Blimey!

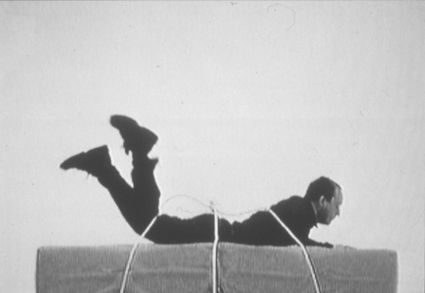

Steven Ball negotiates the rules of the game in British Bulldogs

John Wood and Paul Harrison, Device, UK, British Bulldogs

British Bulldogs screened as part of the Game Theory series of events presented by Experimenta Media Arts. The program title however is misleading, perhaps deliberately so.

On the whole Game Theory had an inconsistent relationship with the usual Pavlovian stimulus-response-reward scenario clichés that dog many forms of interactive gameplay. The Click Click, You’re Dead component addressed these scenarios fairly exhaustively via mainly commercially produced games; the Game Play exhibition featured playful game related local artists work and the speaking program discussed related topics.

Any behavioural analysis of the artist-viewer relationship would consider the shifting parameters of the ‘rules’ of ‘the game.’ Crucial to modernism, such considerations also can apply to a viewer’s approach to post-postmodernist exhibition: one does not have to decode so much as negotiate the packaging of curatorial conceit.

Through its title (a traditional British playground game) and vague allusions to “playing games” in the program notes, British Bulldogs strategically forged an oblique relationship to the theme, but the videos bore little relationship to games or gaming. By all but ignoring its obligatory thematic context, British Bulldogs became programming by stealth.

It was actually a solid program of recent British video works. Drawn from the catalogue of London Electronic Arts it mercifully avoided the self-conscious carryings on of the Young British Artists and their recent discovery of the camcorder, concentrating largely on a body of work tracing a number of interleaving, parallel concerns and experimental approaches.

In A.Z0.IC by St. John Walker, eerie morphed faces twisted into foetal shape-shifted animal forms accompanied by childlike rhymes (“…we had a dream last night, we had the same dream”). Blake’s Tyger, Tyger and floaty ambient music evokes some quasi-mystical synaesthetic cyberspace. George Saxon and Gina Czarnecki perform electronic prosthetics to create a mutant legless centaur with four torsos able to conceal and produce video cassettes, headphones and video monitors from within its person(s) in Homo-Cyte. Clio Barnard’s Headcase is a glorious mix and match; a self-referential, hammed up, mock-documentary, camp horror home movie about the benefits, thrills and dangers of all things connected with drilling into, removing and secreting heads from their bodies. While The Persistence of Memory by Anthony Atanasio is a far more conventionally stylish montage of associational image consciousness with advertising/music video aesthetics, images of extreme close-up faces, religious gesticulations, crucifix lamps in constant flash-back faux noir collision.

While these works explored the technological transformation of psycho-corporeality, their cross-genre quotation is a reminder that much of the experimental work produced in Britain is commissioned for broadcast funded by a combination of Arts Council and television. In spite of the predictable consignment of the works to the arts-end of programming this has meant that broadcast television has consistently been an important exhibition site and perhaps facilitated a certain degree of hybridisation. It also means that television isn’t necessarily perceived as some sort of low-cultural form ripe only for political interventionism or ironic appropriation.

Other works in this program reflected on the relationship between ‘human’ time and perception and a deeper, geological time span. John Smith’s Blight consists of a montage of largely static ‘still life’ images of a community of houses in the East End of London being demolished to make way for a new motorway. Smith selected fragments of former residents’ reminiscences about the houses and their lives there, “don’t really remember…don’t really remember much…” Set to music by Jocelyn Pook, it is elegantly edited to construct a sort of documentary song from a patchwork of voices, a contemporary folklore protest piece.

Withdrawal by George Barber presents a family walking across a field with a backdrop of hills, mountains and clouds, digitally manipulated so that ‘generations’ of family members disappear and landscape features recede at each repeat of the sequence. Fragments of dialogue about death and religion and trippy ethereal atmospherics suggest a cyberspace of deep time. This and Laws of Nature by Tony Hill evoke a less objective relationship with notions of time and ‘nature’, than might be suggested by the apparently romantic themes and subjects. Starting out looking dangerously like a new age tree hugging adventure Laws of Nature becomes a 25 minute visual poem. Through 360°, elegantly paced swooping camera movements across landscape features, rolling hills and English woodlands, with subtle time-lapse and double exposure, the film is an exploration of mechanically mediated perspectives without humanist ‘subjectivity’ in favour of extended geological space-time. In this sense it is, formally and conceptually, closely related to Michael Snow’s La Region Centrale in eschewing the human viewpoint (literally and perceptually) and the romantic gaze. Yet it has an aesthetic quality far less landscape-formalist covering a number of aesthetic techniques and hundreds of miles of England.

The transitions between millennia, while arbitrary, will it seems always have an impact on the political, cultural and social life of a country. In Britain this is happening in tandem with the devolution of Scotland and Wales which will lead perhaps to an examination of English ethnicity. The works in British Bulldogs suggest that this examination can be coupled with a reflective, but also adventurous, decentring of perspectives and perceptions. Blimey!

Game Theory, British Bulldogs, dLux media arts and experimenta, curated by Keely Macarow, Kaleide Cinema RMIT, Melbourne, July 16; Chauvel Cinemas, Sydney, Sept 29

RealTime issue #27 Oct-Nov 1998 pg. 23