Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/8/863_martin.jpg" alt="Samaan Michaelis, Spirit of the Walking Dead,

Shearwater Wearable Arts Awards”>

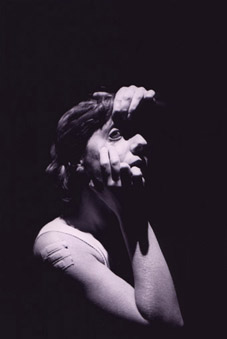

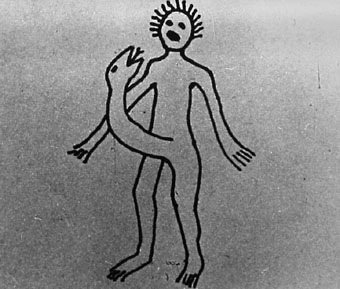

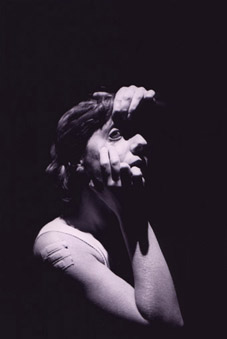

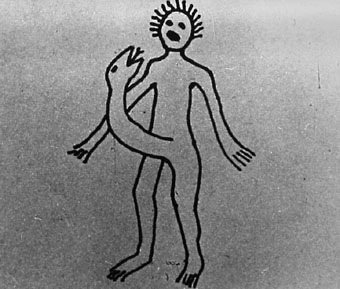

Samaan Michaelis, Spirit of the Walking Dead,

Shearwater Wearable Arts Awards

photo Jeff Dawson

Samaan Michaelis, Spirit of the Walking Dead,

Shearwater Wearable Arts Awards

From outside the NSW North Coast, Byron Bay might seem like the region’s creative omphalos. In this Newtown-by-the-beach you can’t move for poets, musicians, digital artists and visionaries. Everyone has a project. But most are just in town for coffee; artists can barely afford to live in the Bay since real estate prices hit the million plus mark. In recent years it’s more the territory of Richard Florida’s “super creatives”: retired/cashed up entrepreneurs, architects and arts executives, or those temporarily escaping the rigours of urban life.

But while wealth gravitates to Wategos Beach, the cultural ecology of the Rainbow Region is far more complex than one boho-luxe holiday spot. You have to look to the hills and valleys in the distance for creativity beyond the consumption. They host a cultural legacy based as much on alternative philosophy, spirituality and politics as a marketable lifestyle, and driven increasingly by what media studies scholar Helen Wilson describes as the “simultaneous attraction and repulsion of the city.”

Byron Shire, the most urbane of ruralities, is certainly part of the reason the North Coast ranks second among Australia’s regional areas in attracting creative professionals. It has a domestic arts tourism profile with its Blues and Roots and Writers’ festivals. Outside Sydney and Melbourne it has the highest concentration of screen industry professionals, who in 2003 hosted the first regional Australian International Documentary Conference. Briefly a radical pulse on the global electronica/rave scene, Byron is settling into the economic comfort and social hybridity of a reliable backpacker destination. However these are 1990s phenomena, pushed on by the continuous flow of bodies from polis to province.

Besides its robust Bundjalung Indigenous heritage, the coastal area from the Tweed down to Grafton has a surprising cultural vitality and distinctiveness rooted in older migrations. In documenting its transformation from a declining rural region in the 1960s to the artistic idyll of the new millennium, the essay collection Belonging in the Rainbow Region (Helen Wilson ed, Southern Cross University Press) reaches an interesting consensus. The region’s creative profile owes most to the waves of surfers and then hippies who came to the North Coast in the early 1970s, settling in the hills and valleys around Mullumbimby, then Nimbin and beyond. The influx of these “alternate seekers”, as historian Peter Cock calls them, prompted an invitation from the Australian Union of Students to host a national counter-cultural event, the 1973 Nimbin Aquarius Festival. Despite a 30 year dilution of the ideals that fuelled Aquarius—an anti-capitalist, non-violent, anarchist, back to the earth celebration—the moment arguably continues to resonate strongly throughout the region’s creative life.

Former Aquarian Christopher Dean is now one of the area’s major arts philanthropists and owner of Ballina’s Thursday Plantation Industries, producers of ti-tree oil and natural therapies products. Among other events he funds an annual acquisitive sculpture award, the largest such outdoor show in regional Australia (www.sculptureshow.net). Robert Bleakley, founding director of Sotheby’s Australia, had a juice stand at the festival. An avid art collector, he now identifies an emerging school of “Northern Mysticism”, including works by William Robinson. Bleakley rejects simplistic New Age tags for the movement, emphasising its theoretical depth and diversity, from deep ecology to shamanic spirituality.

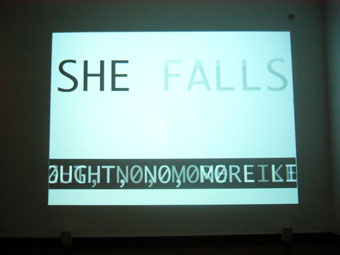

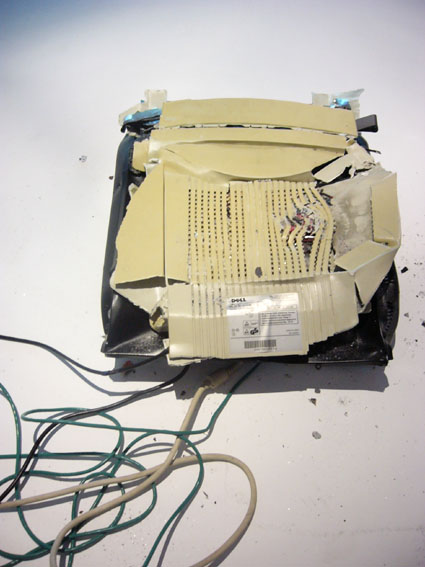

A similar transformative aesthetic imbued Mullumbimby’s fourth annual Shearwater Wearable Arts Awards, Southern Mandala, Gondwana Opalescence. The event, which attracts textile artists from across the country and involves an entire Steiner school, local TAFEs, musicians and performers, demanded entrants re-interpret the panoply of Australian mythos, with spectacular, provocative result (www.shearwater.nsw.edu.au/wearables_frmset.html).

More pervasive Aquarian ripples have spread from the region’s intentional communities, many of which were formed after the 1973 festival as a rejection of suburban consumerism (www.abc.net.au/rn/utopias). The North Coast is now home to Australia’s highest concentration of these groups. They usually share a common ethical vision and also often share land, facilities, work and decision-making. Contrary to popular myth, they aren’t retreats for drug-fucked layabouts.

Communitarians have been instrumental in establishing the region’s craft market economy, and supporting the growth of community arts. They slowly popularised the idea of sustainable housing, provoking building code and planning reforms, developing early domestic solar energy technologies and promoting eco-waste disposal technologies such as composting toilets and reed bed filters. They fought the seminal Terania Creek forest battle, giving birth to Australia’s direct action environmental campaigns (Pegasus networks, Australia’s first public internet provider was launched in 1989 at the Terania protest site).

That communitarian ethic bolsters a broader collaborative arts and performance practice: the Piece Gallery Printmakers, Nimbin Feltmakers, Byron Filmmakers Co-op and the many community arts festivals. The ethic segues neatly from older bush traditions of resource sharing, and sparks cross-fertilisation, such as when lantern makers team up with fire-workers to travel the country, or video-makers, philosophers, historians, performers and composers come together to recreate NORPA’s archetypal Flood (see RT 61, p55). It’s an environment that belies the cliches underlying cheap shots taken at ageing hippiedom. It also runs counter to the liberal argument that bohemia’s anti-mainstream ethos is a spent force, or the more recent ‘creative classes’ thesis that the counterculture’s primary legacy was Silicon Valley, with its momentary challenge to the aesthetics and experience of work. North Coast alternate seekers are still looking for meaning, and still rocking the boat.

There are predictable ecological tensions. You often encounter a Byron-is-not-us sentiment among hinterlanders, who deride its urban facade and design-is-all attitude. Nimbinians, bypassed by the real estate boom, and affluent sea-changers regard the Bay as a place afflicted with a comfortable conservatism. There’s certainly more edge at the Nimbin Performance Poetry Cup than in the marquees of the Writers Festival.

Then there’s that metropolitan ambivalence. City immigrants tend to dominate cultural planning and snap up the available arts jobs, leaving locals to carry an unenviable volunteer load. And there’s a curiosity. With all this talent flooding into the area and all the elements of a Florida-type renewal apparent, why have the region’s creative industries failed to take off and provide serious employment, rather than a handful of part-time or project based jobs?

Other struggles are bureaucratic: public liability costs demand small performing arts groups take no risks, broadband connections are endlessly delayed and unsustainable funding strategies are devised in metropolitan areas. Despite being key players in regional innovation, many local councils are only now developing cultural plans, pushed on by ministerial edict. Some are still debating what culture is or might include. So it’s the Tweed, not Byron Shire, which has won Bob Carr’s 2-year City of the Arts grant, with an ambitious cultural development strategy. The area’s voracious developers happily fund arts initiatives and market their arid coastal estates as eco-friendly. I doubt this was what the Aquarians had in mind, but it’s a fine line between transformation and co-option in the exodus north. Marcuse might have said “I told you so…”

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 6

© Fiona Martin; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

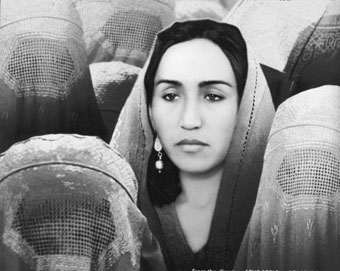

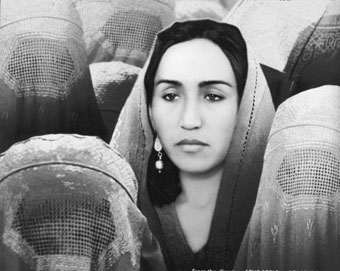

Barka Dreaming Art Camp (see note at end of article)

photo James Giddey

Barka Dreaming Art Camp (see note at end of article)

For art’s sake

“It’s been frustrating, it’s been hard, it’s been a matter of faith; and at times I’ve thought, ‘This is crazy, no one cares about the performing arts here’—but it’s also been the best working life I’ve ever had.” Lee Pemberton was an independent dance professional in Melbourne in 1997 when she felt the need for a break. She found Bega on the far south coast of NSW, had a rest, a sea change and never went back to Melbourne. Two years later, though, her hunger for dance was such that she set out to create a totally unlikely professional existence for herself in a region of cheese-making and fishing, holiday houses and skiing. Now Fling is the only regional contemporary dance company in New South Wales and one of only a small number of youth dance companies in Australia. It’s hosted workshops this year by urban pros Legs on the Wall, B Boy Swipa and Tess de Quincey, has a 9-community tour lined up for December, and is planning a season in Sydney next year.

“There’s no doubt that Fling exists because I’m a dancer, not because of local demand or as a community arts exercise”, Pemberton acknowledges. “So the outside experts were selected because of my interests—they’re a life support for me, and for the kids (aged 14 to 20) who’d soon get sick of me otherwise. I think we also gave them (the townies) a living and breathing space down here. But their work has to be blended in with Fling’s identity as a youth dance company and a regionally based one, doing work like A Dictionary of Habitats (2004), all about local environments.”

Survival and support

But how does Fling survive, even with an audience of 1000 over 8 performances for A Dictionary of Habitats? Well, it began when Pemberton marched into the NSW Arts Ministry and asked its Performing Arts and Regional officers, “How do I go about dancing in Bega?”. They were able to introduce her to the newly created system of 13 Regional Arts Boards (RABs), each with a Regional Arts Development Officer (RADO) and a Board made up from local shires and community representatives. Each RAB sends a representative to Regional Arts NSW, making for an administrative centre that isn’t about urban patronage. In the words of CEO Victoria Keighery, it’s “an outside/in model. We’re only here in Sydney to keep the profile of regional arts in the face of governments—State and Federal.”

The State is the major funder of RANSW and of the RADOs, currently to the tune of $1.5 million a year. It also funds a City of the Arts for 2 years—currently Tweed Shire—at $300,000. But there’s a surprising amount of other money out there, especially at election time: local councils co-funding the RADOs and the Federal Government’s heavily promoted Regional Arts Fund. Then there’s Playing Australia for touring and Visions Australia, which both come out of DCITA (Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts), and a comparable heritage program.

The key policy areas touted by the Ministry are summed up in the notion of active regional cultures. Regional galleries, for instance, are no longer funded on the basis of their collections, but on what they do with them and with artists. Performing arts companies like NORPA (Lismore) and Hothouse (Albury) have developed a double-barrelled producing/presenting model. New arts centre buildings like those in Port Macquarie and Gunnedah are not a “lumping together” of competing artforms in the name of economics but a “contemporary practice-driven combination” of facilities. Only in the Indigenous area has NSW been let down by a national system that fails to fund fairly by population numbers, meaning that local Indigenous organisations also dealing with housing and health are all too often overwhelmed before they even get to the arts.

Another significant factor is the different rural cycles of life. “You always have to know when harvest time is”, says the Ministry’s Kim Spinks. South West Arts RAB and RADO must have learnt that early because they’ve got a swag of projects up at Hay, such as Marion Borgelt turning her gallery mandala into a 3-dimensional maze as part of the Shear Outback project, and the earthy Outback Theatre doing workshops with Sydney’s gritty PACT Youth Theatre in their ongoing collaboration (RT53, p35).

Art solutions

There’s still more movement from the city to the bush than the other way around, despite the fact that 35% of NSW is country, compared to just 20% in Victoria and WA. But Vic Keighery foresees a reversal of that pattern. “It’s all new and fresh out there, with few competing models. We’ll soon be importing their ideas on arts tourism and program management, I bet. And there may be fewer teaching jobs for artists out there [except in music, with conservatoriums seemingly popping up everywhere], but the Lee Pembertons will stay where they are if the means are provided to keep working.”

North West Regional Arts RADO Jack Ritchie goes even further: “It’s so exciting—there always seems to be a solution, though it may take some time to discover it.” The former stage and film designer sought a mountain change 13 years ago, returning to his family home of Glen Innes. When Arts North West needed a RADO, he applied, got the job, and justified his new office being in Glen Innes. His patch spreads from Walcha to the Queensland border, and westwards from the ridges of the Great Dividing Range out to Moree. Solutions for Ritchie have come from “good partnerships”, which include a Board that mixes brilliantly with the Sydney pollies and a number of projects with the Big hART team who seem to be able to charm money from a range of both political and financial trees. Their recent film on alcohol abuse in Moree was hailed as “a masterpiece” by no less than State Minister John Della Bosca.

“Since 1998”, says Ritchie, “it’s been increasingly possible to use the arts to examine social issues. Non-arts sources will happily fund work involving young people with multiple disadvantages out here. What’s hard is for our young people to access the professional arts.”

Which is why the Carr government started a $1.9 million Arts Access program this year. So far it’s brought kids from remote areas into a visual arts workshop and allowed them to experience touring professional theatre. It’s also brought 2 isolated arts teachers into professional placements, with Coonabarabran’s Di Suthons spending 4 weeks with an Australian Chamber Orchestra that itself has recently discovered a regional/educational responsibility.

“Coonabarabran can support a thriving painting community”, says Suthons. “But it’s impossible to imagine a career as a muso there. “We had a visiting singing teacher from the Tamworth Con for a time; but her successor didn’t want to stay overnight. And we’ve managed some video conferencing for wind players with Mark Walton at the Sydney Con. But parental support for the cost of instruments and lessons is always hard to maintain—enthusiasm needs to be regenerated all the time. A conservative area doesn’t see much point in a continuing music education. But after the ACO educational event in Parkes, where Peter Sculthorpe worked on an arrangement of a Tim Whitlam song, I’m dreaming of something in Coona linking our Siding Springs telescope and the stars to composition.”

Resistance

And yet Di Suthons seems to have it easy compared to projects like Luke Robinson’s Paddock Bashin’ in Coonamble, or Kate Reid’s remarkable Brewarrina kids circus. Both are specialist artists transporting their skills westwards to work with Indigenous youth. But a comparison of the 2 projects reveals that the social one (Robinson’s) was much easier to set up, with the Attorney-General’s Department leaping on board with funds, while Reid sat out 3 years to raise the money for an artistic and skills-based effort. And now she’s doing it voluntarily from a house she bought herself when no other accommodation was available: “I just can’t walk away”, she insists sadly; “too many have walked away from these kids before.”

Both crave sustainability for their efforts, but doubt whether it’s achievable. Luke Robinson sees his mix of the physicality of drumming, the permanence of a percussive piece of public art, and the organisational skills that have already led to a youth council and a new local park, as worth franchising to other communities. “Sport hasn’t worked by comparison—it always leaves the weakest out”, he explains. “But there is a resistance to ‘the arts.’ And getting people to take ownership is hard. The schools in particular are so under-resourced.”

Kate Reid dreams of Brewarrina having a circus strand in its school that would attract specialist teachers and undoubtedly boost the 20% attendance rates achieved currently. But the educational, police and medical professionals in town are all temporary, all straight out of college, with no cultural training and no commitment. “It’s a punishment posting” she assesses. “It’s a really racist town; I couldn’t believe it. Yet somehow we took 30 kids who’d spent their lives running away from people to the Adelaide Fringe, put on 10 shows in a row…and had tears at every show. Back home, the video of the show makes people burst with pride every time they see it. Yet I’ve no idea whether it’s sustainable.”

More than art

So it ain’t all a bowl of cherries out there, despite an official spin suggesting that getting the infrastructure and the funding must lead to top people being attracted to the regions. But I can’t deny developing a warm feeling that, while in the cities, a certain pride is taken in producing art that’s hermetic and inscrutable, out bush, as Vic Keighery put it, “artists are not producing for a homogenised, commercialised market, it’s about where they live.” Is it a bit like religion? Just as the social and political aspects of church life are being expunged by uncaring fundamentalists all over the world, so art about Art has excluded community and social benefit from the equation. Except in the country.

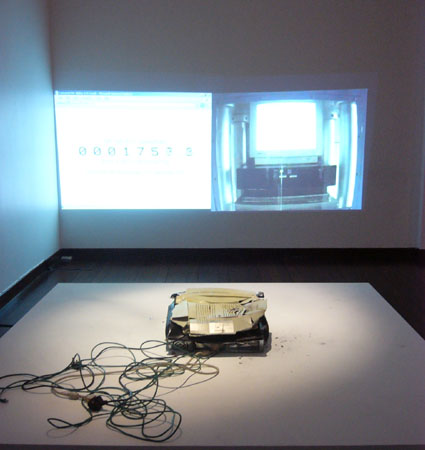

Photo: The Barka Dreaming Art Camp was a Year of the Outback event organised by West Darling Arts, the Central Darling Shire and Far West Health. The 3-day camp brought together young Indigenous people from the remote communities of Wilcannia, Dareton, Broken Hill, Ivanhoe and Menindee to introduce them to contemporary and traditional artforms and learn about their shared culture. One of the outcomes was the creation of 3 large charcoal drawings, each made up of 52 smaller drawings. The one here is a portrait of a Barkanji elder, Mrs Lulla King. It was installed in the main hall of the community centre. Two local Barkanji boys performed a dance for the elders of Menindee just prior to the community hall being decorated for that night’s NAIDOC Week celebrations in 2002.

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 8

© Jeremy Eccles; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

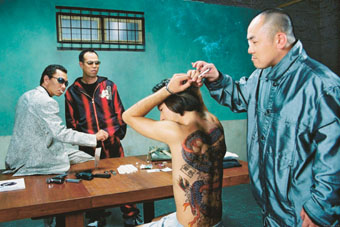

Eric Singer, GuitarBot

photo Chloé Sasson

Eric Singer, GuitarBot

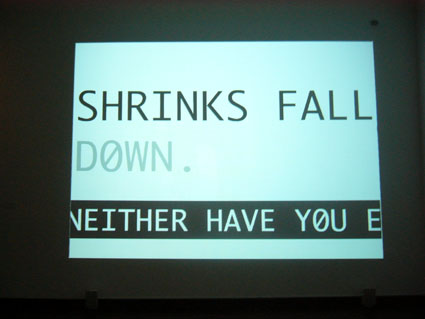

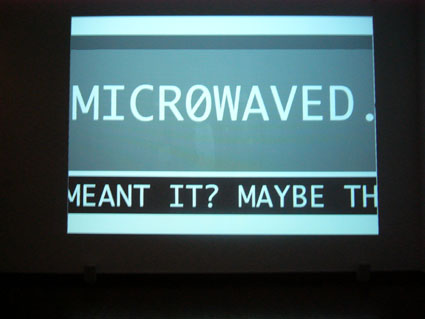

Electrofringe, the new media arts component of the This Is Not Art festival, has grown to the point where no single review can be comprehensive. There were 95 events over 5 days including panels, workshops, showcases and screenings. Over 80 contributors competed for the attention of an audience of artists, students, musicians and experimentalists.

One of the traditions of Electrofringe that allies it with academic conferences is the importation of an international luminary to cast an air of dignity over the proceedings. Eric Singer (ericsinger.com), a quietly spoken American, is one of the founders of LEMUR (League of Electronic Musical Urban Robots, www.lemurbots.org), a collective specialising in the design and construction of robotic instruments. Since its establishment, LEMUR has been responsible for a whole range of semi-autonomous noise-making machines, including the enigmatic TibetBot, a robot that plays Tibetan Buddhist bells like a demented carillon.

Singer was in Newcastle specifically to show off GuitarBot, an instrument that consists of 4 single string slide guitars complete with robotically controlled picks and servo-controlled moving bridges. Because the units resonate independently, each string can be played at a different rhythm and a different pitch, allowing for an uncanny range of tonalities. The GuitarBot then receives instructions from a controller unit which might feed it a prewritten score, or instructions generated in real time in response to a live stimulus. That stimulus can come in the form of a musician, as when GuitarBot played a live duet with the Japanese violinist Mari Kimura in New York. Each unit is approximately 3 feet in length. When on a stand, GuitarBot is at least 7 feet high and jerks and bobs on its suspension as the heavy bridges race up and down their tracks. In performance, it towers over its humanoid collaborator like a monstrous venus flytrap.

CeLL

In keeping with the theme of this year’s Electrofringe, GuitarBot was not the only musical robot in attendance. Also present was CeLL (www.cell.org.au), a creation of Nick Wishart (an original member of Toy Death) and Miles Van Dorrsen, having already made appearances at the Big Day Out and Bondi’s Livebait festival. CeLL is a shipping container fitted out with pneumatic rams that beat against the sides and frame turning the entire structure into a giant percussion instrument. The sound of the container being repeatedly punched by pistons is accompanied by giant xylophones and klaxons, all controlled via MIDI. The resultant cacophony has to be heard to be believed. CeLL sounds like an orchestrated shipping yard. Except louder.

If Eric Singer played the role of international star at this year’s festival, George Poonkhin Khut was a surprise local hero. His presentation represented the eclecticism and professionalism of Electrofringe at its best. Khut kept a small disorderly audience enraptured for over an hour in what was essentially a highly technical presentation. He works with biofeedback technologies to generate multimedia environments. In lay terms, he takes the pulse and measures the respiration of a volunteer. This information is then converted into MIDI signals (a stream of integers no different from those produced by a keyboard synthesiser) which are used to drive video and sound installations through the interpretive device of a Max patch. Max is a visual programming language that can receive and give information in multiple formats, allowing programmers to develop virtual devices, known as Max patches, to control their robots or steer video installations.

The participant in Khut’s work hears a shifting sequence of tones, depending on their heart rate, and sees a delicate pattern of concentric circles that expand and contract, the old annuli slowly collapsing into themselves to produce the impression of a 3-dimensional tunnel-of-breath. To see the patterns generated was mesmerising, but to participate was downright astonishing. Strapped into a chest-expansion measurement belt with a pulse reader attached to my wrist, I found myself steering the generation of an eerie landscape of which I had only partial conscious control. It had never before occurred to me that my pulse rate and inhalation were directly connected. A long, deep exhalation immediately lowers the heart rate. I experienced this as a deepening tone as the tunnel before my eyes contracted, and an ascending tone as it expanded. It was akin to the sort of discovery one might make after many arduous weeks of meditation in Zen boot camp, but without any of the exertion.

The discovery of the ability to influence our autonomic physical processes gave biofeedback technology its name. The technology itself dates back to the 1960s and has been studied in psychology departments and experimented with by self help gurus ever since. There is even a product on the market called CEO that allows you to see your own brainwaves for the putative purposes of self improvement. What makes Khut’s work so significant is that it brings this technology into an entirely new context. He transforms an esoteric science into an artform, fulfilling the Electrofringe promise of cross-fertilisation. It’s a difficult trick to pull off, and one that can easily degenerate into a pretentious exchange of overheated metaphors. Khut’s ability to act as midwife for his mutant project is facilitated by his excellent bedside manner—although his job title is ‘artist’, his air is of a reserved and observant scientist.

Finally, at this transitional zone of science and art, mention of Matt Gardiner’s Oribotics (www.oribotics.net) must be made. The Oribots are robotically driven origami, a group of which were exhibited at the Newcastle Region Art Gallery for the duration of Electrofringe. The Oribots began as small, compact units, and then, to the whirring of servo motors, unfolded themselves into full bloom. Lit from above by kaleidoscopic lights, the delicate paper structures seemed animated by a desire to be flowers, whose form they closely resembled. Some, and I should stress I saw them late in the festival, had so eagerly tried to become flowers that they had animated themselves out of existence. Unfolded to the point of disconnecting from the fine wires that held them in form, the dead Oribots twisted helplessly on their motorised supports.

The message at Electrofringe this year was one of inclusion: we’re all behind the Wizard’s curtain here. Anyone can be an artist, anyone can get involved. This attitude is a political one. By building robots out of everyday objects, by appropriating pop music to make mash-ups, by wiring your computer to your heart, you are fighting the overwhelming media stream. It doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you co-opt, disassemble and invent. Or as the directors of this year’s festival put it: replicate, automate, infiltrate.

Electrofringe, directors Gail Priest, Wade Marynowsky, Emma Stewart, various venues, Newcastle, Sept 30-Oct 4, www.electrofringe.net

Volunteers play an important role in Electrofringe. To keep yourself informed or to participate, sign up to the mailing group at: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/electrofringe/

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 9

© Adam Jasper; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Clare Cooper

photo Anna Liebzeit

Clare Cooper

unsound04 featured 2 days and nights of installations and performance marked by a wonderful sense of community generated by the generosity, humour and hospitality of those involved. The evening program included performances by Team Red, Lawrence English, Clare Cooper, The Von Crapp Family, Dirt Bones Assembly, The Re-mains, Bureau Infidel, Sleepville, Garry Bradbury, Lucas Abela, spbaker, ffwuc and Oren Ambarchi.

Many of these deserve more attention than space allows, and some of the performances incorporated video components that seemed underdeveloped and unnecessary. Lucas Abela’s performance lived up to expectations, with the artist, a piece of glass and an electronic current fusing in a dynamic and sustained scream evocative of the moment of birth of Frankenstein’s monster, or a cathartic electrified cunnilingus. Oren Ambarchi’s deft improvisation was an engaging, rapidly evolving stream of sound. The Von Crapp family were fantastic: the youngest family member lashed out on a mini-drum kit while dad cut up a guitar and the eldest boy played kazoo, standing in crucifixion pose and dressed in a black KKK outfit. An apt antidote to John Howard’s ‘family’-oriented policy platform and its mule-like braying of Barbie and Ken normality. However, while the performances were satisfying it was the installation program that separated unsound from other festivals.

Mutable Landscapes, a program of 7 site-specific collaborative artworks, is the brain-child of unsound04 curator and project manager Sarah Last. On Saturday and Sunday audience members travelled on a bus to visit the installation sites scattered around the surrounding countryside. The bus ride itself became a significant experience with opportunities to talk and build anticipation for the next work. Each installation was allocated a minimum of 45 minutes of listening/viewing time, allowing for a slow process of exploration, consideration and discussion.

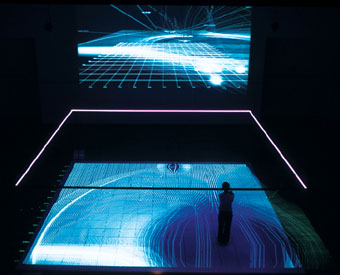

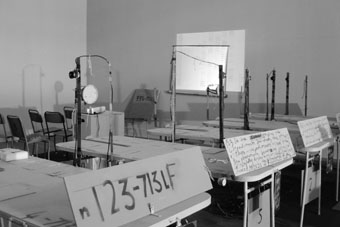

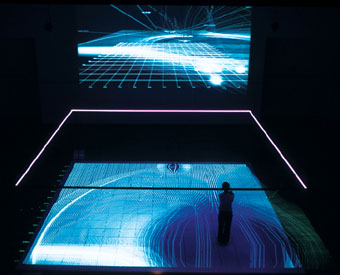

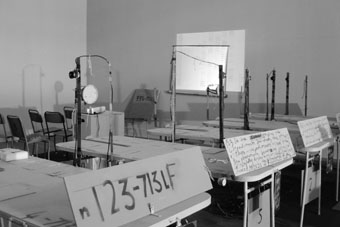

Melissa Delaney and Dominic Redfern worked together in the print workshop of the now abandoned University Visual Art Department. Their installation was perhaps the most considerate of local factors and existing content, a vivid and articulate multi-channel sound and video work. Melissa and Dom are interested in the reappropriation of space by nature, but I read the work as highlighting the absence of life—human or vegetable—within an apparently functional building. The sound composition was particularly memorable; a series of sound screens, discrete walls of mass temporarily thrown into life.

Oren Ambarchi and minus eleven error (Johannes Klabbers) presented an installation in an unlit old train carriage. The audience moved through and sat in the compartments which each contained a particular sound. Big waves of bass were felt as much as heard, with the connecting passageway containing a voice (Joseph Beuys) muttering “nee, nee, nee” at one end and “ja, ja, ja” at the other. The raw physicality of the bass contrasted with the simple philosophy of the speech, with the repetition of both parts making for a slightly hypnotic sense of abstraction.

Michael Graeve & Scott Howie, sound installation, Junee Railway Roundhouse

photo Anna Liebzeit

Michael Graeve & Scott Howie, sound installation, Junee Railway Roundhouse

Michael Graeve and Scott Howie’s installation, comprising edited field recordings and domestic turntables, was set in the Junee railway round-house, a circular structure with some 35 locomotives around the edge and a rotating turntable in the centre. It was from the centre of this turntable that the work was best experienced. The strongest aspect of the work was its use of the building’s scale, with sounds projected at the audience from across what felt like a great distance. The composition co-existed with the feel of the workshop itself—strong material at a quiet pace.

A third installation at the railway round-house was Parallax by Lawrence English and Adam Bell. Set in a small 2-room structure, the work featured the sound of a slow drip and a self-destructing speaker amplified by a 40 gallon drum. While the work contrasted nicely with the scale of the other installations, it didn’t provide quite the same open and evocative experience.

Gary Butler and Damien Gooley worked together in Coolamon’s historic Up-To-Date store. This space had a stand-offish, slightly foreboding feel, and it took 10 minutes to begin to take stock of what was happening. The key for me was a set of wired up Ugg Boots which emitted a series of sheep bleats. The ‘Baa’-producing electronic mechanism was located in a member of the small herd of lamb-sized blow-up sheep sex dolls hanging from the ceiling. I was thinking that Butler, who conceived this aspect of the work, had a refreshingly keen sense of humour until the site-specificity of the work was revealed. As the story goes, Coolamon, in the context of a civic meeting, had decided that it needed an angle to attract visitors, and selected the concept, “Coolamon, Home of the Dirty Weekend.”

Alan Lamb and Scott Baker worked together on an Aeolian Harp, the instrument from which Alan records his Wire Music. It was fascinating to see the mechanism of this music: literally a set of wires strung between 2 rocks across a slight valley, with a number of contact microphones amplifying the small sounds within the wires. These were further amplified through a car stereo and also broadcast on an FM transmitter. Listening to the music in headphones was a startling experience, as the sound of the world was silenced and replaced by the electronic whips and ringings of the wire. Ideally, the wires respond to variations in wind and temperature, creating their signature harmonic drone. In this case the wind blew from the ‘wrong’ direction, leading to an interesting discussion with Johannes Klabbers (Wagga Space program co-founder) about the incorporation of ‘failure’ in the works: “if you are going to work with nature, you have to go with it.” This work is installed permanently and visitors can be taken out to the site on request.

Sarah Last and Raimond DeWeerdt developed one of the most inventive sound installations I’ve ever encountered. Erected in a small clearing were 6 tents in which the artists were breeding flies with the intention on making them ‘perform’ by prodding the tent with sticks. Unfortunately, in the weeks leading up to unsound the weather was not hot enough to stimulate the breeding process. While the work failed in one sense, the concept is evocative, and it takes only a small leap to imagine the intensity and strangeness of hearing thousands of flies buzzing at close range.

Last has designed an excellent program, incorporating interesting sites, site-specific production, well documented artistic collaborations and an intelligent mode of consumption. These approaches are her response to dissatisfaction with the lack of inclusion of regional new media arts practice into metropolitan exhibitions and the shortcomings of the new media industry and its attendant professionals. The absence of institutional involvement, of overwhelming architecture, of security personnel and marketing hype, made clear how much these factors can distract and detract from an interesting art experience.

Mutable Landscapes was an intriguing, and satisfying program which challenged its artists through choice of sites and collaborators rather than through fatuous themes. There was not a whisper of “the work is beyond your grasp”, “ahead of its time” or “isn’t it amazing what can be done with technology?”, or any of the other excuses posed for the ongoing stream of tedious new media installations that lack ideas and/or the confidence to create an experience. Congratulations to all at the Wagga Space Program.

Mutable Landscapes, unsound04, curator Sarah Last; presented by the Wagga Space Program; Wagga Wagga, NSW; Nov 13-14, www.space-program.org/unsound/

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 10

© Bruce Mowson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

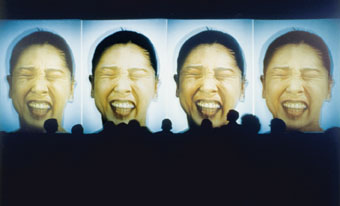

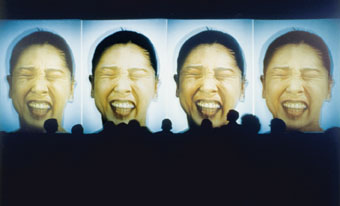

version 1.0 photo: Heidrun Löhr

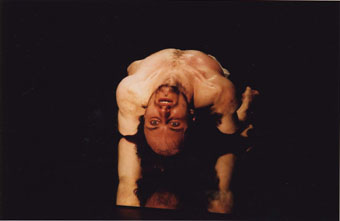

Massive though they were in scale, meticulously managed, formal in tone and spectacularly presented, the Performance Space birthday celebrations were a constant reminder of the sheer force, vulgarity, sensuality, complexity and political oomph of the work that PS has nurtured and hosted for 2 decades. This was evident not only in performances at the cocktail party for the huge number of intimates of the space and Bulls Eye, the giant public show-cum-dance party 2 days later, but also in the faux museum (objects, sounds and texts), the video selection (edited by Peter Oldham), a collection of video-taped personal recollections, 2 huge panels documenting an impressive history of artists and shows, and the photographic exhibitions by Heidrun Löhr and Sam James.

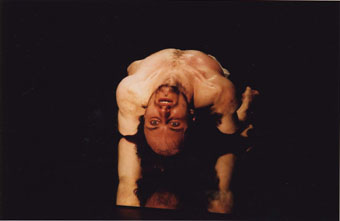

On the night of the big party, Alan Schacher’s attempt to reproduce a performative installation over the entrance to PS led to his removal by the police after a passerby thought he might be suicidal. The Sydney Front temporarily re-formed to persuade a sizeable chunk of the audience to either slip into petticoats or take off their clothes altogether and to dance with each other to the Fascination Waltz. There was no shortage of takers. Version 1.0 showing continued commitment to boozing their way through the current political depression, at least performatively, bared an arse to a rapped-up version of John Howard’s victory speech. Not subtle, but it wasn’t that kind of night.

Performance Space Patron Robyn Archer kicked off the celebrations over the birthday cake a few days before, urging debate and commitment amidst the gloom arising from the Howard election victory and Bush’s imminent defeat of John Kerry. Approving of Mark Latham’s stance on a woman’s right to control her own body when it came to abortion, she despaired at the same politician’s opposition to gay marriage: “Whether I wish to be or not, I am now an outlaw because of my sexual preference.” Archer argued the urgent need for alternative voices to be heard, emphasising Performance Space’s role in this and in its “support for local artists, but also in presenting a very special interface between the local and the international.”

The well-deserved and wildly applauded awards to Performance Space Legends (what next, PS Idol?) presented at the cocktail party in the form of plaques and framed photographs of classic performances went to performer Nigel Kellaway, architect and long-term Board member Brian Zulaikha, dance critic Jill Sykes, photographer Heidrun Löhr and founding artistic director Mike Mullins.

The one-day symposium, Performance Space: Politics & Culture, held at Museum of Sydney, proved fertile ground for what should be an ongoing discussion about the place of Performance Space in Sydney and in Australian culture and a serious opportunity to discuss its future as it nears the move to the Eveleigh Carriageworks in Redfern. From the symposium we’ve reproduced Julie-Anne Long’s personal reflection on Performance Space as building and community, specifically in its relationship with dance. Ian Maxwell, in a polemical mood, looks at the various ways Performance Space was described in the course of the symposium and the degrees to which those representations were inadequate. Hopefully Ian’s argument will provoke the debate we are all eager for. As Anthony Steel argued in his keynote address, “Very seldom do governments and funding bodies talk about the arts in philosophical terms, and it is that debate that is so urgently needed.”

Performance Space’s 21st birthday celebrations were best of all an intensely communal event, a huge gathering of former artistic directors, managers and other staff, board members, supporters, arts bureaucrats, and the many artists who have performed in that eternally transformable building. Performance Space has engendered and supported an enormous amount of work over its 2 decades and is part of a larger network to which it has contributed and which influences it in turn, including Sidetrack, Omeo Studio, Urban Theatre Projects, Pacific Wave, One Extra, PACT Youth Theatre and now Red Box at Lilyfield as well as Time_Place_Space, the Mobile States touring consortium, and the Breathing Space program in association with Arnolfini in Bristol. Performance Space is more than a building.

Congratulations to Director Fiona Winning, PS staff and additional workers, to the Board and outgoing Chair Tim Wilson, for a magnificent 5 days. Like the best of birthdays this one was rich in anecdote and history, confirmed a sense of identity (however you want to define it) and brought together a community that increasingly extends well beyond Sydney. RT

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 11

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Place

#1 The Floor

A significant defining moment for dance, especially at Performance Space, occurred when the present floor was laid. The floor is a dancer’s best friend—the spring, the grain, the feel, the blisters, the burns, the slide. It’s a very intimate relationship that the dancer has with the floor.

Russell Dumas and Dance Exchange accomplices spent many gruelling hours preparing the floor in the theatre—cleaning, sanding, coating, polishing. That was a labour of love and a defining moment for dance at Performance Space. There have been a few accidents on the floor over the years but, unlike the patchwork walls of the theatre space with the nails and hooks and holes and gaps, the floor is sacred. Cursed be anyone who damages the Performance Space floor!

When Performance Space moves to The Carriageworks, this floor will be sorely missed, its glowing reflections hard to match—there’d better be a good replacement floor or it may be the demise of dance as we know it.

#2 The Dressing Rooms

For anyone who has not experienced the glamour behind-the-scenes at Performance Space it’s hard to know where to begin. All you need to know is that there are no toilets backstage. If you remember to race to the toilet before the audience comes in, you’re fine. But if you’ve made a fatal miscalculation, the audience is seated and you don’t fancy filling any of the emergency vessels at hand in the dressing room, you realise that you have to perform those ‘amazing feats of virtuosity’ that dancers are known for—with a full bladder. On a number of occasions the discomfort of the full bladder has defined dance at Performance Space.

#3 The Foyer

Dance in Sydney is made up of overlapping, intersecting communities. The place where the collaborative processes of dance have the potential to meet and share information and experiences, to bump into each other, is Performance Space.

I’m described on the program as an “independent artist” and I was wondering when we started using the word “independent” and what it actually means. We are all dependent on each other, on other artists and on the collaborative process. I freely admit that I want to be influenced by others as a circuitous route to making my own decisions. This hardly seems independent. Many of us here are especially dependent on Performance Space for function and validity. We are dependent on audiences we know, and audiences we haven’t met yet. I like the intimacy of dance, the family created by the working process, the sociability of the post-show drink. And I propose that we are dependent on the post-show drink in the Performance Space foyer for the health of our practice.

Body

#1 The full-time Ensemble: Now Extinct

The full-time dance company with an ongoing core of performers is a way of making dance and movement that “works.” It was last seen in the vicinity of Performance Space in the early 1990s. In 1985 One Extra was a dance company with a permanent space and a full-time core of 4 performers. The company had the opportunity to employ guest artists to supplement its core cast, according to the specifics of each work.

In 1985 Rhys Martin, an early One Extra member, returned from Germany to create Dinosaur with the company in Sydney. Dinosaur was an intensely chaotic work matched by an equally intense process. The core members of One Extra for this work were Scott Blick, Roz Hervey, Garry Lester, myself and John Baylis who was also the One Extra manager at the time. We were joined by Clare Grant and Chris Ryan. Significant relationships were forged and developed during Dinosaur—Chris, Clare, John and Roz were in the original line up of The Sydney Front’s first major theatre work, Waltz, which premiered at Performance Space in early 1987. But that’s another story.

In this context I’m not interested in describing the work itself but the conditions defining this moment which centred on an ensemble of performers who had the opportunity to develop a physical practice base because they worked with each other every day. They knew each other VERY WELL—a structure which no longer exists in the small dance company strata in Sydney.

The other significant defining factor was the work’s overt influence from somewhere else. Dinosaur was clearly identified as being from “another side of the world.” At this time (mid-80s) Australian dance artists were returning from Germany, Japan, France and America with new ways of moving, and gradually over the next few years dance at the Performance Space was frequently defined by the fresh interpretations of home from these travellers.

When Tess de Quincey appeared with her haircut, strident in satin striped gown and boots, we suspected that we were in Lake Mungo, a departure from the strong pull of Japan in her earlier works. For me this work is/was a defining moment in dance at Performance Space.

Other full-time dance companies of this period who performed regularly at Performance Space included Entr’acte, Darc Swan, Kinetic Energy and Dance Exchange. Sadly, none of these survives with an ongoing group of dancers. Some of them no longer exist.

Many of us in Sydney miss the work of Russell Dumas and his special attention to bodies and light, cultivated with care over the years, at different times, with lighting designers Margie Medlin, Karen Norris and Neil Simpson. The tender partnership between Jo McKendry and Nic Sable in Dance Exchange could only have been achieved by working day in and day out alongside each other, over an extended period of time. For me, the work of Dance Exchange rarely fell short of defining moments.

#2 The Independent Artist: regularly sighted but often spotted struggling

At the Brisbane Expo in 1988. Sue-ellen Kohler was part of The Sydney Front in the street parade. Sue-ellen was a beautiful butterfly with floating lycra wings on the top of one metre high stilts. In a single moment the beautiful butterfly was caught under foot and became tangled with the ugly moth. She was pulled off and pushed back…Splat! One week in hospital, crushed T12 vertebrae, half the size at the front. That accident, on the job, in Brisbane was a defining moment for dance at Performance Space.

Sue-ellen had done a little bit of yoga practice before her accident but it was yoga that she used to reconnect with her body and get herself back onto her feet. She began to make her own performance work. It came out of her injured body experience. Her rules for making the work were defined by the body with which she found herself. An uncomfortable body, a fragmented body, a desirable body, an admirable body.

In May 1992 Sue-ellen Kohler and Sandra Perrin presented BUG Body Under Ground. It was a strange and beautiful science fiction, intensely theatrical and very sexy. They were like creatures from an underground dis/organisation. I yearn to see dance work this monstrous, this illegitimate. This was a significant defining moment in dance at Performance Space, in Australia I would say.

Many, many, many defining moments in dance at Performance Space have occurred in many, many, many bodies. Bodies walking, running and in stillness—my favourite! We have seen the body as an intelligence accumulating the information of space over time. I personally am attracted to the small moments of definition in my rememberings, rather than the grand epic sweeping gestures of dance in history books.

Now is not the time for detail but I would like to list some of my favourite defining moments in dance at Performance Space according to the body. I’ll put my self on the line and apologise profusely for omissions which I’m sure I’ll think of tomorrow.

The silhouette of the archetypal mythical feminine creature which was Nikki Heywood’s locker room mutation is etched forever on my retina from Creatures Ourselves. Oh, the agony of the Burn Sonata family. Ben Grieve and Claire Hague screaming in their shells. Anna Sabiel defying gravity in Tensile, her body balancing under and inside her structural scaffolding exoskeleton. We didn’t see enough of this. The Sydney debut at the Performance Space of Chunky Move at the end of 1995 amidst a flurry of media activity. The exciting quality of movement, comic representations. It seemed a shame to lose them to Melbourne. Garry Stewart’s extremes of the body as spectacle—a kind of dance sport—now reaping the benefits of a permanent home and ensemble of dancers in Adelaide. Dance Camp left a trace at the Performance Space with their Stepford Wives and inspired a generation of dancers when they delivered the Bandstand footage of a go-go dancing Graeme Watson. Kate Champion at the wall in Face Value. Katia Molino’s repeated falling in Entr’acte’s Possessed/Dispossessed. I aspired to falling like Katia. Lucy Guerin and Ros Warby in Robbery Waitress on Bail up to no good in those uniforms. George Khut and Wendy McPhee installed—haunting the gallery in Nightshift. Andrew Morrish, Tony Osborne, Peter Trotman—real men (not boys) being spontaneous. Shelly Lasica’s elegant behaviour. Trevor Patrick in costume and again in another and then the orange wall (Cinnabar Field). Alan Schacher across, around, up and down the building. Rosalind Crisp as Lucy. If you saw her you’ll remember the arc of an arm, the reach of her leg. The riotous NAISDA (National Aboriginal & Islander Dance Academy) end of year productions. Open City and their interest in engaging with the dancing body: Virginia will dance yet—wait and see. Legs on the Wall playing and fighting without a safety net in All of Me. The motor mouth of Brian Carbee. The political power of US Antistatic guest Jennifer Monson re-imagining what bodies can do and what they should look like. Helen Herbertson and Ben Cobham’s strange dark world (Morphia Series). An erotic equestrian scenario from Lee Wilson and Mirabelle Wouters (Sentimental Reason).

What about… (SHAKE HEAD FROM SIDE TO SIDE THEN CHANGE TO HANDS) Martin del Amo’s head and (ROLL HEAD SLOWLY BACK AND UP) …and the experience of being inside Gravity Feed’s Monstrous Body.

Why didn’t we see more of that? Did we have to have so much of that? Well, who am I to say. It’s just what I like. It’s hardly dance sport, there’s no points system and there are only the rules you make to suit yourself.

#3 Short Works—Missing in Action

Bring back Open Week—the Good, the Bad and the Ugly, where the theatre was provided free of charge to a range of performers (usually over 100 during the course of the season) from a multiplicity of backgrounds, having a chance to strut their stuff and swap ideas with other artists and their audiences.

Bring back The Dance Collections originally produced by Chrissie Koltai and Jenny Andrews and Dance Base. Copping a bit of flack, these non-curated events were always a hit and miss affair. But they did give dance artists the platform to make the short work—I love a short work. You’ve got to be making it, working at that craft somehow, anyhow, to develop. I say bring them all back, the more the merrier. We’ve got to stop thinking we have to “produce” work all the time, we need places to show it along the way and move on. We’ve got to stop only showing what is considered a finished work when it really isn’t, claim opportunities for unfinished ideas, incomplete, totally baffling moments of dance at Performance Space.

The three Steps programs presented by Theatre is Moving and the Performance Space were curated by Leisa Shelton who was very clear about what she was doing and starting, dealing with dancers/performers in a transitional phase from working in a professional dance company (not many of them around any more) and moving towards working independently. It was an establishing stage rather than a wholly initiating one and the fact that it was curated was important.

Performance Space produced many event spaces and the much missed cLUB bENT where Dean Walsh won the prize for quantity and quality every year. Dean was the master of the short work. (I say ‘was’ because he’s currently working on a full-length work, although I’m sure he’ll come back to his roots.) Dean’s naked headstand splits got a humungus round of applause at cLUB bENT but created a disgusted stir when performed outside Performance Space. The question must be asked; to go out more or to stay at home?

The Performance Space’s biennial dance research workshop and performance festival Antistatic was originally curated by Sydney based practitioners Sue-ellen Kohler, Matthew Bergan, Eleanor Brickhill, Rosalind Crisp and Angharad Wynne-Jones. It has always encouraged an intense scrutiny and investigation into the body as an intelligence. Forums, documentation and discourse are a central part of its reason for being. Dance is getting better at engaging in these ways, so let’s keep talking.

On that note I refuse to conclude because the best is yet to come, and time has run out.

–

Performance Space Symposium: Politics & Culture, Museum of Sydney, Nov 6

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 11

© Julie-Anne Long; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Any event marking a significant anniversary is bound to yield a degree of nostalgia, back-slapping and self-congratulation, particularly when old colleagues gather and are given the benefit of an audience, microphone and 20 minutes. Especially when the achievement being celebrated is so remarkable: twenty one years of Performance Space; an occasion all the more significant as Performance Space contemplates its long anticipated move to new accommodation at the Eveleigh Carriageworks. Any attempt to take up critical cudgels about such an event might be seen as, at best, churlish.

We gathered—perhaps 60 people—at the Museum of Sydney for a symposium titled ‘Performance Space: Politics & Culture’. The tone was set early. Invited to “address 3 key [Performance Space] moments” John Baylis, tongue firmly in cheek, proposed an entire narrative culminating in the Sydney Front, a group he co-founded, created and performed with throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s. The account resonated deeply with those gathered, for many of whom the Sydney Front’s work was deeply affecting, powerful and formative. For this constituency, Baylis’ master-narrative of Performance Space and contemporary performance was reassuring and affirming.

But as the gathering contemplated Performance Space’s place in the cultural landscape, it became apparent that the reflective nature of the event, notwithstanding gestures towards contextualisation, could not move far beyond the limits of (Baylis joked) ‘triumphalist’ narrative.

The problem was apparent when the keynote speaker, Anthony Steel, anchored the Performance Space project in an idea about autonomous art. Steele recalled that, “When I arrived in Adelaide in 1972 I had a personal mission to bring contemporary work to the festival there—indeed I was called ‘a proselytising modernist’.” Railing against post-Coombesian Australian anti-intellectualism, Steele spoke of arts organisations’ struggles to establish and sustain themselves as a ‘front’ in ‘the culture wars’. With proselytising modernism come assumptions about political purpose, the terms of which became more and more tangled as the day proceeded. Within such a framework, Performance Space’s struggle for a place and resources easily conflates with a generalised commitment to the new (form, media, audience, contemporary-ness), the post(modern, colonial), the queer, the alternative—categories themselves subsumed under the broad rubric of avant-gardism as politics. Autonomous art and political struggle become annealed. Any otherness, opposition, post-ness, or novelty, any alternative practice, becomes a progressive politics.

Later, Ross Gibson and Marian Pastor Roces argued that these terms are outmoded, embedded in nineteenth century sensibilities. Such terms are, they thought, complicit with that to which they claim an opposition, an observation which helped to clarify the day’s confusions about the relationships between, and the relative statuses of, ‘cultural practice’, ‘art’ and ‘politics.’

These confusions were exacerbated by a failure to address Performance Space as a sociological phenomenon. While speakers rehearsed arts policy/funding, rued the new anti-intellectualism, reflected on ‘the culture wars’, the rise to hegemony of neo-liberal market ideology, such contexts were only raised insofar as they related to Performance Space, and that cluster of artists, intellectuals and audiences (these categories, of course, overlapping) identifying themselves as the ‘we’ of Performance Space. Performance Space as itself, a social field, potentially subject to sociological analysis was not discussed.

Such an analysis would understand Performance Space as a project with its own species of cultural capital, investments and constructions of value and meaning: those sustaining ideas Pierre Bourdieu called illusio. The denial of this Realpolitik, sociological dimension takes the form, precisely, of claims to transcendental aspirations: (pure) art, an assumption of an undefined progressive politics, and so on, in the context of which Performance Space as a social phenomenon is rendered as transparent cipher, an unproblematised, invisible given.

That this is a problem became apparent in the middle session, ‘Emergent Space-Bridges to the Future.’ First, Keith Gallasch proposed a metaphorical reframing of the Performance Space project, drawn from a dog-eared text on emergence theory: slime mold, a microorganism able to meld, in times of environmental crisis, into a pseudo-macroorganism, drawing strength from temporary homogeneity, before, upon the emergence of more favourable conditions, breaking into individual spores, propagating far and wide. Mutable, self-effacing, unglamorous, resistant to all manner of predator or turn of environmental event, the metaphor drew nods of recognition and understanding: clearly for this audience there was something both phenomenologically resonant and ideologically appealing in the anti-aesthetic of slime. Extending the metaphor, Gallasch invited us to consider the cultural landscape as an ecology, replete with micro-climates, foodchains, symbiosis and, I suppose, competition.

The metaphor is at once compelling and repulsive, offering spaces, evoking ideas of diversity and inter-dependence, satisfyingly organic, and gesturing to a progressive (green) politics. At the same time, it readily lends itself to pseudo-Darwinian ideas about fitness, and to a determinism devoid of agency. Everything becomes a natural process, echoing Baylis’ earlier ideas about the inevitability of the Sydney Front’s emergence. For what it is worth, Gallasch’s account of his own engagement with Performance Space took the form of an elective affinity: Performance Space drew him and his company, Open City, almost alchemically: “we were looking for such a place.” Again, the narrative, although accommodating some agency (Open City did, after all, go looking) creates an inevitability, a sense of things finding their right balance.

And of course, the ecological metaphor brings with it ideas about conservation, sustainability, balance: a natural order of things. Sarah Miller, speaking next, invoked a ‘we-ness’ charged with “holding onto” those things that Performance Space achieved, made possible, stood for. Then Nick Tsoutas, again invoking a ‘we’ charged with the responsibility for carrying the flame, lamented the invisibility of ‘the next generation’ of performance workers: “I can’t see them”, he cried, scanning the audience. Finally, Mike Mullins exhorted ‘us’ all to “slow down”: to resist the pressure to create “the new”: to instead take time out to reflect, to thicken our engagement with ideas, practice and so on. His entreaty was a categorical imperative, again with a nebulous, inclusive ‘we’ positioned as the subject: we must all slow down.

Now, I do not, for a moment, wish to disparage these 3 speakers, all former artistic directors of Performance Space, all provocative, committed contributors to the vitality of the field. Indeed, they are among the handful of people who made the field. Nor do I want to indulge in a coarse generationalism, on the model of Mark Davis’ Gangland. (At any rate, I am of the older generation, a tenured academic and part of the establishment. And for what it is worth, I sympathise with Mullins’ imprecation for a radical slowing down. But that is not the point here.)

The point is that the ecological metaphor, the construction of a natural order of things and a supposedly inclusive ‘we’ constituting a kind of meta-agency or collective subjectivity (a slime mold), co-extensive and identified with the totality of the ecosystem (‘we are the field of contemporary performance’), yields an understanding in which difference—in this instance, the ‘next generation’—is necessarily invisible. And this creates the possibility of dismissing the aspirations of the next generation, in the name of that all-encompassing ‘we’ that must slow down.

The inclusive ‘we-ness’ extends to a collective self-recognition—of performance style, of belonging, of feeling at home-that functions to exclude, a possibility that, with one exception, was not raised throughout the day. Let me explain.

Baylis’ determinist narrative was bound up with an idea about a house style identified with Performance Space. The inability to describe the Performance Space house style in anything other than the broadest terms (ie that which inevitably emerged; that which we all recognise without having to define) misrecognises the significance of house style as a discriminator, the role of taste-makers and gatekeepers. Placing the various practices that took and take place at Performance Space within broad rubrics such as ‘contemporary performance’, making a virtue of an apparent lack of formal or generic consistency across the spectrum of that work, and producing a history and organising metaphor devoid of agency (Performance Space necessarily produced Sydney Front; we are slime mold), masks the agencies, labour and practices of inclusion and exclusion that constitute Performance Space as a social entity. Instead, the insiders—those subsumed under the ‘we—understand their practice as open, natural, and self-evidently progressive.

From the outside, things look very different. The only moment all day going anywhere near acknowledging this was Jane Goodall’s description of her first Performance Space experience. The ultimate outsider experience: driving from Newcastle (subtly evoked as a cultural other to cosmopolitan centre), wearing pink jeans and t-shirt—the ultimate outré. Of course, on arrival, everyone was wearing, in Goodall’s recollection, “110% black”. My point is not ‘what’s wrong with pink?’, but to notice the self-evidence of the pink faux pas. Goodall’s self-deprecatory mocking of her dress sense played upon the insiderness of her audience: ‘everyone’ knows that Performance Space habituées wear black. More than this, however, those who belong with Performance Space experience that belongingness in an easy, natural way that outsiders simply do not share. They may aspire to share it, but must do so not by sharing a(n ill-defined) politics, education, class, appreciation for art, but by means of a certain process of habituation that, necessarily, is informed by politics, education, class etc, but manifests as a feeling-for Performance Space-ness: precisely what Bourdieu means by his term habitus.

Revealingly, aside from Goodall’s anecdote, none of this came up in the course of the day. When something like a ‘feel for Performance Space’ did arise, it was negotiated in the quasi-mystical language of ‘feeling for place’, understood as a kind of haunting of the physical environment by use, artistic practice, evocative anecdotes and so on.

So, the ‘we’ misrecognises its own contingency, its grounding in a social milieu. Instead, it aspires to the totality of a cultural landscape. The ‘we’ starts to negotiate the future, expressing a concern for the crisis of generational succession, and a desire to ‘hold onto’ that which has been secured.

And there’s the rub. The anxiety informing Performance Space’s celebrations is that concerned with the immanent relocation to a new site: a site paid for by the NSW Ministry of the Arts, purpose-built for what appears to be, on the strength of various politicians’ testimonies reproduced in the anniversary booklet, a value-adding, productive-diversity model of arts practice. Understandably, Performance Space’s Board and management, artists, audiences, academics, old guard, new guard and so on are nervous about the implications of such patronage. The concerns are very real, and eminently practice-related: Will I be allowed to drill holes in the wall? Paper the toilets with pornography? Mess with the seating? The kinds of things with which overly sensible bureaucratic management have so much trouble. To stake a claim to holding onto past practices is, in the face of such anxieties, more than reasonable.

Yet…Speaking towards the end of the day, Marian Pastor Roces evoked the imaginary architecture of a building designed for an artform yet to be invented, a music yet to be heard. Subtly at odds with the conservationist (dare I say nostalgic?) version of the ecological metaphor, Pastor Roces invited us to consider not just what we need to hold onto, but that which we must let go. In a very real sense, Performance Space, when it moves, will end. The landscape will be fundamentally and irreversibly changed: an environmental cataclysm, perhaps, to really milk the metaphor; an errant asteroid wiping out the dinosaurs. In such times, there can be no holding on. Rather, the invisible—the as-yet unknown—will appear. In its new incarnation, Performance Space’s obligation will be to allow for those appearances—and there is a very good chance that it—we—will not recognise them. That is far more challenging than holding on, requiring a rethinking of ideas about tradition: tradition not as maintenance of a status quo, but as a continuity that lets go. Not a mere ‘re-thinking’ but, in a sense, a letting go of the assumption of the right to do the re-thinking.

Performance Space, as a tradition, as a connectedness with a past that is, genuinely, past, must be more than a re-invention; it must be an architecture for artforms yet to be invented, responsive to an as-yet unconstituted, future ‘we’. This is the truth of the ecological metaphor.

Performance Space Symposium: Politics & Culture, Museum of Sydney, November 5

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 14

© Ian Maxwell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

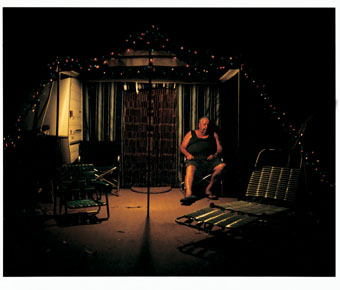

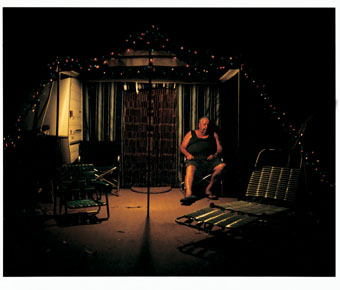

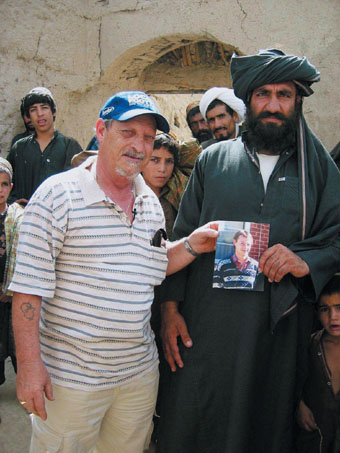

TRACKS, Snakes Gods and Deities

photo Mark Marcelis

TRACKS, Snakes Gods and Deities

In Darwin for the Indigenous Art Award and the Darwin Festival, I felt a palpable change in the mood of the place. It was brought home to me when 24 HR Art’s new media man, Malcolm Smith, pointedly drew my attention to his distinction between the louvres and the aircon people, or the Louvrists and the Aircognescenti. He knew I was an unreconstructed Louvrist while he naturally aligns with the Aircongnescenti, but he is nostalgic for the louvres as only a true po-mo can be. The distinction refers to those who hold onto Old Darwin and the new breed who want to place the town in modern mainstream Australia; for me it is about valuing the distinctive and the distance.

The Hotel Darwin has gone, the genius of Troppo architects has left (leaving behind a thriving business), and feminist historian, National Trust advocate and planning activist Barbara James has gone (to heaven). Blazez has gone and so style has left the room—in its place a homewares shop called, without any irony, Humidity. The Roma Bar threatens to close due to rapacious development. Cane toads have already reached Kakadu and they are expected in town this Wet. Central Darwin is left looking like a theme park of Irish pubs and tacky franchises. What was particular, even peculiar about Darwin is being swamped in its rush to be just like everywhere else: mirage architecture multi-storey airconditioned boxes squashed together. The Labor Party is in power but the pit bulls are still off their leashes and savaging the innocent. Small business rules supreme. Darwin’s development is a chimera as it always has been, dependent on something that’s about to happen and either doesn’t, or if it does, doesn’t deliver. The much vaunted railway, for instance, has delivered pensioner tourists who spend little and lack vibrancy and curiosity. Now Darwin waits on the disputed and morally tainted Timor gas for its next boom around the corner. The pipeline has replaced the railway line.

TRACKS, Snakes Gods and Deities

photo Mark Marcelis

TRACKS, Snakes Gods and Deities

We were at the opening night of Surviving Jonah Salt, a collaboration across the tropics between Darwin’s Knock-em-Down Theatre and Cairns’ JUTE. Brisbane-based Darwin writer Stephen Carleton, Darwin’s Gail Evans, Alice Springs’ Anne Harris and Cairns-based Kathryn Ash wrote the play, based on a proposal by Carleton: one place, 3 ways, a roadhouse midway between Cairns, Darwin and the Alice. Four characters (one per writer) leave home and meet there. In the second act they collide. Realised by JUTE director Suellen Maunder and performed by Darwin’s Mary Anne Butler and Tessa Pauling and Cairns’ Susan Prince and Nick Skubiji, it opened in Cairns to rave notices and returned to Darwin in triumph.

On opening night Playlab Press launched From the Edge: Two Plays from Northern Australia, which included Surviving Jonah Salt. The mood was high and the vibe good, a sense of relief in the air. Heart stopping performances and taut classic drama in the vein of Tennessee Williams (must be that steamy weather) with a dash of magic realism. Among all that class, Carleton’s writing and Pauling’s performance as the Valley tart Patricia stood out.

The relief was due to the fact that in the same week another new play opened on the big stage at the Entertainment Centre. Tin Hotel by Darwin Theatre Company was jointly written and directed by Gail Evans and Tania Lieman. Publicity was everywhere, and with a large local cast, expectations were high. The cast was solid, the musical direction by Merrilee Mills good, the design by Kathryn Sproul stylish. The concept and writing were problematic; it was uncertain where to pitch its tent. Was it a feelgood musical about multi-racial Darwin, like Bran Nue Dae? Or a searing racially driven tragedy with wild comic overtones, like Louis Nowra’s adaptation of Capricornia? If it wasn’t either of these, then what and where was it? Its grasp of history, politics and race relations was sentimental and naïve; scenes were short and ‘cinematic’, meaning quick edits which on a big stage with a large cast became ponderous. Often the scene changes seemed longer than the action. It felt as if it was constantly about to go deeper, develop an idea, a character, a conflict, but shied away every time. There was potential for something else in the opening and the scenes involving the 3 town gossips, led by the redoubtable Kay Brown in a marvelously black performance.

I started hearing that people are sick of historical plays, bored by theatre about the place, asking “why can’t we just have some solid plays about somewhere else?” They reckon they’ve had too many, which as a Louvrist who has championed a regional identity I found disturbing and confusing. Further questioning revealed that it was alright if it was good; they all agreed for instance that The Pearler by Sarah Cathcart was fine (RT63, p44).

WordStorm, the NT Writer’s Festival had successfully negotiated the regional-national nexus, typified by the involvement of nationally significant writers such as Barry Hill, Neil Murray, Nicholas Rothwell and Peter Goldsworthy—all of whom passionately engaged with the Northern Territory in sessions alongside locals like Andrew McMillan, Stephen Gray and Sandra Thibodeaux. The event included masterclasses, debates, songwriting and ‘how to’ sessions—a proper writer’s festival, not just a publishers’ feast. All the words I heard about the ‘Storm were positive and a tribute to the vision and organisation of Mary-Anne Butler, director of the NT Writers Centre. True North, an anthology of contemporary writing from the NT, edited by previous director Marian Devitt, was launched at the ‘Storm.

There is a strong sense that Darwin has changed and few are comfortable with the level of unbridled development. The opening scene of Tin Hotel combined news footage of the wolve’s-hour demolition of the Hotel Darwin with a dance routine in which everyone brandished the ubiquitous hot pink plasticated cardboard development signs. Winsome Jobling’s entry in Sculpture in the Park also echoed the concern. She constructed an entire estate of tiny ticky tacky boxes by carefully cutting up the pink signs. Glimpse, the winning work by Tobias Richardson, was a clever tilt at the bland-ising of the city. The title referred to an aqua blue paint that has been used for all the street furniture in the City Mall’s most recent refurbishment. Richardson painted dozens of household objects with the colour and placed them throughout the mall, making them so indistinguishable it took several circuits to identify the ring-ins.

Tracks’ new show Snakes, Gods and Deities was a reminder of what Darwin can do better than most other places: the outdoor, site specific event. Conceived by Tim Newth and directed by Newth and David McMicken, the show was a cultural exchange arising from Newth’s residency in Sri Lanka. It brought 3 dancers and a drummer from the Sama Ballet to Darwin and teamed them with local dancers and musicians. The show included seriously large live snakes, a fabulous Bollywood sequence, Maori Haka and break dancing. This was eclecticism run riot, reined in by the direction and the precision of the aesthetic as exemplified by the setting. A shimmering curtain of broken CDs was suspended like a glass prism behind the exquisite, perfectly spreading branches of a vast raintree.

Darwin does outdoors best, and the festival under the direction of Malcolm Blaylock saw the smart sound Star Shell installed in the Botanic Gardens. Every night there was a program of live music and performance that included alongside international artists Darwin’s own Balinese Tunas Mekar in collaboration with dancers and musicians from Ubud, Indigenous music and dance such as The Red Flag dancers and Yilila from Numbulwar, and Djilpin Dancers from Wugularr.

Galuku Gallery, Darwin Festival photo: monsoonaustralia.com (www.monsoonaustralia.com)

Aboriginal art was everywhere at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, in all the galleries around the town and even in the Botanic Gardens. Following on from the Garma Festival, the Galuku Gallery, or gallery in the trees, came to town for the first time. An array of wonderful coloured linocuts from Yirrkala in North East Arnhemland were hung and illuminated every evening by spotlights in a grove of palm trees. The trunks of these squat trees were ochred white, making a witty mockery of the sanitised white walls of the modern art gallery. After partying at the Festival Club in the Star Shell you could wander among the cool art in the gallery under the stars.

The final show in the Star Shell was the inaugural NT Indigenous Music Awards. The audience overflowed into the surrounding gardens where the concert and presentations in the shell were relayed onto big screens. You could picnic on the grass, watch the action and listen to the music, all for free. A Darwin experience that suited everybody: locals, tourists and those who’d come in from remote communities.

Darwin Festival, Aug 12-29

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg. 15-

© Suzanne Spunner; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

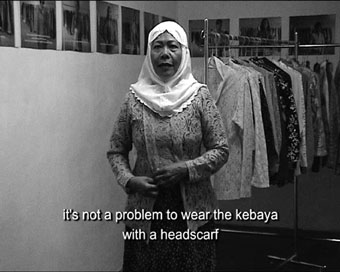

Gabriella Hegyes, en route (video still), 2003

New media art has generally been a resolutely urban affair, largely because until recently the technology simply hasn’t been available outside the cities to exhibit, let alone produce such work. However, the efforts of the Sydney-based dLux Media Arts organisation and a scattered band of intrepid regional gallery curators has seen a steady growth in the exhibition of screen-based works outside cities. While these works are not necessarily representative of the full spectrum of new media art, they indicate a significant break with the forms that have generally characterised exhibition in regional areas.

Tour dLux

Since 2001 dLux Media Arts have been assisting in touring and staging exhibitions of digital media art across NSW through their Tour dLux program. For dLux director David Cranswick, developing an audience for this work in the regions has gone hand in hand with building support in the curatorial community. The organisation has been able to provide invaluable advice for galleries not familiar with the requirements of computer technologies or the challenges of exhibiting multiple works, many with an audio component. The Tracking exhibition at the Bathurst Regional Gallery in mid-2003 was a Tour dLux initiative, and provides an interesting case study of how the program works. Gallery Director Alexandra Torrens explains: “For us it was one of our first focuses on new media…dLux were basically offering to bring out a curator with new media expertise…[Aaron Seeto, at that time director of Gallery 4A in Sydney]…to work with artists in our region…and to bring the media into the art gallery for the first time.”

Bathurst

Seeto sought out 3 artists living in or near the Bathurst region and commissioned them to produce works specifically for the Tracing exhibition. Local artist Gabriella Hegyes produced en route, a video installation about her experiences fleeing Hungary as a refugee in the 1970s. Brad Hammond, a South African artist who had recently emigrated from Paris, contributed the video work El Nino. Blue Mountains new media artist Andrew Gadow created Inverse Maps, a sound and video work about the old roads across the Moutains and out to the state’s west. The artists also ran a series of workshops through the local TAFE in conjunction with the exhibition.

David Cranswick sees the direct personal involvement of artists in the Tour dLux exhibitions as vital. Their presence through gallery talks and workshops allows regional audiences who may not be familiar with digital media art to ask questions about the processes that go into the creation of such work.