Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Morton Feldman’s music owes much to John Cage, who in turn owes much to Erik Satie. Feldman wrote For John Cage, for violin and piano, for his friend and mentor in 1982, a year after his extraordinary Triadic Memories for piano. Feldman’s later works tend be long, and For John Cage is well over an hour. They are also intensively notated-every detail of the music is exactly prescribed, including some wavering microtones for the violin, making them doubly challenging for the performer. There are many threads for the listener to unravel—structural form and detail and their development, nuances in the rendering, the meditative feel of the work and the tone and timbre of the instruments.

Stephen Whittington (PATU Director) and James Cuddeford (Australian String Quartet) gave an absorbing rendition of For John Cage. The music is based on sequences of irregularly repeated short phrases and patterns that change subtly as the piece progresses. Delicacy and nuance sustain the work and one quickly learns to listen for them. Lacking melodic development, the work could be entered almost at any point. Its delightful little twists and turns are teasing rather than dramatic. Instead of entering an emotional or analytical state, the listener relaxes into quiet joyousness, the music sustaining a unique level of awareness and a sense of gentle motion. It suggests the combination of form and time, like watching the creation of the abstract paintings that enchanted Feldman. The music is typically Feldman, rather than Cagean. Despite the lack of linear development, it’s highly complex. The listener may well be oblivious to the discomfort presumably experienced by Feldman in recording his ideas and by the musicians who deliver them.

By contrast, Cage’s homage to Feldman, Music for Piano No 3 for Morton Feldman (1953) consists of a few brief piano notes, the pianist’s right hand on the keyboard, the left on the strings, a kind of musical haiku that in one moment contains many subtle moods and tones. Cuddeford’s performance of Cage’s Chorales for Solo Violin (1978), a series of 9 short movements for solo violin based around carefully devised microtones, is engrossing, as is Whittington’s powerful rendering of The Seasons(1947), written during Cage’s exploration of chance and numbering schemes.

Whittington’s August 9 program included more works by Cage and some rarely heard composers influenced by Satie including William Duckworth, Peter Garland, Terry Jennings and Philip Corner. (Satie was also featured). Duckworth’s energetic Imaginary Dances (2000) inserts country blues idioms into postminimalist structures. In contrast with the late modernist, idealistic compositional sensibility of Cage and Feldman, Duckworth’s post-modernism combines contrasting musical styles and traditions. Whittington also performed his own Custom Made Valses, a tribute to painter, customs officer and composer Henri Rousseau, in which he alternately read texts on the artist’s enigmatic life and played works evoking his eccentricities.

Cuddeford is a prolific champion of contemporary music. At ACME’s November 5 concert, he gave us Pierre Boulez’s Anthemes for solo violin (1992), a comparatively approachable work (for Boulez) in which pizzicati and slurred notes engage conversationally. Cuddeford’s own sublime and engaging composition, Kodoku, for solo violin (2002), performed by ASQ leader Natsuko Yoshimoto and based on 32 overtones of A and E, perhaps owes something to Cage and Feldman.

In the cavernous St Peter’s Cathedral, after warming up with Shostakovich’s 1934 Cello Sonata, Gabriella Smart’s Soundstream Ensemble launched into Henryk Gorecki’s immensely challenging Lerchenmusik, recitatives and ariosos for clarinet, cello and piano (1984). Stark and austere, Lerchenmusik is more typical of Gorecki than his legendary gentler and more accessible 3rd Symphony. This well-played 40-minute work is based on repeated patterns of a few notes during which slow, quietly sonorous, prayerful passages alternate with intensely loud, dramatic moments. The wide-ranging dynamics and metre emphasise the spare melodic lines. Fragments quoted from Beethoven’s corresponding trio briefly punctuate the final movement, as if Gorecki is looking back with post-cathartic relief on European (musical) history.

For some reason, Adelaide’s contemporary music season is largely squashed into the second half of the year. It also included The Firm’s 7-concert season showcase of excellent, though sometimes conservative, new work. Craig Foltz, Sarah Pirrie and Erik Griswold brought Permanent Transit to PATU. And ACME’s sole concert also included Director David Harris’ new works. This year’s Adelaide’s contemporary music scene has grown in diversity and quality of performance.

Stephen Whittington, Performing Arts Technology Unit, University of Adelaide, Aug 9; with James Cuddeford, Nov 8; ACME New Music Company; ABC Studio 520, Nov 5. Soundstream; St Peter’s Cathedral; Oct 25.

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. 39

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The NOW now festival was first held in January 2002, growing out of the fortnightly concerts of improvisation at Space 3 Gallery in Redfern, Sydney. The festival and Melbourne’s Make It Up Club have recently received a grant from the Music Board of the Australia Council for MAKE IT NOW, a mobile festival including both Sydney and Melbourne improvised music festivals and 6 interstate tours of national artists over the course of 2003. In this edited interview RT talked with Clayton Thomas (festival co-director with Clare Cooper) about the ethos behind the of the NOW now festival and the growing interest in improvised music.

A scene is born

We couldn’t find a venue so we did a concert in a basement garage and the people who ran Space 3 said why don’t you come and do a concert next month at our gallery. And we [Matt Ottignon, Felix Bloxom and Clayton Thomas] did our little trio and 150 people came, which is pretty unheard of for a free jazz gig in Sydney. Then I went away for 3 months to New York and became involved in the free jazz community there. That really initiated a whole lot of ideas in terms of how easy it is to form a community just through effort and, hopefully, if what you’re doing is positive and has the right spiritual aims people will gravitate towards it. For a few months there it was a little too focussed on the people Clare and I knew but gradually it’s ballooned. In January this year, everyone knew about The NOW now festival—the jazz scene, the electronic music scene—and suddenly there’s 100 new musicians we didn’t know. An important part of it was to break down cliques. So we have jazz musicians playing with experimental noise artists…that’s happened before but not with the same kind of open energy…the impact is creating new music. There’s not really a doctrine. Well there is, but it’s not like an aesthetic doctrine. We’re pursuing what happens when you improvise. So one night it’ll sound like a free jazz gig, like the Ornette Coleman Trio, and for the next set it might sound like somebody rolling a truck down a hill. Next week these artists will be collaborating. It’s just been the most organic thing.

What’s on

First we have the return of Jim Denley who’s been in Belgium for most of the year. Cor Fuller is coming from Holland. He’s a piano player and electronic musician. Mike Cooper is coming from the UK and he is a dobro slide guitarist, Polynesian music specialist and improviser. We have a contingent from New Zealand—Jeff Henderson the baritone and alto saxophonist is coming with drummer Antony Donaldson, one of the elder statesmen of the free jazz scene in Wellington, and a bunch of younger musicians. From Melbourne we’ve got bassist David Tolley [part of the MAKE IT NOW initiative], saxophonist Tim O’Dwyer, percussionist Will Guthrie and Tasmanian guitarist Greg Kingston. The country’s great improvisers are going to be here and all of them are going to be collaborating with Sydney musicians. One of the highlights of the festival will be Mike Nock the pianist playing with Anthony Donaldson and David Tolley, like no piano trio anyone’s ever heard. They’ve all been wanting to play together for 20 years. Then we’ll go down to Melbourne. It’s a mobile festival with 6 tours throughout the year of musicians from around the country doing the Sydney-Melbourne-Canberra leg and maybe Adelaide if possible. It will involve musicians from everywhere.

Connections – Make It Up Club

I guess Make it Up Club is an identical situation to Space 3. They do a regular series of improvised music concerts and a community has formed around a venue. If there’s a venue that’s specifically oriented towards something then people will find out who’s involved and suddenly you’ve got a community. They’ve been doing it for a couple of years. Tim O’Dwyer was up here doing a tour a couple of years ago and we met and shared some musical visions and through him we’ve met a whole bunch of Melbourne-based musicians. Just basically through our activities a whole bunch of people have become involved, either they relate to the Tasmanian scene or the New Zealand scene. Jeff Henderson runs the Space in Wellington–the exact same model as ours. It basically functions because of his energy. Three years ago he said we’re going to have an improvised music scene and he played there every night for 8 months and slowly people and his band got a little following and more musicians turned up and now it’s a 7 day a week venue. And it’s the creative hub of Wellington. Just through that the Wellington International Jazz festival is probably one of the most progressive jazz festivals in the world–there’s a community that’s looking for great music. I’ve just come back from 3 weeks there and it was mind blowing. The high level of music and creative content in such a small town is like frightening. And it’s all because the space has kind of demanded that everyone play—so they’re all teaching each other.

Why now?

I think we’re living in a really complicated time with the threat of institutionalised decision making, Like America deciding that everything is open to attack. I think improvised music and improvising in general, and the freedom to bring to your ideas and expression and 100% of your energy to something, is really important. People are looking for that challenge: music as a model for life. It’s liberated and difficult and disciplined.

the NOW now festival, Space 3 Redfern Sydney, Jan 13-18, 2003. For full program details go to www.thenownow.net

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. 39

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

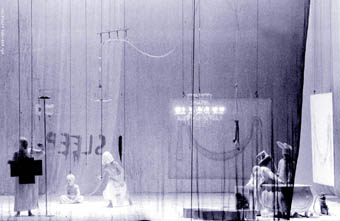

Genesi

This interview with Romeo Castellucci, Artistic Director of the Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio Theatre Company from Italy, and director of the company’s Melbourne Festival production, Genesi: From the Museum of Sleep, was conducted shortly prior to the opening of the show. Castellucci’s original, unedited Italian text has been translated by Paolo Baracchi, with French translation by Baracchi and Marshall. Comments in brackets are by Jonathan Marshall. An excerpt from this interview first appeared in IN Press.

Introduction

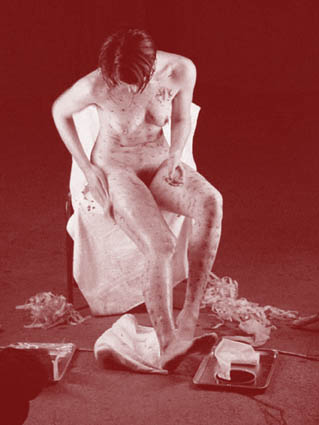

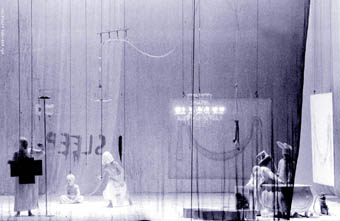

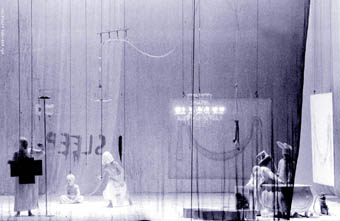

An elderly, naked woman, possibly Eve (who has had a mastectomy), traverses a diagonal line towards the front of the stage and clumsily fondles some white thread. A monstrous spindle-machine starts behind her as her hair drops from her head and we realise that it is this which is being spun.

This is but one image from Romeo Castellucci’s staging of the Genesis myth–complete with elements from the Apocrypha (the non-official Bible) such as the Fall of Lucifer from highest angel to a hideous, deformed mimic of God who facilitates the chaos that underlies all of Creation. Like Antonin Artaud and the Theatre of Cruelty tradition which the former-painter-turned-director is steeped in, the stuff of Castellucci’s theatre is stuff itself: matter, that which you and I swim in, yet which becomes strangely amorphous, slippery, weirdly sexual, deformed and impenetrable in his hands.

The story of God lovingly creating the universe, after which Man committed the first sin and was expelled from the Garden of Eden, is well known. Less familiar however is the mystic, Judaeo-Christian version found in Gnosticism, the Kabbala and Rosicrucianism. It is this version which Castellucci portrays through the use of sound, physical performance and massive, spectacular effects. Castellucci is tapping into the same traditions which served as the inspiration for artists such as Baudelaire, Antonin Artaud, Peter Brook (The Mahabarrata, Marat/Sade, etc), Carmello Bene, the master of Italian avant-garde cinema Pier Passolini, Jerzy Grotowski, the founder of the Japanese avant-garde dance form butoh Tatsumi Hijikata, and others.

In this darker version of Genesis, the act of Creation is not one of love, but a horrible mistake. The Kabbala for example talks of the universe being created when the sacred pots carrying the Word of God were dropped, exploding into millions of imperfect shards. The act of Creation is therefore a violent transgression against the laws of the universe–and hence all of Creation contains within it the seething chaos of a proto-universe just prior to the act of Creation itself. It is not Love which rules this universe, but Cruelty. It is not Man who sinned, but God. All of art, theatre and history therefore constitute a retelling of this initial act of primal violence, in which events like the Holocaust, September 11 and the destruction of Afghanistan are the norm, rather than the exception.

Castellucci’s essential thesis in Genesi: From the Museum of Sleep is that in the shift between an idea, a thought or our conception of any given thing, to its actual manifestation, something monstrous has taken place. We have violated cosmic law, become like God (or Lucifer) and tried to create something. Castellucci’s theatre is therefore one of cosmic dreams and nightmares, of temporal shifts and suspensions, such as the incredible second act set in Auschwitz, bathed in an unsettling yet warm, white glow, where literally nothing happens–as though the Holocaust has somehow killed time. Genesi strives to be very nearly, if not actually impossible to consciously understand, a work which one must apprehend, experience or perhaps merely endure. It exists in a radical, Dionysian realm beyond tragedy, beyond description and possibly beyond language itself. It is a work as complex as it is compelling, as bizarre as it is raucous. Operatically boosted by an incredible electroacoustic score by Lilith [Scott Gibbons], it shifts from dense screams to low, crunchy disturbance. It is a work as full of piety as it is full of sacrilege, as dense with allusive meanings as it is a deliberate staging of the absence or failure of meaning.

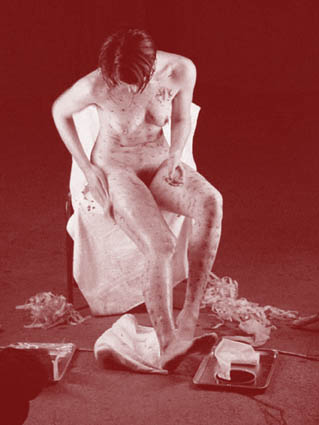

Why do you use the performers that you do? What is it that these performers offer that formally trained actors do not? Could you also tell me about the use of the body in your performances, and the choices that you have made in casting performers with various physical attributes? I am particularly interested in your casting of Cain.

In truth, every body is worthy of being on stage. For me there are no deformed bodies, but only bodies with different forms and different beauties, often with a type of beauty that we have forgotten. I believe that each body expresses something–any form of body. The age of an actor is important, as is how much actors weigh, how they twist their neck one way or the other, what their hands are like: these are all fundamental elements, much more interesting than the actor’s profession or professionality. Actors, in the moment when they let themselves be truly seen, are always the worthiest beings, and in this respect they represent the only possible form of performance. So, it is no longer a question of graceful or unpleasant, of professional or not, of fat or thin, of being a child or an old person. It is about sharing problems of art with these people. It is about interpretation, and not the presentation of reality. When one attempts to represent ‘reality’ on the stage, this always transforms the spectator into a voyeur. But here, in my theatre, performance is not about making a ‘theatre of truth’ or ‘social-theatre’, in the older sense.

Often, moreover, non-professionals attain an amazing ‘truth’ in their acting because they retain a capacity of surprise and a naturalness which many professionals have lost. The choice of actors is therefore based primarily upon the discovery of the beauty that is present within each of them and upon the necessities of the theatrical production. My theatre is open to all experiences and I always learn a lot in my work with the actors. I assign the characters and then I give the actors the freedom to act how they feel. I do not have a ‘method’ as such, but rather proceed according to the show, relying on the qualities and the gifts of each performer. For example, the actor who plays Adam in Genesi is a contortionist, and that makes him a perfect presence for this production. The actor who plays the role of Lucifer is a singer. We have worked on rhythm, on voice and with the sonorities of the Hebrew language. [Act I opens with Lucifer in Marie Curie’s laboratory, reciting from the Torah, accentuating various cutting, consonant sounds, as he traces characters from the text in the air. Adam later appears in Act I as part of a museuml tableau, in a glass case, a mounted crocodile suspended above him, violent electroacoustic cracking sounds accompanying his contortions.]

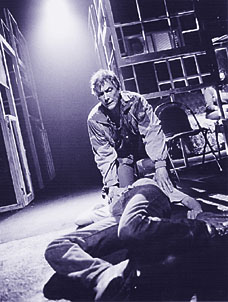

For the choice of the actor that plays Cain I have taken into consideration the fundamental fact that the fratricidal act had to be, in some way, innocent, infantile. For this reason I searched for an actor with one arm shorter than the other. The un-grown limb immediately suggests childhood, and the homicide becomes more complicated by adding to the violence of the act itself the ambiguity of a game that has, unfortunately for Cain himself, become definitive or irrevocable. The shorter arm bears witness to the fact that this is a game which, unlike all other games, cannot be started again, because its result has been fixed once and for all with this act that causes death, in the same way in which the arm has remained fixed in its childlike size. [In Act III, Cain embraces Abel about the neck with his withered arm and Abel collapses, dead, after which Cain gently attempts to coax the body back into life before he lies on top of his brother.]

Could you tell me a bit about the use of sound in the production? Why have you and Gibbons used the granular synthesis of images to generate sound, in which the digital mapping of various images from the history of visual art and iconography (the classical statue of “The Thorn-Puller”, Massaccio’s painting of “The Expulsion From Paradise”, etc), as well as turn of the century photography and science (Henry Fox Talbot’s early photography, Curie’s laboratory, Étienne-Jules Marey’s cinematic studies of motion, Francis Galton’s studies of atavistic racial physiognomy, X-ray diffraction patterns of DNA, etc) are transformed into sonic patterns? Can you really translate images into sound, or does this process in fact create something else, something perhaps more comparable to an unimagined sound or what French composer Pierre Schaeffer described as music for the “astonished ear”?

The sound is an integrative element within my shows. It has a body that is born out of its own dynamic, under the impulse of the alternation between din and silence. In general, the sound is not derived from any particular visual, sculptural or linguistic figure because it constitutes, in itself, a figure. The quality of a work may often be conveyed in a clearer fashion through the use of sound than by means of images. Sound opens perspectives and prepares the [scenographic or dramaturgical] field for creation. It is like a stream that carries forms. Scott Gibbons’ “granular” music transforms the sounds in such a way that they seem as they would, if they were perceived by the ear of an embryo.

Gibbons has developed sounds using a numerical technique called “granular synthesis” which he applied to various photographs I sent him every week from my home. Scott has been able to transform them into sound impulses. [In the program, Gibbons notes that this involved such transformations as “height mapped to pitch, color to stereo position, brightness to amplitude, etc”.] Some were anonymous photographs dating from the end of the 19th century, as well as some other things which I found in old manuals. Gibbons has thus been able to give voice to certain images which I felt were intimately connected with the show. From this, some scenes were born with sounds, and other sounds were born from certain scenes. Here too, it is one single emotional wave. There is no distinction made between these elements.

What is the role of text in your work? Do you think that your work is more eloquent than traditional, scripted, text-based theatre? It is has been suggested that most of the spoken words in Genesi are predominantly there to create musical effects, rather than to impart specific information, specific meanings, or to relate details of character and plot.

All of the scenic elements have the same importance. The process is comparable to the one employed in developing photographs. There is a dark room and a bath of acid. All the components of the image (colours, forms) emerge at the same time. The different elements are not placed in an hierarchy–simply because the human organism perceives emotional waves in a global fashion. For me, an initial text cannot prevail over the other elements, because then everything that comes afterwards would be an illustration, and illustrations only release a compensatory force which does not interest me.

Nevertheless my theatre is based upon the strongest of all possible relationships with the text and its words. This is a relation of struggle and antagonism. If the text remains an essentially literary product, then this means that the theatre has become nothing more than an illustration of this text or, at best, a recontextualisation of it. Within theatre itself however, the text must be definitely brought out of the literary container and allowed to transform itself into a literal, carnal power. Words are not essentially spiritual things. No, the word is first of all a muscular contraction, something physical. The word must be a body which it is possible to weigh, to illuminate. It is necessary for the word to have a body [even if only to be spoken]. In this way, the word is treated technically. It is treated exactly as every other element of the scene, each of which also has a body, just as the word does. And each time words are framed, this is only really possible within the dramaturgical frame. [Castellucci is implying that the embodied actions of theatre constitute a superior and more profound realisation of textual material than any other form.]

Would it be fair to describe Genesi as a Medieval Mystery play (the Medieval works depicting stories from the Bible and the Apocrypha) for the post-20th century world?

It is an evocative question, because the Middle Ages offer important suggestions–not, however, in the theoretical field of dramaturgy, but in the sense that this representation is neither born nor develops within the context of the ecclesiastical pedagogy which was typical of the Medieval theatre. Nor does this version of Genesis communicate the revealed truths of [religious] transcendence. Rather, this production remains totally within the immanence of the human condition, not transcending it, which situates this production particularly within the condition of the artist. The dramatic morphology on the other hand, although it remains distant from the action-followed-by-consequences structure of previous sacred representations, may nevertheless be said to have a certain connection to the Catholic model of spiritual ‘stations.’ Genesi too is effectively structured according to such thematic pictures. [The 14 Stations of the Cross are a series of devotional paintings or sculptures representing the Passion of Christ. The Stations mark His progression towards martyrdom and Transfiguration.]

You have stated that “Genesis scares me more than the Apocalypse” because it represents “the terror of endless possibility.” This would seem to draw heavily upon the writings of Antonin Artaud and Herbert Blau, as well as the Gnostic and Kabbalistic doctrines which Artaud himself was influenced by. Would you agree with the ideas usually associated with this cosmology? For example, Artaud contended that a terrifying chaos existed prior to Creation, and that this remained forever present, latent, or immanent within everyday existence. He argued that this “chaos” is the logical “double” of theatre. Is theatre’s highest aim and greatest virtue therefore that it can represent–or at least come close to representing–this chaos through live performance?

There is a tradition of Western theatre that is totally forgotten, cancelled, repressed: the tradition of pre-tragic theatre. And it is repressed precisely because it is a theatre that is closely linked to [the transformation of ideas, thoughts or ideal forms into] matter and hence with the anguish of matter itself. This form of theatre is linked moreover to a primal presence or power that is doubtless female. It is necessary to understand how the female aspect (in the mystery of the gestation of life and in the wardenship of the dead) is an aspect that is also involved in artistic expression, which has in turn found in this female component a relation with real life. This ‘female force’ runs from birth to burial.

If the great domain of open possibilities belongs to God, the fact that certain possibilities are joined together and made to happen must therefore belong–according to some Kabbalistic traditions–to the weight of the body itself. God must transform Himself into something “of the flesh” so as to be able to manifest possibilities that would otherwise remain unrealised within an inconsistent world. It is possible [according to these traditions] to experience possibilities through the invocation of material, carnal elements, and, through a conjunctions of these, to experiment with them.

Theatre is not something that must be ‘recognised’: “I-go-to-the-theatre-to-recognise-the-Shakespeare-studies-that-I-have-completed”. It is not [or should not] be like that. Theatre is rather a journey through the unknown, towards the unknown. What myself and those of a similar mind have tried to do over the years has been to hold high the scandal of the stage and to keep it constantly vibrating. Even the word “theatre” itself has to be continually re-invented, because it is a word that has completely lost its radical meaning. The stage is in fact a place of alienation, and nothing must be done to anaesthetise this alienation. The ‘problem’ of the author, of the text, of the tradition of narrative theatre has always been, in actuality, an attempt to solve this ‘problem’ by filling in the scandal which theatrical creation represents with various discourses, by forcing the actor–and therefore the actor’s body–to become nothing more than a repeater of these elements, diminishing the energy of the stage itself.

In this regard, I believe that the thought of Antonin Artaud is of fundamental importance for the whole consciousness of Western form. It plunges the problem of form [as in what form should an idea, thought, or aesthetic act take once made manifest within the material universe] into a bath of violence that re-awakens that which supports a true theatre. It is then that form becomes spirit. One is, in fact, here talking about the alchemy of transformation, of the transmigration of one form into another. There is of course an aspect of Catholicism which influences, and inheres within this type of theatre, which is connected to the moment during the Eucharist when the Host is transformed into the Body of Christ. This Eucharistic fact also is an idea that we find within Artaud: this idea of transforming a body, of donating a body, of cutting a body to pieces, of liberating a body from its organs: these are all elements that derive from such a Christian conception.

The terror that you were alluding to from the Beginning derives from the fact that one no longer recognises language [at this moment when one encounters the chaos], and this causes terror. One no longer recognises that which connects us to each other within the human community [that which allows us to communicate, to think and to express ourselves]… Words become disconnected from the things we know and precipitate within this undifferentiated state. But only from there can “your” true language be born again.

Do you think that these type of ideas have taken on a particular relevance in the light of 20th century events like the Holocaust, and indeed more recent events such as the Yugoslav Wars, September 11 and the decimation of Afghanistan?

The events that you have recalled, the massacres, the genocides, the disasters that humankind has experienced in its recent history, constitute an abyss which is necessarily connected with the experience of Creation. During Creation, it is the Word of God that creates; in these events however, there is His silence. The theatre is called upon to comprehend the heights and the abysses of human experience–but not through illustration, nor by means of the production of information. The experience of abomination is too deep to be consumed on the surface [or through such superficial means as by the representation of mere appearances]. It is necessary now that we should all begin to consider the term “tragedy” so as to collectively rethink the destiny of humanity. The theatre is called upon to address this task through the radicality of its form, which is that of a living art.

Following on from this, would you agree that all creative acts constitute an act of violence, or at least a violation of the taboo against creation? I have in mind here your suggestion that the fallen angel Lucifer is the first artist with whom humanity can identify.

Naturally, the theme of Genesis highlights the problem of the Beginning. At the Beginning each artist knows that the empty stage is an open sea of possibilities. This is also what constitutes the ‘terror of the scene.’ This is not–as far as I am concerned, in any case–a terror or fear of emptiness per se, but rather a terror of fullness: there is too much world. Quantity submerges us. Matter is obscure. Therefore, every time the artist elaborates upon this chaos so as to make something come out of it, one reconnects these possibilities. Lines and constellations are then created… by parthenogenesis, almost independently of one’s personality. With respect to the Beginning and the End, it is evident that theatre has in itself, ontologically, within its deep textures, this problem of the Beginning and the End–because they are co-penetrated. Theatre is a corporeal art par excellence which, by definition, when it “is really here”, in front of the spectator, it is also ending at the same time. Theatre is born at the same time as it dies, and vice versa.

What meaning does it now have to repeat those words which are the first words of Genesis itself and so are, indeed, the things themselves, the world itself? Are these words from Genesis the words which made the world happen, and so also those which have given rise to the stage? The only person who could bear the weight of these originating words is he who first spoke in a ‘double form’, he who first assumed the costume of another–namely Lucifer. Throughout the history of humanity, Lucifer has always made himself felt through disguises and costumes, assuming the words of someone else. He did this also at the Beginning, assuming the skin of the Serpent and the language of the Serpent. He duplicated for the first time the words of someone else, saying: “Is it really true, what God said?”, hence creating a form of mimesis, a form of duplication of language. He is indeed the first to work in the superabundance of language, to exploit the theatre as an energy, and hence also giving rise to art. Art finds in this originating nucleus its privileged relation to evil. Evil is moreover the extreme aspect of the freedom that God has conceded to all beings. Lucifer lives in the condition of his condemnation which is, quite precisely, to live in the region of non-being. In order to return to the state of being, Lucifer is forced to assume someone else’s disguise, someone else’s voice. Art becomes necessary when one is no longer in Paradise. In this sense, the only person who could endure the act of speaking again God’s words, let alone in their original language of Hebrew, was Lucifer.

In Genesi, Lucifer’s conference is held on a little table, in the study of Mme Curie, in a drawer of which is contained a little stone of radium. Radium is, among other things, a stone that emits a light of its own [Ital. luce]. Radium is therefore mysteriously close in etymology to the word “Lucifer.” The true radioactive nature of radium’s glow was not known at that time. It was nevertheless a light which penetrated bones; it had something evil about it. It was also however the light of knowledge, which one could relate to the games which art plays as well–this exposing of oneself continually for one’s own ends.

Could you tell me about the evocation of time within Genesi? You have suggested for example that both historic acts of violence–and indeed their representation in the theatre–are only possible because of a “foetal amnesia” in which we forget the history of violence which this production is itself designed to depict. The Holocaust therefore repeats the murder of Able by Cain, just as the sacrifice of Christ repeats Abraham’s sacrifice of the lamb, or Marie Curie’s discovery of radium repeats the discovery of the Tree of Knowledge, and the actions of humanity repeat the sins of Lucifer (pride, creation, the desire to become like God, etc).

This would seem to suggest that both the content and the style of Genesi are designed to create a very strange sense of time and temporality–or possibly a state in which time does not seem to pass at all. You have yourself described this as a “state of suspension” which “annuls time.”

How is this achieved and is what I have described above what you are in fact trying to convey?

This question of time in the theatre refers to the experience of another time which theatre founds. I mean the flowing of time. I am not referring to a chronology, but to the quality of time itself. The final lapis of this alchemy which defines theatre is time itself. All of the transformations which I was suggesting before are not designed to do anything other than to modify time, to inaugurate another time. [Lapis is Latin for a smooth stone, as in lapis-lazuli, an ingredient for many alchemical preparations.]

Theatre is, by its nature, an operation performed upon time. Dramaturgy can be defined as the art of modifying the flow of time. Time constitutes a material for the theatre worker, just as colour is for the painter or marble is for the sculptor. Time is a primary raw material to be worked, to be developed according to its dynamics, to be dilated or–on the contrary–to be condensed. This show embraces different qualities of time, which are proper to each of the 3 acts, yet without placing them into any kind of dialectic per se.

The first is derived from Bere_it [first Hebrew word of the section of the Torah dealing with Genesis, meaning: “In the Beginning”]. It corresponds to a reality outside of time. The Creation occurs before the invention of time. The initial relationship of God with the Elements occurs in the obscurity of the darkness and in the absence of time. The second act, which has the name of a town, Auschwitz, precipitates the action into a historical time. The last act, Abel and Cain, evokes a mythical time. These 3 approaches revolve around the fundamentally intertwined themes of creation and destruction. The dramaturgical work therefore consists in making visible [through the action of the stage] the differences which these temporal structures effect upon one’s perception of the flow of time.

The first part ideally unfolds outside of time, and this is rendered symbolically by the obscurity that reigns upon the stage. But Genesis is also a frenzied act which is accomplished amongst the chaos. The stage starts to quake: one sees apparitions of lightning, lateral entrances, entrances from high and from below [several objects are flow in and off stage, including a clear tank of bubbling water, which may represent the unleashed power of radium and Creation], rotations, cacophonic machines that suddenly begin to shake [there are at least 2 of these: the first a flattened, bucking, metallic insect, which the program describes as “Something bronze that is writing”; the second an unadorned mechanical armature at the side of the stage which intermittently applauds the action], bodies that burn, cords which stretch across stage [literally in the case of Eve’s hair], objects that fall from the air, and ground that [literally] swells, which breathes… As if God was surprised by what he was doing in the process of creating.

The flow of time then becomes mechanical, fragmented. [At this point a naked black man appears and plants two carrots into a mound of soil; the Avenging Angel Gabriel appears and grasps the handle of sword suspended in the air, whose blade is aflame; etc.]

Auschwitz, on the contrary, evokes a sense of extermination–even of time. A time which relates to a historical moment seems suspended, swathed in the wadding of a nursery and the unctuous melodies of Luis Mariano. [Act II is set in an open white space where children play at serious, often symbolic games. One enters on a toy train, for example, a yellow star on the back of his jacket, and takes down a series of rubber, human organs suspended above the stage, placing them into the carriages, before departing.]

Abel and Cain however returns to the original homicide. Here, time becomes music. Cain is the first man to face the dramatic duel between the 2 fundamental polarities of human action: the Beginning and the End [ie this first act of human violence nevertheless contains within it the End of all things and hence serves as the final tableau in Castellucci’s exposition of Genesis]. The essential problem of the Creator, of artists, is their permanent confrontation with the void, with chaos. Each act of Creation presupposes a prior act of destruction. Creation becomes then a re-creation, and each phase which precedes this re-creation must be a systematic destruction of all acquired habits [if it is to be true act of novel creation]. It is therefore necessary to destroy the habits associated with words. The same holds true for the word “Creation” itself. It is a word which no longer means anything, as is also the case with the words “stage” or “scene.” These are words whose meaning has been forgotten, falling into oblivion, into inertia. The first task of the artist is to destroy this “tiredness” of words, to re-awaken their sense.

It is also necessary to destroy the habit of acts. It should never be a matter of habit to perform a show. Each time one performs a show, presenting it to view, it must be a scandal of reality. Each performance is a threat or provocation, a suspension of reality, a fissure in the real. The word “creation” is too strong a term if one reads it in the light of reality. One must rather read it as evoking this sense of re-creation.

It is this way that the act of creation and Genesis may be brought together. The only Genesis that I can conceive starts from the idea of this crisis of creation. I can only capture and hold onto such images as might, at least in my opinion, interest someone like God–a marvellous and unique God. The figure of the artist moreover is only extreme within the context of the monotheistic religions–and this is because it is within these religions that the price of shame is greatest. The artist, as creator, has a special relationship with God and the Book of Genesis because it is this Book that puts onto the stage the essence of artistic work or creation. The artist himself can only therefore be a Re-creator. The most violent aspect of this relationship which the artist entertains with this God (who is, above all, the only true Creator) is his capacity to be exposed to ridicule. Each artist is in effect a little Creator or God, but the artist’s creation is ridiculous when placed alongside the work of God. It is a false artefact.

I am not saying however that artists must measure themselves against God. To compare oneself to God is not only impossible, but, in the strict sense of the term, it is unthinkable. God is born incessantly–I tell you this above all as an artist, and there is nothing mystical about this. My show, Genesi, is not only a representation of the biblical Genesis, but it is a Genesis which brings to the world (using the stage) my rhetorical pretensions to remake the world. It puts onto the stage the most vulgar aspect of my being–namely that of the artist who wants to steal from God the last and most important of the Sephiroth. This is the secret of Polchinello too: to steal from God. [The Sephiroth are the 10 mystic attributes identified in the Kabbala as they key to the communion between the Finite with the Infinite. Polchinello was mischievous peasant character, highly disrespectful of his social betters, from 17th century French marionette theatre. Punch is a later, English derivation.]

In short, Genesis frightens me much more than the Apocalypse. The terror of pure possibility is there in this sea open to all possibilities. And there I lose myself in form. The Angel of Art is Lucifer. He is the first Being who puts on and assumes the costume and the clothes of another in order to Be. He has duplicated language and has translated it. The art of transformation is for him alone. He comes from the region of Non-being. The only way for him to return to the zone of Being is to write the name of another with his voice, with his body–and this is what the theatre is. This zone of Non-being is the genital condition of each act of creation. It allows the destruction which is necessary to ward off and avert all superstitions. [Castellucci is highlighting the paradoxical nature of the Judaeo-Christian mystical tradition he is heir to. If one communes with the divine by becoming like God, one also comes to doubt in the unique power of the divine. This is the condition of the director too.]

–

The author would like to thank the staff of the 2002 Melbourne Festival–especially Andi Moore and Ally Catterick–for making this interview possible and for providing translation services.

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. web

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Crickets clack and distant babies cry, the room is quietly dense with tropical night sounds. Five huge 19th century cameras almost fill the small gallery space for the performance installation, Troppo Obscura: they look the real thing, bulky, long-legged, wide-eyed. They are fantastic reconstructions, one is even winged, and they incorporate authentic components, but also come with earphones attached. Beneath one, oddly, a pair of legs in tights is visible. When I look into the view-finder I don’t see the room; instead I’m seduced by the articulate gesturing of dancing fingers, the gently elegant moves of a crowned head and the beckoning of brilliantly bright eyes that pierce with such face to face proximity. It’s as if I have my own camera and am shooting in extreme closeup a court dancer from Java or Bali. Forced to move on by keen queuers, I squint into another camera to see old black and white footage, perhaps from the 20s, of village life and court dancing, children at play in water, the eruption of a volcano and the disturbing recurrence of the image of a westerner gazing sternly at me as he stands by his own camera.

Looking into the winged camera I see more film of engrossing traditional dance. I hear, however, contemporary Australian female voices intimately recorded, chatting, sometimes raucously and wickedly, about relationships they’ve had with Indonesian men, the pleasures and compromises. In another camera, I witness recent footage of an old woman sitting cross-legged, gesturing with a dancerly expressiveness as she tells the story of her first husband, a policeman who wouldn’t let her dance, and the second who was “stupid but obliging.” Her characterful eagerness and dancing hands counterpoint the horrors that spring from her lips of grim privations and dying children.

From above another camera rises the upper torso of a young man (Teik-Kim Pok), a red flower tucked behind his ear. He peers obsessively into a hand mirror. A peep into the machine reveals a different kind of dancing: a kitschy, naked, western blonde ‘tattooed’ on the boy’s belly gyrates to Bob Marley’s “No woman, no cry” and Garuda Airline airport announcements, making for a nicely droll postcolonial mix.

The piece de resistance of this already absorbing Troppo Obscura is a large projection onto one wall of the gallery, It’s a film in silent movie mode of the work’s creator, Monica Wulff (encountered also as the dancer in the camera), appearing as an Edwardian woman in white hat and long dress who plays with Indonesian masks and dance gestures and whose clothes disappear layer by layer and piece by piece. For all her adoption of an exotic otherness, a piece of old peep show trickery reveals her to be very real, naked and white, until the film reverses and dresses her again. Sam James’ filming is another example of the artist's virtuosity (as witnessed in Julie Ann Long’s Miss XL) and his ability to perfectly complement and expand his collaborators’ visions.

Troppo Obscura is a marvellous visual, aural and dance creation, a performance installation that not only seduces with its immediate magic but leaves you wanting to see more of the remarkable archival film that Wulff found in the Netherlands and to know more of the lives overheard. The installation’s wit and inventiveness evokes and subverts a world of photographic colonialism with more than enough contemporary hints that post does not mean past or finished, and that the orientalisms of dance and music that sprang primarily from the 19th and early 20th centuries are still with us as we struggle to nurture meaningful cross-cultural hybrids.

Monica Wulff devised the installation and performed (dedicatedly, her head in a box for hours at a time), Hedi Hariyanto from Indonesia created the wonderful objects, Sam James the video, RealTime’s Gail Priest the embracing ambient and other recordings, and Deborah Pollard was a very active artistic consultant. Troppo Obscura deserves to be seen more widely.

Carnivale & The Institute for International Studies, UTS, Troppo Obscura, Performance Space, Sydney, Oct 10-19

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

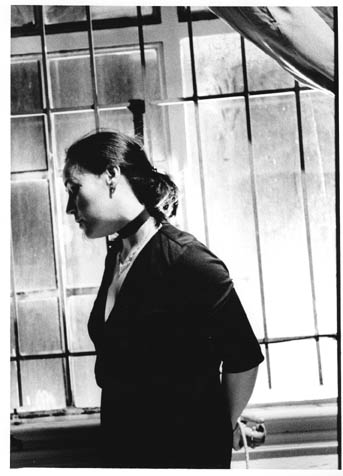

What kind of work does an artist produce when she spends a great deal of her time immersed in a landscape and culture imbued by the world’s oldest stone structures–megalithic buildings from Malta’s Temple Period, 3600—2500 BC? Maree Azzopardi, like other Maltese descendents living in Sydney brings with her a rich heritage. As well, she draws on the influences of Vermeer, Catholic iconography, Islamic mosaics and the advantages of new media technology. Her latest show exhibits a range of both colour and black and white photographs and digitized paintings on stretched canvases.

Azzopardi's images focus on domestic interiors, but she creates a sense of space suggesting intimate temples. She places the female nude in settings with props symbolic of rituals that order life: baptism, the partaking of wine and bread in communion, and the cleansing and shrouding of the dead body. What is eerily subversive is that while the images appear at first romantic, and even nostalgic, there is a distinct absence of signs of life. The beautiful basin and the turquoise water jug do not appear to actually hold any water. Is the reclining female dead? The limp feet on the cold floor by the fallen jug suggest that there may have been a hanging. The lone figure, standing in a basin, holding onto a shroud suggests a final ritual. What story is Azzopardi telling?

Azzopardi’s previous and most celebrated body of work, her Chrysalis series, comprise a series of photographs of HIV patients, both in the process of dying and post-mortem, when she was artist-in-residence at St Vincent’s Public Hospital, Sydney, 1995. It seems that the artist is preoccupied with this ambiguous space, the delicate balance between life and death. The images in this show are less confronting seeming staged, set in a distant place and the female figure anonymous.

There is as well is an odd juxtaposition between these otherwise warm interiors with photographs of sculpted cherubs with their arms raised in joy. Perhaps Azzopardi wishes to convey a sense of triumph, even ecstasy over the sense of loss implied–as in Catholic portrayals of martyred saints? Meanwhile, the viewer is sated with the rich sensuality of Azzopardi’s materials, palette and preoccupation with pattern, light and touches of the Baroque.

Maree Azzopardi, Celeste, curator Jonathan Turner, Michael Carr Art Dealer, Sydney, Nov 5—24

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. web

© Lycia Danielle Trouton; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A drunk, gesticulating with his beer bottle, repeatedly yells “Fuck the…what the…?” at the big pulsing screen with its speedy mix of pre-recorded and live feeds. Only occasionally he takes rare notice of the dagsters who slo-mo swarm about him on their hour long, voguing weave through a contemplative audience stretched out on the grass beneath stars blurred by bushfire haze. Some are like picknickers with their eskies and kids, some in proud Gay Games team clusters. Others are bypassers, more than momentarily seduced by these odd sirens who look less a danger to the audience than to themselves in their obsessive-compulsive staggerings and bizarre fashion model posturings on wire mesh podia that they drag about with them. The drunk is on the edge of the crowd, barely heard, but a security guard hovers, iterating, “I told you, no swearing”, as four-letter abuse words slide across the screens and leap from the argumentative exchanges that envelope us in Barbara Clare’s engrossing dance club musical score. “What?” the drunk rallies, his sense of justice wounded, “But this…this’s homos!!” The guard looms, the drunk retreats into his bottle.

You can slip in and out of Shiver, as it moves close by and into the distance, the gaggle of performers followed by video cameras, photographers and the manipulators of portable lighting, like a media pageant or a fashion shoot. Or you switch to the screen, or shut your eyes and go with the music. Whatever, it does have a curious grip, sending even the odd shiver up the spine as the performers surround you, whispering with the soundtrack, “I’m alright. Are you alright?”, hanging over you with a curiously langorous urgency like half out-of-it Kings Cross junkies caught between the pleasures of the last hit and the need for the next. They are almost stylish in their ragbag collection of wigs, high-high heels and dense makeup, for all the world drag queens. But the duration of the performance and the proximity to the performers allows you to fix on these faces to do your own bit of obsessing about what’s under the makeup, what’s glimpsed beneath the clothes, what’s behind the voices. Four of them are women, but the longest-legged, a most elegant if uncertain mover, says someone afterwards, “is a boy.” You can still be surprised, even at this late date. Two of the group are counter-tenors in long blonde wigs. They often frame the action, moving slowly through the crowd, the meeting of their long locks providing a curiously ritualistic climax to an inexplicable, often hypnotic event. The pre-recorded video makes much of their tresses. The 4 who dance vary their formula slightly track to track, performing with conviction (sometimes on the edge of parody), regrouping, slowly forming exotic tableaux vivant, and loping to the stage (a walk reminiscent of the latest horsey ambulations of fashion models, the soundtrack complementing it with solo neighing) where they briefly line up to make a stage act.

I can imagine Shiver making a greater impact in a dance club–where it would be another, if subversive, part of the overall ambience–rather than in a city park on a balmy evening where it is entirely responsible for creating the requisite atmosphere and where its audience can only observe and are unlikely to move move. Nor is its duration and minimalist variation right for theatre spaces, unlike the earlier parts of the trilogy. Nonetheless, the furious drive of the live editing of the intersecting double video projections pitted against the slower, possessed movements of the performers, the quality calibre of the sound system and the in-yer-ear realism of the vocal recording, and the conviction of the performers make for a sometimes engrossing and curiously memorable experience. But what exactly was the experience? While the multimedia dimension of the show had a thoroughly contemporary feel (the projection of gnomic texts aside), the rest was like virtual reality display in a museum visit: not to say that its protagonists were stuffed, on the contrary, but they read like the detritus of glam rockery and 80s new romanticism, prisoners of the cliches of cross-dressing, but with fervour still, over and above an air of pathos and faded brilliance.

–

De Quincey Co, Shiver, November 7 & 8, The Hub Hyde Park.

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

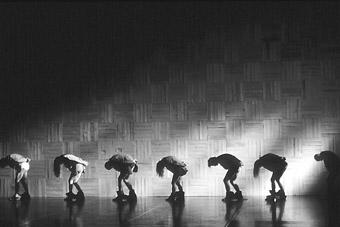

Choreographer Lucy Guerin has established a reputation for herself as a master of minimalistic abstraction with works like Heavy (1998), which dealt with sleep states. Her dance has a kind of devilish funk; of bodies turning into and out of themselves according to a subliminal logic which can nevertheless be very affective. Guerin has also explored explicitly dramatic scenarios through her work–notably with The Ends of Things (2000), which followed a series of endings initiated by an introverted, shy man. Her latest production, Melt, is in some sense a return to her earlier, somewhat more abstract approach, using, as she says: “the relationship between temperature and temperament as a starting point for the movement.”

Guerin explains that she is “rebelling somewhat” against the linear, narrative ambience she adhered to for The Ends of Things. “I felt like that show really made sense. It was closely structured and it didn’t have any lose ends. In terms of what was going on, everything was there for a purpose and a reason.” The sense of some kind of implicit logic unfolding within the choreography has always been a strong element within Guerin’s work, of dancers aligning themselves to each other according to rules scored in the physics of planetary bodies or some other unseen force.

She does however observe that, “often I find that when I’m making a work, I craft a number of sections. Once they are put together though, this other amazing thing might happen. So it’s really not just about those elements being strung together, but that they make up a greater whole–especially in terms of the tone or mood of the piece. And that’s really exciting, to find something that I wasn’t expecting unfolding within the studio. So I’ve left a bit more room for that in this production.” For all of the apparent precision and geometric logic of Guerin’s choreography, it remains rich in evoking the sense that something more has been set into play, shifting from deadpan comedy to weirdly affective distance, gentle rhythms and more. There is always room for audiences to bring their own concerns and feelings to the work and so interpret it in their own fashion.

Guerin observes that this has influenced her in her selection of music (composed for Melt by sparse, atmospheric glitch-funk master Franc Tetaz). “I have tended to choose that kind of music because it allows the emotionality of the dance to influence it,” she explains, “rather than the other way around. If you present an audience with something sparse and simple, then they will bring their own emotions to it. That’s not to say that I don’t want to direct what those emotions might be. Personally though, I find that if I am bombarded with overtly dramatic or hysterical dancing or music, it leaves me as an audience member with nothing to do. I can acknowledge what the dance is about, but that’s all really. Whereas if something is more subtle, I can go looking.” Guerin may therefore use ideas like states of temperature or sleeping as an inspiration for her choreography, but her work cannot be simply reduced to such references. It has the same kind of richness which one can find in some of Kraftwerk’s music, Mondrian’s painting, or the clipped dialogue of film noir.

Guerin’s style lies unambiguously within the realm of contemporary dance, drawing on the post-World War II styles sometimes classified as postmodernist. Her choreography nevertheless has the sharp, minimalistic precision and the attention to clean lines which was the defining characteristic of influential New York City Ballet choreographer: neo-classicist George Balanchine. I suggest to her that there is therefore some kinship between her work and that of Balanchine’s successors, such as NYC Ballet choreographer Christopher Weeldon (whose Mercurial Manoeuvrers featured in the recent Australian Ballet trilogy United). Although Lucy points out that “I haven’t actually seen a lot of Balanchine myself,” she nevertheless concedes that she is also: “very interested in purity of form and in starting from a very clear, structural idea, and Balanchine’s work does have a very clear style or overall aesthetic. Even so, my work doesn’t really look anything like his.”

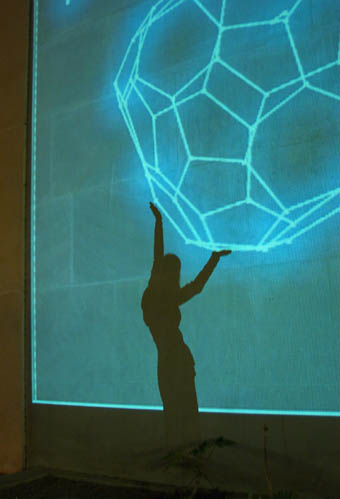

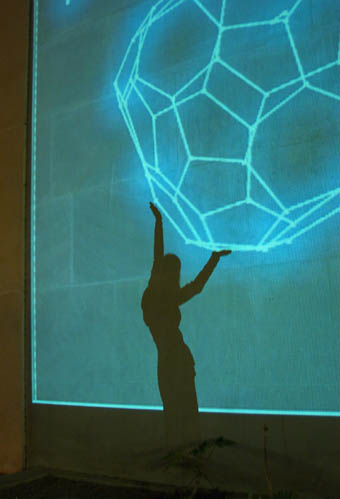

The body shapes which Lucy herself tends to focus upon have much more in common with the pointed articulations and spiky dynamism found in the work of companies like Gideon Obarzanek’s Chunky Move or Philip Adams’ balletlab (with both of whom Guerin and several of her dancers have collaborated). “In Melt, I’m working with a lot of very intricate hand movements and finger details,” she explains. “I always have looked at that in my choreography”–as with her commission for Chunky Move’s Bodyparts (1999). “I’m interested in how joints and bones intersect, and fingers are very good for that kind of exploration. So there is a lot of connecting of fingers to elbows, to knees and to each other to form these lattices.” Although Guerin tends to eschew the break-dance influences found within Obarzanek’s work, her dancers can nevertheless be found on occasion tying themselves into intricate origami on the ground.

Even so, Guerin’s own choreography has a more lingering, almost photographic style of pausing and rhythm than either Obarzanek or Adams–a quality which she explains helps to create “a certain tension” in the movement and the emotional dynamics produced by it. The extremely fast, aggressive shifts which one can observe in the movement crafted by her peers–”that random, crazy sort of chaos,” as she describes it–is not a feature of her own style. “I enjoy watching that kind of material,” she observes, “but generally things in my own choreography are more well-defined. When I work on that kind of stuff myself in the studio … it’s just not me!” Like thawing ice, Guerin’s crystalline choreography proceeds at its own pace.

–

Philipa Rothfield’s response to Melt appears in this online edition of RealTime.

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The middle class, male mid-life crisis is at the dead heart of this new opera from playwright and novelist Joanna Murray-Smith and composer Paul Grabowsky. The friends Edward and Roger no longer love and admire themselves, and their wives’ affections and care for them are no solace. We learn little of these men’s lives, personalities and feelings, and even less about the other characters in Love in the Age of Therapy. The bland wives, Alice and Grace, only become interesting in Act II when new loves take them from their husbands and they are allowed to indulge in romance, lust, hypocrisy and, in the case of Grace the therapist, seriously unethical behaviour. Edward and Alice’s daughter Rebecca, loved by Rory, a radical young poet, and adored by her godfather Roger, is barely realised at all. Rory only adds up to the cliches he mouths, sounding more like someone from the 1970s than the first decade of the 21st century, an indication of how just out of touch this work is.

But all is not lost. Many passable and sometimes good operas have been written to execrable libretti. In this case Grabowksy’s rampant and fluent polystylism (which he calls “avant lounge”) kickstarts the heart of the work and engenders distinctive voices and hints at possibly complex personalities, and the singers rise to the occasion. While the text relies enormously on abstraction and aphorising (nothing Wildean to report, I’m afraid), the music is richly textured, highly animated and framed with a moody, cosmopolitan jazziness. There’s care not to mock characters or to simply parody musical styles. When, a la Puccini, George sings his love to Rebecca, there’s pathos but not bathos, and great commitment in the singing; or when Edward, pressured by Alice, has his first session with Grace, the music is an anxious, restrained, steely shimmer that refuses to dramatise what is already evident. However, the angular, wobbly bebop trumpeting that follows is a bold move that lifts into the open the tension surrounding Edward’s potential release. The music of Love in the Age of Therapy is energising, the sometimes jazz-based phrasing of the libretto undoing the awkwardness and banalities of everyday dialogue (few composers past Britten have managed this) or Murray-Smith’s dogged impulse to aphorise–”Marriage is the art of irony”; “We forfeit the wilderness of passion/For the white picket fence of affection”; Alice: “How do you teach a child what love is?” Edward: “Love them well./Eventually they will recognise the truth/Of its absence”; and so on and on.

There is one other character in this opera, Henry. He lives on the street wearing an old greatcoat and with his possessions in a supermarket trolley. He’s an ironic observer of the lives of the well-to-do middle class: exactly how he sees into their lives is not entered into. He’s a mere device performed with a gruff and engaging physical vigour and musical mock-baroque verve. He’s funny, some of his observations are acerbic, but why is he there at all? The pretensions of the characters are already gently undercut by everything they themselves say. Henry has little to add. There’s also something terribly old-fashioned, cliched, even offensive, about this fantasy of the insightful outsider (homeless or savant or mad).

Halfway into Act II, the work becomes more interesting, even engaging, thanks to the accleration of plot, the intensification of the comedy of sudden reversals (Lyndon Terracini as the irascible Edward showing fine comic mettle), the acuity of Richard Greager’s realisation of Roger and the rapid interplay of sung lines. I felt a lightening of the burden of the ponderous unfolding of Act I. Judiciously edited, Love in the Age of Therapy could make a better, long one act opera.

Also ponderous, Dan Potra’s set represents a monumental middle class bunker (at odds with the several references to the, surely metaphorical, white picket fences in the libretto), appropriately stark and vacuous. Its walls and windows double as screens revealing shots of traffic, skylines and trees. It’s all nicely done but, a few moments suggesting subjective states aside, achieves very little beyond setting mood and background (a predictable mainstream response to the potential of new media).

Love in the Age of Therapy is a cosy bourgeois entertainment, its judgment of its subjects just too kind. There is nothing unfamiliar in their world–they never encounter the likes of Henry. The strangers they meet are themselves until they renew their lives by shuffling relationships: Edward pairs with therapist, Grace (wife of Roger), Alice (wife of Edward) with her daughter’s Rory, daughter Rebecca with her godfather, Roger. One of Henry’s few worthwhile barbs is a comment on the middle class confidence with which they’ve done all this, “This bunch could reorder the seasons/Given half a chance!” Other lines, like “Whoever thought swinging went out in the 70s/Had better think again” are less bracing.

In her introductory note in the program, Joanna Murray-Smith writes that “contemporary culture has diminished the glory and elegance of love, of true love”, but Love in the Age of Therapy itself does little for love other than to intone the word at every turn. The opera facilely abandons all old loves en masse for new. Yes, the characters get another chance at life, but is this enough, especially for a comedy that self-consciously wears Shakespeare and Mozart on its sleeve? There is nothing here to suggest the disturbing complexities of the same playwright’s Nightfall. Musically, Love in the Age of Therapy is a treat, assured, beautifully and distinctively orchestrated even if its many referencings occasionally threaten to overwhelm the sense of a singular and memorable voice that wittily and dramatically fuses and juxtaposes disparate musical languages. If nothing else, Love in the Age of Therapy has given Paul Grabowsky the opportunity to ably compose for dialogue after working on the one man opera, The Mercenary.

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. web

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

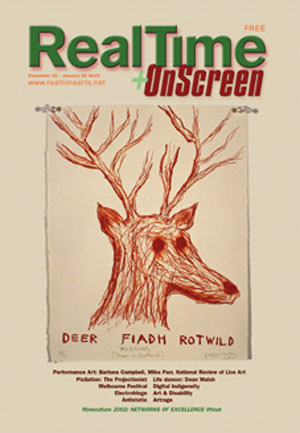

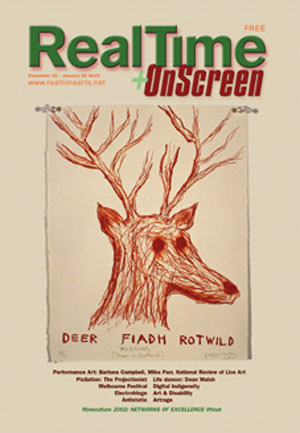

Missing (Deer in Scotland), 2002, Lithograph on paper, 38cm x 28cm.

Reproduced with the kind permission of the artist

Missing (Deer in Scotland), 2002, Lithograph on paper, 38cm x 28cm.

While the deer on our cover may signal Xmas, he’s actually with us because Greg Fullerton’s drawing has been staring at us in the RealTime office with those deep, dark eyes for most of the year on the card announcing the winners of the 2002 City of Hobart Art Prize where Missing (Deer in Scotland) was Highly Commended (judges Peter Timms, Benjamin Gennochio, Grace Cochrane). We’ve grown very attached to this deer and thought we’d share him with you. The artist aptly describes the lines in his drawing as frenetic and the antlers as almost like trees: it’s this organic quality which appeals to us, as well as admirable fusion of cartoony vigour and something more serious.

Greg Fullerton is currently based in Melbourne, though he’s lived in many places and was Visiting Artist at the Edinburgh Print Workshop in 2000 when he created Missing (Deer in Scotland) as an anonymous intervention, protesting the diminution of the deer population, printing it in poster format and sticking it on trees and buildings in Scotland, Ireland and Germany. He describes Missing (Deer in Scotland) as “a protest, satirical, and a bit personal.” Part of the personal is Fullerton’s great admiration for Joseph Beuys, artist and interventionist, in whose adventurous life and work the stag magically figures.

To our readers, subscribers, advertisers, editorial team members, our many writers, funding bodies and the innovative artists whose works thrill and propel us, have a Merry Xmas and a Happy New Year. See you in 2003!

Virginia Baxter, Keith Gallasch, Gail Priest

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. 3

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Must be the season of the witch. October in Melbourne. Just before the magical or lacklustre work of the ‘leading creative artists’ installs itself into the major performance venues around town for the Melbourne International Festival, the Fringe and the fringe of the Fringe occupies the nether regions. It is as if the very spirit of theatre (I speak here only of theatre–though the Fringe gives expression to all art forms) spreads itself out into the warehouses and barns of the city and suburbs and energises them. The Fringe is a field of energy across the metropolis. The works and artists involved both feed and partake of the energy. Any one of them is somehow integral to, but less than the whole. What is truly amazing is the variety of works, performance spaces and audiences that weave the witch’s spell.

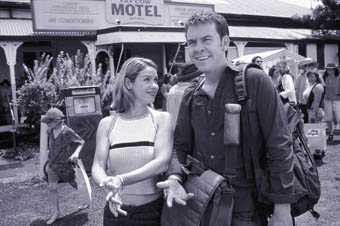

Red Stitch Actors’ Theatre is not strictly part of the Fringe, though they do have a play on during this period. Unlike the vagabonds, the fly-by-night groups, the one-off soloists and the duets that make up the bulk of the Fringe, Red Stitch has been around all year–though that is as long as they have been around and where they appeared from and how and why is a mystery. They are an actors’ group with no resident director, which sets them apart from most of the other groups that have emerged recently in Melbourne. This means that the focus in the choice of material seems to be to provide solid, meaty acting experiences for those in the cast. They put out the feelers for directors and have had almost as many as the number of plays they have mounted. Their commitment at the start of the year was to present 15 new shows in the first year. This is an enormous task for a non-subsidised group but they are keeping to their promise and by the time I saw their show in September they were up to their 10th–of which I have seen 4.

Psychopathia Sexualis by John Patrick Shanley is, if it is fair at this stage to so define them, a typical Red Stitch show–contemporary, urban, neurotic characters caught in a situation which confronts them sexually, socially, psychologically, a sort of black comic dark night of the soul. Except that on this occasion there isn’t much soul. The performances in Psychopathia Sexualis are relentlessly large; too large I think for a space as small as the company performs in and for an audience so close. It is as if the thinness of Shanley’s script draws from the performers the need to overcompensate, to give the audience the hit that they have come for, through the sheer weight of performance energy. At times this provides moments of delightful modern grotesquery but overall there is a sense of unnecessary expenditure of energy to little purpose. The fault lies not so much in the production as in the material chosen. Red Stitch is charting a path down the middle of Off-Broadway. I wonder if this path will lead them very far. They have their audience’s entertainment firmly in mind. But with actors as strong as these, a lot more thought could be given to the quality of the work chosen. They need to really get their teeth into something. From all reports, the following play, Howie, aims to do just that.

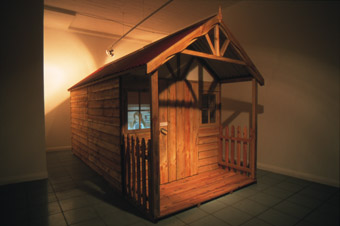

Red Stitch performs in a small space in St Kilda–a converted office or small factory, I presume. James Brennan and his company GoD BE IN MY MouTH choose even more marginalised spaces. Last year’s Piglet (the winner of the best Original Work in the 2001 Fringe) took place in Brennan’s inner suburban garage, converted for the occasion. The venue for this year’s The Glass Garden–upstairs in an old Bakery in West Melbourne–was so off-limits that we had to receive directions by phone (which adds to the mystery of course). The completely non-theatrical nature of the spaces suits Brennan’s work, which opens the door to the magical from within the fabric of the everyday. Brennan wrote, directed and took the central role in both works. They were vehicles for his fearless and unique performing talent. In him, the artist and the child fuse. He enters the world confronting him with all the awe, curiosity, fear, trust, joy and vulnerability of a young boy, but the edge of his performance style, its wit and its wisdom, are not simply childish. In Piglet, his guide and companion was a stuffed piglet toy. At the end of his pier, he caught in his net an entrancing, serpentine woman. He was duly entranced and transported into a Wonderland nightmare of cotton wool and fatness, where the woman became his adversary and the toy his sacrificial victim. Words cannot do justice to the sheer transformative power this show possessed. It was a gem, perfect in its pitch and exhilarating in its access to the creative spirit.

The Glass Garden is also about a journey. Confronted with the news that he has breast cancer, the journeyer leaves his job in a bookshop and is gradually drawn into a world without definition where, as he says, in his childlike attempt to understand it all, the signifiers and the signified do not match. The tree you are looking at may not be the same thing that I am looking at, may in fact not even be a tree. Again his seducers are women, mute but physically expressive. Here they are guides as well as seducers. Quite where we are left at the end of The Glass Garden is unclear. This is the first part of a trilogy. I could have done with some of the quality of verbal text that so enhanced Piglet. This one felt too dependent upon spacey movement, music and smoke. But when Parts 2 and 3 emerge, I’ll be there, ready for another disturbing dose of GBIMM witchery.

Finally, a group of Melbourne’s best improvisers (Impro Melbourne) presented 2 nights of long-form improvised Shakespeare. That’s right! One hour of spontaneous iambic pentameter, rhyming couplets to end the scenes, and in particular, a deep and witty understanding of how the unfolding structure of a Shakespeare play is the skeleton upon which any tragi-comic romance of lords and ladies can be hung. The night I went, the wittily suggested title from an audience member–Blind Venetian–set the group of 5 off into an intrigue of physical deformity, the transformational power of courageous love and the revelation that the princess’ physical ugliness was but a manifestation of her parents’ moral turpitude. It was apt that the highlight of a ‘high’ evening came when one of the actors mistakenly referred to the princess he was wooing by the name of a former lover. Then both ‘he’, the actor, and ‘he’, the character, were truly at one, engaged in an act of survival in iambic verse, while the audience and princess awaited with barely hidden hilarity the success of his endeavour. What we are witness to in theatre like this is the fallibility and criticality of every moment on stage and the sheer miracle that anything gets on at all in this raw laboratory for the power of the creative.

Psychopathia Sexualis, Red Stitch Actors Theatre, by John Patrick Shanley; director Janice Muller; Red Stitch Space, Sept; GoD BE IN MY MouTH, The Glass Garden, writer, director, performer James Brennan; music UBIN; with performers Patrick Brammall, Mia Hollingworth, Brooke Stamp; secret location, Sept 25-27; Impro Melbourne, Nights of Contemporary Theatre, improvised Shakespeare, directed by Kate Herbert, Carlton Courthouse, October.

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. web

© Richard Murphet; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Melbourne Fringe 2002 had a strong music and sound program. The Ennio Morricone Experience for example was presided over by new music champion and playful percussionist Graeme Leak and trumpeter cum smooth, Hispano-lounge raconteur Patrick Cronin (Texicali Rose), who enlisted seriously mugging bass-player Daniel Witton (Desoxy, Blue Grassy Knoll), orchestral percussionist David Hewitt and pianist/oboist Boris Conley.

A doyen of 20th century musical avant garde-ism, Morricone scored everything from The Mission to Once Upon a Time in America and the Mediterranean schlock fields of Spaghetti Westerns–most famously the Sergio Leone/Clint Eastwood trilogy. Although eccentric favourites like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly were featured, Morricone’s 1960s-pop title-songs were also resuscitated (sung with tongue-in-cheek passion by Witton). These were punctuated with games involving both abstract or eerie sound effects and directly representational ones (Witton sounded out a hiding gunslinger using baby Blundstones on sand, while Cronin strode about with aggressive, amplified-Cornflake-crunches as the Man With No Name).

Leak and Hewitt employed inventive instrumental transpositions to amplify the dry yet active humour of their creative interpretations. Leak’s trademark homemade “string-cans” appeared, as did a bowed-saw. The choreography of multiple instruments was often dazzling (Leak mastered an extended drum-kit, whistle, hand-bell, chimes, drum-pads, and vocal “hoo-hahs!”, all in 2 bars). Restrained comic understatement reigned throughout, paradoxically enhanced by Witton’s uniquely exaggerated facial expressions. Minor gestures and nuances thereby became highly charged, conveying the performers’ idiosyncratic characters through minimal means. It was like peering through glass into a 1960s recording booth at a group of eccentric musicians amusing themselves between takes.

Margaret Trail meanwhile voiced poetico-sonic musings on the alluring shadows that lie beneath our superficial culture. Four Nights in a Dark Room employed text, performance art, sonic-layering and free jazz in a fashion whose best known precedessor is Laurie Anderson (a sample of whom was hidden within the soundscape).

Lunar transformations, lycanthropy and wolf symbolism provided Trail’s thematic foci. In a closely measured yet remarkably unaffected style, she related tales of the unknown creeping into daily banalities. Trail eschewed the precise gestural vocabulary which underscored her earlier work, K’Ting! (2000), preferring here a simpler physical presence to support the evenly paused, rhythmically open, spoken-word and recorded text. We heard the story of a bizarre break-in, in which thieves stole her wolf recordings, and the subsequent police investigation, leading her friend to conclude: “We’re in a horror movie! This explains the full moon, the disappearance of your werewolf sounds and the unusually attractive police.”