Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

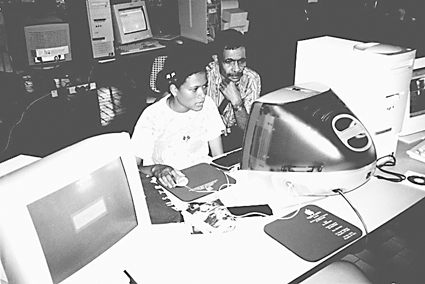

With access to funding more competitive and scarce than ever, the relationship between universities and dance artists seems to have gained new significance. The academy has been a traditional source of valuable employment for many dancers and choreographers but a new dimension has recently appeared where choreographers are engaging with the research paradigms of universities. Melbourne has seen a steady growth in the number of practitioners returning to do postgraduate studies in dance as a way of deepening their practice and extending their careers. The universities have also become more explicit in their demands that practitioners who are also lecturers/teachers become better qualified academically. This has led dancers to engage with theoretical constructs in ways that did not exist 10 years ago. But what sort of a marriage is it, this meshing of the academy and practice? And how do the artists themselves view the intersection of dance and theory? The relationship is in continual flux but talking to 3 Melbourne choreographers and a performance maker, some interesting themes emerged about this occasionally uncomfortable relationship.

For choreographer Anna Smith, who teaches technique sessionally and is a research associate at the Victorian College of the Arts, the relationship is clearly positive. She is appreciative of the support and access to resources the work gives her and is philosophical about the impact the teaching work has on her own practice. She often finds it problematic trying to separate her teaching from her choreographic practice, even though both require a different focus and intent. But she says, “I have to be pragmatic about it and value it for what it gives me which is space in the studio and a lot of support—not just financial support but also people walking in. I could grab someone in the hallway and say could you just have a look at this.”

This appreciation of the support universities provide was echoed by all the artists I talked to. The job of teaching itself was also often a big attraction. Dianne Reid, ex-Dance Works dancer, choreographer and dance-video maker has been teaching technique, composition and theory at Deakin University’s Rusden campus for 4 years now. Teaching for her is an extension of her skills as a performance-maker and an opportunity to try new ways of delivering the material, such as her highly performative lectures—a major hit with first year theory students. She loves the investigative environment of the university which leaves her free to experiment and tailor courses which reflect both her own artistic interests and the needs of the students. She is currently developing a dance-video unit for third year Bachelor of Contemporary Arts students, allowing her to combine teaching requirements with her passion for dance and the camera.

The downside of having an ongoing position is the loss of profile. Suddenly Reid has become strictly a dance educator not an artist, something that clearly rankles. “You tend to disappear in people’s eyes when you are at a university.”

The sheer workload for full-time teachers also has an impact. Multi-disciplinary artist Margaret Trail (not strictly speaking a choreographer but whose work is often seen in dance contexts such as Dancehouse) has been teaching full-time for 2 years at Victoria University of Technology in the Performance Studies course. While she loves teaching, the first 18 months of full-time work were challenging. Rocked by the demands of the workload and the new administrative responsibilities of the full-timer, she was left with no choice but to concentrate wholly on the job itself, to the detriment of her practice. “I do get enormously frustrated with the university and that’s compounded by the fact that as a full-time staff member you can’t walk away. You have to take the university on. You have to make a relationship with this bureaucracy which is often dysfunctional, which tends to undervalue teaching, which is increasingly driven by economic, not educational motives and you have to survive inside it and feel alright.”

High profile choreographer Lucy Guerin did a stint of teaching technique and choreographing at the Victorian College of the Arts in 1999 and felt uncomfortable with aspects of the job. To be responsible for the training of students and to respond to their multifarious needs weighed heavily on her. “I’m really happy to go in and give people a taste of my work and my choreography and where it has come from—what its technical origins are. But in terms of teaching long-term and taking responsibility for people’s development, I felt I couldn’t really take that on in the way they needed.”

However, Guerin saw the opportunity to choreograph as beneficial and a way to develop her ideas with a large group of dancers otherwise impossible for her to access. In so doing, she saw the process quickly shift from being exclusively about her ideas to also becoming a response to the needs of students. How could she achieve a common stylistic understanding from 19 dancers of different abilities and yet foster a personal investigation and embodied awareness of her choreography? She relates the almost rigid approach of some students to the legacy of dance training throughout Australia. Tired students are striving to reach a standard of technical excellence that is perceived to be appropriate for the professional arena. The demands of this kind of training leave little time to concentrate on investigation and experiential understanding of movement. “It’s not the fault of the institution. They are very aware of these problems. It’s just how to implement [the changes] within this kind of structure which is subject to all this history. The students come in with particular preconceptions about what they are going to be doing and it’s quite hard to break them down.”

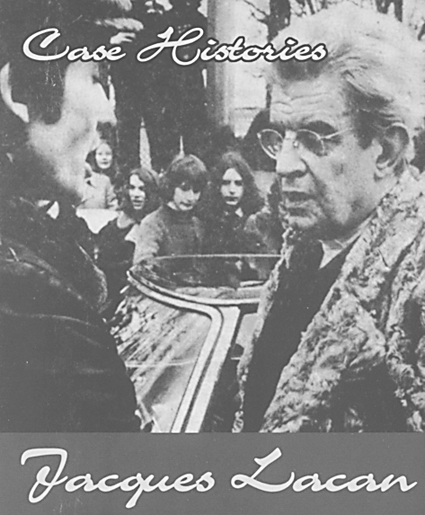

Another major challenge for practitioners working within universities, and one with huge potential implications, is negotiating the vexed issue of theory and dance. Traditionally resistant to entering this domain, many dancers and choreographers, either through postgraduate degrees or as lecturers, are now being asked to rigorously confront theoretical frameworks and use these to analyse and inform their practice. It remains unclear how this will change the ways artists create or think about their work—the relationship between dance and theory is still nebulous and few choreographers currently write about their work. If the growth in practitioners doing postgraduate research continues, a major shift in approach will surely follow. But how do practitioners feel about the meeting of theory and practice? Although wary of the academisation of practice, Margaret Trail says, “I’m terribly interested in that cross-over because to me it has only ever been productive, although I do think they are 2 different ways to process information and I never take my Lacan down to the studio. Still, encounters with theory have only ever been exciting and wonderful and have opened things up in practice.”

Certainly, doing justice to both the theorising about and making of dance work is difficult. It requires skill in juggling and expertise in very different forms of knowledge. Writing takes just as much practice as dancing, which can then interfere with the experiential nature of the studio work and even the needs of dancers’ bodies. Research into dance has its own needs but the body of writing on dance research remains comparatively small and is still justifying its own place in many universities. Questions also remain about the balance of practice and research and the impact they will have on each other. But Dianne Reid, who has been granted research leave by Deakin University to take part in Luke Hockley’s forthcoming project at The Choreographic Centre, sees the emerging relationship as moving in the right direction. As long as artists remain proactive and have clear plans about how to work within the institution, they can develop a positive relationship. “There’s more and more understanding and support and inquiry into research into the arts which we used to just call working or rehearsing or process but really it’s the same thing.”

–

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 14

© Shaun Davies; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Abracadabra opens Reel Dance and, as with any good password to any good world of wonders, transportation begins immediately. Phillippe Decouflé’s 1998 dance film (France) is an excellent password for this particular dance film festival, which goes right past mundane questions of ‘is it really dance?’ to the much more intriguing questions of how physical languages and cinematic languages might intersect. Abracadabra begins at the beginning of this question by linking dance to early cinema. A series of what film theorist Tom Gunning calls “attractions” are displayed. The word attraction partly refers to attraction as in circus act or novelty. Decouflé revels in this meaning, presenting danced oddities and bizarre displays with great glee. Then there is the attraction people have to the trompe d’oeil or cinematic trick of the eye. The viewer’s eyes are tricked overtly and inventively through various devices in Abracadabra, such as the use of deep focus creating illusions of outlandish differences of scale between foreground and background objects and actions. The final vignette is an acrobatic display in which the dancers do incredible things which, with enough skill, could really happen in the real world. These displays then evolve into the hilariously impossible and the audience realises a cinematic trick is being played on them. Both senses of the word attraction apply here—the acrobatics are an attraction or an act, and the moving image is itself a trick of the eye that attracts our attention.

This combination of attractions is one of the things that Reel Dance seems to propose defines dance on screen: physicality far enough outside of the norm to present itself as an attraction, combined with the many cinematic conventions that have evolved through and since early cinematic tricks of the eye. It’s not exactly a new form, but it’s an intriguing combination—making use of the conventions of cinema with dancing rather than acting as a vehicle for conveying content.

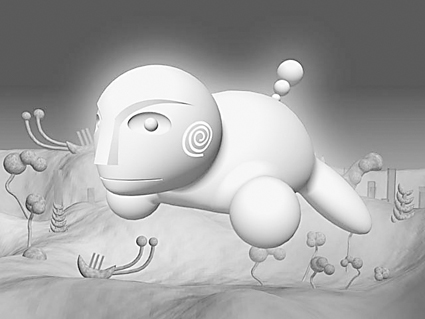

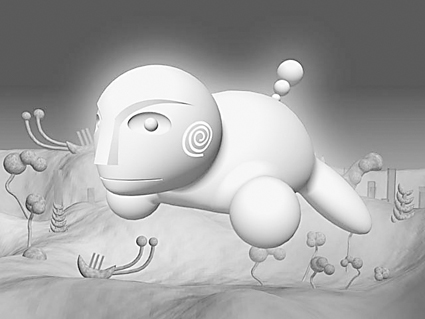

This combination was explored throughout the weekend, with many of the films drawing on particular film genres and infiltrating them with particular forms of dance. Dancers from the Frankfurt Ballet were involved in an overlong but intriguing dance in the genre of science fiction called The Way of the Weed (Belgium). Wim Vandekeybus contributed The Last Words, a magic realist fantasy film driven by physicality rather than being about it. Nussin (Netherlands), brilliantly directed by Clara van Gool, referenced gritty, naturalist filmmaking, set in a run down housing development in the middle of an icy winter. Combining this cinematic style with the tango, a most elegant, precise and aristocratic dance, created a feverish heat and chilling beauty.

Not all films were equally successful in their intersection of the capacities of cinema with physicality although the 2 films that appealed the least shared the prize for Best Screen Choreography at IMZ dance screen 99. Margaret Williams’ Dust (UK) felt like it drew mainly on the cinematic conventions of advertising with its beautiful but meaningless shots, textures, angles, cutting and sound. Her film Men irritated with its cute humanism, exploiting men over 70 and beautiful landscapes—just like a National Geographic documentary making the extremes of nature into comfortable TV.

On the other hand, La Tristeza Complice (Belgium), a film which exploited the cinematic tradition of verité documentary most subtly and poetically, was not an audience favourite. Perhaps people were irritated by the grainy degraded quality of the image and the odd marks and scratches which flashed by on the screen. However, these could be viewed as cinematic expressions of the subject matter, the elevation of the everyday, degraded and scratchy as it may be, to the status of image, and the manipulation of the dynamics of those moving images into an aria of the ordinary. Verité documentary often has odd flashes of beauty caught more by perseverance than by plan, and this film seemed to make a choreography of these images of dancers laughing, eating, smoking, arguing and passing the languages of their bodies and lives to each other. The film was itself a dance, made in the editing suite, and, since it is documenting a rehearsal, the editor’s marks—the chinagraph pencil marks for dissolves and cuts—were left on the image as clues to the working process of making this film dance.

The selections representing Australian work in Dance on Screen, as finalists for the Reel Dance Awards, were surprising and intriguing, the films presented in the historical retrospective session a bit less so. It is certainly tricky to present a whole country’s output (since the beginning of its engagement with the form) in one session, which perhaps explains why, in a festival that had a very strong curatorial vision throughout, the retrospective session seemed to lack focus and momentum.

However, in the Dance Awards screening, a much stronger through line appeared. There were very few well-known dancers or dance companies—almost none of the usual suspects. Instead, maverick filmmakers experimenting with the moving image through the device of moving bodies prevailed. There was a strong emphasis on the choreography which takes place in post production—after the dance has been danced and the film has been shot—through editing and digital effects. The tricks of the eye become trickier, more apparent, less illusory precisely because they couldn’t possibly happen in ‘real life.’ But as manipulations of the moving body they are the definition of choreography. They are the manipulation of the dynamics, rhythms, shapes and causes of movement, even though a real body could never do these ‘post produced’ moves. They are dance attractions engaging with the new form of cinematic attractions—the digitally generated tricks of the eye.

Finally, there were even magic words uttered at the closing ceremony of Reel Dance. Annette Shun Wah, chair of One Extra, expressed the hope that Reel Dance (a One Extra event) would “inspire”, and sent the spectators forth from this world of wonders, saturated with the potency of its images and ideas, to create next year’s attractions.

One Extra Dance Company, Reel Dance, curated by Erin Brannigan, Reading Cinema, Sydney, May 19-21

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 15

© Karen Pearlman; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

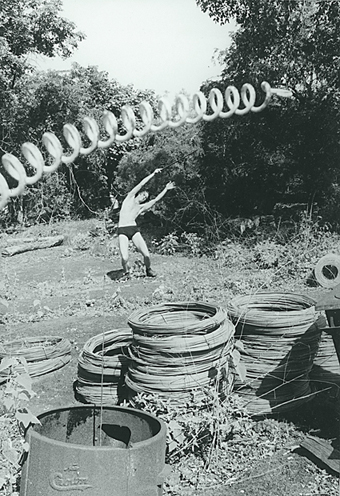

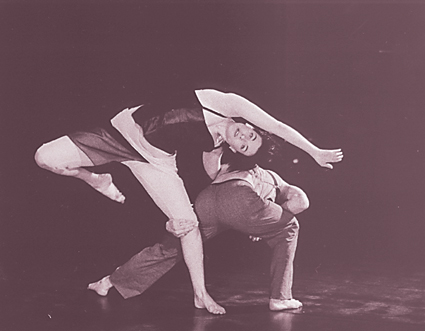

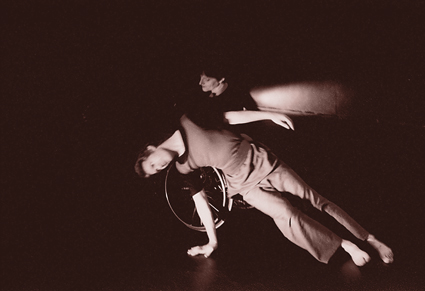

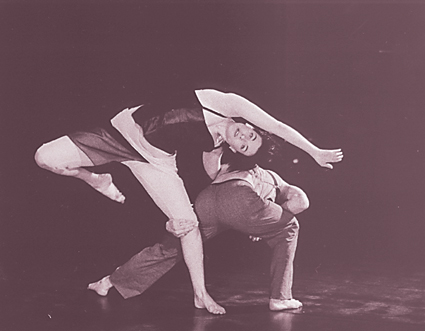

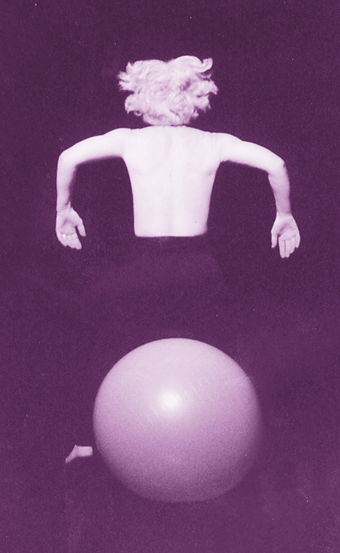

David Corbet & Janice Florence

photo Ryk Goddard

David Corbet & Janice Florence

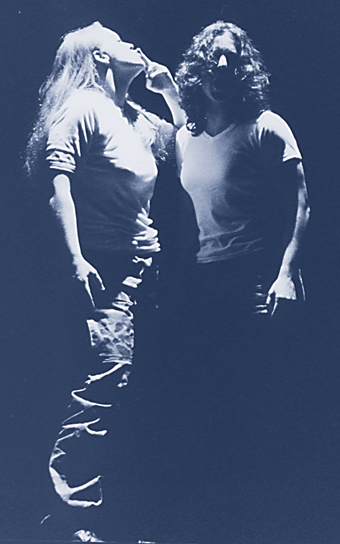

Improvisation in whatever artform is about freedom; freedom of expression at the most overt level, throwing off all the restrictions and codes of artistic practice and replacing them with a spontaneous exploration of the very process of creating art. That it is art in process and simultaneously ‘in product’ is what places us, as observers, in a new relationship with the performers.

In dance, improvisation as a mode of performance represents fluidity, play and impulse, in contrast to the often rigid structure and form of choreographed movement. Sally Banes, in her 1993 text Democracy’s Body, describes improvisation’s extremity best: “If all dance is evanescent, disappearing the moment it has been performed, improvisation emphasises that evanescence to the point that the identity of the dance is attenuated, leaving few traces in written scores, or even muscle memory.”

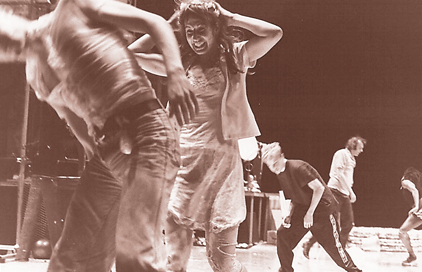

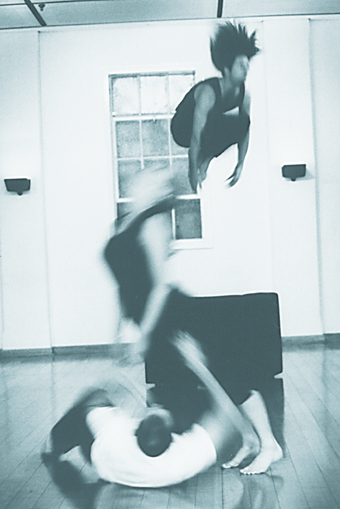

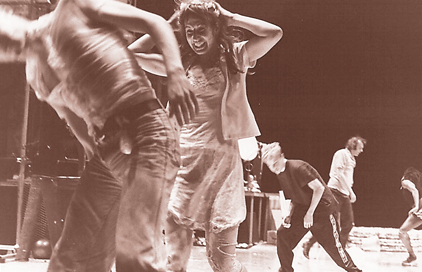

In May, the Choreographic Centre hosted a weekend of improvisation, featuring the work of 4 groups that have embraced improvisation for the development of their performance. Familiar to Melbourne audiences, the groups were in Canberra as part of the third annual Precipice event.

Peter Trotman and Lynne Santos

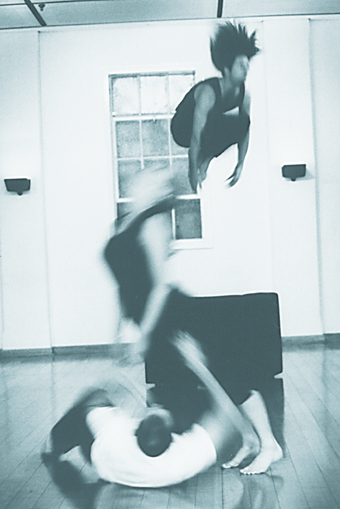

Their improvisation starts with heavy movement—arms sweeping. Then it floats—the hands flexed. They are giving into their own weight, moving in isolation and yet there are moments of connection in the randomness. The pace increases and the movement becomes more abrupt, but there is still a seeming softness to their joints.

There are static moments; then they are leaning into and later onto each other, pushing away and falling upon. There is a fluttering of hands. “Heart beating pulse racing eyes blinking tongue licking,” Trotman blurts out. There’s a story to this performance, but where it ended up I have no idea…

State of Flux

The focus here is more on contact improvisation…physical support, touch, suspension of weight. The duet between 2 of the performers, one in a wheelchair, conveyed the honesty of contact improvisation. There are chance funny moments…he balances on her lap, shifts position his bum is in her face…and intimate moments…wheelchair discarded, rolling on the floor, moving over each other…and some pretty clumsy moments too…the uneasiness and heaviness of it all, bodies not intuitively sensing each other’s next movement. Sometimes it seems like the distance between the individuals is expansive; at other times it seems like the group is a single entity.

Five Square Metres

There’s a definite frivolity to this group; the 4 performers are expressive and frequently quite silly. The wit and chatter is all a vital part of the improvisation. The use of breath is another clever layer of the performance…sighs, deep inhalations and exclamations, all uttered on top of each other and set against equally staccato movement, such as shuffling in file and bumping into each other. There seems to be more of a narrative than in the other events on the program. The movement is but one element of the performance, and more driven by the group than the individual, almost a kind of expression of community.

Gallymaufry

Andrew Morrish brings out his mike, Madeleine Flynn plucks her violin and Tim Humphrey toots the trumpet. Morrish does most of the talking, absurd little phrases really, amusing as part of the situation, “I’ve been dreaming after hours.” The music is cartoon-like in the way it complements his prattle. He steps away from the microphone, arms reaching, then stretching gently, he steps out into more dynamic movement. Humphrey is yelling, “Open that door and jump!” Is it a command for Morrish or for us? Madeleine goes to the accordion and Morrish is moving again. It’s the funny mishmash of music, word and movement that gives the performance its meaning.

In an evening full of humour and more than the usual risk-taking, these groups created new performances and challenged us as observers to do a little risk-taking of our own.

Precipice: on and over the edge, The Choreographic Centre, Canberra, May 26-28

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 15

© Julia Postle; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

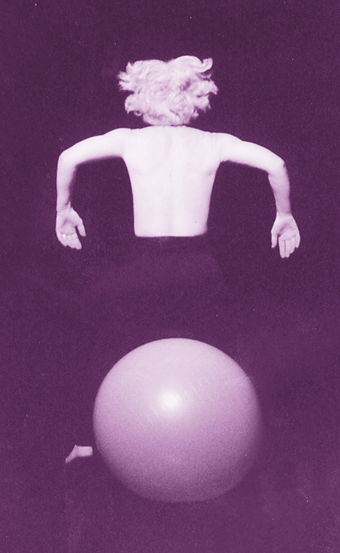

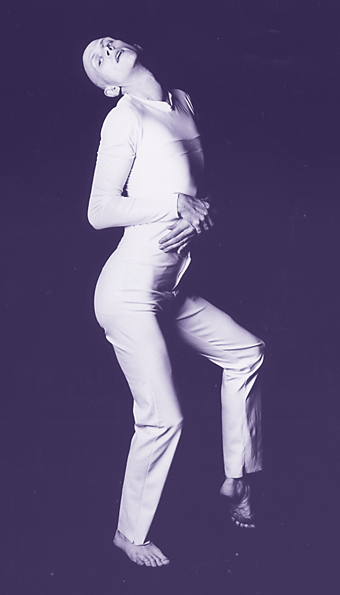

Stark White

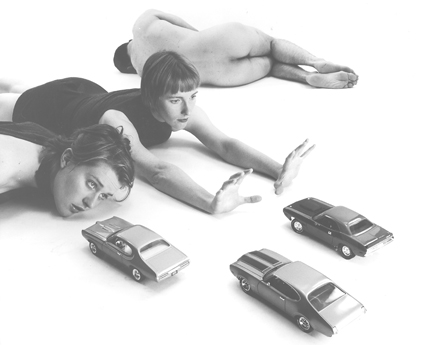

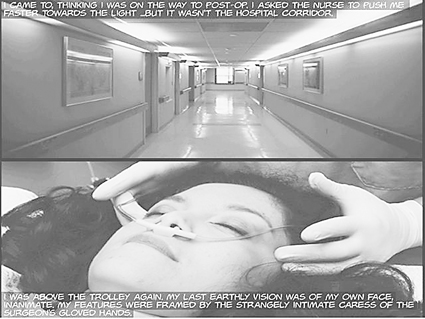

The centrality of the abstract yet highly physical concept of the body in contemporary criticism renders our material form as the supreme subject of cultural, psycho-physiological forces. From Sigourney Weaver to genetic engineering, Artaud to dance music, the body has become a mesmerically omnipresent object which is gazed at, deconstructed, theorised, disciplined and choreographed. Choreography and criticism replicate a form of social violence which the body must routinely endure.

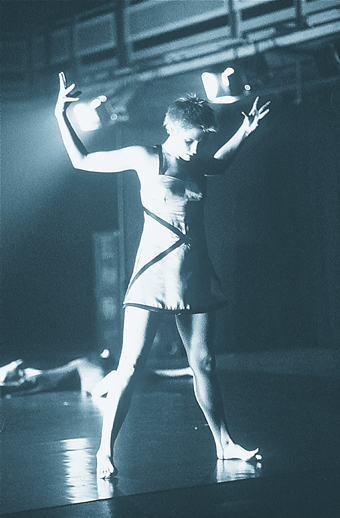

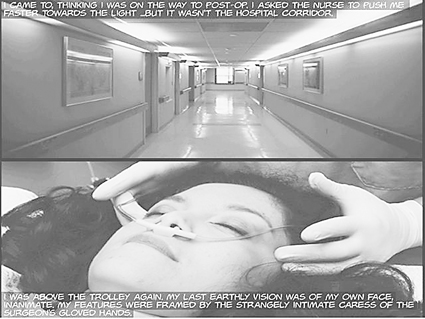

This insensitivity to the needs of the body as a living body—a critical-choreographic refusal of the soft body—is forcefully rendered in dance-maker Brett Daffy’s film Stark White. Daffy formerly acted as the archetypal self-mutilating, queer ‘hard-boy’ of Gideon Obarzanek’s early choreography and his independent dance proceeds from this precedent. With Stark White, Daffy’s disconcertingly pliable anatomy is pulled apart and reformulated in horribly compelling, ‘unnatural’ ways. This happens both internally—Daffy choreographing Daffy—and externally—women pulling at his limbs, angrily manipulating his joints, and grabbing at his form, before these bodies too undulate under the influence of an internal, psychophysical aphasia. The dancer moves from the bewildered voyeur of others’ psycho-somatic abjection to the primary subject of these forces, awakening to find himself enmeshed in an Escher-like landscape of physical and architectural repetition.

Brett Daffy extends this choreographic violence into the cinesonic language of Stark White. He and director Sherridan Green reject the tendency of dance film to sew together isolated frames so as to reconstitute a single, moving body. Image, sound and gesture are fragmented by the very processes of filmic production, and there is little attempt here to bring them back together. Stark White is not a montage of random material, but it does not conceal the brutality of its production. Like the protagonist, the audience is forced to recall its own position as producer of the cinematic experience—as flickering eyes and aural filters—fragmenting the film even as one attempts to draw it into coherence. Daffy, Green and composer Luke Smiles are therefore unconcerned by the body lying out of shot or gaps in the linearity of sound and image. The film jumps and shudders, creating something akin to a great, fleshy car backfiring crystalline apostrophes as it bunny-hops down a tinted, scratched subterranean road.

Daffy nevertheless prevents his work from becoming consistent with implicitly sadomasochistic, misogynistic or simply oppressively voyeuristic modes prevalent in advertising, painting (especially the nude), dance and ballet. He achieves this by placing himself and not the women at the centre of the literal and metaphoric technologies of the work. The cinesonic focus and choreographic violence spirals around his form and disorientation, his alienation and recovery. After seeing him both literally and metaphorically stripped and shaved, our gaze forces his body into the realm of sexual ambivalence and ambiguity. He is transfigured, a queer Christ perhaps. Like Calvin Klein’s models, Daffy lies beyond the heterosexed. Unlike advertorial homoeroticism though, this transmutation (this crucifixion?) is achieved through ecstatically painful dismemberment, by cathecting bodily parts and gestures such that monsters are born. The finale leaves us with this sexual beast flipping through the axial patterns elaborated in Leonardo’s Ecce homo, yet menaced by the possibility of psychological, sexual and physical hybridity that one sees in Hieronymous Bosch. A post-human for our age of monsters.

Stark White, writer/choreographer/ performer/producer Brett Daffy, director/ editor Sherridan Green, sound score Luke Smiles, Motion Laboratories, performers Sally Smith, Larissa O’Brien, Sharilee Brown, Lina Limosani, Ben Gauci, Larrissa McGowen, Paul Hickman, Kathleen Skipp, Anna Smallwood.

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 16

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

66B/cell, Cybermyth

Fusion, n. Fusing; fused mass; blending of different things into one; coalition

“…when two strange images meet, two images that are the work of two poets pursuing separate dreams, they apparently strengthen each other…”

Gaston Bachelard, Poetics of Space

Fusion was an evening of multimedia presentations, a part of the St. Kilda Film Festival program. Curator Sue McCauley successfully brought together a range of material with the stated aim of exploring the interactive possibilities of digital media. The program was scheduled to take place in 3 separate sessions. The first introduced several new innovative CD-ROM works; the second focused on the demonstration of a number of politically charged interactive documentaries; and the third showcased a variety of performance pieces which also incorporated digital material.

Curator Sue McCauley comments: “As the curator of the program for the second year in succession, I knew that the festival and particularly the venue was a fantastic opportunity to showcase the latest in CD-ROM and performance. It is not often that artists get this sort of opportunity. As a survey type, I felt that I could do 3 very different sorts of programs where artists could demonstrate their works for the general festival-going audience.

“I have recently also coordinated the digital arts program for the Next Wave Festival, Wide Awake Dreaming at Twilight. In both events I focused on creating contexts for the exhibition of multimedia works that did not rely on viewers looking at works on the computer. I was interested in getting away from the idea that the site of production was the exhibition platform. I want to give artist the opportunity to escape the box when showing their work. So works were incorporated in installation, in theatrical peformance or as installations.”

It has become common practice to incorporate CD-ROMs into film festival programs. In the last couple of years at the Melbourne International Film Festival, exhibitions of multimedia works have been set up in foyers and adjacent gallery spaces enabling patrons to move between film screenings and the interactives. There were, however, several things that made the Fusion program quite distinctive. First was the diversity of material that was presented—a demonstration of the real range of work currently being undertaken. Second was the impressive way that a human presence was brought back to the centre of the multimedia stage. This took the form of the creators of the CD-ROMs actually presenting their work, taking the audience through some of the pathways of their creations, and answering questions about the work and the creative process. It also took the form, in the final session, of a number of manifestations of the performing body, from playfully acerbic monologues to high-tech choreographed dance ensembles.

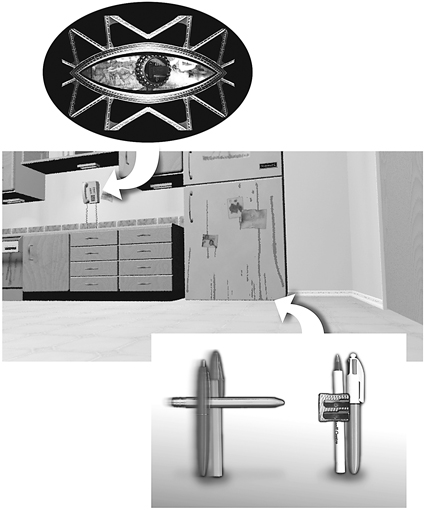

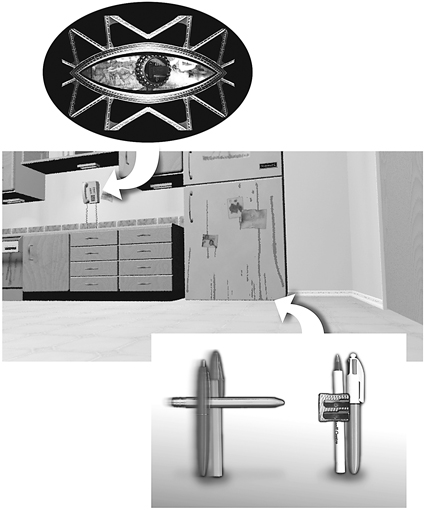

The first session, Surface Tension, featured 2 CD-ROMs which could be described as explorations of personal spaces and the subterranean, shifting zones beneath the surface of things. Leon Cmielewski and Josephine Starr’s Dream Kitchen is an interactive stop-motion animation. The space for this interactive is a pristine, gleaming kitchen setting. Cmielewski explained that the concept originated in a story from Japan where people put on VR helmets to see what their dream kitchen might be like. Once we start to explore this dream zone, however, we encounter ‘eaky borders’ which allow us to slip into the oven, under the fridge, down the sink. Here we discover debris, missing pens and pencils, and rodents: we are even able to administer electric shock to a rat. Each return to the kitchen space finds it in increasing disarray—dirtier, messier, falling apart. In comparison, the space for Matthew Riley’s Memo is more personal and meditative. Riley’s idea was to create an artist’s diary full of hand-drawn, painterly sketches and scrawling text in a high-tech medium. He wanted this journal-like structure to incorporate his many observations of the relationships between popular culture and the everyday. And he felt that interactivity would enable him to suggest complex conjunctions of meaning between situations as diverse as phone sex, football, gambling, and shopping, with a focus on the different ways in which language works.

The second session featured a series of interactive documentaries with tough political and educational agendas. It became clear that interactivity has provided practitioners with many new opportunities. It was also evident from the work that the interactive form of documentary has become the site of close callaboration between the subjects and the storytellers. Filmmaker and activist Richard Frankland introduced the CD-ROM The Lore of the Land and spoke of the way Fraynework Multimedia’s work supported Indigenous people in telling their own stories by not editing the material that they have collected. Similar sentiments were expressed by those who worked on the disturbing and poetic East Timor Identity, Resistance and Dreams of Return. The producers saw themselves as facilitators encouraging the stories of East Timorese refugees in exile to be told. The final documentary, Mabo: The Native Title Revolution, turned out to be an equally interesting hybrid that includes a re-edit of filmmaker Trevor Graham’s Land Bilong Islanders with a new ending taken from his other film Mabo: Life of an Island Man. A great deal of extra material has also been gathered together into this CD-ROM to make it a valuable research resource with clear educational potential.

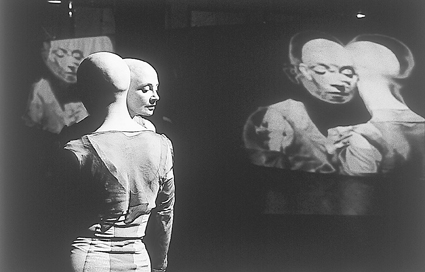

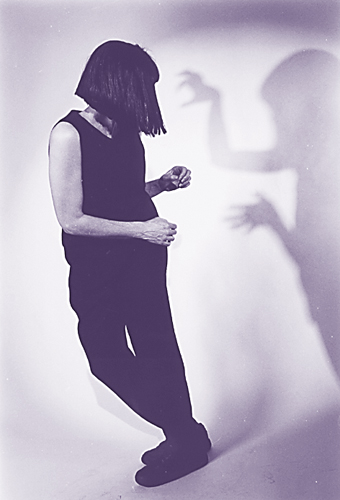

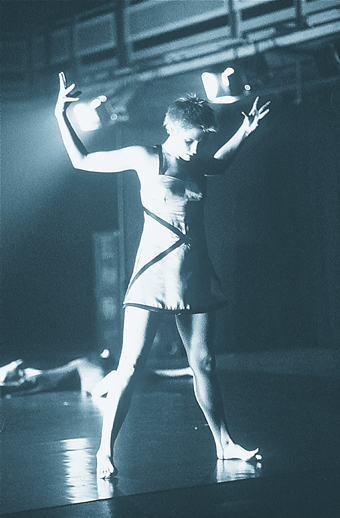

The third session was the most provocative and high octane. Live performers interacted with digital projections of pre-recorded images—a fusion of voices, bodies, and dancing limbs in a multimedia theatre-scape. Frank Lovece’s Poopants was a voice-driven work dedicated to narrative. Lovece’s fast-track monologue touched on issues of violence, the republic, race and class as his words and voice interacted with projected image fragments. A series of screens and structures were strategically set up on stage to further break up and fragment the images, and complicate possible readings or interpretations. The next 2 performances were Cazerine Barry’s innovative dance works. Pony Girl took its inspiration from Girl’s Own Annuals and Barry’s prancing, energetic body took mock riding lessons from a 60s style projected voice. Lampscape was a more mesmeric piece with Barry dancing behind a large gauze screen shadowed by, and interacting with, images of herself projected through the screen—a theatre of the figural. The final performance was a futuristic work of alchemy which came from the Tokyo-based collaborative group 66b/cell’s Cybermyth, a collaboration of Japanese and Australian performers. The work they presented was a remix of Goethe’s Faust—a kind of Faust in Space—with characters plucked from the text free-form, clothed in graphically striking cyber costumes which intermittently flashed and created their own light shows, performing choreographed Butoh-inspired dance movements which also incorporated digital video projections. During question time, one of the artists explained that they had tried the piece with visuals alone but felt that it wasn’t enough. The stage, they said, needed a human body.

This was one of Fusion’s real achievements. Invoking McCauley’s words, Fusion was a program which “escaped the box”.

Fusion, St Kilda Film Festival, The George Ballroom, Melbourne, June 2

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 20

© Anna Dzenis; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Anyone interested enough to pass by the Stock Exchange building in Sydney a few months ago would have witnessed the spectacle of the dotcom crash, or “new media adjustment”, as financial pundits would have it. Small-time investors and internet start-up owners stood, some with noses unselfconsciously pressed to the glass, watching their stock devalue minute by minute. Informed by the U.S. NASDAQ (the American financial index for new media stock) the electronic red ticker streamed a sorry story; some stocks nosedived to within a hair’s breadth of their issue price, others simply entered negative figures.

The crash came at an interesting time. In internet years (roughly comparable to dog years in terms of development), the web was colonised by technology corporations a very long time ago. They are responsible for both interpreting the web as a rampantly commercial space (with all that that entails), and developing sophisticated platforms from which to serve what they call “content”, a lazily defined term which means anything from editorial to a nifty, Java-scripted button on a navigation bar. Strategies ranged from providing millions of free email addresses and giving away software to skimming a percentage off the top of credit card purchases. Very few of them made actual money and the market eventually got nervous, hence the crash. Things, as they say, will never be the same again.

The development of the technology, however, continues apace. WAP (Wireless Application Protocol) will be coming to someone with a fairly hefty mobile phone plan near you very soon, delivering components of the web (news headlines, movie session times, sporting updates and of course stock reports) to the thing that just used to go ring ring. Interactive TV has already been introduced, and Pay TV viewers are familiarising themselves with the idea of fusing a website interface with broadcast programs—checking their email while the cricket is playing. All pretty handy.

So what’s an article about a bunch of well-off wankers losing their money during a period of vastly accelerated technological growth and innovation doing in RealTime? Serving as speculation, mainly, about what all of this means for the way in which information we want to find and “content” we might very well create, will be disseminated in the future. These emerging technologies will indeed be handy, but who will be setting the agenda as to how they are used? In a post-crash environment, where the cash won’t be flowing anywhere near as freely as it did before, the web as it spreads to TV and your phone will be economically rationalised. Internet service providers of all kinds now have a vested interest in keeping their subscribers within the walls of the content that they have purchased or aggregated. Some are giving away free access—you don’t pay a cent, but you can’t actually leave the network you’re in to explore the rest of the web. So if you’re forced to bank online because your local branch has closed down, and you can’t afford to pay for an internet connection, welcome to the “walled garden.” Others provide services exclusively to their paying customers; everything from 5 email addresses to animated short films and “superior” news coverage. Stuff the rest of the rabble will never see, unless they upgrade.

Of course it’s all in the name of commercial good sense, but does it have to be inevitable that the medium that started as a tool for Cold War military communication, transmogrified into an academic language (Hyper Text Markup Language or HTML) and still boasts worldwide access to information about subversive and marginalised cultures, will become a segregated medium?

Firstly, to the culture. The internet industry workforce is home to some of the most brilliant technology heads outside of the science world. They are able to solve problems more quickly than it would take to explain them, and remain wisely apolitical within the sphere of the working day; a geeky empire unto themselves. But the industry is still bloated with counter-culture poseurs; under 35 year-olds with Palm Pilots and wardrobes full of utility chic couture, spouting new media pseudo ideology-speak as flimsy as the content they are responsible for publishing on the web. Attend a meeting with these kids and buzz phrases such as “synergy” (a greasy economic fit between 2 businesses) and “robust nature” (the ability for “content” to be pillaged for e-commerce opportunities and syndication models) will zap around the room like so much locally routed data. It is very possible you will witness them encouraging each other to “think outside of the square” (come up with ethically unsound solutions to content problems, such as sell the arts section of a website to a sponsor and skew the editorial in its favour). And if you’re unlucky enough to suggest something which doesn’t have a “fit”—even outside the square—it’s possible you’ll be told to “take it offline.”

It is to these people that many writers and filmmakers will be entrusting their work. These are the people who will privilege sport and mainstream computer games over the arts because the stats tell them to. If you’re lucky enough to find decent arts listings on a commercial website, it’ll be a personal indulgence on the part of the producer who runs it.

Further up the food chain, however, are the heavyweights. The ones glamorised by IBM advertisements. Old tie private schoolboys, ex-lawyers, ex-traditional media and too bright MBA grads who, come lately or by right of birth, subscribe to the old capitalist school of dress and behaviour; they wear suits (jeans are allowed on Fridays, providing they don’t have a meeting with the Telstra guys), make or tastefully ignore sexist jokes and earn a shitload of money for the privilege. Despite the recent dotcom ‘adjustment’ on the NASDAQ, these people still command salaries that start at 140k (even without equity) and just keep on getting higher. A polyglot of marketing executives, business strategists, e-commerce directors, CEOs and managing directors, these are the people who hold the purse strings. They are the people responsible for encouraging the syndication of content (ie that stuff we used to call editorial —the stuff it simply doesn’t make sense to produce in-house) across as many portals (the gateway to the rest of an internet network) as possible, to whom the term “media saturation” is freely interchangeable with “cost-effective.”

These are the people responsible for the hype surrounding convergence, who are currently shaping the “content” landscape on the web, setting the precedent for the licensing of short films from artists at rip-off rates, readily getting rid of web pages that aren’t paying for themselves. These are the people who are excited by the prospect of an internet/interactive TV/broadband (expensive, fast access to the net) environment by which your capacity to surf is limited to the content the corporation owns.

Despite what the Information Technology (a strange misnomer if ever there were one) sections of newspapers would have you believe, convergence is a fair way off becoming a digital reality for most people. But by the time it is, getting the right kind of money from a web company who wants to appear credible by licensing your film, might be nigh impossible. Looking to your interactive TV for inspiring content will feel strangely similar to subscribing to cable TV. Only instead of there being 200 channels of rehashed crap, there will be thousands of sites shoving crass advertorial and e-commerce opportunities down your throat—and the 9 rebranded corporations that used to form Microsoft will have a finger in most of them. We’ll look back with consumerist nostalgia to the time when advertising was actually distinguishable from the television show itself.

Maybe when the Coalition is voted out there will be more government subsidies and new media grants to ensure that interesting sites are built and web events take place. And hopefully, some of those projects will use the medium to critique the medium.

And hopefully most of us won’t be sucked in by a website funded by a bank whose spuriously deconstructive sociopolitical agenda—or is it an advertising campaign?—is to “unlearn.”

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 25

© Nadine Clements; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

You’re the cutest thing that I ever did see/really luv your peaches wanna shake your tree/Lovey dovey, lovey dovey, lovey dovey all the time/Oooey baby I sure show you a good time.

You’re the cutest thing that I ever did see/really luv your peaches wanna shake your tree/Lovey dovey, lovey dovey, lovey dovey all the time/Oooey baby I sure show you a good time.

Er, sorry about that. Don’t know what’s wrong with me today. Must be that email I just got from Peaches. I mean seriously, do you know anyone called Peaches? What about Buck, heard from him lately? Unlikely as it may sound, this nomenclature resonates with literary gravitas and the portent of tele-communications historiography. Stay with me.

Since McLuhan’s observation that new technologies are always inscribed by earlier modes and practices, media theory has insisted that its forms do not arrive unheralded. Cybercultural genealogy is awash with theorists peering further and further into the past. Commentators such as Margaret Wertheim (The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A history of space from Dante to the Internet, Doubleday, Sydney, 1999) argue that the idea of cyberspace is unthinkable without critiquing the changing metaphysical and scientific conceptions of space, and writers like Janet Abbate (Inventing the Internet, MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, 1999) or Katie Hafner and Matthew Lyon (Where Wizards Stay Up Late: the Origins of the Internet, Touchstone, New York 1996) dispute the conventional myth that the internet’s origins are limited to American military scenarios. But as these areas of inquiry are comprehensively covered, others remain somewhat under researched.

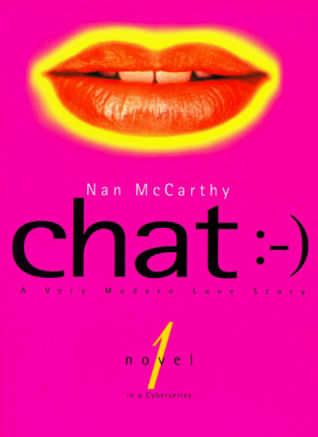

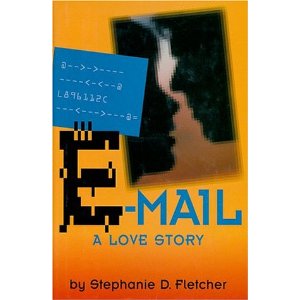

Electronic mail, while implicit in the cited studies, seems not to receive the same sort of sustained critique. One way to redress the gap is to historicise the email novel. This emerging genre can be traced to 18th century British and European cultures where an increasingly literate population and the technological advancements of the postal service give rise to the epistolary novel. Works such as Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos, Jean Jacques Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Heloise or Samuel Richardson’s Pamela are narratives constructed from letters whose formal and thematic properties presage certain contemporary literary genres.

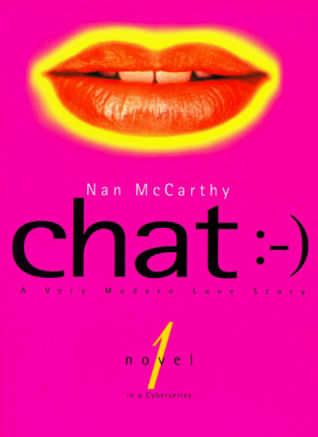

How to spot an email novel? Well, the title must include technological form, literary vehicle and a signifier of lerv. Cyber word, colon: love word. Consider, Chat: a cybernovel (Nan McCarthy, Peachpit Press, Berkeley 1996); Virtual Love: a novel (Simon & Schuster, New York 1994.); Safe Sex: An e-mail romance (Linda Burgess & Stephen Stratford, Godwit Publishing Limited, Auckland 1997); and Email: a love story (Stephanie D Fletcher, Headline Book Publishing, London 1996) and you begin to see the point. To a large extent, email novels function according to the generic principles of epistolary fiction. The exchanges are presented chronologically, framed by dates, salutations and signatures. In both genres there is a strong emphasis on the body’s absence: correspondents are separated spatially and temporally and the missive is used as a means to negotiate this gap. And both narratives are informed by themes of love, seduction, adultery and betrayal. More specifically, one might draw parallels between 2 of the texts by comparing their articulations of subjectivity formation.

Both the 18th century epistolary novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses and Fletcher’s E-Mail: A Love Story, for example, wrestle with the problem of women’s sexuality in terms of the transgression of institutional ideology. Laclos’ Mme de Merteuil is exiled because she dares to usurp the masculine privilege of the sexual aggressor and Katherine Simmons, the protagonist of E-Mail: A Love Story, is reformed at the novel’s end by her return to legitimate sexual acts defined by the marital contract. The configuration of identity seems to concern both genres since the epistle form permits an opportunity to explore or radicalise questions of subject formation. Mme de Merteuil explicitly refers to her propensity for dissembling and reinventing herself and the correspondents in Fletcher’s text regularly discuss the advantages of and need for the use of pseudonyms (hence “Peaches” and “Your cowboy, Buck”).

Both the 18th century epistolary novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses and Fletcher’s E-Mail: A Love Story, for example, wrestle with the problem of women’s sexuality in terms of the transgression of institutional ideology. Laclos’ Mme de Merteuil is exiled because she dares to usurp the masculine privilege of the sexual aggressor and Katherine Simmons, the protagonist of E-Mail: A Love Story, is reformed at the novel’s end by her return to legitimate sexual acts defined by the marital contract. The configuration of identity seems to concern both genres since the epistle form permits an opportunity to explore or radicalise questions of subject formation. Mme de Merteuil explicitly refers to her propensity for dissembling and reinventing herself and the correspondents in Fletcher’s text regularly discuss the advantages of and need for the use of pseudonyms (hence “Peaches” and “Your cowboy, Buck”).

While the 2 genres share some formal and thematic elements, there are of course points of departure. Part of the problem is to do with the awkward mimetic situation of email novels because they use the conventions of print technology to describe, represent and invoke the tropes of electronic communication. Email novels quote the digital sign. In place of the usual epistolary preface, E-mail a love story begins with 3 pages that reproduce the instructions for a fictitious computer based communications system called ‘Luxnet’ (based presumably on services such as America On Line or CompuServe): “to learn more about electronic mail simply click your mouse over the mail icon on the screen.” Needless to say, there is no mouse, icon or screen.

This mimetic fissure is tackled by Carl Steadman in a fascinating internet based project called Two Solitudes, an e-mail romance (http://www.freedonia.com/ – link expired). Steadman (one of the co-founders of Suck) has written a novel dictated by the email interface rather than the print environment. One ‘subscribes’ to the story using similar protocols to Listserv discussion groups. What follows is a series of emails purported to be copies of the correspondence from the exchanges of 2 people of indeterminate gender (Lane and Dana) but amorous intent. The technological verisimilitude is so successful that it is quite possible to forget one is reading fake mail. It is a compelling literary experiment clearly informed by the epistolary theory of Jacques Derrida’s The Post Card (1987).

Where Steadman’s theoretically astute email fiction is overtly indebted to an epistolary past (and all that that implies about the author/reader dynamic of tele-communication), the email novels must also be seen within their literary heritage. Just because someone in Email: A Love Story signs his missives from a ‘cyber Romeo’, doesn’t mean he can’t grow up to be John Malkovich.

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 27

© Esther Milne; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Linda Dement, In My Gash

It was but 6 years ago that the first works on CD-ROM by artists made their appearance, only 5 since the initial net art sites emerged. The rapid expansion of artists’ sites in the last 2 years has eclipsed and diminished the desire to place work onto CD. The considerable range of skills needed to make an interactive CD-ROM and then distribute it have kept artists’ attention on the improving quality and range of options available online—faster access times; browser and production software adapting to the desire for sound and movement; and an on tap means for delivering curated exhibitions to the audience (no freight, no installation, no need for a sustained level of funding).

Moving out of the notional centre (from the confined spaces of the gallery, from the vicissitudes of curatorial taste) into the digital highways and byways of cyberspace is becoming challenged, a la revenant, by the laneways and streetscapes of the analogue city. Drive by was a series of shop window projection installations by the Retarded Eye group for the Perth 2000 International Festival. (See RealTime 37, page 18). One of the works A throw of the dice (can never abolish chance) was made by Vikki Wilson with performer/writer Erin Hefferon as “an experiment in electronic writing to produce a work that makes a ‘movie’ on the fly with text, sound and video. The ‘movie’ is recognisably the same story but different in each version: a series of compressed serial-killer narratives—Perth-dwellers have been living with this story for some time.” The work reiterates its storylines, building a collage of permutations over time and was developed from a narrative database engine (made by Cam Merton of Retarded Eye), holding movies, sounds and sentences scripted to combine into narrative sequences as the engine runs. A DVD delivered the piece to the projector installation and is accessible on the web (http://arc.imago.com.au/ driveby), indicating an inexorable movement by this group and a few others overseas towards forms of online cinema.

As a work distributed on videotape, Love Hotel anticipates these shifts, summarising in 7 minutes of linear exposition the impact of online culture and communities on gender politics. Linda Wallace (www.machinehunger.com.au) takes video collected from Japan and New York and layers it in windows and boxes containing the words of Puppet Mistress (Francesca da Rimini reading excerpts from Fleshmeat, her forthcoming anthology, www.thing.net/~dollyoko), vectoring meanings from the collisions of resulting images. Screened recently as part of d>art00, the project adopts the provisional location of the love hotel to materialise in the media guises of cinema, television, multimedia, internet and next…gallery installation?

Rosalind Brodsky in her time travelling costumes spans right across the 20th century and into 2058, the year of her demise. The space she occupies during this bungy-jump is, of course, the virtual space of the interactive multimedia computer and the encounter between each user and the rich imagination of the artist…No Other Symptoms—Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky. Rosalind (the alter ego of the CD-ROM’s maker Suzanne Treister, see RealTime 34) delivers a monologue that ranges across late 20th century media studies discussion points from psychoanalysis to Mary Poppins, vibrators, sci-fi films, the Russian Revolution (complete with clips from Eisenstein’s October), 60s euphoria and hope for the future. Stories of Old Europe—pogroms, revolts, émigrés—are encountered. They are central to her history. Rosalind wishes to be “…connected to (her) roots…” and interspersed are photos and videos of the Treister family members, as family and as players in re-enactments of historical moments and encounters with extensive figments of Freud, Jung, Klein, Lacan and Kristeva. Rosalind as a time traveller is able, of course, to warn Freud to leave for London…he does. She sees a lot more of him. And so can we…

Lisa Roberts time travels via the simple action of turning the hands of a clock backwards and forwards (I discovered eventually this had to be performed quite vigorously), until entry is given to the labyrinths of the CD-ROM Terra Incognita. The smoke and mirror possibilities of the authoring tool Director (in spite of inexorable pixel-dissolves) recreated the séance-like atmosphere of the magic lantern, with static images from the artist’s experienced pencil and paint gestures flickering through parts of the writer Carmel Bird’s fiction, the images forming “the basis for an interactive ‘map’ of the creative process” perceived by the artist in response to the writer’s work. This is the work of a mature artist picking up and learning a complex multimedia tool.

Juvenate, from the Perth team of Michelle Glaser, Andrew Hutchison and Marie-Louise Xavier, also explores intersections of memory—“The beginning and the end reach out their hands to each other.” The simple action of rolling over unmarked parts of the images stimulates sounds and successive images to emerge in a flow of snapshot and watercolour elements constructed around the domestic. Abrasions, lesions and drips intervene into the sound of children’s voices as the user moves through the 36 scenes following a route that can be re-visited once learnt.

Linda Dement has recently completed her third CD-ROM, In My Gash. Like the earlier works, she creates a gentle correspondence between the user and the complex representations seen and heard, that in spite of the implication and threat of violence witnessed gives access through a real engagement to comprehension rather than the dead-end of the hopeless and intractable. As Anna Munster has observed: “Dement’s 3D animated renderings of gashes seemingly offer up representations of the mysterious leap from the physical to the psychical, from the outside to the inside, from the beautiful to the grotesque that straddle our understanding of gender relations (Photofile 60, forthcoming).”

TellTale is the flipside CD-ROM, “a mixture of sweetness, courage, nauseating patheticness and romance” in the words of its creator, Rebecca Bryant. As an immersion into the world of a soapie-like group of ‘characters in situations’, it enables the user to terminate irksome storylines, back into a more promising combination of plotline options and when all else fails, simply read scurrilous footnotes about members of the cast. Whilst navigation is elegantly designed and effected, the flux that personifies the notion of the soapie is placed into a state of fixity when delivered as a CD-ROM. Internet narrative possibilities have advanced this option more recently, utilising streamlined vector graphics which, when coupled with graphic images of the kind in TellTale, simulate a cinematic experience. (Jonni Nitro at www.eruptor.com and Too Hot at www.toohot.com are examples of the form if not the content).

The use of the 360 degree virtual space linked via rollovers to movies and graphic sequences enables discrete narratives to be coordinated into the virtual installation of Cross Currents by Dennis Del Favero, investigating the sex slave trade of Western Europe (see RealTime 34), or the encyclopedic Lore of the Land from Fraynework Multimedia. A big budget project involving Indigenous and non-indigenous Australians mostly in Victoria, the multi-faceted chapters examine history, ecology, culture, law and land with an approach that encourages the upkeep of an integrated personal journal of the user’s journey through the work, collecting images and notes along the way. A curious game of Discovery is incorporated (separately authored by Troy Innocent) which involves collecting artefacts from an uninhabited cave, egged on by an off-screen Aboriginal voice, before returning them to the ground. The goal of all this earnest activity is to move towards understanding, and the achievement of, reconciliation. The navigation system whilst easy to use keeps this rich resource at arm’s length relying, like a television doco, on the personalities of the individual contributors to provide the spirit of the piece. The outcomes of individual journals linked through a website forum (www.loreoftheland.com.au) potentially close the gap between the user and the experience and process of assimilating this work.

User confidence is challenged in the elegant Electronic Sound Remixers by Tobias Kazumichi Grime, where the ubiquitous Director authoring tool enables the user to combine from a palette of attractive sounds a mix using a design grid with an attractive variety of visual slider devices. Is the mix actual or, as the user begins to suspect, the result of options only partially given by the author?

Virtual kitchens were a factor in the mix of the year’s completed works. Dream Kitchen by Leon Cmielewski and Josephine Starrs submerges us beneath the smooth surfaces of the domestic laboratory to examine its seams and what lies hidden: fire-raising pencils and pens, anthropomorphised garbage, an opportunity to take the Interface Test and apply an increasing electrical voltage to a dead frog. Witnessing from a surveillance position behind the phone the S&M goings-on of the otherwise absent owners adds spice to this ingenious wunderküchekabinet. Michael Buckley’s Good Cook dives beneath the psychic surfaces of the professional kitchen during a sleepless night for the chef. The user shares his frustration at not being able to shake off meandering thought and image recollections as the mouse threads our way from the trials of the previous night’s work to childhood memories and the paternal pathways of songs and scriptures.

Delivered after a short gestation, the pixel, the byte and the inkjet are seamlessly integrated via the CCD and the chip into a contemporary practice that is again dissolving the artificial barriers to the possible erected by corporate culture and the ambitions of software engineers. Time-based technologies used to ‘fix light to a time signature’ are in ever more constant flux, again redefining the terms of hybridity, again continuing the development trajectory of the newer media within screen culture.

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 6

© Mike Leggett; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Drawing as it does on rapidly changing technology, electronic art is always looking out for the next wave, a new process, a new platform. As the technology industries continue to generate novelty—a mixture of promises and products—at a breathtaking rate, artists adopt and adapt both the rhetoric and the technology, slipstreaming behind the biggest, fastest juggernaut around.

So in the year when, as a child, I imagined the future would finally arrive, there is an interesting, subtle sense of pressure on the electronic arts—as if they too should be finally ‘arriving,’ coming up with the goods, delivering on their promises and aspirations, breaking into the mainstream. At the same time, the status of the electronic arts is undergoing perhaps its most serious challenge—because the future is arriving, in a straightforward, quotidian way, but it’s arriving all over the place, indiscriminately and without regard for who’s been waiting the longest. Here I want to discuss that challenge, and show how it may ultimately—in fact hopefully—bring about the end of ‘electronic art,’ ‘digital art’ and ‘new media art’ as they currently exist.

This challenge arises quietly, as a particular threshold is crossed—a threshold of technological saturation. Over the past decade, high-tech (and specifically digital) media forms have proliferated to the point of being ubiquitous in our everyday lives. Almost every manufactured image that we see—every laser-printed flyer taped to a pole, every book jacket, every billboard, every TV ad—is now a high-tech artefact, a product of layers of digital processing and production. Film, a uniquely persistent analogue medium, is embracing digital production. An overwhelming majority of the audio which we encounter is ‘digital’—at least in its means of reproduction, though increasingly in its creation as well. At the same time, ‘new’ media forms (email, the web, console games, mobile phones) are threading themselves ever more tightly into everyday life.

A couple of years ago a new Coles supermarket opened in my neighbourhood, complete with an array of beautiful, flat LCD touchscreens which function as cash registers and point-of-sale advertising displays. When I first saw those screens, I was struck by their potential; I imagined somehow appropriating them for a lavish interactive artwork. They looked so incongruous; precious technological artefacts surrounded by racks of chewing gum and magazines. At some point since then, though, the screens changed: the supermarket assimilated them; now I just see cash registers with banner ads.

The saturation of our lives, and our culture, in media technology, is predictable enough; the process has been clearly underway for decades. What’s more interesting here—and what the supermarket story illustrates—is that this process has finally reached a point where these media technologies are completely unremarkable. The ‘digital-ness’ of a CD simply doesn’t matter (any more); nor does the fact that the titles for the evening news are computer-generated, or that this publication is digitally typeset. Even where the technology itself is unavoidable, the rhetoric around it now concentrates on basic utility value: the commercial, consumer web packages itself as a lifestyle-enhancer, a time-saver, an appliance, but never as a technology.

This process of disappearance or dissolution is facilitated by the increasing sophistication of digital media technologies. This is clear in Hollywood cinema where digital technique is crossing a corresponding threshold of perception; nobody remembers the computer graphics in Saving Private Ryan. Contrast this with the self-referential graphics of 10 or 20 years ago; remember the opening titles to the first series of Towards 2000? Glowing wireframe jet planes and spacecraft zoom out of the screen. The message was clear: “the future is technology, and it’s coming right for you.” Now that we’re here, the glowing wireframe is a retro icon for a simpler time. Contemporary media technology is a shape-shifter—it puts on the skins of forms it’s killed (film grain filters, lens flare effects, vinyl crackle plug-ins)—but can look and sound like anything, or nothing.

What does this shift mean for the electronic or ‘new media’ arts? In one sense, it means almost nothing, or rather, more of the same. As media technologies become more sophisticated and more accessible, the arts benefit; more room for experimentation and play, more potential, more power, more scope. These have always been the payoffs for riding with the technology juggernaut. In another sense however, this shift represents a significant challenge to the ways in which the high-tech arts construct and identify themselves.

Sparked perhaps by the reluctance of the established art-world to accept their work, artists using electronic media have gathered, over the past 2 decades, under such generic banners as ‘electronic art,’ ‘digital art,’ and ‘new media art.’ An active international scene has emerged, with its own institutions, events, stars, critics, and gossip, all organised around a common creative engagement with technology. This identification with a technological medium has been useful in many ways: technology is a drawcard, a (largely) positive cultural marker, often attractive to the powers that be. While often highly critical of its technologies of choice, electronic art has also been happy to borrow the progressive rhetorics of ‘cutting edge’ technoculture for self-promotional purposes.

That rhetoric only works, though, when the technologies involved are new and exotic, and digital media are no longer either of those things. Where does this leave (not-so-) new media art? Those with a hankering for the experimental will no doubt continue to seek out esoteric and emerging technologies; biotech art is already a reality, no doubt nanotech art is close at hand. Having been crowded out of digital media, the high-tech avant-garde might simply move elsewhere. However there is another option which is more radical, but also more interesting: what if artists working with technology stopped identifying their practice as ‘new media art’ or ‘digital art’? How useful are these designators in a culture in which digital media are the ascendant status quo? What if the technology-based banners for this field were simply taken down, now that their age is starting to show?

Suppose for a moment that this were possible, and imagine the consequences. It might demonstrate that these generic labels have never been a useful way of thinking about, or engaging with, this practice. They lump a diverse range of work into a category which ignores the most interesting aspects of the work—its content—and concentrates on a set of technical and production processes. If that category were to dissolve—as it is dissolving in culture at large—we might find a more complex way of thinking about this work. All those clusters of shared values, approaches and aesthetics which already exist within new media practice would come to the fore—those groupings would be recognised, rather than subsumed. At the same time, the networks of trans-disciplinary influence and continuity which already run across the field would develop. These banners involve an act of differentiation, a declaration of a separate practice—yet among the richest zones are those where electronic media meet existing creative and discursive traditions.

The notion of ‘new media’ as some kind of radical move and/or critical problem will, with any luck, recede. That hoary old excuse for the uneven quality of new media practice—that it’s ‘early days’, and that ‘in X years we’ll look back on this as the beginning of a new era’—will go with it. More space and energy will be left for a real engagement with the work, in all its cultural and creative specificity. Of course this is not to propose that the media themselves should be ignored, either by artists or critics. The process of grappling with the medium is part of doing creative work, just as the process of deconstructing, interrogating and analysing those media is part of critical work. In rapidly-changing domains such as the web, these processes are crucial, and certainly net.art plays an ever-more-essential role in offering alternative ways of thinking through that medium. Still, there’s more to it than that.

What about those organisations structured around medium-specific banners? What of the funding bodies, who play an important role in the construction of those categories of practice? Without the banners of ‘new media’ or ‘digital art,’ and the sense of solidarity and legitimacy which they bring with them, artists may find it even more difficult to gain support for their work. It’s these (important) pragmatics which will most likely ensure that this thought-experiment is never realised. Take it instead as a wistful vision; a sprawling continuum where high- and low-tech art co-exist and intermingle. Or better, a polemical jolt, a hypothetical. Either way, the wider process which sparked it is obstinately real; the ‘new media’ are becoming everyday, unremarkable, imperceptible, ubiquitous—and they won’t be new for long. Similarly, the best thing that could happen to ‘new media art’ would be for it to dissolve—not vanish, but dissolve—and for the medium to give way to the work.

This article is a variation of a talk given at the Being Digital forum, chaired by Susan Charlton and organised by dLux media arts, as part of the Sydney Film Festival, Dendy Martin Place, Sydney June 15.

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 7

© Mitchell Whitelaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tatiana Pentes, Strange Cities

Apart, of course, from C3PO’s nervy variation on the loyal poof valet, the best thing about Star Wars (Mach I) was all those twee segues: the windscreen-wiper, the venetian-blind, the diagonal swipe, the horizontal shutter…later zombied back to life in PowerPoint.

In spite of the vistas opened by hyperlinks, much writing for multimedia—and especially for the web—never quite manages decent textual segues, something narrative or perspectival or dialogic that can ease or direct the wormhole transition between nodes. All too often instead you get chunked, clunky Lego blocks of text-as-data and interfaces standing in for connections. Not with these projects.

Tatiana Pentes’ Strange Cities CD-ROM takes the segue and transposes it to a musical idiom that originates in, reconfigures and encases the unbelievable story of her grandparents, who were serial refugees and always-already aliens or exoticised expatriates.

The frame-story is told by the narrator, Sasha, who didn’t believe all their outlandish tales until, after their death, she was about to incinerate a box of old memorabilia from Sergei and Xenia Ermolaeff. We open that box ourselves, and follow the sepia photos and ID papers back to Russia, to the Bolshevik Revolution, escape to China, the marriage in Tianjin, Shanghai’s polyglot immigrant community, the decadent jazz clubs Sergei’s band played, rubbing tuxedo-ed shoulders with Chiang Kai-shek and Charlie Chaplin, Xenia becoming a glamorous nightclub dancer, Mao’s revolution, asylum in Australia and suddenly 50s anti-Reds paranoia, the claustrophobic suburbanality of permanent nostalgia. In and out of frame, as intro and closure, move press clippings, an evocative layered-n-textured Photoshop-ad’s-worth of old photos, creaky newsreels and retooled recent footage, Trotsky speeches, Sergei’s songs and the band’s smoky jazz, contemporary radio broadcasts, un-artificial soundscapes, and narratorial voiceovers.

The effect is that of stretto, the fugue technique of overlapping and entangling voices and time signatures, where Pentes eschews the pull of Hollywoodising the admittedly-amazing story into linear cinematic re-telling, so it’s less trajectory than transitional vignettes. These are composed as ‘movements’—Prima Volta, Mordente and Lacrimoso—with multiple interfaces, menus, image-maps, differentiated mouse-pointer icons and situational identifying soundtracks. Pentes has exploited the ways in which expressive multimedia can parallel the modes, feel and mechanisms of memory-in-anecdote to memorialise her grandparents’ lives in a work that at last makes musical structural metaphors something more than a branding exercise.

Los Dias y las Noches de Los Muertos (The Days and Nights of the Dead), a website from Francesca da Rimini (www.thing.net/~dollyoko/LOSDIAS/INDEX.HTML) with sound by Mikey Grimm and grafix and translations from a big gaggle of collaborators, is virtually nothing but segue, contracted to such a hyperkinetic attack it strafes you. Step 1: download the soundtrack and get its stripped industrial-electronica going. Step 2: um, that’s someone crying isn’t it? & someone screaming…moaning—disconsolate sobs and it sounds like—& feels like—torture…weird how I’m kicked out of viewer-ly complacency by war’s fallout coming tinnily from my tiny speakers. Step 3: “click to start”, a disingenuously clichéd invitation that ends up spawning a new window, ambushing my browser to set off a series of graphical and plain-text detonations.

It’s all auto-refreshing, webpages replaced automatically by another without a mouse-click. Try clicking and you just get more 3-second-delay transitions. We’re talking hypertext-as-70s-zapping in Greenaway split-screen TV here, 5 frames vertiginously kaleidoscoping between quotations from Napoleon on the art of war, press stuff from the Zapatistas, excerpts from the US Space Command’s ‘Vision 2000’ policy (terrifyingly vacuous…but remember Reagan’s ‘Star Wars’?), Machiavellian directives for netwar and a slew of snippets posing as ICQ Logs strobing you in Exhibit-A flashes. In a kind of striking narrativisation of the Seattle WTO protest, globalising multinational capitalism is made to lip-synch the motives and pragmatics of war. So you get, for instance, EXXON announcing “death is nothing; but to live vanquished and without glory is to die every day”; or The Vatican Bank, or Shell, or Coca Cola, philosophising on battle. For anyone who’s followed the harrowing online media accounts, the visceral experiences and pleas of the Zapatistas, colliding—often almost literally—with the blandly glib, spin-doctored policy statements on war and the vortex of imagery…it’s wrenching.

Similarly disturbing, but uncannily, is Whoseland.com, an “inter@ctive documentary” (it’s 2000: let’s declare a moratorium on @) about the 1998 Africa-Australia Exchange on Land Rights for the Millennium (www.whoseland.com). It reads, from Howard’s (un)sorry 2000 state of affairs, as an uncanny present-tense palimpsest of connections made and missed, hopes now boxed-up in apathy, and a productive international effort at recompense, equity, practical solutions and modest proposals. It generates its momentum from chronology: the inception of the project, its main press conferences (one by Ben Elton at his ratbag best), the experiences of the delegates from Maasai and Barabaig peoples in Australia and of the Kimberley Land Council in Africa, the 1998 Melbourne protest march, heading towards the Centenary Celebrations in 2000. Each section’s colour-coded, crystallised in a spiral site-map and navigable by elegant icons, backed by extensive content varying from first-person accounts to full transcripts, a click-zoom-able map of tribal ownership and languages, and a useful collection of research papers.

The writing is taut and engaging throughout, exploiting the narrative drive and delegates’ excitement, heavily and effectively illustrated by photos and vox-pop videos. Return exchange visits were planned for 1999 but—and this is more than the usual existential whinge—although the site promises to provide updated content up to 2000, it peters out at 1999, exacerbating the cross-wired time perspectives.

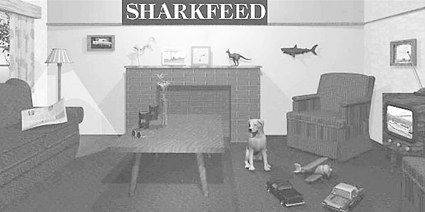

Sharkfeed, by John Grech and Matthew Leonard (www.abc.net.au/ sharkfeed /index.htm – expired; see RealTime/ OnScreen 38), extends such cross-wiring by looping round a 1960 kidnapping-murder case, and literalises it in ‘rephotography’, which makes a refrain out of re-framing photos with the same subject over disparate time and place locations. In June 1960 the Thorne family from Bondi won the Opera House Lottery (100,000 pounds!), which led to their son Graeme being kidnapped by Stephen Lesley Bradley (Istvan Baranjoy), a migrant Jewish-Hungarian WWII survivor, for a ransom. Graeme died, probably inadvertently but horribly nonetheless on the day of the kidnapping.

As with Strange Cities, the project is in focal flux from the main storyline outwards, bricolaging an album of traces from archival footage, old news media photos, recordings, interview/broadcast transcripts, sound files (from Paul Robeson singing in Sydney to the Police Commissioner’s briefings), headlines, reconstructed evidence snapshots, sketches, photo montages, mixed-time-period panoramas, and crime-scene maps.

The project’s creators explore the way the Thorne case inaugurated the long history of sensationalist quickie-trash true-crime books, yet Sharkfeed regularly falls into the same exploitative formulae, like: “Graeme Thorne was kidnapped on the way to school, a journey from which he never returned. Afterwards, nothing was quite the same again.” Um, yes. Etc. The main navigation option (‘continue’ or ‘about’ as rollovers) is not exactly aesthetically or hypertextually exciting, but you also get regular ‘detour’ possibilities, a nice-if-superfluous VRML interface, and category menus; but it’s the transitions that rescue it from TV-re-enactment, circling round from the compelling narrative-doco and true-crime-voyeur arcs into the wider disturbing social issues. Sure, it leads to some questionable philosophising—“as the lives of all those children were lost, they began another kind of life, in a mythical space from which they can never escape”—and gratuitous puns on ‘corpus’, but it’ll absorb you and make you think, get you arguing and where’s your kid right now?

In contrast to the centripetal pull of a main storyline, Archiving Imagination (www.archiving. com.au/archiving/index.html) is an unapologetically disparate sampler of collaborations between Robin Petterd (digital media artist) and Diane Caney (writer/web-author and editor of the Australian Humanities Review). Most of the works are brief and concentrated, surreal or haiku-ish poetic writing dramatised by video or made into rhythmical movements by minimal design, braided hyperlink arcs, discrete sound effects, muted terrace-house colour schemes and a beautiful line in fade-in-fade-out gif animations lushly mirroring the lyrical text…“and when I sleep my mind bathes in the memory of your skin.” Often coyly unpredictable or navigationally unclear, the design forces cursor exploration: rollovers, image-maps, auto-opening links and floating windows are all used to pointed textual effect with surprises and hidden sections. And the writing itself, to which the focus always returns, is worth the hunt and the wait.

Alyssa Rothwell’s From My Porch CD-ROM is three-in-one: Three Mile Creek, Getting Dollied Up and Pretty Aprons. The first 2 have only minimal writing components, so I won’t cover them here. But Pretty Aprons! An absolute bloody gem, as its characters, or my ex-country-town Dad, would say. After some exquisite time-lapse sand animations, you’re suddenly in front of a sketched old pedal-powered Singer sewing machine, a basket of cloth by your feet, teacup on the edge. You’re on a farm, making aprons for Xmas gifts. Drag your cloth onto the Singer and fragments from sewing patterns or recipes or a faded women’s magazine slide onto the screen: assemble them and the stories start, rendered in miniature-insert sand animations or in beautiful pencil sketches featuring a character wearing something made from the cloth you chose. You can drop in on an old chatty neighbour for eggs and stay for a nice cuppa, which you pour yourself, setting off a tangle of yarns about everything from onions as a baldness cure to growing up a tomboy. At one point the teapot just won’t stop pouring and as the tide rises round the armchair you hear all about the ’54 flood. Then there’s the salesyard, the ballet lesson with the Mums sitting knitting but pirouetting inside, while a Prunella Scales voice harangues you “2,3,4…bottoms in THANK you”…but, oh, my favourite was the piano-practice, where you can either listen to someone practising (oops, wrong note) or play the piano yourself with the mouse (no, really). And if you stop playing for more than 5 seconds Mum querulously yells from the kitchen “Why’ve you stopped?!”

Each time you’ve had enough of a scene you can pull the pins out to return to the sewing machine and there’s another finished apron hanging on the line. A young girl works throughout as the narrator, encouraging you to finish another apron, telling tales on her Mum and her passion for sewing, how once, when the cat finally made a mistake in its acrobatic provocation of the dogs from its perch up on the water-tank, Mum came home to find its insides hanging out, so she took a small needle and some thin fishing line and sewed it back together on the verandah. To this day she wonders if she’d used a bigger needle or a different stitch it’d be walking without a Karloff twist. Funny, real, addictive. For the first time ever I wanna buy a CD-ROM and give it to friends as a present, better’n a book.

Now, naturally, having begun by pontificating about textual transitions, it’s become impossible for me to extricate myself by seguing gracefully to a neat close. So I won’t.

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 3

© Dean Kiley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Patricia Piccinini, Breathing Room