Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

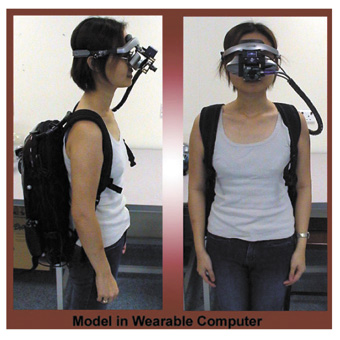

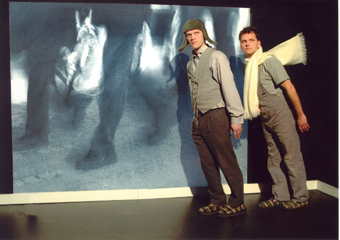

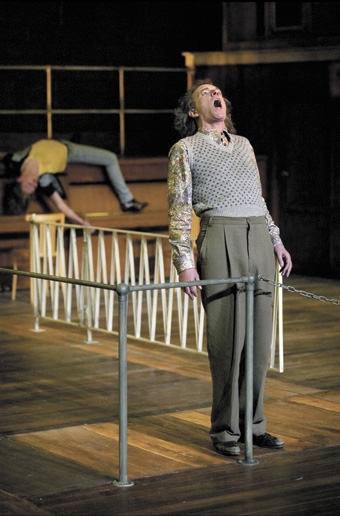

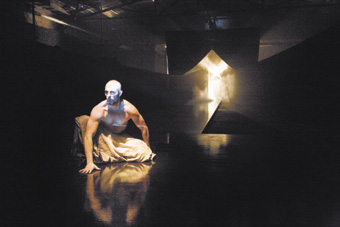

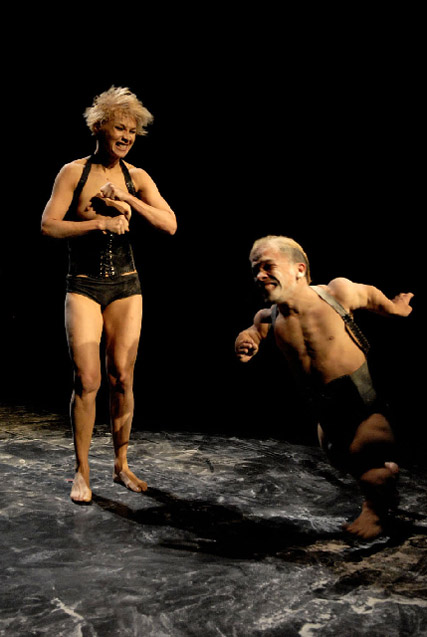

Dream Masons

photo Michael Rayner

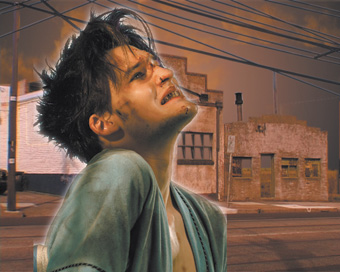

Dream Masons

To the oom-pa-pa of the band water cascades from the stage, shadow-puppet fish swim in the windows of Salamanca Arts Centre, a boat floats above the street audience and performers climb ladders and moving ramps on a uniquely vertical stage. These impressive theatrics leave you smiling. Dream Masons is worth attending just to observe the amazing set design that turns the façade of the Arts Centre into a stage with unlimited opportunity.

The rigging is fantastic: ramps appear out of nowhere allowing performers to scale the building; a washing line strung between windows allows a performer to swing from one to another; and skilful wiring allows a fisherman to row in mid-air. Projections and shadow play reveal scenes and sub-plots further accentuated by the deftly changing music score as each window lights up.

Mood is largely dictated by the music and lighting, and most of the characters are defined by their musical accompaniment. The excellent small cabaret-style band, comprising tuba, drums, keyboard, bells and accordion, generate the ominous quality of a scene with a whale that would make Hollywood directors jealous. And many members of the audience cannot help but bop to the more upbeat music.

The building is populated with clown-like stereotypes: the helpless bourgeois lady in a wheelchair, the woman hanging out washing and yearningly holding up a wedding dress; the muscular sailor showing off his strength to a ditzy girl; and the ‘old hag’—a woman with a hunchback. The characters visit or intrude on each other or party—until the plumbing goes wrong. This is where the production comes to life. The building is flooded, resulting in an evacuation to the top storey providing suspense and interest so far lacking in the production. The water rises, fish and shadowy water demons and finally a giant whale appear, impressively filling the windows of the entire façade.

After the initial introduction to the building and its inhabitants, large banners had been unfurled to announce the five chapters of the story, revealing the production to be an allegory of the flooding of Lake Pedder. (Really! What did the first part of the production have to do with this?). For me Dream Masons relies a bit too heavily on glitzy stunts and theatrics, dated gender stereotypes and a trivialising of the Lake Pedder disaster to form a coherent and convincing story. However, the design, with its vertical staging and clever use of windows, rigging and lights was fantastic; so let’s hope that this approach is used again in the future in a more coherent production.

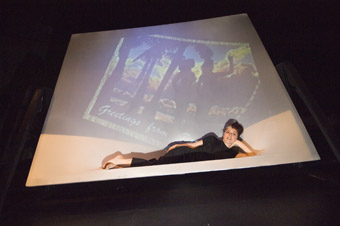

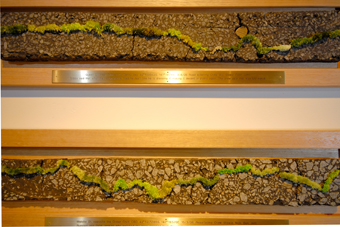

Lucy Bleach, Circumnarrative

photo Craig Opie

Lucy Bleach, Circumnarrative

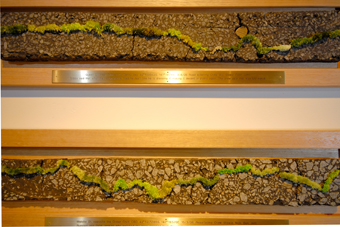

A low wooden structure snakes around the pillars of the Long Gallery. A series of plaques on the wall proudly display fragments of local roads. An easily missed lightbox hides outside the gallery window. This is Lucy Bleach’s Circumnarrative.

The wooden structure is probably the most puzzling of the three works. Two parallel lines of 10cm high plywood curve around the timber floor forming the likeness of a walled road or some other passageway. It dodges the gallery pillars in a way that a plant would, the organic nature of its movement suggesting that nature may have been an inspiration. Yet it still looks very much built, with its exposed supports and its likeness is to roads which track a journey through what appears to me to be the gradually evolving shape of Tasmania. I strain to remember the locations of the roads I have travelled in my own short time in the state: Eaglehawk Neck, Burnie, Launceston.

Lucy Bleach, Circumnarrative

photo Craig Opie

Lucy Bleach, Circumnarrative

The five plaques mounted vertically on the nearby wall each display a section of bitumen dug up from Hobart roadworks. Between the cracks, delicate green embroidery pokes out, just as hardy plants would amongst the urban landscape. Engraved professionally below each section on a brass plaque are the details of the location of the road, its coordinates, the date of the removal of the section, the names of the crew, as well as quotations from people involved in the works or looking on. These observations fight the cold objectivity of the plaques, some describing an experience relating to the road: an old man who named the particular crack in the road which he has been watching for many years “Nellie.” Other sentences are brutally honest: “Bumped into Pete Jenkins who watched the crew scraping back the road with me and told me Mary had lost their baby girl.”

The third work, the lightbox mounted outside on a neighbouring wall depicts a landscape view with a freestanding gate, through which can be seen the edge of the land over the ocean. Even without the gate, the typically bleak Tasmanian landscape would seem hostile; but the gate adds an extra physical barrier to the land. It is also cleverly placed out of reach in the space between the buildings—an island of colour and light against the sandstone wall.

Circumnavigate is an initially incohesive work, but on closer reflection, the three parts share an underlying theme. I perceive an outsider’s view of Tasmania. As with many small communities, Tasmania has a cliquey nature that many newcomers to state find initially alienating and hostile. Perhaps, coming from Sydney, Bleach has experienced this ‘outsider’ phenomenon. The wooden structure may suggest the roads of Tasmania, but also a sense of exclusion: these ‘roads’ are created out of relatively tall barriers, preventing not only entrance but also escape. The wall plaques share with us intimate comments, but are presented in a strangely objective manner, suggesting the view of another kind of ‘outsider.’

Circumnavigate is beautifully mysterious: the structure which evolves as you walk around it and consider the shape of the whole and the journey within; the intriguing plaques with the fleeting stories of ordinary Hobart workers and the overlooked remnants of their efforts made permanent; and the landscape, sectioned off twice in a bid to keep out the stranger. It takes time to enter Lucy Bleach’s work, however the reward is coming to a unique understanding of Tasmanian as ‘an other place’.

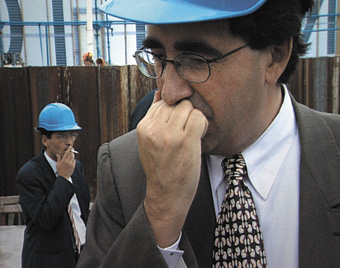

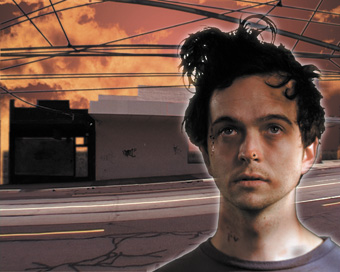

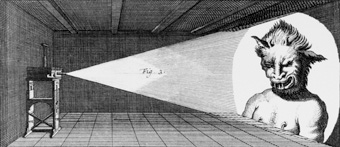

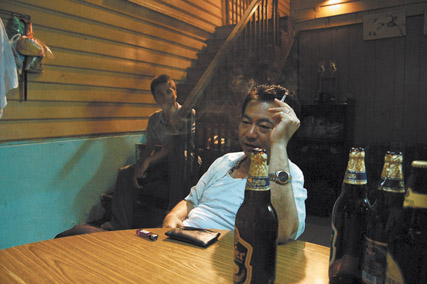

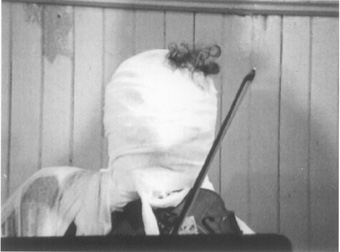

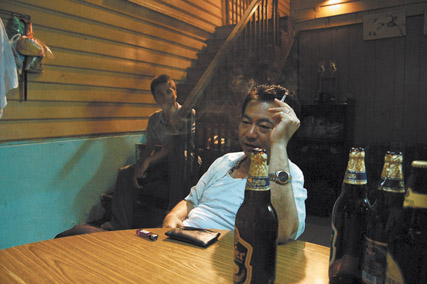

Austin McQuinn’s Bogeyman

photo Craig Opie

Austin McQuinn’s Bogeyman

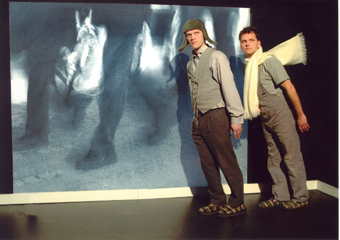

There’s a neverending conversation in much artwork that emanates from Tasmania and is about Tasmania, which is about This Place (a current local advertising campaign virtually orders us to Love This Place!) that was eventually named Tasmania, after being Van Deimen’s Land for a period of time, and presumably had an Indigenous name before that. There is a particular sensation that the place seems to evoke, formed by distance, being dwarfed and awed by a landscape huge and even intimidating. The South West Forest (possibly the most internationally well-known part of Tasmania) was named Transylvania on early maps, setting into motion a strange unnamed kind of Tasmanian Gothic that has dominated much artistic production here ever since.

Austin McQuinn’s Bogeyman offers a particular vision of this place, a vision of Hobart, that is familiar and Other at once. A video projection introduces us to an odd figure constructed from dark cloth that covers the entire body except for the head, which comprises a clump of those old woollen CWA toys made into a slightly sinister amorphous blob. Interestingly, the use of old toys is fairly common round here, due in part to the presence of the Resource Tip Shop. The regular Art From Trash exhibitions usually feature something like the Bogeyman’s headpiece. But there’s more to this Bogeyman than his appearance.

He wanders out of place, pathetic and forlorn through regions that for me are rich with personal memory. I know the region of the mountain Bogeyman stands in, the steep street in South Hobart he carefully feels his way down, looking ever more awkward and displaced. I know which courthouse he’s been in, and I wonder if his story is formed in part by the sad tale of the Irish political exiles that ended up here. The guy who made the work is Irish after all, and for the purposes of this exhibition, the Irish are apparently Other as well.

So, the Bogeyman is alone in a place that I find so familiar. He doesn’t have my local know, is blind to the resonance and ripples that he creates, re-writing the landscape with his small presence. It’s a landscape he’s removed from—he can’t see, all his sensory equipment muffled by the thick black costume and the heavy headdress. He’s been made that way—he is a construction.

I see the places he’s in as some of the most obvious places an outsider would go when they come here; then I wonder if I’m being smug and insular. Maybe. Maybe I’m tired of the same story of this place being told by those from outside it. That’s if it is the same story, but if it is not, why do I recognise it? Even some things about the Bogeyman seem familiar. The way he seems to be put together, made out of residue, discard and children’s nightmares. I’ve seen him before somewhere; somewhere here. He’s unfamiliar and yet sympathetic in his lonely plodding. And I do think of him as character, yes, somehow. Somehow he takes that on in this work, bringing me back to where I sit, staring at him, wondering if his mere presence has re-written my home town even for me. I watch him sadly slide under a bed that no one sleeps in anymore.

That’s it. He was under my bed. He was under yours as well. Remember?

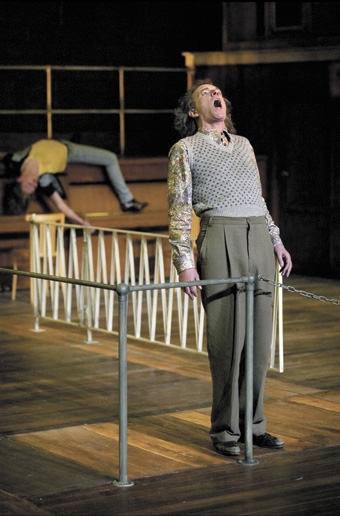

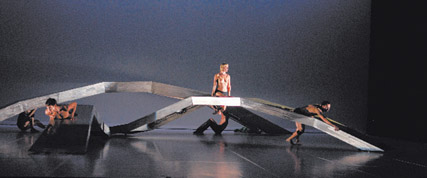

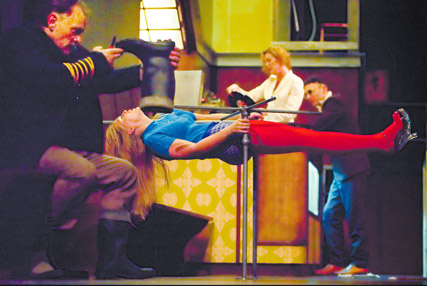

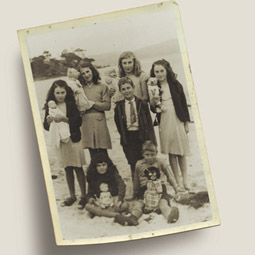

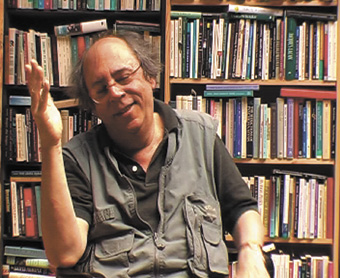

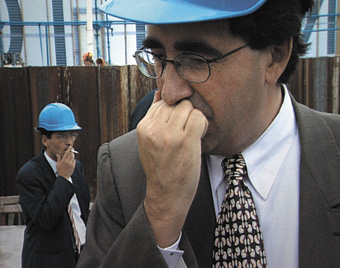

Andy Jones, To the Wall

photo Michael Rayner

Andy Jones, To the Wall

It’s immediately and alarmingly clear that you’re locked in a room with an eccentric. You’re a captive audience. You pray it’s a non-participatory one. Newfoundlander Andy Jones comes on, an engagingly pushy mix of lecturer, spruiker and preacher, flogging a thesis that will explain why humans are so bad to each other, and what we and God, should he exist, can do about it. The extrapolation of the thesis, he advises us, will take the whole performance. In the meantime he kicks off with something terribly contemporary—anxiety about anxiety, specifically the human wiring that triggers: “future possible, possibly horrible” (which he titles fitposs, economising from a French-Canadian rendering). We’re all very attentive and the brisk texturing of references French, Irish and Newfoundland layers the thesis-making with something very particularly cultural and possibly personal—as in Jones’ droll description of his intensely exclusive Roman church upbringing as “Hasidic Catholic.”

Most of the time fitposs (“a déjà vu of the future”) prepares us for the worst, but September 11, 2001 shocked the atheist Jones into prayer—what else could you do, he asks. This plunges him into a big question—are we God’s experimental failure (God wanted equals, got nasty supplicants and is profoundly lonely, and therefore absent)? He offers some big solutions—let’s invite God to a public meeting, in this theatre, tonight, and propose some genetic tweaking. Without fitposs we might be a nicer species (Jones rattles off a history of the demise of earlier humans not fitted with fitposs—the first of our kind were, of course, Adam and Eve). While modifying our anxiety generator might seem a reasonable idea, Jones is not reasonable in any ordinary sense, suggesting that we have anxiety thermostats visibly implanted over our nipples (slide of Uma Thurman at an Academy Awards thus technically adorned). This will not only make us more aware of each other’s emotional fluctuations but generate some new language: “Go fluctuate yourself!” Wilder evolutionary engineerings are suggested later in the show, but in the meantime there’s much else to rapidly absorb and to reflect on: what would be the saddest story you could tell a rabbit such that its tears would turn to ice and lock it to the ground (and provide you with dinner)?

This is discursive theatre, Jones playing out a persona doubtless rooted in the real man and stylistically reminiscent of the American Spalding Gray, if without the incantatory poetry or darker personal musings, and the UK’s Ken Campbell (Jones was a performer for a period with the Ken Campbell Roadshow). Like Campbell, Jones is in love with the big picture, generating wildly improbable theses that nonetheless tell us much about what worries us and the kinds of not always silly fuzzy logic we apply to such mysteries. Again like Campbell, there’s a mix of real if distorted science and wacko cosmology. Some episodes seem simply off the air, smutty, over elaborate but usually arrive at a kind of meaningfulness, as does the seductive rhetorical illogic of a good sermon (which he illustrates at one stage). Jones introduces us to the Newfoundland beef bucket (used to tenderise tough brisket in salt) deployed in an experiment with his three nubile assistants, seen on screen. They fling sand from such a bucket millions of times, looking to form by chance the perfect shape of Newfoundland and Labrador and they get close. But of course God created randomness. What can you do?

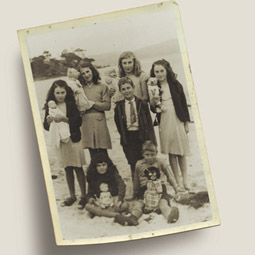

That Newfoundlanders would indulge in such flights of scientific fancy and many other bizarre activities, Jones attributes to the N-factor—a Newfoundland facility for doing things in very odd, lateral and sometimes surprisingly successful ways. This takes us into the country’s history, back to the 18th century, and the Jones’ family’s connection with it, climaxing in the story of his aunt Mary, a Newfoundland beauty who eloped with a protestant English diplomat who was then posted to Berlin in 1939. There it was rumoured Mary, now with an imperious upperclass British accent, snubbed Hitler, so mortifying him that he gave up on invading Great Britain. That’s lateral. The story includes delightful photographs (by Louise Abbott) of a family wedding on a windy Newfoundland day, bridesmaids tottering about the uneven landscape. “No one seems to notice they’re living on a rock!” quips Jones.

If Ken Campbell seems to teeter on the edge of madness in his wilder flights, Jones is on safer ground, for example diverting any extreme nuttiness into the portrayal of a Catholic priest, with Jones asking us stamp our feet when the clergyman has crossed the line into insanity. We’re stamping pretty quickly, but Jones signals that worse is to come.

Like Campbell and Gray, Jones is a deft weaver of tales and ideas, leaving many threads hanging and then ravelling them with bravura sleights of hand. But there are still always surprises to come: “You’re wondering what this show is all about? … Mating!” The cosmological weft is suddenly evolutionary (an earlier thread now picked up) and we’re warped into an hilarious fantasy of genetic tweaking providing the inadequate male with the voice of JFK and bigger buttocks.

There’s plenty to take away with you from To the Wall. Just how many human problems are generated by ‘fitposs’ and what would we be like without it? Why does a confirmed atheist turn to God in moments of extreme crisis? Jones, garbed in a plethora of priestly vestments from different cultures, invites God to join us. He doesn’t turn up, but Jones trips, falls to the stage, and with good Catholic logic, suspects He has been silently present. What are the odds? Other questions linger. How can Catholicism continue to be a creative force when such a punishing one? Above all, is Jones’ account of Newfoundland quirkiness (the N-factor), a condition compounded by Catholicism, true just of his home culture, or is it recognisable, in other ways, in Tasmania or Australia—whose people are so often inclined to insularity, especially now?

Occasional sillinesses aside, To the Wall is amusing and sometimes bracing, performed with affable ease and a self-mockery which fellow islanders from all over will recognise. Best of all, Jones takes the edge off our own troubling fitposs for a while.

Dream Masons

photo Michael Rayner

Dream Masons

For the last month I’ve been walking under a jetty to get my morning coffee. I was oblivious to my underwater journey until Dream Masons exploded over the face of the Salamanca Arts Centre with a spectacular display of mechanical wizardry, bawdy hijinks and vaudeville-style theatre.

Dream Masons was commissioned as a celebration of the Salamanca Arts Centre, a place that has housed and supported Hobart’s creative community for thirty years in a jumble of linked sandstone warehouses. The buildings themselves are the stage for the work which is performed across the vertical surface of three buildings over four storeys. Twenty windows were utilised and the entire facade was fitted with scaffolding, rigging, ladders, a twenty metre long bridge, a boat on a rope, three balconies, a fridge and a toilet. And of course, my jetty.

The windows depict apartments within the building occupied by a mixed bag of tenants. The characters are easily recognised types played out in with vaudevillian overacting, repetition and an abundance of sight gags. We meet the hapless fisherman, the bawdy babe, the strong-man sailor, the henpecked husband, the prissy wife, the weeping spinster who is always washing and a boy in a Superman suit. Living at the top of the building, hoarding ice cubes like currency and screaming through a loud hailer is the cantankerous hunch-backed landlady. Each of these lives is highlighted through the changing focus across the facade as windows are illuminated in turn.

Gibberish aside, there is no dialogue and the plot is deceptively simple. Each of these characters goes about their lives until disaster hits. A great flood—possibly created by evil means—threatens their building and the group help each other to escape to the apartment of the unwelcoming landlord. The weeping spinster makes a dramatic escape across her clothesline to safety, but the boy is lost in the waters and eventually swallowed by a whale as big as the whole building. Saved by his snorkel, the boy spectacularly finds his way out through the whale spout and saves the day by releasing the waters.

The main players are backed by a cast of extras, a large band, giant banners to announce the main episodes of the story, a gospel choir and a busy backstage crew whom I imagine running madly between buildings throughout the work. They fill each window with back projections, creating the rising water and the huge whale which are highlights of the show.

While it is easy to take the show at its cheesy face value, anyone who has ever had anything to do with the Salamanca Arts Centre will know that Dream Masons is like taking the place and turning it inside out so that all the melodrama, personalities, politics, shoddy construction and leaking roofs are all revealed on the outside for one hour of madness. I’ve often thought the place was ripe for a multi-storey sit com, but this show goes ten steps further and I now wonder if the centre was also a hub for the protests against the Lake Pedder flooding which is hinted at as a parallel disaster in the show. I clapped and laughed like a seven year old, but also enjoyed Dream Masons as a regular of the Salamanca strip and I will miss those underwater coffees over the weeks to come.

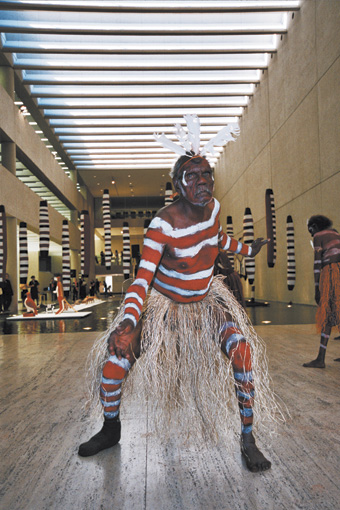

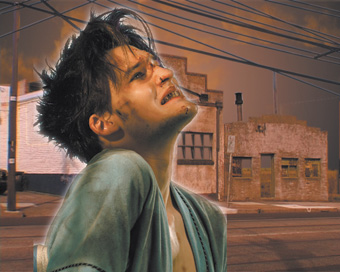

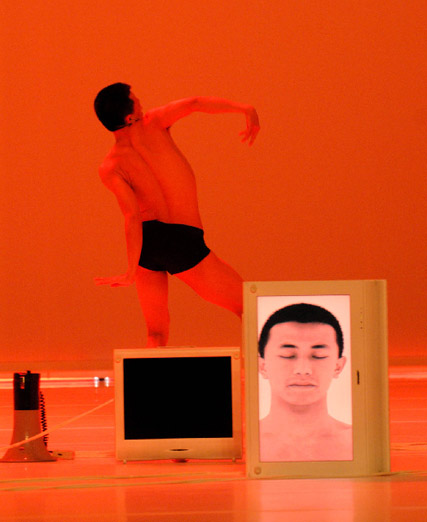

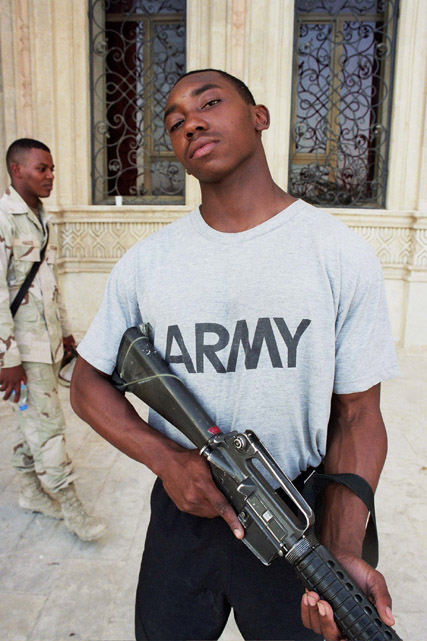

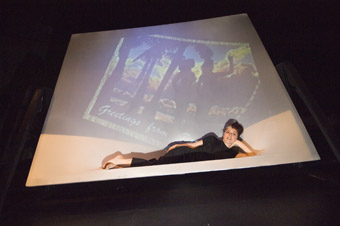

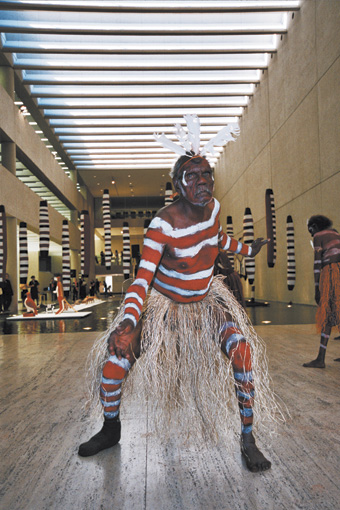

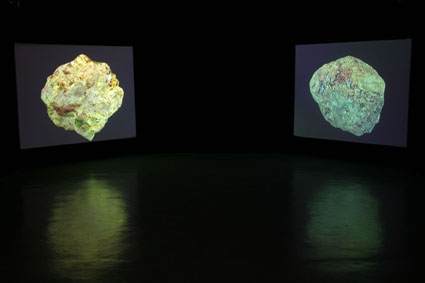

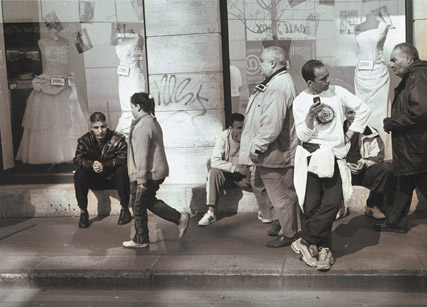

Julie Gough, We Ran/I Am

photo Craig Opie

Julie Gough, We Ran/I Am

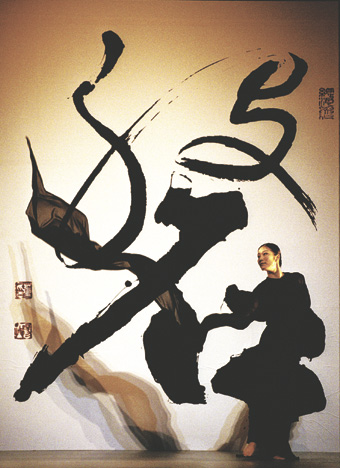

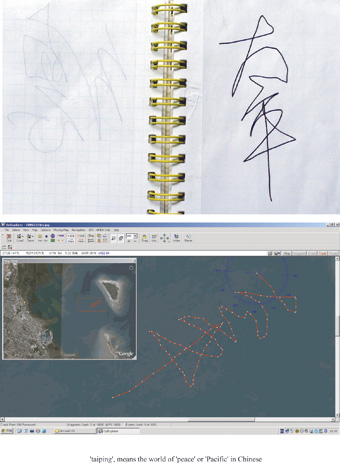

How do we experience place? How much can we ever understand of a foreign place? If we read the signs will they tell us the story? These are questions that arise in experiencing works by Julie Gough and Austin McQuinn in AN OTHER PLACE.

Julie Gough’s work We ran/I am is composed of a series of black and white photographs matched against pairs of rough-sewn wool and calico trousers. The trousers hang as physical evidence of the photographic content. As the artist is documented running through the horizontally mounted images, the trousers underneath bear different levels of soiling that could reflect falls to the ground or lost footing. A map mounted on the side wall shows the marking of the Black Line, part of a notorious campaign in 1830 by Lieutenant Governor George Arthur involving a moving chain of Tasmanian residents intended to round up all Indigenous islanders, most of whom would eventually die as a result of imprisonment and disease. Interspersed between the active images are stills of the tired signposts welcoming travellers to towns along the Line with the standard claims about being “Historic” or “Tidy”. As an adjunct to her title, Gough quotes a journal entry from George Augustus Robinson: “The people all seemed satisfied at their clothes. Trousers is excellent things and confines the legs so they cannot run.” (sic) In similar trousers, Gough relives the escapes of her ancestors.

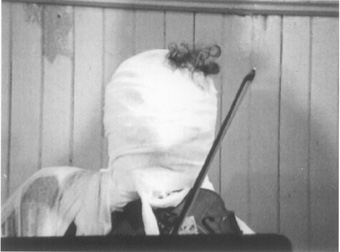

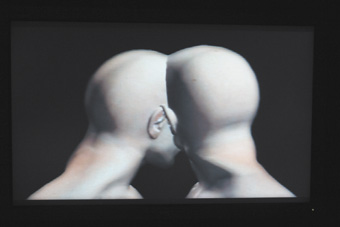

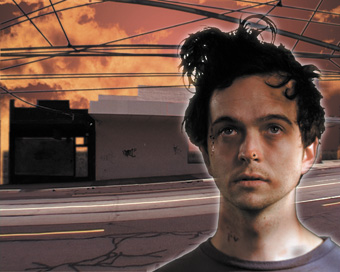

Austin McQuinn, Bogeyman

photo Craig Opie

Austin McQuinn, Bogeyman

Austin McQuinn’s work also journeys through a series of places, but with a different kind of energy. Bogeyman is a wall-sized video projection with a five minute loop showing a series of locked shots of Hobart. Coming into the work at a particular point I was confused by the intent as it flicked through a number of shaky views of Hobart backed with questionable sound. Almost to the end of the fifth shot, my patience waning, his Bogeyman appeared. This creature is presumably the artist or a projection of McQuinn, dressed in sagging black knit pants and top, hands and feet encased in what could be mittens. His head is completely covered by a headdress of knitted toys. The figure is both pathetic and absurd as he walks slowly through each of the shots from the top of Mount Wellington to a single cell within the old Hobart Gaol. In what could be the final shot, he disappears under the bed, like the bogeyman of childhood.

Together these works address a condition that I believe is intimate to Tasmanians and visitors—the sense of experiencing, but perhaps not understanding the place you inhabit. Gough’s work reveals a dark layer of Tasmania’s past that makes a parody of the “historic” in the worn out welcome signs within her images. Her Tasmania is definitely “an other place” from the pristine island that we see in the advertisements and its people are to be feared. McQuinn’s figure also reveals an experience of distance from the landscape. I imagine that his moping monster represents the artist’s feeling of isolation as a resident of Ireland attempting to make work in a foreign place, walking blindly through a landscape he may never understand.

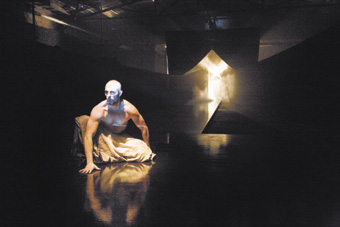

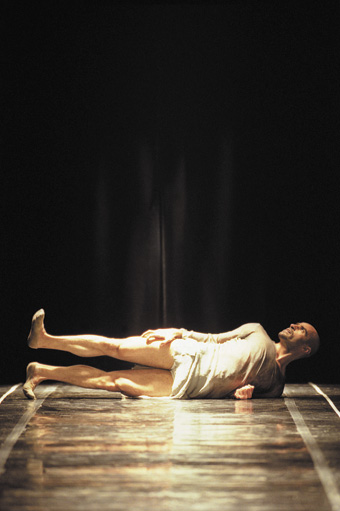

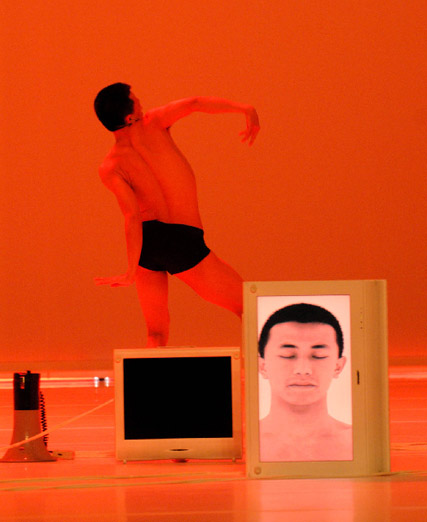

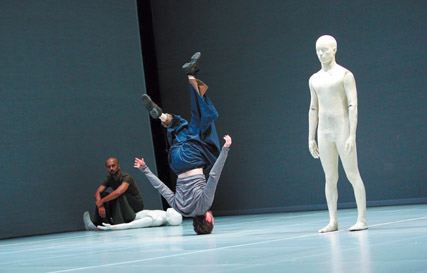

Robert Jarman, The Spectre of the Rose

photo Carolyn Whamond

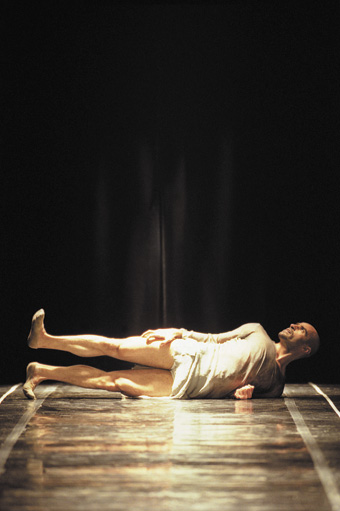

Robert Jarman, The Spectre of the Rose

They called me a thief. I was innocent. They called me a thief, so I decided to be a thief. A false accusation at the age of ten may have been the first defining moment in the chequered life of Jean Genet, French playwright, political spokesman and hero of the Existentialist movement.

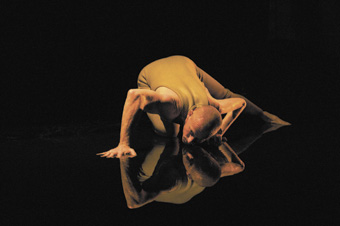

These words are uttered in disgust and defiance by Robert Jarman as he plays Genet in a solo show entitled Spectre of the Rose. The show is staged in Backspace where a small audience is party to the confidences and musings of Genet from prison. His cell is defined by a brick wall at the rear, a sleeping bench, a few personal possessions and a strong white line marked out on the floor. Throughout the work, Jarman remains behind the line, even while leaning his body out emphatically toward the audience.

The show begins uncomfortably. Genet is prone on his bed, placed centrally in the cell. He is clothed in pants and singlet that are thin and holed. Low restless music accompanies his breathing for an indeterminable time and he seems to be struggling with thoughts or nightmares, his body stiff with tension. I sense the spring of a dancer in this man and as if to prove this Jarman’s Genet leaps from his bed and begins his monologue like a ranting madman. He runs around the cell, listens at the wall and is wide eyed as he describes the voices of other prisoners that surround him—some murmured, some screamed, some inaudible. He climbs up high to listen and runs laps around his bed describing the ritual of the discipline yard where men are forced to continually run in a torture that is accompanied by the indignity of defecating in a can in full view of the others.

Once Genet has articulated his dreadful circumstances he quietens and begins to explore his thoughts. It is now that he makes sustained eye contact with audience members and there is a sense that he has decided to trust us. We are his confidante.

Genet’s imagination is rich and dark and perhaps that is how he survived lengthy incarceration. He appears to have the capacity to build relationships with imagined foes and lovers to the point where the heights of experience with those he selects bring him a kind of satisfaction, sexual or otherwise. He shares his heroes with us—they are murderers whose faces he has pasted to a board concealed in his room. He is excited by their crimes. As he says, “The only way to escape horror is to bury yourself in it.”

This portrayal of Genet reveals a complex man. While I believe that we are expected to feel some revulsion at his delight in the worst of human behaviour, Jarman’s Genet is also tender and loving. As he describes his relationship with a fellow prisoner and re-enacts an afternoon of slow dancing in a cell—the only permitted form of affection—the depth of feeling, the love, the grief for this lost love is very moving. To some extent, he is a slave to his own desires and we witness the inability to gain distance from his turmoil culminating in self mutilation. Perhaps this is the inspiration for the trilogy of which this play forms part—Prisoner of Love. Seeing the show is a visceral experience that could be confronting for some as it involves blood, nudity, masturbation and simulated fellatio, but beyond this are moments of lucidity and stunning observations that inspire reflection on the condition of being human in such extremity. Seeing the show is a visceral experience that could be confronting for some as it involves blood, nudity, masturbation and simulated fellatio, but beyond this are moments of lucidity and stunning observations that inspire reflection on what it might mean to be human in such extremity.

Hobart’s City Hall has been transformed into a caravan park. Inside the corral of five crusty old caravans, chairs and picnic rugs face a small stage and a screen. We have each been given an esky filled with surprising gourmet products—confit of scallops, sugar and grapefruit cured ocean trout, and smoked wallaby. Not your standard family picnic fare. But then, there is nothing quite standard about Big hART's Drive In Holiday.

One caravan serves as technical hub and radio station from which the actors keep us informed about what we are eating, what to do and where to go. The other vans house installations representing four Tasmanian coastal townships. The Crayfish Creek van is particularly engaging as every surface including the vinyl seat covers and the internal surfaces of the cupboards, is postered with naïve illustrations by Rebecca Lavis. She has even created a photo album to flick through and decorated blocks and a jigsaw to play with. The Tomahawk van has illustrations by cartoonist Reg Lynch glowing on a lightbox above the sink while Euan McLeoud’s acrylic and oil landscapes adorn the Trial Harbour van. For Southport, Christine Kilter has created a haven for kitsch with crocheted cushions, gaudy figurines and a series of snowdomes with pictures and stories from the area. The vans are intriguing and warrant time to absorb but we are instructed to return to our seats, or picnic blankets to watch the show.

While we sample our exotic edibles a duo sings a sweet and melancholy acoustic number and the “movie” begins to roll. We see a woman, Crystal (played by Kerry Walker) through the window of a caravan. Surprised by the appearance of a police officer, she chokes on a piece of food. There is sharp edit, and we realise that the action is now live, being filmed in the Couta Rocks van to our right. We can choose to watch the live action surrounded by a young crew holding boom, camera and lights, or we can view the action on screen. This is a movie in the making.

Pre-recorded footage offers the unhappy back story of divorce, custody loss, and a sea change. In a live scene in the van a gentle friendship between Crystal and Keg (Lex Marinos) unfolds as she helps him write his will. Back to animations and prepared material and the tale of a freak discovery—a human toe in the guts of a fish. Then we switch back to a repeat of the live scene as a policeman delivers Crystal the message of her ex-husband’s unfortunate demise.

And this is just the beginning. It’s a mini-series and the drama continues to develop, using a connection to Keg as the binding agent and taking in the towns we have experienced via the van installations. We meet a young girl, his niece (Dawn Yates), playing a piano in the middle of the bush at Southport, her mother with Alzheimer’s (Kerry Walker) in Tomahawk and eventually there is a love story in Crayfish Creek (or is it Trial Harbour… I’m a bit lost now).

As with all of Big hArt’s work, Drive In Holiday is made as part of a larger community development project, so in addition to appearances in the fictional material, local people are included in brief documentary segments telling stories and recollecting details about their towns. The fictional scenes that follow illustrate how this is incorporated into the narrative.

The shifts between live and set footage gradually break down, the switching between lines of recorded and live dialogue becoming unwieldy. The actors abandon the filming scenario and simply stand on the stage reading from their scripts. Originally I suspected a technical hitch as Marinos receives instructions from the blue-coated floor manager but, as the actors are directed to play the scene as though it were a soap opera, the mock rehearsal reveals another layer of artifice. Again we are reminded that this a story, and a story in the making.

And the story is not finished. As the show progresses the initially tight hold on the narrative begins to unravel. Some of the imposed details and fragments of stories from the community are not completely woven into the plot but rather just hang there, perhaps waiting for the next episode. Why does Crystal take the name of her deaf and dumb sister? And the rapidly developed lesbian love story seems expedient. In the end we are left with another gentle sweet song and an ambiguous kiss.

The scale, complexity, and the integration of interdisciplinary elements in Drive In Holiday is very impressive, and the environment created is completely immersive. However there are are a few elements that niggle. The overwhelming nostalgia of the content—a golden era of baby boomer Australian kitsch—is curious considering the material was developed with a workshop of young mothers and their children. And within this atmosphere, the gourmet food, although thoroughly enjoyable, might more appropriately be replaced by a sausage sizzle. The material does also seem to thin out, as the work progresses, less integration of live elements and more scattered plot devices. Despite this Drive In Holiday is a unique and thoroughly engaging exploration not only of a slice of Tasmanian culture, but of the potential of hybrid performance and expanded storytelling.

The Little Match Girl

photo Jan Rüsz

The Little Match Girl

A strongly familiar story that deals with the cold and lonely death of an innocent girl might seem to be a strange choice for a piece of children’s theatre, but then again, perhaps discussing such a difficult topic is exactly what we need from theatre. It’s a brave thing to even attempt, so a great delight to experience something that must have been so difficult that achieves as much as Denmark’s Gruppe 38’s production of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl.

Children’s theatre has different concerns from its adult counterpart, and there’s a common assumption that the performance has to be responsible for the emotional wellbeing of the younger audience. Given that both story and outcome, are well known, the nature of this responsibility looms large, and the company’s reaction to this has shaped the nature of this production in quite particular ways. From beginning to end the cast are visible, and they acknowledge the audiences’ presence. The set, and general appearance of the performers has a hint of genteel poverty, which gives the whole thing a clownish, unthreatening quality. The performers use their own names, introduce themselves to the audience, have their roles explained and produce ‘scripts’, which are not scripts in the traditional sense but images. All perfectly elegant and deft deconstructive moments, and indeed there was much of this throughout the performance: a piece of paper being moved about with a long thin stick to create an illusion of wind is eventually grabbed, revealed as a long thin stick and not wind at all. It’s an illusion. It looks amazing but it’s not real. It’s just a story you’re watching: we’re reading it from scripts, using clever theatrical tricks; you can see us using them. It’s all right. It’s fine.

The set, stark and simple, utilizing projection in many ways, had one particular premise that fascinated – the performance took place within a smaller square on the stage, that was clearly defined early on as a dangerous place to be. Performers entered it at their own risk, a little nervous but with brave hearts. They would take whatever risk necessary for their story, unselfishly keeping the audience a little safer still.

It’s not always dangerous in the space however; a simple projection onto a shoulder-high silhouette of a four-storey townhouse is raised from the floor giving the performers a chance to create images of warmth and food and comfort. It’s all done with a small projector, visibly worked by the performers. It’s all an illusion; it’s not real. We are telling a story. This is how we are telling it, using these clever little things that are simple and easy to use. What’s extraordinary is how many of these things there are, and how much is evoked by their clever, economical usage.

I found this work extraordinarily satisfying. It was everything I look for in strong theatre – intelligent, even witty use of theatrical devices that do not overwhelm or cheapen the story and its attendant emotional resonances. The energy that was created, controlled and shared was very involving; I was caught up: charmed by the way the company told stories and moved by the story they told.

Do you know the type of sound which massages the back of your skull? No? Yes? Well… it is my best attempt at quantifying the intensity of sound that Leigh Hobba managed to create in his performance at the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery. I tried to keep my eyes open to the shadows, the video images and the live dancer but it occasionally became necessary to lull in the pulsating sounds of Hobba’s clarinet playing and avoid sensual overload by just closing them.

Leigh Hobba is a performance, sound and video artist who announced this event as a “distillation of 20 years work”: favourite performance pieces dating back to 1976. As one of the younger members of the audience, I had never seen any of these so I had no idea what to expect. In the darkened room, two wide screen television monitors sat on each side of the stage, and on a plinth next to the microphone and music stand, a tiny monitor blinked with static. From behind a black curtain, an elongated shadow of the clarinet spreads across the white wall, the monitor revealing what I finally decide is Hobba's pulsing stomach. He alternates between repetitive, modulating series of notes and the bending of long single notes. The effect is ultimately spine chilling. Combined with the rhythmic tapping of the keys, Hobba’s desperate breathing—due to the pressures of continuous playing and circular breathing—and the ever present shadow provide an almost overwhelmingly sensual introduction to his work.

Hobba’s collaborator, Wendy Morrow, enters the room as the sound ceases. My view of her is blocked so, as with the introduction, I am captivated by her shadow. The quiet that follows Hobba’s work fills with dancing until Hobba returns and reads text, accompanied by images that flash up on the various screens: a young boy acting out a brief movement routine, a baby curled up, the jet trail of a plane and the flags of nations fluttering in the wind with repetitive flag pole clanking.

Later that night, when I am sitting through a different performance, A 1000 Doors, A Thousand Windows, I am struck by similarities in the projections, the use of digital sound distortion and the hypnotic effect created by repetition. Hobba calls his work performance art, and Xenia Hanusiak, the singer and co-creator of A 1000 Doors… calls hers music, but both challenge the traditional boundaries between visual art and music.

Leigh Hobba’s performance created a sensual environment that was almost overwhelmingly magical and evoked a strong emotional response, an experience not dependent on prior knowledge of his work.

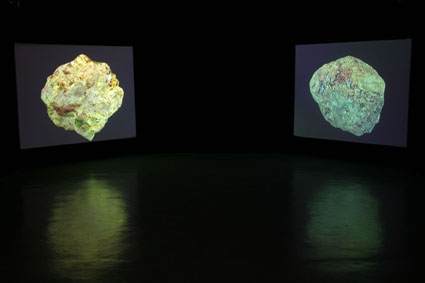

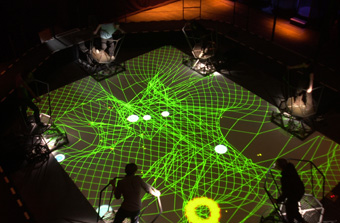

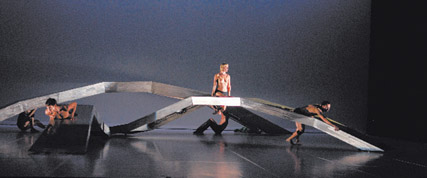

Dream Masons

photo Michael Rayner

Dream Masons

One of Hobart’s beloved landmarks is the stage for a festival extravaganza, one that could not be contained in a theatre or gallery space. Ten Days on the Island wouldn’t feel a complete festival without the outdoor theatre spectacle, Dream Masons.

In Australia, there is a tradition of labelling large-scale outdoor productions ‘community works.’ This often translates to loads of ‘emerging’ community artists working for no money in exchange for ‘training’ from ‘professional’ artists. Dream Masons is not a community work. Expert artists have been sought from the US (co-director Jim Lasko) and the ‘mainland’ (Joey Ruigrok Van Der Werven on design and construction) to work alongside many exceptional local professionals (co-director Jessica Wilson and Tania Bosak, Justus Neumann and Ryk Goddard). Dream Masons has also provided a training opportunity for many budding theatre technicians from the Salamanca Arts Centre’s SPACE course. All of these artists and more and many volunteers have collaborated on the transformation of the Salamanca Arts Centre buildings, making Dream Masons a truly site specific work.

The inhabitants share this liquorice-all-sort of a building and speak in gibberish, howling, laughing and accosting each other as they dance over three levels of the Salamanca Arts Centre façade. Their introduction is perhaps a little uninspired and drawn out but includes some considerable aerial feats. All have white faces with comically exaggerated, doll-like features. A hunchbacked landlady who collects rent in the form of ice cubes, a weeping widow who washes clothes in her own tears, a virile sailor who gets the girl and a confused fisherman are some of the motley crew we meet.

A team of volunteers create vivid underwater scenes with shadow puppets and an amazing whale using old-school overhead projectors. A live band and choir confidently belt out a water-themed repertoire, finishing with Bridge Over Troubled Water.

Large painted banners of popular Tasmanian landscapes are unfurled revealing summations of the action: “The Problem Deepens: a tipped bottle, a never-ending sponge and the sad demise of the overlooked.” They are a little unnecessary and, if anything, tend to confuse rather than add to the story.

The plot however is simple, the premise of the work a kind of cleansing in which a young boy is the catalyst for change and a symbol of hope. As the building and indeed world are flooded he is swallowed into the belly of a gigantic whale to be later ejected from the whale’s blow-hole—depicted by an impressive jet of water shooting out of the arts centre’s roof. With the help of a fisherman suspended high above us in his boat, the boy wields the wheel that will turn a giant tap and purge the building of water. And so he becomes the hero of the story.

Like the characters, the scale of the production is BIG and the big audiences are young, making Dream Masons a refreshing and unique addition to the Ten Day’s festival program

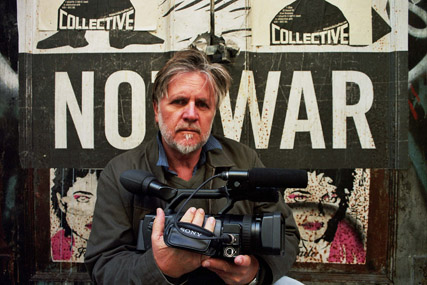

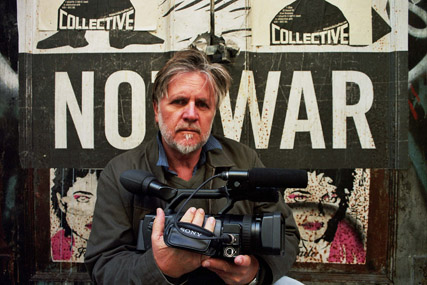

Andy Jones, To the Wall

photo Michael Rayner

Andy Jones, To the Wall

A pulpit and priestly vestments await Andy Jones on the stage. Religion is almost a compulsory subject for comedians today so I am not in the least bit surprised. As the spotlight focuses on the short, stocky and balding man, Jones takes on an evangelical persona and quickly establishes the character of the show.

Describing his Irish Catholic upbringing in Newfoundland, Jones colourfully re-enacts a ‘psychotic’ priest, childhood memories and the odd Newfoundland-Irish character with the help of projections. He calls a meeting in the theatre to which he invites God, suggests new additions to the human body (such as sexually attractive thermostats making visible emotional fluctuations), and uses a Newfoundland beef bucket as a metaphor for the randomness of life and the universe.

The premise of the show is that Stephen Hawking has a theory of the universe, however Jones has a better one. So in a one hour show Jones backs up his evolving theory with evidence. This is hard to follow at times with Jones’ liberal borrowings from scientific language, rabbits, randomness, throwing beef buckets of sand to form perfect maps of Newfoundland and Labrador, and finally the formula “TBP (Teddy Bears Picnic) = x [to the power of u to the power of u]” which supposedly created humans.

Funnily enough, many of his arguments seem logical and convincing, thanks in part to his charismatic personality. In fact, at the end of his psychotic priest impression, when he makes the sign of the cross, he is so convincing that a woman seated in front of me is compelled to follow.

Jones’ theatricalised standup formula is amusing, although at times he

crosses the line into ‘dirty old man’ territory, focusing on projections of female breasts, lusting over the young girls who are his onscreen assistants and making desperate ‘mating’ jokes—especially tiresome after he hands a gift of chocolates to a female audience member willing to confirm his sexism.

Despite these flaws and uninventive use of screen projections, Andy Jones educates a willing audience about the finer points of Newfoundland and its eccentric culture (and the fact that it is built on a rock). He’s convincing as an actor, and the vivid theatrical moments are easily the most amusing parts of his performance. Andy Jones did not make me laugh ‘til I cried, but To the Wall was a unique and entertaining introduction to an island culture on the other side of the earth.

Andy Jones, To the Wall

photo Michael Rayner

Andy Jones, To the Wall

What were you doing when you heard about 9/11? Andy Jones was working on his theory of the universe, and though a self-proclaimed atheist, he prayed to God. And like many of us after these events he was left asking ‘Why?’ What God would allow such a thing to happen? Why are human beings able to inflict, and suffer, pain and misery? Worse still, why are we able to imagine such awful possibilities? These questions lead to his current thesis, delivered in the irreverent and humorous self-devised solo performance To the Wall.

Inspired by the popular writing of Stephen Hawking, this is a journey of amateur philosophy, theology and science. All the big questions get asked, and yet Jones finds many of his answers in the parochial tales from his own family history and their long involvement in the town of St John’s, Newfoundland. His overactive imagination is as ever expanding as the universe itself, seeming to drag everything and anything into his vortex of “N factor” reasoning (Newfoundlanders apparently do everything slightly different from everyone else).

The set is simple yet a little bizarre. There is a desk covered with a piece of crushed velvet, a ‘salt beef’ bucket, an old desktop computer, a wardrobe full of priestly vestments and a gold-detailed podium. Collectively they do not create a setting so much as provide Jones with a selection of props used at various points to elucidate his ramblings. The bucket for example aids Jones’ metaphor for chance: “How many times would you need to throw a salt beef bucket filled with sand to create a perfect image of a map of Newfoundland?” Image projection is used to similar ends with Jones’ wonderful family photographs from the early to mid 20th Century, epitomising the microcosmic dimension of his metaphysical investigations.

The intensity of Jones’ narration played on the anxiety I have experienced when cornered by a talkative boozer at the pub, or when a relative reaches for their photo album. It’s the fear of getting stuck in somebody else’s reality. Jones has studied the techniques of Newfoundland’s Irish Catholic preachers, and the ‘priest gone mad’ strategy has clearly influenced his own performance style. It’s akin to stand-up comedy, even Jones’ appearance—middle-aged man in nondescript black outfit with loud, open shirt—pays homage to this genre.

Jones is very much an entertainer and audience participation is part of his act though no one leaves their seat. Questions were posed to us and I was pulled into hypothetical scenarios, called upon to support his nutty ideas by raising a hand or stamping my feet. I became embroiled in Jones’ world by being made to laugh. To the Wall has many genuinely funny moments, and though it deals with life’s hardest questions this is essentially a light and engaging play.

Apparently, God invented randomness in the Big Bang in the hope of indirectly creating a “lovable equal other.” Jones establishes this role for himself in relation to his audience. Theorising that humour is a biological method of exuding “non-specific attractiveness”, his ridiculous imitation of a bird mating dance doubles as metaphor for the courtship between actor and audience in the theatre. Deviation into sexual innuendo and quips about gender politics however constitute the least interesting moments of this otherwise intelligent show.

Unfortunately the conclusion was abrupt and weak. Jones issues God an invitation to join us in the theatre for a question-and-answer session. He doesn’t come, and in frustration Jones proclaims his atheism. God instantly strikes him down! Or, was it just that he tripped over the keyboard cable? Either way, through the resultant paralysis Jones’ belief in the almighty is renewed and the final scene is a conversation between Hawking and Jones, projected in text and ‘spoken’ through voice synthesisers, where they debate their different theories about the origins of the universe. As Jones himself says, we may be alone but at least we have science. However, all the effort of setting up his theory of the universe over the course of the performance never seemed to pay off. Perhaps, as with science itself, the point is that theories are not always about proving a hypothesis correct—the value lies in the journey of inquiry itself.

The Knitting Room

photo Robyn Carney

The Knitting Room

Agapanthus, geranium and lavender bushes line the white picket fence. Inside the front door is the living room, home to an old dial telephone which sits on a small table with a crocheted tablecloth. A homemade sponge cake is ready for visitors and a turntable (His Masters Voice style) sits poised to play the nearby Elvis record. I could easily be describing my grandmother’s house; but this is The Knitting Room and all of these objects have been knitted, crocheted or woven to make up the exhibition at the Moonah Arts Centre.

The Knitting Room is intriguing for its colourful detail, its historical and cultural value and its surprisingly raw humour. A knitted tyre-swan, iced Vo-Vo’s, Flick bug-spray container, the milk bottles sitting by the door, are all iconic items now disappeared from everyday life. These specific objects of an era now passed, have been created by the over 300 participants in this exhibition whose average age is around 70, with the oldest aged 96. The Knitting Room arouses affectionate memories. The objects are so lovingly made and the room emits this enjoyment.

You enter via the front yard; and from there you are invited to step into the living room, the kitchen, the laundry and then the backyard. The living room is obviously primed for potential visitors, but the kitchen and laundry sit behind-the-scenes for the regular visitor. I feel as if I’m intruding as I observe a knitted woman relaxing in the privacy of the laundry with her feet up, a cigarette close at hand. Adding to this feeling, the rooms are all roped off giving it a distinct museum aura.

Jennie Gorringe, the Arts and Cultural Development Officer for Glenorchy Council, informs me that this exhibition is a collaboration between nursing home residents, community and environmental groups, the CWA, day centres “and artists”, which explains the eclectic mixture of styles, objects, methods of making and materials. I have to question Gorringe’s use of the word ‘artist’ however. Knitting has long been associated with craft, and more specifically with “women’s activity” and consequently, is rarely seen in the context of high art. I am aware of a number of female artists who are trying to subvert this assumption and, observing the skill displayed in The Knitting Room, it’s easy to see why. I believe all the participants in this exhibition should be acknowledged as artists. Labelling the exhibition as a ‘community project’ also somehow undermines the worth of these participants’ efforts. On the technical side, I am greatly in awe of the skill and time that created such a feat. I know from my own disastrous attempts at knitting!

The Centre expects 4000 visitors over the course of the exhibition, and has had a great deal of interstate interest following coverage on ABC TV’s The Collectors and The Arts Show. By the time I arrive at Moonah Arts Centre, the exhibition has been open only half an hour, but 55 people have passed through the doors. This is a true testament to the wide appeal and novelty of this theme, and entirely appropriate for such a moving exhibition.

“Even in an academic context I would never talk about the work of et al, still less ‘explain’ it… the process of viewing art provides the explanation, and it is invariably particular to the viewer. The artist is exactly the wrong person to explain their work…”

This statement by dr p mule (sic) on behalf of the collective, et al. is a telling introduction to the show by this New Zealand group entitled Maintenance of Social Solidarity.

Mounted in CAST Gallery, the oppressive atmosphere of the installation is established immediately by the deep grey walls and ceiling. While the construction of individual objects is rough there’s a strong sense of deliberation and formality to the arrangement of elements within the space. At the entry, I’m confronted with two rows of easels facing each other. I hear a kind of chant bleeding from the other side of the room. Each of the easels displays a poster that has been defaced by cut and paste and packing tape then overlaid with thick, dark, handwriting. This text is like an abstract poem that triggers thoughts about war, solidarity and human rights abuse without really saying anything:

Degrading treatment is

never

Hostility hate

& contempt

day of dooms

a morally

permissible

option

infidel

Hanging from each easel is a set of headphones with soundtrack, the overlaid digitised voices immediately reminiscent of Stephen Hawking. These voices relay excerpts of speeches from key figures in the current war in Iraq, the war in Afghanistan and responses to 9/11. Stripping the actual voice and intonation of the speakers—George W Bush and Osama Bin Laden are featured—places each on the same platform for debate without the prejudice or limitation associated with language or accent. While the idea is interesting, there is a generic quality to the soundtrack –I quickly return the headphones—I feel like I’ve heard it before, another exhibition, other artists.

The remaining elements in the show hang together as one. In the centre of the room a cyclone fence encloses a large projection screen. Twelve chairs sit under a spotlight in their own cell—taped markings on the floor—as if to house a jury or audience at an execution. A desk is lit by a bare bulb like a monitoring station in the midst of the gloom. The chairs and desk also suggest presences that watch and wait. Three more easels sit beside the twelve chairs and on the wall behind them is a grid of images that map mathematical equations, again, defaced by loose, hand written text.

Within the fenceline, the projections are from Google Earth. In digitised tones I hear—“Stockholm”, “Cairo”, “Frankfurt”, “Washington”, “Baghdad.” The projection responds, spinning across the surface of the earth in that familiar Google way before settling just above an airstrip, as if about to land. At first I thought it searched out actual locations, but after a few repeats of the loop, I realised that these were fictionalised places where all else but that which immediately surrounds the airstrip seems blurred, missing or perhaps obliterated. It is as if I am witnessing a series of virtual airstrikes, perhaps from a simulated cockpit. At a certain point in the recording, most notably after “Baghdad” is uttered, the screen freezes and the recording switches to the haunting chant I heard upon entering the space. Given its Middle Easter edge, I read this like a prayer sung prior to attack.

I feel as though I’ve stumbled into a military monitoring or strategy room. From what little I can find about the secretive collective et al., this show is both typical and unique. The consistent aesthetic, the deep grey paint and the elements that appear to be modelled on some militaristic institution are typical. What is not is the minimalism of this piece – the group is known for using a mass of outdated sound and screen technology, quite often to build a cacophonous atmosphere. The use of headphones here allows the sole soundtrack to dominate and the space is easy to read in its arrangement. Given the introduction suggests the work should stand alone, I expected to be able to come to some sort of conclusion about it, but this obtuseness is also typical of et al. While I don’t feel like I’m treading any new ground I am intrigued by this show and the visual imagery—quite beautiful in its own way—stays with me.

Mikelangelo & the Black Sea Gentlemen

photo Matt Newton

Mikelangelo & the Black Sea Gentlemen

The Nightingale of the Adriatic crooned and swooped in the crazy cage of the Crystal Palace last night, christened by the chants of the crowd The Baltic Stallion—they were swiftly corrected by the charming Balkan.

Mikelangelo’s statuesque form, clad in high black pants, danced in the mirrors beneath the chandeliers and disco ball of our devil’s kitchen. His voice soaked in sauerkraut, he truly was the devil sent from heaven. At one point, he enters the room like the Lone Ranger, guitar slung over one shoulder, dances on tabletops, caresses members of the audience, enticing even the most conservative of us into a fleshy sing-along—La, lah, lah, la, la. I left the show with blood thicker than wine racing through my veins, chanting La, lah, lah, la, la through Elizabeth Street Mall.

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen are a quintet—guitar, accordion, double bass, violin and clarinet. Each brings his own unique flavour to the mix—Moldavio recites a poem about his tragic downfall from taxidermy; an accountant who was sold to the circus as a child bellows a mournful song from the bar (“like love, sometimes the sweetest grape is the first to go rotten”); and Guido Libido suspends our disbelief in a fantastic short silent film sequence achieved simply with a screen and strobe light. The Gentlemen howl like dogs, crow like roosters and all openly and willing support their front man’s formidable persona.

Besides dubious Eastern European accents, the threads that bind these men are strong musicianship and a genuine sense of improvisation. Together, they radiate a lust for life. From the moment they enter the stage (and kiss each other on the cheeks three times) to the final encore (“seven hours worth of blood, sweat and tears in our home country but here rolled into three and a half minutes”!) there is a striking sense of humanity, a liveliness that opens up the possibility of even the humble potato becoming sexy.

Nothing is staged, rather it’s lived and shared. To be so genuine is risky but this is precisely what makes them so captivating. They embody a mock Slavic gloom and traverse a landscape in A minor where the sea leaves villages stuck in mud flats, where the weather is always bleak and where “we’re all just skeletons dancing in a sea of flesh”.

Mikelangelo demands attention like a Spanish bullfighter, and he and his Black Sea Gentlemen have written polkas for the 21st century that you won’t see on Eurovision.

All this and sauerkraut…I fear I may have become a groupie.

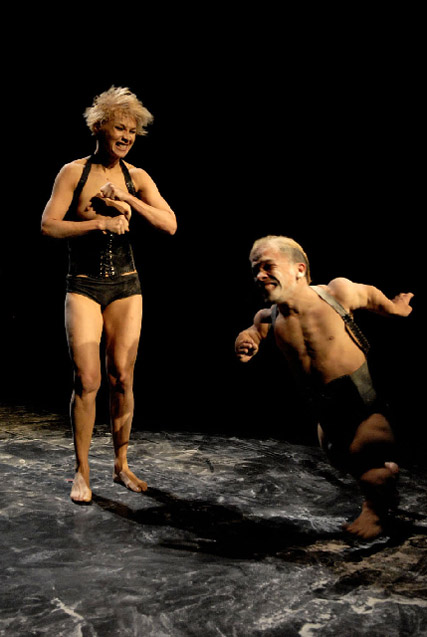

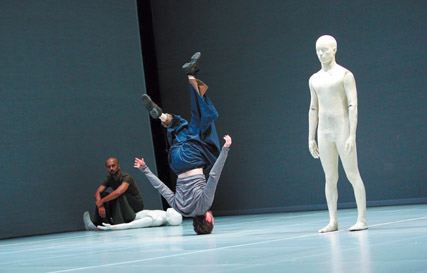

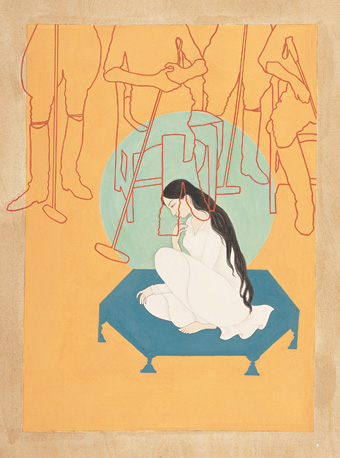

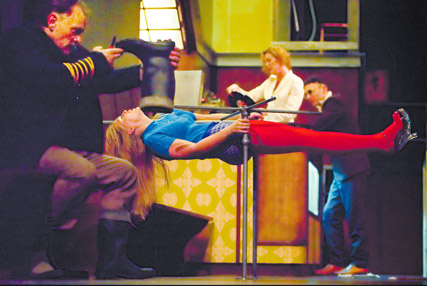

Mercy

photo Michael Rayner

Mercy

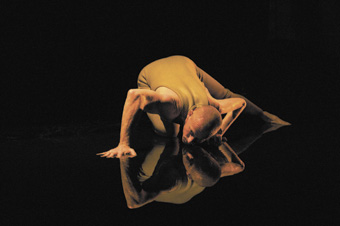

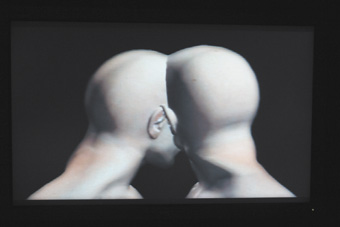

Mercy, the Raewyn Hill-Tasdance collaboration, proved curiously memorable, not the whole production, which problematically aestheticises imprisonment and torture into something quite beautiful (reds and blacks and columns of misty light evocative of fascist chic and movie concentration camps by night), but in a number of individual scenes and a final series that suggest a kind of narrative as an intimate couple go to their deaths.

The whole work, in its choreography, music and design is markedly formal. The brief passages of Pergolesi’s Marian Vespers determine the duration of each scene and evoke, of course, a religious formalism matched in the choreography by gestural imagery of supplication, benediction, crucifixion and pieta-like cradlings. Even their opposites—images of torment and torture—share a Baroque neatness, a dancerliness at times courtly and with evidence too of the balletic underpinnings of much modern dance. It’s when this formalism is broken or a series of images suddenly coalesce into something more potent that Mercy makes its mark in the memory.

A man, stretched out on the floor, wrestles with his chains but what disturbs is a sudden and repeated sharp stiffening of the whole body at the moment he puts his hands behind his back as if to have them bound. One victim struggles desperately in a swathe of red ribbon delicately wrapped about him by his tormentors. Another victim uses her body to plead with her gaoler, wrapping herself around him, climbing and clinging to him, losing grip to fall from his temporary or denied grasp. He catches her exhausted body one more time and she falls, totally and frighteningly limp, face down across his extended arms. He leaves her body behind. Is the gesture he makes one of perverted benediction? Another powerful image is of inert bodies carried in a slow dance across the stage, as if in rigor mortis.

Amanatidis and Dunn stand out in a somewhat uneven ensemble. Daniel Zika’s powerful lighting creates spaces both epic and claustrophobic. Greg Clarke’s costumes include identical bodices and striking skirts for male and female dancers (and the principals share short-cropped hair) creating ambiguity and dark elegance—creatures transcending gender and too beautiful to be destroyed. Unfortunately the balance of the costuming—bare-buttocked, leather strapped—looks the cliched stuff of S&M fantasy, reinforcing a feeling that the content of the work is at the mercy of a sleek aesthetic that undercuts the immediacy of its concerns—fortunately not always.

In a final series of images, Derek Amanatidis dances a remarkable solo of supplication, arms reaching high in a convincing embodiment of prayer, circling low

and returning again and again to stretch up for grace. Amanatidis and Trish Dunn whose bodies have hitherto remained apart but are drawn to one another now entwine in movements of subtle caring such as the gentle cradling of a head. The two separate and lie passively on the stage as a row of torturers advances slowly on them. There is no mercy here, perhaps only in the care they have shared and a dream of grace for those who believe in God’s beneficence—a distant prospect here for all the beauty of the music and the empathy of the choreography. Mercy is at its best when its images of suffering, supplication and caring are at their strongest, when the extremities of torment and yearning are palpable in the dancers’ bodies.

The major retrospective of Leigh Hobba’s work currently at TMAG offered the opportunity for live performance, and the potential was not wasted. Live work has formed an important part of Hobba’s practice since 1996 when he was involved in a number of collaborations at Adelaide’s EAF. This performance was a kind of ‘greatest hits parade’, as Hobba noted when introducing the work and himself. This disarming moment thankfully lightened the tone, which had become tense as an assembled audience of museum patrons and Tasmanian Arts intelligentsia scrambled for the limited seats. This was to be an event.

What then transpired was a gloriously ragged presentation of individual works that moved in and out of each other, creating a serendipitous whole that was strikingly engaging. There certainly appeared to be accidents and human error, but this added an element of informality that freed the work from being a mere rehash of past glories—here was a whole made of parts, like the stark self portraits of Hobba visible elsewhere in this retrospective. Not quite new work, but not a bloodless retread.

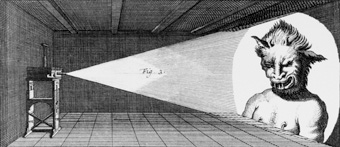

Variations 1, a work from the beginnings of Hobba’s practice was deemed the sensible place to start. Its striking use of shadow and the introduction of circular breathing—a technique of playing long, extended forms without interruption—was immediately arresting. This was ritual. Light and dark playing on the wall, the performer hidden yet totally audible, his disembodied silhouette huge, the image of his clarinet extending out to a vast length, every small movement exaggerated.

Unsure where one piece ended and the next began I gave up trying to decide: yes there was a change of pace here, the mood perceptibly shifted, Hobba spoke of Tasmanian tiger hunters, revealing how spoken text figures in his varied palette. Dancer, Wendy Morrow, a frequent collaborator took the stage and the focus for a time, but the sensation that every moment was an extension of the work prior, a growth out of it, was hard to shake. There was progression in the changes as the onstage monitors blinked awake, almost independent of the actual performers, they seemed to have a life of their own, competing for attention. Screen images were being triggered from assistants in the audience, yet the appearance was random, and the question of technical mishap seemed to hover—was this the intent? What was I seeing? And what was I hearing in the gorgeous trilling arpeggio that ended the piece as Hobba wandered out of the room and into the distance? He seemed elated somehow as he took in the applause, waving his clarinet in a gesture of triumph. Something had been achieved, something with deep significance to the personal world Leigh Hobba investigates.

The curatorial premise is promising. Free Range is an exhibition featuring 28 of Tasmania’s leading designers and their prototypes and one-off pieces of jewellery, furniture, sculpture, lights and ceramics. It claims to provide “…a rare opportunity for the participants to venture outside of the constraints of the designer/client relationship and to try something new or different.” I was hooked by this proposal and excited to find out what results when the creativity and imagination of skilled craftspeople is let loose. My hope was that it might be something truly original, aesthetically challenging, and possibly fabulous.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, given that the show is presented by Design Objects Tasmania, all works are object-based. Nevertheless, there is a contingent of works which range into conceptual or artistic territory. I was drawn to these pieces as they represent the furthest deviation from designers’ usual concern for functionality. Textile artist Grietje van Randen for example creates a very tactile full-scale replica of a potbelly stove. It’s made entirely from felted white merino wool and comments on lifestyle habits exacerbating global warming, and urges us toward sustainable living. Ceramicist Zsolt Faludi contributes Three Islands, a beautiful sculpture of clay, glaze, glass and resin symbolic of the hermetic nature of island culture. Rebecca Coote’s two light objects (the largest sized 100 by 80 centimetres) are tentacle-like architectural installations of glass that wrap around corners and dangle from ledges, while Martin Warren’s intensely coloured slumped glass baskets stretch down from above like cooling toffee. These pieces reflect artisans taking delight in challenging the physical and visual potential of their media, as well their own skill.

Furniture is perhaps the most conservative category of works in this show. A number of unchallenging but nevertheless elegant table, seat and cabinet designs feature the precious indigenous timbers (such as Huon Pine, King Billy Pine and Celery Top Pine) ubiquitous in handcrafted Tasmanian furniture at present.

Patrick Hall’s Typeface is a notable exception. A visually heavy, boxy structure 1.8 metres in height, this piece grapples with recollection through the form of an archival cabinet filled with drawers. The collection—ceramic fragments illustrated with photographic images of faces, labelled with strange catch phrases—are not hidden inside but encased behind glass in the drawer-fronts themselves. This exquisite and conceptually complex object evidences Hall’s statement that his practice “is based in craft, is informed by design, but deals with ‘fine art’ concerns.”

Peter Prassil’s Recreational Device is a reclining lounge chair of aluminium, stainless steel and black leather, gadget-ed with microphone and amplifiers. Stylistically sitting somewhere between a dentist chair and the space age interior designs of the 1960s, this furniture piece also stands out for truly shaking off concerns of practicality and commercial viability in favour of fantasy.

The setting of Mawson’s Waterside Pavilion, a purpose-built design showroom, ensures this exhibition maintains an industrial feel. It could have been interesting to view these pieces in a gallery setting, and a number would certainly have benefited from controlled lighting. Alternatively it would be wonderful to actually sit in Prasil’s chair and find out what the microphone and amplifiers did, or to see Megan Perkins leather belts with luscious enamel buckles modelled.

As it is, these disparate works are collated in Free Range almost like an expo and not quite like an art exhibition and as such fail to capitalise on the opportunities of either format. A picture of avant-garde practice from the creative hybrid zones beyond commercial design is not quite realised overall, yet I sense Kevin Perkins could have addressed this to a degree through stronger curatorial direction. There are undoubtedly many very beautiful objects in Free Range and if I think of the show simply as a loose survey of creativity in contemporary local design, it is an excellent indication of the breadth and vibrancy of the industry here in Tasmania.

The Hobart Chamber Orchestra and Tasmanian Chorale’s concert for Ten Days on the Island lovingly entwined the music of Britain’s Henry Purcell and Ralph Vaughan Williams with works by Tasmania’s Don Kay and Peter Sculthorpe in an engrossing program that for good reason felt more British than Australian. That’s largely because Kay’s Matthina in the Red Dress and Sculthorpe’s My Country Childhood, despite local references, evoke the pastoral tradition of British music (Delius, Bax et al) in the finely modulated long lines of their writing for violins and violas and the darker, often telling underpinnings from cellos and basses. The Kay is inspired by an 1842 portrait by Thomas Bock of a young Aboriginal girl in an elegant dress; the Sculthorpe ‘country’ is in part the Tasmania in which he grew up.

A copy of the Matthina portrait sits to once side of the orchestra in the Town Hall, the girl’s apparent serenity and the quiet directness of her gaze captured in the gentle lyricism of Kay’s composition. There’s nothing programmatic about the score, but there is a gradual if always subtle darkening of mood from the cellos, a few sudden silences, like a dance interrupted, and some later plucking and then firm bowing of the double basses (perhaps a moment of disquiet about what the composer sees in the portrait), ending softly and fading with just the slightest hint of discordance. It’s a work more about the viewer of the painting than its subject—there’s a certain elegiac quality although none of the melancholy of nostalgia.

The Four English Folk Songs by Ralph Vaughan Williams are an acquired taste, but the Tasmanian Chorale under the direction of Stephanie Abercromby acquitted them with ease, attentive to the complex layerings with which Williams embroidered and sometimes laboured such simple songs. Their interest resides in part in juxtaposing them with Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, the first English opera, written some 200 years before the Vaughan Williams and presented in the second part of the concert.

Sculthorpe’s My Country Childhood proved a fine companion piece for the Kay composition, opening in a similar way in part one, Song of the Hills, with a fetching iterated melody and a slight darkening from beneath before a solo violin sings out above the rest. Part two, A Church Gathering, although warmly contrapuntal, evokes a sense of yearning and again the solo violin rises heavenwards. In part three, A Village Funeral, cellos and basses brood, the cello this time dominant in a kind of keening followed by a surge of affecting anguish, heightened by the violins and concluding with diminishing cadences of the same hurt—death now almost accepted. Finally, in Song of the River rapid soft fiddling provides a sense of a speeding current over which run slower waters suggested by a melancholy cello before the whole speeds up in almost frantic ripplings—it’s a wonderful dance of a river as much as a song.

Conductor Myer Fredman paced Dido and Aeneas at the speed it warrants—brisk, allowing the spare drama to unfold without strain and for the listener to feel the considerable force of a string orchestra fattened out with harpsichord, an experience aided by the intimate, clean acoustic of Hobart’s Town Hall. The soloists were all in fine voice, Jane Edwards above all, her Dido heartfelt, unmelodramatic and the continuo playing (cello, Tony Morgan; harpsichord, Stephanie Abercromby) providing firm underpinning for the vocal action. The Tasmanian Chorale were allowed to display their full power and, in the sad final song, their capacity for nuance. This was not a period instrument presentation but the continuo playing and Fredman’s dance-like drive yielded the requisite crispness, elegance and passion.

Entwined was an unusual experience—a traversal of 300 years of music largely out of one tradition, moving broadly from the present to the past, and teasing out kinships between islands—sharing elegance, reflectiveness and a subtle dancerliness in these works. Then again, there was nothing like Sculthorpe’s Sun Music on the program to point to some palpable differences.

We live in a world of make-believe. We access more information than ever before but the technologies that make this possible can also blur our vision of reality. We are under the misconception that information is knowledge. We become insecure and, as we struggle to connect a constructed view of reality with our own lived experiences, ours is no longer a shared reality but a shared ‘dis-reality.’

The strongest point of audience engagement with et al.’s Maintenance of Social Solidarity appears to be in unpacking the theories it presents. The exhibition notes present six introductions to the New Zealand collective which investigates our systems of belief and defines our current state of disconnection. Etal suggests our freedom is at stake when we can no longer choose what we see and hear, perversely distorting our image of the ‘real’ world.

The room is set up like some self-ordering information bunker. The walls are gun-metal blue and a high wire fence encloses a large projected image of the Google map search engine, constantly scanning city to city around the world. As we zoom in on landscapes (bunkers, airstrips and military installations) devoid of any cultural detail, a computer animated voice tells us where we are. This sense of removal is a reccurring theme in the work. Through various technological means (headphones, projectors, laptops etc) we are reminded that ours is a constructed reality that we do not control. Political jargon and religious discourse rather than geography keep us distant from other peoples and lands, generating a sense of us and them and consequent insecurity.

A section of the space is set up with a series of easels to which are pinned large printed posters that have been defaced by a variety of packing and adhesive tapes. Each easel has a set of headphones attached. Some have a mouthpiece so you feel like a scud missile launcher when you put them on. But the mouthpieces don’t work and so the potential of dialogue becomes monologue as computer enhanced male and female voices speak in what first appears to be a familiar media discourse. It soon becomes apparent that the information we hear is mumbo-jumbo. Suddenly I feel angry, as if my time has been wasted listening to a distant rhetoric that pollutes my reality.

At the foot of each easel is a pile of street press style publications which you can take away with you. They are filled with abstracted imagery of sun-spots and quotes from George W Bush, Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein relating to God, freedom and change. Selected words in each quotation have file paths attached, abstracting them and making them seem computer generated.

Sporadic musical chanting is a reminder of our need to connect for more than just information exchange and heightens awareness of our isolation in a room full of technological equipment and computerised voices. Without being culture or gender specific, the Maintenance of Social Solidarity suggests that these notions of isolation and shared dis-reality are everyone’s concern. We are collectively, not individually, to blame for the displacement of our culture. By creating an awareness of how media and political middlemen make meaning for us we become aware of just how distorted our world view may have become. It makes me want to get straight to the source: to have a cup of tea and conversation with someone across the other side of the world and to hear about their reality.

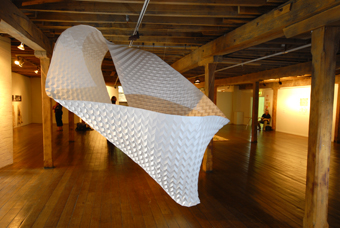

Alex Pentek, Otherness

photo Craig Opie

Alex Pentek, Otherness

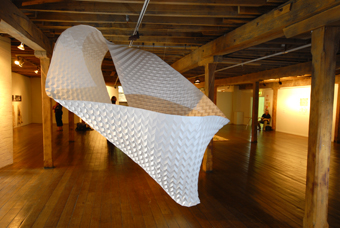

Alex Pentek’s Otherness is a monumental metre-wide Mobius strip constructed from a single length of cartridge paper approximately four metres long. The paper sheet is brought into relief through a meticulous process of scoring and folding. Beginning as a repetition of diamond shapes the folded texture morphs into rounded scales before gradually returning to the original pattern. The loop and twist of the overall structure is simple and graceful.

Amidst the already eclectic range of work in the exhibition An Other Place, Otherness it is an odd entity to encounter. It is big, white and its place within the exhibition concept is at first obtuse. Initially, I complacently assume I understand its investigation: something along the lines of a formalist pursuit of perfection. And I am only vaguely interested.

The sculpture is accessible from all angles and as I wander around its girth peering over its lip into its folds, I begin to realise I’ve been too hasty in judging it. Suspended on wires, it all but fills the volume of space between gallery ceiling and floor. In a dialogue of bodies I warm to this “white elephant” and begin to notice its surprising subtlety.

Natural light passes through the semi-opaque paper, bouncing off and between its surfaces. The interior has the luminescence of a seashell from some angles and elsewhere the gallery’s lighting throws facets of the paper into contrasting yellow and shadow-blue. Disturbances in the air trigger a gentle bounce across the paper structure, a reminder of the material weightlessness of Otherness.

Alex Pentek, Otherness (detail)

photo Craig Opie

Alex Pentek, Otherness (detail)

Crinkles, dents, small tears and holes made accidentally in folding mark the entire surface. No effort has been made to disguise the join in the paper strip, nor the reinforced attachment points of the hanging mechanism. Perhaps the artist was pursuing consistency and perfection, but this work is very much handmade and it bears testament to the fact that the artist is human not machine. The humility of the work renders the concentration, accuracy, care and persistence involved in the Pentek’s labour all the more potent.

An Other Place brings together three Irish and three Australian contemporary artists to explore the notion of ‘other in place’ (felt especially in island places) and curator Sean Kelly in his catalogue essay writes of the slippage between familiarity and confusion associated with this precarious state of being. This concept made tangible in the shifting pattern of Pentek’s work and the eternal loop of the Mobius strip is a powerful metaphor for transition occurring between assimilation and difference within one continuous entity. The play between inside/outside and the twisting that turns both sides of the paper outwards speaks of inversion and extroversion.

Pentek’s sculpture is a floating island: physically self-contained and visually at odds with other works in the show. Its scale makes Otherness impossible to overlook, yet its presence is paradoxically unassuming. What at first appeared a cold rather conceptual and self-referential work turned out, through interaction, to be sensual and receptive.

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen

photo Matt Newton

Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen

Mikelangelo pauses to run a comb through his slicked-back hair “ This song is a rumination on gloom” he announces to the teary eyed audience. That’s right folks; don’t wear your mascara to this one. Mikelangelo and the Black Sea Gentlemen is an hysterically funny gypsy cabaret group playing at the Crystal Palace this week.