character issues

john bailey: meow meow, tony reck, rawcus & restless, melbourne

THE NOTION OF ‘CHARACTER’ IS LIKE A PROPERTY TITLE HANDED DOWN OVER HUNDREDS OF GENERATIONS, THE ORIGINAL DEED NOW LOST AND ITS BOUNDARIES, DIMENSIONS, OWNERSHIP RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF CARE TANGLED AND UNCLEAR. EVERY PERFORMANCE MAKER MUST FACE THIS MONUMENTAL INHERITANCE AT SOME POINT, AND ASK “HOW THE HELL AM I SUPPOSED TO SORT THIS MESS OUT?”

Postmodern performance often negotiates this tricky terrain in intriguing ways. Three recent Melbourne premieres exemplify the range of responses—and their attendant problems—that can be found in the wider artistic shifts of the past few decades. In one, irony and excess are used to push character over the brink of significance; in another, the concept of the consistent, ‘closed’ character is replaced by the character as a process of becoming; and in the third, the distinction between character, performer and audience becomes a pivotal dynamic.

The character as ‘type’ has a long history, from Greek comedy through commedia dell’arte to French satire to modernist drama. The individual may represent a social, psychological or cultural type—but it is this notion of character as representation, as an instance of an essential class, that is called into question in Meow Meow’s Vamp. In her first full-length work the already legendary cabaret artiste has sought to problematise the character of the titular vamp, the femme fatale, the lethal seductress, the desirable, threatening woman. This questioning, however, is accomplished not through an explicit distance but through a perilous closeness—Meow Meow becomes the vamp so perfectly, in all of her historical forms, that the figure is drained of substance, rendered a hollow goddess.

Meow Meow, Vamp

photo Jeff Busby

Meow Meow, Vamp

vamp

As a performer, Meow Meow is undoubtedly a star, with an astonishing vocal range and a powerful command over her audience. But Vamp is all masquerade—Meow Meow tries on characters like costumes, from Salome to Louise Brooks’ Lulu, borrowing songs along the way, snippets of text stolen from all over, the gestures of generations of chanteuses. This magpie approach is, itself, a pilfered costume, and the form of Vamp as well as its content is recognisable from both drag acts and the most hallowed of pomo pastiche. Meow Meow pushes it to the limit, though, and the density of allusion here gradually begins to suggest that Meow Meow herself is nothing more than her disguises—remove the mask and there would be no face underneath. This is reinforced by the mannequins and doll parts which appear throughout the performance, and her final number—a melancholy, quiet version of Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees”—brings it all home. Meow Meow is the copy that destroys the original.

the antechamber

The characters of Tony Reck’s The Antechamber are less immediately recognisable. They inhabit a kind of uncannily rendered Aussie noir netherworld with a distinctly David Lynch ambience, in which interior psychology and exterior reality are hopelessly indistinguishable. There’s a narrative of sorts—a flower-shop assistant and part-time drug dealer is visited by an old (yet strangely young) flame; the domineering shop proprietor seems to control him while also being under his control; the ex’s sinister new beau later brings the threat of violence into an already charged atmosphere. At no point can we trust any of these characters—not simply in the sense of ascertaining motive, but of even expecting a temporal consistency. They occasionally slip into types, but only just. Most of the time they are foggy, amorphous identities whose only definition is found in their interactions with each other and given the constantly shifting relationships, this too becomes untenable.

The performers here don’t seem to have fully realised the ambition of this open-ended work, either over- or underplaying things throughout. This is, of course, a difficult assertion to make, since the notion of getting it ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ is undermined by the very piece itself. In fact, to get it right—in a conventional, realist way—would perhaps render it obsolete. But as it stands, this difficult, somewhat dissatisfying production is as much in the process of becoming as its subjects.

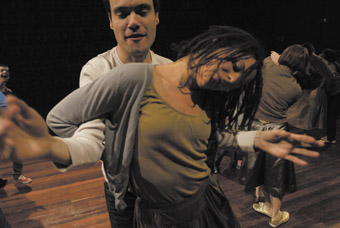

Clem Baad, Jay Kimber, The Heart of Another is a Dark Forest, Rawcus Theatre and Restless Dance Theatre

photo Paul Dunn

Clem Baad, Jay Kimber, The Heart of Another is a Dark Forest, Rawcus Theatre and Restless Dance Theatre

the heart of another is a dark forest

The Heart of Another is a Dark Forest explicitly takes on the issue of whether we can truly know another—at every level, it raises fascinating and provocative questions regarding performance, character and spectatorship. It’s the first collaboration between Melbourne’s Rawcus Theatre and Adelaide’s Restless Dance Theatre, both companies working with performers with and without disabilities.

As the title suggests, this is a work that tackles otherness—familiarity and difference, the space of encounter, the revelation and secrecy. It’s an abstracted, physically oriented piece with no discernible narrative arc, though there are frequent shifts of pacing and mood.

I’ve not experienced works by Restless before, but Rawcus’ previous productions have always struck me immensely with an intense, almost unique experience of presence. ‘Acting’ and ‘character’ depend on a kind of absence, a sense of an identity which is not the performer’s—hence the getting-it-right-or-wrong argument. Restless and Rawcus performers occupy a different space. Confronted by the physical liveness of a performer with disability, one is made more aware of the presence of the moving, sometimes speaking person rather than the more transcendent elsewhere of a character. There may be a sense of voyeurism at work, but this is something both companies play with, and nowhere more so than in this new collaboration.

The Heart of Another is a Dark Forest is a largely solemn, moody piece, as opposed to the lush playfulness of Rawcus’ last two works. Where Hunger (2007, see RT82, p8) and Not Dead Yet (2005) were revelatory in the way they allowed access into the interior worlds and experiences of their performers, this new work more consciously teases its audience by withholding information. What we choose not to reveal to others is as important as what we do: thus, we here find secret thoughts spoken anonymously, dancers turning their backs to the audience, text spoken in ways that are difficult to understand. This is a challenging, but thought provoking process: while I found the spontaneity and exuberance of Hunger, for instance, to be far more enjoyable, this work is an important reminder of the right of the performer—disabled or otherwise—to be something more than an exhibit for our curiosity.

There are some beautifully accomplished dance sequences: one especially in which partners provide arms for each other in a scene of massed duets that produces a wonderful sense of bodily communication. The power dynamics shift between each dancer and these shifts become the sequence’s expression. In another scene, a whisper passed down through a line of performers creates a real sense of hilarity as they react with genuine surprise to the phrase they hear. Whether, of course, this is just acting, is precisely the point. One walks away from this work wondering if we can ever know another’s truth, or if our ‘real’ self is in fact produced through the searching.

Malthouse, Vamp, by Meow Meow and Iain Grandage, performer Meow Meow with the Orchestra of Wild Dogs, director Michael Kantor, musical director Iain Grandage, designer Anna Tregloan, lighting design Paul Jackson, dramaturgy Maryanne Lynch, choreography Shaun Parker, CUB Malthouse Theatre, Sept 6-20; The Antechamber, writer, director Tony Reck, performers Phil Motherwell, Nada Cordasic, Wilfred Last, Jane Lundmark, sound Hugo Race, lighting Andre Conate, La Mama Theatre, Sept 17-Oct 5; Melbourne Fringe Festival: Rawcus Theatre and Restless Dance Theatre, The Heart of Another is a Dark Forest, directors Kate Sulan, Ingrid Voorendt, design Emily Barrie, costume Esther Hayes, lighting Richard Vabre, composition/sound design Zoe Barry, Jethro Woodward, performers Steven Ajzenberg, Clement Baade, Ray Drew, Rachel Edward, Nilgun Guven, Valerie Hawkes, Paul Mately, Mike McEvoy, Kerryn Poke, Louise Riisik, John Tonso, James Bull, Jianna Georgiou, Lorcan Hopper, Alice Kearvall, Jay Kimber, Kyra Kimpton, Dana Nance, Andrew Pandos, Anastasia Retallack, Stuart Scott, Lachlan Tetlow-Stuart, Bonnie Williams, Dancehouse, Melbourne, September 24-27

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 15