Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

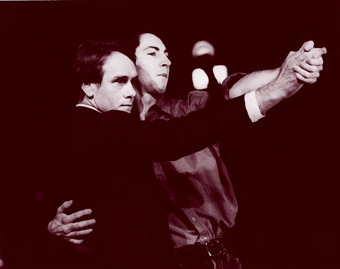

George Khut

photo Simon Cuthbert

George Khut

George (Poonkhin) Khut is an Australian artist currently based in Sydney after working extensively in Tasmania. His best known sound installation Pillowsongs (see RT24 p46) was first exhibited in Hobart (1998) and has since been re-worked and shown in Melbourne at Temple Studios (1999), Sydney at Gallery 4A (1999) and Darwin at 24 HR ART (2000).

More recently he has been working on a series of commissions and collaborations with performer Wendy McPhee, which will culminate in their new multi-channel video installation Night Shift. The project has received assistance from the Australia Council’s New Media Fund (at the creative development stage and as a new work) for its premiere at the Brisbane Powerhouse in 2002. Khut describes the installation as “incorporating alleged techniques of subliminal media such as split second imagery, sub-audible utterance, and rhythm, in a meditation on solitude and feminine performativity. The sound works are concerned primarily with an experience of sound at a deeply personal level, re-synthesising the ‘silences’ or noises of the urban soundscape into a series of surreal ‘interior tableaux’, and recalling moments of intense and aurally focused solitude and silence such as meditation, convalescence, insomnia, waiting rooms, and late night travel.” I caught up with him during his most recent trip to Hobart where he is working on Censored with McPhee and director Deborah Pollard for the 10 Days on the Island festival.

Poonkhin, how did you get started?

I was born in Adelaide in 1969 and grew up in the inner-city suburbs. I started off noodling around with old cassette players, echo machines and Moog synthesisers in the mid 80s, and this process of tweaking material remains at the core of my creative process.

Your mother is Anglo-Australian and your dad is Chinese-Malaysian. Are there perceivable ethnic influences in your work, and if so, how are they manifest?

Tough question, and without a doubt the answer is yes, but in today’s culture of ‘ethno-fetishisation’ certain aspects could be way over-rated. My father has always pursued martial arts and their associated approaches and disciplines. For example, meditation and notions of ‘chi’ (life force) have been part of my environment since childhood, however they manifest in a very understated and often commonplace manner. Being labelled as Asian carries a lot of baggage that is extraneous to my work. At the moment I’m in a process of transition between cities and a new name. I am changing my first name from Poonkhin to George, my maternal grandfather’s name (laughs)…which is paradoxical in today’s climate of ethnic reclamation. The exoticism can be an impediment to transparent communication when people focus on the messenger rather than the message.

This a pragmatic thing: I call up lots of people in hardware and hi-fi shops, and I’d rather avoid spending 10 minutes spelling my name, explaining how to pronounce it, where it’s from, and where my father’s family (never my mother’s family) is from. Being so linked to the notion of identity, my position on ethnicity is ambivalent and will continue to evolve. I think identity politics were a real issue in the 80s and 90s, and I just want to get on with making things happen rather than constantly being required to describe my position.

Okay, so George, how would you describe your work?

Primarily aural, with an emphasis on developing a sense of presence through atmosphere and spatial awareness. The focus is on aspects of space rather than object. It’s like trying to create a bridge that connects the installation site with the reality of the sound, much like the manner in which cinema establishes a sense of place/character/mood. The works are essentially concerned with various experiences of solitude, and take advantage of the implied solitude of the gallery context. A frequent response from listeners is the observation that the soundscape appears as an analogue for their own internal dialogue, and as such the works deal with the crossover between private and public spaces. They trace the meandering line of the lucid dream, with sounds drifting and emerging/merging. Quiet pulsing sounds, slow undulations and enharmonic drones challenge the listener’s perception, asking whether it is their shifting attention/perception or the work that is generating the ambiguity. I use silence as a dramatic ingredient, exploiting listening habits accustomed to conventional notions of music or an event. It is part of the subject/ground relationship, where the listener waits for something to happen in a conventional musical sense, and not hearing it, the ears become hungry. At this point the listener either decides nothing is happening, or in the heightened awareness driven by expectation they start to enter the work.

What inspires you to create?

Because I have to…(laughs)…no really that’s a very hard question. There are places I just have to be, and making these visual and sound environments is a means of getting there; I am drawn to these places. Each time I revisit them the space unfolds, and there are more corners to turn.

So is it fair to say that it’s not actually the space of first encounter you are trying to evoke, but rather a refraction of the real world seen from an internal space?

Yes. In a way I am trying to provide a portal to a space that was inspired by first hand experience. I start with the raw material, then I tweak it, watching how things change and transform. It becomes a journey where I follow the effects and transformations until the work arrives at a particular sense of place that feels complete. It’s a bit like meandering through the terrain, and reaching certain points along the way where, I might say, I can hang there for a while. Completeness really is a flexible notion in light of contemporary music/remix culture and there is no longer that concrete sense of finality and authorship…(laughs again)…I’d love to see visual artists remixing each other’s work.

In previous conversations you’ve mentioned duration as a key element of your work. Can you describe how it functions?

When you are with a particular piece of sound material for long enough, say between 10 and 30 mins, it will begin to sustain itself well after the actual physical sound has ceased (that’s one of the challenges in an installation context—getting the audience to stay!). It continues on in your head, and in the way you hear your immediate environment…you walk outside and the sound is still ringing in your ears…you actually perceive all the nuances of the material, but now it’s constructed from a combination of your own memory and the noise of your environment. Maybe this has a lot to do with the urban/industrial environment, all those fans and combustion engines, creating this rich blanket of noise that we can build sounds from. Actually I’ve been driven to total distraction sometimes, working in my studio late at night, building these extremely quiet situations and then realising that all the cooling fans inside my equipment are probably making more noise and complex resonances than my own recordings.

Collaborations form a significant component of your recent output. What do you gain from that working dynamic?

The key to a successful collaboration is a sense of mutual and shared intimacy with the material at hand. The best collaborations I have been involved with have a strong rapport as their foundation. I’m genuinely fascinated by my collaborators’ work, and vice versa (I hope). There is such a dominant culture of ‘hot housing’ projects (especially in the performing arts) that it is great to get the opportunity to let projects evolve organically at their own pace. This is important because long term partnerships can nurture details and nuances that don’t get the chance to appear in fast track projects.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 37

© Martin Walch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

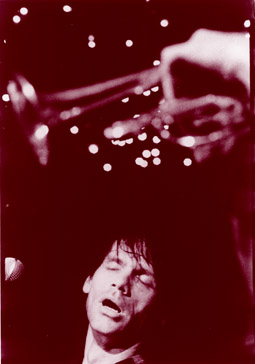

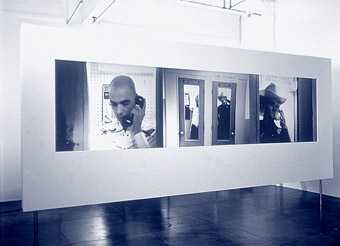

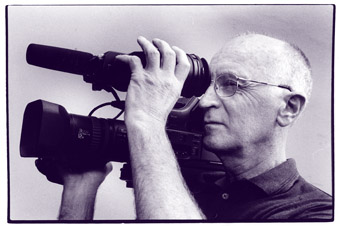

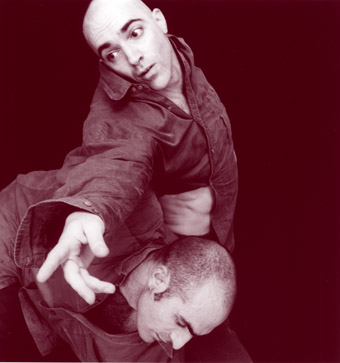

Pan Sonic (Newtown RSL)

photo netochka

Pan Sonic (Newtown RSL)

The Australian What Is Music? festival, directed by Oren Ambarchi and Robbie Avenaim, has become a regular outlet for new and experimental music since it began in 1994 (see RT 35, p24). This year’s event was the biggest and most well attended festival so far and can be seen as a coming of age, attracting a huge audience and an impressive line up of both local and international performers.

From the first night it was clear that there is an audience for such a festival. Last year was let down by an appalling venue in Kings Cross which caused many to stay away. This time the festival moved around; in Sydney at Imperial Slacks gallery, Harbourside Brasserie, Chauvel Cinema and Newtown RSL; in Melbourne at an array of venues including Punters Club, Revolver, Rechabite Hall and numerous pubs. The events spanned 6 nights in Sydney and 11 in Melbourne. The audience in Sydney was impressive, from 200 on the first night to over 500 on the last. The sheer size of the festival was like nothing ever seen in this part of the world for experimental, and predominantly Australian, performers.

The opening night saw well-known local Pimmon (who played a beautiful and well received solo set) paired with Hecker, the German laptop-er from the Mego label. Their sounds bounced around the gallery veering towards the grating and complex sounds that the Austrian label Mego is known for. Other highlights included Dworzec from Melbourne who played an incredibly fragile set, the audio hanging by a thread. Their sound, produced by guitar/electronics/synthesiser/accordion, felt like it could easily slip into lost noodlings or, as is the case here, hold a captivated audience on the edge of their seats. The final set by Minit brought a long evening to a wonderful come down, as their fine electronic sounds played out through electronics and a harmonium. The harmonium gave texture and Torben Tilly added an interesting visual aspect, sitting at the keyboard, dancing along to the beats that briefly appeared. The opening evening saw the electronic end of the contemporary experimental music spectrum, a definite aesthetic emerging as these artists seem to work closely with what can only be described as beauty, juxtaposed with a smattering of harsh noise to wake the dreaming head.

The second night showed off the other end of the spectrum, that of old-school improv. We heard Cor Fuhler (Netherlands) play prepared piano, Tony Buck with a drum solo, Loop Orchestra with tape loops, the sax/laptop combo of Max Nagel and Josef Novotny (Austria), and a computer piece by Julian Knowles, an audio work played to a slow-mo video of a long drive in the rain. The last performance, an interesting listen from the grouping of Tony Buck, Chris Abrahams (both from The Necks) and Jon Rose. Rose yet again felt the need to have a go at computer generated music, stating that his violin was a personal computer. His position is absurd and shows a strange sort of bitterness, no better than the crazy idea that one instrument is better than another.

The third night was held at the Chauvel where Farmers Manual (Vienna) played a 2 hour set of sound and video. Farmers Manual ask the audience to literally change their expectations of what music is and how they approach a performance, both in the sense of perception and entertainment. The work was created in real time through a network of data flows that utilised a vast array of data and information, much of which was never intended for music, let alone sound. The results are a long process that ebbs and flows from what sounds simply like noise through to a highly developed and structured audio output. The set ended on a high of strobing visuals and loud bass driven audio which left the audience in near shock. In Melbourne they played to a packed club but the basic, although shortened, outcome was very similar.

Makigami Koichi (Japan) was the biggest surprise of the festival for many. In performance he used a startling array of vocal techniques, veering from khoomei (throat-singing) to mock opera to Jews harp. The style was cut-and-paste with Koichi juxtaposing funny sounds with perplexing tones, theatre and dance. During his performance in Sydney, the audience was in fits of laughter, cheering at the end of each piece and demanding an encore. This style is not new to free improvisation; the difference here was the reaction from the audience, not usual for improvisation. In Melbourne the audience treated the work with awe-struck respect and in return were treated to a number of extended khoomei and Jews-harp pieces.

The final Sydney night at the RSL in Newtown was packed, at least 500 people through the door, for what turned out to be much removed from easy listening. This was by far the loudest evening of the Sydney leg of the festival. Smallcock and Nasenbluten played at volume and even the DJ packed a punch. The key performance was Pan Sonic (Finland) who stood behind their instruments, looking very blank, as they blasted out analogue bass from their ancient equipment. Pan Sonic audio is full to the point where it really hurts and many ears had fingers pushed firmly into them. The band have a long history in minimal electronic music which often borders on dance. Their current set gives up much of their experimental history for an easier to cope with 4/4 basis.

We can only hope that next year’s What is Music? festival continues to grow and open the vast range of experimental music to a quickly developing audience.

What is Music? 2001, Sydney, February 18-23; Melbourne, February 25-March 7; www.whatismusic.com

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 39

© Caleb K; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Few contemporary music concerts today seem distinctly contemporary without reference to technology. Even fewer concerts present both local technological prowess and creativity in such balance with traditional instrumental performance as did AUTONOMIC. In addition to a refined sensibility towards both practices, there was a certain synergy among the works compelling us to believe in the progress of music and the appreciation of those valued attributes of virtuosity and historical knowledge. All of this unfolding in the kitsch industrial space of Melbourne’s Public Office.

AUTONOMIC sat squarely in the arena of a contemporary music presentation. Although the relaxed clubby atmosphere had people enough to populate all the comfy chairs, a larger audience might have raised the dynamic further and with some scheduling adjustments, tightened the overall impact of the music. But Melita White’s program was both subtle and challenging.

Ross Bencina’s Dreamscape Resonances opened the concert with live computer-based sounds diffused through an 8 channel ambisonic surround sound system assisted by sound engineer, Steve Adam. Bencina developed the system on which he both composed and presented his music. Its complexity and sophistication spoke of the creative talent that Melbourne fosters and, perhaps, takes for granted. Each of the 5 works displayed a number of stylistic influences including ambient, electroacoustic and world musics.

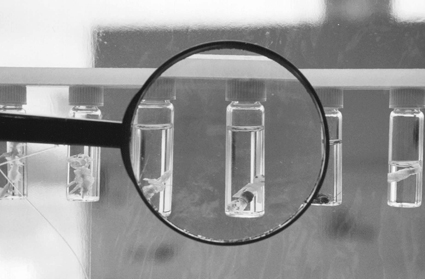

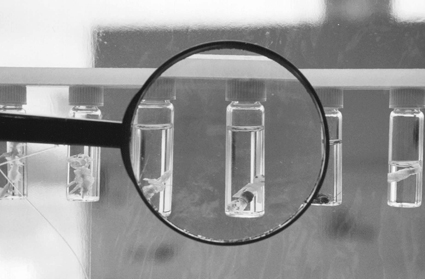

Immediately contrasting the electronic and sample base works, Melita White’s hydra threads addressed the instrumental and overtly live nature of music. Five water filled glass jars and a tenor saxophone, played by Keith Thorman Hunter and Tim O’Dwyer respectively, continued the sonic delicacy of the electronic works but added what was to be an increasingly visceral edge. The work, derived from a hymn, unfolded in the chiming jars and the melodic assertiveness of the saxophone.

The one + one—live improvisation again found Keith Thorman Hunter on percussion, but this time paired with Melanie Chillianis on flute, in a virtuoso display of extended flute techniques and a tableaux of percussive manoeuvres. Tentative private explorations gave way to attentive imitation. The resulting improvisation resolved fortuitously on the impromptu sound of a distant train horn.

ChronoDemonicCycling, an improvisation with Newton Armstrong on sensor driven computer synthesis and Tim O’Dwyer on saxophone, immediately cranked the energy level. From the start the sound was intense and unrelenting. O’Dwyer’s extensive repertoire of sax sounds was often indistinguishable from the electronic sounds which were the product of Armstrong’s use of gestural controllers to configure the synthesis engine.

Alexander Waterman’s short and intriguing Grammophonology, based on processed gramophone record samples, set the mood for the final solo work, sige, by Tim O’Dwyer. For bass saxophone and pre-recorded sound, sige was challenging with the O’Dwyer style again unleashed with some restriction of movement imposed by the mounted sax. Nuanced techniques of key sounds and resonant aspirations through the instrument, occasionally lost amid the complex tape sounds, exemplified O’Dwyer’s skill and understanding of the saxophone family.

* * * *

A visually intriguing collection of percussion instruments (that could well have been an installation of late 20th century percussionist tools) was encountered in the Melbourne Museum between the Bunjilaka Aboriginal Centre and the Kalaya Meeting Place. The wide curved walkway quickly filled with the cognoscenti and the curious, who witnessed a lively and often humorous performance by percussionist Vanessa Tomlinson, as part of an ongoing series of Sunday recitals in the new museum.

Given the number of children in the audience, the opening work for amplified, stroked and massaged balloons spoke directly to the idea of music from simple things. Dear Judy was as much a theatrical performance upon the balloons as when Tomlinson resorted to silent gestures upon her own body. For every child there, the work legitimated the idea of environmental and sonic self-exploration.

Warren Burt’s Beat Generation in the California Coastal Ranges saw Tomlinson shift slightly towards a more sophisticated performance practice. Deceptively simple on the surface, the work’s recorded sine tones and vibraphone sound had, at certain times, an interesting cumulative effect, highlighting the challenging nature of the work. Listening for the interference or beat patterns that emerged between the notes played on the vibraphone and the shifting sine tones was certainly the attraction. This ‘third’ sonic behaviour encouraged attention to the sound and an anticipation of the onset of the beating characteristic.

Bone Alphabet raised the virtuoso level still further by introducing a greater range of instruments and a visually complex performance procedure. Had Brian Ferneyhough’s work been surreptitiously placed at this point? While certainly challenging, its complexity seemed subordinate to the spectacle of the performance. Listeners unfamiliar with Ferneyhough’s repertoire and style could easily absorb the spectacle as another dimension to the possibilities that overflowed from the array of instruments before them.

Finally, Anthony Pateras’ Mutant Theatre was clearly anticipated. Apart from being a ‘First Performance’, the children and many adults seemed eager to witness the outcome of the fall of colourful dominoes that would intermittently trigger mousetraps with balloons attached. As it happened, the fun part was over with a speed and subtlety probably not anticipated but the greater part of the composition held moments, in both the music and instrumentation, of equal fascination. Smashing light bulbs, sprinklings of marbles across instruments, a roaring gong and sounds from toys and cheap electronic instruments created a tour de force which closed the concert to acclaim.

AUTONOMIC, Auricle New Music Ensemble, Public Office, West Melbourne, February 23: Virtuosic Visions, Vanessa Tomlinson, percussion, Clocked Out Productions, Melbourne Museum, March 4

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 40

© Alistair Riddell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

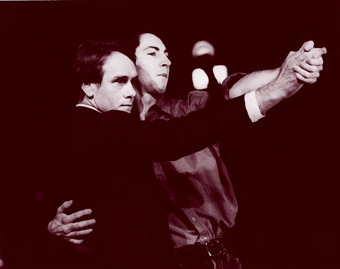

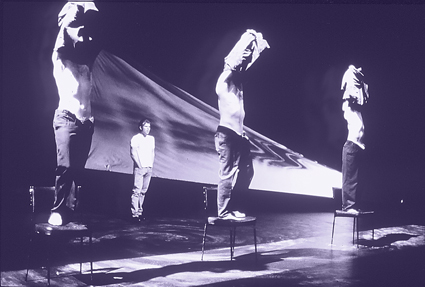

Leeanna Walsman & Nathan Page, La Dispute

photo Tracey Shramm

Leeanna Walsman & Nathan Page, La Dispute

Editor’s introduction

Just as the arguments prompted by Richard Wherrett’s National Performance Conference speech seemed to be thinning out, playwright Louis Nowra added another perspective to Wherrett’s “crisis” in his essay “The director’s cut” (Spectrum, Sydney Morning Herald, Feb 3).

While Wherrett sets out to evoke a malaise and suggest tough solutions, Nowra is more analytic. Like Wherrett he sees Australian “theatre as drifting without much of a purpose”, but he offers more than an absence of humanist vision and funding spread too thin as reasons for the condition. Nowra argues that a new generation of directors (who, like Wherrett’s targets, lack humility) do not engage with living playwrights, and that filmmaking draws other potential directors away from the stage (“the real reason for there being more women directors is not so much a deliberate policy, but the natural process of filling a vacuum left by young male directors”).

Yet again anti-humanist postmodernism—which has had nil effect on mainstream theatre in this country (save being railed at by David Williamson)—is the whipping boy. By tackling only the classics (the authors are dead and untroublesome), Nowra writes that “young directors are saying they are the authors of their productions.” Who are these young directors, what are the works they actually tackle, and, more to the point, if they are at fault, how many are there—enough to constitute a crisis? Hardly.

Of innovative directors, Barrie Kosky is the easiest target, directing theatre and opera classics since leaving behind his collaborative Gilgul Theatre Company venture. Who else then? Surely not Michael Kantor, a provocative director who has committed himself to a steady output of new Australian plays and music theatre works, nor Jenny Kemp who alternates directing her own works with classics (Marivaux for example for MTC), new works (Joanna Murray-Smith’s Nightfall) and collaborations with dancer Helen Herbertson. What about Benedict Andrews, Resident Director at the Sydney Theatre Company, the director Nowra uses as prime example of the problem? Nowra is curiously oblivious to Andrews’ association with playwright Beatrix Christian in the 2001 Sydney Theatre Company season on 2 projects—her new play, Old Masters, and a re-working of Chekhov’s Three Sisters (yes, a classic, but adapted by Andrews and Christian). It’s hard to think of key Australian directors who are not working with living playwrights.

Nowra blunders badly when he tries to portray young Indigenous directors as the good guys: “Interestingly, this is not a feature of emerging Aboriginal directors such as Wesley Enoch who, in shows such as 7 Stages of Grieving and The Sunshine Club, is determined to tell stories about his people by working with Australian writers.” In fact Enoch wrote both shows, the first with performer Deborah Mailman and the second on his own (the composer was John Rodgers). And what about his Black Medea for the STC and Grace for Kooemba Jdarra. Of course, he has directed plays by Nowra and Kevin Gilbert, but let’s not see Wesley Enoch as somehow different from his adventurous peers.

Once again, the problems facing Australian theatre are dealt with inadequately and misleadingly. Nowra admits admiration for Andrews’ directing, but bewails his lack of humility when producing a classic play and his alledged failure to work with living playwrights. Benedict Andrews replies. KG

******

Fidelity

I enjoyed Louis Nowra’s article “The Director’s Cut” because it steered the recent banter triggered by Richard Wherrett away from bitchier, subjective terrain into a discussion about ideas and values.

Louis also raised significant issues about the relationship between director and writer which I feel beg response. Given the article’s idealising of several established directors versus its anxiety about young directors, I feel compelled to offer an alternative point of view.

The theatre, it seems, is haunted by the dead. At the core of its practice is a fundamental tension between the present and the past, between the living and the dead, between the written and the read. This tension necessarily spills over into questions of authenticity, authority, and interpretation. The dead want to keep living, they keep coming back, to speak to us, but with whose voice?

The actor embodies this tension. Robert Menzies, a great Australian actor with a unique relationship to both classical European texts and new Australian writing, once remarked to me on the strangeness of the stage actors’ role. Where else in life could someone claim that at a certain time every night they could know exactly what they will be feeling at any given moment? For instance, that as Oedipus at approximately 10.25 each night for the run of the STC season last year, Robert would play a man driven to the limits of guilt and despair choosing to rip out his own eyes rather than see the light. And night after night, the actor will convince us, the audience, that we are witnessing this terrible and beautiful event for the first time. And indeed we are and we are not, at the same time. This is the doubling act of the theatre that Artaud wrote of, its shadowy presence.

Theatre is a kind of exorcism. Oedipus, like Hamlet, will not die. These characters keep coming back through new bodies, so new audiences can bear witness. Seneca’s re-telling of the primal myth was written around 500 years after Sophocles’ Oedipus trilogy. Around 2000 years later, Ted Hughes translated Seneca’s text and created a new version that contained the bloody language knots of his poetic genius and our century. When Barrie Kosky directed Hughes’/Seneca’s Oedipus for STC last year he also created a new text. I saw the production several times because I was attracted to its intelligence, rigour and the relentless nature of its poetry. By confining the action, to a small scaffold, Kosky created the equivalent of a filmic close-up, an x-ray into the hallucinations of Oedipus, the puppet show of his unconscious. The power of this production was built upon a love of the playwright’s language and an awareness that as one of the core myths of Western civilisation the Oedipus myth, like the Sphinx’s riddle, cannot be forever solved. It remains a knot to be worked over by the actor. So, nightly confined on a crude stage for 2 hours, Robert Menzies would begin again, raise his ghosts and civilisation’s plagues. It is finally only the actor who brings theatre into play, who makes any communion possible between his/her body onstage and our bodies in the audience. To quote Ted Hughes, “It has never been my illusion that the theatre should belong to the writer. The theatre belongs to the actor…”

I am interested in the meeting point between a written text and the living body of the actor. I am also interested in the impossible conversation that occurs when working on a ‘classic’ text. I love the process of taking words and ciphers on a page from another culture and epoch, and translating them over time into the bodies of the actors, into something living and current. I like this exchange across centuries, this archaeology into the languages and thought processes of civilisation, this interrogation of what it means to be human. It seems to me that the theatre is precisely the place where these exchanges can still take place.

I am not interested in museum theatre or a received notion of approaching a given writer. Whether approaching a text that is 2000 years old or 2 days old, as director I strive to discover the text for the first time, to x-ray its insides and release its mysteries and demons. I try to explore (with and through the text) ideas about what it feels like to be alive, to ask questions about power, sexuality, death, love and other wonders. I search for very personal connections between my self and the work. Otherwise it is a dead thing.

So I was a little disturbed to read Louis Nowra’s recent statement that “many young directors want to tackle a classical text because it is easy to stamp their authority and ego on a canon piece by dismantling it and interpreting it anew.” This seems to me to be an alarmingly cynical view of the motivation behind the work of young artists and a shallow understanding of the reasons why a director might choose to engage with a classical text. Theatre is not an easy place. It demands intellectual rigour, emotional nakedness, and febrile imagination. As a director, I work on both contemporary texts and classical texts. I work with living writers and dead ones. I do not breathe some sigh of relief as Louis Nowra might imagine when working on a classical text as if I were suddenly free to dance on the playwright’s grave. Each project is demanding and all consuming and I enter it with questions and fantasies I want to explore with the community of people I work with and the audience who will watch our work.

There are reasons why classical texts keep coming back and directors and ensembles keep exploring them. When I think of plays I consider to be great classics, I love them because they are bigger than me. They have come through time like shards in an archaeological dig, full of secret lives, messages, and codes. This is why a director can return to Hamlet or King Lear several times during his/her life. The material is rich, dense and elusive enough to provide new challenges and glimpses over time. The renegade Italian director Romeo Castelluci speaks of the kind of awe an ancient text (in this case The Oresteia) inspires: “I wanted…a text before which I would have to bow, absorbing its mystery, and shaking from ‘contact’…”

I fear Louis Nowra is subscribing to a rather cheap, worn cliche of Director’s Theatre when he proposes that certain directors are concerned only with directorial authorship rather than the authority of the text. This notion is in danger of setting up a hierarchical schema that says Playwright sacrosanct, Director servant. I am not sure that this rule leads to the most exciting theatre. It seems to place imagined constructs of fidelity ahead of the desire to make engaging theatre. Hinting at a more open and braver idea of theatre-making, playwright Beatrix Christian said recently that “a play-script isn’t literature, it’s one limb of that deeply complex, mysterious and volatile organism called theatre.”

Translating any text to the stage is a process of interpretation and therefore a political act. When we represent ourselves onstage we address our assumptions about who we are and what we value. In rehearsal we work through the language and ideas of the playwright and transform words on a page into actions and emotions to be felt by the actors and the audience. Unlike an essay, novel, poem, or the frozen time of film, theatre is made only through living bodies in real time. The written language forms a skeleton of ideas and emotions which are brought to life (or made into the act of theatre) by the physical utterance of the actor, the spatial constructions of director and designers, and the reception of audience.

When I think of productions of ‘classics’ which have thrilled me, it has been clear that the director has worked with the material to release its life for a contemporary audience—the radical deconstructions of the Wooster Group towards O’Neill and Chekhov, Heiner Müller’s production of Brecht’s Der Aufhaltsame Aufsteig des Arturo Ui, Castelluci’s visceral retelling of Giulio Cesare, Peter Sellars’ contemporary political takes on Sophocles and Mozart, Stephen Daldry’s An Inspector Calls, Eimuntas Nekrosius’ recent Hamlet, or Kosky’s production of Mourning Becomes Electra. They each contain a tension between the written language and the theatrical language. They follow the text but reveal unexpected readings, hidden corners, or blow away received assumptions to reveal the writing afresh. This I consider to be faithful to the writer and the play. It is an imaginative engagement and trust which I would wish for from any writer (living or dead) who believed in the continued life of the theatre.

Louis singled my production of La Dispute by Pierre Cartlet de Marivaux as being indicative of “a young director establishing his authority over the writer.” While on the one hand calling the production “fascinating and riveting”, he also argues that it was a “perverse distortion of the original text” which would have left anyone who didn’t know Marivaux with a “wrong” impression of his work. While I find it lamentable that our theatre culture has not permitted us to have seen other comparable productions of Marivaux’s plays, I do not feel it is my responsibility as a contemporary theatre director to create a museum version of his work based on a finite, Platonic notion of how his work is supposed to be played. I think the Comedie Francais are probably already doing a good enough job of that.

I do believe however that my production was faithful to this particular (and peculiar) Marivaux play. I also cannot divorce myself from the history of my own times in making the play. The production was created with an acknowledgment of the horrors of the 20th century—the experiments of Nazi concentration camps, the orphanages of Ceaucescu’s Romania, and the state sponsored stealing of generations of Indigenous children. It shifted the question about who is more treacherous in love, male or female, into a contemporary anxiety about the nature or artificiality of sexuality, the processes of language and subjectivity, and our ability to accept or deny difference. I did not impose these things upon the play. They were written into the 19 short scenes by Marivaux in 1744. I believe that the supposed dispute about fidelity of the play’s title (which remains unresolved and ambivalent) was not Marivaux’s primary subject matter but a smoke screen, a gilded frame in his mirror box.

La Dispute is a problematic play for Louis to single out in a discussion about textual fidelity. It was a notorious failure with Parisian audiences at its 1744 premiere at the Comedie Francais. It played for a single night and was confined to the dustbin of history and academia until Patrice Chereau’s legendary 3 and a half hour production in 1973. The play has since found a modern audience 250 years since its failed premiere.

La Dispute is what Richard Wherrett might term a ‘minor classic’, but it comes as a perverse and fantastical document from the Enlightenment which has the ability to speak across and of history, to provoke questions about the history of Western subjectivity, and engage with Sydney audiences in 2000.

Louis makes another very upsetting statement in his article. He says, “In fact, theatre itself is not inspiring young directors.” He claims that most would prefer to direct film because it is an “exciting, sexy” medium, and implies that those working in theatre are simply filling a vacuum left by an exodus of (predominantly male??) directors to film.

Theatre and cinema are different mediums. One is certainly not sexier than the other. As a ‘young director’, I choose to work in the theatre. I am not killing time until a film shoot. I love working with actors and writers in the theatre. I am in love with its particular imaginative and technical demands. I like the time to play and question that theatre gives me, without the need for an extensive and expensive technical apparatus. I like the privacy of rehearsal and I like sitting in the audience watching live actors. I love the impermanence of theatre. It is live. It disappears. It can only be held in the memory.

PS This is a worry. I just did a spell check and my laptop did not recognise the word MARIVAUX. It suggested MIRAMAX.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 23

© Benedict Andrews; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

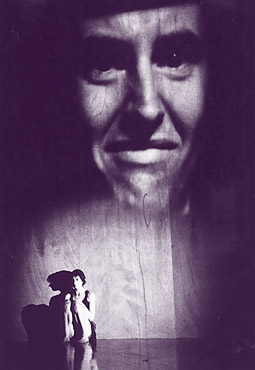

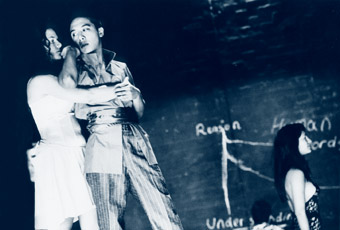

The Marrugeku Company, Crying Baby

photo John Green

The Marrugeku Company, Crying Baby

I’m a sucker for (bad) puns at the best of times but given the recent history of the Perth International Arts festival (PIAF), they’re downright irresistible. Either that or Director Sean Doran shows an alarming prescience. ‘All washed up’ seems to capture the fairly catastrophic outcomes of last year’s PIAF. Themed ‘water’, it was a festival that began with a deluge that drowned out the opening night Philip Glass concert and ended with a massive financial dunking. Aptly enough, this year’s festival, carried the theme ‘earth’ and given the limitations of the budget, programming was indeed, much more ‘down to earth.’ The mind boggles at the possible outcomes of the ‘fire’ and ‘air’ festivals yet to come!

Despite the tight budget, there were some strikingly positive outcomes for local artists, companies and organisations. In the visual arts, while the budget for exhibitions remained more or less consistent with that of previous years, the appointment of a Visual Arts Manager, Sophie O’Brien, meant that this festival within a festival was infinitely more focused and substantial than previously. On the other hand, while this year’s theatre and dance program was a much more low key affair with far less emphasis on big ticket overseas acts than has historically been the case, it strongly featured local performing arts companies and projects. While most of them received zip financial contribution, the value and scale of the marketing and promotion offered through the festival paid huge dividends in terms of excellent box-office returns for the participating companies.

In terms of content, you’d be hard pressed to find a connecting theme. It was definitely a ‘something for everyone’, fiscally responsible, kind of affair. There was a bit of emphasis on works from South Africa (the Baxter Theatre Company, Ellis & Bheki) and there was a certain pleasant irony in that the headlining Australian theatre works were both strongly Aboriginal in focus (Marrugeku and Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre Company). Beyond which you could take in the really big one, the Merce Cunningham Dance Theatre, and smaller projects such as the charming and virtuosic Cirque Éloise from Canada, the slightly daggy (and derivative) but kind of interesting ‘popera’ Denis Cleveland from New York or the inevitable production from ‘ye olde merrie England’, A Servant to Two Masters, by the Young Vic and Royal Shakespeare Theatre Company. This year’s program was thankfully free of Irish drama.

Marrugeku’s Crying Baby was probably the highlight of my festival. This ongoing collaboration between members of Stalker Stilt Company, Perth-based Indigenous performers and the Oenpelli community in Arnhem Land remains the most artistically, conceptually, politically and socially ambitious work being made in Australia today. The issues are huge and directly impact upon the working process of the company (see RT#41) but the fragility, vulnerability, confusion and instability of that collaborative process is one of the most hopeful things I have witnessed in Australian theatre.

Ironically, Crying Baby was performed at The Quarry Amphitheatre, a favourite outdoor venue for those who prefer their theatre as a kind of benign backdrop to the pleasures of chilled white wine and a gourmet picnic hamper. It’s a beautiful site surrounded by bush, overlooking the lights of the city and Mark Howett’s lighting and Andrew Carter’s sparse set—suggestive of the weird sculptural forms of much of the flora in Arnhem Land—made for an extraordinary environment.

Crying Baby connects the story of an orphan boy neglected by his tribe and the retribution of Kunjikuime (a form of Rainbow Serpent). The performance extends this story visually, aurally and spatially, to encompass the experience of the children of the Stolen Generations, even drawing on that favourite trope of non-Indigenous Australia, the white child, lost in the bush. The story is told in ‘language’ and drawn in the sand by elder and storyman, Thompson Yulidjirri, and translated into English by composer and musician Matthew Fargher. It is elaborated through beautiful and poignant filmwork by Warwick Thornton (Katjet people, Central Australia) which juxtaposes images of a white child wandering aimlessly through grey green bush with archival footage of Aboriginal mission children. The live performers, often on stilts as Mimi spirits, appear and disappear, as do the extraordinarily compelling traditional dancers. Also interwoven is the post-contact story of Mr Watson, the first missionary in Arnhem Land, who removed the Kunwinjku people from their land Gapari (the Crying Baby site) to Goulburn Island.

For the most part, Crying Baby has a haunting, dream-like and evocative quality. It is extraordinarily moving and leaves you in no doubt that these people, stories, spirits, do inhabit and move across the land. The only difficulty I had with the work was a sense that, as Marrugeku, there are still (inevitably) moments of Stalker, which seem to pull the work back to a different place and time and create a kind of rupture. While the stilt-work is perfectly suited to representing the elongated Mimi spirits, the flying scenes, in which the sheer logistics of getting ‘crying baby’ hooked up and swinging around, seem clumsy and not worth the effort. However, this is quibbling. In the end, to quote director Rachael Swain, “this is an important piece of art communicating to a diverse audience in remote communities and urban festivals nationally and internationally.” It is also about reconciliation as more than a glib catchphrase, as a lived process inclusive of pain, listening, grief, moments of great beauty as well as loss and stories of country both pre and post-contact.

The experience of Crying Baby made other works dealing with the effects of colonisation, dislocation, loss and trauma rather more disappointing. Alice, directed by Sally Richardson for the Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre, was a really difficult show for me. I’d previously seen a showing of the work in development some 18 months earlier. As Alice Haines: One Night Stand, this much rawer version of her autobiography communicated directly and simply to the audience through straightforward storytelling, song and music. This festival version, however, with the addition of theatrical lighting and set (by the ubiquitous Mark Howett and Andrew Carter) looked like a bad 1970s pub act. Alice is known to many, as singer with the band Mixed Relations, and had this show focused more on her strengths as a singer it might have been a more substantial work. Alice’s stories of pain, loss and survival deserve to be heard but unless some serious critical analysis and dramaturgical rigour is brought to both the material and the process, it will not begin to achieve its potential.

Suip: The Fruit of the Vein by Baxter Theatre Company was extremely familiar to anyone who’s seen any theatre from South Africa over the past decade. Again, this is an important story of cultural shock, trauma and alcoholism. It is a community work in the sense that it was originally developed by young drama students at the University of Capetown keen to explore the legacy of previous generations apparently irreversibly damaged by the effects of colonisation and alcohol. They spent a month on the streets living with, interviewing and learning from their elders. The result is TIE (theatre in education) style theatre with a strong message and generally solid performances. With the exception of the outstanding onstage percussionist, Nkululeko Mzwakhe Hlatshwayo, and the young silent ‘boy’ beautifully performed by Nicol Sheraton, its in your face style drove me mad. As with Alice, however, audiences responded fairly rapturously.

It was great to catch up with 3 parts of a 4 part program, prag/port/perth, curated for the WA Fringe Festival by Berlin-based, Australian dance artist Paul Gazzola. Gazzola’s work has a strong orientation to live art (as opposed to dance per se) and this program, encompassing dance, video, installation and performance by artists from the Czech Republic, Portugal and Perth, reflected those interests. Unfortunately I missed his reprise of the Yoko Ono performance work Cut Piece. I did, however, manage to see Claudia, the video installation by Portugese artist Noe Sendas, a re-working of aspects of Fellini’s 8 1/2, as well as Venus with the Rubics Cube by Czech choreographer Kristyna Lhotakova and musician Ladislav Souk. A duet between double bass and dancer, this deceptively simple and idiosyncratic work dealing with anorexia and the ‘image of the perfect woman’ exploited a touching physical gawkiness. The final piece in the program was Calculating Hedonism: Performance stories from sober and temperate bodies, a collaborative work by Perth-based artists Felicity Bott (dancer), Bec Dean (singer/video artist), David Fussell (performer) and Paul Wakelam (architect, designer & LFX). In some ways, this work reminded me of New Yorker Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theatre, particularly in its use of language to describe shifting psychological states, odd visual/physical juxtapositions and, of course, Foreman’s use of string to articulate the theatrical space. Similarly, Wakelam’s precise mapping of the performance area in coloured tape created an animate sense of space. While Calculating Hedonism, which dealt with the “calculating approach that contemporary society takes to its social relationships, their bodies and leisure time”, would have benefited from some judicious editing, it was great to see performers really playing with form. I was happy to be there.

–

Crying Baby, The Marrugeku Company, storyman Thompson Yulidjirri, director/writer Rachael Swain, choreographer Raymond Blanco, composer Matthew Fargher; collaborator/performers Dalisa Pigram, Sofia Gibson, Trevor Jamieson, Katia Molino, Simon Peart, Tanya Mead, Eddie Nailibidj, Rexie Barmaja Wood, Harry Thomson; The Quarry Amphitheatre, January 31-February 4; Alice, Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre, creator/performer Alice Haines, director Sally Richardson, Subiaco Theatre Company, Jan 31-Feb 17; Suip: The Fruit of the Vein, Baxter Theatre Company, writers Heinrich Reisenhofer & Oscar Petersen, director/choreographer Heinrich Reisenhofer, Octagon Theatre, UWA, Feb 7-11; Prag/Port/ Pert, 4 part program for the WA Fringe Festival, Rechabites Hall, Feb 7-14.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 24

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

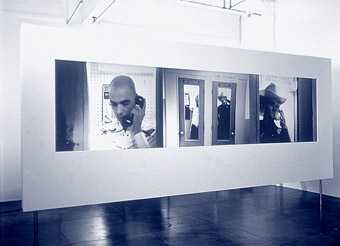

Danny Diesendorf, Dead Caucasians

‘pling

Danny Diesendorf, Dead Caucasians

Canberra is a small town and I approached this play with a little trepidation—most of the cast and crew are close friends, and negative comments on a work can often be far more trouble than they’re worth. Wearing my flame-retardant underwear I made my way into the packed and somewhat stuffy Courtyard Studio at the Canberra Theatre Centre. Social Division, which presented this play, is a typical flag of convenience that badges local collectives in the absence of a properly funded professional theatre company in Canberra to foster such work.

Theatre and performance in Canberra have been in limbo since the demise of the mighty Splinters. Subsequently we’ve had not much more than an endless array of pretty ordinary plays, albeit very well produced and performed by an extremely professional theatrical community, interspersed with Bell Shakespeare’s overwrought extravaganzas and the occasional gem from expatriate installation/performance makers, Odd Productions.

A large part of the problem is the lack of writers. Canberra really only boasts 2 shining young talents in Jonathan Lees and Mary Rachel Brown, and their output is sporadic; of course it’s much harder for theatre writers to make a crust from their art than actors. So Canberra is lucky to count Christos Tsiolkas as an honorary local by virtue of 18 months spent here. This has resulted in an ongoing partnership with actor/director David Branson and the bond has already borne fruit in the form of the plays Viewing Blue Poles and Elektra AD.

It is a privilege to watch the development of a writer of genuine stature in this country and Dead Caucasians must be seen as a watershed in Tsiolkas’ career. Elektra was controversial here, and I found the technique of pummelling his message into your skull by yelling and swearing and pointing spotlights in the audience’s face tiresome. Branson as Director could share the blame, but I had the same trouble with the novel The Jesus Man—the descent of the protagonist into the abyss simply wore me out and I lost interest.

Dead Caucasians works because Tsiolkas now has sufficient wisdom to be compassionate towards all his characters. There are no good guys and bad guys, just a diverse and curiously interconnected group of ordinary people struggling to cope in the Australia of 2001. Some of them are driven to perform terrible acts of violence but shock is not (as is all too often the case) the obsession of the writer. The violence demonstrates clearly the inexorable and horrific consequences of the policies of John Howard’s government, at the same time as stirring the sense of the deep human bonds between us all. And it’s beautifully structured: after an initial shock, the tempo drops, and when the violence comes again later the device is perfectly timed.

Each of the cast was required to play several characters. The actors’ job was made easier by simple variations in costume—a jacket on or off, a skirt unzipped to show some leg—though a number of people I spoke to found this unclear. This actually led me to the conclusion that the author was deliberately inviting comparison between the characters each actor played. For example, Chrissie Shaw played a 70-year old Holocaust survivor, a 60 year-old bigot and a 40-year old white trash mother who keeps some bad company, and I found myself meditating on how narrow the divides really are.

Under the direction of Roland Manderson, the cast and crew were impeccable. Branson, Shaw and Danny Diesendorf stood out and were ably supported by Anna Voronoff and Rebecca Rutter. The costumes by Matthew Aberline, though untypically muted grey, were delectable. Pip Branson and Nik Craft performed a gorgeous, limpid score and I hope I will be forgiven if I describe it as Ry Cooder-meets-My Bloody Valentine.

This is a work of substance and deserves to be staged around the country. It is one of few recent plays which leaves me with a clear sense of it being good art, good craft, with a clear message. It demonstrates what can be achieved through a reasonably extended development time with an ensemble. I am left with a delicious sense of anticipation for future works, and have been bashing Branson’s ear to get Christos Tsiolkas together with Constantine Koukias in Hobart. Combined with Koukias’ grand visions we could be in for some real treats. Here’s to work with the guts for the long haul.

Dead Caucasians, writer Christos Tsiolkas, director Roland Manderson, The Courtyard Studio, Canberra Theatre Centre, Jan 25-Feb 3

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 28

© Gavin Findlay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Margaret Trail

photo Peter Rosetzsky

Margaret Trail

Margaret Trail is an adept performer of sounds. She can manipulate meanings, extracting sense from nonsense and vice-versa. Trail evokes the memory of sense. Sentences seem sensible, or at least they feel like they might have been once. Sounds are uttered, spluttered, stuttered. These too were once sensible sounds. They would have quietly sat between words minding their own business. Trail hovers above meaning, diving down into the abyss, rummaging amongst the sounds of sense.

K-ting! opens with a diatribe about the werewolf, magic words, signs, symptoms. An anachronistic story is offered against a dark background, the performer dressed in black. The setting for this performance might appear occult but it also looks like stand-up comedy—a single person speaking non-stop under a spotlight. It is not at all clear whether these words are funny or scary. If they seem funny, it’s not because of their content. It’s because of their playfulness, their surreal juxtapositions. And if they seem scary, it’s not because anyone is actually scared.

There are 3 quasi-acts to this show, parts of which have been shown before. Some consist of simply spoken narrative such as the werewolf section. Other parts embody those funny sounds that don’t make sense but that accompany sense-making. Here, Trail works with these sounds, taking away their everyday accompaniments to displace their normality. A laugh about an absent joke repeatedly punctuates a story.

Trail also uses technological means to either replay recorded sounds—such as a dog howling or glass shattering—or to play sounds to herself in the headphones which she then responds to. This latter mode gave the audience only half the story, allowing us to witness the oddness of a one-person dialogue. It also made palpable the fact that speech incorporates a mixture of references involving presence and absence. We hear a tale recounted of Trail meeting someone in a bar who describes himself as a fireman. What is a fireman? Someone who likes to smash things. Trail says she herself likes to smash things…sounds of smashing glass. She then calls herself supermodel Margaret. Someone else is fireman Sam; she can be supermodel Margaret.

What is it to describe yourself to someone in a manner beyond verification? Of course, we see Trail. We don’t see the conversation in the bar, we hear about it. It is repeated for us as stories are. Perhaps we continually make references in our speaking to that which is beyond verification. In the 1950s, the logical positivist philosophers claimed that if something could not be found to be either true or false, it did not make sense. After K-ting! one might be led to wonder how much sense is permeated by unsense (nonsense?). Speech is more complex, and sense more fluid than one might suppose.

After K-ting!, I emerged sense-dizzy, experiencing the most ordinary remarks as odd. Trail’s work isn’t a poetry of sound. It is a disorientation of sense. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with language, it’s just that it isn’t as normal as it seems. Madness lurks in the most innocuous of phrases.

K-ting! Extended play, writer/performer/ recorder Margaret Trail, lighting/technical production Dori Dragon, La Mama, Melbourne, Feb 28-March 11

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 28

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ros Warby, Eve

photo Jeff Busby

Ros Warby, Eve

I have always known Ros Warby to be a versatile and popular dancer. She is as able to sustain the fine detail of choreographic composition as she is to create complex beauty within the moment of improvisational practice, a modality that has captured her interest for some years now.

Solos merely underlines Warby’s ability to move in very different ways, for it consists of 3 pieces by quite divergent choreographers. Eve is Warby’s own work, Living with Surfaces is by Lucy Guerin and Fire is a recent Deborah Hay composition. The juxtaposition of these works allowed for a comparative reverie on the varieties of choreographic concern. The fact that one dancer performed all 3 works provided a constancy which unexpectedly heightened the differences between the works of each choreographer.

Eve was presented first, an appropriate choice since here dancer and choreographer are one. Ros’ entry into the space felt like an act of naming, a presentation of the corporeal and personal energy behind this project. This was enhanced by the fact that the piece is about woman, perhaps one, perhaps many. The set consisted of curved wooden surfaces upon which Margie Medlin cleverly and variously projected filmed images of Ros in movement. The images were always partial—a glimpse of hips shimmying, an arm, a torso—forming a dialogue with the live movement. This made the work feel less of a solo.

The dancer’s own attention was directed towards particular nuances of the body, tippy-toes, stuttered walks, indulgent spirals. Quite specific gestural moments were created, as if the body speaks but in another tongue. There is a quality in Ros Warby’s movement that is quite her own: an elfin quickness, the ability to change tempo in the blink of the eye, without the obvious preparation say of ballet’s pirouette. The intentionality of each action is manifest in the moment and not a second before. Naturally, Eve exhibited this quality more than the other 2 pieces, though Deborah Hay’s Fire did provide for moments of disjunctive and unexpected change.

In comparison with the fullness of subjectivity presented through Eve, I was quite shocked by the stark evacuation of the self in Lucy Guerin’s Living with Surfaces. A bold green wall was placed centre stage, the dancer emerging in pillar box red tulle and satin. From pointed fingers touching the wall, through the precise play of joints, and the placement of weight, it became clear that Guerin is interested in what a body can do. The body in movement leads this dance rather than some humanist conception of spirit or content. Guerin is not alone in this manner of composition, though she does offer it a very fine and precise articulation. Clearly this is what attracts Warby to the work, the absolute commitment to motion, and an informed detail in movement that is ultimately identifiable as Guerin’s own kinaesthetic. This is the point at which the human re-enters the frame, for Lucy Guerin contributes movement that emerges from her own particular and distinctive body.

Fire again instituted a complete change in what is taken to constitute choreography. Some people understand Deborah Hay’s work in improvisational terms but she rightly rejects this. Each moment in Fire is precisely determined in that the performer has to satisfy certain requirements. There is a choreographic script. However, there is no predetermination as to what shape will satisfy the choreographic instruction. This can only be found in each moment of performance. To this extent, Russell Dumas is right to suggest that all performance is improvisational in that movement has to be found in the moment. But improvisation, as a modality, adds another layer of variability that is not evident in Hay’s work. Rather, Warby has to follow a series of instructions, which she adheres to with total commitment eg “move across the stage dancing fire, interrupting to speak questions to the audience such as: who are you?”

A weird piece emerges, out of real time, yet tapping into something quite interior to the performer. An interiority that is quite distinct from the surfaces of Guerin’s work, and different again from the emotional and personal interiority of Eve. Although Warby has to work with her subjectivity in managing the dance of Fire, there is an impersonal tenor to it that takes over. What you see is a person expending their entire focus in the satisfaction of an eccentric inspiration.

Although it does represent a feast of difference, Solos is also a sign of Ros Warby’s own concerns, her sustained thinking and rethinking of what constitutes dance and performance, and how to work. Partly a homage to Guerin and Hay, perhaps it is also anticipating things to come. For that we can only wait. Meantime, we savour the moment.

–

Ros Warby, Solos: Eve, choreographer Ros Warby, composition Helen Mountford, projection design Margie Medlin, cinematography Ben Speth; Living with Surfaces, choreographer Lucy Guerin, costume Mila Faranov, music Alva Noto, Stilluppsteypa, Foehn, & Crank; Fire, choreographer Deborah Hay; North Melbourne Town Hall, Melbourne, February 14-18

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 30

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sean Mununggur, diretor Stephen Johnson, Yolngu Boy

In the current climate there are lots of feature films being made from Indigenous stories by non-Indigenous filmmakers. Beyond the Rabbit Proof Fence by Phil Noyce is a good example. Others are in the pipeline with ex-pat directors returning home from Hollywood. Meanwhile, Indigenous filmmaker Ivan Sen has just started his first feature Beneath Clouds. Others like Rachel Perkins, Erica Glynn and Richard Frankland all have projects in development.

Yolngu Boy sits somewhere in between. A black story told by a white creative team supported by Indigenous associate producers. Much respect to the Yunupingu brothers in giving the filmmakers access to the communities and culture of Arnhem Land.

Yolngu Boy is a tale of instruction, almost a fable, which follows the story of 3 young lads who share the same totem: crocodile. The message is simple. If you follow your culture and stay strong then you’ll remain on track to becoming a man. If you stray off the path then you’ll be in trouble. At the beginning of the film we see 3 boys hunting together; they go through ceremony and we understand that they are bonded by more than friendship. The film jumps several years and we pick up the characters who are older now and heading in different directions. Miliki is into football and dreams of going to play AFL in the city. Botj arrives back from a Darwin remand centre where he’s spent time for petrol sniffing and other misdemeanours. Lorrpu is strong in his culture and thinks he can help Botj get back on track. The 3 band together to travel to Darwin. Despite their friendship there are strains as Botj stirs up trouble and tries to get his mates to come along with him. After much adventure (I loved the moment when they catch a manta ray and are dragged out to sea in a sacred canoe), they make it to Darwin and there the trouble starts again.

Yolngu Boy was written by Chris Anastassiades (who also wrote Wog Boy) and produced by Gordon Glenn. That the Yunupingu brothers were associate producers is instrumental in the evolution of this film. The director Stephen Johnson established his career making music videos with Yothu Yindi. Yolngu Boy is his first feature. The strength of the film lies in its characters and strong performances by John Sebastian Pilakui, Nathan Daniels and Sean Mununggur. It’s great to hear the sounds of Yothu Yindi, Nokturnl and other Indigenous bands and wonderful to see Indigenous characters and Top End country on the big screen.

–

Yolngu Boy, distributed by Palace Films, is currently screening nationally.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 17

© Catriona McKenzie; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Iron Ladies

Two films so dissimilar to each other as to demolish any definition of Asian cinema in terms of content or genre: a stylish romance set in 60s Hong Kong and a contemporary gay Thai true-life story. Talk about chalk and cheese, but fascinating nevertheless to witness how such diverse products can come to fruition, find an audience and create a market.

Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love picked up prizes at Cannes and has been a big hit with European critics. In parts it is reminiscent of Kieslowski, for better or worse, an appropriately moody love story set in the narrow confines—physically and culturally—of Hong Kong in 1962 where Mrs Chen (Maggie Cheung) and Mr Chow (Tony Leung) are neighbours who discover that they share more than just a common boundary. The realisation that their partners are having an affair forces the lonely duo together, a contradictory position in which they are attracted and repelled by the possibility of becoming like their unfaithful partners. It’s a delicate conundrum which neatly captures the double-edged nature of desire—trying to become what the loved one wants while simultaneously realising that, in doing so, one becomes what one is not.

This low-key discrete affair is played out against a network of mutual obligations and favours, debts and payback, credit and loss. There is a constant process of exchange as characters brush against each other—compliments and greetings, gifts that circulate as symbolic carriers of meaning—and other day-to-day contracts such as arrangements to meet, or part. And when it doesn’t always work, everybody always has an excuse or evasion to maintain appearances.

All this could be very ordinary, an everyday affair, but Wong Kar Wai (and Mark Li Ping-bing and Chris Doyle’s cinematography) imbues it with a suitably heightened perspective. The gorgeous interiors seem to absorb their inhabitants, blocking a clear view of events so that we witness everything through screens and mirrors, at the ends of corridors or off-screen through open doorways. We hardly see the adulterous couple at all, while their play-acting alter egos are constantly in rehearsal, replaying scenes with obsessive compulsion, wanting to know but never for certain. At other moments, the impassive faces of Cheung and Leung are offered up like matinee idols, a seductive blankness hinting at passionate depths, or perhaps nothing at all.

And if it seems as if this could go on forever, that’s because the narrative carefully avoids the regular rhythms of climax and release, crisis and resolution. Instead, the lovers simply continue to miss each other—literally and emotionally—until it all comes to an abrupt stop at Angkor Wat. The spell is broken and, after a lingering last look at the ruins, it is almost as if nothing ever happened.

Meanwhile, elsewhere on the planet, Iron Ladies tells the real life story of Mon and Jung whose dream of playing volleyball is thwarted by homophobic team-mates who refuse to let them join the team. The duo must then enlist the help of gay friends, transsexuals, transvestites and a token straight to build a new team. Will the Iron Ladies overcome blatant discrimination and intimidation to become national volleyball champions? This combination of sport and identity politics, like Priscilla meets The Mighty Ducks, helped to make Iron Ladies the second-highest grossing Thai film of all time. The plot may be fairly ploddy and the message is hammered (spiked?) home but there are enough moments of subversive good humour to keep it alive, such as when the team overcomes a desperate form slump by going into a huddle to apply a bit more lippy (and you thought they were only talking tactics). Wait for the credits with this one to see how art (film) imitates life (television).

In the Mood for Love, writer-director Wong Kar Wai, distributor Dendy Films, opened Sydney March 29; Iron Ladies, director Yongyooth Thonkonthun, writers Visuthichai Bunyakarnjana, Jira Malikul & Yongyooh Thongkonthun, distributor Dendy Films, premiered 2001 Mardi Gras Film Festival, opened Sydney March 15, Melbourne March 22 & other states to follow

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 14

© Simon Enticknap; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Once a year in Adelaide, we come together for the Zoom! ShortsFest, one of the central pieces in the South Australian Film Corporation’s creative development strategy. This series of awards brings together the SAFC, the Media Resource Centre and the SA Young Filmmakers’ Festival, a laudable achievement in itself. The crowning moment of the awards is the Filmmaker of the Future presentation, at which the makers of 2 short films are given a wad of cash, and anointed with this year’s hopes. It is a heady mixture of youthful ambition, small state desperation, and free booze in which to rejoice or drown your sorrows.

We’ve had 2 years of these awards now, brand name recognition is starting to grow and so it’s time to take stock. Basing creative development on an annual competition seems to be part of the post-Tropfest landscape in which young filmmakers are led to believe they can suddenly vault to greatness (or at least a first feature).

The awards system undeniably focuses the local film community’s attention and encourages audiences to watch and discuss local film. It is based on the assumption that an industry can best be encouraged from the top down by establishing a small number of stars, rather than from the bottom up by increasing the level of overall activity in short films. The MRC’s director, Vicki Sowry, made the point that the end of the SAFC’s New Players’ funding scheme would make it even more difficult for Future Filmmakers to make films in the future.

Currently, the top prize goes to the director of a short fiction film made during the year. There are several assumptions here: (1) that we need more fiction filmmakers than documentarists (who are only eligible for the second prize), (2) that directors are responsible for the achievements in the rather vaguely defined criterion of “excellence in visual storytelling,” even though one potential entrant was disqualified for having a Sydney cinematographer (a strange ruling for an event which craves national exposure), and (3) that the state’s development bucks can be wagered on this director on the basis of a single, isolated film.

This year’s awards went some way to laying these concerns to rest. One Day, Two Tracks by Shalom Almond and Tamsin Sharp was a worthy winner and seemed a good bet, as it also picked up awards from the MRC and Young Filmmakers. (Note to the SAFC Board: could we get the TAB to run a book on this event next year? If creative development is going to be run as a competition it seems un-Australian not to let us bet on it.)

The story of a perhaps incestuous moment, One Day, Two Tracks combined an interesting subject with strong performances and a solid professionalism in its visual style. The film was produced with the aid of an SAFC grant, and the directors clearly spent the money well, getting a lot of value for their cinematography and post-production dollar.

This gave me a sense that they were ready to win the award and spend the money fruitfully. One innovation this year has been the stipulation that 20% of the purse go to production-related expenses. The Corporation might consider increasing this percentage, given that the award is supposed to stimulate future films rather than function retrospectively as simply a best film award.

Second prize went to Rachel Harris for There’s a Hole in My Chest Where My Heart Used to Be. Harris has worked within a more artisanal mode of production to make a stop-motion animation employing dolls. We’re in the territory of Todd Haynes’ Superstar, or closer to home, some of the films of Maria Kozic. The central logic of this genre is that dolls are stereotypical representations of femininity to begin with, so they provide an appropriate form in which to comment on broadly social gender roles. This allows for postmodern self-consciousness combined with the didacticism of a Barbara Kruger. Harris’s film manages to rejuvenate its heavy social comment with a good deal of visual inventiveness, which earned it an MRC award for best design.

One of the problems that the judges undoubtedly faced was that the 27 entries represented wildly different conceptions of what short filmmaking is, and indicated a variety of backgrounds and ambitions concerning possible futures in filmmaking. Mike Theobald’s Deadline, which won the MRC’s editing award, is the opposite in every way to Harris’s film. Theobald has clearly made the film as a calling card for a career in commercial filmmaking. It is your standard slasher-chases-isolated-woman movie, designed to showcase professional skills rather than to produce interesting film. While we need all the good commercial filmmakers we can find, it seems a shame that Theobald understands commercial filmmaking as merely the replication of generic formulas rather than the reinvigoration of them.

If Theobald wants to become John Carpenter, others in Adelaide would prefer to be David Lynch. This brings us to another model of short filmmaking, which is the abstract, dissonant essay on the loneliness of Existential Man. Two examples are Jack Sheridan’s Solipsis and James Begley’s Buggin’, which won the MRC’s cinematography and sound awards respectively. Both films are based around lone protagonists who have isolated themselves in pared down rooms. In both cases, the spare mise-en-scène and lack of dialogue allow scope for the formal elements to come to the fore.

On the whole, I suspect that the strength of the films this year left people feeling more positive about the awards systems than they had hitherto been. However, those members of the film community who see themselves as clients of this system look forward to some discussion of it. Both years, the judges have commented on the anomalous position of documentary. This is an obvious issue that needs to be addressed. For example, I’d personally have given some encouragement to Amy Gebhardt for her SBS doco, Gepp’s Cross Drive-In, a vibrant celebration of community within a set of sub-cultures rapidly passing away before us.

I suspect that in the long run (if there is such a thing in any Australian film industry), these awards will be judged by the subsequent successes of their winners. Let’s hope that the results will justify the system quickly.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 17

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

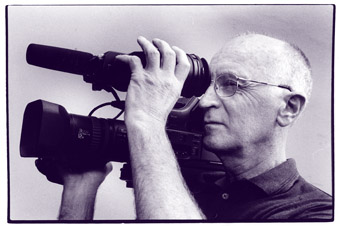

Valerie Lalonde & Ricky Leacock at the conference

photo Peter Hasson

Valerie Lalonde & Ricky Leacock at the conference

The Australian International Documentary Conference (AIDC) is a chimera, part supermarket, part artistic intellectual pursuit, part rebellious belligerence.

This year in Perth these powerful forces were much in evidence. Pride of place was given to cinema verité documentary-maker Ricky Leacock, documentary prankster Craig Baldwin and US filmmaker Fenton Bailey (The Eyes of Tammy Faye). Bailey sheepishly admitted, while sitting on a panel with the other 2, that he felt he survived in a “highly compromised way” by doing 2 types of work—those which he was passionate about, and those which paid the bills. The presence of commissioning editors from television broadcasters around the world also meant he was unwilling to identify which work was which. Leacock showed no such compunction and set about roundly abusing commissioning editors, listing the films and the broadcasters who had rejected them over the years. You can get away with that when you’re 80.

Leacock wasn’t the only person at the AIDC doing what he wanted to do in the way he wanted to do it. During a forum entitled “Self and Semi-Funded Projects”, younger filmmakers showed how they were able, through a combination of skill and sheer determination, to get their documentaries made and screened. Australian Janine Hosking, director of My Khmer Heart, is currently riding high on a sale to the US network HBO for her 95 minute documentary about Australian Geraldine Cox and her Cambodian orphanage. Hosking and her partner, Leonie Low, worked 4 jobs and called in favours from camera crews they knew from their time as current affairs producers to get the job done. Their crew accepted a deferred payment option, taking their fee once the film had been sold. Hosking is relieved now that they have been able to pay their friends but admits to some sleepless nights when things didn’t look so rosy. As an explanation as to why she didn’t seek funding from Australian funding bodies her reply is pragmatic, “We wanted to make a documentary, we didn’t want to spend our time filling out forms and waiting 3 months for the next funding round. The story would have disappeared by then.”

Annabelle Quince, writer/director of Watching the Detectives, admits that if she had been able to see the road ahead of her in 1993, when she had the initial idea for her documentary, she would never have proceeded. Quince, a producer on Radio National’s Late Night Live program, found that in applying for funding her track record in other media was not recognised. As the years passed, she saw the innovative idea she wanted to explore in 1993 become mainstream and fly-on-the-wall documentaries become the popular choice for funding. Quince admits that a certain bloodymindedness, and the promises made to women detectives she had met in the USA, helped push her to finish the project. A small handheld camera, a DAT recorder and a 4-week shoot in the USA in 1999 saw her project move towards fruition. It was finally completed after some post-production funding.

Documart, where filmmakers pitch their ideas to commissioning editors from television broadcasters, has something of the flavour of Christians being fed to the lions. The filmmakers take the part of the true believers, while commissioning editors give the thumbs up or down. Along the corridor was a master class on the possibilities of the internet, computer software and non-linear narrative. There was the chance to ponder the fate of The Real Mary Poppins‚ a documentary pitch (will it fly?) which saw interest from international broadcasters like the History Channel and A&E Biography while at the same time exploring whether broadcasters, exhibitors and distributors will even be necessary to documentary in the future.

The internet, DVD and DVD-ROM explode the idea of linear narrative and transfer much of the narrative control from the filmmaker to the audience. It is no surprise that this is something that captivates Leacock. For filmmakers whose ideas were rejected at the Documart, Leacock must stand as an inspiration. He is delighted with the possibilities the internet gives him to engage with an audience without kowtowing to broadcasters’ opinions: “I’m looking for an audience, not of millions, maybe only a couple of thousand people who can enter into dialogue with and about the work.”

Rejection is where the art is in Documart.

Australian International Documentary Conference, director Richard Sowada, Sheraton Hotel, Perth, March 6-9.

RealTime issue #42 April-May 2001 pg. 18

© Mary O’Donovan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rushing to Sunshine

In a scene from Solrun Hoass’ latest documentary Rushing to Sunshine a fisherman from South Korea discusses the media coverage of a recent ‘incident’ in which the South Korean navy sank a North Korean fishing trawler. He says: “There are no reporters who report the whole story. They all add a little bit and take out a little bit.” He is media savvy, which it seems the South Koreans need to be, if they are to avoid becoming legal ‘traitors.’