Avatar theory and a necessary hysteria

Darren Jorgensen: Darren Tofts, alephbet

Underlying the collected essays of Darren Tofts’ alephbet is the audacious, anti-historical idea that the internet can be thought about through films and works of literature that preceded its invention. To play out this provocation, Tofts chooses writers whose stories are game-like, such as Italo Calvino, Gilles Deleuze, Roland Barthes and above all Jorge Luis Borges.

Underlying the collected essays of Darren Tofts’ alephbet is the audacious, anti-historical idea that the internet can be thought about through films and works of literature that preceded its invention. To play out this provocation, Tofts chooses writers whose stories are game-like, such as Italo Calvino, Gilles Deleuze, Roland Barthes and above all Jorge Luis Borges.

Alephbet is presumably named after the Borges story “The Aleph,” about a point in space through which it is possible to see all other points. Borges is a character in his own story, and is introduced to the Aleph by a rival writer, Carlos Argentino, who is trying to emulate the effects of the Aleph in a long poem. Borges himself shies away from the Aleph, feeling more intimidated than inspired. He tries to distance himself from Argentino, whose aspirations he finds insufferable.

Of the two characters, Tofts resembles not Borges but Argentino, as the essays in alephbet are about the internet, that great portal of simultaneity in our own time. In so doing Tofts confronts the paradox of the Aleph, that aspires to contain everything in space including itself, and yet appears to lie outside everything too. To describe the internet is to describe an everything that is also a something, a thing that is also nothing, an immense multiplicity that seems to hold in its grasp the world itself.

So it is that Tofts resorts to a literary archaeology in which Borges stars prominently, because his writing describes textual mazes that stand in for the frantic contemporary experience of searching and linking, connecting and disconnecting. The analogy is a compelling one, not least because the historical Borges, as well as the character of Borges in “The Aleph,” stand perpetually outside the internet and its ecstasies, maintaining a sensible distance.

Tofts’ turn to Borges and other literature of the mid-20th century would seem a sensible move, in order to put some distance between the present and the past, to begin to cognitively map the virtual age. In literature lie cognitive precedents for both the disorientation of the labyrinth and its mastery, for navigating the infinite rather than being paralysed by it.

The stories of Borges come in alephbet to look like a roadmap for navigating the early 21st century, anticipating the hypertextual ecstasy of the internet user. In the indefinite narratives of Borges’ stories lie guides to the ways that conventional narratives can be circumvented by new links, new information.

The essays in alephbet use Borges as a bit player in Tofts’ much greater ambition, to create writing that is adequate to the everyday experience of the internet. They do not put a distance between ourselves and this most permeating of media, but create an hysterical present by which the possibilities promised by the internet might come into being.

For Tofts’ version of the internet is also bound to its most utopian moment, the late 1990s, as his theories revolve around terms like avatar, cyberculture, hypertext, media art and virtual worlds. In “Virtual curb crawling, lurkers and terrorists who just want to talk,” online sex is the key to understanding digital culture of this moment in our recent history, when the prophesies of cyberpunk seemed to be coming true. A wave of art projects took up the challenge of being adequate to the new virtuality. Internet Explorer, Bjork’s Post (1995), VNS Matrix and Stelarc are conjoined by Tofts’ ecstatic investigation of the way that bodies took on new meaning as they connected digitally.

“Virtual curb crawling” is symptomatic of a second paradox that haunts Tofts’ essays. This is the problem of doing a media history of the present while also describing this present, critiquing Internet Explorer while having it open on your desktop. The problem is unavoidable when it seems, as it does for Tofts, that the future has already arrived, that it came into being some time ago, as history became mired in the simultaneity of cyberspace.

The essay “Epigrams, Particle Theory and Hypertext” reports on the visual epigrams that punctuate the writing of Borges, Calvino, and Deleuze and Guattari. These little designs create miniature analogies for the circularity of their ideas, for the traps they lay for the reader. Calvino’s novel If on a winter’s night a traveller (1979) begins only to begin again, never completing a story but creating a succession of first chapters. Calvino’s novel is about the impossibility of writing, as the novel remains trapped by its own infinite possibility, its labyrinth of potential.

Cinema, too, furnishes Tofts with metaphors for the virtual revolution. Essays on the retro-futurism of Alphaville (1965) and the Deleuzian time-image in The Matrix (1999) work to unravel some of the paradoxes of an age steeped in technology. The hero of Alphaville photographs everything with a flash camera, momentarily blinding this imaginary future for posterity. The Matrix slows down time, as the action sequences of super-powered avatars are choreographed to suit human perception.

Borges is often cited as the forerunner of everything from magic realism to postcolonial literature, if not postmodernism itself, but for Tofts such multiplicities have already collapsed into the digital now. To read Tofts is to breathe as if we are drowning in binary code, and it is in this ecstatic, hyperbolic universe that Tofts creates arguments about writing.

Most compelling are his descriptions of the avatar that cannot theorise its own existence except through writing, through representation. In taking the place of the self, the avatar rewrites the possibility of thinking about thinking. It writes itself as a writer. And we are all avatars of ourselves insofar as we spend increasing amounts of time online.

Alephbet may be a tricky read for those unfamiliar with the proliferation of references that Darren Tofts strings along in quick succession, but the kind of hypertextual model of writing that he proposes comes to seem sensible in a digital era that has us all immersed in its own multiplicities, even if in spite of ourselves.

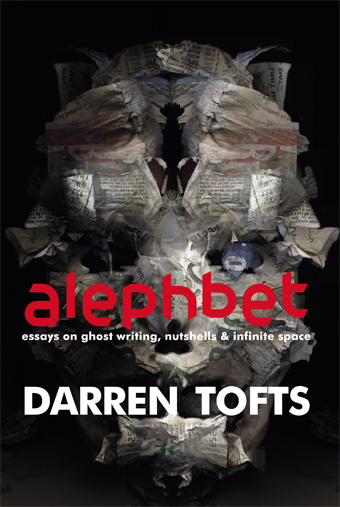

Darren Tofts, alephbet, essays on ghost writing, nutshells & infinite space, Litteraria Pragensia Books, Prague, 2013

RealTime issue #122 Aug-Sept 2014 pg. 29