewing LeCompte in the late 80s, and having had the privilege of seeing the company perform on at least six occasions since then, I cannot for the life of me remember her face!)

The Wooster Group oeuvre includes “nineteen theatre pieces, four dances, three radio plays, five video/film works, and the first eight monologues of Spalding Gray” (www.thewoostergroup.org), and will soon include an opera when they take on Cavalli’s La Didone, via a collision with “Mario Brava’s 1965 cult movie Terrore nello spazio.” The collision of a classic or overburdened theatre text and an obscure ‘cult’ film is a typical starting point for a Wooster Group production. The violent encounter of mediums, performance styles and histories produces the rich multi-modal performance language which defines the company’s style, a hectic, always surprising collaging of personal and public histories, pop cultural references, performance techniques and media.

newly mediated old hamlet