Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Ryk Goddard

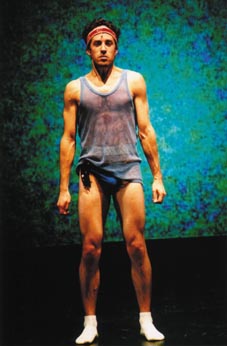

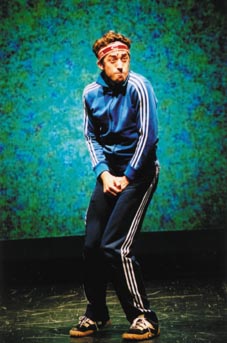

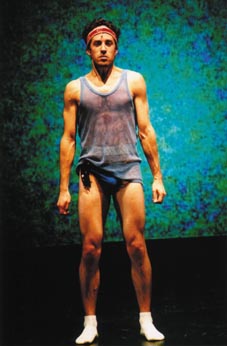

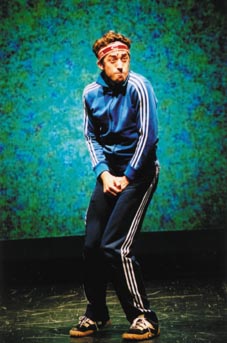

Ryk Goddard worked with Melbourne’s the accidental company receiving critical recognition for works like Imagine a Life, superfluous man, Teapot and Fifteen Words or Less. He was appointed Artistic Director of Salamanca Theatre Company in 2000. This company, established in 1972, has a reputation for theatre excellence and innovation, most recently under the artistic direction of Deborah Pollard, producing over 100 contemporary theatre works for young people. Since Goddard’s appointment, Salamanca Theatre Company has changed its name to is theatre ltd. Promotional material for is theatre can be read as both a statement of intent and a question: is theatre: experimental, is theatre: site specific, is theatre: improvisation.

Can you comment on the name change?

is theatre ltd reflects our new role in Australian Theatre. Thirty years of theatre in schools has not produced new generations of theatre-goers. Another reason for the name change was that people couldn’t distinguish us from the Salamanca Arts Centre. The new name positions our company as always questioning itself and the ways we develop, promote and present performance experiences.

What do you understand by contemporary performance?

Contemporary performance is happening now. It’s work that is made by people in a particular time with an intention that’s relevant to that time. Whether it’s text-based, experimental or devised, my sense of whether it’s contemporary or not is to do with the intention in making the work. All new work or experimental work is supposedly contemporary. I live in permanent fear of contemporary performance trying so hard not to be things, that it ends up not really being anything at all. The result is work that can be amazingly insipid and lacking in courage and vision.

We’re not performing shows in schools any more. Our research and engagement with young people indicates that participation is as important as watching. is theatre is shifting philosophy and practice away from theatre-in-education to a contemporary performance practice that moves away from serving schools to serving young people. We are working directly with students in schools through participation and putting on outside shows that young people can come to. What’s desperately needed in Tasmania is things for young people to do that are relevant to them, and in spaces where they have a sense of ownership.

We’re aiming to present work where the given is the environment. With Freezer we wanted to enhance and expand people’s expectations of the dance party environment. A dance party is an existing valid culture. There are powerful dynamics in the space that are really interesting. We wanted to align ourselves with that and open it out further. I like work where the artists have to work hard for the audience to have an interesting experience. That makes the world bigger, richer and experienced in a new way.

Blink, Eat Space, Fashion Tips for Misery, Boiler Room, Freezer, flip top heart and am.p are names you’ve devised for theatre training programs, improvisation laboratories and site-specific performances in 2001 and 2002. What future projects excite and push your boundaries as Artistic Director?

In the biggest sense I’m excited that I finally had the courage to place my performance practice at the centre of the company. Everything we do is connected in some way to improvisational practice. This main-streaming of improvisation seems to be happening everywhere and I feel in step with the times. White Trash Medium Rare is the first show I’ve done for years where I fully understand why I’m doing it. It’s a performance installation supported by Australia Council New Media Arts funding. We’re looking at issues of white identity and every artist involved has their own voice and their own practice.

At the end of July I’m participating in the Improvisation Festival of Melbourne, before MC-ing Sydney’s Big Sloth at Performance Space and then performing in Canberra’s celebration of improvisation performance. Between August 22 and 25 is theatre will host Boiler Room, a participatory multi-artform event. Artists from dance, theatre, music and the visual arts will facilitate workshops and show existing work. On the final night the artists will create a performance that combines and advances their skills. Boiler Room will happen at is@backspace.

For many Hobart theatre audiences The Backspace is a familiar environment that has sustained a lot of theatre practice. You’ve been instrumental in refurbishing and revitalising it as is@backspace.

is@backspace is Hobart’s dedicated contemporary performance space. It’s a new multi-use, flexible, 100 seat performance venue. The space is available for hire to develop and present contemporary performance. You can’t innovate in a town without an audience base and space for artists. We’re thrilled because is@backspace is booked out for the next 6 months. It’s a space to nurture yourself as an artist in a low-risk environment.

is theatre, Boiler Room, teaching & performing Ryk Goddard and Helen Omand; music creation Josh Green; dance improvisation Jo Pollit; multi-media Sean Bacon; musician Tania Bosak. is@backspace, Hobart, Aug 22-25.

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 40

© Sue Moss; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Studio got off to a good start with its first 6 month program, quickly establishing itself as a popular haunt for all sorts of live arts fans—sometimes it felt like each show attracted its very own tribe. It’s generally agreed that the contemporary arts scene has been enhanced by the presence of this comfortable and accommodating venue at Sydney’s premier location and its energetic support of Australian artists through programming, commissioning and co-producing.

If volume is what it’s about, The Studio has the goods. At the launch of Program 2, the management proudly stated that while there were 92 performances between July 2000 and June 2001, by June 2002 they’d counted 173. Given that most of these were short seasons, it’s amazing that Executive Producer Virginia Hyam and her team look as perky as they do. The new program suggests no rest is in sight, save for the 5 week season of The 7 Stages of Grieving. By the end of 2002, 104 independent artists, 5 small to medium companies and 17 music groups will have appeared at the venue.

A welcome new element is The Studio’s hosting of ReelDance Dance on Screen Festival in August (preview, page 32). And while the Dance Tracks programs might have had teething problems, it’s good to see a commitment to continuity in Dance Tracks 3, this time The Studio teaming with the Breaks of Asia Club as part of the Asian Music & Dance Festival, August 14-18. (Incidentally, don’t miss the visit by the acclaimed Akram Khan Company from London who’ll be performing their work Kaash at the Drama Theatre for the festival, August 20-24). Later in the year, in Dance Tracks 4, guest musicians are Endorphin and French DJ, BNX.

It’s great to see a classic of contemporary performance given a new outing. With Deborah Mailman’s current TV popularity, The 7 Stages of Grieving should be huge. Same goes for Donna Jackson who impressed with her Car Maintenance Explosives and Love at Mardi Gras a while back but hasn’t been seen in Sydney since. Her Body: Celebration of the Machine is part of the cultural program for the Gay Games. Hanging onto the Tail of a Goat created and performed by Tenzing Tsewang (RealTime 43) is a small but significant work originally previewed at Performance Space, premiered at Melbourne’s Gasworks and now given a welcome Sydney season. Premieres include Legs on the Wall’s foray into the primal world of sport, Runners Up, and Wide Open Road a collaboration between 2 youth theatres, Sydney-based PACT and Outback, based in Hay in south-western NSW.

The Australian Composers series features the work of 2 contemporary artists. Drew Crawford presents Lounge Music, an intimate evening of works chosen from his theatre and dance compositions, electronic works, opera, cabaret and concert music. And in Over Time Andrée Greenwell orchestrates her engaging collision of popular, experimental and operatic musics.

There’s jazz and fusion and some top notch stand-up in the form of Sue Anne Post (G Strings and Jockstraps) and Lawrence Leung (Sucker, winner Best Solo Show, Melbourne Fringe) and some quality acts in the exhibition space including Christopher Dean, Clinton Nain (responding to The 7 Stages of Grieving) and Mikala Dwyer.

As with Program #1 there’ll be hits and occasional misses in Program #2 at The Studio, a lot of creative risk-taking, and plenty to argue about afterwards at the ever inviting Opera Bar. Importantly, it’s all presented in a spirit of generosity and celebration of Australia’s contemporary culture. RT

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 40

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

You get your first job after drama school and you’re told, ‘Remember your lines and don’t bump into the furniture.’

Anonymous actor

The craft of the actor has been nurtured in Australia for the past 20 years by a number of tertiary institutions. The National Insitute of Dramatic Art (NIDA), West Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA), Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), Theatre Nepean at the University of Western Sydney (UWS), the Arts Academy at the University of Ballarat, and the Drama Centre at Flinders University are among many institutions that offer tertiary training in the craft. Since these schools are relatively young in terms of the history of Australian tertiary education, their overarching vision and curricula have been formed by their staff. It is difficult to imagine the holistic and passionate approach to actor training that one finds in these drama courses occurring with the quite same intensity in other arts disciplines. Peter Kingston, Head of Acting at WAAPA, expresses it in this way: “We talk amongst ourselves every week, every day, about what we’re doing.” But how does this “productive and generous self-indulgence” prepare graduates for an acting career?

In actor training there is a strong sense of a genealogy of method, a philosophy of theatre that is passed on to students. And something else—passion. When asked about their own training, all of the practitioner/teachers I spoke to were glad of the opportunity to speak about what had ignited them, to recount the story of finding their own sense of self within the art form. It is interesting to note that all the teachers of acting I spoke to had trained at a tertiary level in drama school—some as performers, others as directors.

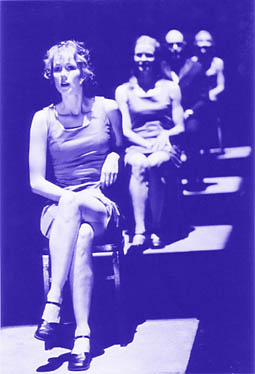

In the courses I surveyed for this article, all have a curriculum built around movement, voice, acting, improvisation, devised work, singing, film and television skills, production projects and the creation of a show reel for graduates, often with a performance day for agents. Despite the overall commitment to a ‘total approach’ to training, there are some philosophical variances within the schools. At the VCA, WAAPA and NIDA there is a cohesive approach to actor training, guided by the Head of Acting at each school. In my conversations with 7 teacher/practitioners, I was struck by the depth of their commitment to the notion of the individual’s journey through the training, in preparation for the twisting path of a career as an actor/theatre maker. This personal connection, which Lindy Davies, Head of Acting at VCA, describes as “detached intimacy”, is exemplified in the question she put to herself when she was formulating the Acting Course: “How do I create an atmosphere where people feel safe?”

Peter Kingston says that he and his colleagues strive to deal with students “in a mutually respectful way, expanding their potential and our resources inside a laboratory, a rehearsal room.” Professor Julie Holledge, Director of the Drama Centre, Flinders University in Adelaide, also describes a holistic approach to the training of actors: “It is essential that an actor’s training balances the intellectual and the expressive, the intuitive and the analytical.” Kim Durban, Course Co-ordinator at the Performing Arts Course at Ballarat University, says: “The tool of the actor is the self, and the training is to sharpen and change and challenge those qualities of self as they are applied to the materials of theatre—time, space, body, silence, word, image.”

Lindy Davies has formulated a very specific method arising from her experience working at the Pram Factory in the late 60s, and training with Linklater, Brook and Grotowski in the 1970s. While working in Peter Brook’s company, she resolved for herself an apparent conflict between the contact-release work of Linklater and the discipline of Grotowski. “The form was the key to it all—it was the crucible that allowed the other elements to happen within it.” These experiences have been the foundation of her method in the last 7 years as Dean and Head of Acting at VCA. “We have a very radical approach to acting at our school. We don’t decide how we are going to say it or do it. The interpretation comes from the actor’s perspective—it happens kinaesthetically. We work to find the bridge between trance and language.”

Peter Kingston is in his 5th year as Head of Acting at WAAPA. Having trained at NIDA as an actor, he is inspired and challenged by the task of training actors. He muses that he and his colleagues in other acting courses are essentially doing the same thing, instilling in students “the importance of collaboration and that a truthful experience shared by the people making the work is the fundamental work.” Peter is eloquent about the state of ‘not-knowing’ at which point he encourages his students to begin. “What I bring to it is all that I don’t know. The group creates a fury of private investigation which spurs the work forward.”

Tony Knight, Head of Acting at NIDA was “thrown out” of NIDA as a student in the 70s and then went on to train at the Drama Centre in London. He says that the course at NIDA is “an intensely practical course—any theory happens on the floor.” As an acting teacher he draws heavily on the later Stanislavskian physical action method, where the action is played first, with the emotional/psychological territory taking care of itself. He believes that “acting always has to have an emotional and psychological approach”, but does not have time for any emotive indulgence from his students when they approach a character.

At Flinders, Ballarat and Theatre Nepean, the courses tend to be centred round a wide spectrum of skills, and the desire to expose students to all aspects of theatre. There is also an emphasis on theory and history to counterbalance the practical training. There is a heavy emphasis on ensemble work, so that students have the opportunity to write, direct, design, source props and costumes, raise funds, promote the work, in addition to performing. Julie Holledge was trained at the Bristol University Drama Department. “I was taught that actors require both a rigorous intellectual training and a highly disciplined physical training if they are to be expressive performing artists.”

After graduating from Bristol, Holledge worked as an actor and director in the alternative and experimental theatre in Britain for 10 years before moving to Australia. Unusually, the course at Flinders is a 4-year program resulting in an Honours degree. Holledge explains, “At Flinders there is no artificial separation between the body and mind, emotion and intellect. Our degree programs prepare our graduates to be creative, articulate and adaptable artists in whatever area they work.”

The question of how to prepare students for careers as actors is a common theme for teacher/practitioners, with acting courses often forced into review by university curriculum boards. Kim Durban says, “I am currently in a time of Course Review, so I often ask myself ‘what must a training artist know?’ I know many older actors are concerned that traditional theatre knowledge is disappearing. I sometimes wonder whether the old repertory system did a better job. However, where a university course can have value is in its connection to theory and research.”

Terence Crawford, Head of Acting at Theatre Nepean at UWS, trained as an actor at NIDA, and rejects the notion of a hegemonic method. “A method can be a bit of a lifeboat for actors to cling to, rather than just being happily ‘at sea’ on stage.” He teaches his students to think critically “before and after the act, but in the act, to lose their heads.” He believes there is terrible confusion about acting methods, with actors often not understanding that a method is for rehearsal, “not for going on stage. I teach methods toward acting, methods of rehearsing. I am very wary of anyone who says that this is a method and it will apply to all circumstances. As far as I’m concerned, such people have closed the book on creativity—have lost the humility which is the key to acting.”

After graduating, Crawford worked closely for 3 years with John Gaden at the State Theatre Company of SA in the 1980s. “John exemplified for me something I have continued to explore as a teacher: the connection between basic decency and acting.” This interest in the ‘ethical health’ of the actor has stayed with Crawford as he works with his students. “Good actor training is training for life—a kind of productive and generous self-indulgence. You’re there to look at yourself and learn about yourself in order to give, in order to be generous to others, to an audience.”

What does the world require of actors now, and how are they prepared for it by the academy? Tony Knight says “Most students who graduate from film and drama courses are going straight into film and television because that is the dominant market in Australia. The industry changes so quickly. What we have to do is get them ready for how the industry is now and for what they want to do in the future. We have to help them strike the balance between being an artist and becoming a commodity.” Kim Durban believes that the focus of today’s acting students is very different to those she trained with at the VCA in the early 1980s. “When I went to drama school we ridiculed the mainstream, looked down on TV and burned to be significant/alternative/ authentic. But now I have noticed a trend of leaning towards ‘the centre’—that many young and talented arts workers yearn to be discovered by the larger companies, to cross over. They are not committed to Howard Brenton’s “petrol bomb through the proscenium arch.” A visit to the theatre is often beyond their budget, on top of petrol for a 90-minute drive from Ballarat to Melbourne, in between working to make a living. They are far more likely to be writing a film-script and producing it on the weekends.”

Lindy Davies and Julie Holledge also speak about the need to balance the artist’s identity with the need to earn a living. “Actors today need to be trained in the skills necessary to earn a living,” says Holledge, “and for the most part these are connected to television and film. On the other hand, they need to be trained as performing artists who can push the boundaries of live theatre and attract new audiences even if this work, while sustaining them creatively, will never sustain them economically.”

Tony Knight has a big and hopeful vision for his graduates: “I want them to finish their training with the eye of a poet. I want them to show us new things. The baby boomers are going and something new will be in its place and I just hope they’re ready for it.”

Despite the focus now in acting courses on ‘survival skills’ to assist the graduate as they strive to enter the industry, all the teachers I spoke to agree that something more than skills and showreels are called for. The ingredient an actor needs to survive an unpredictable career is the ignition point, the passion that their own teachers began with. Yana Taylor, Head of Movement at UWS, wishes to inspire in students what Brett Whitely called “a true love for the difficult pleasures of the artistic life.” She believes that these ‘difficult pleasures’ “give you a view that enables you to move from job to job.” It seems that what everyone is assisting young actors to find is the indefinable thing that Terence Crawford calls “faith in the self”, and Peter Kingston “the spark of genius”, and Lindy Davies “something bigger than themselves” and Tony Knight “the eye of a poet.” In the end, perhaps it is the personal vision discovered, questioned and honed as a student that gets people through an acting career, and helps them to remember their lines, without bumping into the furniture.

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 43

© Jane Woollard; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Front: Samantha Chalmers, Allyson Mills, Anthony Johnson, Steve Hodder, Michael Angus Back: Jodie Cockatoo, Shellie Morris, To the Inland Sea

courtesy Darwin Sun

Front: Samantha Chalmers, Allyson Mills, Anthony Johnson, Steve Hodder, Michael Angus Back: Jodie Cockatoo, Shellie Morris, To the Inland Sea

Having only just returned from a road trip across the Barkly, driving for hundreds of kilometres through a sea of yellow grass stretching from horizon to horizon, flat as a tack for as far as the eye could see, the notion of an inland sea is both credible and evocatively appealing.

What is not so appealing is the notion of another piece of theatre based on the heroic exploits of some misguided white male out to pit his manhood against this country’s heart of darkness, searching for a personal holy grail. This focus was obviously not behind the Darwin Theatre Company’s most recent production, To the Inland Sea, based on Charles Sturt’s ill-fated 1884 expedition. The DTC team charted quite a different trajectory across this well-trodden territory.

Conceived and written in the NT, this ambitious project was billed as “a fiction based on Sturt’s epic journey, during which he carried a whale boat on a wagon through the desert”, searching for a mythical inland sea on which to launch it. With this compelling story of folly and disappointment as a starting point, writer-director Tania Lieman, co-writer Gail Evans and Indigenous composer Shellie Morris also intended to tell the story of the Indigenous guides and traditional owners of the country being ‘discovered.’ As well. This post-colonial approach is par for the course these days in Darwin, as is the exploration of multiple histories and ways of seeing.

In To the Inland Sea Sturt’s linear, historical narrative is interlaced with a contemporary story of another lost soul, a young Aboriginal boy dealing with issues of dislocation and alienation of another kind. These stories run in parallel throughout the production, interweaving past and present, reality and dream, and interior and exterior perspectives.

A giant video screen provides the backdrop for much of the action and dominates the stage. On a huge scale, vast landscapes, endless sand dunes and flocks of birds stream past as Sturt’s company becomes ever more mired in the desert. During the contemporary scenes the landscape imagery is replaced with the face of the Aboriginal boy, filling the space with anger and pain.

This psychic link between the 2 stories is alluded to in the opening words of the play, “everyone’s on a journey”, spoken by the Aboriginal boy’s mother, sitting down painting her country. Some journeys are physical and some are spiritual. Not all lead to the goal we seek or necessarily to redemption.

Another link between the narratives of past and present is made by the chorus: singers Shellie Morris, Jodie Cockatoo and dancer/vocalist Samantha Chalmers. Morris’ beautiful and haunting music was a highlight of the production.

The usual DTC style of physical theatre dominated the more conventional narrative. There was an abundance of energy and action amid all the drama as well as choreographed set pieces such as a fictitious ‘last supper’ featuring a cast of explorers pontificating about their exploits, including a ragged Wills, like Hamlet, holding a skull.

Unfortunately as the production continued I felt I was drowning, being overwhelmed by altogether too much going on. There was never enough breathing space amid all the colour and movement and technical whizz-bangery. There were beautiful, poignant moments but too rarely the possibility of savouring them. This was a pity because otherwise To the Inland Sea was an enjoyable production with all the right elements: great ideas and visuals, energy, points of cross cultural contact and risk-taking.

Darwin Theatre Company, To the Inland Sea, Darwin Entertainment Centre, June 11-22

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 44

© Cath Bowdler; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

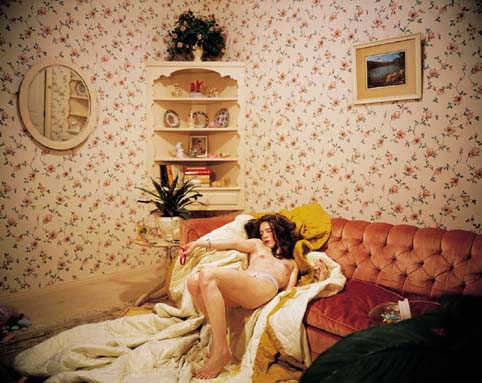

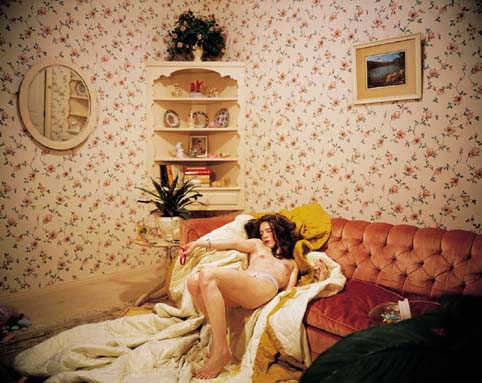

Erica Price is a solitary dreamer and i industrious sex worker whose monologues reveal desperation for companionship. Her daily musings, including a mantra that ends, “…I ask myself: Who the fuck is Erica Price? And what is her price?”, allude to neighbourhood friendships that will never eventuate for her. A motif that begins, “When the Revolution comes…” refers to all manner of improvements and happiness that the increasingly delusional Erica needs to believe in.

Some of her clients are in love with her, some are self-absorbed, but they still want her reassurances, or her platitudes, for that is all she offers them. All 7 male clients are played by Lucien Simon, who is able to imbue each with a distinct persona. He conveys the hypocrisy and selfishness of several of these characters with particular skill. Subtly and empathically played by Marisa Mastrocola, Erica is vulnerable and determined, funny and sad as she descends into disillusionment bordering on the catatonic.

With Mastrocola’s pose and body language at the play’s conclusion exactly as they were at its beginning, director Tania Bosak implies that the action has come full circle. Erica is back at square one, having achieved nothing, and still longing for a life that will never eventuate. This confronting play could easily become too bleak but, finding moments of comedy, director and performers hit the right note.

Scape Inc., Who the Fuck is Erica Price, writer Sarah Brill, director Tania Bosak, Peacock Theatre, Salamanca Arts Centre, June 20-29; Carlton Courthouse, Melbourne, Aug 7-17.

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 44

© Diana Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Border Project, Despoiled Shore MEDEAMATERIAL Landscape with Argonauts

The fallen-from-grandeur blend of architecture and streetscape of the historic Queen’s Theatre offered an apt historical and geographic metonym for the performance of Despoiled Shore MEDEAMATERIAL Landscape with Argonauts. Derived in part from a text by GDR playwright Heiner Müller, MEDEAMATERIAL is the latest production from a theatre ensemble of Flinders University Drama School graduates calling itself The Border Project. According to program notes, the ensemble aims to chart and map the future language of performance by exploring the interface between live performance and multimedia technologies, thus testing the boundaries between audience and performer.

While some familiar with the draughty venue and its hard platform seating came with cushions, woollen blankets, gloves and beanies, others caressed their glasses of Hardy’s in an effort to keep warm in the cavernous void of a minimalist performance space designed to represent “an urban wasteland where humankind has decimated and abused the natural landscape.”

More physical challenges were to come. The relentless amplitude of synthetic music beat incessantly, producing a searing soundscape like a techno time clock ticking towards death. It raked the skin and tore into the wrecked recesses of consciousness. The complex, cerebral text interfused references to the globalised technoculture of American popular culture (the banality of basketball and Big Macs) with a condensed version of Euripides’ Medea (the ominous effects of power, jealousy, betrayal and violation). These segments fused into a middle space of comic relief, referencing the disappearance of Azaria Chamberlain and giving a luminous, stuffed dingo central positioning on stage in a darkly comic, John Clarke-inspired interview (with the dingo).

The final segment segued from the shadows of German expressionism and film noir to the decimated landscape of modern times. In the last scene, Jason, our damaged argo/astronaut, emerged from the void as television monitors flashed NASA film clips of the explosion of the Challenger space craft. All this, from Greek tragedy to 20th century eco-disaster, in 45 minutes.

The technically adept performance had its strengths. Particularly well realised were the enactments of actors’ identities and desires as the extensions of television images, as well as the evocation of a theatre-of-death psychic landscape rendered through the menacing music, the cacophony of accents, and the pastiche of images from German expressionism. The performance lost some of its impact to screeching sounds, halting, overwrought and sometimes frenetic speech and pronounced breathing of the actors, and the near hysterical pitch of sound and media landscapes in the final segment. The company holds more promise than it delivered in this instance.

The Border Project, Despoiled Shore MEDEAMATERIAL Landscape with Argonauts, writer Heiner Müller, director/designer Sam Haren, performers: Katherine Fyffe, Cameron Goodall, Ksenja Logos, David Heinrich, Amber McMahon, Paul Reichstein, Alirio Zavarce; Queens Theatre, Adelaide, June 20-29

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 46

© Kay Schaffer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Narelle Autio, Not of this Earth

courtesy the artist

Narelle Autio, Not of this Earth

Sydney University’s Sir Hermann Black Gallery is currently hosting an exhibition of works by notable photographers working the documentary format. A collaboration with Stills Gallery, the exhibition showcases a wide range of approaches to the form. One image is chosen to document the work of artists who more usually exhibit in series or essay form, among them, Ricky Maynard’s huge and confronting portraits of Wik elders; Stephen Lojewski’s suburban enigmas; Ella Dreyfus’ stark depiction of a body in transition from male to female. Trent Parke is a remarkable young photographer who’s recently be accepted into the Magnum Photo Agency for a one year trial period before final nomination, the first Australian photographer to get the nod. His Dream/Life series is represented here with a luminous image. Also featured is Narelle Autio’s photographic poem to leisure, Not of this Earth depicting richly coloured and textured aerial views of people relaxing beneath Sydney’s Harbour Bridge. In all there are 19 great photographers including William Yang, Lorrie Graham, Jon Lewis, Peter Milne, Donna Bailey, Jon Rhodes—every one of them worth a look.

RePRESENTING the REAL, Documentary Photography 2002, Sir Hermann Black Gallery & Sculpture Terrace, Sydney University till 17 August.

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 14

© Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In response to considerable demand, our annual feature on the teaching of the arts in tertiary education has been expanded significantly this year to cover 8 artform areas—music, sound art, visual arts, film, new media, dance, theatre and contemporary performance. We’ve decided to focus on the training of the artist at a time when issues abound about proliferation of courses, competing methodologies, limited job markets and the commercial challenge to art’s integrity.

The essay on visual arts aside, where the issue of what art schools really do is tackled provocatively by Adam Geczy, our reports survey the practical training courses Australian universities have on offer. Our writers have interviewed lecturers, many of them also practising artists, about their teaching. Sometimes they speak on behalf of their schools, sometimes about their own practice.

It was clear from many of our respondents that limited funding, escalating class sizes and threatened course closures continue to be a serious challenge to staff morale and the effective training of artists. However, our focus is largely on what the various schools offer regardless of the conditions under which they operate.

There are a number of trends that emerge in these reports, some have been with us for a while, some are new, all are reaching new levels of intensity. Almost across the board there is a desire to generate in students the capacity to collaborate, for both the practical and ethical advantages of cooperation (even in feature filmmaking where the ideal of the auteur has persisted for so long). Autonomy rates highly, not as individualism but as the capacity to be self-sustaining, to create work alone or in teams rather than waiting to be employed. Not a few courses promote adventurousness, in terms of keeping up with new developments or in challenging convention. And in an era when artforms are transforming and electronic media converging there is a great emphasis on flexibility and multi-skilling.

Some departments pride themselves on having industry connections, on being part of network clusters, of providing in-course opportunities to students in the commercial world. It is here that some tension is felt over the apparent pragmatism of the “creative industries” approach as art gives way to the broader notion of creativity, and the demands of commerce, for example ‘to entertain’ or provide ‘content’, threaten to dominate. Conversely, commercial and subcultural developments in the wider world of music require an academic response, as Michael Hannan argues, that recognises there will be a variety of serious musician for whom traditional training will have little value. This adjustment is symptomatic of a wider phenomenon, the evolution of artforms and, particularly, their engagement in multimedia and new media. If some lecturers ask that their students learn to “sit with ambiguity” as part of their becoming artists, then the ambiguity that surrounds artform developments is something that teachers also have to sit with.

While most schools claim good employment results for their students, the jobs issue is nonetheless a vexed one, particularly in visual arts and dance. Our report notes the global approach to employment by at least one Australian university dance school given the almost total lack of work available in this country.

Whatever the challenges, many lecturers spoke with passion about their teaching and their concern for their students. There’s a desire to create a safe place in which students are emboldened to think, to create, to collaborate, to accept challenge and, in turn, to challenge.

The death of a dancer: Russell Page

In a year already too burdened with artist deaths, we were deeply saddened to hear of the passing of dancer and actor Russell Page on Sunday July 14. We saw him dance a few days earlier in Rush, the work his brother Stephen choreographed for Bangarra Dance Theatre’s new program, Walkabout. As ever, Page danced with conviction, elegance, power and a unique dancer’s language. He will be missed. KG VB

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 3

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Total Masala Slammer, Heartbreak No 5

At last Melbourne has got a festival where local artists—there’s a lot of them in the program—receive deserved prominence side by side with some unique overseas and interstate productions. It’s the first of Robyn Archer’s 2 Melbourne Festivals. The second will be about the body—in dance and physical theatre. Perhaps she’ll get the guernsey for a third festival given that she’s already forecast it to be about voice, as in opera and music theatre.

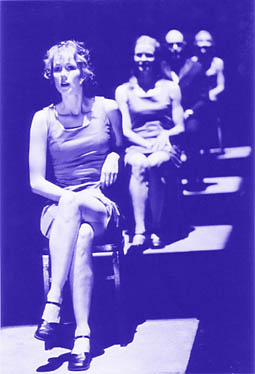

This one is centred on text ie language in performance. If you’re expecting a season of nice plays, forget it. Archer’s choices and her vision of text in performance are as wide-ranging and provocative as you’d expect from her Adelaide Festival programs. She deals a blow to the myth that postmodernity has been the ruin of language. Here it comes embodied in dance, puppetry, music, physical theatre, installation, multimedia, contemporary performance and, yes, plays, but what plays! From Berlin’s Hebbel Theatre comes Total Masala Slammer, Heartbreak No 5, an erotic adaptation of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. There’s The Fortunes of Richard Mahony, adapted by Michael Gow from the novel (QTC/Playbox), and the Pinter version of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past (VCA). The profoundly disturbing, not-to-be-missed Societas Raffaelo Sanzio make their first Melbourne appearance with Genesi, from the Museum of Sleep. Ivan Heng’s 140 minute solo performance about power and gender, Emily of Emerald Hill (writer Stella Khon), comes from Singapore. The 150 minute virtuosic adult marionette work, Tinka’s New Dress, has Ronnie Burkett creating and voicing 37 characters. Argentinian writer-director Frederico Leon presents one of his plays and a mini festival of recent Argentinian cinema. A handful of very intimate performances designed for small audiences include the Canadian STO Union & Candid Stammer Theatre’s Recent Experiences, 3 works by US actor-writer Wallace Shawn (My Dinner with Andre) performed by local actors, and IRAA Theatre’s Interior Sites Project, an all night stayover theatre experience. Gertrude Stein’s Dr Faustus Lights the Lights (St Martin Youth Arts Centre) gets a rare airing, and Daniel Schlusser, Evelyn Krape and sound artist Darrin Verhagen take a tough new look at Medea. And there’s more, from Five Angry Men, The Keene/Taylor Project, NYID, Chamber Made Opera, Back to Back Theatre, Company in Space, Arena Theatre Company, Joanna Murray-Smith & Paul Grabowksy, Helen Herbertson, Trevor Patrick and work-in-progress showings from others.

From Sydney comes Kate Champion’s impressive dance theatre work Same same But Different and Sandy Evan’s Testimony, a powerful and beautiful big band, multimedia tribute to Charlie Parker to a libretto by Yusef Komunyakaa. From Berlin there’s Uwe Mengel’s murder mystery installation, Lifeline, where you can become an active investigator. From the Kimberley region of Western Australia comes the passionately debated Fire, Fire Burning Bright; premiered at the 2002 Perth Festival it’s the story of a massacre presented by an all-Indigenous cast. There’s also a visual arts program (featuring Susan Norrie and Nan Goldin), a National Puppetry & Animatronics Summit and a timely national symposium on “The Art of Dissent.” In the past there have always been a few shows to draw interstate visitors to a Melbourne Festival, but this time you can feel the pull of the whole program, a unique opportunity to see an impressive display of Victorian performance talent in the context of distinctive and provocative international productions and a theme of the reinvigoration of language in and through performance.

Melbourne Festival, Oct 17-Nov 2. www.melbournefestival.com.au

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

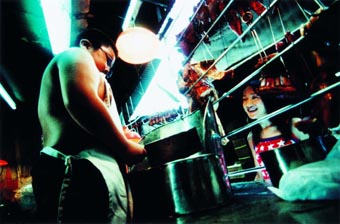

Wendy McPhee, George Poonkhin Khut, Nightshift

Dancer Wendy McPhee and film/sound artist George Poonkhin Khut share an interest in sexuality and memory. They began their collaboration on their new work, Nightshift, by looking at peepshows, karaoke bars and feminine desire. McPhee says: “I wrote a lot of the text. George designed sound and the installation environment. The meeting point was the medium of video. The bulk of the work is in the editing and sound design. We did one video edit together but we had 7 hours of material which is a lot of looking at yourself! My main concern was that the emotional quality of the performance be kept and not dissolved. I think it’s a very intimate installation even though the images are projected floor to ceiling throughout a vast space. The intimacy is reinforced via the soundscape which evokes a closeness of whispers, pulses and floating sounds of bar room singing.”

Nightshift Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery July 13-28; Artspace, Sydney Aug 22-Sept 14

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg.

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Michae Riley, Cloud 2000 (detail), inkjet print, 125 x 86cm

Michael Riley (Wiradjuri/Gamilaroi people) is one of the most idiosyncratic and inventive of contemporary artists. He explores Indigenous issues in non-literal ways, working through curious juxtapositions that make us look at the Australian psychic landscape in new ways. Riley’s distinctive body of photographic and film works will be celebrated at the fourth Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art at Queensland Art Gallery opening in September.

Asia Pacific Triennial 2002 focuses on a number of artists who have made significant contributions to the contemporary arts internationally since the 1960s and each will be represented with a comprehensive group of works. Says gallery director Doug Hall, “The exhibition creates a context in which we see works by these senior artists, alongside artworks dealing with similar ideas and themes by other regionally significant, but lesser known artists.”

Artists to be represented are: Montien Boonma (Thailand), Eugene Carchesio (Australia), Heri Dono (Indonesia), Joan Grounds (USA/Australia), Ralph Hotere (Aotearoa New Zealand), Yayoi Kusama (Japan), Lee U-fan (South Korea/Japan), Jose Legaspi (Philippines), Michael Ming Hong Lin (Taiwan), Nalini Malani (India), Nam June Paik (South Korea/USA), ‘Pasifika Divas’ (Pacific Islands and Aotearoa New Zealand), Lisa Reihana (Aotearoa New Zealand) Michael Riley (Australia), Song Dong (China), Suh Do-Ho (South Korea/USA) and Howard Taylor (Australia).

Hall comments “The selection of artists reflects key themes, including the impact of the moving image on the visual culture in the 20th century, the persistence of performance as a key form of cultural expression in contemporary art, and the capacity of contemporary art to explore the complexities of globalisation.”

–

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 13

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

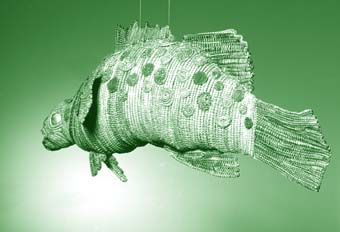

Leigh Scholten, Promotional Use Only, interactive DVD

The survival of the term ‘new media’ confounds the 20 years the technology has been around in art and design departments of the tertiary sector—the term survives possibly as the ‘old media’ users resist a technology with which they are not comfortable thus prolonging the redesign of courses and the redefinition of tertiary education within the era of digital media. The AFC/ABC on-line documentary broadband initiative recently demonstrated that government cultural administrators still think it’s a matter of converting filmmakers to ‘content providers.’ Though the education industry is at last moving away from imposing such conversion upon the mature student, it is the younger students who are often best equipped to absorb the potential of digital technologies and utilise them outside such notions of educational progression.

In an attempt to harness the many, often conflicting possibilities of information technology, there has been an exponential growth in public and privately funded tertiary level courses and subjects, particularly in arts, design, information and communication departments over the past 10 years. Only some of the issues are discussed in this article. Marketing courses, until the dot com bubble burst, had not been difficult and the income from overseas fees formed the financial bedrock of many an enterprise.

For many reasons education has more recently become accepted as a lifelong process affecting all those who care about extending their knowledge of the world and even acquiring new skills, experiences and thoughts about it. The formal system of subjects, courses, assessments and qualifications have been augmented by centres, institutes and various research units to attract the validated research dollar as part of the dynamic development of a technology and arts practice still possessing the properties of the rhizome.

Innovation

Hybridity is increasingly encountered in the arts, and in the convergence of previously distinct communication industries. With such a flux, how do tertiary media arts course managers strike a balance between providing vocational skills and developing creative and aesthetic options within the contemporary discourses of commerce, design and the fine arts? Where providing competency training has been widespread, incorporating recent technologies into existing courses and curriculum has marked the secondary stage of realising digital medias’ specificities.

Martyn Jolly, Head of Photomedia at the ANU School of Art in Canberra says, “We have tried to integrate the teaching of new technology as quickly and as closely as possible into our existing curriculum. The distinction between the ‘traditional’ and the ‘new’ means much less to our students than it does to us. Specific vocational skills are redundant in 2 years. If you teach new technology ‘workshops’ isolated from the rest of the curriculum, you end up with really clichéd, superficial gee whizz results.”

Josephine Starrs at Sydney University’s College of the Arts aims “to familiarise students with the language of new media arts, some history of the area and the contextualisation of interactive media within screen culture.” A broad approach to the subject in the tertiary sector usually includes a general first-year introduction to the visual arts, then becomes more focussed as options and electives are taken, as course strengths are identified. Starrs says that “students are asked to give seminars on current trends in digital cultures incorporating virtual communities, tactical media, mailing lists, moos, computer games, and internet radio. We examine different conceptual approaches to making use of the ‘network’, including issues to do with browsers, search engines, databases, shareware, social software and experimental software.”

At the Faculty of Arts, Victoria University, Sue McCauley and Michael Buckley “do not tie course content to industry requirements as these are constantly changing. Rather we try to get students to critically engage with content issues for specific projects…industry placement for final year students is a part of the academic program.”

The new Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology indicates the pedagogic direction now beginning to show using teaching technique and program innovation specific to the perceived potentials of digital media. Keith Armstrong, a freelance multimedia and multiple-media producer and artist, lectures in the Department of Communication Design where the broad curriculum, as opposed to the mouse-jockey paddocks of the computer labs, is likewise central to the program, but with performance added. “We draw widely upon multidisciplinary sources and get the students off their computers wherever possible, lead them through simulation games and exercises set in contemporary environments. For narrative-based works we model through role-play where possible and development through interpersonal dialogue.”

“We insist on lateral approaches, reward risk, develop marking schemes that take account of short term failures…a potent means for making students realise their deeply important role as designers/artists working within communities evolving within designed environments… [We] insist they can write text fluidly and cogently, persuade them that reflection is almost always a vital design tool, [teach them to] recognise, critique and steer well clear of multimedia’s endless seas of entrenched clichés…[and] force deceleration so that they can listen and reflect more effectively and work slowly towards ideas of substance.”

The School of Visual Arts, Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts within Edith Cowan University is perhaps an appropriately named setting for a wider reappraisel of the approach required. Students are regarded rather more as researchers who bring with them a vision and, in collaboration with the department, develop it employing what the head of school, artist Domenico de Clario [see page 37], describes as a “perceptual matrix”, encouraged during the early part of the course. Design, installation, sound and video then form the mentored streams into which the cohorts move, having access to a shopfront gallery in downtown Perth which, in accommodation above, houses an artist-in-residence. As with several other institutions, cross-overs with Information Technology and Multimedia faculty courses are being carefully negotiated, as well as closer links with community groups and the facilitation of community services, de Clario having acquired a old cinema building 2 hours out of the city.

Resources

Is it a constant fight to retain a workable budget? “Yes, yes, yes!” was the reply from one of the teachers, as all areas and departments skate the peaks and ravines of the bean counters’ graphs. Alisdair Riddell of the Australian Centre for Art and Technology at ANU, while supporting cross-departmental sharing of subjects, has great difficulty meeting the demand that this creates. Most faculties have specialised marketing officers to promote what is on offer as well as seek out what prospective students are prepared to pay. “Relatively speaking, income from overseas students allows access to good equipment” is how another correspondent described it, though the interests of the students in this area, following some disgraceful scams, are now protected by the CRICOS Provider system and new Commonwealth legislation.

“One of the greatest challenges in integrating new technologies into current pedagogical practices is explaining to those in control of budgets that the technologies classroom is inevitably more time-consuming and expensive than the format of lecture/tutorial.” Lisa Gye, Lecturer in Media and Communications at Swinburne University of Technology goes on to point out: “For example, in a number of subjects I teach, students engage in a moderated discussion list about new technologies. Most academic workload models are not designed to account for the time that is spent reading and responding to such a list. Last year, the group discussion for Issues in Electronic Media averaged 30 posts a week with each post running to approximately 300 words. Until workload models do reflect these changes, academics are going to continue with pedagogical strategies that are less time-consuming, like essay production, regardless of the relevance of the strategy to the content of taught material.”

Research grants and graduate fee income help support on-going postgraduate programs and the creation of a cultural area within the Australian Reasearch Council (nonetheless tied to the long-standing traditions of ‘investigation’ in science circles) have begun to increase the options for the development of digital media methodologies.

Antagonisms

Ted Snell is the Chair of the Australian Council of University Art and Design Schools (ACUADS) and in a recent advertising report he states that for some graduates “…their degree provides direct access to a range of professions such as design, fashion and the new (sic) digital technologies. Each year these new graduates leave art and design schools with the skills to contribute to the economy and to maintain their on-going redefinition of our community.” The arts, it seems though, still need champions. Following some recent comments made by the Prime Minister, Snell goes on to conclude that “We are fortunate that they now have the trenchant support of our senior political leaders…”

Though faculties or departments in institutions have been encouraged over the years to seek links or intern arrangements with commercial companies or not-for-profit cultural centres, it is within cross-media teaching centres rather than places of employment that the breakdown of barriers between vocational and non-vocational pursuits exist.

Martin Jolly argues that “art and commerce are no longer antagonistic—they closely inform each other. The distinction for our students is much less relevant than it is to us. But it is always hard to get commerce interested in what we are trying to do because they are working on really tight margins and struggling to keep up, just like us.” Keith Armstrong is wary: “Of course there shouldn’t be and aren’t antagonisms [but the] constant push for ‘entertainment’ as a key goal within outcomes and the sidelining of art as a viable vehicle for research [has] something to do with a lack of understanding of the histories and convergences of art and media practices.”

Mike Leggett is a curator and artist currently teaching Media Arts at UTS. UTS’s Megan Heyward was interviewed in RT#49.

Image note: Student director Leigh Scholten, worked with 27 fellow students under the guidance Helmut Stenzel, University of Ballarat, to make Promotional Use Only, an interactive CD which won the Gold Medal, Art Directors Club 81st Annual Awards, New York 2002.

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 25

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

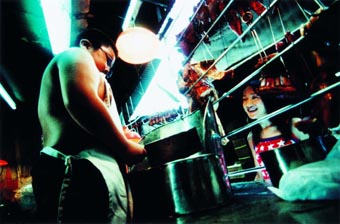

The Brisbane and Melbourne International Film Festivals consistently feature strong lineups of new films coming out of Asia as well as retrospectives (see “The ferocious eye of Kim Ki-duk”). In Sydney, fortunately, we have the Sydney Asia Pacific Film Festival, now in its third year, a relatively small but tenacious and ambitious festival whose goal is not only to open up Australian audiences to Asian films but also, laudably, “to promote the professional development of Asian Australian filmmakers and actors and their presence in the local film and television industry.” Launching this year’s festival, Sharon Baker from the Film and Television Office of NSW (FTO) reminded us that the FTO had been involved in a visit to China by 20 filmmakers and, also, that the Australian feature film, Mullet, had won Best Direction at the recent Shanghai Film Festival. The time is ripe for joint ventures and growing cross-cultural awareness. This year’s SAPFF features 15 films from 9 countries and includes a new print of Peter Weir’s The Year of Living Dangerously. Festival-goers also get the first Australian sighting of Zhang Yimou’s Happy Times. As Festival Co-director, Juanita Kwok, advised us it’s a substantial change of direction from the filmmaker’s historical approach to Chinese life. This contemporary drama borders on whimsy in its fable-like construction but its sharp social observations about dreams and realities in a newly capitalist society bring it to a complex ending. Although the focus is on film from China, others range from full-on Bollywood (Heart’s Desire, partly shot in Sydney), to a Thai western, animation from China and Hong Kong, a Vietnamese reflection on war, Japanese avant garde director Takashi Miike’s Dead or Alive 1 & 2, and the first new Australian film in this festival’s brief history, China Take Away, Mitzi Goldman’s account of writer and physical performer Anna Yen’s family life. The Short Soup film competition includes finalists from across Asia and Australia, and 2 seminars on Australia/Asia co-productions and the pressure to go mainstream and desert one’s origins promise timely debate. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle is the festival’s special guest—Gallery 4A will exhibit his photomontage works. This is a rare opportunity for Sydney audiences to participate in the growing Asian-Australian film dialogue.

Sydney Asia Pacific Film Festival 2002, Directors Juanita Kwok, Paul de Carvalho, Dendy Cinemas, Martin Place, Sydney, August 8-17.

RealTime issue #50 Aug-Sept 2002 pg. 24

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Visionary Images, Glowshow

The best thing about the 2002 Next Wave festival is that it lives up to its name. It’s rich with a present tense sense of a confident culture (often defying the youth label with very adult responses to the world) but moreso of a future tense of possibilities and potential, most evident in the proliferation of multimedia, new media, sound and site works, with very few conventional artworks or performances in sight. This is a Next Wave springing from a coherent vision which is not surprising given Artistic Director David Young’s background as composer and creator of innovative multimedia music installations and performances.

The calibre of the some 70 programmed works ranged from the utterly raw (7, under-written, under-directed, but vigorously performed by Swinburne University Indigenous Arts Course students) to the half-cooked (Y-glam’s My Brother’s a Lesbian, a script with potential, some very good performances and a misleading title) to many that were consummately professional—eg Speak Percussion, Chris Brown’s Mr Phase, the excellent dance program at Horti Hall and many of the visual arts and new media works. This mix of standards is part of the festival’s character, as irritating as it can occasionally be, and is indicative of Next Wave as a testing ground, the festival as laboratory, working with the untried, the emerging and with communities venturing into the arts. Most of the works turn out well, for example, for example, Glowshow. The huge, internally lit inflatables spelling out Shipwrecked and Humanity, beside and across the Yarra, made for an impressively contemplative work from the Visionary Images team working with disadvantaged young people and artists. Risks are taken, the rewards are many.

This Next Wave was free, a significant gesture if you think about how expensive the arts are today, let alone the financial demands of forking out for numerous tickets for a festival. Bookings were largely taken online and a percentage of seats for performances kept available for walk-ups. It wasn’t long before the word was out and shows were packed, most notably the dance program and PrimeTime (a mix of serious and kitsch entertainments at North Melbourne Town Hall) but also the one night stand by Speak Percussion in a new music program. Next Wave staff and volunteers acquitted themselves admirably in handling the crowds.

There’s little to criticise about the 2002 Next Wave, but it does need to take a very serious look at is its opening ceremony. There was nothing about it that reflected its demographic or the works to follow over the next 10 days. Okay, there were Colony’s angels and the matching soundtrack with its young participants, but the speeches beforehand, delivered to a largely older audience, were dry and inherently patronising (how many times were the audience told to get out there and enjoy), directed at youth, for youth, but not of youth, but certainly of sponsors. In the same way festival also crucially lacks a physical centre, somewhere artists, media members and audiences can gather at any hour so that the works seen can be talked through, contacts made and future collaborations made possible.

RealTime was part of the 2002 Next Wave program. Editor Keith Gallasch worked from the Express Media (publisher of Voiceworks) office with a team of 9 writers (6 from Melbourne, 3 from Sydney) in their mid 20s to produce daily responses to festival works online and in limited print editions at festival venues. What follows are 45 responses to the festival from the RealTime-NextWave writing team (Ghita Loebenstein, Katy Stevens, Vanessa Rowell, Leanne Hall, Jaye Early, Clara Tran, Even Vincent and myself) and other contributors (Kate Munro, James Kane).

RealTime-NextWave is part of the 2002 Next Wave Festival.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 4

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

For better or worse, meat pies, football and throwing the odd shrimp on the barbie have become synonymous with all things ‘Aussie’. However, in a cultural melting pot as deliciously varied as ours, the search for a collective identity is neither useful nor relevant unless it begins with difference. The Viet Boys from Down Under is a play which explores the alienation and frustration that comes with not fitting into the fair-dinkum-jolly-swagman stereotype, or being wholly comfortable with one’s Asian heritage. It asks the perennial question: What does it mean to be Australian?

Having never been conflicted because I am part of two worlds—and not knowing many Vietnamese-Australians who are confused over issues of identity—I found The Viet Boys’ heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes in its search for answers somewhat uninspiring and cliched. Rather than challenge archaic notions of what it means to belong to eastern and western cultures, the play inadvertently perpetuates the very same attitudes it so obviously has problems with. Bong’s initial reluctance to become romantically involved with Brad because he is a ‘half-caste’ and not suitable for dating Vietnamese girls is truly cringe-worthy. Renditions of the theme song to Burke’s Backyard and the Vietnamese nursery rhyme Kia Con Buom Vang (The Yellow Butterfly), no doubt serve as easily recognisable pop culture signposts to a racially diverse audience and good for a chuckle, but fail to offer any meaningful discourse.

What saves this Vietnamese Youth Media project from becoming yet another tale of identity crisis turned up to ten is its strong and clever use of humour. Whether perversely ticklish and black, such as when Smithy hires a prostitute to act as his surrogate mother, or light and daggy, as in the case of a karaoke performance of Jason and Kylie’s forgettable classic 'Especially For You', there’s sure to be comic relief around the corner. The play mitigates the serious side of self-futility and depression with its ability to make us laugh, and in the process, manages to capture feelings that are both intensely subjective and universal. Before The Viet Boys, I never imagined that an Elvis Presley impersonator singing 'Are You Lonesome Tonight?' had the power to simultaneously hit me in the guts and rub my funny bone with equal force.

With a budding romance, a story of both broken and realised dreams, martial arts scenes and corny karaoke thrown in for good measure, The Viet Boys is nothing if not a colourful array of musical and multimedia delights. Pre-recorded video images are used as an extra narrational device in the telling of the characters’ individual stories, often times running concurrently with the live performances. Ray Rudd gives a solid performance as the aspiring kung-fu film star, while Hai Ha La shows she is comfortable alternating between her 3 contrasting roles.

Go see The Viet Boys for its entertainment value. Although it doesn’t push any boundaries or delve into unchartered cultural territory, the play does offer a perspective on what it’s like for some Vietnamese youth living in Australia. You might not come away feeling any more enlightened, but you will be uplifted. That’s a promise.

The Viet Boys from Down Under, co-writer/director Huu Tran, co-writers/performers Dominic Hong Duc Golding, Rad Rudd, performers Khanh Nguyen, Hai Ha La, Christie Walton; Vietnamese Youth Media, Footscray Community Arts Centre & La Mama; La Mama Theatre, Carlton, Melbourne; 2002 Next Wave; May 15-26.

RealTime-NextWave is part of the 2002 Next Wave Festival.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 4

© Clara Tran; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Christian Thompson, Show Me the Way to Go Hom

If Colony, with its angels winging spectacularly of the Victorian Arts Centre Spire was just too ethereal or kitschy an experience for you, Christian Thompson’s Show Me the Way to Go Home, in the George Adams Gallery beneath the spire, provided a neccesary earth. Slide projections on 4 large screens right-angled against each other, fill the space. The slow pulse and dissolves of the screenings create a semi-cinematic space of recollection. Christian Bumbarra Thompson (Bidjara/Pitjara people, Carnarvon Gorge, south-west Queensland), resident in Melbourne since 1999, has re-enacted elements of his childhood on the land he grew up on and photographed them as a series of movements. A woman looks in a mirror as she applies makeup, lost in her reflection. We see her from various, intimate angles. A young Indigenous man in a military outfit stands to attention. He salutes. He looks into the distance. A woman, she appears to be white and is dressed as a nurse, watches Indigenous children at play. A large, handsome woman, brightly dressed and with flowers in her hair seems to sing in a darkened space, a club perhaps. These performances are inspired by photographs from the Thompson family album: “I guess you could say I am trying to recreate and savour the very elements of my past that have conditioned me to be the type of aboriginal person I am…I am a long way from my blaks Palace, from my country, but every day I try to be there spiritually…” (Catalogue dialogue.) According to a wall plaque, the soldier is based on Thompson’s father and the nurse his mother. Show Me the Way to Go Home is a lyrical work, quietly, thoughtfully engaging and memorable.

–

Show Me the Way to Go Home, artist Christian Thompson, curator Kate Rhodes, George Adams Gallery, Victorian Arts Centre, Melbourne, Next Wave, May 18-July 14

RealTime-NextWave is part of the 2002 Next Wave Festival.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 4

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

By combing the working processes of 2 traditionally opposed mediums, documentary filmmaking and visual art, Simon Price and Simon Terrill have set out to challenge perceived divisions. Their exhibition thematic becomes: Where does the seamless conduit of a freeway and its implied utopia lead us? Their answer? To a world where space is a transition zone and identities become less grounded and more anxious. By adopting the distinctive perception of hitch-hikers, both artists embarked on a deliberately lateral journey from Melbourne to Darwin and along the way recorded their random experiences. The exhibition reflects a space where the 3 zones of the highway (human, machine and landscape) meld together to create unique relationships and multi-layered realities. The result is an exhibition divided into 3 rooms comprising sound, sculptural kinetics, the still image, a diorama—and the formation of an anxious reality.

Entering the first room you are greeted by a speeded up monotone voice describing casual encounters of the everyday…a cigarette…a dog…a car. A hurried succession of flashing vertical lights project onto a cube-shaped construction made from metal. Thin opaque material hangs in the cube receiving a succession of vertical lights. These seem to correspond to the pace of the voice. The work creates a chaotic and disjoined reality, by describing an uncertain narrative that weaves its way through a unknown landscape.

The second room consists of a video recording of 2 men projected onto a large wall space. The film is muted and plays in slow motion—its manipulation creates an eerie almost sinister atmosphere. Afigure sits in the foreground while another engages in a game of table tennis. Both are oblivious to the gaze of the camera recording, in detail, their every move. They appear to be detained, locked in a serious bout of navel gazing. The identities of the men are unknown and the viewer is left to form their own narrative of their reality. (The film is in fact of two British backpackers passing time whilst attempting to find relief from the intense Darwin heat.)

The third room consists of film, a diorama, and sculpture. One screen captures the ambience of the silent roadside vigil of hitch-hikers eager to be picked up—an exploration of the roadside universe takes place. What we see is a roadhouse late at night as a truck passes without any consequence, its headlights illuminating a kangaroo represented in large sculptural form. This image is then sharply juxtaposed with one on another screen of what appear to bespectacular blue glowing intersecting lights from an LSD trip. The camera slowly tracks to hundreds of frantic insects drawn to a roadside light. Situated inconspicuously, towards the back of the room, is a miniature 3D diorama replicating an aerial-map view of a fibre-optical landscape dissected by a piece of road implicitly symbolic of the exhibition’s journey theme.

The exhibition succeeds in creating a particular, anxious reality where the concept of space—both the literal floor space and gestalt of the hitch-hikers’ point of view—becomes a transition zone left open to audience interpretation. Or, as Simon Price explains, “ A zone where people can build their own narrative.”

Human/Machine/Landscape, artists Simon Price & Simon Terrill, fortyfivedownstairs, Melbourne, Next Wave; May 17-26.

RealTime-NextWave is part of the 2002 Next Wave Festival

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 4

© Jaye Early; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Journey to Con-fusion #3: Not Yet It's Difficult and Gekidan Kataisha

Through the smoky haze in a twilight space there are people with no names and eyes that don’t seem to see. This place lies beneath words and thoughts, and if you are looking for sense there is none to be made. Ghosts, the raw, concentrated people before you are walking the edge of a precipice, waiting to be startled, recoiling at the slightest movement.

When they sit in chairs they fall backwards, looking at an absent sun, the backs of the chairs arching their spines, conjuring grasshoppers rubbing between skin and ribs. They flap, they gasp, necks straining, fish caught too far from the cooling sea. They sit bolt upright, breath drawn loudly to the back of the throat, flight in their bodies and eyes.

What are you so afraid of? Where do you think you’re going?

A clamour of music issues a loud invitation to dance. A man romances his battered suitcase across the room, fixing it with a besotted gaze before stopping to laugh at its Pandora depths. Around him a mad circus of movement revolves without pattern. Two men, with stature and dignity, hold each other firmly and waltz majestically around the room. A girl in a full-skirted dress is hounded by her double pecking fretfully at her hem; still others dance in a whirligig of hysteria. Everything in this place is reduced to neurosis, carbon-copied so many times it becomes a tic, a spiralling cocoon that you can’t break out of.

She embraces him, folds him with tender arms into the smooth hollow of her neck. And then she grabs him by the hand and flings him headlong into the wall, where he is pinned loudly before sliding limply and heavily to the floor. She lifts him gently, letting him melt childishly against her chest, and then throws him brutally at the wall, over and over in a merry-go-round of love and hate. But soon she infects even herself with this madness and they both hurtle together violently, animals in a cage. They could be trying to escape unseen terrors, or they could be trying to enter a Paradise just visible through the glass, but maybe they don’t know what they are doing at all.

If I bind your face in cloth, making you deaf and blind and dumb, and remove your clothes to shame you, are you still human? Or will you roll across the floor, willy-nilly, handcuffs clenched behind your back, scaring those don’t want to see you too close? Will you prance angrily in your high-heeled shoes, flicking your bangled arm out in frustration so many times it becomes nothing more than a compulsion?

There is a man with a granite face, wearing a silky grey dress with heaviness and dignity. He carries a metal bar in his powerful hands, rolls it across the floor with the soles of his feet. He could be by your side in a split-second. Behind you, someone is walking slowly past your chair, trailing audibly against the walls and softly brushing your clothes.

People tilt and swerve, running to clap up against each other in a cymbal crash of skin, grappling like wrestlers, colliding like old lovers. It’s not possible to know who is a protector and who is a predator. You can smell their sour sweat as it trickles fear.

Peel yourself gladly from this unrestful dream and relax. Unfurl your fingers, set your heart ticking metronomically. Rise to the surface and feel the breath held in the small of your back, tucked under your ribs and around your stomach. Breathe again.

Journey to Confusion #3, Not Yet It’s Difficult & Gekidan Kaitaisha, Dancehouse, Melbourne, Next Wave, May 18-22.

RealTime-NextWave is part of the 2002 Next Wave Festival

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 4

© Leanne Hall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Journey to Con-fusion #3: Not Yet It's Difficult and Gekidan Kataisha

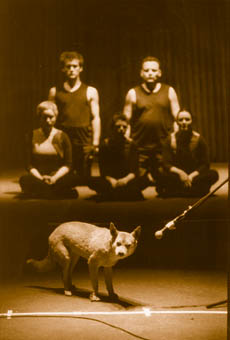

Intercultural theatre projects have explored diverse artistic and social practices since Peter Brook and Suzuki Tadashi in the 6os and 70s. Journey to Confusion #3 is a performance research project from Melbourne company Not Yet It’s Difficult and Tokyo’s Gekidan Kaitaisha. The cross cultural partnership began in 1999 with a season of Confusion #1 In Melbourne and subsequent work in Japan.

In Confusion #3 the companies create a unique time-in-space through intense physicality, prepared movement and various tensions. Neither company has banished their cultural viewpoint in the search to find cohesion. Instead of attempting to reconcile their contrasting body vocabularies they are, rather, observed. The juxtaposing of the performers’ histories and techniques strangely clarifies archetypes and symbols. Many of the solo moments within the piece characterise situations more associated with one culture than the other.

Through stillness, movement and voice the performers generate a palette of textures and tones. It is not necessary to grasp a single unifying thread, but rather embrace the confusion of humanity beside humanity. Confusion #3 begins as the silhouettes of 10 figures enter the space in a haze of mist. Their features are undefined, their identities ambiguous; they are also gagged. The long and slow silence forces me to observe the speech of the body and I become aware of a quivering energy present despite the calm. In Japanese theatre such as Butoh and Noh, performers move as result of the inner landscapes they create. It is this that I can feel penetrating the space between the performers and audience.

Confusion #3 is personal and political, subjective and global. There is very little by way of design, and only a few minor props—the power bestowed in the technique of the performing body activates the transformation of the space. Whilst the structure appears to be fixed, a lot of the actions, rhythm and pathways are dependent on improvisation. About a third of the way through the performance a number of the motifs have been articulated, including repetition, transformation and a suggestion of phantom pain. These return later in the performance.

By the end of the work there is an undeniable sense that the performers are trapped; hostages to the space, their bodies and their cultures. In an early sequence that builds to the point of audience discomfort, a performer flings himself against a wall. Another performer helps him up and then flings him straight back against the wall. This duet is repeated over and over with the whole company. It then implodes further as all the performers slap themselves against the stark white wall. I shudder as I watch the room fill with bodies trapped in repetitious assault on each other and themselves. Over this plays a country and western ballad with the lyric “In a world of my own” which doesn’t quite drown out the sound of flesh hitting walls.

With smeared lipstick, naked flesh, handcuffs, 10 dollar bills and dirt, agonised screams and spoken abstractions, Confusion #3 has all the elements of avant-garde theatre. It is rare that a performance has the intensity to leave you at the end of the show with quaking knees. It is not an easy to watch. This is no tame exploration of the body in performance and that is a good thing.

Journey to Confusion #3, Not Yet It’s Difficult & Gekidan Kaitaisha, Dancehouse, Melbourne, Next Wave, May 18-22.

RealTime-NextWave is part of the 2002 Next Wave Festival

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 4-5

© Vanessa Rowell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In a festival high point, a young, curious audience packed the VCA Dance Studio 1, to hear Speak Percussion, 4 about-to-graduate VCA musicians with an impressive program, Argot: A Transient Vernacular. It boldly combined the percussive purity of Takemitu’s Raintree (serene perspectives on rain drops) and Robert Lloyd’s Boobam Music (a fast, loose-limbed, virtuosic rendition by 2 percussionists on 8 bongos) with new works layered with samples and dance and classical music from young Australian composers Brett Anthony Jones (Pauah Fayliah Bacchanaliah, alternating riff-driven passages and demanding unravellings) and Peter Head (You are here: Rubik’s Cube, an intriguing use of staccato CD cut-ups against minimalist rows ). Alan Lee’s Artikule, an etude, the third Australian premiere, is built from mouth sounds made into microphones—clicks, trills, pops, various breathings. A corresponding dance trio explored the pleasures of the tea-cup. This was a generous concert, the works augmented by dance (a little old-fashioned) and thematic projections (strange morphings of a tea cup into a foetal scan into a cell). Finally the musicians and composer-electronic artist Harry Arvanitis (all dressed like laboratory scientists in white plastic coveralls) created an epic drum’n’bass & ambient improvisation. We could have danced to it, but locked in our seats we had to wait a long time before the work (a little too heavily earthed by 2 drum kits) took off…and it did. It’s interesting to note in the Jones, Head and impro works an inclination to orchestral volume and intensity (thanks to the layering in of recorded sound)…a new romanticism? Speak Percussion are surely makers of the next wave. As they write in their program notes: “Argot is a hybrid arts event…where elements of the concert hall will evolve into those of the Rave.”