Canny Robotics

Stephen Jones: Wade Marynowsky, Robot Opera

Robot Opera, Wade Marynowsky, Liveworks Festival, Performance Space

photo Heidrun Löhr

Robot Opera, Wade Marynowsky, Liveworks Festival, Performance Space

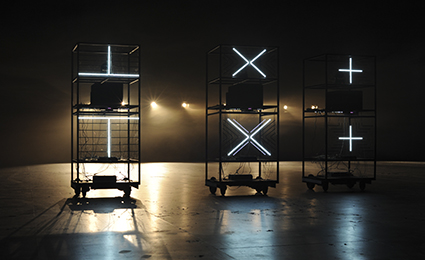

A row of eight standing rectangular frames appears at the end of the darkened auditorium, each emitting with strong LED light a pair of abstract geometric characters. The sound roars. The robots stand still as the characters flash and flicker; perhaps talking to each other in some alien robot language. The sound itself ripples as well. The robots wait as the sound forms into a martial beat at high volume, flickering characters matched by flickering sounds. They wait a few moments and then one robot rotates itself slightly.

At first they begin to move forward so slowly that you don’t notice. The activity of the characters decreases while on two of the frames a bright red light shines towards the rear. As the frames advance at a slow walking pace they follow individual trajectories and the audience moves forward to meet them.

These frames, about a metre square and two tall, are the robots. There are five shelves in each frame for the equipment which includes motorised driving wheels, an Arduino microcontroller and two motor driver circuit boards, a woofer speaker box under which is a Kinect depth sensor and a laptop facing the rear. On the top shelf is an infrared camera and a bright red lamp that spotlights the audience, with their images appearing on the laptop screens.

The sound becomes more subtle as the performance continues. The roar grows more self-modulated, with vocalisations in hard-to-interpret heavily phased single words, striking out into the space.

Marynowsky has abandoned the stately robots of his earlier work The Hosts and returned to a raw functional object that does not hide the hardware laid out on its shelves. They are disarming since they appear more like lab furniture than what we have come to expect. There is nothing approaching trunks, legs, graspers or heads. They show a medium level of autonomy. Each frame is equipped with sensors on the front and rear which stop the movement of the robot if it comes too close to a member of the audience or a wall. They move back and forth, pirouetting at various moments as the audience follows them across the floor or gets out of their way. The overall control of the choreography is via wi-fi from the master control laptop.

I call these robots lab racks because Marynowsky has dispensed with all notions of the humanoid robot or the 18th century automaton. Not controlled by mechanical levers and cogs, although the motorised wheels allow movement, they appear to possess some autonomy. But much of that is driven by the robot operators, Marynowsky and colleagues, tightly choreographing for their overall activity within the arena.

A group of delighted kids are the first to come into the arena and approach these well-behaved robots which seem to pirouette for approval, showing off their equipment. Of course the kids are of a generation for whom robots will seem a part of the everyday. Now the robots go their separate ways, mixing it with the audience: following, backing away, circling and generally wandering about as they take photographs of us which they show on their screens.

Robot Opera, Wade Marynowsky, Liveworks Festival, Performance Space

photo Heidrun Löhr

Robot Opera, Wade Marynowsky, Liveworks Festival, Performance Space

To what extent are these robots autonomous? Autonomy, at minimum, allows the robot to sense and navigate a fluidly changing environment, in this case a room full of people also navigating their ways around the robots. This sensing produces a feedback loop between the robot and its environment so that it can recognise the consequences of what it does. A non-autonomous robot will only produce outputs and will input nothing about effects.

In conversation with Edward Scheer (Liveworks, 31 Oct), Marynowsky detailed the modes of robot behaviour: “There’s a manual mode and there’s an autonomous mode. We call [the latter] ‘Avoid and Wander.’ It uses a laser scanner to avoid obstacles and people. There’s also another behaviour called ‘Follow’ where it moves after people depending on their x-y position within the space. So they’re the two main behaviours, they’re the two with safety mechanisms, as you might call them.”

In the finale the sound begins as a thick self-modulated chord and the robots realign themselves into allotted spaces marked with crosses on the floor. There they stay as the music plays out and the audience applauds, generously. Meanwhile the mob of kids sitting on the floor at the rear of one of the robots chatter excitedly. For all of us it’s a very satisfactory half hour or so.

The performance is not an opera. Yes, it is a gesamtkunstwerk, a total artwork involving the gathered artforms—a synthesis of sound and light and mobile robotic behaviour threaded in among a fluid and actively interested audience. The music is grand and imposing, there is no stage as such and no stage effects. Lighting is used to illuminate not to trick the eye. It changes in mood, following the robots’ progress and is echoed in the music. Without a star, a lead robot, the audience is completely central to the performance. Even though there is some oversight by the operators, the audience mingling with the robots provides a level of stimulus that affects each robot.

–

Performance Space, Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art, Robot Opera, artist Wade Marynowsky, music, sound design Julian Knowles, lighting Mirabelle Wouters, dramaturgy Lee Wilson, electrical design Ben Nash, programmers Imran Khan, Adam Hinshaw; Carriageworks, Sydney, 28 Oct-1 Nov

RealTime issue #130 Dec-Jan 2015 pg. 20