Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

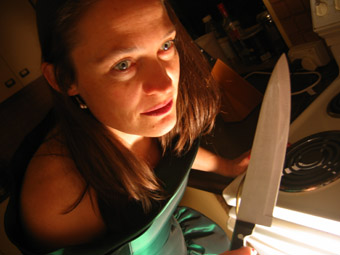

Vladimir's Vladmasters at MadCat

MADCAT WOMEN’S INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL CONSCIOUSLY SETS OUT WITH SAVVY AND INNOVATIVE CURATORIAL PROWESS TO “EXPAND THE TRADITIONALLY ANAESTHETIsED NOTIONS OF WOMEN’S ISSUES AND ATTEMPT TO BURST THROUGH THE CONFINES THAT CAN ENCASE GENRES.”

The curatorial premise then is simple enough—seek out and showcase all the varieties of innovative and challenging film work from around the world that are directed, produced or otherwise created by women.

Transplanted New Yorker Ariella Ben-Dov is the driving force behind the festival. This is the 10th year of MadCat, and founder Ben-Dov never imagined it would evolve into such a major event, with over 1300 submissions, 12 separate programs running over three weeks, and five venues in the San Francisco Bay area.She recognises that audience endurance is a factor and pleads with the crowd to absorb ‘as much as your ass can take.’ The cheering response suggests that she needn’t worry too much.

The creative atmosphere and energy of San Francisco’s experimental film scene is fundamental to MadCat’s durability and positive reception. Long recognised as a global hotspot for avant-garde film (and in American terms, the counterpoint to NYC’s equally vibrant experimental film culture) San Francisco is home to myriad symbiotic film collectives that share audiences, filmmakers, curators, resources and spaces. Some notable examples include established events like Craig Baldwin and Noel Lawrence’s outsider-friendly Other Cinema series, the excellently curated San Francisco Cinematheque, and the incredibly well resourced film programs put together by Pacific Film Archive. And bubbling ebulliently alongside these are underground artist run collectives including New Nothing Cinema, Oddball Cinema and Studio27, which utilise unconventional spaces and draw heavily on expanded cinema and intermedia traditions. Women filmmakers and curators are strongly represented in all of these groups, and MadCat is in the privileged position of being able to draw creatively from this constantly evolving milieu of female film artists toiling away in darkrooms and studios throughout the city.

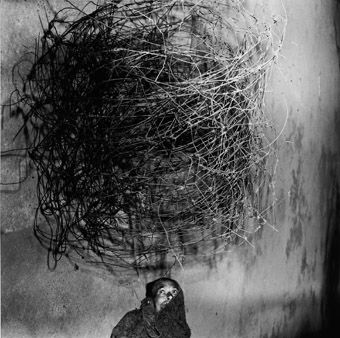

kerry laitala

MadCat’s strong fascination with the medium specificity of film also sets it apart from other women oriented festivals. Indeed, much of the most striking work displays a technical wizardry (or witchery) with hand-manipulated celluloid, optical printing processes and photo-chemical and mechanical treatments. Local film artist Kerry Laitala is a prime example, her work arising from a chaotic, almost alchemical process involving single-frame Bolex constructions which are layered, painted, scaled and radically re-worked through the use of an optical printer. Laitala’s recent films Terra Firma, Orbit and Transfixed were shown across various festival programs. Terra Firma (2005) incorporates an original decaying nitrate print of a 1905 San Francisco film, Trip Down Market Street (shot four days before the 1906 earthquake and fire), and reconceptualises it through direct filmmaking techniques such as hand contact printing and visual explorations of the technologies that punctuate both the history of the city and, more obscurely, the history of film. Orbit (2006) is another work that hinges on the collision of indeterminate technical processes (“mis-registered images made when a lab accidentally split the film from 16mm to Regular 8”) with beautifully captured source material (the pulsating and flickering lights of a spinning ‘gravitron’ funfair ride). Transfixed (2005), augmented by a typically lush David Shea soundtrack, enigmatically blurs between hazy liquid abstractions and a paganistic children’s costume parade, contriving a strangely frightening experience full of handmade effects and trick imagery.

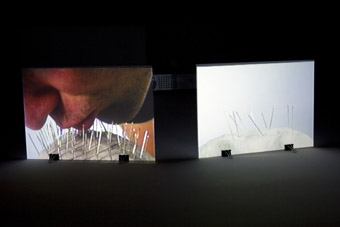

zoe beloff

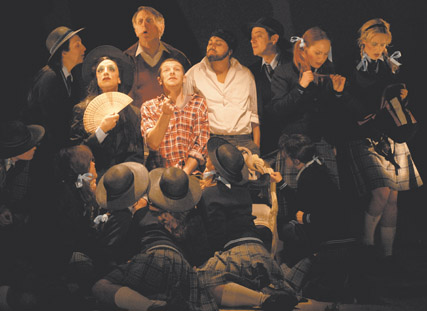

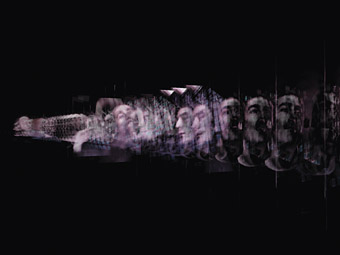

New York film artist Zoe Beloff is a special guest of MadCat 2006, gracing the festival with two programs of her beguiling and obsessional work. Beloff challenges cinematic and pre-cinematic history in a highly idiosyncratic manner, freely re-imagining the technological evolution of moving image media to create an unusual form of pseudo-documentary that is speculative both technically and conceptually. The child of two psychologists, Beloff deals not only with the beginnings of cinema, but the beginnings of psychoanalysis in her films. The two concerns are of course indelibly linked; the ‘phantom’ quality of projected images often struck early film audiences as deeply supernatural, a kind of materialisation or conjuring of objects both there and not there. Cinematic illusionism has always been a perfect form for the representation of unconscious desire.

Beloff heightens the sense of illusion and hallucination with her implementation of 3D techniques. Her work here draws primarily not from 1950s gimmick cinema but rather pre-cinematic spectacles such as phantasmagorias, modified magic lantern devices used to project frightening images such as skeletons, demons, and ghosts onto walls, smoke or semi-transparent screens. Beloff’s 3D is not the familiar red and green anaglyphic system, but a far more sophisticated technique based on the manipulation of polarised light from stereoscopic black and white images that converge and morph as they hit the silver screen.

In Charming Augustine (2005), Beloff speculates through the use of 3D “on what cinema may have been had it been invented a decade earlier.” A fictionalised depiction of Augustine, the iconic young ‘hysteric’ photographed and written about while captive in France’s Salpêtrière Asylum in the 1880s, the film explores the ‘performative’ aspect of hysterical behaviour—a pathology that is ‘acted’ out—and the way in which Augustine’s ‘symptoms’ captivated her doctors with their theatricality and photogenic qualities. We are invited to view Augustine as both mentally disturbed and as a kind of charismatic ‘star’ of the asylum.

Beloff’s Claire and Don in Slumberland (2002) uses real sound recordings of a 1949 psychoanalytic session of a male and female under hypnosis as the narrative basis for a densely constructed mixed-media collage piece utilising 16mm film projectors and coloured stereo slide projections. The manipulative voice of the invisible narrator-psychiatrist prompts and probes the hypnotised Claire and Don, depicted visually as real floating heads attached to ragged doll bodies, their subconscious roaming in a “free floating fever-dream of the Cold War era.” The dialogue is lucid, confessional and somewhat absurd; bodies and voices swap randomly; distant moans, groans and whimpers add to the sense of dislocation. Beloff also treats festival audiences to a selection of early films on psychiatric practices (some acquired fortuitously on eBay and of significant historical importance) and a classic early Betty Boop cartoon featuring a phantasmal creature called “mysterious mouse.” These films help contextualise Beloff’s work and demonstrate the breadth and imagination of her research.

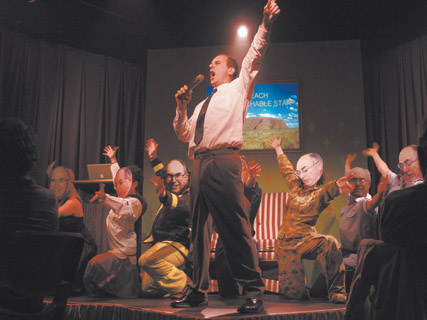

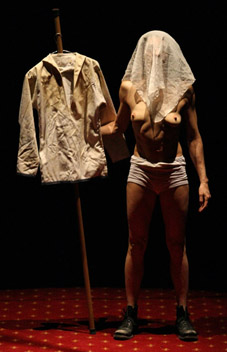

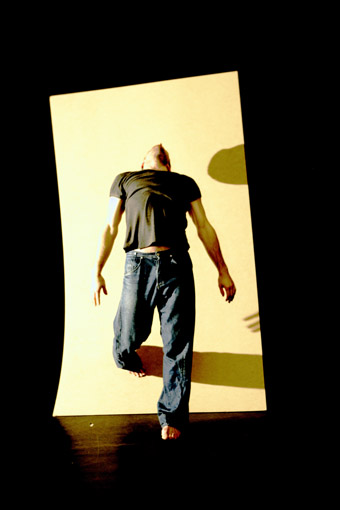

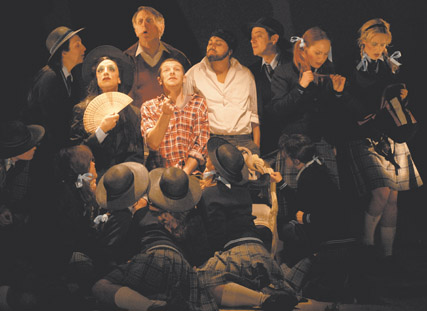

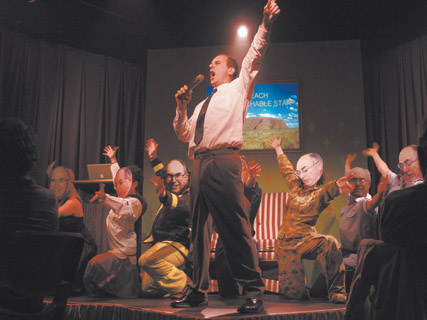

vladimir’s vladmasters

One of MadCat’s most anticipated events is the performance by Vladimir, the Portland based artist who handcrafts her own unique Viewmaster reels, packaging and marketing them in small editions known as Vladmasters. Unless your childhood was cruelly bereft of stimulation you’ll remember the Viewmaster; images are inserted into circular cardboard frames and viewed as 3D projections by holding the plastic viewer up to the light. In 2004, Vladimir was crowned World Champion of Experimental Film by Portland Experimental Film Festival and although that title may be open to some conjecture, there’s little doubt that her work is beautifully formed and hugely enjoyable. Vlad travels with hundreds of Viewmasters and unique reels, enough for each audience member to experience the event in a kind of collective subjectivity. What unifies the experience is the fantastic use of sound, with narration, music and instructional bleeps and dings (for clicking to the next image or changing the reel) keeping the audience in sync and transforming a potentially isolationist technology into something gloriously communal. Indeed, the sound of the enthused crowd clicking their Viewmaster triggers in unison and panic as the pace rapidly increases functions both as a comic and a structural device emphasising the rhythmic playfulness and fluidity of the form. The images themselves construct charming narratives derived from sources including unexplained real-life phenomena, ancient Greek myths and surrealist dinner parties. Vladimir’s work is emblematic of the broad scope of MadCat, where many of the events challenge the way audiences participate and interpret cinema, something of an eternal pre-occupation for avant-garde film.

Over its first decade, MadCat has developed a reputation that stretches far beyond its locality and its program of over 80 films and performances mark it out as an event of international significance. However, as Ariella Ben-Dov accepts and then shares a massive 10th birthday cake with the festival audience, it’s clear that the long-term durability of the festival has its basis in the vitality, camaraderie and imagination of San Francisco’s flourishing film art community.

10th MadCat Women's International Film Festival, San Francisco September 12-27; www.madcatfilmfestival.org; www.othercinema.com/klaitala; www.zoebeloff.com; www.vladmaster.com

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 21

© Sally Golding & Joel Stern; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Still Life

THE SPRAWLING MARQUEE THAT IS THE VANCOUVER INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL (MORE THAN 300 TITLES ARE SPREAD OVER A GENEROUS 15 DAYS) IS SUPPORTED BY THREE MAIN PILLARS: CANADIAN FILMS, DOCUMENTARIES AND EAST ASIAN CINEMA.

These provided two program highlights in this year’s event, one the latest instalment from one of the young masters of contemporary global cinema, and the other a retrospective of one of the medium’s last pure innovators. While China’s Jia Zhangke and Canada’s Norman McLaren could hardly be further apart in aesthetic style, production techniques or thematic preoccupations, both maintain singularly bold visions that successfully resonate widely with discerning international audiences.

east asian cinema

Operating under the banner of Dragons and Tigers, Vancouver’s Asian focus has generated considerable interest for North American critics and local cinephiles. Programmer since its inception in 1992, Tony Rayns’ last ever selection for the festival consisted of the usual heady mix of commercial cinema, underground arthouse projects and cutting edge animation. This eclecticism reflects a healthy film culture that values a diversity of styles across all levels of production. Any program that includes Yiang Liang’s grungy guerilla piece Taking Father Home, Ann Hui’s crowd pleasing, star-studded Post Modern Life of My Aunt, and a stunning anthology of short independent anime from Japan and Korea will be regarded for its breadth rather than for identifying clearly discernable trends. More than just spotlighting the region to Western audiences however, the Dragons and Tigers program can make some claims to launching several notable filmmakers’ careers through its Jury Prize for Young Cinema, which has recognised incipient excellence often well before other festivals and critics. Previous winners include Jia Zhangke (in 1997 for Pickpocket), Wisit Sasanatieng (with the anarchic Tears of the Black Tiger, 2000), Takahashi Izumi (The Soup, One Morning 2004) and Liu Jiayin (Oxhide, 2005, RT67, p22). Jia Zhangke’s latest film, Still Life, appeared in this year’s program (though ineligible for the jury prize), fresh from its much debated winning of the Golden Lion at Venice as the surprise competition entry.

jia zhangke’s still life

Still Life (the actual title in translation is The Good People of the Three Gorges) centres on two parallel stories set in the literally crumbling Fengjie province, primarily in several townships being slowly demolished before flooding by the Three Gorges Dam. A morose, ineffectual middle-aged man is searching for his estranged daughter and ex-wife, while a woman from Shanghai has come looking for her husband, seeking a divorce. The protagonists wander amongst the detritus of the region with an air of quiet desperation, discovering the remnants of a discarded society while they hunt for family members. Villagers cling to their existence, living in houses clearly marked for razing; prostitutes ply their trade in roofless dwellings; and work parties of demolitionists perform life endangering tasks for paltry remuneration. Jia finely balances the mood between mournful and surreal as routine daily exchanges are rendered heroic against the backdrop of the doomed landscape of abandoned towns, meandering rivers and jagged cliff faces.

The opening seconds of Still Life reveal a much grainier High Definition look than Jia’s previous work, there is a more immediate rawness akin to documentary than the cleaner (albeit still digital), sweeping compositions that were the backbone of The World (2004). This is not to say the staging of Still Life is not meticulously crafted; it consists primarily of long takes either tracking over groups of workers or a static frame soaking in the collapsing townships. The length of the shots gives the film a lugubrious pacing that adds, rather than detracts, from its impact as the viewer is invited to explore every facet of the collapsing physical environment and the characters’ internal journeys within it. In an extremely bold manoeuvre, the narratives are framed by two ostentatious magic realist devices (which won’t be revealed here) that further underscore the surprisingly epic nature of the film, rather than jar disconcertingly. As sombre as Still Life can be, it concludes on a cautiously upbeat note, a bravura final shot that becomes a celebration of human capacity for survival, and the film avoids becoming merely an indictment on the bleak social conditions and the emotional malaise of its inhabitants.

Critics of Jia’s work complain that the landscape tends to overshadow his characters, dwarfing them both physically and emotionally, and as a result they seem distant and insignificant in scale; it’s difficult to get too involved in their desires and problems. It is true that again in this film the introspection and underplayed emotions of the characters are in contrast to the louder emotional drum beats on display in more popular cinema, and that their occasional passivity can slow the narrative momentum. However, the time and space given to the performances are refreshing and encourage further reflection and interpretation of action and motivation.

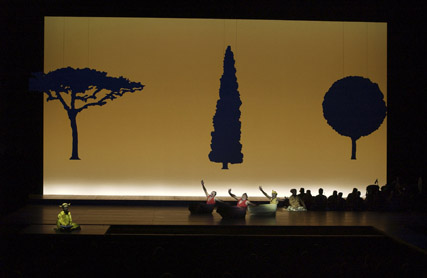

norman mclaren

On watching a wide ranging retrospective of Norman McLaren’s work, it is easy to be impressed with the Scots-Canadian experimental filmmaker’s body of work that combines accessibility with the truly avant-garde. It is a testament to his abilities that McLaren gained a slew of mainstream prizes, in arenas including the Academy Awards and the Cannes, Berlin and Venice Film Festivals when his films rarely contain anything approaching a narrative, and some consist entirely of a swirling, transforming colour palette shifting to a pulsating jazz soundtrack. His films, now well and truly canonised by the Canadians, hold up to scrutiny decades after their production.

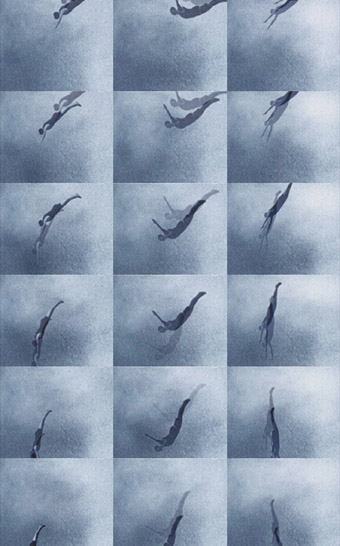

McLaren worked primarily through a self-taught form of animation by painting directly on to film stock or manipulating it through scratches and other indentations. But over a lengthy career spanning through the 1940s to the 1970s, his technique became more varied and deviated from his trademark paint and ink (as in Begone Dull Care, 1949), to playful stop motion with ethical underpinnings (Neighbours, 1952 and A Chairy Tale, 1956) to experimental dance pieces (Pas de Deux, 1968). It is his paint and ink work that is perhaps his most striking, and innovative. His mission to “visualise jazz” is remarkably successful, capturing the free form sound through an ever-changing swirl of colour, bubbling textures and anthropomorphic lines: his sketches dance hypnotically. As digital tools are now the stock and trade of the animator, it is with some nostalgia we view McLaren’s engagement with negatives as a literal canvas, but also with amazement at the end result that possesses at least as much visual dynamism as a contemporary music video. McLaren was not afraid to experiment even further with the stock, scratching the soundtrack of the film to provide startling aural effects. He revels in slight imperfections as much as the clear cut successes, the occasional tangible rough edges often adding to a film’s charm.

McLaren’s visual style is infectious, assisted by a playful sensibility that can’t resist turning to humour. His stop motion pieces are marked by a Keatonesque physical comedy, and his jazz pieces are as naturally upbeat as their accompanying scores, the object being to delight rather than to preach through esoteric posturing, a welcome stance from an experimental filmmaker.

Entering the 1970s, McLaren’s musical interests turned to his own electronic compositions, with some synthetic beats that proved his pioneering skills were not limited to the visual. His animations changed proportionately; the rawer, colourful explosion of the jazz period animations were replaced by cleaner, symmetrical, uniform shapes that march rhythmically to the electronic soundscape, encapsulated in Synchromy (1971).

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) was McLaren’s employer for 40 years, evidently giving him time and space to work on his own projects which he did a prolific rate. The NFB have released a seven-disc box set that comprehensively captures the range of McLaren’s work. His opus is invigorating, an inspiration to continue searching for and celebrating new methods of visual expression.

Whilst lacking the glamour and marketplace components of its eastern cousin in Toronto, the Vancouver Film Festival is focused on bringing quality art cinema to Canadian audiences, and to this end is highly successful. With the continuity of its programming staff and director (Alan Franey has led the festival for almost 20 years) a key factor in its achievements, VIFF acts as a good model for festivals large in scope but wish to keep their focus specialised.

Vancouver International Film Festival, Vancouver, Canada, Sept 28-Oct 13

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 22

© Sandy Cameron; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

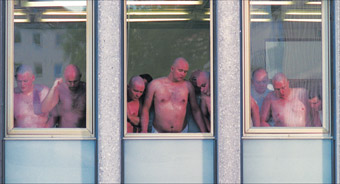

Babylove, Shu Lea Cheang

photo Everett Taasevigen

Babylove, Shu Lea Cheang

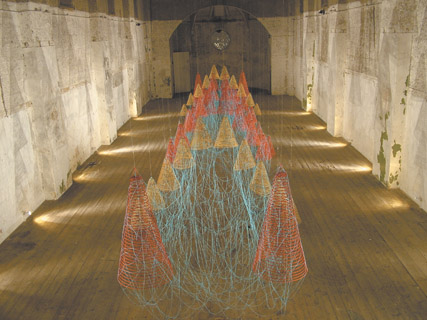

IN 1967, A MERRY BAND OF UTOPIAN POP ARCHITECTS KNOWN AS ARCHIGRAM DEVELOPED A REVOLUTIONARY CONCEPT IN URBAN PLANNING: AN ‘INSTANT CITY’ THAT COULD BE DEPLOYED BY BLIMP TO ANY LOCATION.

With great fanfare and hullabaloo, an unheroic suburb or off-season holiday camp would be transformed into a bustling cultural centre overnight. This concept was articulated in a series of drawings showing the changes that would be wrought on a normal English town following the arrival of the Instant City blimp. From a ‘sleeping town’ a bustling urban centre emerges: buildings spring up and the city is transformed. The instant city embodies the great hopes of modernity, the dream of mobility, of people and infrastructure in motion.

Instant City was included in the Edge Conditions exhibition at the San Jose Museum of Art as part of ZeroOne San Jose, an inaugural major festival, partnered with ISEA2006, of new media and “art on the edge” that landed in the capital of Silicon Valley for 7 days in August 2006. Festival director Steve Deitz cited the Archigram drawings as a point of inspiration for parts of the curatorial concept behind the festival. This was evident in the festival’s spirit as much as its theme: Zero One aimed to “transform San Jose into the North American epicenter for the intersection of art and digital culture.” Instead of helicopters and blimps, it did so through a program that encompassed exhibitions in nearly every local museum and gallery, events in every available venue, screenings, gigs, book launches, street performances and public space projects. In addition, it included ISEA2006, a major conference held in a hall worthy of Ridley Scott, where guest speakers were shown live on large video projections, a running commentary was displayed on large screens and the audience sat on rolling office chairs. And, okay, actually there was a blimp: a small artists’ dirigible called the Fête Mobile that perilously patrolled the breezy streets of San Jose throughout the festival, beaming LED displays and wireless networks as it went.

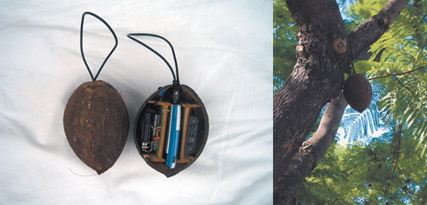

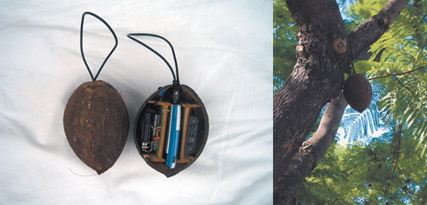

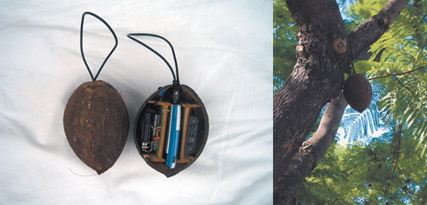

Tripwire, Tad Hirsch

San Jose‘s downtown architecture is notable for being not very tall, but this isn’t because its aspirations aren’t grand. The area is in the flight path to the Norman Y Mineta San Jose International Airport, located just two miles from downtown. As a result, there is a permanent height limit for all buildings. San Jose is a city held in check by its airport: mobility and the city are in conflict. This uneasy relationship with the airport was played out in more than one project at the festival. For the project Tripwire, Tad Hirsch (MIT Media Lab, US) and a team of artistic collaborators installed sensors hidden inside coconuts that were hung in the trees throughout the city. When a low-flying aircraft exceeded a maximum audio level, the system would automatically telephone the airport’s complaint line. The pre-recorded complaints, which can be heard on the project website, appear to reinforce Californian stereotypes. One caller complains that he can’t hear the Steven Hawking book-on-tape on his iPod, and another is totally stoned. Still, Tripwire was an elegant intervention into a very local problem (http://web.media.mit.edu/~tad/htm/tripwire.html).

Another environmental monitoring project took aim at the more general problem of smog, for which the airport can share responsibility with San Jose’s freeway system. PigeonBlog, made by artist Beatriz da Costa (US) and her students Cina Hazegh and Kevin Ponto, employed a flock of carrier pigeons to transport environmental monitoring equipment. Pigeons are filthy animals, and the sheer bloody-mindedness of using them to keep the air clean suggests a kind of poetic justice. But as one conference-goer observed, the pigeons used in the project weren’t dirty at all; they were actually clean and well-mannered, an altogether unfamiliar proposition. Class politics aside, the pigeons of San Jose captured the attention of both local and international media. For once, pigeons had their moment in the spotlight.

Airports were on everyone’s minds at the festival, not just the pigeons’. The Federal Aviation Administration had just announced a ban on any liquids or gels on aircraft, and many conference-goers were subjected to long delays and invasive searches as they made their monsoon-inducing, carbon-belching way to San Jose. Acclair, a project by Luther Thie (Israel) and Eyal Fried (US), tapped into this anxiety with an uncanny sense of timing. The project was a satirical corporation that claimed to offer a service to air travellers: brain fingerprinting, which would collect information from a passenger’s mind before they boarded the aircraft. Some of the information would be used for security clearance, while the rest would be analysed for potential marketing opportunities. The project raised the question of how far a person might surrender their civil liberties to an authority figure, and suggested that the great dream of mobility might come at increasingly high personal costs in the future.

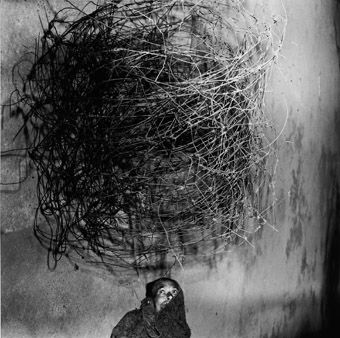

shu lea cheang

Archigram created The Instant City at a time when it was more fashionable to articulate visions of the future before the practicalities had been entirely considered. Many of the projects presented at ZeroOne dealt with the world on a much more logistical level than Archigram was ever able to do: monitoring statistics, intervening into problematic public policy, raising awareness of social and environmental issues. Dealing with the world on this level can be poetic; so much of human experience is encapsulated within small tasks. But in the world of 2006, it takes a remarkable artist to strive to articulate grand visions for the future that aren’t based on criticism and failure, but on potential kinetic energy. Shu Lea Cheang is such an artist. Her installation at San Jose City Hall consisted of a set of teacups, similar to the ride found in many amusement parks, each of which held a large plastic figure of a baby. Visitors to the installation were invited to sit in the teacups along with the baby, steering their way around the foyer space, perhaps colliding gently with other teacups. Each teacup played music that was scrambled and remixed by turning the steering wheel. As with many of Cheang’s works, there was a kind of sci-fi story behind the piece: the babies were clones, the love songs a database of emotional content, and the shared experience of the teacup ride a kind of romantic fantasy. In contrast with prevailing contemporary attitudes and mass media opinion, the piece evoked the possibility of love between human and clone, and elicited the underlying humanity of technology.

not the next new thing

New technologies and visions of the future are so closely linked, they are nearly inextricable. The discussion of the role of new technology in art was a central preoccupation of ZeroOne, as one might expect, and this conversation was articulated through a variety of curatorial stances throughout the festival. The exhibition Edge Conditions, hosted by the San Jose Museum of Art billed itself as being emphatically NOT about ‘the next new thing.’ The introductory text for the show suggested an ambivalent relationship with the field of new media art: “whether it is devices such as pencils and chisels, or ubiquitous aspects of modern life such as electricity, phones, computers and the Internet, technology is simply a set of tools that are more or less familiar at any given time.”

The exhibition offered no shortage of ideas about art in technological times, but these ideas were expressed through a wide variety of media. Ingo Günther’s Worldprocessor may be one of the best examples of this. Between 1988 and 2005, Günther (US) created 300 collage pieces using globes as his source material. Some of the globes are visualisations of data sets, such as television ownership and economic strength relative to land area. Others are more conceptual, such as an image of the earth with every land mass whited out, leaving only the ocean. Like many of the other artists in the Zero One programme, Günther investigates ideas of mobility and the environment, and uses data as raw material, but he does so while still working with physical objects.

Another geography-based project in the exhibition used light as its raw material. Light from Tomorrow by Thomson and Craighead (US) achieved a poetic simplicity despite being awfully complicated to produce. Two weeks before the exhibition opening, the artists travelled to the Kingdom of Tonga, located in a time zone a day ahead of San Jose. They installed a sensor on the island of Nuku’alofa, which transmitted light readings to the exhibition space in California. There, these measurements were translated back into light waves courtesy of a responsive, specially designed light box. A visitor to the exhibition could see the morning light growing in intensity, or the last rays of twilight slipping away—as translated through a sensor, a network, and a light-emitting panel.

In contrast with the thinking behind Edge Conditions, the importance of the tool within art was beautifully articulated in a presentation by Machiko Kusahara (Japan) given as part of the ISEA programme. Kusahara made a presentation based on a paper called “Device Art: A New Concept from Japan.”

It is obvious that the goal of a tea ceremony is not to just enjoy a cup of tea. The importance lies in the whole experience, including the process and the devices used, such as teaspoons and bowls. These tools are functional and made of appropriate materials, and yet there is something more to them than just usefulness. We know that refined tools can make one’s life easier. They also serve as a medium in communicating with others. In a tea ceremony, correctly chosen devices change the whole experience.

Tripwire, Tad Hirsch

This could also be applied to art. It is problematic to separate devices from experiences if the experience is only possible through the use of devices consciously chosen for their purpose.

Kushahara addressed the question of why artists who make games and toys for mass markets could be considered artists, rather than simply product designers; she questioned the distinction between high and low art, an idea which was imported into Japan from the West, and she highlighted the importance of the tool in the creation of artistic experience.

The San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art presented NextNew2006: Art and Technology, an exhibition that likewise placed the digital tool in a central role. The organisers of the show asked five established artists from the region to choose an up-and-coming talent.

The resulting selection was surprisingly coherent, offering a variety of takes on the materiality of digital technology. The centrepiece was Everything Must Go (Grey Market), a floor-based installation by Stephanie Syjuco consisting of paper cut-outs featuring images of e-waste, used and obsolete electronic equipment: calculators, lap tops, mobile phones. Nate Boyce used Jitter and Max MSP to approximate the effects of 1970s video synthesisers, creating psychedelic, pop culture-infused noise videos. Joe McKay’s The Color Game invited two players at a time to use three sliders to match pulsing colour fields projected on the gallery wall. The game was a deconstruction of onscreen colour in the spirit of structural film, asking the viewer to evaluate and isolate the constituent elements that make up a colour display.

Interactive colour fields, telematic light displays, environmental monitoring, digital tools: the ZeroOne programme was wide ranging and diverse. The festival-going experience felt a bit like a walking tour of Alaska, a terrain too large to be properly explored on foot. It was clear, though, that the seeds of a successful biennial festival had been sown. The community was involved, city hall was volunteered as a venue; the programme had institutional and grassroots support, and an international profile. ZeroOne may not have landed from a blimp, but it did succeed in transforming the cultural landscape of San Jose. If ZeroOne didn’t succeed in articulating an optimistic view of technology and society in the future, it did, at least, give us a reason to look forward to August 2008.

ZeroOne San Jose: A Global Festival of Art on the Edge & the 13th International Symposium of Electronic Art (ISEA2006) August 7-13, www.01sj.org

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 23

© Michael Connor; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lian Loke, Kirsten Sadler, prototyping Bystander

photo Toni Robertson

Lian Loke, Kirsten Sadler, prototyping Bystander

ARTISTS HAVE ALWAYS SOUGHT WAYS OF SEEING THE THINGS THEY ARE MAKING THROUGH OTHER EYES. GETTING MORE THAN ONE PERSPECTIVE ON A WORK IS OFTEN AN ESSENTIAL PART OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS. IN THE WORLD OF COMPUTER-BASED INTERACTIVE ART THIS NEED IS INCREASINGLY FOCUSED ON A VERY PARTICULAR KIND OF ARTEFACT: THE PROTOTYPE.

This article is based on interviews with artists and curators involved in prototyping interactive art and a reflection on my own work with Beta_space: a dedicated public prototyping environment.

All artforms have their particular ways of being unfinished: rough cuts, maquettes and works-in-progress. These act as proof of concept and invite feedback. The prototype has been imported into interactive art from its origins in engineering via the interdisciplinary field of interaction design. It refers to an original, functioning model which might be hi or lo-fi, and which might represent component aspects of an art-work or a full mocked-up version. The growing use of prototyping in the field of interactive art reflects the need for artists to learn from design methodologies that deal specifically with the problems of human interaction with complex computer systems.

Lian Loke and Toni Robertson are experts in the fields of software engineering and interaction design. They are also artists with practices in performance art and print-making respectively. In 2004-5 they worked with Ross Gibson and Kate Richards on the design of the interactive art-system Bystander, which included several prototyping sessions involving members of the project team and invited participants.

Toni describes prototyping as part of an iterative process of “bringing into being”, through visualisation:

Prototyping is a way of being able to see and reflect on some aspect of an unmade work as part of its making. It’s a way of seeing things that do not yet exist in order to get them to exist.

Toni points out that many artistic processes are iterative in this way and use “interim representations” to reach their final product. In interactive art, however, these representations are the only way that makers can work with the amorphous and uncontrollable aspect of human use. To create a system that effectively responds to this unpredictable material frequent tests are required to challenge the creators’ assumptions about what people might do, as Lian describes:

In interactive works like Bystander, artists are…experimenting with the way people make meaning and with trying not to direct that…Because of the scale of Bystander there were lots of mockups and evolving prototypes along the way…lots of assumptions got challenged—like how people would behave in the space and react to the material.

The level of involvement of the public in prototyping however is controversial. Kate Richards has a long history of using prototyping as a producer of multimedia projects and in her own creative practice. She prototyped her most recent work, Wayfarer (with Martyn Coutts), to an invited group of colleagues during a Performance Space residency in September. She warns that while prototyping is essential it requires careful use:

What’s important is for artists to ask “what are the appropriate tools [from interaction design] and when to use them?” It can be a problem for artists to be too audience focused. Interactive art has to function, so you’d be crazy not to use these tools…but the tools can’t drive the work. The artist has a vision and they have to create the thing and it’s not going to work for everyone.

How can we use prototyping to open up the creative process and include the audience whilst understanding and avoiding the risks? This question is being addressed in the Beta_space initiative—a partnership between the Powerhouse Museum and the Creativity and Cognition Studios at the University of Technology, Sydney. Beta_space is an experimental exhibition venue in the Powerhouse where artists can develop interactive artworks through feedback and collaboration with an audience.

Involving people in public exhibition settings in the process of prototyping can provide valuable benefits. In terms of technical refinement the demands of public exhibition and public use cannot be recreated in controlled environments. For artists the responses of a diverse audience to a prototype can be incredibly rich and revealing. On the other, hand opening up the creative process takes a lot of courage. It is hard psychologically to leave something ‘unfinished’, open to judgment before it is ready to stand alone. Matthew Connell, Curator of Computing and Mathematics at the Powerhouse, and a driving force behind Beta_space, points out that this can also be uncomfortable for the audience. Showing work-in-progress demystifies the normally closed practice of making and challenges the audience’s notions of how to respond to artworks in a museum as complete expressions of an artist’s intentions.

The first part of the solution to these problems is the way the prototype is presented to the audience. A prototype should not be presented as an ‘unfinished thing’, but as part of an ongoing process of dialogue between artist and audience. The prototype is a way of stimulating and grounding imagination. It offers a tangible, shared experience which can be the basis of discussion. It is important to manage and support dialogue between audience and artist by framing the prototype this way and providing structured opportunities for audiences to contribute to the discussion.

The second part of the solution is in supporting the artists. George Khut experimented with prototyping his work Cardiomorphologies during a Performance Space Residency and at Beta_space. (For a vivid description of the finished work, see Tim Atack’s “Cyborg Dancing”, RT72) Khut describes the experience as “a luxury”, to have the opportunity to “take myself out of my own given point of view and see the work differently.” But for him the question was: “How do you derive meaning from this cacophony of voices?” At Beta_space we concentrate on helping artists to meet the audience half-way by articulating the function of the prototype as a part of a trajectory of developing practice. We work with artists to help them clearly express the experiential objectives they are working towards and their aims for the prototype exhibition.

In the case of Cardiomorphologies, there were two key aspects to the audience experience that Khut was trying to create: firstly a sense of integrated physical and mental engagement with the work and secondly a reflective state in which participants consider correlations between thoughts and specific physiological states. For the prototyping process we established a set of affective aims at the outset which articulated these experiential goals as clearly as possible, such as “sensual and kinaesthetic”, “close fitting”, “explorative/curious” and “enabling.”

During the prototyping sessions, audiences described responses that showed how aspects of the visual and sonic design were generating the visceral experiences Khut was interested in. One of the participants said, “At this point…I’m all engaged by the circles…I think they’re amazing and I was trying to experiment with my own breathing to see how much of the shape I can sustain …I’m trying to create something with my breathing here. It’s a very joyful experience.” On the other hand, collaborative work with audiences in workshop environments showed that some of the more reflective aspects Khut was working towards were not materialising in the work. Unexpectedly we found that the format of the prototyping sessions, in which audiences described their experiences in great detail, either alone or in groups, actually contributed in itself to achieving this “reflective state.” This led to a reassessment of the experiential goals for the work, and also of the means to achieve them.

Seen this way prototyping can be approached as more than just a design tool, but as a form of creative practice. Khut reflects on the impact the process has had on his work:

I am considering how these [processes] might constitute a form of relational or dialogical practice in their own right, developing the idea of the gallery as a place where people can explore and extend their abilities to imagine and relate aspects of their experience and being in interesting ways.

The implications of this approach to public prototyping also reach to the heart of curatorial practice. Prototypes are situated somewhere in the provocative middle-ground between objects and experiences. As museums and galleries make the transition from an object-based to an experienced-based culture, public prototyping can itself be considered as a prototype for a new way of conceptualising their role as cultural institutions. For Matthew Connell Beta_space is itself a test-case, a forerunner of what he describes as “a vision of a new kind of museum space that is all about process, experiment and collaboration.”

Thanks to Matthew Connell, George Khut, Lian Loke, Kate Richards and Toni Robertson for their contributions to this article. If you are interested in showing a prototype in Beta_space please visit www.betaspace.net.au

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 24

© Lizzie Muller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Scotch Egg, Gado! Gado! Gado!

photo Alex Davies

Scotch Egg, Gado! Gado! Gado!

ELECTROFRINGE HAS OUTGROWN THE CHEERFUL AMATEURISHNESS OF ITS ROOTS AND TAKES THE QUOTIDIAN BUSINESS OF FESTIVALS IN ITS STRIDE. THE RUN-OF-THE-MILL BUSINESS OF FESTIVAL, WHICH IS INNOVATIVE AND WELL CURATED EXHIBITIONS AND SHOWS, ARE ALL PRESENT AND CORRECT. MORE CAPTIVATING though ARE THE ODDITIES OF THE MANY-APPENDAGED BEAST.

Because while these events aren’t always successful, neat, or even deliberate, the volume and quality of that bizarre spontaneous insanity is the flesh on the solid Electrofringe bones of conventional festival fare.

It’s a delicate business, the fostering of spontaneity. Hybrid media jam venue Collabrador doesn’t have it this year, not to the same degree as last year’s digital arts debauch of the same name. Unreasonable Adults, however, are doing a solid job over at Gift/Back on Hunter St. Like most things at Electrofringe, if it doesn’t begin in cyberspace, it at least protrudes into it, and I guess that’s the motivation for their inclusion in a new media show. Either that, or their hybrid media nature puts them on the same page of a funding acquittal. Whatever the excuse, they are a stack of frenetic fun, remixing such diverse ingredients as books, videos, ministerial correspondence and chocolate bars from punters into an equally diverse profusion of video snippets, photos and sleep deprivation. In their hands, random items, suggestions and textual snippets from all-comers are the seeds of an ebullient upwelling of things performative. The injunction “make a one-minute musical”, a discarded embroidered red dress, and the SMS poem (or IRC chat log?) ‘she is…’ become possibly the world’s shortest musical to still cram in a toe-tapping tune at one minute and 42 seconds. As such, it’s a marked improvement on the genre of the musical all round, with new media cred to boot.

The Unreasonable Adults’ genius is in the material they coax from their audience. As many media as they are toying with and as dispersed the crowd, the Adults still work the Electrofringe audience with a captivating mix of childishness and wryness. The submissions they elicit in the course of their play are little works of art themselves, and they are preserved on the Unreasonable Adults website: “You have to randomly include numbers one inclusive to 512 into your improvisations in no sequential order. Or sequential if you want more of a challenge.” “When you say the word ‘and’ you have to physicalise a Rodin pose…” Or the items “2 x Multicoloured feather boas; Chimes; a packet of 15 whistles; four leaf clover ‘good luck’; Tetrapak purse with 25 cents and old celery; a piece of coral from Daydream Island.”

Holding the banner for the non-sampling, 100% new material contingent is Spain’s hybrid dance Colectivo Anatomic whose AV dance/musical performance piece RAW is noticeable both for its total absence of any unoriginal or sampled material, and its verbose concatenation of every conceivable funding-ready sounding component of new media art. Custom control interfaces? Tick. Motion tracking eyeball controllers? Tick. Mobile devices? Hybrid media? Custom software? Multichannel live video remixes? Tick. What it lacks, sadly, is coherent vision. It’s not like they are at all unskilled, either. Their custom motion-sensing video projection piece was surely the most tightly integrated, well-rehearsed and smooth motion tracking projection performance I have seen. But it was still two dancers running around without detectable motivation after a projected dot, sandwiched between two other performances, with little coherent justification other than showing off their PDAs.

Back to the world of questionable intellectual property then, where we’re all comfortable. Filastine’s set at the festival was an essay in, among many things, artful appropriation, world cultures of music and industrial zoning chic. From a podium of two shopping carts affixed with auxiliary bullhorns, they mix Cuban, drum and bass and hip hop tracks in at least three languages and play a profusion of percussion instruments, including the shopping carts themselves. It’s a danceable but painfully literate set, crossing smoothly and respectfully between traditional rhythms of South America, the Middle East, India and various schools of music in which I am totally unversed. In terms of source material, if not production techniques, this set is remarkable for the explicit avoidance of the musical hegemony of the West, combining tracks and loops on their own terms. After the somewhat restrained record playing of the prior hour, the crowd explodes. This dreadlock’d gentleman has the advantage of being at one of the moments, if you had to pick two, that climax the festival. The other contender occurs only a few minutes later, an unplanned exploration of collaborative live jam spontaneity: dual-gameboy-and-megaphone gabbacore DJ, Scotch Egg, aka Shigeru Ishihara has taken the stage and incited the crowd into near epileptic convulsions with what afficionados term ‘spastic beats’, and is dancing onstage with a woman in a furry chicken suit. Then Newcastle fixture Peter “Shok” Hore, aka Peter Michael Howard, Serial Pest, crash tackles Shigeru’s precarious bar table of gear, simultaneously invalidating a half dozen warranties and dislodging sundry leads, cartridges and batteries. The most ear crushing silence I have ever heard ensues.

The crew down the stage lights while Hore is bodily ejected from the venue. In the brief window of audibility Filastine has started spruiking his music from an upturned bin by the toilets, and it’s the grimy panic-riddled but desperately fun face of This Is Not Art (TINA) we’ve come to love. I don’t have exact change to buy his latest album… “You can download it with p2p filesharing instead,” he says, “or I’ll throw in my last album for 5 bucks and we can make it a round 20.” Having thus found a model solution to a decade of digital intellectual property conundra and scored me two new CDs in a single act, we are drowned out by the birth cries of Scotch Egg’s rebooting Gameboys. Three minutes later Hore walks back in the other door, which has a different bouncer, and is dancing in the front row to the renewed barrage. Oh yes, we like our intractable madness here.

TiN Radio is the stalwart hold-out of TINA/Electrofringe institutionalised chaos, a kind of grab-bag festival clearing house of podcasts, net streaming and even FM broadcasting. Sandwiched between pine-effect chipboard partitions, behind a sign proclaiming “Newcastle Sight-impaired Radio”, the studios heave with an endless stream of guests through the not-just-metaphorically open doors of the not-quite anechoic space, snuffling and cracking through the not-really-studio-grade mixer. Under-resourced, perpetually late and messier than my bedroom after a housefire, TiN Radio looks like a disaster in waiting, but they reliably produce the goods, particularly in the genre of ‘rawcus.’ The wanton collaboration of The Night Share, for example, is dead on the money. This project is a joint venture between many parties united under the banner of Radio National’s most fearlessly mutating audio project, The Night Air. Although it isn’t quite the debut of their Radio National remixing project, it is the boldest thus far.

The first part of the show, Live Feed’s consensus internet-driven mixing experiment is the most radical in production—a different studio setup with impromptu ill-prepared vox pops, live input, including actual pancake chef, in the studio and production over the net-driven August Black’s browser-based Userradio collaborative software. The product is predominantly smooth and surprisingly subtle, with occasional jarringly repetitive interjections, distinctly close to the typical aesthetic of The Night Air. Which may or may not be an endorsement of The Night Air, depending on your faith in the public. For my part, it makes me exceedingly happy. After half an hour of this, Enter Escape’s more conventionally disco production is a welcome stylistic break, dropping the collaborative impromptu mixing for a solo impromptu bracket, macerating the Radio National back catalogue into a parodic mélange of détourned reportage… The Religion Report, amongst others, is thoroughly raided for funk cliches on the theme of “soul”, and all this is interspersed with the room noise and cheers of a crowd of fellow collaborators in the throes of mixing down their own contributions on this, the final night of the festival. And, of course, it’s all podcast.

Electrofringe, curated by Sumugan Sivanesan, Ben Byrne, Cat Jones; This Is Not Art, Newcastle, Sept 28-Oct 2; http://www.electrofringe.net

Unreasonable Adults, http://unreasonableadults.va.com.au/giftback_newcastle.html

Filastine, http://www.filastine.com/

DJ Scotch Egg, http://www.adaadat.com/artist.php?artist=3

TiN Radio, http://www.tin.org.au/

The Night Share/Electrofringe: live_feed, Sophea Lerner, Andrew Burrell, August Black, Jodi Rose, IONiC, Stephan Wieland, Shannon O’neill, Lloyd Barrett, Lucas Darklord, TiN Radio, http://www.abc.net.au/rn/nightair/stories/2006/1732373.htm

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 25

© Dan MacKinlay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

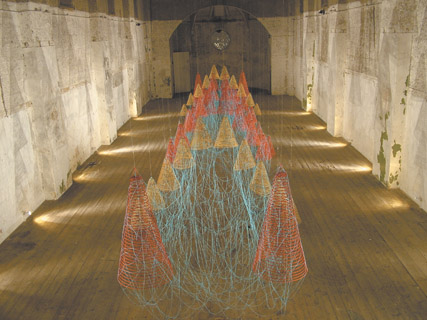

ON A BUSTLING FRIDAY NIGHT IN BRISBANE’S BURGEONING SOUTHBANK PRECINCT, IT WAS HARD TO MISS THE LARGE CROWD GATHERED AROUND WHAT LOOKED LIKE A GLOWING BLUE HIVE-LIKE STRUCTURE, THE [V3] ART+ARCHITECTURE SHOW.

Flanked by the two long, thin canals that run parallel to the Brisbane River and QPAC, the 3D multiscreen installation consisted of five large screens arranged in a hexagon with a space left for entry and perambulation. Projectors were unobtrusive, mounted high on the outside, and though the breeze was fresh that night, the screens, slung between sturdy poles and carefully buttressed, remained resolutely smooth. The steel scaffolding securing the screens with an impressive array of clips and struts, was the first sign that this was no ordinary video art event. As key instigator, Rachel Barnard of the Architectural Practice Academy, noted, “we put a lot of effort into making sure the screens would stay up and withstand the wind.”

Barnard explains how the project came about when she and other architects from yarch.Q, a committee of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, “were talking about films that are architectural and how it would be great to get a cinema to show a series of these…We’d attended a workshop involving a 360 space simulator to view in 3D moving image analysis of space, which we loved, but hadn’t had a chance to explore it further. So we thought, let’s do it. We then came up with a whole series of ideas and 8 months later actually did it!”

The cinematic reference is important, because the second part of the show, in which the works were screened sequentially, after artists’ introductions, felt a lot like a short film program (albeit a multi-screen, outdoors one). The film program effect was offset by the opening and closing events in which spectators saw images of themselves in the space on the night. Rachel explains: “On arrival, there was a delayed live feed playing—in this way the viewers encountered themselves from the past. This process of looking back in time at oneself aimed to titillate but also emphasise the temporal nature of new media art works. Similarly at the end of the night there was a delayed live video feed which showed the construction and the event itself at the end of the night.”

The program of works included video art by local artists and architectural new media presentations. Christina Waterson’s Concealed Revealed is normally hidden in the urban fabric of everyday life. A series of still images interwoven with video pieces, the fast-paced montage of Concealed featured scenes of quotidian reality overlaid with the kind of analytic frameworks and schematic diagrams architects are privy to but of which the rest of us are generally unaware.

A different kind of architectural analysis of the space was evident in Chermside Theatres, by m3Architecture project team Michael Lavery, Ben Vielle and Emma Healy. This featured a 3D ‘fly through’ of the proposed architectural re-design of the site formerly hosting the Dawn Theatre. For an art audience, it was a reminder of the level of sophistication and aesthetic achievement professional animation can attain. Similarly, in architect Ashley Paine’s untitled 1-minute video produced for the exhibition, a complex layering of appearing and disappearing graphic patterns sought to reveal, according to his statement, “new patterns that reinforce the shifting and subjective nature of vision in the original work, while introducing temporality and instability to its construction of visual space.”

On the relationship between art and architecture, Rachel says the affinities are evident, as “they converge both conceptually and actually. After all, both deal with space. [V3] is an example of this convergence. As architects and designers we wanted to explore the relationship between the moving image and space. What happens if a video work ‘expands’, so to speak, to form a spatial experience? We tried to arrange our screens so that people could not only watch a moving work but inhabit a space defined by the moving works. From this we played with ideas of dimensionality, temporality, and the spectator as spectacle.”

Of the work by artists, Gen Staine’s Time Space Frames was ideally suited to the event, especially since one of its most striking images features an alarming series of cracks appearing on the performing arts building (located adjacent to the installation). I found myself wishing again that this beautiful, subtle work, which comments on photography, urban architecture and memory, was longer, especially in the multi-screen mode.

Chris Bennie’s No Faculty Among Us, consisting of a single moving image of a shimmering swimming pool, was also striking in its simplicity. The ethereal effect of the rippling aqua water and serene lane striations was suddenly upset by the appearance of the swimmer, and made strange by our realisation that our view was upside-down. The emphasis was on the revelation of the purely pro-filmic; according to Bennie, “the work aims to render the repetitious and the common as remarkable and extraordinary without embellishment or pretence.” Formally strong and confidently executed, No Faculty Among Us was shorthand for the assured, creative and revealing exploration of space that characterised the whole [V3] night.

[V3] Art+Architecture event, organisers Rachel Barnard, Ye Ng, Jane McGarry for Architecture Week, Queensland Performing Arts Centre forecourt, Southbank, Brisbane, Oct 27

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 26

© Danni Zuvela; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

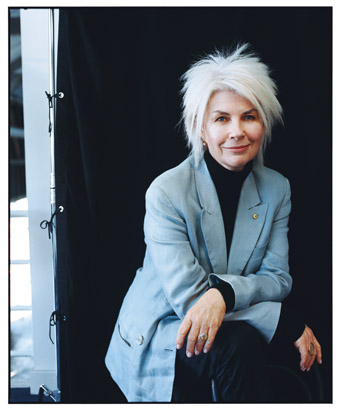

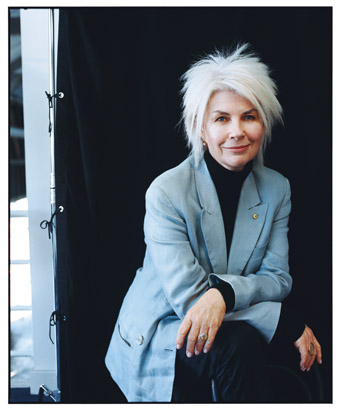

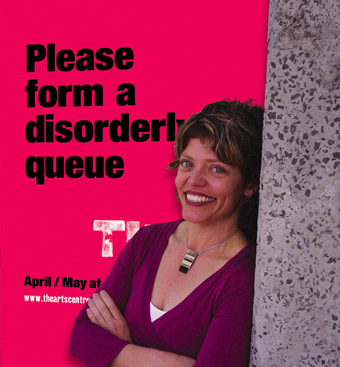

left – Ivy Alvarez, right – J S Harry

Poetry Picture Show

left – Ivy Alvarez, right – J S Harry

THE RED ROOM COMPANY WAS ESTABLISHED IN 2003 WITH THE AIM OF CREATING, PROMOTING AND DISTRIBUTING POETRY TO THE PUBLIC IN NEW AND UNUSUAL WAYS.

Since then it has produced projects such as the innovative Toilet Doors Poetry project in which illustrated poems replaced advertising in the dual public/private space of a number public toilets around Australia, and Poetry Crimes, which used radio and the internet to showcase poems on the theme of crime and justice. In 2006 the first series of The Wordshed, a television show devoted to poetry and writing, was aired on the Sydney community television station, tvs. For The Poetry Picture Show 10 established and emerging poets were commissioned to each write a single poem that engaged with the moving image, to write poems that ‘moved.’ The Red Room Company then made 10 one-minute films inspired by short sections from the poems. The work resulted in a one-off performance of films and poems, augmented later by podcasts, videocasts, a DVD and a continuing blog devoted to discussion of the project.

The night began with JS Harry’s long poem “Journeys Digital—& ‘Other’ Worlds.” Somewhere, around halfway through, these lines reverberated with me:

It is over five months since Saddam’s huge statue

was pulled down — & that act — & scene

turned into photographs,

& recycled, for money,

sometimes with enigmatic US soldiers’ faces

& a few close-ups of excited teenage Iraqi boys, & men,

with stories about the ‘fall’ of Saddam’s regime

on newspaper front pages around the world.

The decision for Harry to read first was a good one as the poem prepared the audience for the complex issues that the dialogue between film and poetry opens up. Harry’s poem dealt with the entanglement of life with the bracken of visual technologies that increasingly construct it, and how this plays out in one of the most watched (and, perhaps not coincidentally, hidden) countries: Iraq. “Isn’t it rather soon for it to be released as a DVD?”, one of the characters asks, articulating a generation’s unique anxiety about the relation of the image to the real. The density of bodies—from the dictator’s statue to real flesh bodies—was continually brought up against the surface of the television and photographic images that represent them.

Other poets took the brief to write poems that move in various ways. John Tranter—whose work, at least since his 1973 collection, Red Movie, has been engaged with cinema and the moving image—contributed a bizarre and hilarious reading of Martin Ritt’s Paris Blues (1961). David Prater did something similar in revisiting the 80s flick Can You Feel Me Dancing?, while Sarah Holland-Batt’s The Limitations of Form was written after Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966). Briohny Doyle’s poem, The Widest Wide Shot, used the conceit of the film pitch to explore the connections between memory and image, while Felicity Plunkett’s The Negative Cutter: An Introduction to Editing borrowed phrases from the technical language of film editing as jumping-off points for poems.

The film inspired by JS Harry’s poem was an abstract piece constructed from various images deployed in the poem: the audience saw a magnifying glass scrolling over a map of Iraq, a huntsman spider, and heard horrific effects that sounded like they were derived from ice cubes being snapped out of a tray. Having just heard Harry’s poem, the audience seemed unsure what to make of this work. Was it a film translation, or an accompaniment? Furthermore, what kind of film, if any, could have taken this poem—already so critically engaged with image-culture—somewhere else? Possibly it was the absence of narrative in Nathan Shepherdson and Sarah Holland-Batt’s poems that encouraged the filmmakers to extend the poems into their own filmic spaces. But apart from these two examples, the filmmakers chose to respond literally to the poems’ images, depicting only their most ‘visual’ aspects.

The films were projected after each poet had finished reading. Guarding the integrity of each poem and film in this way meant there was little opportunity for the artforms and their various elements—spoken language, moving image and soundtrack—to work in combination. There was a sense that this meeting of poetry and film was a bit over-determined: that two forms, always necessarily connected, were being introduced as if for the first time. An imbalance in the organisation of the show became apparent: while the poets were commissioned to produce their work, the films were produced by members of The Red Room Company themselves in collaboration with the poets, meaning there was a similarity of style and approach across the 10 films. Taking on different filmmakers might have brought a fresh approach to each ‘film-poem.’ Other text-image projects from the last few years have worked successfully in this way: the Red Room’s own Toilet Doors Poetry project and the 2002-2003 project Cornerfold (www.cornerfold.com.au), which commissioned artists and designers working in computer media, comic artists, zinemakers and writers to create online animations.

Over the last four years The Red Room Company has expanded the reach of Australian poetry, distributing and broadcasting online, on radio, TV and in public spaces. Its projects have given people who might not have otherwise had a chance to encounter poetry, and to meet it in ways not normally presented. The challenge for the Red Room now is to allow poetry the room to change and evolve as it starts to engage with new media, while keeping those things that poetry already does best: the quiet work of language in a room or on a page. Hopefully the Poetry Picture Show and its online existence has opened up a dialogue in this area that will continue.

Ten of the poems and films from The Poetry Picture Show are available as podcasts, CD, DVD or online at www.redroomorganisation.org and with commentaries in The Poets’ Guide to Picture Shows blog at the same address.

The Red Room Company, The Poetry Picture Show, Old Darlington School, Redfern, Sydney, Oct 6

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 26

© Tim Wright; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Image Lythe Witte (front left) and Property Resistance (back right) lounging with friends at the Oasis Jazz Club

SECOND LIFE IS LEGO FOR ADULTS. RATHER THAN BUILDING MINIATURE HOMES WITH COLOURFUL PLASTIC BRICKS, GROWN-UPS ARE PUTTING THEIR HARD-EARNED CASH INTO TRANSLUSCENT CLAY: PIXELS.

Second Life (SL), if you haven’t already heard, is an online virtual world with over one million registrations. It’s a 3D space that you enter and move around. Unlike massively multiplayer role-playing games like World of Warcraft, Linden Labs (the company behind SL) decided to offer no game, no missions, no tasks or roles to play. It is up to the residents of SL not only to inhabit but create it and everything you can do in it, pixel by pixel. So what do the SL residents, who are on average 32 years of age, choose to create?

everyday avatars

In Hinduism, an avatar refers to the embodiment of an immortal being. In virtual worlds, an avatar refers to the embodied representation of each player or resident. I have an avatar, but cannot claim any access to divine knowledge. And, unlike the imaginative incarnations of Hindu beings, such as Hayagriva’s human body with a horse head, the bodies preferred by SL residents are surprisingly vapid. Most avatars in SL are ‘ideal’ forms such as tall, slim, glamorous women and men with washboard abdominals and even musclier arms. Unlike real life, it is harder to put on weight, age and be ugly in SL. In order to corrupt your avatar you need to either tweak your appearance or buy another. You can look, dress and act any way you like in SL, for a price.

You can choose another gender or species, various personae (Brad Pitt, Yoda), an abstract installation or create your own. Your decisions about how you portray yourself in this world are important because other avatars judge you on those choices. Many residents choose idealised forms for the experience—how it feels and how you are treated. As well as a body, SL residents can buy clothes, hair, hats and nail polish. Everything you try on fits: jeans, dresses, jumpers, tuxedos. These personalisation practices are not unique to SL or virtual worlds, but the facility to be infinitely bold is embedded in the option to program yourself, literally. SL also provides the capacity to weave this construction beyond the avatar to a home and lifestyle.

virtual house and garden

Residents of SL can purchase land and build homes. Rather than suburbia or futuristic hover cars (although they are there), the landscape of SL is a collection of islands that can be tweaked to your heart’s desire. There are tranquil waterfalls, three-storey homes with waterfront views and yachts docked out the front, castles, shopping malls and casinos. Homes can be fitted out with stainless steel kitchen fittings, fireplaces, shag carpets and swimming pools. Residents buy their homes, goods and services from small or large inworld department stores and, wait for it, their favourite designers. Just like real life, there are celebrity fashion and furniture designers and architects in demand. Indeed they often have their own websites and print magazines to advertise and discuss their businesses. Parallel to these SL-specific designers are real world ones that have come in to SL to extend their ‘brand’: residents can buy Adidas sneakers, sip cola out of Coke cans and drive a Pontiac. Why do residents choose to work in a world where they don’t have to?

taking home virtual bread

There are two factors that facilitate this activity: Linden Labs “recognizes Residents’ right to retain full intellectual property protection for the digital content they create in Second Life” (Second Life website) and the inworld currency (Linden Dollars) can be converted to US dollars and deposited into your real life bank account. There are residents, therefore, who earn a living from the money they make in SL. Anshe Chung, for instance, earns over one hundred thousand (real) dollars each year from selling virtual real estate (www.anshechung.com). A resident doesn’t have to run their own business though; they can earn Linden dollars from the services they provide as model, lap dancer, escort, DJ, wedding planner, bouncer, bar person or artist. There are also many real life visual artists, filmmakers, musicians and writers creating inworld representations of their works and streaming live performances.

is SL all work and no play?

Irrespective of the seemingly infinite potential that SL provides as a creative platform, it is a ghost town without the richness of interaction. It is not until people socialise and converse about scientific theories, business practices or relationships that visitors become residents. This shift to seeing oneself as part of a world is facilitated by the cultural and intellectual activity within SL and the ability to communicate more richly. Rather than rely on voice or text, you can run scripts that animate your avatar to laugh, hug and even seduce. Indeed, residents start relationships with varying degrees of real life consequences, get married and have virtual children. However, you can participate in many ways without such intense bonding.

How about dancing and sucking on a cigar at a jazz club or attending an inworld concert with Suzanne Vega or U2? You could also check out The New West, an exhibition of resident—created virtual art which was part of ZeroOne San Jose/ISEA2006 (www.ludica.org.uk/NewWest/). Or, if your inclination is literary, attend Cory Doctorow’s book launch and read his book inworld. If it’s theatre you’re after, see a play at The New Globe or play an elf in a Lord of the Rings simulation. If it’s knowledge you’re after, then attend a lecture streamed in from the Harvard Law School (blogs.law.harvard.edu/ cyberone) or take a class in international new media at Second Lifes’ NMC Campus (www.nmc.org/sl). Or, you could learn about rockets via a live video feed from NASA at the International Space Flight Museum (slispaceflightmuseum.org). If all this ‘high’ culture is a bit too much in a cartoon land, you can always fly over Big Brother in SL and watch fellow avatars throw scripted tantrums over virtual food (www.bigbrothersl.com). Doesn’t this sound like an ideal world?

straw homes

Virtual homes are like houses of straw in that they can be easily blown down by the big bad corporation. When SL is down because of a ‘griefer’ attack or for updates, people are locked out of their second life, their mode of interaction with friends and family, their businesses and classrooms. Sal Humphreys, a post-doctoral Research Fellow from the Queensland University of Technology, has observed the implications for people moving their social lives online to proprietary spaces. So, why do people invest so much time and money in a world that they do not own? Residents do not see themselves as subscribers paying to access Linden Labs’ proprietary world.

Instead, some see themselves as paying LL to manage the world on their behalf. LL is in service to them. This is a paradigm shift in the way ‘users’ are approaching many so-called user-generated sites…a shift that is not shared by the corporations who run these sites. Players, residents and staff persist however. Why?

beyond holodecks

Many online virtual worlds trigger fantasies that the Star Trek holodeck has been realised. A holodeck is that mutable space where the crew of a future spacecraft can summon any scene their imagination conjures. Just like Lego constructions scattered over the loungeroom floor, the holodeck is a space where fantasy takes place. Virtual worlds like SL, however, induce the butterflies-in-the-stomach feeling that a pervasive parallel world is emerging around us. If you can socialise, marry and work in this second life, then isn’t it an equal reality? Irrespective of the intangible nature of the SL world, for many it’s the beginning of a new world and a new species.

Second Life: www.secondlife.com

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 27

© Christy Dena; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

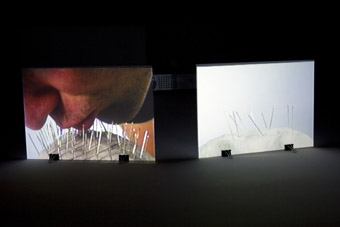

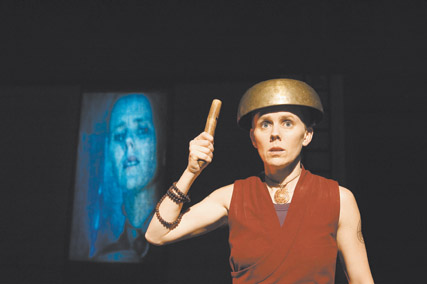

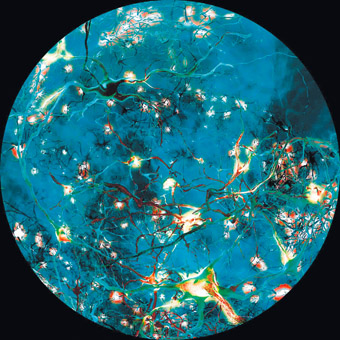

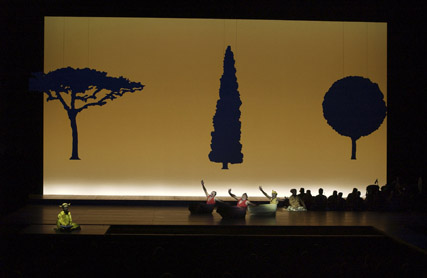

Quartet, Margie Medlin

MARGIE MEDLIN’S QUARTET EXPLORES MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES ON THE MOVEMENTS OF MUSIC AND DANCE THROUGH REAL, VIRTUAL AND MECHANICAL MEDIUMS.

In this second article on Australian/UK-based artists in receipt of prestigious Sciart Awards from the Wellcome Trust in the UK (see Gina Czarnecki, RT 75, p33), RealTime talks to Margie Medlin about her Sciart project.

Medlin is completing the performance stage of research on the project throughout the UK winter with shows scheduled for February 2007 at the Great Hall of St Bartholomew’s Hospital in central London. In this ornate historical setting, Medlin and her team will place a dancer, a musician, a robot camera and two screens, one framing a virtual dancer, the other the point of view of the robot camera.

The idea of using a musician’s gestures to effect a virtual dancer is fascinating—it raises questions of a kinaesthetics of music—what movements produce which sounds which in turn produce new choreographies…? How does it work in Quartet?

A duet between the musician and virtual dancer [created by Holger Deuter] uses both gestural and audio data. Stevie [Wishart] plays the violin, works with her voice and controls 3 virtual instruments based on computational models of human hearing created by Todor Todoroff with the Physiological Lab at Cambridge. Stevie is wired with sensors so that any single action from her can do several things at once—creating sound from any of the 5 instruments, effecting the virtual dancer’s body parts, speed of movement…The virtual body control interface for the project was created by Nick Rothwell.

Is Stevie improvising this performance live?

We are going to have to set a lot of it although she is primarily an improviser and we began with this. We have tried out many of Stevie’s violin playing techniques, such as cross-bowing and plucking, to discover which are the most useful actions in terms of effecting the dancer’s movements and also which have the most intuitive relationships for Stevie as an instrumentalist. Our work together in July and August this year was the first chance we’ve had to connect the two systems as a creative investigation rather than systems testing. The idea is that we make presets or states of sensitivity in the virtual body that Stevie can improvise within. This is very refined work and needs a lot of concentrated effort from Stevie and the team to calibrate her instruments and the interface with the virtual dancer. And at the same time we are looking for visual keys for the audience to understand the connections playing out in real time.

So Stevie is really choreographing the virtual dancer…?

That’s it, or rather her sound and gesture. The other duet is between the live dancer and the motion-controlled robot camera that Gerald Thompson, Glenn Anderson and Scott Ebdon created for the project. The dancer [Carlee Mellow] is wearing three sensors, two 2D sensors, one on her shin and one on her thigh, and a 3D sensor on her chest. The data collected from her sensors becomes the information that runs a motion controlled robot camera.

The robot has three limbs and five motors each operating on an axis and then there’s a small surveillance camera mounted on the robot’s ‘forehead’ capturing its real time point of view. This will be projected during the performance. So the actions of the real dancer are being replicated by the robot and there will be a video projection of the footage shot by the robot camera. This moving image is a representation of the dancer’s movement—from her point of view.

And the data from the real dancer is also going to the virtual dancer, to her left leg and chest. The data from Stevie is going to the virtual dancer’s head, the right leg, the arms the hands and right fingers. Part of the reason we did that is because it’s incredibly difficult for Stevie to meaningfully control the virtual body, to get a sense of connection or flow through the body. In the first stages of Stevie’s connection to the virtual dancer we could only work with ‘close-ups’ on an arm or a leg. We needed to make connectivity through the whole of the virtual body and expand the connection between the dancer and the musician. This is a crucial point because the project is about the transfer of information, how it changes from medium to medium. So the musician and the dancer are controlling different parts of the virtual dancer’s body, but the live dancer’s stuff isn’t programmed at all—it’s responsive.

So the ‘real’ dancer is filling a gap in the information—and is the dancer responding to the musician?

Sometimes yes. There are a number of segments within the performance, for example there’s a duet between Stevie and the real dancer, a duet between Stevie and the virtual dancer, a duet between the real and virtual dancers, a trio between the robot, the virtual dancer and the real dancer etc, building to the quartet.

So the project is about the relationship between the virtual, real and mechanical, but also the observation of those relationships?

An observation and a highlighting of each of those relationships and what happens with the transfer of material, data, intention between them. But also the essence of where that information is coming from—for instance the real people, the musician and the dancer. I’m hoping that the nature of the source of the data will be highlighted as well—what you are drawn to, what’s alluring, what catches and holds attention, where you think the power lies between the virtual, the mechanical and the live elements.

Your interest in the dancer’s point-of-view was apparent in the film you did with Sandra Parker, In the Heart of the Eye. What is it about this particular line of research that keeps you coming back?

It’s about the choreography of cinematic space. There’s been a whole other stage in relation to this research in between, with my three screen work Miss World 2002 which has not been shown in Australia, and it started with Elasticity and Volume [installation, 1998]. When you look at the footage of the dancer’s POV alone, it doesn’t make any sense and can’t hold your interest, its confusing and irritating. As soon as you put the dancer with it, it makes complete sense and is really fulfilling. I’m interested in the relation between that out of control image and the sense of embodiment you get when you put that image in a relationship with the ‘source’ dancer. It’s about the poetics of looking, creating an imagination of looking.

Rebecca Hilton has been the choreographer involved in the first two stages of development. The other choreographers involved in the project are Lisa Nelson (USA), Lea Anderson (UK) and Russell Maliphant (UK). What will they each contribute?

Rebecca made some of the material that Carlee will develop for the performance—a set of alphabetic building blocks—but Lea, Russell and Lisa haven’t been involved at all yet. They’ll come to the rehearsal and each have 10 days. I have asked Russell to work with Carlee on the dancer’s solo and to work with Stevie on the gestures and sounds that she makes and how that impacts on the virtual dancer or vice versa. I’ll ask Lea to work with Carlee and the robot camera and I’ll ask Lisa to work with Stevie and Carlee on the improvisational relationship between the two ‘real’ elements.

They are all very different choreographers in terms of style. Will that complicate things?

I think it’s all very complicated. Having different artists exploring these complicated systems gives an expanded idea of what is possible. I am interested to see how people can use these systems. They will not be given any time to make technical developments but will be asked what they can get from the systems we have developed.

Quartet will be presented at The Great Hall, St Bartholomew's Hospital, London, February 14-18, 2007. Quartet has been funded by Sciart Production Awards 2005-6 in collaboration with the Physiological Laboratory at Cambridge University and the Arts Council of England. It is co-produced by the Performance and Digital Media Department at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, with support from the Australia Council for the Arts, Arts Victoria, and ZKM Center for Art and Technology, Germany. www.quartetproject.net

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 28

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

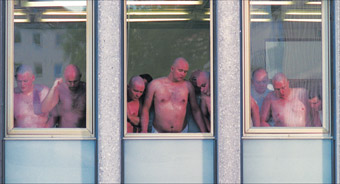

Lisa Griffiths, Isabella Trigatti, Amanda Phillips, Crush

photo Sam Oster

Lisa Griffiths, Isabella Trigatti, Amanda Phillips, Crush

ADELAIDE’S AMANDA PHILLIPS AND MELBOURNE’S FRANCES D’ATH HAVE UNITED TO CHOREOGRAPH A POWERFUL AND AT TIMES GRUELLINGLY INTENSE NEW WORK, CRUSH, AS PART OF I HEAR MOTION, A NEW PLATFORM FOR PROGRESSIVE DANCE ARTISTS PRESENTED BY THE CITY OF TEA TREE GULLY’S GOLDEN GROVE ARTS CENTRE.