Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

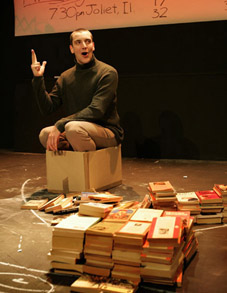

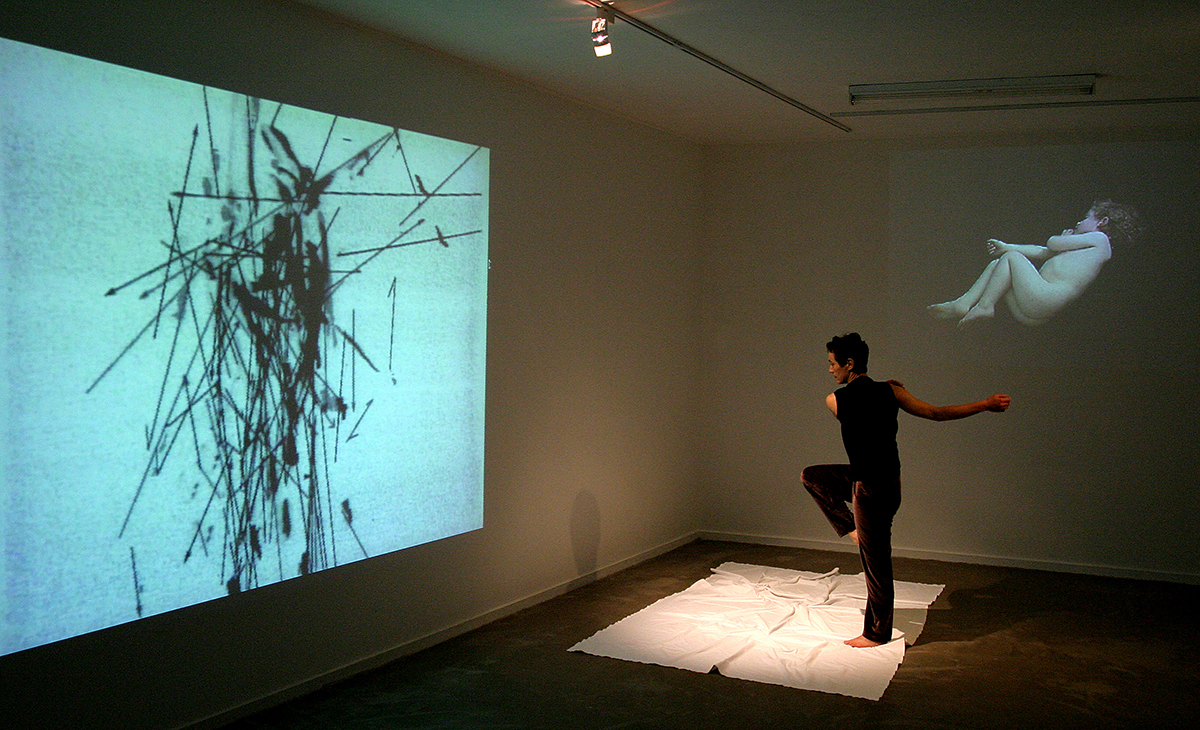

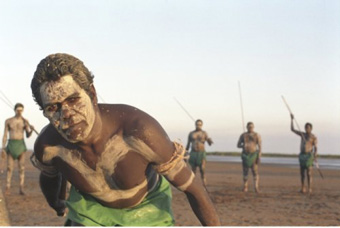

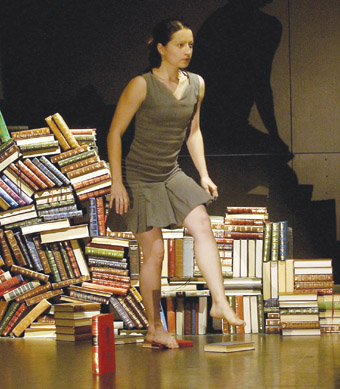

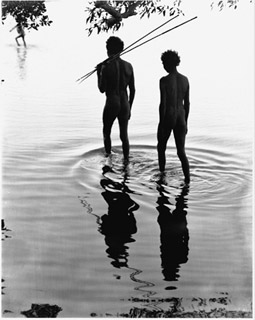

Jason Sweeney, Babushka

photo Peter Heydrich

Jason Sweeney, Babushka

Nostalgic and wistful, Ingrid Voorendt’s Babushka is a mixed media performance featuring the talents of some of Adelaide’s most interesting independent artists. Produced as part of Parallelo’s Open Platform (POP) initiative, this historical reverie was created from the performers’ childhood memories with selective interpretations of family life, dreams, aspirations and regrets. Voorendt fashioned the performance around re-enactments and responses to moments past.

The Russian Babushka doll is employed as a metaphor with small scenes recounting personal history embodied and voiced by Helen Omand, Naida Chinner, Solon Ulbrich, Astrid Pill, Jason Sweeney and Zoe Barry. The performers reminisce as they dress up in their parents’ and grandparents’ clothes and step into their shoes. We see a combination of tableaux gleaned from photographs and movement choreographed through gestural references, all bound by a motif of running that slows, halts, repeats, races and drags like childhood memory.

The 6 performers create parallel journeys inside a child’s playroom. Designer Justine Shih Pearson’s scaled-down glasshouse could also be a transparent doll’s house modelled on the venue for the performance, the auditorium at the Art Gallery of South Australia. The children’s toys, which are at the same time creative tools for the performers, are arranged prettily and metaphorically to illustrate their personal recollections. There’s a giant dress, piles of toys, tea sets, some electronic equipment and old shoes. This installation of micro-worlds implicitly invites the audience to respond with their own childhood memories.

The distinction between the real world of children and Voorendt’s theatrical excursion is that children generally act out imagined futures whereas the players, dressed in mostly 1940s style, act out family memories in the guise of children and portray childish actions. An exception is the moment when Helen Omand dons some trainers and sprints around the room expressing concerns about her age, marital status and past achievements. Naida Chinner’s solemn drinking circle in which she skols shots of white liquor in quick succession is also distinctly adult. Here the performers might be reflecting on their present lives or on the actions of parents or grandparents. The origin of the actions appears to be purposely ambiguous.

Aside from a shared European heritage, each performer’s journey appears unrelated to the others. The standout performance is from Astrid Pill who uses her beautiful, classically-trained voice to express sentimental emotions derived from Naida Chinner’s memories of her grandmother. The Latvian lullabies she sings are poignant and haunting. Pill’s performance is captivating and slightly spooky, her grounded physicality working against any overly nostalgic interpretation. Her wonderful rendition of David Bowie’s Let’s Dance, accompanied by Zoe Barry on piano accordion, is a highlight. Likewise Helen Omand’s comic ability comes to the fore as she energetically demands attention from everyone in the room with a noisy pair of kid’s slippers and then attempts to integrate herself into family portraits via some tempestuous posturing. Solon Ulbrich’s eloquent movement and muttering vocals perfectly illustrate a stoic domesticity. Later he dances cheek to cheek with Naida Chinner who, throughout the piece, appears curiously lost in her own world while simultaneously in constant flight.

Jason Sweeney’s soundscape is appropriately subtle, punctuated at one time by the voice of Omand’s grandmother telling an animated story about a goanna and at another by the melody of Puff the Magic Dragon that locates the work in an imaginary, childlike realm. Both Sweeney and Pill speak the unfulfilled wish lists of their ancestors into electric light bulbs (which are also microphones). The dialogue extends into the audience when Chinner and Pill play an intimate Chinese Whispers game followed by a call and response scene (“Put your hand up if…”) warmly inviting us into the children’s world.

The audience is given lit candles to hold and extinguish at will to signal the end of the show. The piece could easily have been repeated or continued in a durational fashion as it employs no apparent dramatic score.

Babushka displays moments of wistful montage recalled and re-enacted with considerable skill but without analysis or attitude. I was left trying to open the next Babushka doll, wondering how each family history had affected the outlook of individual or community and how the experience of one generation might have influenced the next.

Parallelo Open Platform (POP), Babushka, Auditorium, Art Gallery of South Australia, North Terrace, Adelaide, May 25-29

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 10

© Sarah Neville; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

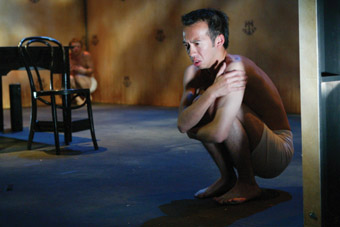

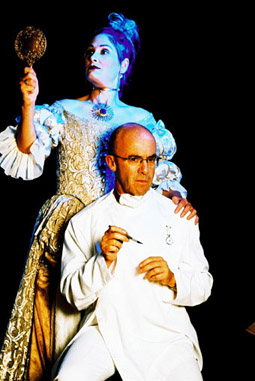

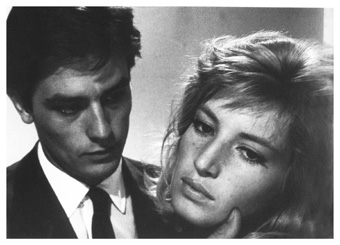

Cecil Parkee and Dim Sim, Karaoke Dreams

photo Heidrun Löhr

Cecil Parkee and Dim Sim, Karaoke Dreams

Walking into Bankstown District Sports Club, your body is instantly arrested by a dizzying sensory glare: vomit-motif carpet set against the trill of pokies running inane bleeps up and down the octave; coloured lights that flash, and lighter lights that pulse your brain and make the world seem incessantly, fluorescently candied. Young families, old codgers and stilettoed teenage girls gather for a cheap feed, a bit of a twinkle or a sly flirt. Everyone loves a club. What a scene. What a place for a show.

Contemporary performance in Sydney can get a little heady at times, which is why the ‘getting back to basics’ approach to theatrical exhibitionism offered by Urban Theatre Projects’ (UTP) latest community work Karaoke Dreams came as relief and pure pleasure. Set upon a faux fernery stage, the performers went about making a show of their showiness, one-upping us all in the stakes of watching and making performance. Inspired by the insidious talent quest/reality TV genre that rudely shoves unknown, untalented anybodies into our loungerooms every night, Karaoke Dreams takes the notion of talent and plays it against expectations. Who do we like? Who do we judge? Who’s gonna make it?

The tone of the work is playful in its surreptitious beginning. Chintzy jazz and lounge piano blend into Bingo numbers rattled off as the stage manager and gold-laméd competitors prance on and off stage. Occasional nods from half interested punters propped sideways suggest that this cheeky pre-show rendition of sports club life draws precariously close to the showman heritage of their local turf. Yet this performance is not about making farce out of popular entertainment, nor is it about the novelty of ‘performance’ encroaching on Karaoke territory. It is actually about using one form to reframe another, to expand the possibilities of performance and importantly, the people whom performance may or may not include.

A hostess with “the mostest” booms her introduction to the competitors who will stake out their fortunes on the grand stage of talent quest history. Backed by projected game cards detailing personal histories, they emerge ready to “do anything, or anyone, to win.” We meet a ventriloquist with a repertoire of classic vaudevillian gags, a fruit poet spouting lines of lyrical produce, a walking tree, a sequined tap dancer and some vocal balladeers. We hear heartfelt confessions from them too. One songster happily dreams of being a backup singer for the rest of her life. In a monotone, the Bingo lady pins personal facts to the numbers she reads: “For 5 years I’ve worked in this club, number 5. Ninety-two is the size of my bust, 92.” Her expert drollness is mirrored by a heckler standing dormant at the bar, animating himself only to jeer at the judges when they make their call.

As act follows act, the more interesting action revolves around the increasingly dirty competitiveness and botched romances between players. The Trivia Quizmaster has some recent love history with the hostess or the Bingo lady or both. The ventriloquist starts playing hide-and-seek with his puppet’s voice on the ceiling, the fruit poetry disintegrates and the MC and Trivia Quizmaster engage in a Sumo wrestling match to settle their scores. As the competition runs amok, with a mess of disillusioned dreams spilling out of the fernery, one wonders how the piece can salvage itself from complete disarray. But then, a pause. It’s time for Bingo.

Should I be embarrassed that I don’t actually know how to play Bingo? Given the classic prize of an enormous meat tray, I wasn’t sure I wanted to know, but the reprieve from the competition format and the return to an interplay between cast, club-goers and audience was welcome. So too was the finesse with which the wrap-up of the contest allowed for a few home truths about the making of the work to bleed through. Sucked into the cheap glitz of it all and mesmerised by the beautiful vocal talents of the cast, I found myself caught up in the stakes of the competition. Yet the players are very aware of the role they are inviting us to take, hissing at each other with derogatory taunts—even UTP gets stung for exploiting the cast’s talents to further their own agenda.

And yet it is obvious that these would-be wannabes are much more talented than any ‘real’ talent show would reveal. As a final pink-feathered peacock traipses on stage to sing a closing homage to Britney or Beyoncé, I sit back and enjoy the fun of a decidedly fake talent show. And there’s drink, cheap drink. What a place for a show.

Urban Theatre Projects, Karaoke Dreams; directors Katia Molino, Alicia Talbot, musical director Peter Kennard, video and animation Fadle El-Harris; Bankstown District Sports Club, Sydney, May 19-29

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 10

© Bryoni Trezise; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

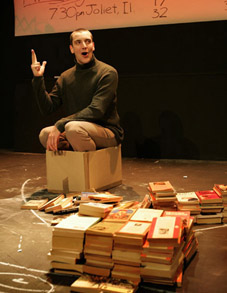

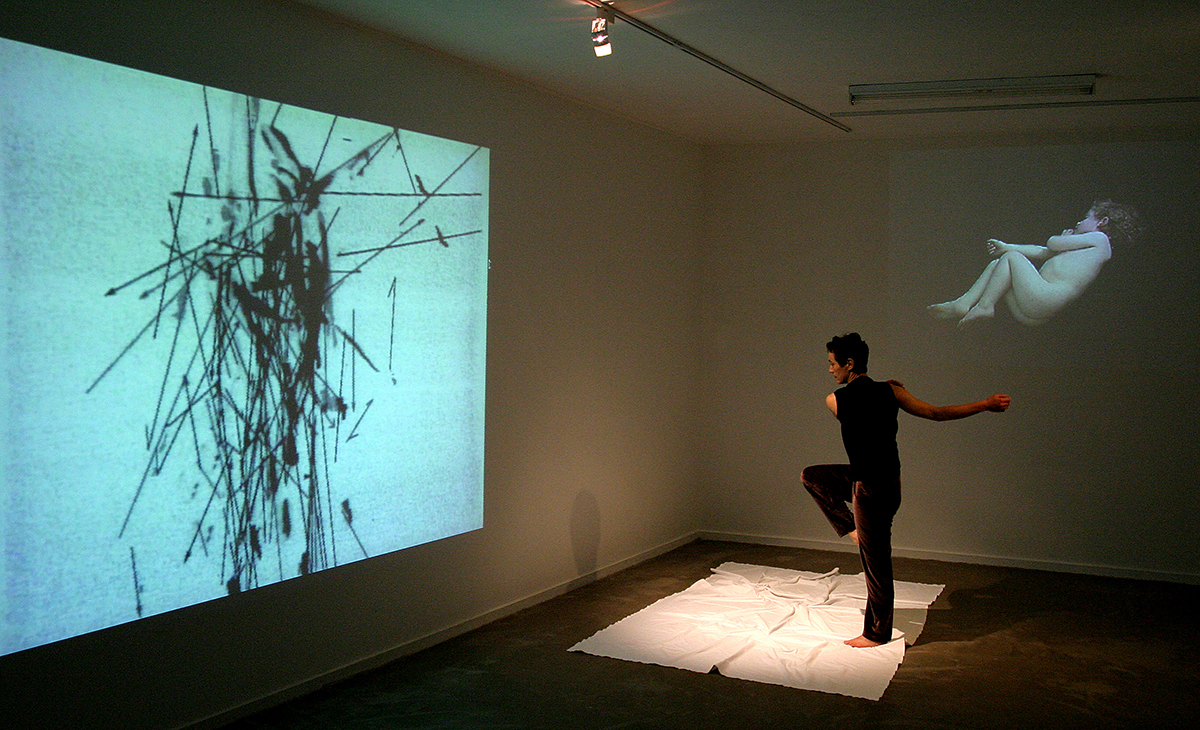

Gibson Nolte, Nocturne

photo Jon Green

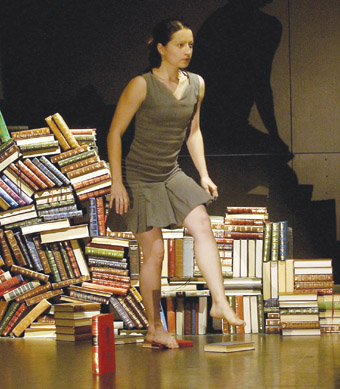

Gibson Nolte, Nocturne

It is easy to see why Steamwork’s Sally Richardson was keen to obtain the rights to Adam Rapp’s award-winning monologue Nocturne. In the words of the New York Times: “[Rapp is] a writer on the cusp.” Nocturne is a self-consciously literary script that strives for the original metaphor and the striking simile. It is also a well crafted and eloquent tale of tragedy, exile and overcoming.

In this recent production at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, American-born Gibson Nolte plays the son who has inadvertently brought tragedy upon his family. Nolte immerses himself fully in the demands of the 2 hour monologue and he is well supported by Andrew Lake’s simple yet effective design. Under Sally Richardson’s direction, Nolte offers the audience an intense and at times moving performance that strives to mesh psychological realism with the extended poetics of the text.

The opening line of Nocturne is the perfect narrative grief hook: “15 years ago I killed my sister.” The son writes the line across the back of the stage before reading the sentence out loud and then dissecting its various syntactic possibilities, none of which, we are to understand, can change the nature of the catastrophe that has occurred. The opening thus places writing and storytelling centrestage, only to signal its inadequacy and lack in relation to “the real.”

The opening line also establishes a relationship with the audience that is predicated on revelation and the uncovering of truth. Is this really murder? How was the girl killed? Why? We learn that the son was 17 at the time of his sister’s death, that it was an accident, that the brakes failed and that it ruined the lives of his mother and father. We also learn that at the time of re-telling, the son is a writer with a well-reviewed novel under his belt.

Nolte is rarely silent throughout the 2 hour show. I find myself thinking about much more than culpability and narrative drive. What kind of character speaks like this? What story does theatre tell itself to rationalise its peculiar behaviour? Why is the son telling us all this? Is this monologue a defence? A confession? Catharsis? A cover-up?

Nolte’s performance strives for an off-the-cuff quality, as if the character were composing his speech as he went along. In trying to naturalise the ‘writerly’ origins of this script (signalled then disavowed in the opening), Nocturne glosses over the fraught relationship between guilt and storytelling, trauma and repetition, and the ways in which grief is cauterised by the act of telling unreliable but necessary tales of overcoming.

Nocturne is ultimately not about trauma, repetition and storytelling: it is about how a boy overcomes tragedy to become a man and an artist. In this theatrical take on the Künstlerroman (the novel of the artist’s education), the death of his sister ultimately releases the writer-to-be from twin instruments of oppression: the study of piano and family obligations. Estranged from his family, he ekes out a meagre life working in a bookshop on New York’s Lower East Side. Forced to make do, he constructs his table and chairs from well-thumbed orange Penguin paperbacks that he reads voraciously. Literature literally furnishes him with a life. Nabokov, Updike, Hemingway…the list is erudite, if familiar. Nocturne is powerful and affecting theatre, but there remains something depressingly predictable in this modernist tale of masculine creativity.

In the final scenes, the son narrates his reluctant journey at the behest of his dying father back to the grim, cold Mid-West of his past. I realise that I do not like this son and that I do not completely believe the well-crafted story he tells himself and us. There is no rule that says I have to empathise with a character, but in this production I sense that it is important, and that there is little space for non-believers in the audience.

With the death of the father and the lack of narrative interest in the mother (she is in an asylum), the son is safe to claim what Nocturne sets up as psychological closure, but looks a lot like narrative expediency.

If this is realism, then how does it feel to have your identity as a writer dependent on the sacrificial death of an innocent? Here is a character who transforms trauma into speech, but at what cost? Must the family die so the writer may live?

“You see in 1967, while I was trying to take my first vacation, my mother killed herself.” This is the first line of Spalding Gray’s Monster in a Box. For Gray, who played on the edges of autobiography and performance, personal tragedy and loss were never easy to narrate and his story certainly did not obey the dictates of a happy ending.

But after all, that was life. This is realism.

Steamworks Arts Productions in association with B Sharp, Nocturne, writer Adam Rapp, director Sally Richardson, performer Gibson Nolte, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, June 9-27

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 12

© Josephine Wilson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Two days before the winter solstice a large black edged screen looms in front of a sandstone quarry. The trees are bare and a freezing wind buffets shoppers traversing Hobart’s Salamanca Square. Windows of a multi-storeyed apartment complex face a wall of shops and restaurants. In another time and context the square would be the site for political gatherings and revolution. Today it is the locale for is theatre’s U.T.E. 2.

Five artists arrive in a white 1977 HX ute: Scott Cotterell, Sarah Duffus, Cameron Deyell, Jen Cramer and Ryk Goddard. Their combined skills include dance, digital media art, performance, fashion design, installation, composition, sound, clowning and free form improvisation. For 5 days they sample and interact with the physical and social environment of Salamanca Square. In response to what is seen, heard, felt, discussed, dreamt, glimpsed or intuited, the U.T.E. group conceptualise and improvise a “Universal Theory of Everything.” Using diverse media, the artists process their materials in response to emergent themes. Ideas and insights combine and collide to create a free-form work which incorporates image, electro-sound-scores and sculptural installations leavened with excerpts of text. The result is passionate, unpredictable live art.

The back of the white ute, central to the production of U.T.E. 2, is a glorious installation in itself, carpeted and crammed with cameras, computers, sound and technical equipment and participating artists. Images of Salamanca Square are captured and projected from inside.

What fascinates about the U.T.E. 2 improvisation is the way unnoticed or unremarked upon elements of the Salamanca landscape are given back to the viewer. The intersecting mesh of the quarry’s perimeter fence provides an on-screen grid projection that is softened and hazy. Leafless trees backlit against the winter sky bring to mind a scene from a Paul Cox movie. Blue eyes on a female face dissolve to facelessness. The audience watch themselves watching.

Text developed in response to Salamanca Square is incorporated into the screened performance: Windows frame choices/ choices windows frame/ living vs lifestyle/ window frame choices. Performers assembling and reassembling white squares attached to a frame augment the inversion and double reading of the windows text.

The changing sculpture triggers fragments of questions: When do edges become a totality? What is the view between? Navigating the square, where does the line of vision fall? By rearranging the squares and clipping them to another part of the frame, the sculptors provide a shifting view of the square, echoing the projected text.

U.T.E. is a long term project, occurring twice a year for 3 years. It aims to thematically develop creative processes that can interact with artists or communities in diverse places and eventually become a tool for international collaborations.

is theatre ltd, U.T.E. (Universal Theory of Everything) 2, guest designer Greg Methé, technical support Ben Sibson; Salamanca Square, Hobart June 19

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 12

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

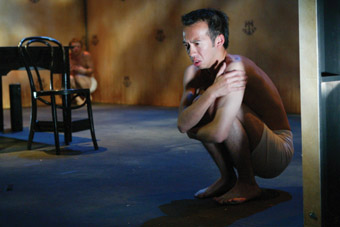

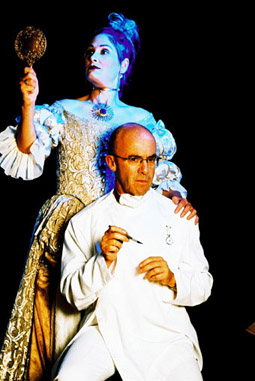

Stephen Whiley, Crispian Chan, Striptease

photo Bodhan Warchomij

Stephen Whiley, Crispian Chan, Striptease

It’s a mad, bad world all right, and yet here in Australia we’re living high on the hog (in a manner of speaking). So perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised about the current Perth-based resurgence of interest in Theatre of the Absurd. BSX-Theatre, the youth initiative of Black Swan Theatre Company, has just completed a double bill comprising Striptease by Polish playwright Slawomir Mrozek and Mountain Language by Harold Pinter. Prior to this, BSX director Matt Lutton directed Ionesco’s The Bald Prima Donna, while independent performer/director Marta Kaczmarek recently performed Beckett’s Happy Days at the Blue Room Theatre. She’s also planning a production of Ionesco’s The Chairs in 2005.

As anyone interested in performance will know, ‘Theatre of the Absurd’ was a term coined by critic Martin Esslin for the work of a number of playwrights mainly from the 1950s and 60s. Given John Howard’s nostalgia for that golden time of blue skies, white picket fences and happy families, it seems only fair that we also remember the other determining characteristics of the era: post-war trauma, refugees, McCarthyism, totalitarianism, cold war and the threat of nuclear annihilation. Paradise for some. A living hell for others.

Absurdist playwrights share the view that humankind inhabits a universe whose meaning is indecipherable. Human life is precarious, meaningless and without any kind of surety. We are perpetually bewildered, troubled and obscurely threatened. In formal terms, the Theatre of the Absurd was also a rebellion against conventional theatre. In fact it was anti-theatre: surreal, illogical, plotless and without dramatic conflict. The ultimate realism perhaps? In First World communities, we watch the horror of life in other places from the comfort of our living rooms. It’s a bit like going to the theatre, but what have we learned and how should we act?

In Striptease, 2 men arrive on stage as if hurled by a violent, unknown and unnameable force. They are wearing identical suits and ties and carrying matching brief cases. They don’t know why they’re here and don’t understand why they can’t leave. They don’t know their crime and no one will speak to them. Sound familiar?

What differentiates them is their respective responses to arbitrary detainment. Man 1 (Crispian Chan) is adamant, Buddhist-like in his refusal to act. He is determined to sit quietly and await his fate, no matter what the provocation. Man 2 (Stephen Whiley) is restless, aggressive. He wants to know his crime and confront his captors, whoever they might be. Each time he protests or attempts to leave, a giant mechanical hand enters and will not leave until a piece of clothing is sacrificed. Slowly, each man is divested of his clothing, until they are handcuffed together in their underwear. Simultaneously the walls draw closer and closer together, so that by the end of this short play, the almost naked, trembling protagonists are left with literally nowhere to go, no place to be and nothing to say.

Pinter’s Mountain Language was written in response to the conflict between the Kurds and the Turks in the late 80s. Once again we are confronted with troubling, horribly familiar images. The mountain people are no longer allowed to speak their language. Their world has been invaded and is under the control of an unnamed and brutal occupying force. In an almost black space fitfully illuminated by the glare of white searchlights, hooded and bound prisoners are menaced by large (actor) dogs. Protest seems futile. ‘Language’ is forbidden. Little more than a powerfully extended image, with a poignant but restrained sound design by Ashley Greig, Mountain Language painfully evokes our present time. There is no resolution and no happy ending.

Nineteen year old director Matthew Lutton and his young cast have created mesmerising theatre of great value. It’s just a pity it’s so goddamned relevant.

BSX-Theatre, Striptease, writer Slawomir Mrozek; Mountain Language, writer Harold Pinter; director Matthew Lutton; Dolphin Theatre, University of Western Australia, June 10-19

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 13

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Robyn Archer has done it yet again, created another unique festival program, richly themed, grippingly lateral, passionate and inclusive for a wide range of audiences. Best of all Archer’s choices reflect the state of the arts mid-decade: exploratory, innovative, hybrid and with a potent interplay of the local and the global. Archer celebrates the voice with mass yodelling singalongs, competitive karaoke, intensive workshops with some of the world’s most adventurous vocal virtuosi, new generation operas by Australians and others, sonically designed multimedia performances, song recitals, live poetry and classics from Mozart and Schubert sung live in interpretive dance scenarios from great choreographers.

As Archer puts it, her festival is about the voice “metaphorical and literal.” In Alladeen, The Builders Association (NY, see RT#57, p28) and motiroti (UK) collaborate on a sophisticated, multimedia response to the Aladdin tale in terms of the new economic colonisation that transforms Indians working in call centres into masters of vocal disguise. In Victoria’s (Belgium) üBUNG 6 children onstage watch 6 adults at a dinner party onscreen and create the vocal soundtrack for the film—charming at one level, says Archer of this drama of mimickry and socialisation, but disturbing at another.

There’s also a strong strand of puppetry vis a vis the voice in the festival. Ronnie Burkett (Canada), the tour-de-force puppeteer for adults manipulates and voices his many onstage charges in full view of the audience in Provenance, an art mystery about the history of a painting. South Africa’s astonishing Handspring Puppet Company directed by animation maestro William Kentridge present Monteverdi’s opera The Return of Ulysses in a contemporary setting and in collaboration with the Ricercar Consort. Each character is worked by both a puppeteer and a singer. Melbourne’s Aphids will present their miniature puppet plays, A Quarelling Pair, including one by the American writer Jane Bowles.

Operatic voices are explored through an onstage interplay with dancing bodies. In Mozart/Concert Arias 1992 the wonderful choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker with her company Rosas (Belgium), 3 sopranos, director Jean-Luc Ducourt and Alessandro de Marchi conducting the Australian Brandenberg Orchestra, entwine Mozart and dance in a widely acclaimed performance. De Keersmaeker herself will perform Once, a new solo meditation on American culture from the Civil War onwards to the music of Joan Baez’s In Concert Part 2 (1963). In another interplay of voice and body, with 3 dancers, a pianist and the acclaimed British baritone Simon Keenlyside, the great American choreographer Trisha Brown transforms Schubert’s Wintereisse song cycle into a visual drama, integrating the singer boldly and seamlessly into the dance. “Not a note is lost”, says Archer.

The festival offers some intriguing perspectives on opera and music theatre in the early 21st century. For younger audiences, Windmill Performing Arts, Opera Australia and MIAF have combined to premiere Midnite, based on Randolph Stow’s novel. It’s composed by Raffaelo Marcellino with Doug Macleod as librettist. In the long-awaited “opera in 4 orbits”, Cosmonaut, a doomed Russian astronaut communicates with an Australian woman while the USSR crumbles. Cosmonaut is by composer David Chesworth to a libretto by Tony MacGregor and premieres under the direction of David Pledger.

The Busker’s Opera is multimedia virtuoso Robert Lepage’s take on John Gay’s 18th century The Beggar’s Opera (Ex Machina, Canada). As in the original, popular tunes of the day are deployed, “from hard rock to klezmer, delta blues to show tunes, rat pack to Gay’s originals” in a timely tale about a busker destroyed by the “cultural industry, copyright laws and heroin.” Archer says this is high quality trash, with outrageous but miraculously engrossing singing and heaps of bad taste. Musiektheatre Transparent’s Men in Tribulation (Belgium) is a new opera by Eric Sleichim for counter tenor, narrator, saxophone quartet and electronics to a text by Jan Fabre inspired by Antonin Artaud’s time spent with the Tarahumara Indians in central Mexico. The great Vivian de Muynck (previously seen in Australia with Needcompany and the Wooster Group) performs with experimental vocalist Phil Minton.

There’s a lot more on the program. Ruby Hunter and Archie Roach collaborate with Paul Grabowsky and the Australian Art Orchestra on Kura Tungar-Songs for the River, a large-scale reworking of the engrossing, moving and sublimely orchestrated Ruby’s Story (see www.realtimearts.net). Japan’s Granular Synthesis appear in Modell 5, an extreme merging of sound and visual image as the projected head of performer Akemi Takeya is subjected to multiple transformations on 4 screens and in surround sound. Very loud, very subtle. The Singapore-Australia co-production Sandakan Threnody is a powerful account of the consequences of war crimes (see review of the Singapore Arts Festival premiere, p47). And The Audiotheque: Night Voices is a live to air broadcast for a very live audience of Radio National’s The Night Air at the National Gallery of Victoria.

If you want to lift your vocal game, Institute for the Living Voice, originally out of Belgium, is a unique 11-day offering for singers and others to work with some of the world’s most remarkable voices, including David Moss, director of the project. Or yodelling or karaoke might be more your thing. Whatever, the arts pilgrimage that once coursed its way to Adelaide will again this year head to Melbourne, to celebrate voice newly embodied in the works of De Keersmaeker, Kentridge, Lepage, Brown, Keenlyside, Burkett, Moss, de Muynck, Granular Synthesis, Chesworth, The Builders Association, Marcellino, Archie Roach & Ruby Hunter and many, many more. KG

Melbourne International Arts Festival, October 7-23, www.melbournefestival.com.au

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 14

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jonathan Nix, Hello

Australian animators are a hardy mob. Working in an industry that’s noticeably cramped, they are largely under resourced and mostly undervalued. I recently talked to a range of animators from around the country who have had one or 2 short films screened at festivals and asked whether their tertiary experience has helped jumpstart their careers.

I first looked to Queensland, where there are some fine animators making successful short films, including Andrew Silke (director with Dave Clayton, Cane Toad, 2002) and Mark Traynor (The Shapies children’s TV series, 2002). However, they’re not recent graduates, and according to Michael Viner of Brisbane’s animation and digital production studio Liquid Animation, there is no new crop of filmmakers coming up behind them. Viner claims the Queensland scene is “pretty dead”, despite burgeoning opportunities for animators in the games industry.

Similarly, Craig Kirkwood of the Tasmanian Screen Network (RT61, p20) warns against reading too much into the relocation of production house Blue Rocket: “They moved down here some years ago from Brisbane, and while they’ve created jobs and opportunities for quite a few animators, I don’t really think that’s necessarily a trend.”

The Melbourne International Animation Festival (MIAF, see p22) has a component entitled Australian Panorama and a commitment to showcasing current Australian animation. However, given Viner and Kirkwood’s remarks, it wasn’t really a surprise to discover that of the 11 films screened this year in the Australian section, 8 were made by graduates from Melbourne’s Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) and RMIT.

Festival director Malcolm Turner says the panorama was as representative as it could be: “The bottom line is that Melbourne is the mother lode. This year’s festival actually had a lower than normal percentage of Melbourne stuff because we pushed as hard as we could to include material from other places. It’s the same with festivals overseas—if an Australian film turns up in an international festival, it’s 80% likely to have come from Melbourne.”

Jonathan Nix had 2 films screening at MIAF. He graduated from RMIT’s Centre for Animation and Interactive Media (AIM) with a postgraduate degree in 2002, and is currently based in Sydney working on his next film for Cartwheel Partners. He made his first animation in high school, but said it was so appalling he didn’t animate for another 20 years. What lured him back? “It was a snap decision after returning from overseas”, he says. “I liked what I saw on the AIM website—their philosophy seemed to encourage individual expression—and the lecturers asked intelligent questions during the interview. A bit too intelligent—I didn’t understand some of them—but luckily they had a sense of humour as well.” Nix was used to working in isolation, but says his tutors encouraged him to relax and open up his work to outside influences. His award-winning short Hello (RT58, p21) was developed while at RMIT and Nix still considers AIM’s Jeremy Parker to be a mentor of sorts: Parker has edited 2 of Nix’s films.

Mark Ingram works as an assistant animator at the Disney Studios in Sydney. He graduated from the VCA School of Film and Television in 2002. He chose the school because of the calibre of former graduates: “Does the name Adam Elliot ring a bell?” Like Nix, Ingram was drawn to the course’s focus on individual expression: “The course promoted personal creative growth, as well as teaching animation in its entirety—script, music, editing and so on. I was amazed at what I was able to achieve in a single year.” As the program unfurled, he found his style “shifting dramatically from a focus on technique to story and character”, an important development as “the industry is very small and you really need to be a great storyteller or you won’t get far.” Ingram adds: “The lecturers’ wealth of knowledge was highly influential, opening up pathways and possibilities I’d never imagined before. My lecturer, Andi Spark, was my mentor—and in some ways, still is.”

Ingram was influenced by Disney cartoons and is understandably pleased to now be working for the studio. Ideally, he wants to take the next step and become a fully fledged Disney animator, but he sees his time at VCA as crucial in giving him his start: “My year at the VCA is the sole reason I’m now working in the industry. I’m sure I would have found my own way somehow, but it would have taken years of fumbling around. Studios, for the most part, are only really interested in seeing a show reel or proof that you are capable of doing the job with limited or no training on their part. University is the only place you can get the experience necessary to get a job in animation.”

Xavier Irvine, another recent graduate from VCA’s animation degree, concurs. He says of the second half of the course: “[It was]…structured like a real world production. We had to submit budgets and work to schedules—just like the film I’m working on now at 3D Films. Actually, I saw the whole program as being relevant to working in the industry.”

One of the few non-Melbourne animators screened at MIAF was Bill Chen, with Placement. Chen graduated from Sydney’s Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS) in 2002 and says the ratio of students to tutors there was around 3 to one, “which means I got to pick my tutors’ brains all day.” He adds that the course had a substantial vocational element: “Most tutors there are industry professionals, so you get to learn the industry standard. Although the qualification itself didn’t help me get a start in the industry, the work I produced during the course did, plus the contacts I made.”

Chen says AFTRS was realistic about the limited funding and job opportunities available once study had finished. Ingram got a similar heads-up from the VCA: “Right from the start we were informed, even warned, about the unsteady nature of the industry. It was a reality check I very much needed.” According to Nix AIM was equally up front about the students’ prospects, frequently inviting professionals to speak on the state of play and organising visits to animation companies and studios. The situation was made clear—sometimes too clear: “It was quite depressing, really. However, AIM seems to have a good percentage of ex-students working within the industry, which was encouraging.”

Could the courses be improved? “Yes—with more funding” was the unanimous response. Ingram explains: “We were working on such a tight budget that it often seemed impossible to get the job done. More time would have helped too—2 years instead of one. We could then have had more in-depth training in techniques and practical hands-on experience.” Irvine agrees: “More specific technical training was something I wished we had more of, but then again you walk out with 2 films at the end of the day. Too much focus on technical issues might well impede some of the current strengths.” Chen believes AFTRS needs “less screen studies and more practical work, as well as less [interventionist] departmental policies.”

For Nix, the AIM course needs improvement of a different kind. He observes: “Some films produced through other courses end up finished to film and are heavily promoted by the course itself…there needs to be the commitment [from AIM] to look beyond video in terms of the finished product.”

All the interviewees, however, were quick to state that the institutions are doing their utmost with limited resources, and all hope the Oscar success of Harvie Krumpet might help counter the ongoing Australian cultural cringe and lead to increased funding. Yet Ingram is not confident this will happen any time soon. Globally, he says, animators are suffering greatly: “We are in transition and confusion as we wait to see what 3D will do to the industry. On top of this, we are unfortunately at the mercy of the American industry. They’re in strife, therefore we’re in strife.”

Given the generally dire financial situation, I asked the group if a tertiary education was essential to make it in animation. “Not necessarily” replied Nix, “for me, though, I needed a concentrated environment and definite deadlines in order to progress.” Ingram categorically states: “Animation is an art, not a piece of paper that gets you a job. It’s talent and experience first and foremost. Tertiary courses simply provide the environment to gain that experience.”

Ultimately, in such a tough marketplace, Nix believes animators need more than just talent: “[You need]…a functioning business head—either split your own, or find someone else’s you can borrow now and again.” The example of the Adelaide-based People’s Republic of Animation is instructive in this regard. The collective comprises 6 members, all in the final stages of tertiary study. The group’s head, Sam White, didn’t study at the VCA or RMIT. In fact he didn’t even study animation. Instead, he is due to graduate this year from the University of South Australia with a Business (Commercial Law) degree. White says the course imparts “professionalism and the ability to understand the legal framework in which a company operates.” His business acumen helped the collective in their successful application for funding from the South Australian Film Corporation and the Australian Film Commission.

White, however, is a producer, not an animator. Are the days of animators beavering away in isolation and scrapping over scarce funds over? Perhaps collective models like the PRA are the solution, with divisions of labour ensuring animators concentrate on what they do best. As well as the increased focus on technical skills suggested by the interviewees, perhaps animation courses also need to teach more ‘real world’ business skills or facilitate contact between animators and producers trained in business.

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 17

© Simon Sellars; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Although Melbourne is currently dominating Australian animation, in recent years Western Australia’s Film and Television Institute (FTI) has been laying the educational ground work for a new wave of animators. The Centre for Advanced Digital Screen Animation (CADSA) was established in 2001 in conjunction with a broad coalition of industry partners. The Centre was “conceived and implemented as an animation production training incubator” in which students receive theoretical and technical training, as well as hands-on experience making animation productions. Several projects have already been completed by students at the Centre, including the film Desperado 2185 (Tim Beeson, 2003) and the game Children of Sivara. OnScreen will be watching future developments at CADSA with interest.

RT

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 17

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ivan Sen’s documentary Who was Evelyn Orcher? opens with a close-up of grief, a face caught in the remembrance of loss. He holds the shot longer than seems necessary or appropriate, not because he’s being unkind or vicarious (this is his own family he’s filming) but because he wants us to feel the full force of the pain.

As Sen stated in his introduction to the documentary at this year’s Sydney Film Festival, he is “sharing the grief of one Stolen Generation family.” It is an attempt to personalise the generalised term ‘Stolen Generation.’ He does this through the story of Evelyn Orcher, an older relative who was abducted from her family at 14 years of age and reunited with them 31 years later. In the aftermath of the reunion and Evelyn’s subsequent death, Sen listens to his family to find out who this person was and what it means to have something as precious as a life restored 3 decades after it was stolen.

The words of the remaining relatives, especially the women, make it clear that the grief doesn’t stop when the missing person is found. In fact it aggravates the pain and gives it fresh impetus.

Sen’s film is close-up and personal, the camera moving in and out of focus, shifting around to find new ways in. The shots taken while driving through the flat plains of western NSW—moving and yet immobile—recall his feature film Beneath Clouds (2001, RT48, p13). The vastness of the land provides a backdrop to the intricacies, interactions and ties of people’s lives in a place where they are lost and found. There’s no doubt Sen is there, intimately connected and involved, but he doesn’t personalise the story or make the film about his attempts to find out about Evelyn. Instead, he relies entirely on the spoken words of his family and Evelyn’s friends.

Likewise, he refuses to provide the type of narrative usually supplied from a privileged position by the documentary maker constructing a ‘complete’ picture strung together from people’s testimonies and carefully researched ‘facts.’ There is no official, authoritative version here of what happened to Evelyn or who she was. That’s not to say that such a narrative could not be constructed if necessary; there are glimpses of photographs and official-looking documents. But by denying an ‘authorised’ account, the film refuses to legitimise any narrative that purports to say what really happened. In the end, such a version of events cannot provide consolation for the pain of the Stolen Generations. Such trauma is not easily assuaged. The life in question can never be restored.

Instead of filling in blanks, the film leaves unanswered questions and loose ends. Why did Evelyn end up living the life she did? Who is responsible? That’s not really what this film is seeking to resolve: there is no satisfactory answer to the question “Who was Evelyn Orcher?”, just a few snaps, scraps, and raw memories. Evelyn’s painful, fragmented story remains where it should—in the minds and voices of those who cared for her most, not just her family but also the people who lived with her from day to day.

Personal documentary filmmaking was the topic of a forum held during the festival looking at why the ‘I’ of the beholder has become so prevalent in the form. Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock were cited as examples of filmmakers who, in expressing a viewpoint, become the subject of the film. Who was Evelyn Orcher? is different, an example of a personal film in which the ‘I’ is present but dispersed, manifesting itself through its relation to others.

Filmmakers Tahir Cambis and Helen Newman were part of the documentary forum, and their film Anthem screened at the festival as a work-in-progress. Both of them appear in front of the camera in the course of a film that is a personal odyssey through the events of the past few years, starting with the Kosovo refugees and continuing through 9/11, Tampa, Afghanistan, Iraq and the whole ‘War on Terror’ scenario. It is quite a jolt to revisit so many recent events and realise how far the social and political lexicon has shifted in a few short years.

Covering so much ground, Anthem is profligate in its use of material. Half a dozen potential storylines are opened up but never fully explored in the ceaseless movement from place to place. This is defiantly non-mainstream, eschewing any pretence of balance, impartiality or a ‘neutral’ territory from which to observe events.

The film’s best moments are the unexpected encounters—Ruddock being patronising at a public meeting, Howard looking shifty at a memorial service—that slip beneath the radar of daily media representations. The footage of protest actions at various detention centres is similarly revealing. Other parts of the film are less well integrated: for instance, the plight of an Iraqi family in detention who are subsequently returned to Iraq gets a bit lost in the mix. We’re not given much of a chance to become intimate with these people, which may be because Cambis and Newman are not solely focussed on making the type of documentary that attempts to humanise a subject, but the refugees are never really allowed to escape their status as victims of circumstance and politics.

Anthem is all about the buzz, the outrage, the exhilaration of events as they unfold. At one point, Cambis is filmed moodily standing on a pier, contemplating leaving for Afghanistan in the morning because “it might be interesting.” As a viewer, you wanted to scream “No! Don’t go!” Too late. Next moment we’re off on a race-around-the-world excursion, a backpackers-in-hell journey with bouncy taxi rides and late night drinking sessions. The “I wanted to find out what it was really like” motivation seems worthwhile but remains unresolved. Documentaries that try to get inside another culture from the outside require time, but Anthem doesn’t have that luxury.

For a personal record of contemporary events, Anthem comes across as strangely impersonal. We never really know these people, but then maybe circumstances don’t permit too much introspection. The filmmakers are drawn into events as they occur but reveal little about what the journey means to them as individuals. That’s not their project. Like Sen, Cambis and Newman realise the film is not about them or their story. But it is equally hard to determine the significance of parts of Anthem, apart from the fact that the filmmakers are there. Perhaps in a climate of such accelerated and radical change, simply bearing witness is one of the most important things a documentary maker can do.

–

Who Was Evelyn Orcher?, writer/director Ivan Sen, producers Ivan Sen, David Jowsey, 2004; Anthem, writers/directors Tahir Cambis, Helen Newman, producer Ross Hutchens, 2004; 51st Sydney Film Festival, State Theatre, June 11-26

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 18

© Simon Enticknap; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

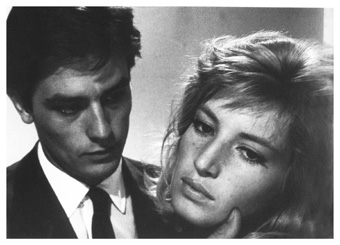

Sam Worthington, Abbie Cornish, Somersault

The first thing that strikes you about a Cate Shortland film is just how much meaning is conveyed by purely visual means. In marked contrast to the dialogue-driven nature of most Australian dramas, where the image all too frequently serves to simply reify what is being said, Shortland’s work is characterised by striking compositions, textures and colours, moments of narrative drift and countless temporal ellipses that leave everything to the imagination. Although Somersault is Shortland’s first feature, it represents the fruition of a style developed across 4 short films made over nearly a decade.

Somersault, premiering at the 2004 Sydney Film Festival, focuses on a troubled teenage girl called Heidi (Abbie Cornish), caught in the transition from childhood to adulthood. Early in the film, an incident involving her mother’s boyfriend propels her out of the family home to Jindabyne in the Snowy Mountains. Forced to make her own way, she strikes up a relationship with a local young man, Joe (Sam Worthington), and the body of the film traces their largely unsuccessful attempts to understand their budding emotions and desire for each other.

Superficially, Somersault is a study of alienation. Heidi escapes to Jindabyne upon losing the trust of her emotionally distant mother, but despite a naive openness that is sometimes painful to watch, she is unable to form lasting bonds with anyone in the town. A similar sense of isolation characterises all Shortland’s films. Joy (2000), her last short before Somersault and made while studying at AFTRS, portrays a day in the life of a young girl who inoculates herself against feeling by plunging into a haze of alcohol and frantic activity. The middle-aged central character of Pentuphouse (1998) risks her singing career and physical safety to be with her young lover, only to realise he will never be able give her the mutually fulfilling relationship she craves. Shortland’s most accomplished short, Flower Girl (1999, RT35, p13), focuses on a young Japanese tourist living in Bondi. He remains detached from his surrounds and unable to express his desire for his flatmate Hana, except through obsessively videotaping her.

Shortland’s characters are estranged from each other and the wider society in which they live, but what makes her cinema so resonant is their constant, desperate and often painful struggle to transcend their isolation and find ways of connecting in a world where traditional couplings and familial formations have ceased to be meaningful. The question at the heart of Shortland’s cinema is how to be in the world and with each other when established emotional and social structures no longer seem valid.

This longing for connection is played out in Somersault through the extraordinary lead performances of Abbie Cornish and Sam Worthington. In an interview with RealTime, Shortland explained that she engaged the actors in a 3-week rehearsal period prior to shooting in order to attain the restraint and subtlety evident in the finished film. Both actors embody the psychological fragility of people in their late teens and early twenties learning who they are and where they fit in the world. Cornish’s portrayal of Heidi conveys all the rawness of adolescent sexual and romantic awakening. Worthington exudes a tightly bound energy in the abrupt, awkward and angular movements with which he plays Joe, suggesting a repressed longing to embrace the world and escape the narrow confines of the town.

Joe’s reticence reflects an ambivalent relationship to language that runs throughout Shortland’s body of work, where words often block communication as much as they facilitate it. This thematic plays out explicitly in Joy, with phrases from standard parental lectures scrolling across the screen as the main character engages in a spree of shoplifting, fistfights and chance sexual encounters. These well worn adages highlight the way the language of cliché frequently functions as a substitute for real communication between parents and children. Similarly, in Somersault Heidi resorts to formulaic romantic phrases to express a very genuine need for support and validation, plaintively asking an incredulous Joe if he loves her after they have spent just a few nights together.

This ambivalence vis-à-vis language crucially informs Shortland’s emphasis on the visual. Over the course of making Flower Girl, Joy and Somersault, Shortland has developed a close working relationship with cinematographer Robert Humphreys (RT50, p23). Shortland explains that their expressive use of colour has been influenced by American photographers such as Nan Goldin and Todd Hido, and cinematographer Christopher Doyle, particularly his work with Hong Kong director Wong Kar-Wai. Like Doyle, Humphreys’ expressionistic style never descends into pure abstraction, instead relying on a heightened sense of colour drawn from the film’s environment. The characters in Somersault live in a world of freezer-cold blues, evoking the crisp, frost laden air of the Snowy Mountains winter setting. Strident splashes of red stand out against the wash of blues that constantly threaten to overwhelm them. The colour scheme reflects the mental state of characters living in an emotionally ossified world, caught between passion and fear, distance and warmth, fear and desire.

The meandering pace and recurring moments of narrative drift allow the audience to sink into the mood evoked by Somersault’s colour palette. The film is littered with poignant, incidental moments of everyday life that add nothing to the plot, but convey everything about the sensibility of the central character. For all her immaturity, Heidi is able to see the transient beauty of the world around her. Shortland draws us into this awareness, taking the time to picture Heidi drinking gracefully from a backlit water fountain, scattering a pile of dried crumbled leaves off a balcony, and watching a small boy jump on a trampoline.

“What I really love is beautiful things”, Shortland says, and perhaps ultimately this is the essence of her cinema. As a director and scriptwriter, she has the ability to find beauty in the prosaic poetry of everyday objects. Underpinning this sense of wonder is an enduring sense of hope born of our desire to be at one with each other and our surrounds, even if this desire is constantly thwarted.

Somersault, writer-director Cate Shortland, producer Anthony Anderson; performers Abbie Cornish, Sam Worthington; Hopscotch, 2004, various cinemas nationally from September 16

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 19

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sejong Park's Birthday Boy

Korea, 1951. A young boy plays amongst the ruins of his country’s civil war. The landscape is a drab brown, devoid of life. The boy stages a game of soldiers in the streets of his dilapidated village, childishly re-enacting the conflict that has left its marks all around him. He returns home to find his father’s possessions neatly parcelled and sitting on the doorstep. Unaware of the significance of such a ‘present’, he slings his father’s dog tags around his neck and marches up and down outside the house. That night he plays sleepily with his toys as his mother arrives home. Her cheerful greeting indicates her ignorance of the news that awaits her.

This simple tale is the basis of Birthday Boy, a short in the anime style made by Sejong Park while studying at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School. In 9 minutes, Park’s work manages to convey the twofold horror of war.

Firstly, he shows us how conflict seeps into every aspect of people’s lives. The child of Birthday Boy is not only surrounded by the detritus of war, it permeates every aspect of his life and behaviour, down to the toys he plays with and the games he enacts. He runs among abandoned military hardware littering the landscape. A train passes, laden with tanks. The endless procession of silhouetted man-made monsters starkly illustrates the faceless nature of modern, mechanised warfare, recalling a similar scene from Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence (1963). Ironically, the boy uses the passing train to crush pieces of scrap metal to use in his collection of homemade toys, all of them replicas of the war machines from which the scrap metal comes.

The second, more unsettling experience of living in a war zone evoked by Birthday Boy is that of absence. The town is unnervingly deserted. There are no other children and none of the bustle of urban life. The boy’s home is also empty. His mother works and his father has been taken by the army. The tragedy is that the child has no idea that the loss of his father is permanent. He plays on, oblivious to the bereavement that will shape the rest of his life.

Birthday Boy movingly sketches the kind of tiny incident that occurs countless times in any armed conflict. In doing so, Park’s film reminds us of what politicians and generals would have us forget: that it is not the grand battles and levelled cities that represent the true horror of war, but the accumulation of innumerable individual absences in the lives of those left living. These are the holes that remain long after the material damage has faded.

Birthday Boy won the Yoram Gross Animation Award at this year’s Dendy Awards for Short Films, 51st Sydney Film Festival.

Birthday Boy, writer/director Sejong Park, producer Andrew Gregory

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 21

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Carl Stevenson's Contamination

An important part of a burgeoning animation career is the exploratory or experimental phase. The results can be rough, brilliant or both. This year’s Melbourne International Animation Festival (MIAF) suggested that, with few exceptions, Australian animation is still at an exploratory stage. The program featured an eclectic program of student films, music videos, documentaries, Eastern European classics and the latest work from veterans such as Phil Mulloy. The emphasis on the richness of Russian and Estonian films highlighted the shortcomings of works from other countries.

The festival opened with a showcase of early Russian films demonstrating what makes for terrific animation: deeply textured plots, inventive characterisation and satirical twists. It was the perfect way to start MIAF—an example of what can be achieved with original ideas even on a slender budget. The Estonian Panorama proved another highlight, despite that country’s small industry of only 2 animation studios. Priit Tender’s masterful Gravitation centred on a surreal road trip, playing with conventional perceptions of story and of the film frame itself. Tender’s Mont Blanc overwhelmed with vivid images of an insurmountable mountain of suitcases, ominous ravens and menacing life-size pliers chasing the protagonist along a train of faceless workers. Much of the beauty of the Estonian films lies in what is not overtly stated, leaving interpretation wide open and creating an atmosphere of weird splendour without compromising the narrative. 3D technology is used minimally to enhance the animation rather than demanding to be noticed for its own sake.

The Priit Parn Retrospective showed the Estonian filmmaker to be a master of the form. The Night of the Carrots explored, via a labyrinthine hotel, our obsession with celebrity and the fear of computers taking over everyday life. The closing scene, in which evil rabbits perform voodoo on their carrots to control the world, was a festival highlight!

Films displaying the level of complexity evident in the Estonian works can only be achieved with sustained development involving government or private backing, something generally lacking in the Australian context. Of the local films, the widely discussed Harvie Krumpet (Adam Elliot, RT57, p19) sustained its story and clever characterisation over its half hour length, and Jonathan Nix did in Hello (RT58, p22) what few other animators are prepared to do, allowing the mood and theme of the soundtrack to lead the story. Generally, however, the offerings of the Australian Panorama came across as simplistic. The constant and gratuitous use of 3D computer animation showed that no amount of money spent on technique can make up for an ordinary script. Flat by Sebastian Danta was promising, with a scratchy illustrative approach and entertaining peek into the lives of flat-dwellers, but the computer technology applied to eyeballs and exteriors served merely to detract from any stylistic cohesion. Placement by Bill Chen was a wonderful futuristic story about human cloning, combining animation seamlessly with live action. But only Fog Eyes by Hamish Koci pointed towards a whole new strain of contemporary Australian animation being done with Flash.

A mix of media characterised the output of many films in the International Program. It’s Like That by the Southern Ladies Animation Group from Melbourne deservedly won the prize for best Australian animation. Using real-life recordings of refugee children in detention, the group deftly combined stop-motion knitted characters, Flash animation and cell drawings to create a deeply moving film about life behind barbed wire. Contamination (Carl Stevenson) created an eerie, unsettling atmosphere by merging animals with human parts and vice-versa. The Dave Brubeck soundtrack and frenzied squiggles of Cameras Take Five (Steven Woloshen) could have been created by the Canandian master Norman McLaren himself. I was pleased to see that an elemental technique like scratch-on-film could still get an enthusiastic reaction from the audience.

With only 6 days of screenings, it would be difficult for MIAF to give a total snapshot of current world animation, however the dearth of Asian content was a glaring oversight that many patrons commented upon. The main impression left by the festival was the disparity in quality between the Australian and international programs. Are we still at an exploratory stage? Is the problem a lack of funding, or do we need to direct our resources in different ways? Although the local offerings at MIAF were uneven, films such as Hello and It’s Like That indicate the immense, if largely unrealised potential of Australian animation.

Melbourne International Animation Festival 2004, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, June 22-27

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 22

© Rebecca L. Stewart; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

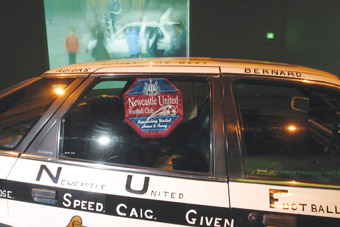

Paulo Alberton, Going to the Dogs

This year ScreenWest and the WA Film and Television Institute (FTI) presented a special showcase of emerging WA talent at the 2004 Revelation Perth International Film Festival. The Get Your Shorts On program contained 9 short narrative films in all, including drama, comedy and animation.

By far the most impressive was Victim, directed by Corrie Jones and produced by Amy Lou Taylor. The work embraced the short film form as integral to its narrative strategy. Based on a spoken poem by Nicole Blackman, Victim creates a dark and unsettling journey for the viewer, beginning with a woman locked in the boot of a car and progressing inexorably in a downward spiral. The slow measure of the hypnotic stream-of-consciousness voice-over (despite the annoyingly Americanised accent) maps a juxtaposition of images. Memories of life and loved ones filter through a bleak landscape of gender violence and the stark, brutal reality of the victim’s bound and imprisoned body. The psychological impact of this film lies in the fragmentary glimpses of interrupted vitality and the mental struggle for escape. This is a fine and polished piece of filmmaking, which has also recently won honours at the St Kilda Film Festival (see p25).

The surprise package of the selection was satirical mockumentary Going to the Dogs, written and directed by Paulo Alberton and co-produced with Rachel Way. This curious film begins with a breezy magazine-show tone, the narrator offering a tour of Cottesloe Beach and the culture of prestige pooches that features on the promenade. At first the film appears inanely preoccupied with this little subculture of affluence, but it reveals a clever commentary on multiculturalism and immigration within its examination of exotic dog ownership and the disparities between human deprivation and over-indulged pets. The mixture of animation and real footage is assembled with flair and the overall effect is genuinely funny in a fresh and playful way, with the social critique handled well.

Other comedy offerings also proved enjoyable. Renee Webster’s Scoff is an amusing tale of sensuality and desire. A young female cook on an isolated outback station transcends her binge cake-eating habits when she discovers the erotic possibilities of the showerhead spray, all the while voyeuristically observed by the team of 4 male station hands. Here a simple narrative premise is rendered with a fluid technique and solid performances.

The Olympiads Lounge (writer/director Pierce Davison) was another animated mockumentary, in which various gods and demi-gods from Greek mythology become hopeful stand-up acts in a comedy club. The mis-adventures of these unlikely contenders are well animated in a droll satire of the ‘behind the scenes’ documentary form.

The series of 5 one-minute animations comprising Suicidal Balloon (writer/director Randall Lynton) offered a set of kooky scenarios in which various precarious situations become chaotic as the dreaded balloon flies in, smiling broadly before exploding. The basic silliness of this narrative premise somehow works, particularly when all 5 one-minute pieces are screened in a row.

The remaining dramatic short films in this selection proved to be a mixed offering, with fundamental narrative and formal problems limiting their effectiveness. To hold a viewer in the time and space of a short film, all elements need to come together with a transformative magic, so that the whole becomes more than the sum of its parts.

The Cherry Orchard (director Elissa Down) presents a Magic Realist tale in which a woman’s fertility and fervent desire to create a hybrid cherry plant results in a strange crossover with her gynaecology. While offering some beautifully composed shots, the end result was undermined by the period setting and epic time-scale of the narrative, combined with stilted performances and the stiff realism of the film’s narrative technique.

Julius Avery’s Little Man gives the viewer a glimpse into the harsh social realities of a little boy whose dysfunctional home environment becomes shrouded in tragedy. Here atmosphere and technical deftness are burdened by a heavy-handed thematic treatment and over-determined narrative.

Waiting for Naval Base Lily (writer/director Zak Hilditch) presents an older man in a sterile motel room confronted by the likeness of a young and inexperienced prostitute to his daughter. A bright and saturated use of exterior light gives this piece a stark visual appeal, yet the narrative is awkwardly conveyed through dialogue and characterisation that frustrates the viewer’s ability to inhabit this fictional world.

The challenges of dramatic narratives highlighted by these films provide important lessons for aspiring filmmakers. Narrative form must be seriously addressed so that films can achieve an internal coherence and provide a rewarding journey for the viewer. Nevertheless, for the best of the short films in the Get Your Shorts On program, Revelation is to be congratulated for its admirable commitment to fostering local screen culture.

Get Your Shorts On, 7th Revelation Perth International Film Festival, Luna Cinema, Perth, July 8

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 22-

© Felena Alach; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

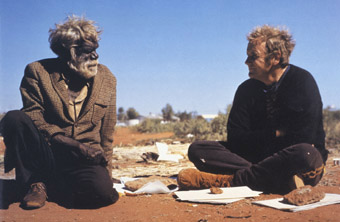

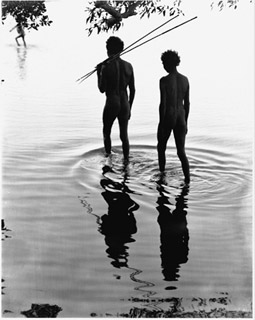

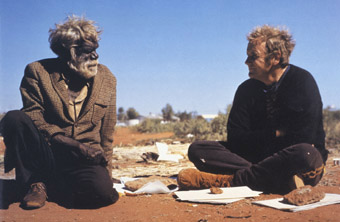

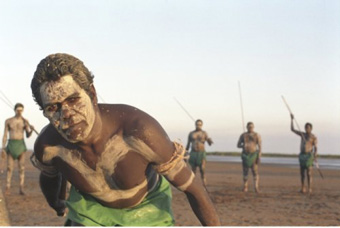

Tribal elder Old Tom Onion and Geoff Bardon in 1971, Mr Patterns

photo Allan Scott, courtesy the Bardon family

Tribal elder Old Tom Onion and Geoff Bardon in 1971, Mr Patterns

The 4 new Australian documentaries screened at this year’s Message Sticks Film Festival were all about giving voice to the silenced, either through reclaiming the past or giving space to contemporary voices generally excluded from mainstream public discourse.

Opening the festival was Ivan Sen’s The Dreamers, revolving around interviews with 3 young Aboriginal professionals: a singer, a soccer player and a champion surfer. Shot on video in hand-held style, Sen focuses resolutely on his subject’s faces as they relate their dreams and hopes for the future. There is no attempt to analyse or even portray these young people’s social or familial contexts. Instead Sen constructs 3 impressionistic character studies, his intimate framing and constant cross-cutting between interviewees suggesting the uncertain nature of their futures and the intensity of their desire to succeed.

The Dreamers furthers Sen’s reputation as a chronicler of young Indigenous Australians, begun with the short drama Tears (1998) and the feature-length Beneath Clouds (2001). Sen deals with the complexities of identity throughout his work, avoiding one-dimensional notions of its construction. The Dreamers conveys something of the character and hopes of 3 young Australians whose Aboriginality is integral to their identities, rather than being imposed by those around them.

Beck Cole’s Wirriya: small boy follows a few days in the life of Ricco, an 8 year old child living with his foster mother in Hidden Valley, an Aboriginal community on the outskirts of Alice Springs. Cole’s simple style allows Ricco to narrate his own story, although her camera remains a detached observer that sometimes contradicts him: “I’m not naughty”, he informs us at one point, after we’ve seen him acting boisterously in class and being scolded by a teacher at the local pool. At the same time, Cole’s observational approach and interactions with the boy bring out Ricco’s charm, bubbling energy and fierce intelligence.

Wirriya: small boy doesn’t shy away from showing the social problems that beset many Aboriginal communities. Ricco’s mother is the victim of domestic violence and despite her absence from the film and Ricco’s daily life, we get a definite sense of a troubled relationship between mother and son. At one point, Ricco and several of his step-siblings play truant from school and their foster mother freely admits her inability to stop them. Later, another small girl joins Ricco’s already crowded household due to parental ill health at home.

Despite the problems in Ricco’s life and community, the overall impression left by Wirriya: small boy is one of warmth, with Ricco’s foster mother lovingly presiding over the children in her care. At one point she relates Ricco’s promise to her: “I’m gonna work and I’m gonna look after you.” She smiles affectionately, but her nervous laugh belies her awareness of the obstacles that will confront him as he gets older.

In contrast to The Dreamers and Wirriya: small boy, Rosalie’s Journey and Mr Patterns delve into the past. Rosalie’s Journey provides a textbook example of how documentaries can reclaim and rewrite historical narratives. It tells the story of Rosalie Kunoth Monks, primarily known as the young woman selected by director Charles Chauvel to play Jedda in the eponymously named film of 1955. Through a contemporary voice-over, Monks recalls her life growing up at Saint Mary’s Boarding School in Alice Springs and Chauvel’s visit to the school looking for an Indigenous girl to star in his film. She recounts without bitterness his utter insensitivity to Aboriginal lore during the shoot. Monks was forbidden to look strange men in the eye, yet she was made to act as a love interest and object of lust for her co-star Robert Tudawali, a man she had never met prior to production.

Rosalie’s Journey fulfils the important task of relating the making of Jedda from the viewpoint of one of the film’s Indigenous stars, but what is most striking is how minor the entire episode has been in Monks’ life. She views her present role as a mother and language teacher as far more important to her sense of identity than her brief stint of screen acting in the 1950s. Director Warwick Thornton explores the way personal and historical narratives intersect and diverge, revealing how an individual’s identity as a historical figure can live on quite independently of the actual person and the direction their later life takes.

Unlike Rosalie Monks’ brief experience of fame, the life of Geoff Bardon was crucially determined, and ultimately destroyed, by the historical episode examined in Mr Patterns. Through a skilful blend of archival footage, old and contemporary interviews and expressive passages of time-lapse cinematography, director Catriona McKenzie tells the story of Bardon’s involvement in the Papunya Tula Art movement. Posted as a teacher to the Papunya Aboriginal settlement in the Western Desert in the early 1970s, Bardon displayed ground-breaking cultural sensitivity in his teaching methods, employing a translator to teach the children in their own language and encouraging them to express their cultural heritage through their art. This led to contact with tribal elders who Bardon encouraged to paint ancestral dreamings in acrylics. Bardon helped the elders sell their works, bringing income into the community and revitalising their cultural traditions. However, the mild-mannered teacher was ill prepared for the ruthless and unscrupulous nature of the art market and the backlash his actions generated in the education bureaucracy. He was eventually driven from Papunya suffering a nervous breakdown. Back in Sydney he was admitted to Chelmsford Hospital and endured Harry Bailey’s notorious deep sleep therapy, a form of ‘treatment’ for depression that left dozens dead and many others, including Bardon, physically incapacitated for life.

Unfortunately most of the Papunya elders involved in the story have passed away, so by necessity McKenzie relies largely on white interviewees. She talks to the school principal from Bardon’s early time at Papunya, an Indigenous woman who was taught by Bardon as a child, several of Bardon’s friends and Bardon himself. The love and affection all the interviewees feel for the teacher emanates from the screen.

Bardon himself appears as a hunched, trembling figure, a sharp contrast to the smiling, open young man we see in footage from the early 70s. The difference in his appearance poignantly brings home the extent to which Bardon’s experiences at Papunya and subsequent treatment at Chelmsford physically destroyed him. He died in May 2003, shortly after his interview for the film was completed.

Mr Patterns hints at the enormous cultural potential that exists if non-Indigenous Australia were prepared to open itself to Indigenous ways of thinking. The film also demonstrates how fragile this sense of possibility will always be when much of white Australia remains utterly oblivious or hostile to Indigenous culture, at best viewing it as something to be financially exploited.

The documentaries at this year’s Message Sticks Film Festival brought the stories of marginalised people to the screen and rewrote old tales from new perspectives. Curators Rachel Perkins and Darren Dale pulled off the difficult task of presenting a program of distinctly Indigenous films that retained a sense of Aboriginal culture in all its fluid, porous and varying forms.

–

2004 Message Sticks Film Festival, curators Rachel Perkins and Darren Dale, Playhouse, Sydney Opera House, June 11-13.

Mr Patterns can be purchased from Film Australia: sales@filmaust.com.au

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 23

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Diegesis is the premier showcase for film, video, photography and digital media works produced by Australian school students. Ideal for those studying design, drama and media studies, Diegesis aims to challenge young audiences through exhibitions, screenings, classes, career forums and industry seminars. Now in its tenth year, the event is hosted by Melbourne’s Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI).

The Diegesis screenings include a season exploring animation in all its forms through the work of some of Australia’s most innovative animators. It also includes a showcase of videos and interactive media works by primary and secondary school students from around the country. The Diegesis Screen Awards will see a prize of $5,000 in computer equipment go to the winning school. Additionally, a trophy will go to the winner of the Diegesis Photography Award, selected from approximately 140 student works exhibited at ACMI.

A series of forums will give students invaluable insight into arts and media-based careers. Game Loading will feature professionals from the rapidly expanding gaming industry, while in A Life in Pictures professional photographers host a series of sessions providing a comprehensive picture of photojournalism. In a masterclass held in the ACMI Digital Studio, photographer Brett McLennan will instruct students in the translation of traditional photographic practices into the digital domain.

With thousands of student and teacher participants since 1994, Diegesis has become a vital part of Australia’s screen educational landscape. RT

Diegesis, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Melbourne, Sept 3-8

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 pg. 24

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Garth Davis' Alice

In a typically pithy speech marking the commencement of this year’s St Kilda Film Festival, director Paul Harris noted the serious, even confrontational nature of many of the films in the program. He remarked that the opening night session reflected the provocative nature of the material many short filmmakers had elected to focus on.

Of the 7 films on offer, comedy and drama were evenly represented, with Ash Wednesday (Jason Tolsher, 2003), The Paddock (Peter Carstairs, 2003) and Alice (Garth Davis, 2003) tackling the grim topics of fratricide, rural isolation and the trauma of stillbirth. While Ash Wednesday suffered from an overly histrionic treatment of the family melodrama, The Paddock and Alice impressed with more considered approaches to their respective subjects.

These films flagged the uncompromising nature of many of the dramas featured in the festival, with topics ranging from pedophilia to suicide. But the opening night session was also instructive in another respect. It featured 3 films that focused on children—Clutch (Jackie Schultz, 2003), Alice and Marco Solo (Adrian Bosich, 2003)—establishing a recurring theme in the overall program. Youth-centered scenarios were conspicuous across all genres and formats including comedy, drama and documentary, and were equally well represented in the festival awards. Of the 150 films that screened at St Kilda, the most inspired were the short dramas that combined a focus on young lead characters with the sort of provocative subject matter Harris alluded to in his introductory comments.

I was less enamoured than the judges with 2 films that featured prominently in the festival awards: Martha’s New Coat (Rachel Ward, 2003) and And One Step Back (Mark Robinson, 2003). While both were undeniably well crafted, with strong performances from their youthful leads, neither tackled the dysfunctional family scenario with particular originality. There was a certain sameness to these polished, child-centered melodramas, to the point where both films featured half-sisters dealing with unreliable mothers and absent fathers.

Two films focusing on young boys, Green Eyes (Diana Leach, 2003) and Ice-Cream Hands (Gavin Youngs, 2002), made a much more powerful impact. The former is a stylistically sophisticated study in sibling rivalry. Leach initially establishes a fairytale feel to her period piece featuring a family who live in a lighthouse. But as the young son’s resentment of his baby sister intensifies, Cordelia Beresford’s atmospheric cinematography gives the film an increasingly surreal and sinister quality.