Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

The Tissue Culture & Art Project

www.tca.uwa.edu.au

Following the Pig Wings Project, where we grew pig’s bone marrow stem cells in the shape of the 3 evolutionary solutions to flight in vertebrates (Bat, Bird and Pterosaurs), we would now like to animate them using muscle cells (from IGF-I transgenic mice as well as cardiac cells) as actuators. Besides the difficulties to do with aligning the cultured skeletal muscle cells and their use as actuators, we also have to modify the wing structures in order for the tissue to be able to animate the whole construct. The use of IGF-I mouse tissue, which is more efficient in its use of energy in comparison with its mass, will make this endeavour more achievable.

Animated Pig Wings will look ‘more alive’ and further challenge the audience perceptions of our Semi-Living Sculpture as evocative objects that blur the boundaries between what is alive/non-living, object/subject, and body/constructed environment.

The other research we are conducting is the development of a bioreactor for artistic purposes. Developing an interactive bioreactor (the ‘vessel’ which imitates body conditions for the cells to grow and be sustained alive) will enable us to present our Semi-Living Sculptures in non-specialised environments (such as art galleries) with no need for constructing a whole tissue culture lab. An interactive bioreactor will enable the audience to directly interfere with the environment in which the tissue grows and take an active part in caring for the Semi-Living Sculpture.

The research will be mostly conducted in SymbioticA—the Art and Science Collaborative Research Laboratory, School of Anatomy and Human Biology, University of Western Australia. Anyone interested in this research can contact Oron at oron@symbiotica.uwa.edu.au.

Oron Catts & Ionat Zurr

Machine Corporation

www.machinecorporation.com [link expired]

Machine Corporation is a satire about corporate websites and networked utopias. It uses Flash and action scripting to create an interactive user experience incorporating elements of character-driven narrative.

Machine Corporation offers a series of software products for free trial. In return users submit some very harmless information about themselves that Machine Corporation will respect and not on-sell to porn sites or marketing companies.

The authors hope to explore the possibilities of virtual space as the parameters for online narrative. The complexities of incorporating interactivity into this environment are handled by structuring and designing the narrative based on the familiar concept of interactive forms that are commonly encountered on the web.

In the tradition of culture jamming, part of the satire is corporate anonymity; therefore we refer to ourselves as faceless man 1 and faceless man 2 rather than identifying ourselves.

–

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 23

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In his book Blue Fire, experimental psychologist James Hillman finds a spiritual meaning for graffiti in the modern metropolis. Random, indecipherable scatterings of information are inscriptions of soul: markers of resistance.

Marks in public places put a face on an impersonal wall or oversized statue…the human hand wants to leave its touch, even if by obscene smears and ugly scrawls, bringing culture to the walls and stone…

Hillman, A Blue Fire, Routledge, London, 1994

The cyberspace of the future, being hardwired now by marketing and PR professionals, is a landscape deserving of such effacement. Yesteryear’s digital revolution catchcry, “information wants to be free”, has been seemingly subsumed into corporate monoculture. The push is on to wash the internet clean of civic and social possibility. Copyright, 300 years old in 2009, is again the tool of monopoly control for the traditional owners of cultural intellectual property: the publishing, entertainment, and distribution industries.

The 1998 US Digital Millennium Copyright Act attempted to regress the public enjoyment of digital materials to pre-web levels. The entertainment industry, aware that video files can be pirated like MP3 music files over the internet, successfully lobbied the US government to provide the legal framework to allow complete control over the technology of digital audiovisual media. The DMCA forbids the distribution of any technology that can bypass copy protection schemes. This is akin to telling consumers if you own a CD player and cassette recorder, you’re guilty of music piracy.

Jon Lech Johansen, a 16-year-old Norwegian boy was charged for breaking intellectual property laws by publishing on his website DeCSS code for decrypting DVD technology. Johansen and his friends were not intending to infringe copyright, they claimed only to share the code to create a Linux platform DVD player. Emmanuel Goldstein, publisher of 2600 Hacker Quarterly, was charged under the DMCA for the same offence, and was accused by entertainment industry lawyers of “endangering the future of American movies.”

Regardless of the aggression of the new US laws, a quick scan of what’s available on the gnutella file sharing network makes it clear copyright (as we know it) isn’t going to live long beyond its 300th birthday. Hollywood blockbuster films like American Beauty are waiting to be downloaded in a cracked, DVD-compatible format.

As the saying goes: “every new law creates an underclass.” The DMCA has generated nadirs of flourishing subterranean hacker cults and legally evasive file sharing communities. These groups, like graffiti artists in the city, deface with their program codes the monuments of copyright control: with new hacks and cracks that are conscious, romantic, acts of resistance.

Free information advocates believe that copyright protects the economic interests of publishers and distributors, above the artists and communities who would benefit from a liberalised information marketplace. Nobody is saying artists should not be paid. What is argued is that peer-to-peer file sharing networks over the internet herald a step towards a new cultural economy, one that will greatly benefit artists and audiences in the long term.

Music file sharing, an example of what may happen with future film distribution, demonstrates new possibilities for musicians: a direct relationship between audiences, a form of ‘radio’ not mediated by the recording industry, global in reach, and communal in practice. No royalties are given to artists through free downloads, but the ability to distribute music outside the record company monopoly is itself revelatory. MP3 files can be sent around the world, at virtually no cost, with next-to-no effort, and without respect for jurisdictional boundaries.

Last year, on the Kazaa network, I found a bootleg of an obscure song that was not available for sale. Because of the rarity of the find, I investigated my host’s shared music library further (a feature most P2P programs share), and selected titles from the musicians @@@@. I’d luckily found a likeminded person randomly through the digital hook of an obscure piece of music: the file sharing community acted as the educational resource, leading to an exchange of ideas and music that did not require the music industry to play its usual role as controlling taste-maker. With little or no profile on local radio for @@@@, it was copyright infringement that led to my money reaching the artists. I purchased their album and paid another $50 to see them on their Sydney tour.

Clearly, the argument that free P2P file sharing does nothing but exploit artists is more complex than the entertainment industries would have us believe. The music industry itself was never able to conclusively prove that Napster or other MP3 file sharing networks did anything but increase record sales.

As bandwidth increases and compression programs improve, digital media will inevitably become a primary distribution mode for film. What online digital distribution represents for Australian short film, already starved of exhibition possibilities, is the opportunity of reaching online film community networks globally. The Australian and international festival circuit for short film is limited: only SBS’s Eat Carpet broadcasts short films on television nationally. The potential reach of the file sharing networks, and their ability to create a community of ideas about film, can only increase the profile of Australian short films locally and internationally.

Sites like Atom Films (http://www.atom.com/ [updated link]) have successfully exhibited short film for several years now, focussing on one-liner comedies and simple, net-friendly animations, boasting 16 million unique visitors each month (see “Small screen desire”, p19). While it’s a good example of a thriving commercial model of short film distribution, it lacks an awareness of film beyond broadly consumable entertainment.

Thankfully, it might be the hacking community that finds a way to make the distribution of film on the internet simpler, faster, and determined only by audience interest. While a post-DMCA environment will affect the availability of digital media sharing technology, the law can only ever be a minor variable in the future dissemination of audiovisual intellectual property.

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 24

© David Varga; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Perth International Arts Festival Director Sean Doran showed an alarming prescience when establishing elemental themes for his 4 festivals. The 2000 festival was themed ‘water’ and sure enough, it began with an unseasonable deluge that drowned out the Philip Glass opening night concert. The 2001 ‘earth’ Festival was-given the financial excesses of the previous year-much more down to earth! This year’s ‘air’ festival, despite a couple of nervous moments at Sticky—the opening performance spectacular in the far northern suburb of Joondalup—appeared to have escaped the literal elemental connection. Sticky relied on thousands of feet of sticky tape for its effects, so the mildest zephyr could be perilous. But this surprisingly beautiful spectacle moved without incident to its ambient and pyrotechnic conclusion.

360° in the shade

At the festival’s closing event, a freezing southerly buster made the experience of Amoros et Augustin’s 360° in the shade acutely unnerving. The show involved the installation of a huge projection screen, stage and rig on Cottesloe Beach (on possibly the windiest coast on the planet). The appalling weather made it hard to concentrate on anything but the risk to performers’ life and limb. This was a pity because there were fascinating moments in this performance which evoked a history through familiar and resonant images, from the cave paintings at Lascaux to the shower scene from Psycho; from sand paintings in the Navajo Desert to the photographic experiments of Thomas Muybridge and the paintings of Aboriginal desert people. To create these images the performers used a mix of live video feed, shadow theatre, action and sand paintings, mirror writing, live vocals and percussive beats: both astounding and ingenious.

While there were no instruments, the stage was constructed like a huge percussive instrument using a network of microphones, cells and sound sensors, distributed over the performers’ bodies, the screens, the floor and stage structure. The tightly scored composition was not to my taste and some of the images verged on the generic and overly romantic-often the case when European artists address Indigenous cultural traditions-but nevertheless it was a fascinating and committed performance by an extraordinary group of artists. My anxiety regarding the appalling weather was borne out on the second, equally windy night, when one of the performers slashed his hand and was dashed to hospital. The theme for the 2003 Festival is fire-I might just have to leave town!

Marnem Marnem Dililb Benuwarrenji, Fire, Fire, burning bright

Fire, Fire, burning bright

Some performances are highly polished, seamless theatrical events, constructed and informed by modern and postmodern tenets of capital ‘A’ art and the European and North American cultural tradition. Other work, while cognisant of those traditions, is recast in the vernacular of local influences and histories. Other performances are a gift-an opportunity to see, hear and witness the very different performance traditions-no matter how uncomfortable. This was certainly the case with the extraordinarily confronting Fire, Fire, burning bright (Marnem Marnem Dililb Benuwarrenji), written by Andrish St Clare and based on the traditional dances and songs of the Gija people and a true story told by Paddy Bedford and the late Timmy Tims.

Presented outdoors on a sandy stage at Belvoir Quarry, surrounded by trees, Fire, Fire tells the previously “hidden” story of the massacre of a group of Gija and Worla people murdered by white station workers and owners for killing and eating a bullock during a break from station work. The performance is a contemporary rendition of a traditional east Kimberley joonba (or corroboree) created for the stage. As such, this joonba, named and endorsed as a new style by the traditional owners, adheres closely to oral histories and incorporates the traditional songs and dance of the original sequence. St Clair explains, “the traditional performative culture of Australian Indigenous people is not primarily narrative. All the people in the community from Elders down to children usually already know the story, or at least the outside version which is open to all members of the community, so the need for narrative is absent, or coded very loosely…” (program notes). This means that the original joonba does not tell the story directly, but instead concentrates on what in western terms would seem to be peripheral details-in this case-the journey of the murdered men’s spirits.

From the shocking opening image of a corpse crackling on a fire, to the appearance of Gija people in ‘white face’ performing the roles of station owners, workers and police, this extended performance presents us with many extremely confronting images from our shared history. Despite considering myself reasonably informed about the atrocities committed in the name of colonisation, I was surprised at how disturbing it was to witness the Gija people telling this story. It was profoundly shocking to watch the whited up Gija men depicting the abusive language (“ya black cunt”, “bloody nigger” etc) and murderous actions of their white bosses.

The “hidden story” occurs earlier in the production. According to Peggy Patrick, (Company and Creative Director, singer, performer and Law) it was hidden because “people who were still working on stations were scared that if white people saw this joonba or realised what it was about they might all be shot themselves.” The latter part of the story presents the original joonba, the spirits’ journey, and contains audiovisual projections of country and traditional songs and dances with voiceover to explain the journey. Ironically, it was this part of the production, furthest from the concept of western theatre, that many of the non-Aboriginal audience were most uncomfortable with, finding it extraneous to the narrative drive.

The act of colonisation was ugly and brutal. Healing can only occur through a significant striving and an ability to bear witness to the violence enacted against Indigenous people in Australia. The listening can be painful and the truth uncomfortable. As Patrick says, “We want people to look at the show, to enjoy the song and dance and to learn what happened to our people in the past. Before, Aboriginal people were really frightened of white people. Now we hope we can all be friends together”.

One Day in ‘67

Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre’s production, One Day in ‘67, written by Mitch Torres, tells yet another story about Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal history, this time focussing on a tough but close knit relationship between a mother (Ningali Lawford) and her two daughters (Irma Woods and Ali Torres). One Day in ‘67 refers of course to the historic referendum in which white Australians voted overwhelmingly for Aborigines to be included in the national census, effectively giving them-somewhat belatedly-citizenship rights. The referendum forms a schematic backdrop for what is primarily a domestic drama-a heightened piece of kitchen sink naturalism. I thoroughly enjoyed this lucid and often funny production, which included outstanding performances by Lawford and Woods in particular, and Humphrey Bowers making the most of his role as the radio man playing the ABC’s signature tune on a ukulele.

The dramatic tension revolves around the relationship between the mother, Ruby, and her two daughters, one of whom is heavily pregnant. The first half ambles along in what feels like real time. The second half erupts into an enormous brawl between the two sisters. One sister has grown up with her mother in the mission, while the other was ‘stolen’ because of her lighter skin and given the ‘advantages’ of a white upbringing in the city. Torres adeptly negotiates the relationship between the 3 women to explore not only generational but cultural differences. Ivy (Woods) is determined to take up the cause for civil rights and shames her mission bred sister, Maudie (Ali Torres). Maudie sees her sisters’ adoption of a more confrontational mode as an implicit rejection and diminution of her own more traditional upbringing. There are some unbearably poignant moments in this play, offset by the sheer energy and cheeky humour of Lawford and Woods.

Shadows

PICA hosted three solo performances on behalf of the Festival, including William Yang’s memorable and moving, Shadows. I became quite accustomed to arriving at work and finding yet another PICA staff member in tears following the show. Whilst much of it was extremely poignant, there were also moments of hilarity, from the opening images of garden parties at Government House for the 1980 and ‘82 Adelaide Festival of the Arts, to an ostensibly artless statement on censorship, delivered deadpan, while a large flaccid penis is projected on screen. Yang’s work always appear artless, when of course, it’s highly constructed, drawing many apparently disparate threads into a tightly woven whole that comments acutely on our humanity, or lack thereof.

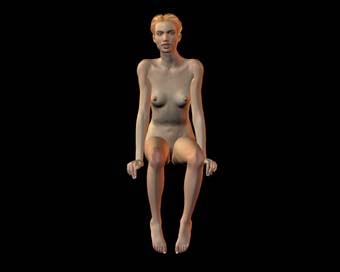

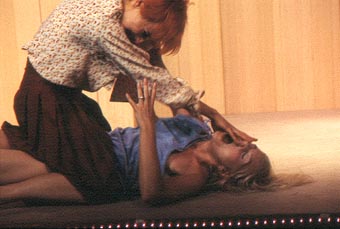

Plastic Woman

Plastic Woman

A particularly interesting performance Plastic Woman, presented by Thai Community Theatre Group, Maya, told in an endearing mix of Thai and English (and surtitles) the story of a “plastic woman” constructed by scientists to be the perfect sex machine. With the bare minimum of lights and props, the only set was a table to which was clamped a cheap and nasty plastic mannequin’s head wearing a truly dreadful wig. The script, originally written as a solo performance for a woman, is performed by a man, putting a very different spin on the performance. Thai TV star Asadawut Luangsuntorn’s compelling physical and occasionally sexually explicit performance conveyed the hypocrisy of a society that projects its own sexual fears and pornographic fantasies onto the figure of the desired woman. At the very end of the show, when the appalling statistics about the sex tourism industry (particularly with minors) start to scroll down the screen, we understand that this Brechtian style parable has an Australian audience well in its sights. The majority of the 5.4 million sex tourists who arrive in Thailand each year are Australian and German men. Something else to be proud of.

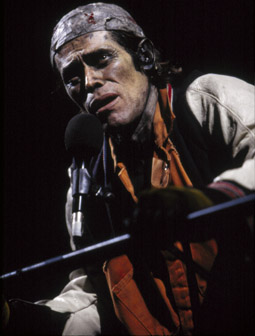

Failing Kansas

Not everything in this festival was to do with challenging content. At the high modernist end of the spectrum were two very different works—Mikel Rouse’s solo opera, Failing Kansas and the performance installation for fifteen voices, An Alphabet, by John Cage. The former was an hour long “tragic” opera very loosely based on Truman Capote’s renowned In Cold Blood, which explores the events surrounding the murder of the Clutter family in Holcombe, Kansas. The connection escaped me completely. I do not mind opacity, but having established the formal parameters of the work ten minutes would have sufficed. As it was a late night show, I took the opportunity to catch up on a bit of sleep.

An Alphabet

However, I loved An Alphabet, adapted from John Cage’s radio play of 1982. For me, Cage is a seminal 20th century figure and his ideas have informed much of my thinking about art and performance. Presented as an almost sculptural installation, the play assembles the luminaries of the avant-garde modernist tradition: James Joyce, Marcel Duchamp, Rose Sélavy, Henry David Thoreau and Erik Satie as well as Robert Rauschenberg, Buckminster Fuller, Merce Cunningham and a 9 year old Mao Tse Tung. Their conversation comprised quotations from theories, lectures, manifestos, novels, freely adapted historical material and lines Cage simply made up. The dialogue is both live and pre-recorded and juxtaposed with fragments of musical and pedestrian sound. Cunningham gives a brilliantly understated and charming performance, playing not himself but Erik Satie. Mikel Rouse is James Joyce, and an utterly virtuosic John Kelly is the narrator. The performance also included local “celebrities” such as State Gallery Director, Alan Dodge as Rauschenberg, Alistair Bryant, Director General of the Department of the Culture and the Arts as Buckminster Fuller, and Channel 7 newsreader, Peter Holland. Though adapted for the stage after Cage’s death, this performance truly inhabited the world of Cagean aesthetics. Set on a stair-step structure, the cast, with the exception of the narrator, remains relatively static. The performers shift only at precisely choreographed moments, striking intermittent poses in a slowly evolving tableau.

–

Sticky, Improbable Theatre, Joondalup, Feb 2, 3; 360° in the Shade, Amoros et Augustin, writer Marie Jones, director Ian McElhinney, Indiana Tea House, Cottesloe Beach, Feb 15-17; Fire, Fire Burning Bright, The Quarry Amphitheatre, Feb 6-10; One Day in 67, Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre, director David Milroy, Subiaco Theatre Centre, Jan 28-Feb 16; Plastic Woman, Maya-The Arts and Cultural Institute for Development, director Santi Chitrachinda, PICA, Feb 5-8; An Alphabet, director Laura Kuhn, Playhouse Theatre, Feb 14-16; Perth International Arts Festival.

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 24

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

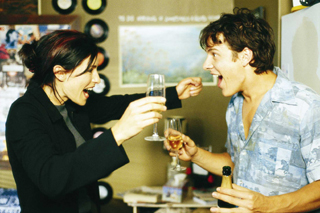

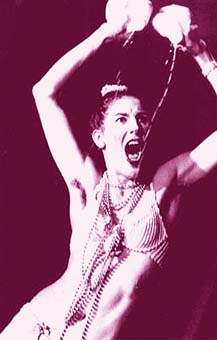

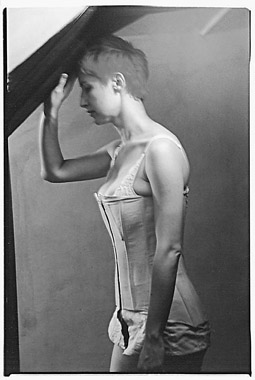

Moira Finucane

Like the feast day after which it is named, the Midsumma festival is an unruly, hedonistic celebration, including events as different as The Festival Jack-off and the launch of Andy Quan’s Calendar Boy. Cabaret, monologue and deferred biography provided the 3 main trends that the arts events engaged with. Cabaret has a long association with queer aesthetics, the self-conscious performance of gender, identity and sexual allure offering a vision of society beyond the straight world. One must nevertheless question the inclusion within the festival of relatively ‘straight’ cabaret like Hell in a Handbag or the New Age lecture Imagining the Pleiades (unlike the pataphysical, stream-of-consciousness cabaret of the same month, Dilapidated Diva). Even Warhol’s dry, ironic persona was more dangerously camp than some Midsumma works.

Though ostensively a para-literary event, the Word is Out program had a cabaret ambience too. Writers recited texts in some cases written for performance in a relaxed manner, amongst the barely theatrical surrounds of a former Trades Hall meeting room. Love is the Cause for example included Richard Watts, schooled in the spoken-word scene which thrives amongst the back rooms of Melbourne’s pubs and clubs (Watts helped establish the nightclub Queer and Alternative). He has an endearingly rough-and-ready, almost improvised style, employing relatively simple language as he read from dog-eared pages. Kylie Brickhill echoed Watts in her rough comic approach, slamming on her guitar in an unaffected manner as she performed exerpts from her show Pick Me. She was delightfully naff, sending up her past as a young, newly-out lesbian who joined a band to “pull chicks.” Both seemed relatively weak however beside the 2 published authors on the program, a less than ideal juxtaposition of forms and styles.

Merrille Moss recited a tight—albeit slight—published monologue which at once mocked—while covertly celebrating—the indulgent self-pity of a recently dumped young lesbian. Andy Quan’s selections from Calendar Boy on the contrary were rich, expressive passages wrought from the simplest of elements. He employed a relatively unadorned, observational style which kept the emotional content at a certain remove. This proved intensely affective though in his study of the dangers of love, following a character who only barely avoided an abusive relationship. There but for the grace of God go I, seemed to be the message.

This perplexingly moving objectification of the personal was also exhibited in William Yang’s writing. For Yang however this occurs on a scopic level as well. The projected photographs that went with his words possessed an intimacy paradoxically accompanied by a sense of disinterested remove. As Yang himself explained when discussing images of his lovers, or how his camera enabled him to mingle with the lesbian community, the photographic lens offered him a way to get close to these figures while nevertheless remaining apart. Although Yang’s work has often been described as autobiographical, he provides too little information about himself for this to really be true. Friends of Dorothy is only autobiographical inasmuch as Yang’s persona can be described as that of the watcher—engaged yet detached, loving yet coolly documentary.

The most surprising aspect of Friends of Dorothy was how uncertain a speaker Yang is. Although he has been touring slides-and-text for years, he still tends to falter, before quickly picking himself up again. Here audiences once more found themselves in the intriguing, shifting sands of informal cabaret performance.

Melbourne is indeed home to a thriving cabaret scene, spreading from the queer clubs, to swish cafes where slick groups like Combo Fiasco perform, right through to La Mama. Theatre-maker John Bolton has provided a common departure point for the more theatrical manifestations of this form, drawing upon street performance, French clown and Jacques Le Coq. Hell in a Handbag (featuring Bolton-trained Merophie Carr) strongly exhibited the self-deprecating ‘theatre of naff’ style found amongst Bolton’s associates (Four on the Floor, Born in a Taxi, Kate Denborough). Handbag was not the best example of these approaches though. It compared poorly to coincident manifestations, like the more dreamy, melancholy, Calvino-esque ‘tales-of-a-city’ show Sailing on a Sea of Tears. It seems somewhat churlish however to criticise Handbag for its inconsistency given the free-form cabaret format widespread throughout Midsumma overall.

Although Moira Finucane and Jackie Smith produce highly charged, multifaceted works, their projects are characterised by a discipline elsewhere lacking in the festival. Finucane has been performing various characters she devised with director/dramaturg Jackie Smith for nearly 10 years in clubs. Nine were first brought together for The Saucy Cantina in 1999. More performance-art style figures like the Dairy Queen (spraying milk outwards and onto herself in an over-the-top, hyper-sexual game) have become infamous through guest appearances, yet Finucane’s rich, neo-Romantic, Gothic text work is less well known. Her dark, Edward Gorey/Mervyn Peake-style Expressionist melodrama Phantasmagoria (2000) failed to win the attention it deserved. Her Word is Out performances however demonstrated she and Smith have more stories and characters to offer. Their next project—Gothorama—is sure to be extraordinary.

The Smith/Finucane collaboration was the most threatening work within the festival. Sauce-Girl in Saucy Cantina was exemplary in this respect, a fiercely controlled yet minimally twitching woman staring into space as she squeezed a leaking sauce bottle. Her bizarre lust took the logic of gay and lesbian liberation to a frightening level. If all forms of sexual desire should be equally free, then Sauce-Girl represents desire for desire itself, a character who does not need another individual or even a particular fetishistic object. The work of Smith and Finucane is therefore more concerned with the exploration of emotion, desire and ritual behaviour, than with promoting particular sexual identities. Finucane’s characters are typically defined by a fragile beauty, a power and elegance bordering on fragmentation and death. Her Love is the Cause monologue painted a rich yet frigid picture of a deserted, frozen mansion where 2 siblings waited for “him”—presumably their father, but Finucane allowed no certainty here, only deeper mysteries—who bicker and protect each other in equal measure. Finucane delivered the tale with her characteristic tall, cracked, physical grace. It is indeed impossible to imagine Finucane’s works as purely written text, a trait that lifted her above her peers.

Her second Word is Out appearance featured her exuberant Latino-goddess: La Argentina. In Saucy Cantina, Finucane was ritually cleansed before transforming from Sauce-Girl into La Argentina, who described a food-market in which sexualised wares fell over themselves to proclaim her beauty. In Oceans Apart however La Argentina spouted a tale of ludicrous proportions, a rollicking, insane story of life with polar bears, kidnapping and gypsy-pirates. La Argentina is the only unambiguously life-affirming figure in the gallery of Smith and Finucane, a proud woman whose “firm arms” and “heaving bosom” metaphorically embrace the world.

The most suggestive aspect of the Word is Out program was the Auslan interpretation. Signers Lyn Gordon and Tanya Miller imparted a literally palpable sense of drama, offering their own distinctive inflections which undercut the writers’ authority, even as the latter read their texts. Gordon ‘spoke’ with a sense of shrugging melodrama; a rapid rim-shot approach of punctuated physical expression. Miller however had an easy nonchalance. Compared to Gordon, she almost slurred her physical speech. Her movements rolled out, tapering off into thoughtful poses.

These idiosyncratic physical dialects highlighted the tension at the heart of both the readings and authorship itself. One could actually see entire phrases collapsed into single, eloquent, nuanced gestures. Other relatively straightforward words engendered a flurry of physical activity, changing the emphasis of the text. Miller and Gordon dramatised how the meaning and expression of a text changes as it leaves the author. In Word is Out, the quicksands of physical cabaret sucked at the writers’ feet.

Midsumma: Hell in a Handbag, performers/devisors Shirley Billing, Merophie Carr, directors Vanessa Pigrum, Rebecca Hilton, Jan 22-Feb 2; The Saucy Cantina, director/co-creator Jackie Smith, performer/text/deviser Moira Finucane, performer Sandra Pascuzzi, Jan 22-27; 4Play, including Pick Me, performer/deviser Kylie Brickhill, Jan 15-19; Friends of Dorothy, performer/deviser/photography William Yang, Jan 31-Feb 2, Blackbox; Word is Out: curators Crusader Hillis, Rowland Thomson, Auslan interpreters Lyn Gordon, Tanya Miller, Trades Hall, Jan 26; Sailing on a Sea of Tears, performers/devisors Fiona Roake, Jesse Griffin, Terra Paradiso, Jan 29-Feb 15; The Dilapidated Diva + her Tight Three Piece Outfit, performer/deviser Emma Bathgate, director Barry Laing, Dante’s, Melbourne, Feb 7-23

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 26

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Skin Club, Sophie, Linda Erceg

Arts festivals in Australia are going through a process of renewal. In recent years we’ve seen Barrie Kosky and Robyn Archer significantly increase the volume of Australian content in their respective Adelaide festivals in contrast to the standard model operating elsewhere. There’s been greater emphasis on innovation, aided by collaborations between festivals. And there’s been the regional reach of recent Adelaide festivals, Tasmania’s 10 days on the Island and the Queensland Biennial Festival of Music. Access has become a major issue, not only for new and broader audiences but also for artists—witness the Indigenous drive of Peter Sellars’ vision for the 2002 Adelaide Festival. There was an also an increase in the number of free events. Next Wave has long been about access, for young people to create and enjoy art, but this year it’s taken the concept to new heights.

Young people, new work, community engagement, contemporary issues and access are central to the 9th Next Wave Festival. From 17 to 26 May more than 70 digital, dance, online, performance and public art events by, for and with young people will invade venues in, around and above Melbourne. And for the first time it’s all free, a surprising and significant development in an era of enduring economic rationalism.

There are large scale events, exhibitions and other showings that won’t require booking. However audiences still have to book if they want to see performances and participate in forums and workshops. Money will not change hands. Simply register online and request what you want to see. Doubtless, sessions will fill quickly, so booking early is critical.

The 2002 festival sees itself as a collision of art, pop culture, new media, social action, environmental concerns, healthy dissent and, this is interesting, “extreme sport”, and a blurring of the boundaries between audience and participant. The program’s embargoed until the mid-April launch of the festival, but here’s a glimpse of some of the highlights from the 70 premieres created in partnership with young people.

One of the big events will take place on the last day of Next Wave—the planting of 11,000 trees in the suburb of Westmeadows followed by a party in the CBD. The site for the event is an important water catchment area and the planting, part of a 10 year plan, is being produced by Tranceplant, an independent, environmental dance party co-op, in collaboration with Melbourne Water.

As ever new technology plays a substantial role in the festival. Sydney-based sound artist Sophea Lerner will present The Glass Bell, a work 3 years in the making which has been described as a glass waterwall with projections where touch affects sound and image. There’s also interactive martial arts in the shape of Kick the Fractal and VR workshops in art spaces.

Interdisciplinary work will predominate. One of these is a hitchhiker-inspired installation, Human/Machine/Landscape, the result of a collaboration between a visual artist and a documentary filmmaker. The experience will be like a walk-in movie cum sculpture at 45 Downstairs, Melbourne’s newest performance venue (beneath Span Galleries). Another walk-in work will be an inflated chromosome!

Screenings at Cinema Nova include the Megabite Digital Film Project, with help from the ATOM Awards (Australian Teachers of Media). The response from young artists to the call for entries for Megabite has been enormous with more than 150 digital films submitted.

On the performance side of the program, the work is extremely physical, featuring some 25 productions. There’ll be Indigenous dance and The Difficult Company from New Zealand will explore notions of “anti dance.” Look out and look up as one of Melbourne most recognisable architectural and arts icons is invaded by Y Space Company for the 10 days of the festival in a radical outdoor aerial dance event.

In the realm of text there’ll be a focus on comic books and a serious look at independent publishing. Forums covering all aspects of the festival will feature overseas as well as interstate and local speakers.

Next Wave is about access and involvement for individuals and groups. It is also working on a larger scale—towards genuine community engagement. There will be a dozen large public art outcomes which will be unavoidable. These include young people at risk working with artists through long term exchanges in regional and metropolitan Victoria. The resulting installation works move, glow and inflate. Next Wave 2002 looks unique on all fronts.

RealTime/Next Wave

As part of the 2002 program, RealTime editors will work with a team of young writers to produce quick turnaround responses to the festival each day, online and at festival venues on computer printouts. See RT49

Next Wave Festival, Melbourne, May 17-27. For more information go to www.nextwave.org.au

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 27

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Brian Fuata, Karl Velasco, Shelley O’Donnell, Kiss My Fist

photo Heidrun Löhr

Brian Fuata, Karl Velasco, Shelley O’Donnell, Kiss My Fist

The young and talented cast of Kiss My Fist were Brian Fuata, Hannah Furmage, Shelley O’Donnell and Karl Velasco—the Peripheral Vision Company. The context and theory were queer, as was made plain by the apologia in the program—“The title hints at the duality of the good/bad power to transform identity…” etc. Fortunately the work was also inflected with performative values. In the postmodern manner, Kiss My Fist was able to traverse its territory by invoking modernist dramatic traditions.

All the performers presented a character field: a lesbian who longed to be raised to the heights of serial monogamy by a straight woman (O’Donnell); a young Asian man dealing (à la Shirley Bassey) with the break up of his relationship (Velasco); and a Dorothy Porter-type serial killer/detective in a Working Hot world (Furmage). The locus of Fuata’s contribution is less easy to suggest, something he might care to consider; in any case he appeared as a rather anachronistic suburban dad with Elvis longings.

All were powerfully distressed. The audience was initiated into this by Mr Sixties Suburbs (Fuata) taking our tickets in an ecstasy of self-doubt and ushering us onto Ms Wannabe Serial Monogamist barbecuing her ex’s cat (I do hope it was actually a butcher-bought rabbit). We were not allowed to our seats until Mr I-Believe-in-Gay-Monogamy (Velasco) had finished dumping his rage on us.

And so Kiss My Fist continued—with perspicaciously placed ensemble work giving the production a unified dynamic.

It did however seem to enact existential aloneness—Sartre’s characters trapped in the nothingness of hell hurling their anxiety and rage at us like La Fura dels Baus offal. The business was bathed in a glow of Absurdist mania. The always already has been imminent, or some such, was excitingly in process.

The seating was flanked by a screen that threw up slides, comments and eventually a black Cadillac careering across plains and deserts, substantiating the sense announced in the program of the characters ‘hitting the road’. The audience was corralled and moved on, controlled. This lent Kiss my Fist an unnecessary comfort in which the too-easy satire participated. The sniping at gay targets was particularly facile.

By the time we had been advanced through the space to the red velvet proscenium, Kiss my Fist was really ready to confront us. In a theatrical coup, Velasco as a flailing Asian boy puppet related his tale of escape from the sweatshops and his cannibalistic journey as a refugee. The teetering balance of the comic and distressing was most acute at this point and I am not sure Velasco got it right. But then this was the principle on which this clever and accomplished production worked.

Kiss my Fist, consulting director Nigel Kellaway, performers Brian Fuata, Hannah Furmage, Shelley O’Donnell, Karl Velasco, sound designer Gail Priest, video Peter Oldham, lighting designer Clytie Smith, Mardi Gras 2002, Performance Space, Sydney, Feb 14-24

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 27

© Ian Haig; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

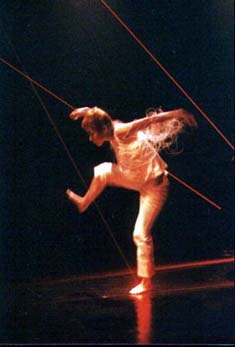

Rosalind Crisp

photo Richard Hughes

Rosalind Crisp

Rosalind Crisp is a Sydney dance practitioner whose Omeo Dance Studio has become an important and influential fixture in a city that lacks both physical space for contemporary dance practice as well as tangible networks and community support. She has recently returned from a trip to Belgium, France, Germany and America with her company stella b. where she made contacts that were both inspiring and beneficial. She returns there in May for at least 12 months, moving between Belgium, Paris and Berlin, and joined from time to time by her collaborators. Erin Brannigan talked to Crisp about travel and its challenges, her current practice and the future of the Omeo Dance Studio.

First let’s discuss your recent trip.

The idea for the trip started when I went to Glasgow for the new moves (new territories) dance festival in 2000. I went on to Belgium after that to visit some people I used to work with there in the early 90s. They were really interested in what I was doing and then a residency came through at the Monty Theatre in Antwerp. It’s quite a new studio above the theatre, curated as an international residency space. I received support for myself and my company, stella b. [currently Nalina Wait, Katy MacDonald and David Corbet] from Monty and from the Australia Council. So when I knew that arrangement was solid I built some other connections and what evolved was a 2 month tour with stella b. beginning with La Biennale du Val de Marne in Paris to showcase traffic, then back to the residency where we showed the results of the research we had done there. Then we returned to Paris and the Centre National de la Danse where we performed traffic and presented the Monty research in a forum. We went on to Berlin and did the same at Tanzfabrik and then I went on to London to do some teaching. Finally I went to the Improvisation Festival in New York then to LA to do a lecture/performance at the University of California, Riverside where dance theorist and practitioner Susan Leigh Foster is based. She invited Andrew Morrish and I to come over and she’s keen to have us back so maybe something else may develop there.

It was just incredible—I didn’t expect anything but was kind of hoping people would be interested in the work and they were. So it was very exciting and we received lots of invitations. Venue producers from Paris who came to see some showings are interested in commissioning me to do new work and I managed to find a manager in Paris who is helping me to get that together. And a lot of things came out of it artistically—especially the residency. It was a fantastic time to be really focused, away from Omeo, board meetings and that sort of thing…I felt really challenged and inspired by the questions they were asking. So it was about getting exposure and stimulus.

What kind of pre-conceptions do you think people had about you as an Australian contemporary dance practitioner?

In Belgium I felt there was a great interest in where I was going personally and the type of inquiry I’m interested in. They’re kind of unorthodox in a way…not so held by ballet and what’s technically correct. There’s a lot of experimentation there and I felt very inspired by that. And in Paris some people said “We’ve seen this…we don’t think it’s new but your personality in the work is really different.” And I thought, “is that Australian or is it me or what?” They were very intrigued and France is where most of the offers have come from for next year.

And then the response in Berlin was completely different again—I felt like they were overwhelmed by the work, as if they hadn’t seen any dance that wasn’t dance theatre. I didn’t feel the same critical engagement with the work. Perhaps the form I’m working with isn’t as familiar…Also, it seemed that there is a lot of interest in work that isn’t being promoted from the Australian end, and not a lot in the Australian work that is being promoted there. But I can’t profess to represent the European perspective. It’s really complex…I felt strongly that the critical dialogue is in Belgium and France and that’s what really attracted me—much more than in Berlin and America. In Brussels I met a couple of ex-students from P.A.R.T.S, the De Keersmaker school, and they’re very inquisitive—their feedback on the work-in-progress was just fantastic. They interrogated us in a genuinely interested and respectful way and were armed with so many tools.

There’s a limited audience here and you’ve been addressing it for some time. Does it feel like time to take your work to new audiences?

It seems quite hard for me to grow here anymore at the moment. I don’t feel that I can get the exposure and the dialogue that I need to challenge me…And the gigs—there’s just not the work here. And that does something else, having a lot of performances. Katy and Nalina grew in leaps and bounds while we were away. It takes a year over there to get the equivalent of 10 years here, so it speeds up the process. I don’t feel negative about Australia. It’s just what’s right at the right time. Being isolated has been fantastic—it’s really allowed me to develop my own voice.

However, there are differences between Australia and Europe that need to be addressed. The decentralisation of funding for dance in Europe means it’s possible to develop the connections that I have made and the networks of interest and support. This is unlike Australia where there is basically only one decision-making body, the Australia Council, deciding who gets to make dance each year. The European model is that funds are given to the venues to distribute. This encourages diversity and a sense that there will always be a place for your particular kind of work. The arbiters of taste who have the power to define what dance is in Australia are very few. And those few producers with money in Sydney, the Opera House Studio and the Sydney Festival define a very limited field through what they support. I do think this situation puts a stranglehold on the development of dance practices here.

What have you been working at—as a solo artist and with your ensemble?

What came up in Monty was that there was material that I needed to go further into—on my own body—before I could communicate those ideas to the other dancers. And that’s tended to be my process, working through physical ideas on my own, getting clearer in my own body and then communicating it to the others, then developing it further with them bouncing to and fro. I found at Monty that it felt premature to make work with them when I felt my body was shifting to another place from theirs, so I felt I needed to pull out for a while.

It’s not that I’ve moved away from the ensemble work, it’s just that I’m doing a solo at the moment. I’ve seen my company stella b. as what I was doing, and in a way it still is. I’m working with the same composer and this solo will be performed with another group work. But I needed to make the shift from the training aspect for a while. Maybe that never goes away—perhaps I’ll find that I’ll always be in a situation where I need to train people. I’ve also been encouraged by some of the French producers to work with some European dancers and see what that does to the way that I’m working, and I find that invitation exciting.

What is the history of the Omeo Dance Studio?

I took on a studio in Annandale in 1994. That was a huge risk—I thought ‘my god, how am I going to find this rent?’ I got through 18 months there and cut my teeth, so it wasn’t such a huge leap to then take on the Newtown space. Omeo Dance Studio is an interesting phenomenon. It’s just evolved without me even noticing it. And I suppose my funding status was reasonably good. I took Omeo on when I knew I had a funded project that had a budget for studio hire. But the first 2 or 3 years were pretty hard and I used to ‘pray’ for money. I lived on nothing really until the Australia Council bestowed a fellowship on me.

And then the studio became self-sufficient?

Well I work at least 12 hours a week in there for it to run, so that’s my labour in exchange for the space. I don’t really want to be the administrator of a venue so I keep it as streamlined as I can. I incorporated it 18 months ago with Andrew Morrish and Silver Gabriel Budd, but it also means we’ve taken on more work because we can. And it’s not just the work on the phone; it’s listening to people, welcoming them and responding to their needs. I did enjoy that in a way because there were a lot of conversations…It does feel that it’s a distraction for me now. I came back from Europe and I realised I’d been like an outrigger ship, dragging all these people along with me—so much effort. But of course I’ve got a lot out of it.

It is a business to the extent that it makes the money that it needs to run. It’s totally non-profit and nobody has been paid for the work that’s been done for the last 6 years. You could rent it out for high rates like other studios, but then it’s just a studio for hire and it doesn’t generate a community. I’ve made the decision to have a sliding scale so people with a ‘studio’ practice can use it for longer hours. So it’s all very tentacled around what I’ve done there. There is a vision—things I’ve decided to do and not to do, and having people contributing to the rent who are people I really want to support.

So what’s going to happen with you being away for the next 12 months?

I now feel I want to keep it going, partly because of the people who want to use it and partly because I actually want to come back and work there. It’s also a structure for me to continue working within, to be able to reconnect with a part of what nourishes me. And I do see things occurring between here and Europe. I don’t feel like I’m going and that that’s the end of it.

I’m still not sure how that will happen but the amazing thing is that Carol Dilley just turned up and I asked her whether she would be interested in managing Omeo and she said she was. She has run a company in Barcelona and she is organised and mature and smart and wants to get to know the dance scene in Sydney…And she wants to keep the studio going and she respects its history, which is great. And it’s also perfect because it’s not exactly a financial concern, but it seems there’s something for her to gain from it. It needs that reason to keep going…so that’s what has happened. So it will still be Omeo Dance Studio.

See Part 2 in RealTime 49

–

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 28

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

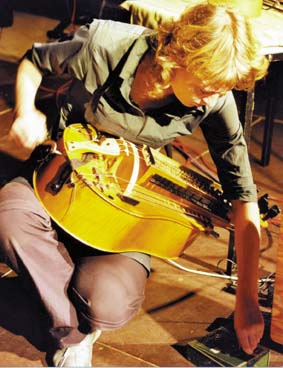

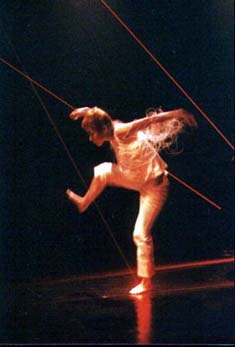

Eme Suzuki, Fragment for Children

Not only do people move in very different ways, their choreographic construction methods and priorities are also quite diverse. Phillip Adams’ Ending #1—part of a major work-to-be, shown in its infancy—afforded a forensic perspective on constructing dance. Whilst some might build a piece through the development of movement, Adams appears to work with an almost fetishistic use of objects, a strong musical presence and an enduring commitment to design, that is, the look of the piece.

Ending #1 begins with a toy plane wiggling along fishing wire the depth of the stage, to the sound of Ligeti’s signature piece for Kubrick’s 2001, A Space Odyssey. Whilst the music suggested an event of great moment, the plane looked absurd in its precarious journey towards the back of the room. A similar tribute to the object occurred when a glow-in-the-dark toy was reverently studied by the performers, then wobbled towards the ceiling.

I had a sense that the movement in Ending #1 was not developed anew but drew upon a now-familiar kinaesthetic which Adams recalls and reworks to fill in the spaces. Adams and Toby Mills danced about in g-strings with fox furs draped around their necks, whilst Brooke Stamp seemed to hang about onstage most of the time—until Adams and Mills enjoined her in a trio which looked faintly pornographic, suggestively lit by a bare light bulb swinging back and forth. I found the piece pretty witty despite its state of choreographic undress. Supposedly about extinction (God knows how that entered this version apart from the dead foxes, and a luminous dinosaur), Ending #1 signals a beginning rather than an ending. I look forward to its evolution.

The second half of Bodyworks Program 3 included performances by 2 Japanese artists, Masami Yurabe and Eme Suzuki. A striking feature of both pieces was the way in which neither drew upon any familiar lexicon of movement. Developed and repeated in a series of poignant movements, Suzuki’s Fragment for Children was very clear, simple yet powerful, her kinaesthetic persona a young girl facing life, dealing with the world in emotional terms. Beginning tentatively, expressing fear and anxiety, the work finished with a series of bows that presented a self at peace. Suzuki’s sincerity and commitment to her theme gave the work its dignity.

Yurabe’s Witness was a very different kind of work, less personal, subject to greater change. Witness begins and ends with a chair. The start was almost clownish but, by the end, the chair became less of a prop and more an object of existential moment. Yurabe’s movement was also quite variable. From comic, anarchic interaction with the chair as a means to enter the performative space, the movement took on a more dancerly character. There was an incredible elegance about his body in motion, also a presence and aliveness which suggested a degree of improvisation. The program notes mention improvised Butoh performance. I felt by the end that I would like to see other works by Yurabe; he has a performative edge that could go many places.

Bodyworks, Program 3, Dancehouse, Melbourne, Feb 20-24

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 29

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Annette Bezor, Blush

The inclusion of Maryanne Lynch’s film Pyjama Girl in the latest offering at the IMA in Brisbane was an astute and successful curatorial decision. A particularly powerful film in its own right Pyjama Girl also provided a catalyst, that set in motion a dialogue between the 4 exhibitions on show.

I may have missed the pivotal role of Pyjama Girl if it had been showing when I first visited the IMA in early February. It is easy to miss such curatorial decisions, since in the most remarkable of exhibitions, the hand of the curator is invisible to the eye. We experience it as ‘just right’ and question no further. However, on my first visit to the IMA, everything was not ‘just right’. The exhibitions of Anne Zahalka (Fortresses and Frontiers), Anne Wallace (High Anxiety) and Annette Bezor (Blush) were up, but there was a strange and strained silence in the space. The projection room was locked and the only indication that Lynch’s work was supposed to be part of the show was a small sign on the door, Maryanne Lynch—Pyjama Girl.

In this context, the work of Zahalka, Wallace and Bezor appeared as a series of 3 independent exhibitions. At one level this impression was understandable. Each show was essentially a solo exhibition. Yet it didn’t quite add up. The combined catalogue and the advertising suggested that there was a greater connection within the show than all the exhibitors sharing “Anne” as part of their name.

Second time round, discordant mechanical sounds seeped from the screening room creating a sense of unease. Zahalka’s light box images of Sydney became more alienated and Wallace’s paintings attained a state of high anxiety. Lynch’s Pyjama Girl had escaped the confines of the projection room and implicated itself in the life of the other work. In this, Pyjama Girl set in motion a powerful dialogue, not just between the works within each artist’s exhibition, but also between the different exhibitions. Bezor’s work, alone, remained aloof to the pull of the Pyjama Girl.

Powerful filmmaking has the potential to collapse the viewer into the medium. In her nonlinear expressionistic narrative of the life and death of Linda Agostini, an Italian immigrant murdered by her husband in the 30s, Lynch’s film implicates the viewer in the drama through being shot from the point of view of the murder victim. In this tightly edited and taut short film, Lynch produces a dread and palpable anxiety that isn’t easy to shake off.

This sense is carried through to the work of Wallace. Borrowing from the tradition of film noir, her paintings are like film stills and in them we experience an unfolding drama. Stylistically, Wallace’s paintings have a strong resonance with Lynch’s film and, at their best, produce a similar psychological tension. In this context, I found myself creating a narrative linking the 2 shows. In the slightly smudged lipstick and vacant expression of the woman in The Indifferent (2000), death seems to lurk. I am transported back to the dramatic life and death of Linda Agostini. But then again, perhaps the character in The Indifferent is precisely that: indifferent. Here the work follows another trajectory—it aches with the loneliness and the isolation of contemporary life. Wallace’s work takes up a conversation with the photographs of Zahalka.

The dislocation and isolation felt in the characters of Wallace’s paintings pervades Zahalka’s work. In her photographs of Sydney, she provides us with iconic images of alienation—isolated human figures overwhelmed by the immensity of the urban landscape. In these light box images, the noise of Sydney is muted and the figures appear to move aimlessly in a strange hyper-real light. The sense of foreboding in the images becomes magnified as the eerie industrial sounds of Lynch’s film insinuate themselves into the space.

The mood of Bezor’s paintings contrasts with the tension created through the rest of the show. Her monumental self-possessed women swell beyond their frames filling the gallery space with a great calm. Given the serene and enigmatic quality emanating from her paintings, it may at first seem odd to program Bezor’s work alongside Lynch, Zahalka and Wallace. However, I found it took the petulant self-possession of Bezor’s paintings to break the psychic tension created in and between the work of the other three.

High Anxiety, Anne Wallace; Pyjama Girl, Maryanne Lynch; Fortresses and Frontiers, Anne Zahalka; Blush, Annette Bezor, IMA Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, Jan 31-March 5

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 30

© Barbara Bolt; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

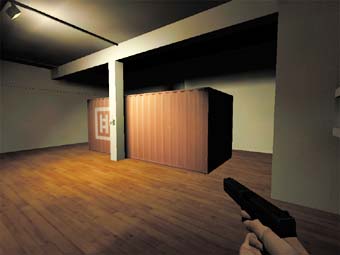

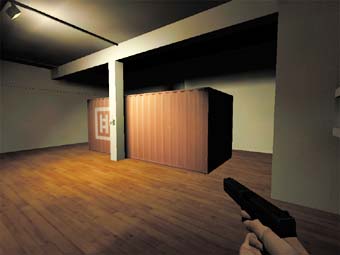

Stephen Honegger and Anthony Hunt, Container (video still)

There’s an emerging niche of visual and sound artists in Melbourne who are actively influenced by computer games and what they represent in contemporary digital culture—which isn’t surprising when you consider the popularity of gaming and Hollywood’s relentless plundering of its imagery; or follow art-game trends in new media art internationally.

Stephen Honegger and Anthony Hunt have worked with the theme of game culture for several years, collaboratively and individually. Soon after graduating with Honours in Painting from RMIT, they installed a Sony PlayStation on a platform at Grey Area, just-out-of-reach, played by whoever was minding the gallery (Gameplay 1998). Hunt has presented facsimiles and ‘doubles’ in various media, while Honegger has sampled game landscapes in his videos, and in Final Fantasies (2002)—with Damiano Bertoli, Amber Cameron, Chad Chatterton and sound artist Julian Oliver—fitted out Gertrude Street contemporary art spaces with 3D sculptural forms lifted from the gaming world (such as concrete blocks and Mario Bros love hearts).

Container, a large-scale sculptural installation at Gertrude Street contemporary art spaces, offered a highly original and sophisticated use of the game logic. More experimental than the form of critique often associated with Australian new media art, Container was more interesting as a result. Entering the gallery, we encountered an object that seemingly didn’t belong: a full-scale rusted metal shipping container, complete with insignia. Container was originally conceived as a 3 screen video projection, but as Hunt confessed, “we were going to have to build lots of walls to make the space dark…and realised a container would be ideal.” Such an imposing art ‘clue’ and a mysterious droning sound from within compels us to look closer. Upon inspection, we discover the container is fabricated entirely from wood, meticulously constructed and painted to match our idea of what it should look like—and precisely matching the iconic image of containers which feature so ubiquitously in computer games.

The dark interior of the container reveals far more, as a video projection immerses us in a narrative generated from the game software Worldcraft. This follows a trend amongst gamers—popularised by mega-games such as Doom (1993) and Quake (1995)—to create and extend existing games using freely available source code (‘shells’) and software. It’s good for the software companies—whole communities develop around their games— fans do the research and development for free. Thankfully, the outcomes aren’t always predictable. The DVD loop in Container begins at night with a first-person perspective onto a detailed, 3D-rendered, pebbled alley at the rear of a warehouse. It’s an aesthetic immediately recognisable from any number of computer games. Clean, jerky camera moves create the sensation of moving through this simulated space. But as the character breaks into the building, we come to realise that what looks like scenery pulled from the latest computer game is, in fact, the gallery itself. What follows is an enticing virtual prowl through the empty upstairs corridor spaces of Gertrude Street artist studios—well known to most visitors.

It’s extraordinary how much mood and realism can be generated from game software. What almost looked like some extraction of hand-held video, as Hunt explained, was all painstakingly modelled in 3D over several months. “It started with the architectural floor plan, and measurements to the millimetre: the door heights, the corridors…everything we needed to know. And then we took photographs of all the surfaces…With modelling, you’re generally just building boxes, and then sticking on a digital image [for texture].” Gertrude Street was the ideal environment for such virtualisation, its corridors and stairs adhering perfectly to the syntax of game modelling. Honegger, who is open about his ambition to work in the game industry, admits that you wouldn’t be able to ‘play’ or interact with Container in its current polygon-inflated form. The point was, “to push it for our own purposes, to do something different with it.”

The narrative moves into surreal mode as we glide down the stairs into the gallery at ground level. The origin of the shipping container is disclosed when the ceiling magically opens and the virtual container slides gently down. The character stalks into the gallery office (complete with rendered versions of the computers, chairs, and catalogues) and collects a handgun foolishly left in one of the office trays. Entering the virtual container, another figure stands—just as we are—watching a screen (now blue and flashing ‘PLAY’). Thus armed, our identification with this character is put under duress. The game has become a ‘first-person shooter’ and it’s too late to intervene: shots are fired, shells pour onto the floor, the figure collapses and blood splashes on the wall. A ‘badly painted’ wall, now revealed as a trace of this gangland-style execution, was the overlooked clue.

Container preserves the basic narrative structure of commercial games—the survival objective and competitive aims—and in this sense is no critique. Yet, experienced alone, it evokes a chilling psychic and temporal displacement reminiscent of one of its inspirations—David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999). Simultaneously alienating and delicious, it adds a rich new dimension to the idea of site-specificity, the gallery, and indeed to the tradition of participatory art.

Container Stephen Honegger & Anthony Hunt, Gertrude Street contemporary art spaces Feb 1 – March 2.

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 31

© Daniel Palmer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Simon Wilton, Lucy Taylor, Mark Minchinton, Natasha Herbert, Margaret Mills, Felicity MacDonald, rehearsals for Still Angela

photo Liz Welch

Simon Wilton, Lucy Taylor, Mark Minchinton, Natasha Herbert, Margaret Mills, Felicity MacDonald, rehearsals for Still Angela

Still Angela premieres for Melbourne’s Playbox in April. Some of the collaborators, writer-director Jenny Kemp, composer Elizabeth Drake and performers Natasha Herbert, Margaret Mills, Lucy Taylor, Mark Minchinton, Ros Warby and Simon Wilton met Mary-Ann Robinson to discuss the evolution of the work.

Some of the team have worked together before on projects such as Call of the Wild (1989) and The Black Sequin Dress (1996). Is this piece is a continuation of earlier work?

Kemp From a writer’s point of view maybe it is…We’ve still got the sense of a woman who is passing through a period of transition and we’ve got once again 4 women playing one woman. Also that sense of an inner and an outer landscape or location, an inner and an outer world and a disjunction between those worlds. And the putting together of the 3 disciplines of sound, choreography and visual theatre.

Minchinton One of the things that’s changed since Call of the Wild’s that the Delvaux [Paul Delvaux the Belgian artist whose work figures in Kemp’s creations] stuff has sedimented. It’s not so overt. And the spatial relationships have changed.

Kemp A difference from then is [choreographer] Helen Herbertson.

Drake We could say that The Black Sequin Dress is like a transition between Call of the Wild and this work, because that was where Helen came in and worked with the actors in a generic way, to actually construct on the floor. It seems that in this one the movement is the driving force, possibly more than the text.

Warby I would say that the text is still the driving force. It feels like it went through a transition from the text to the initial development in which the focus was sort of, throw it on the floor and doing lots of impulse work. Now that the piece is being formulated, with the framing becoming much more refined, that balance has shifted again.

Kemp We are having to behave quite choreographically now in order to place text and movement alongside each other. Even though we are not doing expressive dance movements as such, we’re doing movement that revolves around spatial and temporal choices…because in many of the scenes there are about 5 grids operating. By grid I mean layers of reality or experience happening simultaneously and they are all actually slightly disjunctive in relation to each other. It’s quite complex making the spatial choices so that’s clear to the audience.

Warby Between the spatial and the textual, the layers are quite sophisticated and there are a lot of people on the floor.

Mills I feel that the action, or the movement, or the spatial plan that we are working to is given far more precedence in this one. I think that in Black Sequin there were more discrete events in the text.

Herbert With the ratio of those that speak and those that don’t, at some stages there are 3 characters that aren’t verbal. Helen has provided another language that’s happening non-verbally. At first, as an actor, it’s hard to be aware of all of that because you just want to hook into speaking, but we’re having to stretch that out and be aware of the other language that’s going on.

Kemp Your cue might be someone on the other side of the room doing something…

Herbert Which is nothing to do with the scene that you place yourself in. But it is of course, in another way. The challenge I found was when speaking and engaging in domestic scenes my character is on the move—there’s a certain pace to her and yet I’m having to move fast slowly because you have to react to whatever else is happening.

Kemp Because we’re working with scenes about emotional memory and actual memory, there are times when the actions of the figure Natasha’s playing are being examined by another character and that’s what’s interrupting her, or slowing it down. It doesn’t actually change the nature of her energy but we’re pulling it apart so it can be looked at because it’s being remembered. So that is a really particular task for the performer. Helen said the other day that the girl is not even there in a way, but it’s a slice of the girl, a fragment of a memory of something. And yet there is actually a person out there, a whole person, and they have to be that. But the way we perceive them, or the way they become a part of what’s happening, is as if at times it’s in the back of the brain. We’re trying to get the rhythm of a transition or a catharsis or some inner work that might be taking place.

Warby It’s like trying to get the rhythm of one character through 4 people and 2 languages—choreography and text.

Robinson Can you talk about the process of directing in this way?

Kemp Directing is very complex because one can only direct or be in dialogue with one layer at a time, so there’s been some discomfort in people not being attended to. That’s why when we’re all in the space Helen might be talking to one layer of it and Elizabeth can be talking to another layer of it. We’ve had blocks of time through our creative development when we were all in there and all able to speak.

Drake It’s like it evolves from the inside out.

Herbert We’ve had to discover what it is we’re doing and that has come through our relationship to one another.

Taylor My experience of finding my Angela is that I can’t find the text until I’ve found the physicality. But I can’t find the physicality without text. And then there’s the relationship to the space and everybody else within that. So it’s quite delicate. I’m trying to be patient with myself because it’s quite complex. I’ve got to be conscious of the fact that I’m a memory and someone’s remembering me. I’m in my kitchen—am I remembering me? In the end, I think I just have to be in the kitchen and the form and the content will support the idea.

Kemp Everyone else is this one person, Angela, and Simon is the other person, Jack. What’s that like for you, Simon?

Wilton It shifts according to the different Angelas. It’s not as complex, because I deal with them one at a time and they’re very clearly written scenes, very true situations, very easy to click into.

Taylor It’s wonderful sometimes because you think, am I addressing all aspects of my personality and character? But it doesn’t matter because I’ve got 3 other people to do that for me. I don’t have to do it all.

Kemp It is actually Angela at 3 ages, but we only need one Jack because the Angela’s 3 ages are mutable within her at one age. The younger self is still there as an older self is forming. We’re looking inside Angela and at the outside of Jack. In real terms there might only be one Angela sitting in a kitchen until she gets out and goes on a train journey. And the whole thing could be remembered. There are a number of narrative grids that are activated. They actually do coexist slightly, so people might decide that it means something different to the person sitting next to them, or not be quite sure whether she actually goes to the desert or actually gets off the train. A little bit like in Black Sequin Dress, there are those moments where you’re preparing for the future and you imagine the future. In imagining it, you’re preparing for it.

Robinson Elizabeth, can you tell us about the music, in particular the carousel and the carnival link.

Drake I’ve tried not to follow the text too much but I’m definitely influenced by a certain tone of the language. There’s something quite particular about this work, something kind of pure and raw. So I didn’t want to do something that sounded too sophisticated or too romantic. I wanted it to be just happening over there (in the corner). And the carousel I have worked through because of the connection with horses, and the fact that it exists in a carnival, a setting which is outside our ordinary lives, the place of dreams and dreaming. Mark was also interested in the carnival as a place where things turned upside down, where things aren’t quite what they seem.

Mills The whole thing about the world of nature—rain and earth, mother and memory—there is this layering of meaning in the script that is really strong.

Kemp It’s good that you mention the greater landscape, the sense of the place in nature, the feeling of being connected to the air and trees and sky, as well as being connected to a person. In some ways the play looks at what that is. Quite often when we’re very young, connectedness is attached to another person and there’s not necessarily a strong sense of autonomy. The play is looking at that shift towards autonomy and towards connection with place, or greater landscape. Not that that would cancel out connection with another person, but it’s opening up those possibilities. A kind of rite of passage.

Still Angela, director-writer Jenny Kemp, designer Jacqueline Everitt, composer Elizabeth Drake, choreographer Helen Herbertson, lighting designer David Murray, script consultant Mark Minchinton, film Ben Speth. Creative development and direction in collaboration with Natasha Herbert, Felicity MacDonald, Margaret Mills, Mark Minchinton, Lucy Taylor, Ros Warby, Simon Wilton, Playbox,. The Merlyn Theatre, CUB Malthouse, Melbourne, April 10-27, 8pm; Mon-Tues at 6.30pm.

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 pg. 32

© Mary-Ann Robinson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Blak Inside, a series of Indigenous plays from Victoria, performed at Melbourne’s Playbox to sellout crowds. It’s a vote of confidence in the medium that these writers chose to craft their stories for theatre. I saw 3 of the 5 productions.

Belonging by Tracey Rigney is a story told simply and clearly. Cindy is 13, on the edge of womanhood and not sure where she belongs in her river town. She has friends and she has Pop, a solid, calm old man. Belonging stays with Cindy through a few days of upheaval at the brink of life-changing events. Cindy’s cousin Janice comes to town, looking to party. Tough, seemingly hard, but only 14, Janice does any kind of drug, looking for any kind of fun, hurt and reeling, throwing her body hard at a world that hurts her. She risks great pain to help her feel she can’t be hurt again and she drags Cindy along, needing to tell her how bad, how hard the world is, what a shitty future they have. Cindy’s internal battle is played out simply at the level of what happens to who, but the threads are long and knotted and the story compelling.

Jadah Milroy uses more complex poetic and surreal elements blended with humour to weave together stories of people lost in the city. Crow Fire is the story of Dayna. Raised white, and a public servant, she is frustrated with life and unable to make a difference. Dayna is drawn to Crow, a spiritual force, a big black survivor. Donning her crow costume, she tries to generate a fire in the people she encounters—a politician and her disillusioned banker husband; Yungi, who has come from the desert to the city seeking help; and Tony, her friend.

Casting Doubts explores the question of Aboriginality as it is recognised and performed for broader cultural consumption. A casting agent seeks Aboriginal actors for film roles. Writer Maryanne Sam develops a series of threads around the legitimacy of Aboriginal culture, whether it is denied or embraced. She explores the deep sense of betrayal sometimes felt when working in a cultural industry that insists on a narrow fantasy of the perfect Aborigine—trackers in loincloths, domestic servants who say ‘Sorry missus’ with downcast eyes. To get the job you play the part, but when the ‘trackers’ are in the waiting room, they’re on their mobiles—serious, contemporary dudes. The ‘domestic servant’ is gorgeous, worrying about wearing concealer and crocodile shoes. Are they Aboriginal enough to fit the crap parts written for them? “Him one big hebby pella…me go no furda, boss.” Then back on the mobile and into the suit to resume real life as an Aborigine. Oh well, there’s always Othello. This cleverly constructed play leads us, laughing, through layers of perception about race and image.

Conversations With the Dead is a giant of a play, performed at full stretch over 2 and a half hours by a powerful cast supporting Aaron Pederson in the performance of a lifetime. Richard Frankland’s script and direction drag us to the edges of suffering and pain through a series of conversations with those whose files and stories he worked on during years with the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Just when you can take no more, he eases back with music, some smart jokes and then takes you deeper into the unrelenting pain of Aboriginal deaths and the effects on families across Australia: the suicide attempts, the slashings, the chroming (solvent sniffing), the funerals every week, the disintegration of family life. From the inside, drinking and violence make sense at the end of a long line of breathtaking provocation and grief, the result of being pushed beyond what is tolerable. This is an extraordinary play with not only powerful material but also an understanding of the medium, the use of image, music and non-verbal waves of emotion flooding the audience.

These plays all speak the rich language of people not represented well in Australian culture. The language is tough, quick, hard, Australian, Aboriginal: lots of ‘deadly’ and ‘fullas’ and ‘cuz’. Not a lot of glamour, but lots of humour, some soft, but a lot of it hard, bleak, bitter. Still bloody funny though. These stories cannot be told by outsiders. Insiders in the audience just lit up, amazed to finally see it all up there, life reflected back in full colour.

–