Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Chico MacMurtrie, Inflatable Bodie

photo Duke Albada

Chico MacMurtrie, Inflatable Bodie

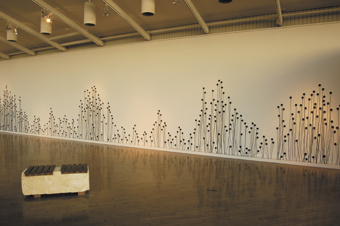

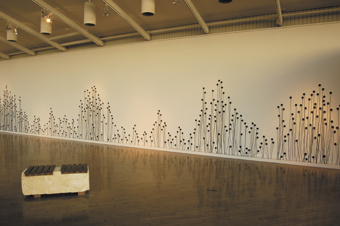

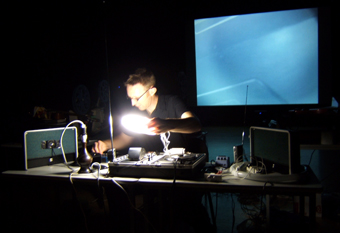

Chico MacMurtrie’s Inflatable Bodies is the latest in a series of works that explore the possibilities of robotics in art. For the Experiemental Art Foundation’s Adelaide Festival of Arts exhibition, MacMurtrie constructed a series of forms resembling birds in flight. Each ‘bird’ comprises 2 thin cones, symbolising wings, with a total span of about 4 metres, suspended near shoulder height from the gallery ceiling. The birds ‘flap’ slowly, suggesting a flock of pelicans moving in single file following a curving line that is intended, MacMurtie says, to evoke the meandering Murray River. The cones are made of heavy fabric, like sail cloth, joined in pairs at a central pivot. A system of air-pressurised bladders inside the cones actuates the pivoting to induce flapping motions, the inflation and deflation of the bladders mimicking the contraction and relaxation of muscles.

The cones are also mechanically inflated, but at periodic intervals the air supply is reduced so that they slowly collapse and droop towards the floor, whereupon the stationary flock comes to resemble a gigantic, disjointed centipede. A computer program controls the flapping and the 20 minute cycle of collapse and regeneration. The movements of each ‘bird’ are slightly asynchronous, imparting a degree of individuality to each specimen. The gallery lights are dimmed so that the birds are illuminated by 14 small spotlights on the floor beneath them, their shadows cast on the ceiling rather than the ground. I sat on the floor of the otherwise empty gallery watching the slow flapping and the gradual collapse and reinflation of the white forms, accompanied by the susurrations of the air pumps, meditating on the vulnerability of wildlife and on how art might imitate nature given the complexity and genius of biological design.

In the days preceding the exhibition, MacMurtrie held a workshop at the EAF. The participants assisted in the realisation of Inflatable Bodies and also conducted their own experiments with robotic technologies. MacMurtrie is the founder and Artistic Director of Amorphic Robot Works (ARW), a New York-based collective of artists and engineers established in 1992. ARW’s central idea is to develop robotic forms that mimic or reflect human, animal or plant forms and movement. For example, an earlier ARW work, Growing Rain Tree (installed at the Contemporary Arts Center UnMuseum, Cincinnati, 2003) is a robotic tree that moves its limbs and rains water that is drawn up from the pool in which it sits. Like many ARW works, it is interactive in that the approach of viewers triggers action. MacMurtrie has also made robots that not only respond to the viewer presence but also mimic their movement, creating a metaphor for human interaction (www.amorphicrobotworks.org).

But why is this an exhibition of art more than of engineering? MacMurtrie notes that robotics is more commonly associated with high-tech industrial development where the emphasis is on the refinement and control of manufacturing processes. Here, the robotic forms are instead intended for contemplation—he describes them as analogues of observed behaviour, emphasising the desire to understand the movement of the body and the significance of that movement rather than the use of technology for technology’s sake. The work’s engineering and computer programming are not immediately noticeable, perhaps prompting the viewer to think as much about what it symbolises as how it functions.

Inflatable Bodies thus recalls Da Vinci’s drawings of human and avian anatomy and his flying machine designs, Renaissance ideas that preceded a period of intense scientific development in the West. MacMurtrie’s work contrasts with the nightmare of Frankenstein’s monster and the inhuman creations of the 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars, Terminator and Blade Runner movies. In the Adelaide Festival MacMurtrie’s peaceful work also contrasted with the dramatic use of robotic prostheses in Australian Dance Theatre’s apocalyptic Devolution (see p 32 and RT 71, p 2). We recall Isaac Asimov’s 3 laws of robotics—especially that robots must do what they’re told but never harm a human. Robots can mimic physical action and basic deductive and computational processes, but we may not be far from the mimicry of emotional states and the integration of these with decision-making and action at large. Art’s crucial role in examining the forms and implications of technological change has been central to recent EAF programming. Robotic art has the potential to examine human behaviours, attitudes and desires from an advanced technological perspective.

The cyclic movements and the expanding and collapsing forms in Inflatable Bodies induce a degree of melancholia if viewed for an extended period. I almost wanted to stand and flap my arms in sympathy.

Chico MacMurtie, Robotic Arts, Inflatable Aestheticism; Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide Festival, Feb 24-April 8

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 27

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Super Vision

Experiencing the retrograde nature of human-to-technology interfaces is perhaps the condition of our time. That’s right; forget ‘the postmodern condition’ (so 70s!). We have now arrived at ‘the condition of interface anxiety.’ Hands up those few who can’t relate to this new condition. The frustration that your pronunciation is rejected by the voice recognition software when you ring ‘information’ for a telephone number; the sudden self-doubt when you’re picked at the airport for one of those ‘random explosives trace scans’ (as if suddenly you can’t be sure that you weren’t handling guns/bombs just this morning); the uncertainty when verisign.com fails to process your payment for that journal subscription. Often we never actually find out ‘what was wrong’ but are left to wonder indefinitely: was it my cookie settings, my web browser, my accent, my account balance, or did I just look suspicious? Certainly the time is ripe for creative works which can make these invisible experiences dance before our eyes. This is what Super Vision attempts to do.

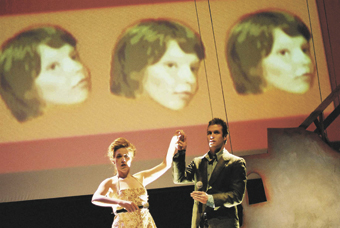

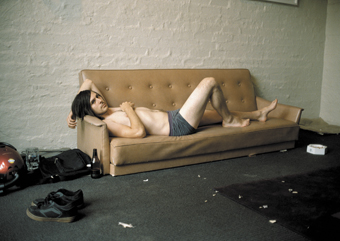

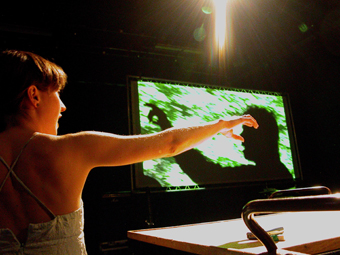

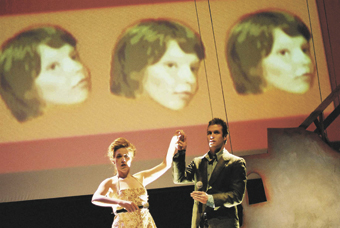

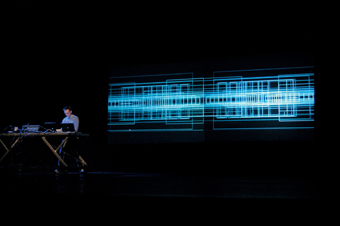

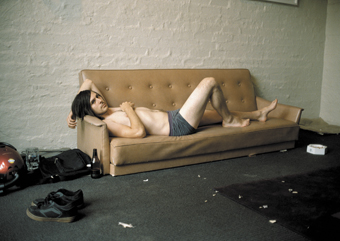

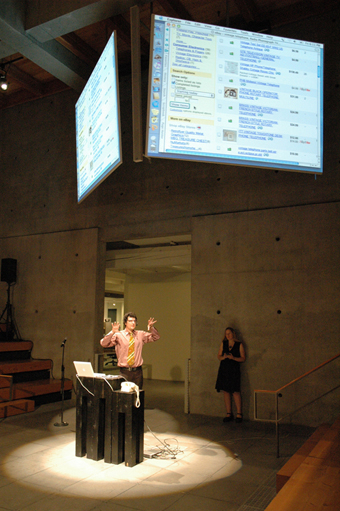

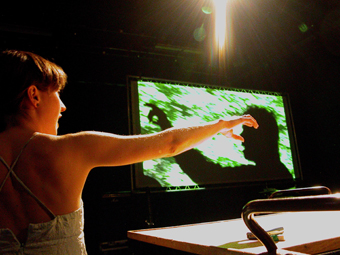

Super Vision is the 9th and latest production of The Builders Association, an 11 year old performance and new media production company based in New York. The company integrates stage performances with video, sound and architectural elements. Here a desktop fills the width of the stage with computer screens and chairs spaced along it. About a metre above, another performance level is housed within a rectangular, round-edged frame. Behind is a projection surface with smaller mobile screens around the frame.

The performers sometimes appear as just another layer of the surface, at other times they are revealed to the audience against the background projections. These conjure loungeroom settings, landscapes, moving text and graphic images, depending on the needs of the narrative. At times the audience simultaneously sees a performer interacting with a computer screen on stage and a large-scale projection of the performer’s face captured web-cam style. The stage becomes a space where human presence, data and representation merge. This encapsulates something of my daily reality where those binaries of real/virtual and original/reproduction don’t behave anymore. It seems that the intent of the production shares that age-old artists’ maxim, ‘to make the invisible visible.’

To accommodate 3 narrative threads about identities challenged by computerised data collection the set changes often. The video projections, moving screens and occasional props merge effortlessnessly. Despite occasional problems with the microphones worn by the performers, the technology and performers work well together, creating a pleasing aesthetic: part CNN, part Pixel Chick and part video art shown black-box style.

Prior to the introduction of any new media components into the production, a speech is delivered by a character listed in the program as The Voice of Claritas™ performed superbly by Tanya Selvaratnam. She feeds the audience data gleaned from sales of theatre tickets for the production, outlining the audience demographic. We are told that we have “above average levels of education” and are “knowledge workers”, “professionals” and have “chic connections.” This is then contrasted with the “shall we say, eye-for-a-bargain” demographic of an outer suburbs postcode not represented in the ticket sales at all.

I scan the audience as The Voice of Claritas™ speaks. Rather than feeling constrained by their ‘data selves’, they seem to sense an image that they like and, consequently, are happy to have the data speak for them. Intended to serve as an introduction to and proof of the impact data surveillance has on our daily lives, the spiel has the converse effect. The audience is rendered immune to the full potential of the production. Perhaps the true technology of performance is that which captures an audience’s vulnerability, for it is this that provides us the opportunity to question our ideas and assumptions rather than making us comfortable with the status quo. Super Vision encompasses the paradox of the 21st century Western experience: that incurable mix of privilege and constraint that brings about the condition of interface anxiety.

Super Vision, The Builders Association and dbox; His Majesty’s Theatre, Perth, 14-19 Feb 14-19

See also Jonathan Marshall’s response to Super Vision on pag 36

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 27

© Kate Vickers; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Involving direct participation, community arts and television, Digital Storytelling (DS) is also known as witness-contribution, personal storytelling, user-generated content (UGC), participatory TV, scrapbook TV, viewer TV, citizen TV and so on. DS uses digital equipment for personal storytelling or, as ACMI, hosting the Australian conference, puts it, “auto-biographical mini-movies.” DS does not usually involve sophisticated interactive systems nor does it push digital poetics. However, it is influencing mainstream entertainment more than its complex cousins.

Although events such as the National Storytelling Festival (USA; www.storytellingcenter.com/festival/festival.htm) have been promoting personal storytelling since 1973, there is only the one Digital Storytelling Festival, running since 1995 in San Francisco (www.dstory.com). The first DS conference was hosted by BBC Wales, in association with the Welsh Development Agency, in 2003 (see www.bbc.co.uk/wales/capturewales which features “RealMedia movies made and edited by people at digital storytelling workshops around Wales”).

Such is the interest, the conference at ACMI sold out before it began. According to registration data, the attendees were from a variety of sectors, mostly from schools, community organisations and academia and others: digital storytelling practitioners, new media artists, filmmakers and government personnel. The speakers were similarly representative and addressed broadcast convergence, new forms of storytelling, storytelling and the digital generation, and democratization and documentation of “voice.”

Not surprisingly some of the presentations were styled to combine fact and fiction. Nor was it a surprise, given the liberating nature of storytelling, that the keynote speaker for the conference was an active participant in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. In 1962, John O’Neal thought he’d have Civil Rights sorted out in about 5 years and then he could move onto his other passion, playwriting. Needless to say, he has continued to combine writing, performing and directing with his activism. O’Neal also participated in the first ACMI Youth Summit held parallel to the conference. He took the students and teachers through the renowned “story circle” technique before they set off to create their own digital stories. Guided by the themes of quality, diversity and respect, the students traversed the Melbourne CBD with cameras, enacting what Jean Burgess, a PhD candidate at QUT describes as “vernacular creativity.”

Like all art forms, digital works include a continuum of styles and approaches that is often subsumed in one overarching term. Ana Serrano, Director of Habitat, the new media lab at the Canadian Film Centre, outlined 6 ways audiences participate: they can “build” content, for example on Zed TV (www.zed.cbc.ca); “retell”, as with the highly praised locative arts project [murmur], (http://murmurtoronto.ca); “interpret”, as in educational simulation games such as Pax Warrior where you might find yourself in the position of a UN Commander in Rwanda (www.paxwarrior.com); “confess”, as in Things Left Unsaid (www.thingsleftunsaid.com) where you contribute your ‘secrets’ to a scenario; and “effect change” using eco-art at Seed Collective via your mobile phone (www.seedcollective.ca). The projects at Serrano’s laboratory bypass broadcasting and take to the streets, literally, utilising locative technologies.

Most of the practitioners present at the conference seemed, however, oddly unaware of new media arts. Chris Crawford, a first-breed game designer but now an ardent developer of “interactive storytelling”, patiently tried to explain to the participants that what they were doing was not interactivity. Their confused and sometimes offended reactions were understandable, considering the type of interactive storytelling Crawford is aiming at requires an approach and software that is still embryonic. Beyond the ability to change the interface or contribute content, Crawford’s newly launched software, Storytron (www.storytron.com), permits authors to create a storyworld in which the user then initiates events. Crawford’s system is unlike normal storytelling in that the author does not create a plot but rather a world and relationships between characters, ready for reaction when the user interacts with them as a protagonist.

There were many discussions about the effect of DS on the younger generation. Phillip Crawford, producer of knot at home, an interactive digital storytelling site to be launched in April and coming out of the BIG hART community projects (www.knotathome.com), shared his extensive experience of working with young people. It is not enough, he said, for them to tell their story once. They need to rewrite over time, only then can the “dominant story” be changed. Barbara Ganley from Middlebury College (US), asked what happens after a digital story is done? Interested in the “continuing, evolving, non-ending conversation”, Ganley championed the use of blogs. Discussing pedagogical benefits, she highlighted the need for students to form their own voice and feel “connected to self, peers and outside world.” Adrian Miles, active blog and vlog (video blog) practitioner and researcher at RMIT, described blogs as “the revenge of the word upon a twitch generation.” The critical difference, Miles observed, between DS and blogs is time-based: blogs are present stories and DS past ones. Miles also highlighted the shared paradigms of podcasts and vlogs and public access TV. What Miles didn’t mention, but which is relevant here, is Akimbo, a device that allows viewers to subscribe to vlogs and watch them on TV—anyone’s content, broadcast, indeed “pulled” by you to your TV.

Professor John Hartley, of QUT, reflected on the changes to television over the last 50 years. TV has moved from industrial production—a closed, expert system where ideas are protected, standardised, codified and delivered to passive audiences—to being a part of the “experience economy.” Consumers, indeed “prod-users” or “pro-sumers”, are (à la Charles Leadbeater’s “knowledge economy”) an economic force. Announcing a new UGC site, Freeload (www20.sbs.com.au/freeload), SBS’ Paul Vincent spoke about the potential (if changes to multi-channeling laws are in SBS’ favour) for digital storytelling to move off the gallery wall and onto digital TV. Broadcasting UGC through TV channels is a cost-effective way of producing content (if you mix user-vetted and gatekeeper moderation) and an efficient way of gathering viewers. David Vadiveloo, creator and director of the highly successful TV and web work Us Mob( www.usmob.com.au; see RT66, p20) warned that the move to broadcast UGC is potentially unjust if the storytellers are not remunerated.

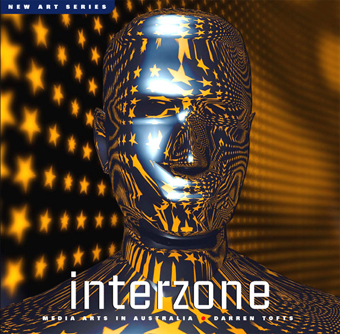

As a balance to the technology-oriented approaches, Darren Tofts, media arts academic at Swinburne University of Technology and author of Interzone (RT 71, p22-23), warned against an “over identification with the singular notion of the digital.” Beyond a production and publication device, Tofts mused on symbiotic partnerships with technology and cited the machine-human relationships explored in Zoe Beloff’s interactive work, The Influencing Machine of Miss Natalija A (2001). In a wonderfully sensible observation, Tofts reassured his audience “you will get over the medium.” In other words, you will see beyond one manner of expression and what you can do with it. Indeed, despite the digital storytelling title, there is an increasing range of media, broadcast channels and art forms available to match the many voices heard throughout the conference.

First Person: International Digital Storytelling Conference, producer Helen Simondson in collaboration with Joe Lambert from the Center for Digital Storytelling (USA); Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, Feb 3-5. Transcripts of the conference will be available online.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 28

© Christy Dena; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Robin Minard, Silent Music

photo Paul Armour

Robin Minard, Silent Music

She churns the contents of her bag around like lottery balls in a cage, looking for the keys to her apartment. Her uncapped lipstick stuck with bag-grit hits the circular staircase winding back down to the foyer, wet with second-hand rain from dripping umbrellas. A small maintenance-bot passes, climbing above her as it polishes the balustrade. Unlocking her front door she is greeted by an intimate composition of insects and trickling water quietly broadcasting from tiny speakers, fashioned within a Nouveau frieze of audio-poppies that adorn the stairwell and reach for the light streaming from a rooftop window.

Project 3 is an ambitious and provocative showcase of contemporary and historic electronic arts presented by the project’s artistic director Michael Yuen and produced by Three Reasons. Building upon an existing repertoire of works and ideas emerging from Projects 1 and 2, Yuen’s program encompasses a series of sound installations, performances, artists’ talks and public projections as part of the 2006 Adelaide Festival of the Arts.

Sonic Space

At the opening night of Sonic Space—Project 3’s concert of contemporary and iconic modernist sound compositions—I was immediately drawn to an installation of delicate matt-black speakers and cabling that climbed the pristine white walls of the ArtSpace gallery. Silent Music has travelled around the world in various guises, developed by the renowned Canadian-born composer and public sound-artist, Robin Minard. Formally the work simulates life on a variety of levels from poppies in tall grass to a cluster of single-cell organisms. Leaning in close to this exquisite installation, you hear a multi-channelled composition of water and insect sounds trickle from the ornate field of speakers. Like the designers and architects swept up by Art Nouveau in the late 19th century, Minard seems to have taken inspiration from the natural world without disdain for the artificial. In the wake of research into Artificial Life, Silent Music is a poetic response to the propositional complexity of inorganic nature.

The concert opened with Black Aspirin, composed by Christian Haines. Soaked and wooden sounds descended from ceiling-mounted speakers, like heavy drops of rain striking eaves, gutters, or instruments left out of doors. It is difficult to resist the temptation to compare these sounds with meteorological events as they affect the listener physically in the same way that elemental forces do. At one point during the piece, a storm cloud of audio above the audience bottomed out and a ferocious downpour of carefully orchestrated white noise ensued. An elderly woman in the front row clamped her hands over her ears, clearly not coping with the assault on her senses. Although the sound grew louder at this point, I don’t think the audience was beleaguered so much by the volume as the deluge of audio layers. Surrendering to a piece like Black Aspirin is an exhilarating, transforming and strangely comforting experience: like listening to a torrential rainstorm from the vantage point of your own lounge room.

The evening proceeded with a selection of historic experimental works pioneered by composers such as Conlon Nancarrow and Alvin Lucier presented by Tristran Louth-Robins. Nancarrow, a contemporary of artists such as John Cage and Elliot Carter, toyed with the inherited traditions of scoring musical events. It may have been his former career as a typesetter that drew him to experiment with the musical machine language of the player-piano, which he did almost exclusively in his later years as a composer. Audiences attending the concert were treated to a rare delivery of Nancarrow’s work on a pianola, or player-piano, specially acquired for the program. Dubbed as “impossible music” due to its polyrhythmic complexity, it is rare to see Nancarrow’s player piano works ‘live’ outside a musical conservatory or museum. Beginning with a style reminiscent of music-hall theatre, a Nancarrow piece may swiftly spiral into contrapuntal orchestrations on the exceptionally free end of the jazz spectrum. Whereas one can imagine a phantom player at the keys in the early stages of Nancarrow’s composition, such a ghost would need to grow extra arms, legs and perhaps even a tentacle or two in order to play the rest.

In homage to Alvin Lucier was a re-enactment of the American composer’s I am sitting in a room, in which a recording of an opening statement is folded back again and again into a series of recordings and re-recordings. After several iterations, the conversational fragments of this statement decay, and the audience is left with the compound feedback of the room’s variant frequencies. Lucier’s piece is intimately site-specific, relying on the nuances of each performance environment. It is possible that his work could also trigger a Zen-like total and utter annihilation of self, if not for the ‘get-up noise’ of scraping chairs, a few foldback yawns and the scratching of a reviewer’s pencil on paper.

Steve Reich’s Different Trains (1988) is evocative of the train journeys Reich made as a child, travelling between Los Angeles and New York visiting his estranged parents. Reich realised some years later that as a Jew, had he been living in Germany at the time, he would have been travelling on very different trains. The piece was originally performed by the Kronos Quartet. For the Sonic Space program, Reich’s piece was enacted with bittersweet aplomb by the South Australian based string ensemble, Aurora Strings. Different Trains is a minimalist ‘call and reply’ piece combining live performance, pre-recorded arrangements and sampled voice-overs. With great stage presence, the ensemble demonstrated a wonderful maturity of interaction with each other and with the pre-recorded compositions.

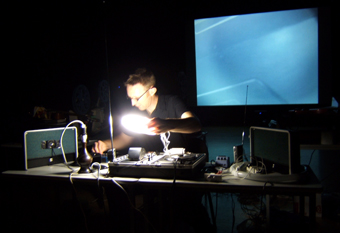

As Jon Drummond took to the stage to perform Sonic Construction 2, he had the delightful air of a guest conductor on The Curiosity Show. Coloured ink dropped into a clear vessel of water was relayed—using real time video—to software coded in Max, MSP and Jitter. The software interprets the motion and colour of the ink, triggering a sound event in a process based on the principles of granular synthesis. A sound ‘grain’ is the smallest (and therefore irreducible) particle of sound. The result is a drug-free and neurologically intact synaesthesia. Experiencing the seamless choreography of movement, colour and macro-sound in Drummond’s work lends itself to that phenomenal sensation of universal is-ness or, as a friend of mine once described it, that feeling you get when you sense the “thingy-ness of things.”

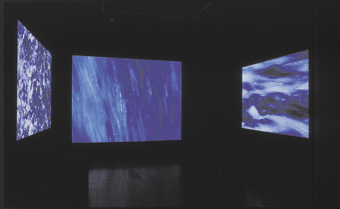

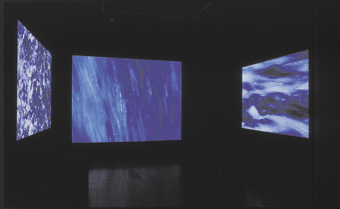

Street cinema

After a day of talks given by Drummond, Warren Burt and Robin Minard, Project 3 launched its Street Cinema program, exhibiting a selection of screen-based digital artworks over 9 successive evenings in Adelaide’s West End. The program included innovators such as Somaya Langley, Michael Yuen, Paul Brown, Warren Burt, Gordon Munro, Sonia Wilkie, Luke Harrald and Alex Carpenter, as well as James Geurts who received a commission to develop a work for Project 3. Enigmatically titled Gravitas, Guerts’ abstract video work is a painterly montage of what looks to be interference patterns from a psychic antenna, layered with thermal photographs of obscure figures and objects. The title is perhaps an intentional contrast to the nature of the piece which I read as being playful and conceptually unencumbered.

Perhaps less intentionally, several of the Street Cinema works within Project 3 bring the tenets and aesthetics of late abstract expressionism into the evolving realm of computational theory. Munro’s Evochord is a petri dish of genetic algorithms jostling to grow into something musical. Coloured points of light wriggle and swell to the discordant rise and fall of many singular notes. As if caught in a self-organising matrix, these lights collect briefly into homogenous groups of colour and sound to produce a sublime musical chord, before falling back into organised chaos.

Luke Harrald’s CONflict is a stunning synthesis of abstract sound and vision. On screen, delicate cathedrals of painterly light fade in and out to the bloom of a subtly shifting harmonic. Coded in MAX, the dynamic nature of this work is based upon the Prisoner’s Dilemma: a well-travelled model of logical probabilities used to explain the fundamentals of game theory. The screening of Monro and Harrald’s works feed directly from a computer as an application rather than being captured on DVD. This allows the process behind the development of the work to take effect: meaning that each time a viewer happens upon the piece it is unique, regenerated again and again from dynamic permutations of existing code. The difference between a static DVD recording and the use of a dynamic software application may be lost on the stroller who happens upon the work, watches for 10 seconds and moves on…but maybe not.

Innovation was evident in all the works, contemporary and historical, in Project 3, suggesting the capacity of artists and audiences to continually and mutually redefine relationships between consciousness and perception, art and nature.

Project 3, Contemporary and historical electronic arts, sound, video, installation and artist talks, artistic director Michael Yuen; Adelaide Festival of Arts, March 6-26

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 29

© Samara Mitchell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The phrase “the NOW now” was coined by English guitarist Derek Bailey, a pioneer of non-idiomatic improvised music. Bailey died in late 2005, and so this year’s festival, the fifth in an annual series, was dedicated to him.

Natasha Anderson & Amanda Stewart

photo Clare Cooper

Natasha Anderson & Amanda Stewart

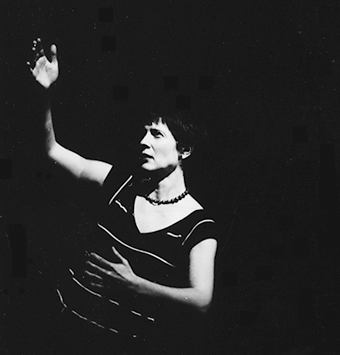

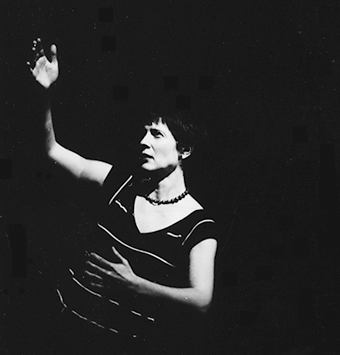

With more than 80 musicians participating, it would be impossible to cover every performance here. Given that I performed on the Friday and Saturday nights, I have chosen to write about the Thursday night, which also happened to be my favourite night of the festival.

The opening act, Robbie Avenaim and Dale Gorfinkel, are a vibraphone duo with a difference. Their instruments are microtonally prepared and activated by machines instead of the usual mallets, resulting in a variety of unusual textures. Their music was like waking up to an alarm clock, only in reverse; the hypnotic quality of the sound pulling the listener into a dream world. Alarm bells gave way to scenes of old children’s toys, followed by distant propellers and, finally, cats purring. By the end, Avenaim and Gorfinkle were literally shaking the sound from their instruments.

The Digits are a young laptop supergroup comprising Ben Byrne, Luke Callaghan, Alex Davies and Ivar Lehtsalu. They only played for 11 minutes but that was enough time to give a demonstration of the sound of systems overloading and crashing, and of faulty networks trying to establish connections. There was plenty of microsonic fetishism to be found here.

Pateras/Baxter/Brown from Melbourne played 3 distinct pieces. Sean Baxter began by dropping various objects on his ‘shit core percussion’, while Anthony Pateras’ busy prepared piano sounded like clattering tin pans in the mid range and collapsing constructions of tiny wooden blocks in the high range. Dave Brown began the next piece by scraping his guitar to produce disturbing moans before moving on to processed high frequencies and occasional boings and twangs like a ruler on a desk. For the final piece Baxter attempted to destroy a plastic plate, then turned his attention to what looked like a hubcap. The band worked itself into a frenzy which eventually broke down into a series of wobbly notes from Brown and a final flourish from Baxter.

Following a short break came an audiovisual performance by Peter Newman, one of the most impressive members of a new generation of media artists currently emerging from Sydney’s tertiary educational institutions. His music is epic, sweeping digital post-rock, like My Bloody Valentine stretched, twisted, filtered and layered into a dreamscape, the crackle of distortion matching the constant flickering of his images, which suggest faces and figures, but which I’m told aren’t actually there. The performance ended with a fade to white video and white noise. Perhaps this is what a near death experience might be like.

Natasha Anderson on electronics and recorders (as in the wind instrument) and vocalist Amanda Stewart allowed silence to be an integral part of their performance. An extroardinary range of sounds sporadically emerged and receded: whistles, breaths, kisses, twittering, chattering. It was often truly startling, with both performers demonstrating extraordinary control over dynamics and timing. They weren’t so much responding to each other as operating as one volatile unit. At times I was reminded of Luciano Berio and Cathy Berberian’s electroacoustic composition Visage, but with the operatics replaced by a 21st century microscopic sensibility.

Following another short break came one of those ad hoc assemblages for which improv festivals are renowned. Xavier Charles from France on clarinet, Jeff Henderson from New Zealand on wind instruments, Cor Fuhler from Holland on piano, Dave Symes on electric bass and Tony Buck on drums. After a long, meandering start, out of nowhere came a driving rock rhythm from Buck and Symes that got people’s heads nodding. This pattern was repeated several times, with ponderous passages punctuated by riffs and grooves, augmented by increasingly intense squeals from the woodwinds. Special mention should go to Henderson who cut an eccentric figure, moving between clarinet and sax, pausing occasionally to play with seemingly random objects on the floor.

Next was the most overtly ‘jazz’ set of the festival. Kris Wanders plays tenor sax loud, with a tone like an overdriven amplifier. The other musicians—Slawek Janicki on (often bowed) double bass, Alister Spence on piano and Toby Hall on drums—couldn’t match him for volume but instead created a dense web of notes. Some much needed space was created when Wanders dropped out, allowing us to hear the intricate interplay between Spence’s piano and Hall’s drums. Spence’s playing was a highlight, a multidimensional sound which changed shape depending on the angle from which one approached it.

The final act of the night was Thembi Soddell on sampler and Anthea Caddy on cello. Soddell has attracted much praise for her visionary and dynamic electroacoustic work. Given that some of her sounds are derived from processed cello, there was much interest in how she and Caddy would sound together. The audience was immediately transported to a haunted cavernous space, like some post-apocalyptic bunker. The scraping, screeching, creaking and crackings emanating from Caddy’s cello had me feeling sorry for the instrument. This was the sound of friction, of machinery long abandoned but still attempting to function. The scenes kept changing, but one was left with a distinctly queasy feeling that something was not quite right—an enigmatic note on which to end the night.

With nightly after-parties featuring some of Australia’s hippest underground DJs, installations, film screenings and even acoustic ecology-style soundwalks, the NOW now has reached maturity. There’s not much more that could be included, except perhaps talks and workshops. The festival and in particular its organisers, Clare Cooper and Clayton Thomas, have had a profound influence on Sydney’s experimental music scene. Overcoming the city’s tendency to cliquey fragmentation, the NOW now has pulled many people from diverse musical backgrounds into its warm embrace. It is a place where improvisation is an ethical as much as a musical approach; the emphasis on finding ways of engaging as equals. Audiences have responded with equal enthusiasm, with more than 300 people attending each of the 4 nights this year. The NOW now plays a vital role in developing local artists and audiences

the NOW now, curators Clayton Thomas, Clare Cooper; @Newtown, Sydney, Jan 18-2,1 http://www.thenownow.net

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 30

© Shannon O’Neill; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

alva.noto

photo Kenichi Hagihara

alva.noto

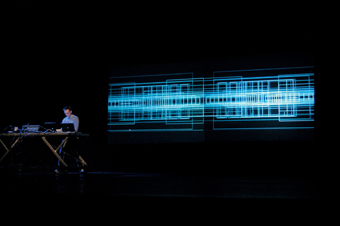

Calling for a “tuning of the world”, R Murray Shafer was influenced by Pythagoras’ concept of the music of the spheres—the harmonious hum of the universe. But he wasn’t too fond of the overcrowded audio soup that industrialisation and modern living was making of the acoustic environment. While electricity is a natural phenomenon, its technological taming is the foundation of contemporary living and one of the major ingredients of this soup. So I wonder what Schafer’s thoughts would be on Sound+Electricity at Performance Space featuring performances by Carsten Nicolai (aka alva.noto) and Joyce Hinterding, both of whom use this energy source directly to conjure their sonic worlds.

Hinterding has been summoning the hum for quite a few years now. Using large, hoop antennae, she amplifies the under rumble of the electrical grid. It is a warm, caramel sound tonight reinforced by the projection showing 2 mirrored ovals of a flowing bronze substance. Hinterding’s work is meditative, the shifts of tone minimal and incremental. At some point it becomes a duet as lighting designer Richard Manner subtly brings up dim squares of light, shifting the intensity and pitch of the drone. For those of us who have spent considerable time trying to eliminate interference between lighting and sound systems, this is a perversely pleasurable moment. Patience is rewarded with the development of crackles, pops and fizzes fringing the bass tones marking the climax of the work. At its end, there is both relief and a hint of loss plus some very strange flange effect filtering the foyer voices for the next few minutes.

In contrast to Hinterding’s slow flowing release of electrical energy Carsten Nicolai’s sound consists of tightly controlled punctuations and calculations. Nicolai describes his work as “atomising…Every particle carries the same information as the bigger object it came from…a kind of micro-macro thing” (Wire 238, Dec 2003). In this performance each sound element—spit, spark and sputter—is perfectly crafted, a glistening glitch. When these particles combine, the whole becomes an intense, vibrating composition of intricate syncopations. Accompanying the sound are synaesthesic visuals of blue lines snapped to a grid, directly emulating the intersections of audio. These form strict geometries, like insanely complex architectural drawings in constant states of redesign. The entire effect is as physical as it is mesmeric. The rhythmic entwinings create primal pulses and cool melodies which entice the body to movement. Why are we sitting in concert mode? We should be dancing!

This was perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Sound+Electricity. alva.noto is an artist who manages to bridge the esoteric and the accessible. The audience comprised elements of the local sound crowd but the larger proportion were newcomers to this kind of sound event. Of course alva.noto has international appeal but are many here aware that there is also a vibrant experimental scene happening in nooks and crannies around Australia? Hopefully Sound+Electricity not only tuned us in to our contemporary audio ecology but also to the potential to expand the audience for experimental audio.

Carsten Nicolai (aka alva.noto), Joyce Hinterding, Sound+Electricity; Performance Space, March 12

Carsten Nicolai was presented in association with the Adelaide Festival of the Arts and forma UK.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 31

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Upon my initial reading of Nigel Helyer’s “Sound arts and the living dead” (RT 70, p48), I was outraged at his complete lack of understanding of the laptop performances he so confidently criticized and so I casually dismissed his comments as ignorant and self-important, as I imagine many of my fellow laptop performers and improvisers did. However, upon further reading and discussion, I am compelled to reply, feeling that despite its verbose and at times unfounded arguments Helyer’s article does, at its heart, touch on some very interesting and important issues.

“Sound arts and the living dead” opposes what Helyer sees as a historical revisionism of recent years that posits laptop performance as ‘sound art’ at the exclusion of any and all other artistic explorations in sound, be they radiophonics, installation or the sound sculptures he himself produces. Helyer’s own practice has demonstrated an extended, and committed, interest in the sounding of objects, which may go some way to explaining his complaint against laptop performance and what he describes as its “profound level of banality.” Certainly few would argue the banal nature of the laptop and its use in performance—as Helyer points out, “personal computers are now as ubiquitous as the Singer sewing machine in the mid-19th century.” However, is it not equally valid to argue the banality of the guitar as an instrument of modern music?

Laptop performance should indeed be recognised as banal, and purposely so, but this banality cannot be explained as the result of a complete disinterest in performance or commitment to the acousmatic. Laptop performance does not exist entirely in the French acousmatic tradition, as Helyer observes. Instead, it fuses these traditions with those of popular music and more conceptual artistic traditions. Laptop performers exist as workers of ambiguous responsibility who traverse a liminal space between the roles of musician, DJ and artist.

With its banality of instrumentation, coupled with a conscious absence of gestural performance (which itself is contradictory and inevitably incomplete), laptop performance exists as a paradox, presenting an ephemeral space of sounding, grounded neither entirely in existing languages of popular musical performance, musical avant-garde nor more established artistic conventions. As such it sits uneasily between art and music as a discipline, accepted fully by neither, and instead often functioning as an exclusive sub-culture, to its own detriment.

Helyer’s problems with the form arise from what he sees as “an alarming fog of amnesia that obscures the recent archaeology of sound art and sonic performance”, allowing a “hijacking of the term sound art…and its repurposing as a synonym for laptop electronica.” And perhaps this is to some extent due to the exclusivity and isolationism I’ve mentioned as common to laptop performance. However, in constructing his argument Helyer makes the patronising assumption that those involved in cultures of laptop performance are somehow ignorant of histories of exploration in sound, citing examples such the Futurists and Luigi Russolo’s text The Art Of Noises, as well as snidely suggesting younger artists are unaware of William Burroughs, or for that matter that it was Burroughs who initially claimed “language is a virus” and not Laurie Anderson.

Most laptop performers are in fact unusually knowledgeable when it comes to histories of sound and music. And in fact many of the laptop performers in Australia have passed in recent years through the newly established university degrees in electronic and media arts now so popular at institutions such as UTS, UWS, COFA and RMIT, in which they are commonly taught art and music theory side-by-side and emerge well aware of both histories. Prior to this it seems most identified as either sound artists or musicians. However these are boundaries that remain undefined and now seem irrelevant as we acknowledge the work of artists such as Russolo, Burroughs and Cage, in which all sound stands approachable as music, and indeed all music is recognizable as sound.

Far from claiming ‘sound art’ as their own, many laptop performers prefer to consider themselves musicians or, more commonly still, retreat from the argument with mumbled comments that they just work with sound. The use of the terminology ‘sound art’ to describe performative and, frequently, quite musical sound has been championed by publications such as RealTime in an attempt to theorize an inherently elusive art form. Rather than exposing the failures or pretensions of laptop performance, what Helyer’s article highlights is a disjuncture that has emerged in Australian sound culture in recent years in the form of a generational split between older artists who have commonly worked either in the field of ‘sound art’ or music and younger artists who are now emerging in a field where the two seem almost impossible to distinguish.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 31

© Ben Byrne; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

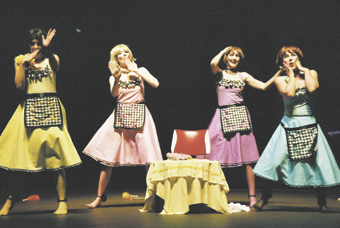

The North Melbourne Meat Market is a gracious Victorian building with a vaulted timber ceiling, wrought iron ornament and cobbled floor, part of both local heritage and contemporary culture. A huge open room that a century ago was filled with spruiking butchers haggling with buyers beneath laden meat-hooks is now filled with a hundred seats, lighting batons, projection screen, imagery of a silhouetted city and a PA—a site appropriate to performance with a viscerally urban edge.

Most of Concave City’s 7-work program is for composite art forms, including 2 works for musicians and video. Biddy Connor’s Sleep Won’t Help (2006), for clarinet, trombone and bass clarinet accompanies Kirsty Baird’s montage of old black and white footage of women in lavish costumes dancing in a humorous parody of burlesque. The video’s soundtrack of recorded laughter is morphed, serialised and segued into the score, the clarinet emitting a staccato laughter before moving onto a lyrical, narrative line. The trombone’s mournful, evaluating speech, precedes an accelerating march tempo that mocks the dreamy, lighthearted imagery. The nostalgia of Connor’s work contrasts with Arnoud Noordegraf’s Netherlands-produced 15 minute video Pong (2003), a delightfully surreal comedy depicting a man’s descent into insanity, which is quietly accompanied by Linda Kent on harpsichord.

Wally Gunn’s The Hive (2005), for viola, percussion and pre-recorded audio, evokes the 3 complementary identities of drone, queen and worker as a metaphor for industrial society. Less metaphorical but equally potent is Kate Neal’s Dead Horse 1 (2005), which opens with a driving jazz rhythm that alternates with moody rumination, plenty of contrasting colour and drama; a work suggesting the influence of composers David Chesworth and Frank Zappa. Neal’s scoring for a highly amplified ensemble of strings and electric bass and guitar captures the intensity of contemporary life.

Two works for larger ensembles, though contrasting in mood and style, are Anthony Pateras’s Fragments, Splinters and Shards (2006) and Brett Dean’s Etüdentfest (2000). Pateras’s dramatic, textured work, the longest of the evening, is for computer-based audio with viola, trombone, recorder and percussion, including some uniquely original instruments. Brett Dean’s Etüdentfest (2000) is an eloquent and mature piece for a more conventional ensemble of strings and harpsichord, opening with a moto perpetuo motif that recurs throughout. The writing is balanced and measured, building to a climax through high pitches before decaying and rising again.

The evening’s finale, Kate Neal’s Concave City & A Love Story for Two Cars (2006) is the show-stopper. In the open space between the string orchestra and the audience, 2 cars drive in, one gently crashing into the rear of the other. Two traffic-weary drivers emerge to confront each other and begin an intense, agile and at times erotic dance in, on and around the cars. The miked sounds of slamming doors, indicators and windscreen wipers form part of the score. The excellent dancers—Lima Limosani and choreographer Anton—portray frenetic urban life with power and energy, supported by Neal’s evocative composition for strings. This collaboration is the most effective and powerful blending of media in an innovative concert for the 2006 Arts House program.

Dead Horse Productions, Concave City; Arts House, North Melbourne Meat Market, Feb 10-11

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 30

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Devolution

photo Chis Herzfeld

Devolution

One hundred years ago, when Isadora Duncan was envisioning “the dance of the future”, she turned her body towards nature and moved with the rhythm of the wind and the waves. Duncan’s ecological choreography for the new century of liberation fuelled many an unburdened, barefoot dance, all free-flowing limbs and gravitational flow. Yet her cosmic view of nature’s rhythms was an enchanted 19th century romance. The futurists with their militant manifesto for arts violent and mechanic were gathering in the wings.

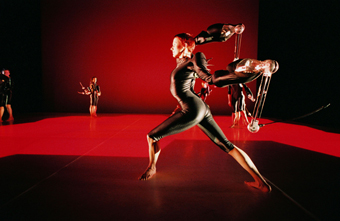

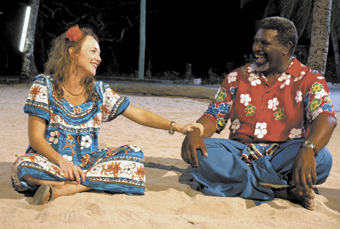

A century later, dance is a high-tech, futurist affair. Two works at the 2006 Adelaide Festival—Nemesis from Random Dance (UK, 2002) and the Australian Dance Theatre’s new work Devolution—choreographed dancers with machines and moving images on screens to digital audio scores.

The convergence of biological bodies and digital technologies is a frontier for innovation. Live performance has long served up its flesh from within a carapace of stage technology. In these new works, the techno-exoskeleton converges with the performers’ flesh on stage. Yet amidst the biotech convergence of 21st century dance, I sense how Wayne McGregor (Random Dance) and Garry Stewart (ADT) have both retained a fondness for the human body and a fascination with the natural world.

The envisioning of nature in these works trades Duncan’s cosmic vision for the minute and microscopic. The strange ways insects move—with their crisp and crunchy biomechanics, their swiftness, swarm and buzz—are traced across the choreography of both works. At times in Devolution, Stewart’s choreography recalls the movements, stranger still, of plants and protozoa.

The works are elegiac in their evocation of the human body. Gina Czarnecki’s meticulous video work for Devolution manipulates fragments of moving human flesh and flashes of X-ray skeletons. These video images, interspersed throughout the work, invoke prehuman memories of cellular splitting and ghostly after-images of bodily remains. They are haunting representations of emergence and dispersal from the past.

Nemesis

Digital video delivers humanising evocation in Nemesis as well. Ravi Deepres and Luke Unworth have designed a video montage that builds slowly, layer upon time-lapsed layer, with images of the dancers—frozen into poses of exhaustion, anguish and ennui—in the drawing room of an abandoned house. This recovered memory gives retrospective location to preceding segments of choreography accompanied by enigmatic images of other rooms from the house.

McGregor’s choreography for Nemesis is architectural and geometric. Dancers’ limbs extend along the cardinal directions outwards from the torso—back then forward, down then up, left then right. Their shoulders and their hips articulate the destinations of their limbs. Each move is plotted with the precision of a coordinate within a 3-dimensional grid.

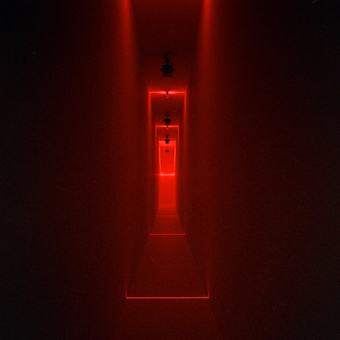

Dancers enter, walk and wait. They dance solo and with each other in pairs and trios—lifting, leaning, carrying, placing. Their costumes are neat shorts, singlets and long-sleeved tops in grey and yellow construction colours. Their trajectories are adjacent, though their relations are indifferent. The floor is lit by Lucy Carter with architectural patterns; windows, circles, shafts of light and then a grid give structure to the dancers’ positions and progressions.

Scanner’s audio score for Nemesis builds from rattles, squeaks and breathy winds to ambient chirps and vocal echoes and rises to rhythmic intensities with metallic machine percussion and techno-synth progressions for a fiery ensemble sequence. The house burns, the dancers disperse. And then we are transported—or abducted.

A dancer crawls on stage and then another. Their body-suits are cockroach-black, their arms distorted. Jim Henson’s Creature Workshop designed spikey, flesh-stripped, arm prostheses which flex and flick like insect claws. Orange hexagons tessellate the floor as more dancers enter flicking claws. An insectoid sci-fi combat scene ensues. McGregor’s prosthetic interest in extension recalls ballet’s derivation in fencing.

McGregor dances a final solo scene between 2 see-through screens: a slug-like crawl, a parasite, a worm, while animated centipedes chase each other around the screens. Four years old, the screensaver-like animation shows its age and fades. An online animation records the Nemesis sci-fi game aesthetic (www.randomdance.org). Its robotic insects, honeycomb grids and fine-line text click through to audio loops and low-grade video of the dance.

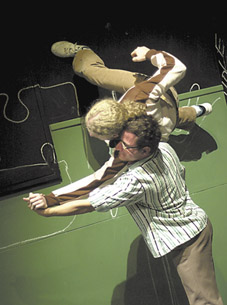

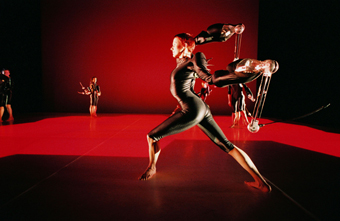

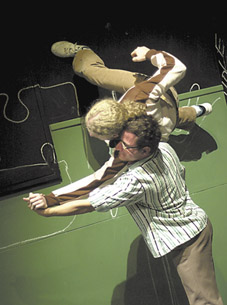

Devolution

In comparison with Nemesis, Stewart’s choreography for Devolution is fractal and organic. It grows and oozes, unfurls and folds, flips and flows. The dancers are dressed armadillo-like in layered leather skins by Georg Meyer-Wiel and they move as if by feeling, without the aid of sight.

Their heads are often down, their faces turned away. Their arms curl out, a leg folds up. Sometimes they are rooted, fixed like tripods on the spot, supported on 2 knees and an elbow, 2 feet and a hand, 2 hands and a head. At other times, the dancers travel in a pack, with arms and legs entwined and overlapping. Three pairs dance a sequence mouth-to-mouth. A man is left to dance a solo, angular and naked, but not alone.

Waiting in the wings and suspended from the rig are Louis-Philip Demers’ robots which stumble, trundle, scatter in to survey the scene. Unlike the dancers, these mechanical monsters have searching eyes—spotlights that transfix the dancers in their gaze. They intrude upon them and impinge upon their space. The dancers cower and sink beneath the awesome rudeness of the robots’ presence.

The robots’ moves are cumbersome, and sometimes cute. When it’s quiet, we can hear them creak and breathe. But when composer Darrin Verhagen’s clunking, churning industrial score lends aural power to Demers’ machines, we are witness to the mechanical choreography of terror. We hear bones crushing and flesh tearing. The dancers shrink in fear.

A robot drags a dancer across the stage and drops him. Machines attach themselves to dancers, as parasitical appendages that pulse upon the dancers’ bodies with their piston push and shove. As the end approaches, the stage is electrified with action, robots agitated, lights flashing, bodies pulsing. And then a screen descends. The final video is of a clustering of human flesh, shrinking, fading, disappearing. In the curtain call for Devolution, as if to reassure us, only the human performers lined up for the applause.

–

Australian Dance Theatre, Devolution; Her Majesty’s Theatre. Adelaide, March 3-7; Random Dance, Nemesis; Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide, March 15-18

Interviews RT 71, p 2 & 4 for interviews with Garry Stewart and Wayne Macgregor.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 32

© Jonathan Bollen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Forsythe Company, Three Atmospheric Studies

photo Shane Reid

The Forsythe Company, Three Atmospheric Studies

The dancers line up along the back of the stage. We quickly become silent. A woman and a man walk forward beneath the low hooded lights, she further than he. She contorts her body (or does she only point at him), and says: “the night my son was arrested.” His body is frozen (maybe an arm is folded over his head, his body screwed away from the audience). She walks off. And the battle begins. This is how I remember it, and I’m sure I’m wrong. And being sure is a poke in the eye about witnessing, about reporting (telling what was), and the impossibility of that, even while feeling the pleasure of telling (tales). Telling is a freedom, a fragment of freedom, and that’s what we were watching—the fragment’s brief and discontinuous circumstance.

The ‘battle’ is an endless round of violent encounters, so finely worked out that while one contemplates the improvisation of street/gang brawls, one is also amazed by the formations of the body as it fights, and the permutations of bodies as they tangle and untangle, and the timing needed to ‘get-the-job-done’ and to keep the job coming, to prolong and inflame the situation. Then a pause, a still image; the eyes rest upon a moment. It is familiar; we’ve recently seen it on the TV from Cronulla for instance, and we’ve seen it in films; we know the moves and the perpetual energy. It can go on and on, and that’s alarming; and as the bodies physically tire they become sound—gasping and grunting floats to our ears, not by dramatized force but by the real-time exhaustion of the dancers. Sound becomes dance; and sound, as much as narrative, sets up the next 2 atmospheres—compositions 2 and 3 of Forysthe’s Three Atmospheric Studies.

Giving evidence while trying to work out what happened is the atmosphere of the second composition, Atmospheric Study 2, which itself has, language-wise, several compositions to deal with (nothing is straightforward). The woman who tells her story—how she saw what happened to her son (the one arrested)—thinks she’s in composition 1, but composition 2 comes to bear upon her story and its recording, and then composition 3 does too. There are fine white threads taut across the stage, sight-lines (of fancy). She tells her story to a translator who repeats it in (is it) Arabic, transposes more like, replaces one word with another. (We know this as another man intent on describing a painting—the atmosphere of a painting, maybe a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, several of which have influenced the work). She asks the translator for the word for ‘bird’, but unfortunately the translator only has one for ‘aeroplane’, and so forth. It’s too late anyway for the woman, who in a hysterical/convulsive ‘state’ twists her body and voice in a horrible display of grief. The trouble is it disturbs nothing/no-one in the scene (life goes on). The translator watches passively, the other man keeps on ‘painting the picture.’ Forsythe has said, about the state of the war-state (world-wide): “Nothing changes. In several hundred years … nothing changes” (The Age, March 10).

And then, after a break, the third composition/atmosphere. A man begins to tell us about a photograph (perhaps it’s a fragment of the same painting in the previous atmosphere) of clouds, but more about the relations between parts, the ‘over-there’ and the ‘over-here.’ The event/bombing unfolds, the whole disaster. Amplified treated voices are wrenched through bodies, flesh slams into the set—a wooden structure wired for sound—and people curl into odd shapes, mutilated. A woman, our woman from atmosphere/composition 1 and 2, is now silent and passive while a sensible man/woman, in charge, at ease with the disaster explains it; it is all necessary and for the greater good, there is no other way, the sense of it is obvious (can’t you see that?), and s/he’s come ‘all this way’ to address just/you, to reassure just/you. Nevertheless, our woman rightly, in his/her presence, quietly dies. Meanwhile, the cloud-man has given us a tour of bits of bodies, buildings, and belongings catapulted (from over-there to over-here) into the scene.

The atmospheres are variations, continuations, escalations of the one atmosphere; glimpses, sections, diagrams, architectures of ruin embedded in live/dead beings. There is no lesson here, that’s the blessing. But there’s also no reluctance to ‘speak’, to make fury in the face of the permanent disaster; to make new problems, not take up those of the ‘authorities’—whoever they are, however they appear. Forsythe’s work is dark (darker and less abstract since I last saw it), his choreography confronts language, it pushes language outward, like the world—making matter that it is. This is difficult to achieve as language at every turn (having a life of its own) can trip itself up (be too readily sweet or bitter). It must be small and tight to keep its nerve, to know what it’s doing (and even then it goes to pieces) with sound and affect in the listening world.

Atmosphere is pervasive, it’s never this or that; rather, it’s this and that and multiple relations of infinite ambiences and densities. And it was so in Forsythe’s Three Atmospheric Studies; you had to choose what to watch and hear; to change focus was to forfeit this thread for that thread. You could not witness it all, you could not tell the whole story afterwards, only what you thought you had seen. One is unreliable like the next person, no amount of effort will ensure the truth. That’s the strange dilemma of telling and re-telling, of having the insolence (taking the uncool Forsythe risk) to ‘speak of it.’

To make a work that functions equally on several performing registers—movement, theatre, sound, voice, design—with edges of humour, intellect and poetry as well as a politic that knows what it hates, requires an ensemble of skilled dancers who are more than dancers. Timing was critical, delicacy was exquisite, and the heavy hand of ‘what it means’ washed throughout yet never erased actual endurance (on the plane of real-life, and on the plane of ‘I love to dance’ in a field of utterance—sensation). Here, more should be said about the company of dancers and about individual dancers (and about William Forsythe), but the work’s power is at the limits of these; it resides in what seems a philosophy of dance, that as time, in time, is a sort of simultaneity of realms.

The Forsythe Company, Three Atmospheric Studies, choreographer, William Forsythe; Festival Theatre, Adelaide Festival, March 12-16

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 33

© Linda Marie Walker; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

From out of the dark, to the anxious sounds of accelerated scribbling, tearing and tense breathing, emerges a quivering Fiona Malone, tightly framed by light, close to but looking through us and anxiously into herself. The torso twitches, the arms hang and jerk. A tunnel of light opens behind her. She backs along it, pieces of torn paper falling from her mouth. She is revealed again, collapsing into herself in a small square of light. Now she appears stretched out, trapped in a coffin of green light, twitching the length of her long body, arms momentarily floating, rigidifying. She reappears, half-stooped, moving towards us, almost confident, but the arms are now defensive, as if brushing something away, her head up, then down amidst oppressive crowd noises and metal raspings. In the sudden dark there are cries and crashes as her body hits the floor. In a rectangle of low light she writes with chalk on the floor, her body sometimes a template, but erasing patterns and words as she drags herself across them. For a while she looks free and fluent (even if the expression of it seems to come to nothing) and then tense as she struggles to write on her skin. Voices fill the space, speaking of loss of control and self-destruction. She erases, she writes again, she falters, she cannot bring the chalk to the floor, her arms flail about her. A spot glares from the distance, silhouetting a half naked Malone moving freely. The light then opens out into a low unbounded wash of colour and as the dancer nears us, patterned symbols form and glow on her flesh.

Fiona Malone, Reticence

photo Heidrun Löhr

Fiona Malone, Reticence

This is dance as interior monologue, where thoughts and feelings have to be read from the performer’s body (save for the one cluster of rather literal voice-overs). And what we read is anxiety about self-expression, the struggle to record or to dance it (a deliberately limited vocabulary of taut, small gestures and moves, like a body blocked). In the end, comes the recognition that all this is already written, in and on us. In this measured, nervy work, Fiona Malone displays a consistency of tone and a careful development of theme, sustaining a demanding state of being. There are occasional longueurs where small moves seems to express little (Malone stretched out in the rectangle of green light), frustration for some over the opacity of what is actually written, and a desire for the choreography to be more expansive, a little more shaped. Known for her engagement with digital technology in other works, Malone here choreographs on herself an almost animated persona, building an image from one or 2 parts of the body and small gestures, until we get the whole picture.

Kay Armstrong, a.k.a

photo Hedirun Löhr

Kay Armstrong, a.k.a

In a.k.a. Kay Armstrong appeared as entertainer in various modes across the evening: greeting us in the courtyard with glittering top hat, quips and little magic tricks; chatty dancer loaded up with professional gear like artist-as-bag-lady; dancer recalling flamenco hand moves, deftly delivered in long corridors of light, but stamping only to flatten a beckoning pack of cigarettes; and failed stand-up comic, desparate to please. Coming from the artist who gave us the powerfully performed and constructed Narrow House (RT 61, p48), this was light fare, and not enough of it written by the body.

Liz Lea, DhIVA

photo Heidrun Löhr

Liz Lea, DhIVA

Written into Liz Lea’s body are multiple histories and cultures of dance displayed with great precision, furious energy and a strength you can feel through the vibrating floor in DhIVA, choreographed by Canadian Roger Sinha. Like Malone, Lea too suggests hesitancy, intially rocking in a reflective mood on a chair before springing into action, or pausing her vigorous dance to declare, “I’m a…I’m a…” But such inarticulacy is strictly temporary as Lea flies into action. Here it’s dance as essay, informed by observations about contrasts between the Western and Eastern dance languages her body so eloquently speaks, the hybridity of ballet (its absorption of European folk dance presented here with hilariously overwrought gusto), and a commitment to Indian dance in particular.

Onextra, Solo Series #2, Fiona Malone, Reticence, lighting Clytie Smith; Kay Armstrong, a.k.a, lighting Clytie Smith; Liz Lea, DhIVA, choreographer Roger Sinha, lighting Karen Norris; Performance Space, March 16-26

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 34

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

New forms, connections, networks

RealTime 72 is rich in reports of new forms, new ways of engaging with audiences and of making new connections—between media platforms, between performance niches (as the contemporary performance touring network in Australia grows), and between nations at the Inbetween Time festival in Bristol.

John Bailey reports on recent performances in Melbourne that stretch form in new directions, making fascinating, sometimes challenging demands on their audiences (p41). As he outlines the D>Art.06 program, David Cranswick, director of Sydney’s dLux media arts, describes the blurring of media platforms and the flexibility of delivery therefore available to the makers of short films and animations (p26). Gridthiya Gaweewong, co-director of the Bangkok Experimental Film Festival tells David Teh about the festival’s innovative approach to programming and screening (p22). Karen Pearlman reviews the finalists of the 2006 ReelDance Awards for Best Australian & New Zealand Dance Film or Video, looking at the continuing challenge presented by the dance/film dynamic (p23). Jonathan Bollen (p32) and Chris Reid (p27) report from the Adelaide Festival of Arts on the impact of robotics integrated into dance and sculpture. Christy Dena attended the Digital Storytelling Conference at ACMI in Melbourne where the multiplying multimedia means of telling were in evidence, much of it online for you to follow up, with some impressive sites in Wales, Canada and the US (p28).

Contemporary performance in Australia has received a much needed boost from the establishment of the Mobile States touring consortium, Melbourne City Council’s Arts House and its Culture Lab program, Performing Lines’ continued support of innovative work, and the Sydney Opera House’s programs in The Studio and now in Adventures in the Dark. Adventures… offers a year-round international program of performance that will expand the local vision of what can be seen outside the usual arts festival context. There are now an increasing number of venues across Australia ready to take on contemporary performance and dance. Keith Gallasch surveys these developments on p38-39.

The invitation to run a review-writing workshop on hybrid art practices at the Inbetween Time festival allowed RealTime’s editors an excellent opportunity to see and discuss new British work, especially in the areas of Live Art, installation and digital media. Inbetween Time proved an idiosyncratic festival, offering audiences all kinds of access and engagement which they took up with enthusiasm (see full Inbetween Time online covereage), suggesting the direction that arts festivals of the future may well take.

Just as opportunities are slowly opening up for performance to tour Australia, cultural exchange between Britain and Australia looks set to expand. Performance Space and Arnolfini are playing a key role in this development through their Breathing Space program which this year featured Australian artists Monika Tichacek, John Gillies, Martin del Amo, Deborah Pollard in Bristol and at Breathing Space partners, The Green Room in Manchester and Tramway in Glasgow. Other Australian artists Lynette Wallworth, George Khut and Rosie Dennis were also featured in Inbetween Time.

The reciprocity evident in these exchanges is vital to their future. Wendy Blacklock, director of Performing Lines, believes it obligatory for the future of performing arts touring. D>Art.06 includes a focus on experimental film and video from the Middle East and also has invited filmmaker Akram Zaatari to the festival. By coincidence, Zaatari is one of the artists selected by director Charles Merewether for the Biennale of Sydney’s Zones of Contact, a great gathering of artists, many from the developing world.

Next

RealTime 73 will feature more from RealTime’s UK visit, including a report on the National Review of Live Art (NRLA) in Glasgow, FACT in Liverpool and Cornerhouse in Manchester. There’ll be a special focus on East London where we visited Rich Mix, a new centre for British-Asian art with a strong social agenda, and a re-vamped LIFT (London International Festival of Theatre), directed by Angharad Wynne Jones with a vision blending the local with the global. Both ventures reflect needs and conditions in the East End, and both are planning for intensive participation. In the same East End we visited the Live Art Agency and Artsadmin to discuss the unique roles they play in the nurturing and dispersal of contemporary art. RT

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 1

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Spaghetti Club, outside Arnolfini

photo Mark Simmons

The Spaghetti Club, outside Arnolfini

Located on the rapidly transforming old docks of Bristol, Arnolfini is a handsomely refurbished and busy contemporary arts centre replete with multiple gallery and studio spaces, theatre-cum-cinema, impressive bookshop, reading room and café. Arnolfini’s Inbetween Time Festival of Live Art and Intrigue proved to be an accessible, adventurous and marvellously eccentric event, prototyping a new kind of festival in which the real and the virtual blur and, above all, audiences enjoy new kinds of engagement with artists and artworks. Not only does interactivity take many shapes, digital and personal, but audiences also witness at close quarters the formation of new works.

Outside the building an old, red double decker bus, the Spaghetti Club, stood by the water, providing an all day gathering point for artists and audiences to gossip and critique, while the café was packed and the reading room in constant use. A short walk away, the L-Shed provided more gallery space. Across town, the University of Bristol’s Wickham Theatre and The Cube hosted a variety of performances.

Interaction

Large numbers of the public streamed into the This Secret Location at Arnolfini and the L-Shed, a free exhibition of works exploring the interplay of the real and the virtual. Here they saw their heartbeats and breathing writ large in George Khut’s Cardiomorphologies (Australia); they stretched out between layers of light and sound in Alex Bradley and Charles Poulet’s Whiteplane_2 (UK); activated the flight of clouds of white cockatoos to their night-time Central Australian roost In Lynette Wallworth’s intensely evocative Still:Waiting 2 (Australia); or went it alone into the light and utter dark in Ryoji Ikeda’s Spectra II (Japan). Installations were also busy: multiple screen videos by John Gillies (Divide, Australia) and Monika Tichacek (The Shadowers, Australia) and Deborah Pollard’s Shapes of Sleep (Australia) exhibiting the behaviour of very real sleeping bodies.

In contemporary art, the audience, either alone or in small groups is increasingly becoming an active participant in works of art, triggering events, slipping into immersive sensory experiences, meeting artists one-to-one in structured engagements, or simply following sets of instructions. In Inbetween Time this could range from sharing an elegant lecture-cum-meal of oysters and champagne (later followed by a brief solo visit to see the formerly tuxedoed host, Paul Hurley (Swallow, UK), transformed into a kind of oyster by swathing himself in bacon—an immaculately crafted but slender “angel on horseback” joke); joining in a conversation which is destined not to work (Carolyn Wright, Conversations with Friends, UK); a real kiss which is set in dental plaster (Charley Murphy, Kiss-in-Between, UK); sitting in on a bloody wound fabrication workshop (Uninvited Guests, Aftermath, UK); wandering the streets in headphones alert to the special sounds of Bristol (Duncan Speakman, Sounds from Above the Ground, UK); or finding yourself in a small room with a group of performers who are exploring telephone behaviour for 6 hours (Special Guests, This Much I Know, Part 2, UK).

Performance possibilities

If the public queued for and happily took to This Secret Location and other installations, another audience, often comprising students (in numbers that made us Australians envious) and performance fanciers, packed into the festival’s performance spaces.

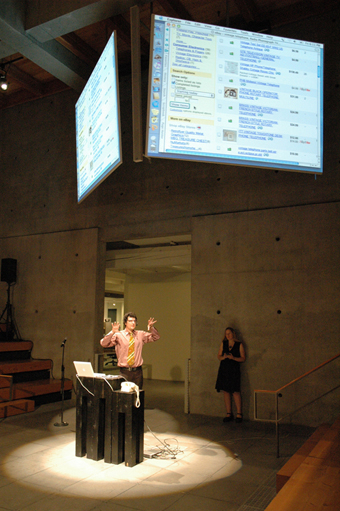

Each morning the lecture format would transform as various artists used it for everything from E-Bay Power Selling (AC Dickson, USA), to demonstrations of silent movie slapstick devices (Howard Murphy, A Working History of Slapstick, UK) and robotics (Paul Granjon, The Heart and the Chip, UK-France), and the performance company Gob Squad (Me the Monster, UK) report on their research into fear—seeking out vampires and werewolves in public places.

Grace Surman, Slow Thinking

photo Adam Faraday

Grace Surman, Slow Thinking

Other performances manifested themselves more conventionally at first glance. David Weber-Krebs (This Performance, Germany-Netherlands) turned the stage sculptural; Pacitti Company (UK) contracted us before we entered an intimate space saturated with British myth and history and reflections on our dreams and ambitions in the immaculately crafted and performed A Forest; Rosie Dennis (Love Song Dedication, Australia) seamlessly and bracingly hybridised performance poetry, physical performance and the stumblings of love; Miguel Pereira (Portugal) arranged for selected guests to murder his stage persona; Martin del Amo (Under Attack, with Gail Priest, Australia) wrestled with personal demons and Jacob’s angel; and Grace Surman (Slow Thinking, UK) duetted in surreal role reversal with Nic Green (other performers will work with Surman in other cities).

Big picture

What did Inbetween Time add up to? Whether thematised or not festivals sometimes sum up a cultural moment or epitomise a trend. As I’ve already indicated this was certainly the case with the range of ways audiences were engaged and the many hybrid forms in evidence. Tim Atack thought he detected something: “Being left hanging is a familiar motif in Inbetween Time. The themes of being incomplete, unfinished, beyond rescue or beyond recall seem to resonate through a series of otherwise contrasting works” (“Mortality Manifesto”). The fluidity of audience-performer relations and the easy interplay between the virtual and the real, self and other, body and machine certainly underlined the pleasures, in particular, and anxieties of the age with a new and pervasive intensity.

Creative tensions

The contrast between works-in-progress and complete and tested productions also provided Inbetween Time with a curious dynamic, especially given that the Australian works were in the latter category (Del Amo, Tichacek, Gillies, Pollard). Breathing Space UK counterparts will reach fruition at Inbetween Time 2007. As well, this tension extended to some contrasting aesthetic attitudes which we’ll address in the next edition of RealTime when we look at the extensive Live Art phenomenon, of which there is no equivalent in Australia. An enormous range of work is encompassed by the term Live Art, work which appears to hover between performance art and contemporary performance but is open to many more possibilities. In fact, it is most often described in terms of what it is not. Much of it seems solo, low budget and roughly crafted, with a calculated 90s anti-aesthetic or an air of intellectual burlesque and not a little bovva, but there are plenty of exceptions. It certainly has a strong institutional presence in the form of festivals, the Live Art Agency, New Work Network, Live Art Archive (its new incarnation in Bristol after a relocation from Nottingham was celebrated at Inbetween Time), well-established funding patterns, a strong regional presence, some committed venues and producers, and plenty of opportunities to work in Europe.

The Australian works were much admired, though sometimes described in terms of style, control and polish, while British live art and experimental theatre were seen in terms of conceptual power, a process orientation and spontaneity, which the Australians, in turn, sometimes read as under-conceptualised and under-crafted. The debate continued on our travels to Glasgow and Manchester where the Breathing Space Australia artists also toured, and was enriched by the experience of the National Review of Live Art at Tramway in Glasgow and our meeting with the Live Art Agency in London, more of which in RT 72. From my point of view, these differences were welcome, reflecting how different the artistic milieus are in Australia and the UK, thus making the ongoing Breathing Space exchange program between Arnolfini and Performance Space even more vital for what it offers in debate and, above all, ways of working. These creative tensions ran other ways too, even in live art itself, between younger and older generations of artists, not least in the problems of labelling. In a discussion of the issue of definition, writer Tim Atack commented, “This is a form in which the definitions are always being contested and the ground is always shifting, so let’s leave it at that.”

Thanks

Helen Cole

photo Jamie Woodley

Helen Cole

Above all our thanks to Helen Cole, artistic director of Inbetween Time, for an adventurous festival of the moment and of the future, and one which brought Australian and British artists together in a much needed and ongoing program created with Performance Space. Our very special thanks go to Helen for inviting the RealTime editors to run a review-writing workshop and securing the funds with which to do it.

The workshop was a wonderfully immersive experience with a fine team of 6 writers who committed themselves to a hard task with vigour and good humour, turning out reviews daily on demand. The writers were Marie-Anne Mancio, Niki Russell, Winnie Love, Osunwunmi, Ruth Holdsworth and Tim Atack. You can read their reviews on the Inbetween Time section of this site.

Our thanks also go to Tanuja Amarasuriya and Tim Harrison for making our 2 weeks at Arnolfini friendly, comfortable and efficient. Thanks also go to the Australia Council’s Community Partnerships & Market Development division for additional funds to extend our visit beyond Bristol to Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester and London, as part of the Undergrowth Australian Arts 2006 program.