Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

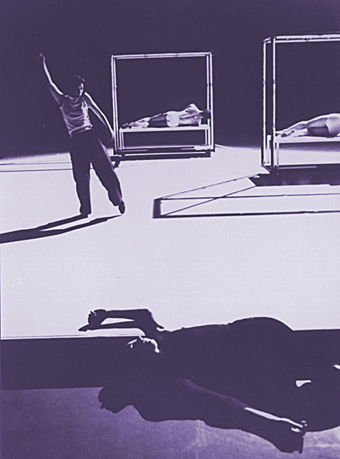

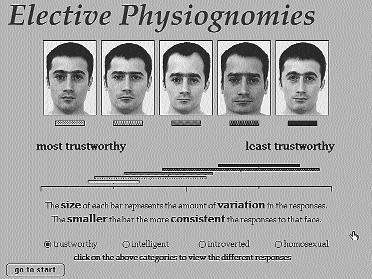

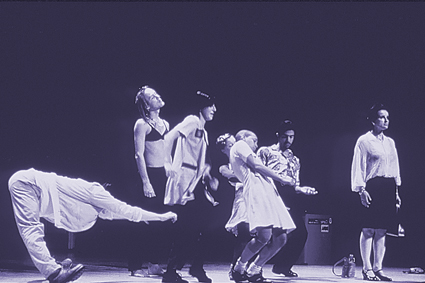

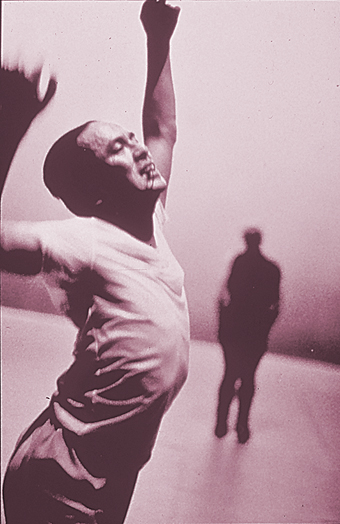

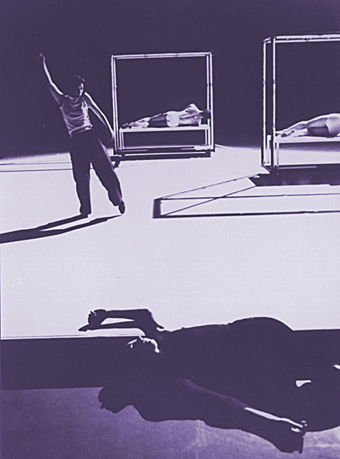

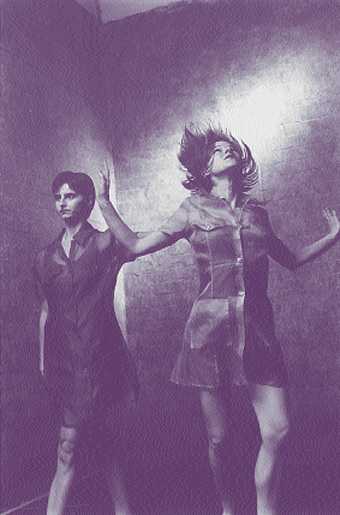

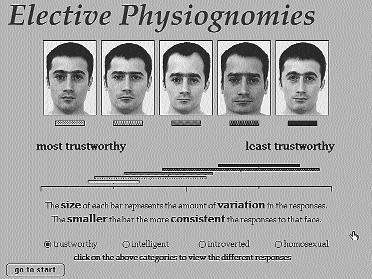

Retina Dance Company

photo Marc Hoflack

Retina Dance Company

The Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) used to be one of the most progressive live art venues in Britain, featuring international artists and nurturing national talent on the peripheries of performance culture. Inexplicably the programming department recently closed and the live art offer of this excellently resourced centre has dwindled to the ad hoc hire of space to visiting groups such as the Lust contingent who presented the multimedia festival, Strange Fruits, Nature’s Mutations, March 25-28. Links nevertheless remain between previous performance programming, current activity in the gallery, the cinematheque and media arts centre and externally curated events, for Lustfest mixed its media so thoroughly that that old ICA feeling of disorientation and sensory overload remained.

Lust are a cliquey London-based collective of multi-disciplined European artists, “umbilically linked by a network of creative relationships.” Founded in 1992, Lust has annually presented a showcase of experimental performance art with a plethora of premieres and an edgy degree of “it’ll be alright on the night” improvisation.

This year’s festival took advantage of the ICA Bar (regular host to DJs and projectionists) by presenting a series of eclectic musical partnerships to loosen up the punters for the main events in the theatre. On the opening night, Fabienne Audeoud and L’Orange screeched and swooned respectively, offering the A to Z of female vocal tactics to bewildered boozers. ICA members, in for a quick pre-commute pint, were hurried homeward by Audeoud’s operatic improvisations.

In the theatre, Malcolm Boyle’s one man Mission for the Millennium introduced the fearsome faith and fantasy of evangelical revivalist Reverend Anal Hornchurch. Bose and Ficarra’s experimental film last june-4.30am provided respite in its fuzzy evocation of fleeting internal landscapes and the German quintet, Obst Obscure, entered still shadowier realms with their ghostly Kino Concert, incorporating filmic imagery into a Kafka inspired soundscape.

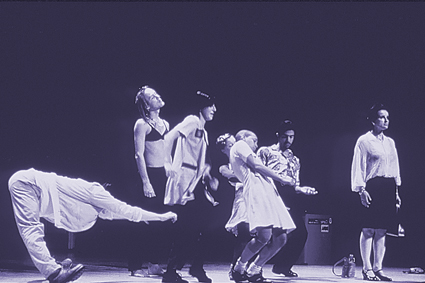

This same spaced out vibe coloured Thursday’s Trance Magic set by Polish vocalist/pianist/composer Jarmilia Xymena Gorna whose wild, echoey arpeggios bewitched the urbane drinkers. In the theatre Jane Chapman’s harpsichord found startling contemporary resonances, in dialogue with Daniel Biro’s Fender, Rhodes’ piano and Peter Lockett’s percussion. Two short films failed to impress amidst these sonic assaults and it was only the concluding performance of Tweeling by Retina Dance Company which reasserted the earlier intensity. Filip van Huffel and Sacha Lee’s demotic twins were all id as they forged the naked will to separate and dance their raw new selves into life. This act of creation, to Jules Maxwell’s evocative score, drew a cohesive conclusion to an epic evening.

Friday focused on a real-time ISDN linked jam with musicians in Nice, however a shamefaced Luc Martinez communicated the first anticlimax of the festival, announcing the failure of the video link. The audio connection to audiences and artists gathered at CIRM (Centre International pour Recherche de la Musique) left much to the imagination. As Martinez manipulated photo-sensitive instruments through a jazzy improvisation, it was unclear whether the intervening noises were his distant colleagues or simply another sample from his own computer. And yet the loss of raison d’etre did not entirely deflate this event as the bilingual apologies were followed by a ghostly, obscurely enchanting exchange with the ether. It is ironic that the much fanfared New Media Centre of the ICA cannot overcome an obstacle as concrete and foreseeable as the two incompatible national ISDN networks which undermined this event. Blame lies both with the venue’s lack of support for visiting artists and with the artists themselves, inadequately prepared, as ever, for the age-old technical hitch.

In more controlled circumstances, the festival drew to a close in the safe hands of saxophonist Evan Parker, in conversation with Lawrence Casserley’s diabolical deck of sound processors. Repeating her anomalous intervention with another disappointing dance/film, Jane Turner’s company presented Hybrid, a work as uninspiring as Friday’s solo, Compost, demonstrating that multiple media can confound artists and confuse audiences, with distracting results.

The enduring value of Lustfest, like most multimedia ventures, lies in its ambition. The disjunction between rhetoric and reality, ideals and outcomes, is typical of such progressive initiatives. Artists inspired by the multiple opportunities of cross-cultural, cross artform creativity, facilitated by new technologies will never be thorough or pragmatic. The outcome of all this abundance is almost by necessity erratic. Audiences, forearmed with tolerance, tempered expectations and a capacity to spot the golden needle in the haystack, will doubtless return to the ICA for Lustfest ’99, if either organisation remains.

Strange Fruits, Nature’s Mutations, Lust, Institute of Contemporary Art, London, March 25 – 28

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 14

© Sophie Hansen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

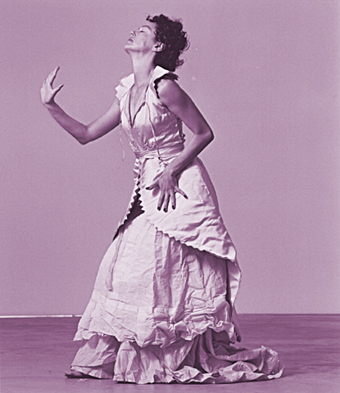

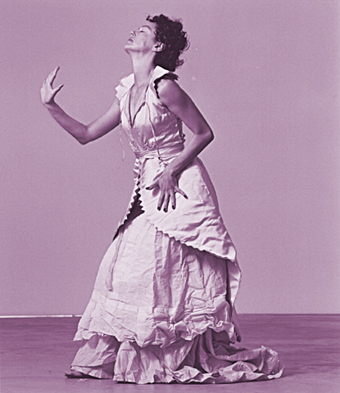

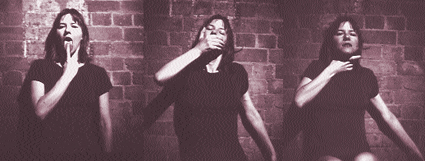

Ros Warby

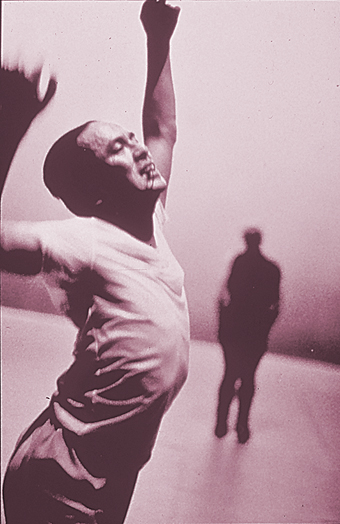

Sitting in the darkness, audience and performers alike wait for Ros Warby’s Enso to begin. We are forced to listen—to the rustles and coughs of others, whilst we open ourselves to the moment. Sometimes it is hard to identify an improvised work but listening is often one of its telltale signs. Enso moves between 3 performers, dancer (Ros Warby), cellist (Helen Mountfort) and singer (Jeannie Van de Velde). The flow of material throughout the piece is punctuated with spaces where each performer listens, waiting for each other to begin.

We are told that the structure of the work is set but that its content is open. There is a sense that the performers know who will begin a section. Eyes flicker towards Mountfort’s cello, ears strain towards Van de Velde’s voice, bodies lean to where Warby is waiting to move. But, and this is another of improvisation’s telltale signs, there is an episodic character to the flow of the piece. At one point, Warby’s movements are driven to the wall by Van de Valde’s vocal crescendo. Then a waiting for the next interaction to occur. A little later, Warby develops a most beautiful, intricate spinning motion across the room, then stops. More listening. A fan of Warby’s dancing, I want more from her. I don’t want her to wait for the others, to do nothing while allowing their contribution. But I have to accept the equity of the situation, its play between leading, listening, following, playing solo, making duets, forming trios.

There is scintillation to Warby’s movement, an exquisite attention to detail—the curlicue of her fingers, the twisted line of an arm—which speak of the moment. The attention permeating Warby’s body fills the most minute of spaces in a glorious detail; a dimly lit arm, curling and shaping itself, the length of a back spiralling into the turn of a head. One of Warby’s distinctive qualities is her ability to vary her speed with little apparent effort. Her work is textured by a subtle variety of velocities. A contemplation of fingers, wrist, and arm becomes a fast moving checkerboard of movement without notice.

Although set choreography can admit of any amount of depth and detail, there is a perceptual awareness which resonates in some improvisational work. One senses that the performer is utterly engaged in the moment, discovering and perceiving the work as it occurs. This distinguishes improvisation from set choreography, for the performer is making the work as it is being performed. Here, the performer, like audience, apprehends the unfolding of the work within the temporality of the performance itself. That makes for a certain degree of excitement.

Seasoned performers, Peter Trotman and Andrew Morrish, exploit that excitement for their own and other’s amusement. Their latest work, The Charlatan’s Web, is full of very funny moments where one performer invents a brazen complication which the other partner must incorporate. We the audience are invited to gloat over the sudden landscape which improvisation is able to thrust upon its subjects. The Charlatan’s Web was developed over 4 performances into an epic tale of character and intrigue. A man without qualities is banished from a religious cloister for the mortal sin of knowledge. He sails away to avoid execution, ultimately jumping ship in order to spin a web of chicanery and deceit. Andrew Morrish plays the hapless novice-cum-artful trickster, and Peter Trotman the feverish priest, who devours his books with a carnal lust.

The work begins with a duet, where Trotman and Morrish move simply from the back of the stage to the front. This enables them to establish a play of timing and rapport. Once established, the duo moves apart. A good deal of the tale is told by one performer moving and the other providing narrative, whether on stage or off. The work has a gem-like quality, of candle-lit cameos such as Trotman’s intense portrayal of the priest huddled over his books, sucking out their contents; the main character is himself a man of many faces; and the narrative just a series of fragments.

This is largely a play between word and movement. Neither performer exhibits a dancerly technique. Their panache comes from their energy and timing. They are utterly committed to their performance and to each other, such that the work as a whole and the contribution of each is seamless. I think the longevity of the Trotman-Morrish partnership—16 years—enables this duo to comfortably risk the narrative flow of their work for the greater good of the piece. Trotman and Morrish have just returned from the 1997 New York Improvisational Festival, where Deborah Jowitt of the Village Voice described them as “two extremely wily, full throttle performers whose nutty dancing and subtle timing elevate verbal wit into inspired madness” (December 1997).

Enso and The Charlatan’s Web are ultimately distinguished by the technical skills that each performer brings to the improvisational moment. Despite the indeterminacy of improvisation, the history of people’s work inevitably speaks though their performance. Though the work itself may be fresh, the skills that make it possible are not gained so easily. It seems like a contradiction in terms to prepare for improvisation, but it takes some dexterity to produce work which surprises even the body making it.

–

Enso, A Choreography between Movement and Sound, Ros Warby, Helen Mountfort, and Jeannie Van de Velde, Danceworks, Melbourne, March 27 – April 5; The Charlatan’s Web, Peter Trotman and Andrew Morrish, Dancehouse, Melbourne, March 29 – April 5

Philipa Rothfield is a Melbourne academic (Philosophy, La Trobe University) and sometime performer. Her next work, Logic, will be shown at Mixed Metaphor, Dancehouse, July 2 – 5

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 15

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

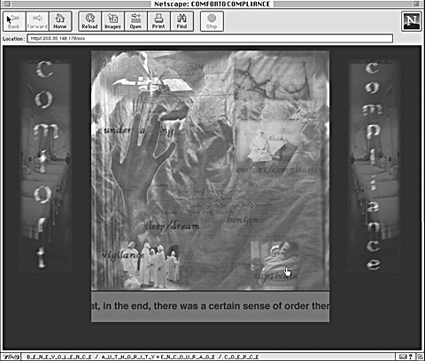

Dame Edith Cowan, Australia’s first female Parliamentarian, checks out Arts_Edge

Unusual to see an exhibition of web-based and CD-ROM work in a State collecting institution. Their particular digital obsession—not surprisingly—is digitisation of their various collections. So it was great to see Arts_Edge at the Art Gallery of WA in March, beautifully installed in the central atrium space of the gallery. It certainly found a very different kind of audience to that at your typical (sic) contemporary or screen-based art space/event: lots of school kids, families and senior citizens. The only problem I could discern, was to do with the number of stations and headsets available. It meant queues.

Arts_Edge was an integral component of Arts on the Edge, the conference on arts and education hosted by the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts, Edith Cowan University. Co-ordinated by Derek Kreckler from the Academy of Performing Arts, this project was developed with a particular commitment to the necessity of creating an archive of these kinds of works before their particular techno-historical and creative 15 minutes has passed.

The exhibition came with a $5,000 cash prize and an Apple computer donated by Westech Computers. The cash was divided between Sally Pryor (AUS) for Postcard from Tunis and Perry Hoberman (USA) for The Sub-Division of Electric Light. Francesca da Rimini and Michael Grimm (AUS) are still working out how to carve up the dual processor Apple 7220 awarded for dollspace.

A much smaller exhibition than, say, Burning the Interface or techne, it was great to actually feel you could spend time with the individual works without needing an entire lifetime to do so. Aside from the excellent winning entries, I particularly enjoyed Melinda Rackham’s Line (web-based) and Dieter Kiessling’s cute CD-ROM Continue, which suggests a parodic link to Minimalism and the Fluxus wit of the 60s and 70s. Rather than attempting to fool us into accepting the ‘false infinities’ that the hype around CD-ROM would have us believe in, Continue takes us to the other end—or perhaps the beginning—to the binary code degree zero. Continue and The Sub Division of Electric Light are just 2 of the works exhibited in the witty ZKM Artintact series (See John Conomos’ report on ZKM on page 28).

Many will be familiar with Canadian Luc Courchesne’s Portrait One also screened in Burning the Interface. Portrait One is a witty virtual dialogue between the viewer and a ‘slyly amicable girl.’ Image association determines Slippery Traces: The Postcard Trail, a collaboration between George Legrady (CAN) and Rosemary Comella (USA). The viewer navigates a maze of about 200 interconnected postcards, snapping on hot spots which take you to other images through literal, semiotic, psychoanalytic, metaphoric or other links. Speaking of slippery, Brad Miller and McKenzie Wark’s Planet of Noise occupied a machine of its own and chasing the hot spots to move through the ROM provided hours of family fun. Great graphics and sound.

A coherent and enjoyable exhibition with an excellent catalogue essay by the McKenzie Wark, an important outcome from this event is the archiving—by the WA Academy of Performing Arts—of all the works exhibited: 4 web-based and 10 CD-ROM works. The archive is intended to be developed over a 10 year period.

Exhibiting Artists: web works: Line, Melinda Rackham (AUS); The Error by John Duncan (Italy); Maintenance Web by Kevin and Jennifer McCoy and Torsten Burns (AUS); dollspace by Francesca da Rimini and Michael Grimm (AUS). CD-ROMs: Shock in the Ear by Norie Neumark (AUS); Slippery traces: the postcard trail by George Legrady (USA); Portrait One by Luc Courchesne (Canada); Manuscript by Eric Lanz (GER); Troubles with Sex, Theory and History by Marina Grzinic and Aina Smid (Slovenia); Cyber Underground Poetry by Komninos Zervos, (AUS); Postcards from Tunis by Sally Pryor (AUS); The Subdivision of Electric Light by Perry Hoberman (USA); Continue by Dieter Kiessling (Germany) and Planet of Noise by Brad Miler and McKenzie Wark (AUS).

Arts_Edge, coordinated by Derek Kreckler, Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts and Imago Multimedia Centre at the Art Gallery of WA, March 27 – April 8.

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 11

© Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

It is an unfortunate sign of the ironic times we live in that 21.C magazine won’t be ringing in the new millennium. The magazine of the future is to be discontinued after 7 fruitful years of projection and speculation, in which the technoculture that now seems so familiar was carefully mapped out and articulated. Its last issue, “Revolting America”, edited by R.U. Sirius and prophetically subtitled “No Future”, is the magazine’s reluctant swansong, signalling, after Baudrillard, that in at least one incarnation the 3rd millennium has indeed already come and gone.

21.C had many qualities that made it distinctive. Its variety and unpredictability made it difficult to identify any singular contribution to the accelerated countdown to the future that has become so rampant in the last decade of the 20th century. However its determination to cross all checkpoints was in fact the quality that made it stand out from the crowd. 21.C was less pretentious and fashion conscious than Mondo 2000 and much broader in its scope than Wired. It recognized that the contemporary world was multi-faceted and fuzzy, a poetic body sans organs, as dependent as ever upon all areas of pre-digital cultural production. Unlike other publications attending to the trajectories of the present into the future, 21.C recognized the importance of cultural memory as well, and did its best to tease out its traces and demonstrate their propulsive force in the casting of these trajectories.

As any vigilant reader will know, 21.C fussed over its moniker as often as it changed editors: “Previews of a changing world”, “Scanning the future”, “The magazine of culture, technology and science”, “The world of ideas.” All of these missed the mark, for above all else the magazine was a preparatory guide, a concentration of reconnaissance dispatches from the future: 21.C: Mode d’emploi, a user’s manual for the world to come. On the occasion of 21.C’s passing, I spoke to publisher Ashley Crawford and editor Ray Edgar.

DT Tell me a bit about 21.C’s history.

AC & RE 21.C has had, to say the least, a tumultuous history. In a funny way 21.C has been a bit of a who’s who of Australian publishing. It was started in 1991 by the Commission for the Future, and it’s interesting to see how it captured so many imaginations. While it was Australian everyone wanted in: Barry Jones, David Dale, Robyn Williams, Paul Davies, Margaret Whitlam, Phillip Adams, the Quantum mob, lots of savvy media folk. After Gordon and Breach took it over and approached us in 1994 it went international and changed dramatically. Our mob was more R.U. Sirius, Kathy Acker, Bruce Sterling, Rudy Rucker and John Shirley; still big names, just in different circles. A different beastie altogether.

DT 21.C has been a focal publication for discussion of contemporary culture and technology. Why is it being discontinued?

AC & RE In effect it is being discontinued as a magazine but will live on as a series of books by regular 21.C contributors. However as a magazine in its most recent incarnation 21.C suffered from several problems. The company publishing the magazine is a successful publisher of highly specialized medical and scientific journals. 21.C was far from specialized in that respect and accordingly the company had great difficulty working out how to market a title which had broader appeal. Without marketing it was difficult to establish the nature of the magazine in the public’s eye. There was also the problem of advertising. As an editorial policy we avoided sucking up to the Bill Gateses of the world. The material was not about promoting product and when products were discussed such as Microsoft, Disneyland, Nike, software etc, it was usually with a critical tone as opposed to fawning. Most magazines rely upon press releases to inform them, we relied upon our writers and our instincts—probably a mistake.

DT In his Introduction to Transit Lounge [a recently published 21.C anthology, see review on page 25] William Gibson described 21.C as “determinedly eclectic.” What kind of audience were you attempting to reach?

AC & RE Again a problem. Given that the magazine’s brief was the future, well the future effects “everyone” and that was reflected by readers’ surveys. We had subscribers ranging from unemployed 18 year old hackers through to US Vice President Al Gore, scientists, graphic designers, architects, you name it. Given that it wasn’t being actively marketed towards any specific segment, well, Gibson got it right when he described it as eclectic.

DT 21.C provided an important space for Australian digital artists to get their work out into the international community, and looking through the catalogue of back issues, the promotion of new media arts was one of its most consistent features. How important was this to your editorial policy?

AC & RE Very important. One of the most amazing things about our work with digital artists and illustrators is that we could confidently state that Australia produced the best work in the world in this field. 21.C’s main sales ended up being in North America and we regularly received parcels from San Francisco and New York illustrators trying to get a gig in 21.C. However there was no comparison to the work being done here by Troy Innocent, Elena Popa, Murray McKeich, Ian Haig, James Widdowson and others. It was a wonderful challenge to illustrate the magazine. Given the futuristic topics we couldn’t exactly send a photographer to 2020 to take a snap. The illustrations had to reflect the content, but could rarely be literal. They were impressionistic images of a world yet to come.

DT It could also be argued that 21.C really got into discussions of multimedia art before anyone else. What’s your sense of the magazine’s contribution to multimedia criticism?

AC & RE Well naturally we would hope that it has a lasting impact. I strongly believe that the writings of McKenzie Wark, Mark Dery, Bruce Sterling and in a more quirky sense R.U. Sirius, Rudy Rucker and Margaret Wertheim stand up very strongly indeed. Really, not many other publications have delved into multimedia criticism as heavily as 21.C with the exception of MediaMatic, which definitely leads the field in terms of words, but which unfortunately doesn’t have the budget to illustrate the discussions as lavishly as we did.

DT In the final analysis, you always had a problem with categorisation, didn’t you? Do you think in the public imagination 21.C was over-identified as an internet/cyberculture publication?

AC & RE Yeah, people described it all sorts of ways. A socially aware Wired, an intelligent Mondo 2000. But it was by no means a Wired, and it was not really what you’d call an internet magazine, although as a subject area that was a regular element. But it was more what was being done creatively on the New, eg Mark Amerika’s Grammatron or Richard Metzger’s Disinformation, than it was about commercial or technological developments. 21.C was, essentially, a cultural studies magazine produced in an age of cyberbabble, trying to make sense of the creative furore in an undefined cultural era.

Darren Tofts is the author (with artist Murray McKeich) of Memory Trade. A Prehistory of Cyberculture forthcoming 1998, Craftsman House. He is also working on a collection of essays on art, culture and technology.

Some aspects of 21.C can still be found here http://www.21cmagazine.com Eds. 2013

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 24

© Darren Tofts; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

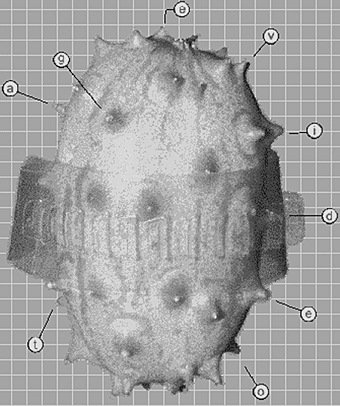

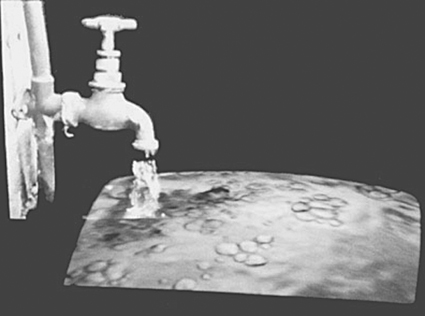

Tee Ken Ng, Untitled

Part of the wonder of encounters with artworks is the juxtaposition between your own efforts to comprehend a piece, if that is what you do, and the intepretation presented in the ‘artist’s statement’. The disjuncture that can at times emerge prompts some questions. To what extent is an artwork independent of its accompanying text? (Can or should it even be thought in such terms?) Does the extra-discursive nature of experimental artwork sabotage the potential it may have to correlate with the logic of written statements of intent, flimsy as they often are? These are some of the reactions I had to two exhibitions that use decommodified and new technologies to explore both the place and use of technology in culture and society.

Electronic media are used by three of the seven artists in fresh, an annual exhibition at PICA where select emerging artists dialogue with a curator—PICA exhibitions officer Katie Major this year—as they develop their artworks for public display.

Tee Ken Ng’s installation Onto Itself makes use of reflective smoked glass to form a pane of illusion between two television monitors on which usually incommensurate subject matter converges: a running tap bubbles water over one TV surface; a suspended glass mug contains a straw of TV static; a digitally produced inanimate object contracts and expands its way into life as it passes, somewhat paradoxically, through TV static in an evolution of descent. While these arrangements do have a momentary fascination that comes with their peculiar form of presentation, they are less successful I think at communicating the counter-discourse on or critique of televisual discourses suggested in the artist’s statement.

Similarly, Neale Ricketts’ statement promises interesting things for Click, a large video projection of mostly indistinct images: “By comparing the nature of the format (film) with the essence of the subject (waste), I am hoping to encourage an exploration into notions of waste and its by-products, which thus recycled, are able to once again, be meaningfully consumed by our society.” Unfortunately, such ambition, important as it is, does not translate across to the work itself. Ricketts is also interested in issues of public surveillance by video cameras, and signifies this to a small extent by placing at the base of the video projection two video monitors with connected cameras, one of which transmits the image of the audience onto a monitor as they enter the installation space, while the other just points to the second monitor.

Part of the problem of employing new technologies in artwork as vehicles to communicate a critique of the technologies’ attendant culture, is that the capacity for dazzle tends to overwhelm the subject of critique. The artwork becomes a display of what technologies can do, rather than an articulation of, say, decommodification and cultural practices of consumption.

Across the car park divide from PICA, in the modest space of Artshouse Gallery, is an exhibition of sculptural works by visiting Melbourne artist Michael Bullock. Resting on cardboard supports poking out of one the gallery walls, are 10 cardboard scale models of obsolete technologies: TVs, a vacuum cleaner, a toaster, speakers, a tape player, an iron, a record player. Above each object is a typewritten text, usually a humorous anecdote of the artist’s habit of collecting and accumulating various mechanical and technological devices manufactured mostly in the 70s, only to then store them in a closet or back shed as a particular item fails to perform beyond its use by date.

Like Ng and Ricketts, Bullock too is interested in the kinds of peculiar things we do with technology in its stages of decommodification. Quite different though is his strategy of expression, avoiding the risk of the technology of production overwhelming its product, the artwork itself. His cardboard models, which could well have been pre-assembly line prototypes, stand somewhat pathetically as items once desired for their sheen and ‘new frontier’ domestic status. In some cases, objects like the record player or toasted sandwich maker have undergone a process of recommodification as the item attains a kitsch or cult value status. Bullock’s text and sculptures are mutually constitutive of each other, with the text situating the junk technologies in a contemporaneity that is both out of the closet and away from the ignored display shelves of manufacturer’s showrooms, if such things exist.

fresh, an exhibition of installation, time based and electronic media works, curator, Katie Major, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts (PICA), March 26 – April 26. End of the Line, a project of sculptural works by Michael Bullock, Artshouse Gallery, Perth Cultural Centre, April 17 – 26

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 30

© Ned Rossiter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

After receiving relatively small amounts of support (nominally ‘program grants’) from the Australia Council in 1996 and 1997, the Paige Gordon Company failed to receive subsequent funding towards a new work Raising the Standard. Arts ACT, the company’s main funder did support the creation of the work. However…

JP What made you want to leave Canberra?

PG Although we didn’t receive Australia Council funding, we have been pretty well-funded by Arts ACT—the second best funded company here. However, dollars funding is one thing, support in terms of ongoing administration is another altogether. They fund you to a point and then expect you to survive. So no company in the ACT ever gets a chance to grow. In terms of a full-time dance company, $80,000 just doesn’t cut it. It’s crazy. And they have an expectation that you’ll do the work for free, and you’ll keep on doing it for free. And that’s ‘quote-unquote’ what they’ve said to me. There’s no valuing or comprehension of what a full time contemporary dance company means. It’s happened to a few companies, dance companies in particular—Meryl Tankard going, Vis a Vis going, and then Padma Menon going. So if my skills are going to be better rewarded somewhere else in the marketplace, then I’m going to seek out that opportunity. That’s exactly what I did.

JP Is it also more difficult now with the presence of The Choreographic Centre?

PG I guess as soon as that was set up and well-funded, it was going to be knock out competition. The Centre gives little bits of support to lots of artists and so, in terms of grants, they’re actually pleasing a lot of people. And I’ve spoken to the artists who have been there and they say it’s a great opportunity. But in terms of development of their craft, I don’t know how much it contributes. And the Centre doesn’t have to build audiences—they’ve got a capacity of 60 in their theatre, and they’ll get that anyway because people are interested in dance. It is a good place to have a choreographic centre because Canberra is a transient place, everyone comes and goes. But in terms of follow-up for the artists, I’m not sure it meets a need.

Canberra’s a great place but people would love to have a dance company they could call their own. There are lots of people who don’t want The Choreographic Centre. And there are lots of people that, yes, they like seeing performances there but they don’t feel a sense of ownership. And whilst I think it is really true that The Choreographic Centre is fantastic nationally—where else could it really be other than the national capital—it’s a shame that things can’t be considered equally in funding terms. I think there is enough room for the centre and for a company and I think the funding bodies should recognise that.

JP How did you carve out your own niche in the context of bigger companies visiting more frequently and presenting work on a larger scale?

PG We’ve visited all the high schools in Canberra to help them with their rock eisteddfod performances; we do corporate gigs (like the opening of the Canberra museum and gallery); and we did the opening of Playhouse. I see dance as being a really vital part of living—not just on stage. And a place like Canberra is fantastic for that. It’s also great that Meryl Tankard and Chunky Move and the Australian Ballet and Bangarra come and do that big stuff, which then enables me to do work on the fringe and outside the mainstream.

JP What does the new position with Buzz Dance Theatre in Perth hold for you?

PG Well my work is going to develop—while I’m on salary, which is wild! And the dancers will be on salary and the studio is going to be heated and we won’t have splinters in our feet and we’re going to have administrative support and a production person. And I’m going to have a chance to be in the studio every day. I’m walking in big shoes—Philippa Clarke has been there for 8 years so there is really quite a high standard. The company also does a lot of regional touring, and a lot of school work, which is important for developing the next generational audience. As well I want to bring to Buzz the national network of contacts that I have.

JP Have you been happy with what you’ve done here?

PG Well it’s always easier to assess your work in hindsight. I think that most of the pieces that I’ve done, I’ve been happy with. I like to put a work on and then 6 months later look at it again, that’s part of the choreographic learning process. It does take years and I’m quite happy to spend my life learning the craft. I want to be able to say when I’m 60, ‘Yeah, I think I got about five shows right.’ I really want to keep evolving.

JP Are you leaving with any negative feelings?

PG The reason why I sought out the job in Perth was related to just knowing that after 7 years of going ‘please, please, please’ I couldn’t do it anymore. I knew that while we were going to be up for triennial funding next year from Arts ACT, we were also told that it was going to be the same amount of money. What did they want, my blood? So while I’m not leaving with any really negative feelings, I think Arts ACT do need to realise that if they want to nurture a professional dance company—or theatre company, or opera company—they actually need to look at how they’re structuring the grant applications for those organisations.

With the Australia Council, they funded us for 2 years running, and then they changed their policy so it was project-related funding. So, Made to Move for instance, who are quite interested in touring my work, are not going to take us on just the possibility that we may get funding for next year. So they take on the companies that have guaranteed funding for next year. So it’s a bit of a bad situation that dance has got itself into. I don’t know how, but it has.

The Paige Gordon Company production Party Party Party has received the support of Playing Australia and Health Pact and will tour in August.

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 16

© Julia Postle; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

If the addition of music to this the third Australia Council Performing Arts Market was welcome but predictable, the presence of new media arts came as a very pleasant surprise. Of course, an expanding number of performing artists work with the new media but expectations are usually of sound and screen works unmediated by any presence other than the viewer/interactor. As New Media Arts Fund Manager Lisa Colley reminds us later in this article, the fund is about this and much more.

Linda Wallace, director of the machine hunger company which won the tender to present new media arts at the Performing Arts Market, told me in a telephone interview she had proposed the “production of a set of useful information tools for the market.” She described the market as “an event which I viewed as an initial gateway to the Australia Council’s ongoing, long-term strategy for marketing new media arts.” She was also mindful that the market audience might not necessarily know much about the new media arts area, so the tools needed to be simple and accessible. machine hunger produced a publication, a video and organised the exhibition which also featured a range of CD-ROM works.

“The publication was cost-effective at A5 size, 24 pages, enabling space for 20 artists, companies or projects, one per page. I was project manager and editor, and Susan Charlton joined machine hunger as deputy editor of the publication, which we titled Embodying the Information Age.”

How did Linda go about selecting the artists? “From a list of New Media Arts fundees I curated the final group. I saw it as both a curatorial and a marketing project, primarily for new media arts, and secondly for the Fund and the Australia Council. So I didn’t curate on the basis of how much money different artists had received from the Fund, instead, the artists selected were diverse in their approach to new media arts, and also had a professionalism which could be relied upon to ‘deliver the goods.’ There are performance groups, digital/installation artists and crossmedia projects like Metabody. I put emphasis on the potential of the internet as both a medium for art and also as an information medium for festivals—it’s critical for festivals to understand how the internet can extend their reach, and the reach of featured art projects, to a global audience. Some of the festival directors at the market seemed to understand this.”

What was your prime aim? “To get the publication into delegates’ hands and later onto their bookshelves. It was something I felt that overseas and local delegates would want to take home with them, as it is a stylishly presented, useful object covering a number of areas and artists, and with email contacts. I was keen to avoid the paperfarm approach of stacks of ugly brochures and junk, and also the busy pop ‘multimedia’ aesthetic. In terms of design our exhibition, or stand, was minimal, with the eyecatching, jewel-like publication, a jumbo monitor showing either a CD-ROM work or the videotape which featured a larger range of new media artworks.”

I emailed Lisa Colley at the Australia Council for her account of the fund’s venture and asked, “Why New Media Arts at a performing arts market?” Lisa wrote back, “New media arts are broader than sound and screen cultures. We need to keep in mind the purpose of the fund which is based on interdisciplinary, collaborative work that crosses art form boundaries. Many of the artists supported by New Media Arts see themselves as performing artists, so we wanted to ensure a showcase for their work within the Performing Arts Market. A number of the shows, including Burn Sonata, Hungry and Masterkey in the Adelaide Festival and the market had their genesis with the current fund’s precursor, Hybrid Arts. As well, we wanted to ensure that works difficult to show as part of the Showcase [a set of half hour performances of excerpts from larger works—ed.] because of technical requirements were given an opportunity as well.

“Also, we knew that international visitors to the market were interested in looking at work that was outside of the international festival performance circuit. This could provide a broader range of opportunities for artists here in terms of residencies, exhibitions and so on. Many festivals have programs that cross over into exhibition and installation work. This proved to be true and we had substantial interest from overseas presenters who want to commission work, pick up existing work and, in longer term relationships, develop exchange opportunities.”

I asked Lisa about the value of the booklet, Embodying the Information Age. “We wanted to produce something that had a life beyond the market. It is critical that we can inform people about the work that is supported by the fund. Of course it only reveals a small number of the artists in this area, but they are representative of a much bigger movement. We have also put excerpts from the booklet up on the web pages that we developed to coincide with the recent launch of the New Media Arts Fund and we hope to add to this over time. As more work supported by the fund is created we hope we can inform people about the outcomes. This is something we are constantly being asked for, and is a way of value-adding to the grants process. The spread of information can be expanded by hyperlinking to artists’ sites as well as organisations like RealTime and exhibition sites currently being developed. As with the booklet, we’re not acting as agents for these artists—they have their own email and web sites and can be contacted directly about their work.”

What kind of response was there to the presence of New Media Arts at the market? “There was a very positive response from international delegates who thought it was a natural and timely addition to the market. I have now established contact with a small group of presenters and producers and we are in email contact and hopefully we should see some results. The artists so far have experienced a very positive response to the booklet with many of them having been contacted about work both nationally and internationally. It has proven a very useful tool for their own marketing and promotion. We have now circulated it to all our Australian diplomatic posts and have plans for further circulation nationally and internationally. It represents part of a broader advocacy and marketing strategy for the work of new media artists which we hope to develop further. The fund now having a more secure position within the Council will allow us to develop this approach more comprehensively and with a long term view.”

I asked Susan Charlton about responses to the New Media Arts fund initiative. She emailed back that, “The fact that we were tangential to the market was an advantage in that we could really fulfil an advocacy role without the same commercial pressures that a lot of other companies would have been under to make deals. In this way it was a well conceived first step—for the Fund and for delegates just beginning to think about the area. At the same time, contacts didn’t just dissolve into the ether. Lisa Colley from the Fund was also there to assist possible connections between delegates and the artists they expressed interest in.

“Also the fact that the market was associated with the Adelaide Festival, rather than being linked to the National Theatre Festival in Canberra as it was in previous years, was in our favour. The diversity and multidisciplinary nature of the festival program enhanced dialogue about the possibilities of artists of various sorts using new technologies in their work. Delegates were not just locked into a theatre mindset.

“Many were already familiar with new media arts, but there were several who weren’t. Those new to the area seemed to be propelled by forces greater than themselves. They recognised that there was a demand for new media arts from their audiences and they had to get up to speed to be able to create programs. The New Media Arts stall allowed them to take the first steps of inquiry without feeling foolish. Most attention came in the first days, but once the showcase program began everyone was very committed and focussed on that. However many purposely revisited us in the closing days to make sure they had everything they needed.”

Invariably the benefits of the Performing Arts Market are long term. It’ll be interesting to see how the new media arts figure in the next market in 2000 as more artists and performers generate more possibilities from their engagements with technology. In a forthcoming report we’ll look at the work of the various agencies involved in the promotion of new media arts.

New Media Arts at the 3rd Performing Arts Market was a project of the Audience Development and Advocacy Division of the Australia Council in association with the New Media Arts Fund, February 1998.

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 12

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

“The virtual attaches itself to the body to assuage its fears. The virtual is constantly reiterating: here is something, where actually there is nothing. The virtual is an appendage to life, the interface with life. The virtual belongs to the establishment of reality, not to what the virtual is accused of—unreality, immateriality.”

William Forsythe, Frankfurt Ballet

In this work dancers Hellen Sky and Louise Taube perform a series of playful meditations on the body mediated by technology. As in their earlier work The Pool is Damned, though highly sophisticated and proficient in its use of technology, there’s still some sense in the company’s work of the poignancy of early experiments.

“What does the weight of my flesh and bones have on this conversation?” the recorded voice in Mediated persistently asks.

The work is installed in Gallery 101 in Collins Street, Melbourne, an hermetic white studio with a set of experiments in progress. Aluminium frames form mirrors, frames, screens, trays. The audience moves to each of the installations as the dancers animate them. They lie in the tray of sand at the rear of the room, 2 dancers of almost identical stature, spooning, shifting as in sleep. As the bodies move, the sand makes a space for the lacy projections of bodies on the screen nearby. As often throughout the performance, the audience focus is largely on the dancers until they gradually notice the projected images. They tap one another on the shoulders and point to screens. Gradually they take in the 2 at once, the mode mostly required of them in Mediated which seems less interested with the possibilities of delays and disjunctions, occasional dominations, than the experience of simultaneity.

The dancers move to a standing frame and dance in tandem against their own captured images from the sand. The image of the bodies is amorphous, then all edge. Its shape confined to a smaller frame, the shape of the choreography blurs. We look at the real dancers, glean the shape of their dancing and compare it with its vapour trail in the virtual. There’s less sense of the technology intersecting the dance or attempts at creating a choreography of the screen.

A large central screen. On blue squares the dancers perform a mirror dance at its most interesting when their separation moves them out of synch. Their live images vie with projections of another body. A series of spots on the screen trigger lighting and Garth Paine’s interactive sound environment.

Then something quite distinctive happens. At the other end of the room suspended horizontally less than a metre above the floor is a large tray full of water, another aluminium frame but with a glass bottom. A camera underneath the tray looks up through the water at the ceiling. High above is a screen. As Hellen Sky moves over the water, Louise Taube pushes the tray from side to side. Sky’s projected image above is sharper than we’ve seen up to now, then screen and body turn to water. A filter emphasising facial planes, the live body is transformed, becomes radiant, golden. The ceiling of air conditioning ducts becomes painterly. The audience gaze goes from the real body, through the water to the ceiling. Our fears are temporarily dispelled. Suddenly the screen is a liquid space, the body breaks the membrane momentarily fulfilling our desires for something more than mediation. Soon one dancer operates the camera to look at the other and there’s a sense of the two creating something in real time, at play with the technology. The performers’ action agreeably shapes the audience’s attention.

The final sequence occurs in a corridor broken up by small red laser lights. At the end of the space a monitor relays recorded images of a dancer’s body—like architectural drawings of hips and thighs and feet. The dancers moving through the lights trigger this sensual cycle of body images on CD-ROM.

Later we go backstage to see John McCormick’s own ‘installation’. Along one wall, a set of vintage Amiga computers and the odd Apple, cords, plugs and keyboards balanced precariously. He tells us that some of the technology is so old now you can’t get it fixed. He’s had to take to it with a soldering iron.

The scale of Company in Space’s investigation is as impressive as we’ve seen in interactive dance in Australia. In concentrating on the interplay between the technology and the dancers, Company in Space are well on the way to creating a work of significance. At this moment, the projected bodies are so different from the live ones that an act of dissociation occurs, the audience giving each a different kind of focus. The technology searches for its aesthetic and we look for the live and screen bodies to begin a more equal conversation with the audience, but the sense of an emerging hybrid fascinates.

Mediated, Company in Space, Gallery 101, Collins Street, Melbourne for Next Wave Festival, May 2, 9, 16, 23

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 14

© Keith Gallasch & Virginia Baxter; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Angie Pötsch

photo Graham Farr

Angie Pötsch

Dancehouse’s Mixed Metaphor season of multimedia movement works will launch the MAP (Movement and Performance) season of dance events across Melbourne throughout June and July. Presented annually by Dancehouse, Mixed Metaphor provides a crucial platform for experienced choreographers and artists creating works which aim to push conceptual and kinetic attitudes and blur the boundaries between dance, text, sound, image, design, physical theatre and technology. The first week of Mixed Metaphor 98 features: an internet link-up between San Francisco and Melbourne, where text and body converge through a digital dialogue in Heliograph, devised and performed by Sarah Neville with Matt Thomas, Becky Jenkin, Nic Mollison, Nik Gaffney; an exploration of suburban architecture and secrets, Blindness, choreographed and performed by Gretel Taylor with Telford Scully, Renee Whitehouse, James Welch; a surreal mapping of the myth of St Sebastian inspired by the writings of Yukio Mishima in Out of the Schoolroom Window by MIXED COMPANY directed by Tony Yap. In week two, Margaret Trail performs ‘Hi, it’s me’, an investigation of the body’s relationship with transmitted sound; Christos Linou performs his portrait of addiction and the AIDS virus, FIDDLE-DE-DIE; Philipa Rothfield, with Elizabeth Keen, creates a conversation between logic and the body in Logic, and Angie Potsch paints and dances with light in temporal. The Mixed Metaphor season also features a number of site-specific installations: a collection of red books, Red herring, by Charles Russell; photographs of urban architecture by James Welch; Kitesend, a ‘moving’ installation employing paper sculptures, by Hanna Hoyne and Lou Duckett. At an open forum entitled metaphorically speaking on Sunday July 5 at 2pm, issues and ideas arising from the works in the season will be discussed. RT

Mixed Metaphor, Dancehouse, June 25-27 at 8pm & June 28 at 5pm; July 2-4 at 8pm & July 5 at 5pm

RealTime issue #25 June-July 1998 pg. 15

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Sound Mapping, Hobart Wharves

photo Simon Cuthbert

Sound Mapping, Hobart Wharves

Sound Mapping is a participatory work of sound art made specifically for the Sullivan’s Cove district of Hobart in collaboration with the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Participants wheel four movement-sensitive, sound-producing suitcases around the district to realise a composition which spans space as well as time. The suitcases play “music” in response to the geographical location and movements of participants.

The prime mover behind the project is Hobart-based musician Ian Mott. Mott holds a BSc from the University of Queensland and a Graduate Diploma of Contemporary Music Technology from La Trobe University. His prime artistic activity is designing, developing, building and composing for public interactive sound sculptures—currently in collaboration with visual designer Marc Raszewski and engineer Jim Sosnin. Ian is also a specialist in real-time sound spatialisation and the real-time gestural control of music synthesis and interactive algorithmic environments.

“Sound Mapping”, as Mott explains, “creates an environment in which the public can make music as a collaborative exercise, with each other and with the artists. In a sense the music is only semi-composed; it requires that participants travel through urban space, moving creatively and cooperatively to produce a final musical exposition. Music produced through this interaction is designed to reflect the environment in which it is produced as well as the personal involvement of the participants”.

Sound Mapping uses a system of satellite and motion sensing equipment in combination with sound generating equipment and computer control. Its aim is to explore a sense of place, physicality and engagement to reaffirm the relationship between art and the everyday activities of life. For Mott, “Digital technology, for all its virtues as a precise tool for analysis, articulation of data, communication and control, is propelling society towards a detachment from physicality”.

Sound Mapping, Hobart Wharves

photo Simon Cuthbert

Sound Mapping, Hobart Wharves

For music, the introduction of the recording techniques and radio in the early 20th century broke the physical relationship between performer and listener entirely, so that musicians began to be denied direct interaction with their audience (and vice versa). Sound Mapping addresses this dilemma, for Mott believes that “while artists must engage with the contemporary state of society, they must also be aware of the aesthetic implications of pursuing digital technologies and should consider exploring avenues that connect individuals to the constructs and responsibilities of physical existence”.

The Sound Mapping communications system incorporates a single hub case and three standard cases. All the cases contain battery power, a public address system, an odometer and two piezoelectric gyroscopes. The standard cases contain a data radio transmitter for transmission to the hub and an audio radio device to receive a single distinct channel of music broadcast from the hub.

Prior to the project’s commencement, Mott anticipated that “the interaction between onlookers and participants will be intense due to the very public nature of the space. The interaction will be musical, visual, and verbal as well as social in confronting participants with taboos relating to exhibitionism. This situation is likely to deter many people from participating but nonetheless it is hoped the element of performance will contribute to the power of the experience for both participants and onlookers”. From my observation, these are precisely the reactions that the project did receive.

There is some precedent for Sound Mapping. Mott explains: “Participant exploratory works employing diffuse sound fields in architectural space have been explored by sound artists such as Michael Brewster (1994) and Christina Kubisch in her ‘sound architectures’ installations (1990). Recently composers such as Gerhard Eckel have embarked on projects employing virtual architecture as means to guide participants through compositions that are defined by the vocabulary of the virtual space (1996)”.

As a participant myself, I found three-quarters of an hour of wheeling a quite heavy suitcase rather draining. I think of myself as reasonably fit, but I reached the stage where just dragging the case was as much as I could do, despite Mott’s repeated urgings to swing and swerve the trolleys through space in more creative patterns, so as to generate more varied sounds. Not an activity for the frail.

I have to say, however, that I liked the concept of the work very much and was struck by the visual and aural impact of the piece on the several occasions when I encountered groups of engrossed participants making their way around the wharf area. Certainly, well executed public events such as this one enliven the sometimes staid atmosphere around Hobart. It is good to see art-making genuinely getting out into a wider and participating community. The lively nature of Hobart’s wharf area over summer—Tall Ships and all this year—made it a good venue for such a project.

Sound Mapping, A Sound Journey through Urban Space, by Ian Mott with Marc Raszewski and Jim Sosnin, in collaboration with The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, January-February 1998, Hobart

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 45

© Di Klaosen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

A sizeable fold gathered at the very smart (or ‘bourgy’, depending on your perspective) Ngapartji Multimedia Centre in East End Rundle Street for FOLDBACK, the day long forum exploring media, sound and screen cultures, organised for the festival by ANAT (the Australian Network for Art and Technology). Richard Grayson gave a user-friendly welcome invoking the the 10th anniversary of the other summer of love—“the famous event in south-east England, where techno ecstatics transformed the urban psyche of hyper-decay and escalating pan-capitalism into trance and psychedelic experiences” (ANAT newsletter)—stirring our barely repressed British memories of driving minis through Essex out of our gourds, on the lookout for parties we could never find. Paul Brown who says he actually found the party, stirred some of the same nostalgia in his account of the slow emergence of multiple media practice as 30 years on the fringe, citing rampant conservatism behind the form’s status in the artworld as part of a global salon des réfuse. There was some sense in this hankering that “legitimacy” meant legitimacy in the visual arts world which suggested perhaps a narrower engagement with the arts than expected. This was happily contradicted in subsequent sessions that demonstrated the vital relationships between new technologies and writing, sound and performance. A very writing-based day all round.

Cyberwriter Mark Amerika re-traced his steps from underground artworld, performing “acts of voluntary simplicity”, through his swerve into publication with the cult hit The Kafka Chronicles, which hurled him unwittingly into the public sphere and onto the digital overground. While he was busy collapsing the distance between author and reader, his online publication network, AltX (www.altx.com) was attracting the attention of international money marketeers. Like a lot of the international guests at the Adelaide Festival, Mark Amerika seems to be able to pat his head and rub his tummy at the same time. He may have achieved some fame and a little fortune as web publisher, but he’s still addressing the frictions between electronic art and writing. His writing-machine (Grammatron) still grapples with spirituality in the electronic age, asking questions like “Who are I this time?” (www.grammatron.com).

ANAT’s first executive officer, cyber-artist Francesca da Rimini, took some of her own advice (Quick! Question everything) rudely interrupting her own spoken text with others emanating from her cyber pseudonyms gash girl, doll yoko and gender-fuck-me-baby.

In *water always writes in *plural Linda Marie Walker and Teri Hoskin, from the Electronic Writing Research Ensemble, linked up live with Josephine Wilson (WA) and Linda Carroli (QLD) who have all been part of the first joint ANAT/EWRE virtual residency project, writing together online to create a work entitled A woman/stands on a street corner/waiting/for a stranger. Duplicating the act of writing for a live audience was an interesting if slow process, producing some nice accidents of speech: the odd poetry of phonetic translations, the Simple Text voices reproducing typos; suggestive intervals between writing and spoken text. You can read the piece on http://www.va.com.au/ensemble/water

Programming Linda Dement after lunch was a brave move. Still, it was soothing to hear a female voice in the dark still in love with the possibilities of technology for realising her expert if sometimes gruesome images. You would expect a sustained sequence of bloody bandages accompanying a diatribe on censorship to empty a room but here the pleasure of seeing the work of this former fine-art photographer projected on such a scale and in such vivid detail held too much fascination. Me, I spent a lot of time looking at the floor. Afterwards, diatribe met diatribe when a man in the crowd accused Linda Dement of male-bashing, citing “the situation in Bosnia” and then “all of history” as reason enough to censor, presumably, any statements along gender lines.

No wonder the cheery Komninos Zervos with his Underground Cyberpoetry received such a warm response after this error type-1. His CD-ROM was produced while Komninos was ANAT’s artist in residence at Artec (UK) last year. Using performance-poet delivery and adopting an assortment of streetwise London personae, Komninos playfully navigated his word animations. Screen became spin dryer, words tumbling as Komninos moved among us. The performance potential of multimedia works is really only beginning to be explored in Australia. Outside groups like skadada in Perth and Company in Space in Melbourne, we don’t see a lot of performance engagement with the new media. It’s an area that ANAT clearly see as important.

nervous_objects is an eclectic, accidental experiment in internet artistic collaboration. They met at ANAT’s 1997 Summer School in Hobart and have continued to collaborate online, in locations as remote as Perth, Woopen Creek and New York City exploring notions of realtime internet conferencing and manipulation of artistic pursuits in virtual and physical space. In their first project Lingua Elettrica (http://no.va.com.au) at Artpace and created for ISEA 97, they built an interactive website and publicly destroyed it. In a day otherwise free of technological accidents, nervous_objects encountered a few, making it sometimes difficult to decipher their precise intention. Their calm in the face of calamity produced a laid back form of subversion.

The stakes lifted when Stevie Wishart entered. Not an Adelaide Festival accordion in sight but improvising with medieval hurdy gurdy and live electronics she extracted an amazing array of sounds and tones. Real Audio was streamed from Sydney and mixed as it came through. As Stevie played, Jim Denley navigated the new CD-ROM track created with Kate Richards from Stevie’s new CD (Red Iris, Sinfonye, Glossa Nouvelle Vision GCD 920701).

In the energetic Q and A session, Mark Amerika brought up the need for new writing about multiple media, citing the likes of George Landau and Gregory Ulmer as critics who practice what they preach and engage with the work on its own terms. Chair of the New Media Arts Fund, John Rimmer, asked just how much technical difficulties (lags, delays, congestion) are intrinsic to the work and how they might develop given more bandwith. For nervous_objects, if it gets too fast, too polished it’s not interesting anyway. There was some discussion of Garry Bradbury’s score for Burn Sonata using pianola and digital technology. When someone in the audience thanked nervous_objects for sharing their process. Garry begged to differ, accusing them of utopian dreams of machines generating ideas. The nervous_objects said it was something that pushed them and they certainly didn’t expect the machines to generate ideas. Working with content issues was what they were doing. Afterwards all repaired to the Rhino Room for the launch of the excellent new CD by Zónar Recordings, Dis_locations, Incestuous Electronic Remixing, coordinated by Brendan Palmer. RT

FOLDBACK, ANAT, Adelaide Festival, Ngapartji Multimedia Centre, March 8.

An accompanying exhibition, possibly to tour, was exhibited at Ngapartji for the duration of the Adelaide Festival’s Artists Week. http://www.anat.org.au/foldback

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 27

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

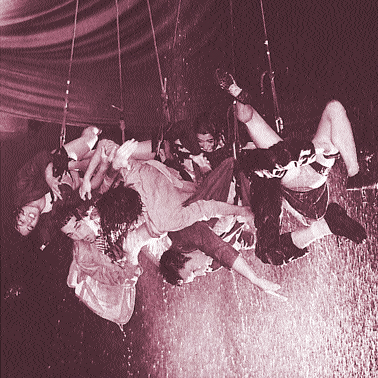

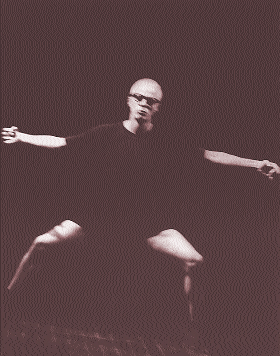

Meryl Tankard’s Australian Dance Theatre, Possessed

Regis Lansac

Meryl Tankard’s Australian Dance Theatre, Possessed

Prelude: The industry

While watching Performing Arts Market performances I was struck by the presence of performance stalwart Katia Molino, seeing her one day performing with Stalker, on another with NYID, both shows requiring considerable physical fitness and dexterity. It was a reminder that there is a broad body of work loosely defined as physical theatre within which various subsidiary forms exist and across which a number of performers participate. Thor Blomfield, one time performer with and now Marketing and Project Coordinator for Legs on the Wall, commented that given “there’s an increasing crossover between companies, for example Legs people working with Stalker”, just how valuable last year’s Body Contact Conference, convened by Rock’n’Roll Circus in Brisbane, was for an area of performance he describes as “encompassing a range of contemporary circus, physical theatre and street theatre groups.”

Blomfield said of participants Circus Oz, Rock’n’Roll Circus, Bizirkus, Club Swing and The Party Line, artists from Darwin, Legs on the Wall, Desoxy, Stalker, some overseas artists and others that “it was an interesting combination that had never come together before. The sense of community in physical theatre has been growing but this conference was the first time we’ve come together formally. It’s timely now to discuss where we all want to go and what we need to do in regard to training, funding and touring. The base for our work was in circus, in the foundation of Circus Oz 25 years ago and that was uniquely Australian though with the influence of Chinese training. Now physical theatre has moved into taking on more European influences and other Asian physical performance traditions.”

Asked why is it important for these groups to talk about the future, Blomfield explains that there are industrial issues to discuss, training proposals (a national circus school), the exchange of information (being informed about overseas work, the rare opportunities to see each other’s work), understanding how companies operate artistically (Desoxy, Stalker, Mike Finch—ex-Circus Monoxide, now director of Circus Oz—spoke about this on a Body Contact panel) and issues like the role of the director, which can be critical for ongoing ensembles working with guest directors. He indicated that there was some preliminary debate about what the proposed training school should do, whether it should provide conventional circus skills or also include, for example, courses in Butoh and various training regimes.

A committee was formed at Body Contact to hold a conference in October 1998 so that these issues could be pursued in more depth, perhaps even to consider whether or not to form an association of companies to promote the standing of physical theatre, which Blomfield describes as being sometimes treated by the broader theatre profession as “the little kid they really don’t know about”. Belvoir Street’s inclusion of Legs on the Wall’s Under the Influence in their 1998 subscription season could be the start of something. Other areas Blomfield would like to see explored include marketing (making the most of marked US interest), physical theatre’s relationship with dance (choreographer Kate Champion has directed Leg’s Under the Influence; one of the Legs’ team was advising Meryl Tankard’s ADT on the use of hand loops for their Adelaide Festival production Possessed) and speech in performance. Physical theatre has proved itself an elastic form, one rich in hybridity and political range as well as being eminently marketable: doubtless for the artists and companies in this area to confer regularly, to see each other’s work, to debate training and artistic issues, to think collectively on industrial and marketing issues, can only enrich their work.

Physical theatre dances

Legs on the Wall, Under the Influence

Adelaide Fringe Festival, February 25

I didn’t know what was cooking, the sausages sizzling at the entrance to the ‘performing area’ situated on the seventh floor of the carpark, or the audience beneath the tin roof in 40 degree heat plus lighting, say 45. Either way it wasn’t a good smell. And yet, Legs were cooking, giving a virtuosic physical performance despite being awash with sweat. They pretty much held their audience though it wasn’t clear how Legs were managing to hold each other. This is a company blessed with a kind of performance ease, physical feats are achieved without ‘drum rolls’ and the acting is laid back and lucid. To ease into this, a prelude of apparently casual exchanges and acrobatic events (and their ‘accidents’) unfolds as the audience enters asking has the show begun—well yes and no (except to say that this particular postmodern gag is a bit overripe and is somewhat scuttled when lights etc finally do mark a start. A pity.)

Physical theatre has always lent itself to the choreographic impulse (doubtless inherited from the lyricism of the circus trapeze artiste), and is certainly evident in Desoxy and The Party Line, but here, under the direction of choreographer Kate Champion, it goes further, not into dance per se, but into a dextrous patterning of moves and holds that provides a magical fluidity for the work, everything from small gestural motifs and work with domestic objects and clothing to large scale sweeps of movement and a coherent dance-theatre totality. It was fascinating to watch the thoroughness and the inventiveness of the movement and I found myself surprised at how much the performers must have had to absorb choreographically when already faced with considerable physical challenges. Legs are not to be underrated. As for the show as theatre, this early version was too discursive, key images (as the broad narrative works itself out) seemed to repeat themselves as long in duration as their original incarnations, one-off numbers looked more than suspiciously like unintegrated individual performer favorites, some scenes wandered too far from the dangerous intimacies central to the work, too many lines fell short of funny and into whimsy, personalities were just a little too abstracted, and the overall shape plateaued early, a not unfamiliar problem for physical theatre with its constant battle to escape the string of tricks. But for all of this it’s very good and by the time Under the Influence reaches its Sydney season hopefully everything that already works—the physical skills, the choreography, the ease of playing, the sensual energy and cheery fatalism—will be sustained by tighter scripting and shaping.

Dance does physical theatre

Possessed

Meryl Tankard Australian Dance Theatre

Ridley Theatre, Adelaide Festival, March 14

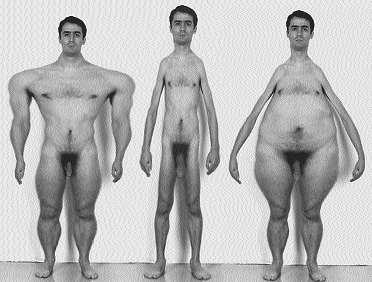

Possessed is the next stage of Meryl Tankard’s adventure with dance that leaves the ground, seen first in Furioso but also evident in another way in her choreography for the Australian Opera’s Orfeo. I have a vivid memory clip of her dancers as Furies flinging themselves relentlessly at a giant revolving wall. It looked dangerous. There is some harness work (first explored in Furioso) in Possessed’s central scenes, but the impressive new material that frames the show in the first and last scenes suspends the dancer by wrist, or by both wrist and ankle, using loops. While doubtless placing enormous strain on joints and muscles, there are advantages for fluidity and freedom of movement for the dancer in the air. Of course, it’s not a trapeze and they’re starting from the floor, so there’s not a lot they can do by themselves without help from the ground, the push that leads to swing as their earthed partner determines the direction of the swing and acts as catcher and cradler (and assistant). That said, once airborne, the dancer can amplify their swing and create delicious physical shapes and defiant arcs out over the audience. It looks dangerous as the arcs extend and the dancers swing fast and low over the fence around the big stage. It’s exhilarating because it looks so free, so unencumbered. And these dancers look so at home taking the grace they defeat gravity with on the floor into the air. The opening scene featured male pairs, generating a surprising intimacy, the aerial device allowing them ease at lifting the fellow male body, leaps into space being taken off the body of the ground dancer, returns from space greeted with great care. That aside, the women dancers provided some of the most spectacular and unnerving flights. If Possessed has any meaning, it tells of an obsession with flight and the defeat of gravity. Psychoanalyst Michael Balint called these possessed “philobats”, lovers of flight, and suggested that we all have some of that obsession in us, though we’re mostly happy to let others do it for us, at the circus for example. Not surprisingly then, the audience for Possessed clapped and cheered at every stage of these flights.

Another possessed body appears in the second scene—an obsessive sporting body, its centre of gravity low to the earth, absorbing everything in its almost militaristic path (shades of NYIDs’ monopolistic one-dimensional fit body at the Performing Arts Market), first possessing individuals in separate gender groups and then obliterating even that difference, taking with it every expression of pain and anxiety and the strange shapes that pitifully express them—a clawing fall to the floor or a wipe to the eye. A later comic scene has a group of men parading like women in a beauty contest—high heels and parodic stances (but around me the audience broke into shrill cheers exclaiming, “the Chippendales, the Chippendales!”). A line of women in red dresses challenge the men to do it right and all but one fail and exit, the victor taking his place centre line, locked in the same smile he began with, totally absorbed.

Much else in the evening seemed incidental, making it a show of bits and ultimately a bit of a show, despite the consistently powerful contribution of the Balanescu Quartet. The first, second and the final scenes of Possessed could be assembled into a powerful work instead of the sprawling entertainment it unashamedly is. Some in physical theatre might see Tankard as appropriating their aerial space, and there are times when the showbiz of it all seems to say so, but physical theatre is not all circuses these days and Legs on the Wall have a choreographer-director who’s worked with DV 8. Stalker have come down off their stilts and are working the air in other ways. It’s an intriguing physical moment.

Gravity Feed, The Gravity of the Situation

photo Heidrun Löhr

Gravity Feed, The Gravity of the Situation

Embracing the unbearable

Gravity Feed, The Gravity of the Situation

Bond Store tunnel, The Rocks, Sydney

March 19 – 22

Gravity is upon us, from above and from beneath. It is weighty, it sucks, it pulls, it compels and commands from all sides. We act because we must, bound to this archaic form the cube which contains nothing yet everything. This is the tabernacle of damned creatures, and in its lightness is the source of their constant anxiety. Program note

Part of me wants to read this show literally. I resist. This is performance. We all inch our way in past signs that intimate danger. We are in a high ceilinged tunnel not in a theatre. Men in tired suits, some unshaven, hair straggling or shaved creep and dart about, oblivious to us, gathering lit candles in paper bags, placing them on a high ledge above a tall ladder, or in a cluster on the ground further down the tunnel. Me, I think I’m witness to some tramp ritual, a subterranean fire-worship culture, such is their care for their charge, fire that disintegrates that which is heavy into flame and ash as light as air. A soundtrack rumbles the resonant tunnel into a hymn of unremitting threat and mystery. It doesn’t let go of us. One of the men tugs at a huge metal cube walled with what looks like triple-ply cardboard (light but remarkably tough) and lets it roll down the slope of the tunnel, barely impeding its speed with all of his bodyweight. This is the first of the journeys of the cube, a miraculous device, Prometheus’ boulder to be rolled endlessly up the slope, a self-generating Platonic ideal that grows new walls as soon as old ones fall away (great design and construction), a perfect material to ignite (it takes and then refuses, glowing like a Red Milky Way), a tabernacle for unwilling worshippers whom it sucks to its centre from time to time and then once and for all. I can read The Gravity of the Situation literally, not as a tramp fire cult, of course (but what about those swinging buckets of flame?); it’s what it says it is, its heavy heart upon its sleeve. But lightness is as feared as much as gravity in this inverted Manicheanism. In a delicate and suspenseful moment the men hold the cardboard walls they’ve liberated from the cube vertically above their heads and criss-cross the space fearfully, juggling the surface area of the walls against the air in the tunnel.

The Gravity of the Situation is something more than the beginnings of the great work we’ve all been expecting from Gravity Feed after The House of Skin. What it needs now, now that the scenario is there, the shape is there, the marvellous cube is there, is for all the attention possible to be lavished on the choreography of bodies and space, a distillation of the opening, the establishment of a surer relationship between performers and Rik Rue’s awesome sound composition, and even perhaps opening space in the soundtrack so we, the congregation, can hear the performer bodies groan against the weight of the light and the heavy. In the past, Gravity Feed works have evaporated. Isn’t it time to embrace the unbearable lightness of being?

–

RealTime issue #24 April-May 1998 pg. 33

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

This is a strange experience; not weird, not wild, but odd. The odd opportunity to see one video several times and to read it differently (or not) each time because its soundtrack changes, each video voiced in a new way. I say voice, because voice, sung and spoken, is pivotal in this performance. Onstage three female singers, sometimes four, synch into spare soundtracks, adding to instrumental and/or vocal lines, or going it on their impressive own. As a music concert it’s mostly great, and gets better as it goes.

Often we don’t ‘hear’ soundtracks (even when moved by them), unless they’re as obtuse as the Titanic’s or packed with favorite tunes, unless we’re soundtrack addicts. In Voice Jam & Videotape image and music are almost in equal partnership. “Almost” because it’s the films in this performance which are repeated, not the musical compositions. Each video enjoys the benefit of two or three accompaniments. Although this is a Contemporary Music Events’ gig, it’s still a matter of music servicing the videos. (CME has produced a show where you sit in a cinema and listen to music without film.) Kosky tries to keep the balance by placing his singers next to the screen. By the last screening, I know what I’m inclined to look at.