Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

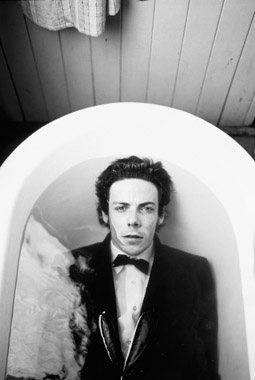

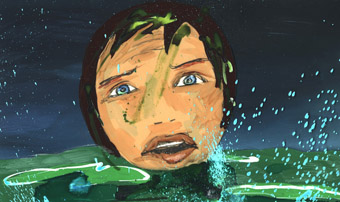

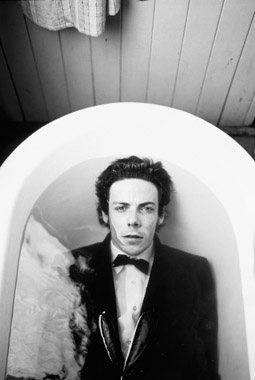

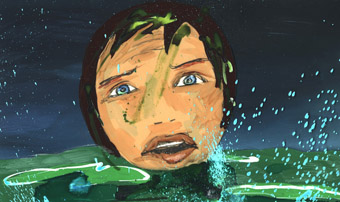

Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba, Memorial Project Nha Trang Vietnam–towards the complex–for the Courageous, the Curious and the Cowards, 2001

The moving image is inescapable. Imagery can be retouched, manipulated or fabricated, it can be projected onto cloth, walls, moulded surfaces, the floor, and through TV and computer screens. It can be cued by the viewer. It can be blunt or surreptitious, naïve or cryptic, romantic or coldly passionless, intellectual or infantile, political or vacuous, archival or hallucinatory. We’re moths in moth heaven—a zone of infinite bright lights, all beckoning. We’re always alert to a potential story.

Much new work is designed for the art museum/gallery, staged in large cubicles and sometimes allied with static elements. Much is televisable or internet/computer transmissible. The form is endlessly variable—quasi-documentary, pictorial imagery, narrative, computer graphic.

Maybe half of the 100 or so artists in the inaugural and meticulously mounted Yokohama Triennale in Japan use screen-based imagery of some kind.

Political concerns are foremost in many works. Mats Hjelm’s Man to Man (Sweden), involving a split screen, made its point by juxtaposing adroitly edited imagery constructed from material left behind by Hjelm’s late father, a documentary maker. It includes scenes from prisons, American POWs fresh from Vietnam condemning the war, a French clown singing a patriotic song, young South American girls playing musical chairs, third world construction workers, cattle starving in an African drought. Hjelm collapses key issues in world politics into a powerful 45-minute montage and shows how they’re still relevant.

In Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Tijuana Projection (Poland/US), female Mexican labourers describe the abuse they have suffered, wearing the camera just under the chin to narrow the image of their faces. The video is of a performance before an audience who watch the women’s faces projected onto a large screen, the women just visible sitting at a table below the screen as they speak.

There is much beauty, even pathos. Fiona Tan’s enchanting St Sebastian (Indonesia/ Netherlands) shows girls from Kyoto practising archery. Across Japan, girls of 20 (the age of adulthood) go through various ceremonies, wearing their ‘coming out’ kimono. The video shows close-ups of faces, hair, skin, the drawing back of the bow and the practising of the movements, as they contemplate the meaning of the ritual.

Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba’s delightful video, Memorial Project Nha Trang Vietnam—towards the complex—for the Courageous, the Curious and the Cowards (Vietnam), shows several young men pulling and riding old Vietnamese tri-shaws underwater. They pause regularly to surface for breath before continuing their work. There follows a scene of the underwater topography, and white tents of mosquito netting, suggesting an empty, submerged village—a moving portrayal of post-colonial Vietnam.

Pipilotti Rist’s fun Related Legs (Yokohama Dandelions) (Switzerland) is in a space hung with white lace curtain materials, onto which are projected images of people, eg a face pressed against a pane of glass. One projector rotates to shift the image from curtain to curtain, the work suggesting something ephemeral, inconsequential. Oladélé Ajiboyé Bamgboyé’s video (Nigeria/UK) is a few minutes of unfocused shots, like an abstract painting that moves, backgrounded by a gentle keyboard soundtrack. Marijke Van Warmerdam’s scratchy, 8mm B&W movie (Netherlands) continuously shows falling blossoms transmuting into leaves and then scattering in the wind, the camera then returning to the tree shedding the blossoms.

There are great animations. Tabaimo’s Japanese Commuter Train (Japan) is a cartoon rear-projected on all sides of a narrow arena—viewers are inside the train with the commuters. Akimoto Kitune’s stunning computer-generated cartoon UFO (Japan) is a surreal trip through space, with a groovy dance track, rear-projected onto an opaque white paper window in a child’s room. Monster heads adorn the room’s walls. While computer animation is the means rather than the end, UFO shows how far the medium has come, and reminds us how central cartoons are.

Sowon Kwon’s oblique work (Korea/US) uses pieces of archival footage of Olympic gymnasts or people walking about, and traces the figures with a coloured line to emphasise the movement. Though recalling Muybridge, the work says more about perception and figure drawing than kinaesthesia or biomechanics. And it defeats association with the subject, eg Nadia Comaneci.

Xing Danwen (China/US) projects New York and Beijing Street scenes into an open cubicle that has a glass-box-like a treasure chest at its entrance. The box houses objects and more projected images counterposing those on the wall. It’s as if we’re inside the artist’s head, watching memories. More literally cranial is Bigert and Bergström’s 3-metre wide hemispherical dome (Sweden) with projections on its inside surface. Equally introspective is Uri Tzaig’s streetlight that projects a metre-wide circular image onto the floor, adjacent to park benches from which people can watch.

There is concern with the architectural and topographical. Florian Claar’s work (Germany/Japan) comprises light projections on sculpted surfaces to suggest landscape. Tacita Dean’s (UK) video, shot inside a revolving restaurant, induces a meditative state as you absorb the banality of the diners, waiters and the slowly shifting background, the outside world as mere scenery. Bahc Yiso (Korea) has roughly cut one wall out of his cubicle, placed it on its side and projects onto it a direct image of the sky above the exhibition hall. Florian Pumhosl’s work (Austria) comprises 3 large projector screens, hanging in space to define a zone, showing videos of buildings in Europe and Madagascar (and fireflies).

Many works combined screen imagery with other elements. Jason Rhoades’ cryptic installation (US) of found and other objects on an artificial lawn included TVs both as object and information source. Oki Keitsuke’s Bodyfuture—have you ever seen your brain? (Japan) has hundreds of white plastic brains on the floor, with CAD 3D illustrations of brains. In La Charme, Emiko Kasahara (Japan/US) covers a floor with circular wigs a metre and a half wide and shows a video of women with matching hair colours sitting on these mats. Candy Factory’s Re:move (Japan) comprises a timber gallows painted a garish yellow, around which are placed wheelchairs and exercise equipment. An adjacent laptop computer displays a video of people learning to use a wheelchair. Candy Factory’s computer-based work is generated collaboratively using the internet.

Yang FuDong’s disturbing work (China) has 3 elements: 4 large screens showing a traditional Chinese garden with superimposed, miniaturised images of naked girls as nymphs/ fairies, while normal-sized people move about obliviously; a cluster of 16 small TVs showing scenes of lovers in a park or men exercising; and 3 other TVs showing scenes suggesting women waiting in a brothel. What separates surveillance, documentary, voyeurism and fantasy?

Rirkrit Tiravanija (Argentina/Thailand/ US/Germany) brought his small van stacked with video players connected to TVs outside it, each with a chair for viewing the videos he shot from the van while driving around Japan. This itinerant artist is more often associated with performance or installation—he once made a replica of his New York apartment and placed it in a Köln museum. Watching his videos is like entering his history, taking part in his interaction with the world.

The Triennale extended outside its exhibition halls and into the adjacent shopping mall. Aernout Mik (Netherlands) depicted a stock market floor with stricken traders amid the carnage of a crash. This surreal work repeated seamlessly, suggesting to bemused shoppers an endless cycle.

The screen is even mocked. Alexandra Ranner’s glass-enclosed room (Germany), containing seating arranged to view a lamp post visible through a window, evokes the absent, impotent television. Adel Abessemed’s Adel has resigned (Algeria/US) is an endlessly repeating 5 second image of a woman’s face as she states “Adel has resigned”, shown on a TV monitor that sits in the corner of an empty room. The artist indeed appears to have taken his leave. With time, this mantra might be hypnotic or meditative, but I didn’t wait.

William Kentridge’s haunting work (South Africa) is a glass bathroom-cabinet, with a rear projection inside it, showing animations he makes by photographing sequences of his drawings—news headlines interspersed with depictions of the troubled citizen.

The video is a panopticon. It can condense the photographic, the narrative, the performative and the representationally abstract. The aesthetic is flexible, indeterminate. If there is any story, it’s typically remote, conjectural. If not, you look for symbol and metaphor, or respond reflexively. The screen image’s power lies in its ability to shift our thinking and emotions, and it is becoming a dominant artform. Amidst more conventional artworks, screen works stand out in Yokohama.

Yokohama 2001 International Triennale of Contemporary Art, Mega Wave—Towards a New Synthesis, Yokohama, Japan, Sept 2 – Nov 11

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 29

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

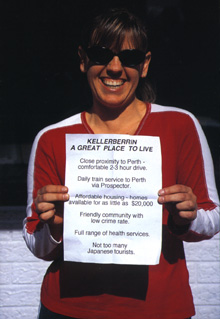

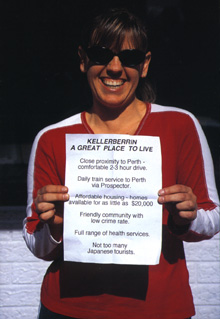

Carolyn Rundell, Shadowlands Virtual Skies

It’s often said that innovation and dynamism occur not at the centre of systems, but at the periphery. Try applying this notion to metropolitan and regional art scenes and you’ll often find an uneasy silence. At least that’s been my experience since arriving in Warrnambool, 3 hours south west of Melbourne.

Logic in these parts deems the distance from Melbourne to Warrnambool at least twice that of the reverse journey so that much of what occurs in terms of the visual arts in this region remains unremarked or, at worst, invisible to those elsewhere.

So, what is happening on this strip of English landscape transposed to the shores of the Southern Ocean? The town of Warrnambool boasts a Deakin University campus nestled between river and paddock. Graduates from the Visual Arts school here are regularly represented in the National Art exhibition, Hatched, hosted by the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts.

Warrnambool Gallery’s permanent collection contains turn of the century European salon paintings, colonial landscapes including works of Eugene von Geurhard and Louis Buvelot, and other historic images of the Shipwreck Coast region. What may surprise is the collection’s strong representation of works of avant-garde Modernism including artists Albert Tucker, Sidney Nolan, Charles Blackman and Joy Hester as well as those of contemporary artists Juan Davila, Barbara Hanrahan and Ray Arnold. In addition, 2 temporary spaces host works from leading artists as well as touring exhibitions. Monash University’s Telling Tales: The Child in Contemporary Photography (see RT39 p9) is a recent example of the latter, featuring Anne Ferran’s series Carnal Knowledge, Ronnie Van Hout ‘s Mephitis and Bill Henson’s Untitled 1983/1984.

The gallery deviates from the conventional white cube in its encouragement of community and emerging artists through the availability (at a small fee) of a temporary exhibition space, the Alan Lane Community Gallery. Though risky in many ways, this generative move unearths some interesting contemporary practices and talent.

Evidence of this was seen in October, with Tate Plozza Radford’s exhibition Junk Food, a raw but coherent body of works. Using spray paint, Radford uses a process of marking and layering to produce a palimpsest effect or visual overlays evoking ancient cave paintings and alleyway graffiti. Temporal and spatial boundaries are blurred formally and thematically, through a superimposition of pristine dinosaur terrains, urban bleakscapes and the clutter of contemporary existence. This body of work may be viewed as an allegory of the planet’s progressive/regressive occupation by human and other forms of life.

Showing at the same time in the larger gallery was the Deakin University annual exhibition (by design or chance) entitled Regula Fries. The show displays an interesting intersection between fine art, photography and graphic design forged through Deakin University’s Visual Arts program that allows students to work across these areas throughout their undergraduate studies.

Another recent exhibition/event Slessar’s/4 Works (which deserves more space than can be given here) suggests the attribute of dogged tenacity is not lacking amongst local artists Adam Harding, Amanda Fewell, Chelsey Reis and Carolyn Rundell. The initiative culminated in a body of site-specific works interrogating the role of the gallery system as arbiter, and allowing the makers and audience to explore emergent relationships between art practice, space/place and community.

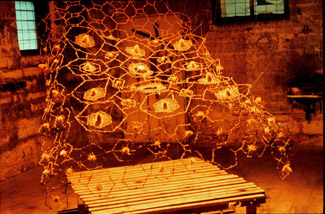

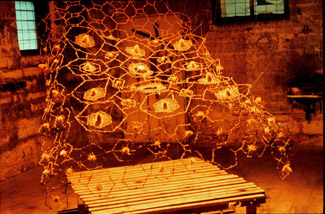

Slessar’s Motor Electric Shop, built in Koroit Street at the turn of the century—dark, begrimed and somewhat decrepit—was up for lease with no takers. With persistence the artists were able to secure the building free of charge for 6 weeks.

Works produced by Fewell and Reis emerge as a direct response to the nature of the building as a place of male labour, and demonstrate how craft can operate simultaneously as aesthetic conceptual and critical practice. Fewell’s intricately woven rolls of cash register dockets allude to the commercial history of the site. The alchemical visual transformation of waste paper into rich and delicate fabric is a validation of women’s labour where once only men toiled.

Reis took inspiration from discarded oil-stained T-shirts and fragments of texts—graffiti and notes—left by workmen, converting them into finely embroidered garments. Producing the work from and in the space, Reis questions the logic of Western attitudes to work and applies what she terms a “low-tech, hand-made approach, linking the aesthetics of craft to meaningful work practice.”

Rundell, known for her monolithic sculptural works woven from barbed wire, continues the dialogue with Shadow Lands Virtual Skies, a massive quilt woven from barbed wire and suspended from the ceiling over a bed within a darkened space. She views domestic space and landscape as strong influences on our psyche and comments, “The work attempts to illustrate the paradox of love and control in both domestic space and the wider Australian landscape.”

Harding (remembered for prior interventions through his Black Cats and other projects in Geelong) is new to the town and, without a car, is bemused by the proliferation of roundabouts and traffic barriers thwarting walkers and drivers. Assuming ownership of the roundabout as a front yard, the first phase of his work involved knitting a pastel-coloured mohair cover for steel barriers at the nearby corner—a performance which amused passers-by. Other responses included some suspicion from the local constabulary, discomforted by interference with civic infrastructure and a strong belief that knitting is not a blokey thing to do. The mohair tubing was later filled with white wadding and installed in the building as a precarious railing, producing comic contrast to an unyielding mechanical darkness.

The Slessar’s project afforded a new connection with the building’s history and its departed community. For some, it seemed to satisfy a yearning for something rough, gritty and perhaps bohemian. The makeshift bar and kitchen offered a place for artists and curious visitors to linger for a yarn and ponder anew the notion of change, transformation and this business called art.

Interest and activity around the site has led a local restaurateur to take up a lease to convert Slessar’s Electric Motor Shop into a bistro restaurant—art slipping, almost seamlessly, into life?

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 30

© Estelle Barrett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In correct syntax brings together the work of 3 artists, Melbourne writer Mammad Aidani, Singapore based installation artist Matthew Ngui, who sometimes lives in Perth, and Tasmanian textile artist Greg Leong, currently Launceston based. The curators, Niki Vouis and Mehmet Adil, presented the artists with a series of artistic challenges.

First, the artists were asked to engage thoughtfully and deeply with the work of the others. In the next stage they worked collaboratively to make new installation work in which they incorporated visual and other textual references to each other’s artistic oeuvre. Spatiality, space sharing and attendant questions of power were related issues with which the artists had to contend, since the new work commissioned had to be site specific. The resulting installation work was custom-made for Adelaide’s tiny and rather idiosyncratic Nexus Gallery space.

In response to this curatorial brief, Hong Kong-born Greg Leong chose to incorporate an ancient Persian motif, the boteh symbol, into his work. The boteh apparently originated in Persia then traversed India, Central Asia, the Caucasus and Asia Minor before winding up in Scotland where eventually it morphed into the well known and relatively contemporary paisley design. Leong’s mixed media quilts, suspended from the ceiling of this small gallery, speak eloquently to the possibilities of a borderless world based on globalised kinship systems where identities are neither singular nor monolithic but are routinely and complexly intersecting and hyphenated. In rich red Chinese silk and brocade, inscribed with texts of different verses by poet Mammad Aidani, the works look for all the world like gorgeous inverted seahorses floating and bobbing underwater.

The entire exhibition gave me the feeling of finding myself below sea level, encountering treasures rich and rare in a dark and quiet space. The aquarium-like feel of the space and the exhibition itself was reinforced by the continuous flickering presence of the live video installation by Matthew Ngui projecting Mammad Aidani’s elegantly hand-written ink-on-paper poems in Farsi script. I loved the work that Ngui and Iranian-born Aidani jointly created. Aidani’s Poem in Persian (2001, ink on paper), reconfigured by Ngui and projected on to the wall of the gallery, was ethereal, memorable and moving. The fleeting, sensual qualities of their installation contrasted interestingly with the other more literally material works.

All of the works here show that migration, late capitalism and personal markers including gender, ethnicity, ‘race’ and sexuality combine to produce complex identities at the nexus of a set of sometimes contradictory elements. If art is about transcending the spaces into which one is born, both physical and metaphorical, and embarking upon aesthetic adventures of identity, this exhibition succeeds par excellence.

This is a thinking person’s exhibition. The curators have consciously drawn an analogy between visual images and other kinds of texts, especially linguistic ones. Specifically, the exhibition conveys the idea that all artistic traditions (for example, ‘Chinese’, ‘Persian’, ‘European’) have an underlying grammar or ‘syntax’. Just as there are rules governing spoken and written expression, the structure and visual patterns or possible arrangements in any given ‘visual language’ are subject to certain cultural parameters.

While this is a challengeable assertion, as there are limitations with respect to how far such a linguistic analogy can be extended to visual media, the idea raises a plethora of fascinating, supplementary questions. For instance, are these new, hybrid artistic works akin to linguistic pidgins and creoles? If the latter, each of these works could be understood as greater than the sum of its component parts, regarded as unique transcultural creations. Or are they simply arbitrary agglutinations of various visual and cultural signs and symbols, the artistic equivalent of, say, broken English? There is a suggestion in the accompanying brochure that this may be the case, and that lying in the interstices and cracks of seemingly inadequate spoken language are unappreciated riches. Or are the works on display here merely tricksy, along the lines of Pig Latin, for example?

Thanks to Adil and Vouis throwing down the curatorial gauntlet, these culturally diverse artists have created installations that give us a good deal to look at and think through with no instant gratification to be had, visually or in other ways! Of course, there’s nothing new about artists ‘pinching’ or appropriating visual patterns, ideas and styles from other cultures and traditions in the course of cultural contact. What is different about In correct syntax is that the artists were actually directed to do so for the purposes of this exhibition. Now that’s a different ball game.

In correct syntax, curated by Mehmet Adil & Niki Vouis, artists Matthew Ngui, Mammad Aidani, Greg Leong, Nexus Gallery, Lions Arts Centre, Adelaide, Sept 6 – Oct 7

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 30

© Christine Nicholls; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

I was lookin back to see if you were lookin back at me

To see me lookin back at you

Massive Attack

‘Observation’, it seems safe to say, has made it to zeitgeist status. Whether it’s the bizarre phenomenon of watching the making of Man Down (the ‘film’ shot by Big Brother inmates) or the maddeningly abstract formulations of Niklas Luhmann (German sociologist and ur-reflexivity theorist) observation is the critical stance of choice across a range of artistic practices and cultural sites. The video art program Wet and Dry explored this cultural trope—the “lingua franca of hyper referentiality” (curators)—with edgy wit and a disquieting aesthetic. Curated by Ian Haig and Dominic Redfern, the event brought together recent work from a diverse set of Australian and international screen-based video artists.

Wet and Dry was organised conceptually according to a number of technological, formal, and thematic criteria and the trope of observation played itself out in different ways over the 2-night screening. For many of the pieces within the Wet program this meant self-consciousness about the pop-cultural heritage of video art. Ferrum 5000 (directed by Steve Doughton), for example, clashes Busby Berkleyesque references with images that recall The Residents together with 50s sci-fi ‘green goo’ iconography. And I Cried by Cassandra Tytler makes observation an explicit concern in its exploration of ‘celebrity’ and the longing for stardom. Drawing from televisual culture, with an obvious fondness for 50s crime narratives and 60s set design, Tytler’s piece is both homage to and critique of the ‘cult’ of the image. Video diarist supremo George Kuchar is, of course, rather a cult figure himself. The 2 works screened, Culinary Linkage and Art Asylum, are poignantly kitsch studies of trash culture and TV land: “beautiful people emoting” as Kuchar puts it. Emoting is something Kuchar does extremely well. But it’s not quite the emotion of Sunset Beach. His sensibility is pitched somewhere between Samuel Beckett and Eddie the Egg Lady—the excruciating passage of time and the pathos of bodily function. Sadie Benning’s Aerobicide, a music video for the band Julie Ruin is, ostensibly, a critique of sales pitches, focus groups, motivation seminars, target audiences and the rest of the corporate grammar of consumerism: the “Girls Rule (kind of) strategy” to use their ironic phrase. But the video looks so goddamn good—gaudy colours, modernist architecture and fluorescent office lighting—that it’s hard to resist the urge to join in the whiteboard fun. And pleasure, as all good visual culture theorists know, is intimately connected with the business of ‘watching.’

The Dry program brought fresh, albeit vexing, interpretation to the ‘scopic’ desire of screen-based art practice. Hood by Klaus vom Bruch explores the spectral and uncanny forces behind visual iteration and feedback. A woman’s face is caught mid-glance as she turns her head. The shot is played again and again, till you get the sneaking suspicion she is actually looking back at that which plays her back. Mesmerising and intractable, this image, her slightly anxious face, her gaze, forms a self-referential loop from which it is difficult to disengage. If Hood is slightly vexatious in its attention to the materialities of screen culture, its quiet insistence to look at rather than through the interface, then Joseph Hyde’s Zoetrope is relentless. Here, we find Laura Mulvey’s theories on the pleasure of visual phenomenology pushed to ear splitting and pupil constricting extremes. Zoetrope seems almost pornographic. Yet there are no undressed bodies, no unexpected flashes of flesh to excite our carnal appetites and hence shame the viewer/voyeur. No, what is pornographic about Hyde’s work is the way it focuses on observation sans object. Twenty-one long minutes of raging, screaming feedback and migraine-inducing white noise creates claustrophobic soundscapes and optical distress. Zoetrope transforms the romantic experience of watching something (narrative development, character formation, scenic construction) to the somatic reality of neurological response. Watching becomes an intransitive verb. Theoretically very pleasing; corporeally—not so much.

One of the last works screened was pleasing on both counts. Conceptually adroit and visually stimulating, Involuntary Reception by Kristin Lucas is about a woman afflicted with an “enormous electromagnetic field.” The formal arrangement of the video is double imaged, reflecting her ambivalence about technological mediation. Because of her extreme sensitivity to electromagnetic signals this character, played by Lucas, can crash computers, read people’s minds or make cats fry as she explains in a beautifully sparse, monotone voice: “Yeah, I’ve had a pet before. You just have to be careful not to…pet them. Because that just builds the static energy and…I guess the static charge was just too much for her…I’d start petting her and the static would build up. And then one day…it was just too much. Love kills. Love kills.” Indeed, a fried cat is iconic of this video art program itself: half wet, half dry, disquieting but compelling to watch.

Wet & Dry: International video art, curated by Ian Haig and Dominic Redfern, presented by City of Melbourne & Centre for Contemporary Photography, Cinemedia @ Treasury Theatre, Melbourne, Sept 21 & 22

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 32

© Esther Milne; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

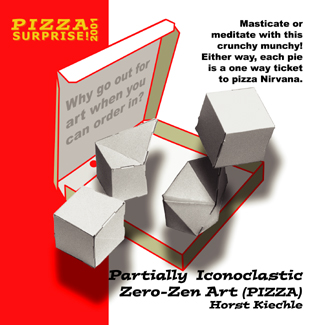

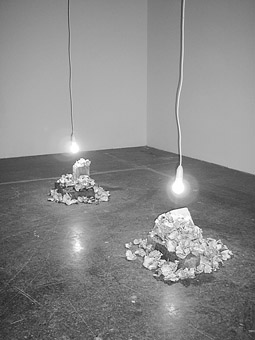

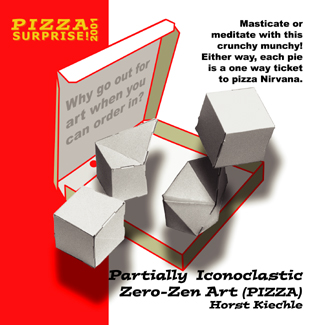

Horst Kiechle, Pizza Surprise

Reviewing Pizza Surprise! is an exercise in restraint. An abundance of culinary and other lame clichés spring to mind, willing me to make them manifest. The reality of the Pizza Surprise! project and its outcomes, however, is that though the work and its literal delivery are based on a packaged concept of convenience, it is far too cunning to be so easily dispatched.

Pizza Surprise! is unabashedly what it is, a commercial, marketed-to-the-eyeballs, good-value visual arts project, and much more. It is a national and international event, a travelling show, and a low-price, egalitarian and accessible exhibition for your lounge-room table. Conceived by local Perth curators and recently pizza delivery chicks, Michelle Glaser and Katie Major (Art to Go), Pizza Surprise! is, above all its superfluous and incidental concerns, a collection of damn fine art. Seven artists including Bruce Slatter (my personal choice), Martine Corompt, Bevan Honey, Mari Velonaki, Scanner, Horst Kiechle and Sam Collins tackled the compressed white, flip-top cube with work that spanned the supernatural to the structural.

A strange kind of value judgement starts to operate when art is offered, home-delivered in a family-sized pizza box, for $19.95 (+GST). The generic nature of presentation, the online order form and automated responses solicit hasty decision. I knew I had to have one but further scrutiny of the work would have prompted me to order the lot! Therein lies the paradox; as a show of 25×7 packaged multiples, it has proved unattractive to artistic, commercial and cultural entities (who should be kicking themselves), but immensely popular within the gp.

The work by no means suffers for this, as all artists engage with the pizza box’s spatial and commercial paradigms with incisive, deconstructive and, yes, entertaining work. Sam Collins’ Appliance for the Decoration of a Common Void is a neat composition of circuitry and wires with a discrete switch that, when plugged into a TV, begins to scroll a number of test-pattern orientated compositions, creating a changing abstract-art feature for any living-room.

Another technologically-orientated work, Pizza Aphonia by Mari Velonaki, uses text formed by a number of LEDs that light up when the box is opened. This work, deconstructing an intimate letter within 25 pizza boxes, has resonances with the film noir secret briefcase. Martine Corompt’s gruesomely cute Household Names includes a cannibalistic cartoon adventure of 4 physically distorted, wannabe pop-starlets and a pink, rubbery doll of the same extended proportions.

Bevan Honey takes the framing and placing concerns of The Hot Sell into a zone of questioning the consumer experience. His work includes a piece of timber thickly layered with varnish that covers a random, linear pattern in black paint. The reverse of the pizza box includes detailed instructions for hanging that suggest a considered approach to placement in the home.

Cardboard constructivist Horst Kiechle’s Partially Iconoclastic Zero-Zen Art (PIZZA) uses the pizza box as a starting point for the folding of a series of boxes, from cube to non-cube. These works are carefully cut in the same material as the pizza box, and rely on the customer following specific instructions for their creation. UK sound artist Scanner’s Spread recreates a soundtrack of someone-else’s everyday, transplanted into the home of another.

A condition of buying a Pizza Surprise is that the owner must send Art to Go a document of its installation. My Bruce Slatter Painter’s Palette Ouija Board deserves a home-movie séance replete with candles and much foaming of the mouth to conjure one of the “…really great dead painters.”

Pizza Surprise! curated by Art to Go (Katie Major & Michelle Glaser), various homes in regional areas & metropolitan cities of Australia, Oct 23-Nov 7

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 32

© Bec Dean; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lindsay Vickery

Lindsay Vickery has been based in Perth for the last 10 of his 15 years composing and performing New Music including works for acoustic and electronic instruments in interactive electronic, improvised or fully notated settings, ranging from solo pieces to opera. He has been commissioned by numerous groups and has performed in Holland, Norway, Germany England, the USA and across Australia. In December he will be resident again at STEIM (Amsterdam) working on an interactive video project and in January he will undertake a 9 states tour of the US culminating in a residency at the Center for Experimental Music and Intermedia (CEMI) at the University of Northern Texas. Vickery also lectures in music at the Western Australian Conservatorium of Music where he founded the laboratory Study for Research in Performance Technology.

…one can observe that numerous important elements coincide with real facts with a strange recurrence that is therefore disconcerting. And, while other elements of the narrative stray deliberately away from those facts, they always do so in so suspicious a manner that one is forced to see there is a systematic intent, as though some secret motive had dictated those changes and those inventions.

The genesis of Lindsay Vickery’s creation, Rendez-vous—an Opera Noir, is reflected in these opening lines. Adapted from Alain Robbe-Grillet’s novel Djinn, Rendez-vous has strayed with systematic intent through the decade of its making. Over coffee, between teaching and rehearsals, Vickery spoke about his latest work.

“At the end of ‘93 Warwick Stengards, who was the Artistic Director of Pocket Opera, came to see me. He was interested in commissioning a work. I actually suggested a number of things before Rendez-vous because Djinn was quite a difficult work to adapt…”—Vickery gives a short laugh “…Stengards wasn’t interested in any of those but he thought Rendez-vous sounded like a great idea.

“So that conversation resulted in me writing a libretto. We applied for money to write a score. I wrote a score…Rendez-vous was completed back in 1995 so that gives a measure of how difficult it is to put on new opera…particularly in Perth. There is no infrastructure to put on work of this nature. So, there was a workshop period back then in ‘95. Then Pocket Opera went bust and Magnetic Pig picked it up and did a concert version, just the music (in ‘97) which was so we could get recordings to push the work forward. Since then it’s been a period of collecting bits and pieces of grants to develop this part, grants to develop that part, collaborations with various people. Finally, this last 18 months or so has seen Black Swan (Theatre Company) coming on board, Tura (Events Company) coming on board.

“We had a meeting the other day where all of the various partners who are involved in this work were in the same room. And, you know, it really is indicative of the difficulty of doing this that it has taken 6 or 7 major collaborators to come together to be able to put this thing on.”

Vickery, along with Cathy Travers and Taryn Fiebig, has been performing excerpts from the opera for the past 5 years.

“That’s been quite an important element in keeping the work alive. One of the songs has been recorded for Musica Viva and has been touring schools and that kind of thing.” He laughs. “It is so innocuous that it has been to primary schools.”

There have been other diversions for Rendez-vous along the way.

“Just in frustration really. A couple of years ago I took some ideas from it and made a separate piece called Noir which used the Miburi jump suit as a midi controller, controlling lights. Noir didn’t use any text appropriated from Rendez-vous, Robbe-Grillet’s text; it was an original text. But there is a little tiny bit of the music from Noir which I pinched for the car chase scene. But essentially Noir was a work, a separate work, a quite closely related second-cousin.”

When asked if, at that stage, he just wanted to see something completed, even if it was a second cousin, Vickery replied, “Yes. It felt really great to be in this room with people who were all pointing in the same direction, and keen to see a work finally up and running.”

Now Rendez-vous is up and running. At the time of the interview it was only days away from rehearsals and all of the video footage, for the virtual set, had been shot and was being edited.

“We have a really great team of people working on it. Obviously, like so many contemporary artists, they are not being paid a heap of money. Well, particularly Vikki Wilson of Retarded Eye. We came up with the idea of having virtual sets, projected sets, maybe 3 years ago, and she and I have expended an enormous amount of energy discussing how we were going to create this work and what it was going to look like. She’s got a great visual sense and a really encyclopaedic knowledge of the postmodern literature scene, the postmodern theory scene, which comes through in her work in a way that’s not overbearing. She creates really incredibly beautiful images.

“Talya [Masel, the director] was in on the process right from the beginning. She ran the first workshop back in ‘95. She has been in on the various stages and transformations, incarnations, of the work. She’s been ideal; she’s definitely got a sense of French literature and postmodernist literature.

“Andrew Broadbent, who plays Simon, has a music-theatre background. Taryn Fiebig, she crosses over between the classical music and contemporary music streams, and also music theatre. Then there is Kathryn McCusker who is firmly planted in the Australian Opera, in the classical tradition. So there is a kind of hierarchy there which is reflected in the characters they play.”

Vickery’s “kind of hierarchy” also contributes to the development of the opera’s narrative and its structure.

“In film noir where everybody is talking at the bottom of their range, and everybody is being as cool as possible, is as far away as you can get from opera where everyone is talking at the top of their voices, as loud as they possibly can. We needed a transition through that. So, we picked up on the increasing complexity that you get in the novel by having the characters begin at the bottom of their range in a style that is much closer to natural speaking, and they gradually go into more and more heightened speaking and eventually full singing. I hope that this will be a seamless thing. That’s part of why we cast the way we did.”

Vickery concludes, “Tos Mahoney (see RT 41 p32) at Tura (Events Company) has been really important. I think this is the most complicated single work that has been put on by Tura”—looking across the table Vickery laughs—”this is definitely the most complicated work that I have put on.” Then, suddenly serious, “I hope the momentum from putting something like this together can remain for other projects out there. After this, hopefully, they’ll know it can be done successfully.”

At the end of the year Vickery will be taking QuickTime footage of Rendez-vous to a number of venues and producers in the US. The University of Northern Texas has already made enquiries about staging it.

Lindsay Vickery, Rendez-vous—an Opera Noir, Rechabites Hall,

Perth, Nov 21 – 25

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 33

© Andrew Beck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

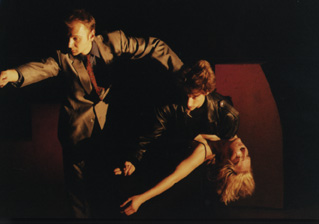

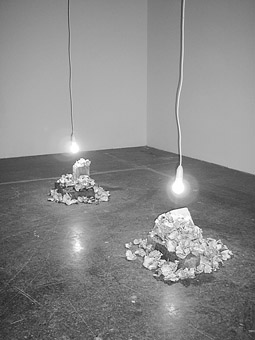

Sonia Leber & David Chesworth, The Masters Voice

photo Sonia Leber

Sonia Leber & David Chesworth, The Masters Voice

Visitors to Canberra, or new arrivals, are often anxious to find out where ‘town’ is, where they are in relation to the middle of things, the action, the hub, the urban focus. There’s a common conversation that goes along the lines of, “So where’s the city?” “Well…” (apologetically) “there’s Civic…” Civic is the diffuse middle of this diffuse city—a loose mix of malls, cafes and bus terminals; visitors greet it with some suspicion, as if there’s actually a real urban centre somewhere else which is being kept from them.

The retail and restaurant cluster is around Garema Place, the wide pedestrian plaza that is truly, in social, street-life terms, the middle of town. Its image has been dominated by petty crime and drugs, until recently; the Place has been ‘cleaned up,’ and local government seems intent on encouraging a more lively and non-threatening public space. There’s certainly a pulse now: lots of fire-twirling, the odd band, packs of skateboarders and freestyle bike riders, hopping around the steps and benches like biomechanical goats. As well, public sculptures have been multiplying in the Place precinct, part of a public art program being run by local government. The latest of these is The Master’s Voice, a sound installation by Melbourne-based collaborators David Chesworth and Sonia Leber.

The work is physically almost surreptitious: 11 straps of stainless steel grille, inset into the pavement and up an adjacent wall. It borders a pedestrian thoroughfare through low-key retail and cafes, a transitional space. Crouching below waist level, it trips up passers-by, induces double-takes, private puzzled glances. It calls out: “Come ‘ere…gedaround ya lazy dog / Chook-chook-chook-chook! / Back…back…back…good boy, Whoa!” It addresses us directly, in a language and a sonic shape that is completely familiar. It’s just that we’re not usually the addressee, here. A throng of animal-voices: calls, exhortations, orders, signals, admonishments, affectionate jibes. In fact they’re real-world recordings of people talking to their animals, with the sonic presence of the animals themselves edited out. There’s a kind of hole in the air where an animal should be, but it’s only occasionally clear what kind of animal, and anyway it keeps changing. A phantom menagerie, chooks, dogs, elephants, horses, who-knows-what. That’s what passing humans walk into, what alerts and draws them in, a virtual form made from silly, anthropomorphised animal-talk, but a form which points to the real presence of one of those inscrutable ‘others.’

Leber and Chesworth have edited the calls together into short compositions, layered sequences which follow a passerby the length of the work. There are arrangements of sense and subject but especially sound: pitch, contour, cadence, rhythm. The ‘sensible’ inflections of speech get stretched into wild glisses and warbling melisma; syllables shorten into abstract sonic punctuation. There’s a bit of outright mimesis, growls and clucks and budgie whistles, but more often the calls work 2 strata at once, language and sound, human and animal. The words are there as a scaffolding for the sonic forms—the elements which do the behavioural work—but also for the speaker’s own benefit, a warmly ironic monologue. “You’re not going to be able to walk, your stomach’s that big…You aren’t…Eh?” At the same time these calls are full of questions, invitations to conversation, spaces for exchange; there’s this urge for an interchange, which in the absence of an articulate partner, puts words in its mouth, or maw.

So these candid, charged interspecies moments emerge from inconspicuous slots in a mallscape; their sonic shapes stand out against the ‘public’ murmur of social verbosity. As Tony MacGregor (Executive Producer, Radio Eye, ABC Radio National) pointed out at the work’s opening, Canberra is nominally a location for public, social, civilised speech; yet the House of Reps is dubbed the “bear pit.” Meanwhile these real interchanges have an immediacy that the scripted drivel of most political discourse lacks. Most striking, though, is the presence which the work projects, the way it subtly deforms this coolly anthropocentric public plaza, turning civilised language into silly noises, and turning people, momentarily, into animals.

The Master’s Voice, sound installation by Sonia Leber & David Chesworth in association with H2o architects, Pocket Park, Corner Garema Place & Akuna Street, Civic, Canberra.

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 33

© Mitchell Whitelaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

At the beginning of Toru Takemitsu’s work, Stanza II for amplified harp and tape, Marshall McGuire stopped to retune his harp. The simple gesture of standing, quietly checking, plucking, and moving on to the next strings held a quiet kind of physicality and inherent theatre, that had the potential to serve as a source of inspiration for the mixed media content of the 3 concerts I attended in September, as part of the Sydney Spring Festival.

That work was a festival highlight. The tape track of the Takemitsu, written/recorded in 1971, was exciting and rich. Something in it grabbed the imagination and flung it up into the air. The harp (both treated in realtime and appearing on tape) sounded as if it had been left alone in a dusty corner of a city warehouse where the daily movements of the sun across its strings and frame, and the shifting humidity of a decade’s seasons, had caused it to disintegrate…popping to itself, the wood creaks, the strings sound brittle, a bat flying past brushes the strings and they shimmer and flick apart. This was organic and dark music, almost vocal, as the harp cried out its fracturing. We heard the city outside the windows, and voices, briefly, as they peered into the room—though they didn’t seem to see the pieces of the harp in the corner.

This work came at the end of the Twentieth Century Harp concert, featuring a selection of favourites from renowned contemporary harpist Marshall McGuire. Also a delight during that concert was Berio’s Sequenza II—always a pleasure to hear the recognisable gestures of a Berio Sequenza, of which he wrote several, for various solo instruments. Kaija Saariaho’s Fall also had electronic elements, echoing from the corners of the room, flirting briefly with the lower registers of the instrument—I never knew a harp could growl. And McGuire playing Franco Donatoni’s Marches at times created a physical effect—a swoon of harp swirls made the back of my head tingle as with the first draw on a cigarette and, there again, a pleasurable exploration of the colours of the instrument’s lower registers.

The video projections throughout the concert, by Nicole Lee, worked reasonably well with the Takemitsu—images of a dark-eyed and serious young man moving through a cityscape. We’d seen him earlier throughout the concert, turning in slow motion to face us.

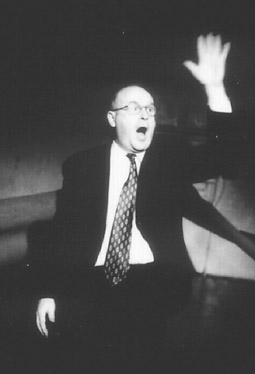

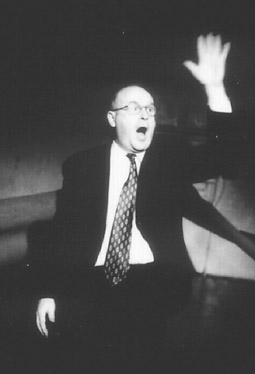

At the Colin Bright evening, The Wild Boys, I enjoyed the playful and ironic Stalin, with the recorded voice of Jas H Duke working itself into hysteria, crying out the name of the Russian dictator like a child for his mother, or a lover for his partner. And given that it was just a week after the bombing of the World Trade Centre in New York, and consequent Australian government posturing, the re-presentation of Amanda Stewart’s 1988 Bicentenial work work, N.aim, was horrifyingly prescient. Stewart’s presence in the audience, reminded us how welcome a live performance would have been.

The recordings introduced the artist to the listener before Bright manipulated them. They also added a much needed change of texture through the concert, as I found The Wild Boys, Ratsinkafka and There Ain’t No Harps in Hell, Angel too long, too loud, and too didactic. Musically they were all bombardment, with little tonal variety. And call me old-fashioned, but there’s something odd and frustrating about hearing great musicians (Sandy Evans, Marjery Smith, Synergy Percussion et al) on tape in a concert. The one live appearance from Marshall McGuire for There Ain’t No Harps in Hell, Angel was a disappointment—outdated and predictable in its references. AC/DC with Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus? Give me a break.

Towards the end of the festival, Delia Silvan’s program, Night Vision, was musically enjoyable, with exquisite performances. Roger Woodward’s 2 Chopin Nocturnes were like a caress, McGuire pensive and perfect in Ludovico Einaudi’s Stanza and From Where?, and cellist David Pereira played Carl Vine’s work with tape, Inner World, with precision and appropriately withheld emotion.

But the dance didn’t work for me. Delia Silvan is a fine dancer and her first attempt at choreography was sometimes pretty, but overall somewhat clichéd in its subject matter—women and darkness—and its choreography. Meanwhile the music inevitably becomes secondary—an emotional support team for the main game. An odd thing in a music festival.

For this concert, as with the other 2, I found the imposition of other elements upon the music exactly that—an imposition. Looking for points of integration of purpose in each I could find very few—what did manifest for a moment in Lee’s video work, and that of Dean Edwards during the Colin Bright concert, was soon evaporated by monotonous repetition.

Watching digitally rendered red dots split and multiply I wondered at their function. Similarly I ended up averting my eyes from the repeated replays of Lee walking up a beach. Can someone tell me the point of using digitally made landscapes through which the viewer is rushed ever onwards, as if in a video game (Edwards). A comment on the sterility of the way we interpret the world around us, or the mindlessness of video games…or are the images themselves sterile, with no connection to the psyche of the audience, nor the artist? Abstract images appeared throughout the Bright concert, combined with more immediately graspable, repeated images—newspaper clippings, drawings of Stalin, dollar signs, Aboriginal children, the Greenpeace web address. So does the repetition indicate that the music is all the same? Or that the issues are? Either way, if you can say it once why say it again, and again?

These 3 concerts demonstrated the fundamental problem of contemporary music’s continuing disconnection from contemporary performance practice. Musicians are prone to repeating, in their ignorance, the practices of awkward, early days of collaboration. If Sydney Spring is to stake a claim in this worthwhile territory, then the organisers should think about adding a specialist curator to its artistic team to help realise its admirable intentions. Otherwise, keep it simple and stick to the music.

12th Sydney Spring International Festival of New Music: The Wild Boys, Colin Bright, Sept 18; Twentieth Century Harp, Sept 20; Night Vision, Sept 22, The Studio, Sydney Opera House

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 35

© Gretchen Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Erik Griswold, Sarah Pirie (Clocked Out Duo) & Craig Foltz Other Planes

The Sydney Spring International Festival of New Music is an intimate garden where new works sprout side by side with modernist rarities—old seeds newly planted and nurtured. A small audience of admirers and the curious gather in the Sydney Opera House’s The Studio. For a significant part of the festival we are joined by a larger audience of ABC radio listeners. We clap like buggery to make them feel there’s a big turnout. Once again it’s a surprise that Sydney Spring can survive on the small audiences and a modest budget while yielding a richly coloured crop of quality performances planted by Artistic Director Roger Woodward and Executive Producer Barry Plews. But it does, attracting grant and sponsorships and some concerts pulling sizeable and appreciative audiences.

The pick of the bunch were the concerts by Clocked Out Duo, Erik Griswold, Ensemble Sirius, Marshall McGuire, and the Homage to the Iannis Xenakis, who died in February this year. A feature of this year’s Sydney Spring was the interplay between music and other media—video, visual art works, dance and combinations of these. Compared with the 2000 festival’s Exile, these were less developed and sometimes less than ideal combinations (see Gretchen Miller’s response above). Nonetheless they were indicative not only of healthy explorations in hybridity but also of a widespread concern to reach new audiences intrigued by multimedia possibilities.

Russian Futurism, Sept 14, 8.00pm

This proved an unusual opening concert, providing in part a prelude to Russian musical Futurism (or Constructivism as it is sometimes called as in the Sitsky Adelaide Festival concerts) with works from Skryabin, his son Julian (who drowned aged 11) and Pasternak (who gave up music to write). Skryabin's Feuillet d'album (1910) is his first venture into atonality. Roger Woodward plays an earlier work of intriguing beauty of the same title (1905). The son's Two Preludes (1918) seem even more prescient of the music to come, yet sustain the beauty of his father's dark romanticism. Then we were plunged into the middle of Russian Futurism with the 4 piano Symphonie: Ainsi parlait Zarathoustre (Thus spake Zarathustra; 1929-30) by Ivan Vishnegradzky. A musical mystic following Skryabin, the composer employed quartertones and microtones (a preoccupation too of our contemporary, the Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina) to evoke cosmic consciousness, in this case 2 pianos tuned to normal pitch, 2 in quarter and 3-quarter semitones. The effect is extraordinary, initially like a bevy of slightly out of tune pianolas exercising scales on the edge of chaos. The second part is rhythmically rich but even more harmonically disturbing, the tonal shifts sounding like massive re-tunings of a master instrument. The brave pianists were Robert Curry, Daniel Herscovitch, Erzsbet Marosszky and Stephanie McCallum. The second part of the concert was a great debut for the Grand Masonic Russian Chamber Choir of Sydney, conduced by Artistic Director Piotr Raspopov. How the post-World War II works they performed fitted under the Futurism mantle wasn't clear. Shostakovitch was a contemporary of the Futurists and a fellow member of the doomed Association of Contemporary Music—some early works, like Symphonies 2 and 4, share the robust sense of machine and chaotic speed associated with Futurism. However, the Poems 5, 6 & 7 from Ten Poems on Texts by Revolutionary Poets are elegaic, seamless constructions that allow the choir to demonstrate its range from classically rich Russian basses to lucid sopranos. The short work by Georgi Sviridov, Sacred Love, was remarkable only for its long, layered closing chord. by now I was beginning to think that Futurism had indeed been thoroughly purged by Stalin. However, the next 2 works, Da-di-da and Sunset Music, both by Valeri Gavrilan, suggested a tradition kept alive with their mix of the sung and the spoken, whoops and laughter and an insistent if heavily punctuated rhythmic drive. A dogged cuteness indicated that a radical inheritance was not be found here. What we got was a choir with a lot of promise and at its best in the Shostakovitch.

ACME Jazz Unit, Sept 14, 10.30pm

In the first of the late night jazz offerings from Sydney Spring, Adelaide's ACME Jazz Unit performed with polish and exuberance and was rewarded with rapturous applause. That's a good outcome, considering that the band's natural home would appear to a be a quality jazz club and that we'd of our drinks on entering The Studio. Vocalist Libby O'Donovan reckoned it would have been nice to have cigarette smoke too, but only for the atmosphere. The sense of musicians speaking the same language was evident from the beginning. In tightly scored, short works, improvisation was not a priority, but the many nuances that adorned the works yielded an engaging conversational ease. O'Donovan's range rose from raunchy belter to music theatre mezzo to a soft, all-sweetness-and-light soprano (thankfully without American vowels). While looking spectacular in her high heel sneakers, ultra-punk-spike hair and slick black plastic 3-quarter coat, she moved little, energy focused and embodied in the voice and on sharing the stage with the instrumentalists. Aside from one all too brief avant garde-ish contribution, Space: Tone Poem, the works, all composed by band members, were pretty safe for a new music festival, the pleasure mostly coming from the sheer dexterity of the delivery. There were exceptions, the gentle, opening number Harvest Time erupted into wild vocal riffs against the minimalist pulse of piano and drum. In Man of Sorrow, Julian Ferraretto's violin sang sinuously in the tradition of Stephan Grapelli. In his own La Zia Zangara (The Gypsy Aunt) the same voice spoke with a dynamic flamenco accent, shades of Chick Corea's Spanish phase. Throughout, bassist Shireen Khemlani proved an audience favorite with her right-on-the note melodic inventiveness and fluency while drummer Mario Marino provided clear lines of support with plenty of dextrous treble and no signs of heavy footedness. Group leader and key composer, Deanna Djuri, is an eloquent, melodic pianist, deftly creating a big city, bluesy Sweet Lullaby with a soaring vocal line for O'Donovan. Djuric's prize-winning, gospel-inflected Don't Let Go allowed the vocalist even further off the leash in the final number. The concert's centre-piece was Soap, a set of songs (Suspicion, Love, Jealous, Revenge) commissioned from Adelaide composer Angelina Zucco. Moments of musical inventiveness and committed performances didn't quite prevent it feeling like a sketch for a music theatre work and one in search of some real substance. ACME Jazz Unit made an impression that only frequent visits will sustain, bridging pop, jazz and music theatre with a coherent vision.

Ensemble Sirius, Sept 15, 8.15pm

The American duo (Michael Fowler, piano, keyboards; Stuart Gerber, percussion) play Stockhausen with a simple, elegant theatricality and a bracing, lucid sonic intensity. They first gesture their way to their instruments to perform 6 of the star signs from Tierkreis (Zodiac, 1975). Nasenflügeltanz (1983/88), the engrossing duo version for percussion and synthesizer of part of the huge 7-opera cycle, Licht, had percussionist Gerber singing Lucifer’s lines, punctuated with orchestrated hand signalling. The best known work on the program, Kontakte (Contacts, 1959-60) sounded less familiar as a piano, tape and percussion work than as an electronic score, but was nonetheless rivetting.

Colin Bright, Wild Boys, Sept 18, 8.15pm

A sampling of Bright's works played vividly over the sound system was accompanied by video images projected on a central screen and slide collages on screens to either side. The curious mix of videogame-like digital imagery and agitprop collage (Dean Edwards) was too busy and sometimes too literally illustrative to ever enter into a dynamic relationship with scores that were already full on, replete with their own texts (the late, great Chas H Duke, William Burroughs, Amanda Stewart) and powerful aural imagery. Bright is a unique and provocative voice, but going visual needs care—ears wide, eyes shut.

Erik Griswold, Sept 19th, 8.15pm

Erik Griswold is not Jo Dudley. Dudley was still in Germany. Griswold filled in, replacing Dudley’s sensual and whimsical theatricality with one of the most rewarding and intense performances of the festival. The tall, lean pianist-composer hovered over narrow stretches of his keyboard and picked and pounded out Other Planes: trance music for prepared piano. Rubber wedges, bolts, weights and business cards variously contributed to the alchemical transformation of furious, minimal clusters into eerie harmonics and distant half-heard melodies, sudden evocations of gamelan and marimba. American writer Craig Foltz provided text and voice via phone line for the title work, the apocalyptic intoning of the banalities of the everyday focused on air travel made for unsettling September 11 associations. Visual artists Sarah Pirie framed Griswold with treated fabrics pierced by light, echoing the detail of the compositions and the preparation of the piano.

Marshall McGuire, 20th Century Harp, Sept 20, 8.15pm

Rough Magic (ABC Classics 456 696-2) is rarely away from my CD player. This concert proved a great companion program providing more 20th century music for the harp, extending McGuire’s project into powerful works with amplification and tapes. Gentle works—the twinkling harmonies of Tounier’s Vers la source dans le bois (1922), the seductively song-like Hindemith Sonata (1939), Peggy Glanville-Hicks’ pastoral Sonata for Harp (1952)—preceded Berio’s lyrical and theatrical Sequenza II (1962), shot through with harmonics and abrupt punctuations (slaps, taps, sudden dampings), Kaija Saariaho’s Fall (1991), metallic, big and pulsing, with great rumblings and sweeps of the strings, Donatoni’s Marches (1979 and on the Rough Magic CD), an obsessive, hesitant dance with its passages of intense quiet pitted against grand guignol hyperbole, and Takemitsu’s Stanza II (1971), unexpectedly alternating aggression and reflection (with gagaku resonances), strings burring, chords bell-like, declamatory, fusing with blocks of haunting pre-recorded sound. The home video banality of the accompanying screen material (Nicole Lee) provided neither companionship nor counterpoint for the delicacy of the more introspective works or the grand gestures of the larger ones.

Clocked Out Duo, Sept 21, 8.15pm

This proved to be the most idiosyncratic concert of the festival, a striking and original fusion of minimalist and jazz (and other) impulses realised in piano (Erik Griswold) and percussion (Vanessa Tomlinson). The concert reproduced track by track their CD Clocked Out Duo: Every Night the Same Dream (COP-CD001) including the sublime title work (Griswold) with its engaging recurrent neo-boogie drive and percussive chatter, Graeme Leak’s lilting dialogue between a Vietnamese newsreader and solo percussion, Tomlinson’s intense musical monologue, Practice, Griswold’s Bonedance (with seed pod rattles tied to the pianist’s wrists, first driven and then ruminatory), his beautiful and, here and there, unusually romantic Hypnotic Strains (“Varese/Xenakis inspired percussion” with piano improvisation) and Warren Burt’s Beat Generation in the California Coastal Ranges. If Griswold’s highly focussed rapid fire pianism often magically conjures a clear, transcendent musical line, Burt starts out with and sustains a gently pulsing note (“the beating of one note against another as moving sine waves undulate against delicate vibraphone chords” says the program note). It carries you along, sound and texture everything, the vibraphone a Buddhist bell beneath Big Sur pines.

Delia Silvan, Night Vision, Sept 22, 8.30pm

There are still those choreographers who employ a selection of musical compositions, often excerpts from substantial works, as a framework for their own creation. It's a rather tired tradition, especially in an era where composers, sound designers and dj-composers are creating challenging scores that may well entail any number of appropiated works but which add up to challenging totalities. In Night Vision Delia Silvan dances to a collection of compositions played live that make for an occasionally interesting but unlikely concert program and Silvan's choreography is not strong enough to provide the requisite coherence. The intention is that the work comprise a “series of interconnected 'duets'” (with Marshall McGuire, the Clocked Out Duo, Roger Woodward and David Pereria playing works by Einadu, Griswold, Chopin and Vine respectively). The relationships seemed all too circumstantial. The design (Silvan and Craig Clifford) with its 2 columns of moveable light (suspended perspex poles through-lit from the top) however suggests potential, framing and enabling the choreography's obsessive dance with the self.

Homage to Iannis Xenakis, Sept 23, 6.00pm

Two things were striking in this extraordinary event performed by Roger Woodward, Stephanie McCallum, Vanessa Tomlinson, Nathan Waks and Edward Neeman. One was the demands made by Xenakis on the performers, whether on piano, cello or percussion, as if possessing them from beyond, enforcing the tortuous stretch of arms and hands in the rapid traversal of keyboards, Vanessa Tomlinson’s furious playing-as-dance, Woodward’s manipulation of an original score comprising massive pages. The other defining element was an enduring sense of the compositions as aural architecture, the conjuring of vast imaginary spaces sounding ever more accessible and inhabitable, ever more beautiful with age. A fitting conclusion to the 12th Sydney Spring.

12th Sydney Spring International Festival of New Music, The Studio, Sydney Opera House, September 14

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 35

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

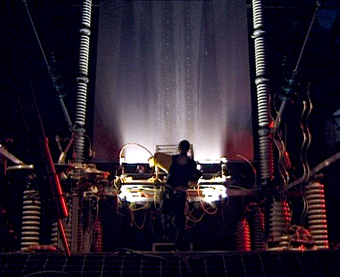

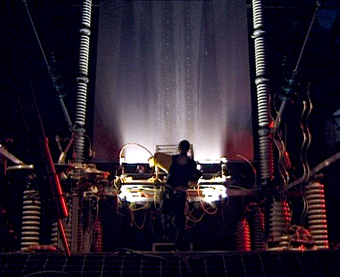

Christian Eggen, Dark Matter

photo A Higgins

Christian Eggen, Dark Matter

As a guest of Brisbane’s ELISION at the world premiere of Dark Matter I offer the following not as a review, but as personal and descriptive account of the work and the feelings and thoughts it provoked. The work is the joint creation of the ELISION ensemble and the Norwegian CIKADA ensemble, their conductor Christian Eggen, and the primary collaborators, British composer Richard Barrett and Norwegian visual artist Per Inge Bjørlo working with Daryl Buckley, the artistic Director of ELISION.

Dark Matter is a massive and mysterious work. It embraces its audience and eludes it, unites and divides it, hectors and seduces it. It solves nothing, it opens up everything. This is the dialectic you ride for 75 minutes if you have the patience and the stamina, or the will to surrender. I wrestled and played with Dark Matter over 2 performances, worried at and relished it. Treasured its intelligence and its stark beauty.

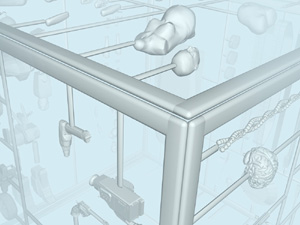

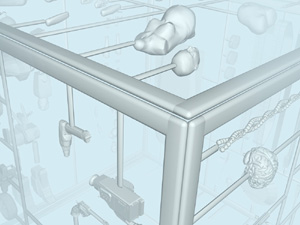

Installations come in all sizes. This was a huge one, a performative installation in the Brisbane Powerhouse’s large theatre, the seating removed, the space a concert hall, an unfamiliar church, a panopticon, at the very least all of these. On entering you don’t know where to place yourself. This is something like a concert hall: there are musical instruments at one end, seats of a kind at the other, but each is a sculpted space. The musical terrain is of platforms, a brightly lit box and a tank behind a glass wall, all at various elevations: the audience plane is flat but on it are metal cages, benches and tubular stools, short and sharp-edged. Glaring lights on tall stands assail us as we seek out seats. Some of the seats in the cages (evoking miners’ lifts) face away from the musicians. Between a row of stools on one side and benches on another, a metal sheet is lined with truncated cones topped with glass disks. It looks dangerous, an object for contemplation, as is the whole space for the duration of the performance.

Not a note has been played, but the performance has already begun as the audience enter and transform and become the installation. They move about, selecting seats on which they place the industrial cloth handed them as they enter. The light is too bright, they change seats. Or they stay and, choosing only to listen, tie on the masks they find on their seats. Or they sit to find themselves facing a small metal-cased monitor on a stand on which they or their fellow audience members appear. They are watched as they watch. Visual artist Per Inge Bjørlo has divided the audience from itself.

Bjørlo has transformed concert hall into gallery, given a listening audience objects, screens and other people to contemplate. The objects might be made from industrial detritus but they appear honed and burnished. Harsh quartz halogen light scatters through wire mesh and heavy grilles, fusing the whole into one architecture. But its wholeness is racked with interference, a scientific phenomenon that Per Inge Bjørlo sees his own art sharing with composer Richard Barrett’s. This is an installation that interrupts the view, compels the audience to mask, or seek out new spaces, to sit amidst the musicians, or stand or lie anywhere, to hear the play of electronics from very different vantage points. The audience can choose to visually and aurally compose its response to Dark Matter, to the push and pull of invisible material.

In the very centre of the floor, dominating the space, is a tall, circular platform, its base a metre and half tower of metal grille through which scatters white light. Above a stool, a score, small loudspeakers facing in: the conductor’s pulpit, the centre of this panopticon. Already in the austerity of the materials, the dazzling purity of the light, an audience atomised into contemplative individuals, there’s a sense of church, an unfamiliar one, not holy, not home to dogma (as Barrett ever stresses), but mysterious, enquiring, as art should be. Barrett in a program note refers to Dark Matter as a “cosmological oratorio”, and given the range of his sources and inspirations from various creation myths through arcane Renaissance thinkers and doers to Samuel Beckett’s painfully optimistic but entropic vision, it’s apt.

Even before we hear a note of music (which confirms and changes everything), another association constellates round the design. The metallic austerity, the light, suggest laboratory, or reactor. And when the music commences, as Barrett says, Christian Eggen becomes a conductor in more senses than one. Composer and visual artist visited a particle accelerator in Switzerland as part of their preparation. Bjørlo imbues the space with the stark beauty of a Protestant church and an industrial ugliness suggesting danger—an aesthetic we have embraced since at least the early 20th century and in which Nature has no easy place.

Behind the conductor and in a large cage of their own (ironies abound) sit composer Barrett and sound engineer Michael Hewes, outputting the electronic and amplified sounds that dialogue and aurally dance with and challenge the acoustic instruments before them. In the major electronic passages it is fascinating to watch Barrett leaning over his small cluster of pads and keyboards, fingers flying, hands hovering, striking. The sounds generated and meeting with those of the acoustic instruments build another space in and about the installation often beyond description, often beyond the sometimes too familiar cosmic sci-fi sounds of electronics. Like the installation and its evocations, individual and collective sounds, phrases and passages and whole movements have a rare sonic purity, found also in Deborah Kayser’s soprano meditations or her adroitly spare reading of Beckett, and even in the rapidly articulated (mock shamanistic was it?) wordless litany from contrabass clarinettist Carl Rossman.

It is however the questing voice of the electric guitar that tests the prevailing tone of chaos constantly if barely ordered. It is here that the composer—the artist as analogous to the scientist, as Barrett would like to see him/her—takes us somewhere very different. Curiously, in the entropic finale to the work, after all else has faded in a sustained, sublime reverie, and the last words of Beckett’s Sounds have left us, the electric guitar alone sings on, but it is fading, being faded, until the plug is pulled, leaving only the faint plucking of a near soundless instrument. Barrett, in a dialogue with Buckley in the printed program puts it more precisely:

…6 superimposed guitar parts…create a chaotic and meaningless tangle of notes against which the live guitar struggles aggressively but is ultimately defeated, first in its attempt to make sense of things and finally in its attempt to make any sound at all, as its amplification is withdrawn, turning it from the loudest instrument in the ensemble to the quietest.

For a complex musical work, in which like jazz you can lose yourself, lose track, find your way again, Barrett’s Dark Matter is lucidly constructed, canonical, interpolated with these astonishing electric guitar passages (transmissions) from Daryl Buckley, which progress from delicate harmonics to huge chordal shifts and dense buzzings and burrings (that seem to evoke but avoid the idiom of jazz and rock greats) and apocalyptic hymnings that nothing else in the work approaches, and nor should it. Fittingly the guitarist sits at the highest point of the ensemble atop a metal platform mounted on what appears to be a huge abstract concrete foot pointing into the space; behind the guitarist a screen fills the vast theatre wall, a single light radiating nova-like across it.

Barrett describes Dark Matter as modular, as unfinished. This first version will be augmented with new passages and re-shaped in future versions. I’ll be keen to hear how they work, whether this art as investigation will continue to take the same shape it does now: creation and its instabilities; erudite investigations, beautiful orderings, cosmic imaginings; the word and its end; musical entropy. The passage from the Big Bang or Lucretian Chaos or Creation to Entropy or the Day of Judgement or various brands of static Eternity is an all too familiar macro-narrative. Umberto Eco has mused, “..what if the story of the big bang were a tale as fantastic as the gnostic account that insisted the universe was generated by the lapsus of a clumsy demiurge?” Of course, Dark Matter’s rich complexities and artistic illogic defy such broad patterning moment by dramatic moment.

Whatever thoughts (and anxieties) Dark Matter gives rise to, the work is already a deeply memorable one for me. It was a pleasure to see a work on such a scale, of such beauty, with such a range of invention and skilful realisation emanating from a long and sustained international collaboration.

This report on Dark Matter is part of a RealTime-ELISION ensemble joint venture. At the invitation of ELISION, Keith Gallasch travelled to Brisbane to see 2 performances of the work and participated in a public forum in which he and musicologist Richard Toop interviewed composer Richard Barrett. The performance of Dark Matter was recorded for radio by the ABC. We hope to soon reproduce the printed program’s Richard Barrett-Daryl Buckley dialogue on our website.

Dark Matter, ELISION and CIKADA ensembles in association with the Brisbane Powerhouse, composer Richard Barrett, visual artist Per Inge Bjørlo, conductor Christian Eggen, sound engineer Michael Hewes; Brisbane Powerhouse, Nov 16-18

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001 pg. 36

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A major shift in the phenomenology of modern listening is marked by the distinction between Swann’s infatuation with the “little phrase” from the Vinteuil sonata in Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, and Hans Castorp’s absorption in gramophone recordings in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. For Swann the evanescent “little phrase” remains always different from itself, not only because of variations in performance, but because the successive occasions on which he hears it are separated by the years of his own existence. For Castorp, on the other hand, the obsessive replaying of his favourite records marks an attempt to escape time, to attain within the temporal flow of music an arrested state in which every note is always played “just so.” In both cases this musical infatuation gradually decays to an intellectual and emotional nullity, not because familiarity breeds contempt, but because the interiorisation of music absolves the listener from the difficult labour of listening.

We might characterise modernity as producing a simultaneous disappearance and proliferation of music in our lives, for if there has been a steady decline in participatory musicianship, at the same time we are more than ever surrounded by music in its recorded forms. The concert form, exemplified by the chamber recital, might be seen as an intermediate stage in this division of musical labour, between the involved listening of musical participation and the distracted listening of a saturated musical environment.

Since 1995 the 4 Adelaide-based composers Raymond Chapman-Smith, Quentin Grant, David Kotlowy and John Polglase, known collectively as The Firm, have been refining a kind of pure and uncompromising musical event. They see themselves as working in the chamber tradition, of a serious intellectual music granted leave from music’s traditional subordination to social functions, where the audience is brought together not to pray or celebrate or even necessarily be entertained, but simply to listen.

In a musical equivalent of the artist-run gallery, The Firm organise their concerts themselves, from the programming of the music to the more mundane details like mailing lists and tickets. Always on a tight budget, they dedicate their resources to hiring the best performers available. They have built up a strong local audience and have featured regularly at the Adelaide Festival and Barossa Music Festival. Through recordings and broadcasts they have gained increasing recognition nationally and overseas, with Chapman-Smith, Grant and Polglase having recently been commissioned to write pieces for the Schoenberg sesquicentenary celebrations at the Vienna Festival.

Chapman-Smith’s work is probably the most austerely intellectual of the four. Although minimalism influenced his earlier work, his primary musical filiation is with the Second Viennese School of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern. Other inspirations also derive from the German romantic tradition, such as the quasi-mystical abstraction of Klee and Mondrian, or the metaphysical lyricism of Paul Celan’s poetry. Chapman-Smith’s approach is to rework the classical forms of an older tradition, such as Bach’s tautly symmetrical Baroque dance-forms, within the rigorous language of a reinvented serialism. Far from a dry academic exercise, however, the highly restrictive parameters Chapman-Smith sets himself work to temper the extreme expressiveness of his ‘raw material’, giving his music a restrained but powerful eloquence.

Grant’s work is the most diverse. He identifies 3 distinct styles in his music, which he tends to use in alternation rather than trying to draw them together into some reconciled mode of expression. The first is an aggressive expressionism, in which a percussive element derived from minimalism drives a kind of grunge exploration of the dark side of the human psyche. As a psychological antidote to this material, Grant’s second style is more serene, a mystical attempt to achieve what he calls “whiteness”—a spare, open, aesthetic deriving from Eastern Orthodox religious music. Grant’s third style, which has emerged more fully in recent years, is a yearning or nostalgic Romanticism which owes much to central European composers such as Leos Janacek or Pavel Haas, in which the simplicity and openness of the melodic and harmonic elements lends the music simultaneously a great vulnerability and resilience.

Kotlowy’s work is intensely focused on the act of listening. Inspired in part by Eastern meditative traditions, as well as Cage and Feldman, the basic structure of his music is extremely simple, single distinct notes sounded separately between periods of silence. There is no ‘line’, no stepping from one note to another, nor is there ‘development’, in the sense that the middle or the end of the piece is qualitatively different from the beginning. Instead, Kotlowy concentrates a microscopic focus on the character of each note in isolation, making audible its distant delicate harmonic resonances, but also drawing attention to the incidental variations in the act of playing. It resembles Chinese calligraphy, in that the artist’s gestures leave large areas of the canvas untouched. A recent string quartet is a typical example, with each player given a series of sustained notes to be played pianissimo. The notes overlap to create delicate shifts of harmonic texture, but developmental flow is quietly resisted, creating a sense of being in time rather than moving through it.