china sightings

gail priest: mu:screen, uts gallery

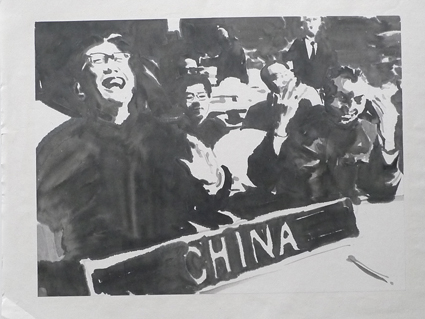

Looking, Looking, Looking for…, Kan Xuan (2001)

courtesy of the artist

Looking, Looking, Looking for…, Kan Xuan (2001)

GREETING US AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE GALLERY ARE TWO TRADITIONAL CHINESE LIONS. RATHER THAN BEING CARVED OF STONE, HOWEVER, THESE CREATURES ARE TRAPPED INSIDE SCREENS, THE LION ON EACH SIDE SPLIT BETWEEN TWO STACKED MONITORS. FAR FROM UNHAPPY ABOUT THEIR FATE, THESE LIONS ARE PLAYFUL, WINKING AT US, LIFTING PAWS AND SENDING OUT THE OCCASIONALLY PROVOCATIVE ROAR. THE WORK, ALWAYS WELCOME (2003) BY WANG GONGXIN, ONE OF CHINA’S LEADING VIDEO ARTISTS, OFFERS AN INVITING INTRODUCTION TO MU:SCREEN, AN EXHIBITION OF CHINESE VIDEO ART CURATED BY MARIE TERRIEUX AT THE UTS GALLERY.

The Dinner Table, 2006, Wang Gongxin

courtesy the artist, collection of the Neilson Family, White Rabbit Collection, Sydney

The Dinner Table, 2006, Wang Gongxin

Wang Gongxin contributes another sculptural video work, The Dinner Table (2006). An oversized tabletop on a precarious 60-degree angle acts as the screen for the projection of a fully set banquet table. Gradually we begin to notice that the sauce from some of the plates is seeping across the table, but defying gravity, oozing upward. Before long, food and cutlery are all impossibly sliding up and over the edge, accompanied by soft crashes and clangs, until all that remain are the stained tablecloth and a few napkins, which are also whipped off, surprisingly from the lower side of the table. Wang’s challenge to viewers’ spatial perception is a potent metaphor for the provocations that art can offer to established ways of seeing—particularly resonant as he is one of the first artists in China to push beyond traditional mediums to explore video.

Zhang Peili is in fact recognised as the first Chinese video artist. The piece included here, Water—Standard Version from the Dictionary Ci Hai (1992), features a news presenter reading the full nine-minute definition of the word for water from a dictionary. As there is no translation offered, the experience for an English speaker is purely conceptual, but the correlation with works by Western artists such as Bruce Nauman is clear. As Peili is such an important figure, it would have been interesting to experience at least one other work of his (as we do with Wang) to get a clearer sense of his practice and of the beginnings of video art in China.

There appears to be a clear lineage between Zhang and Wang’s work—in the manipulation of temporal qualities and the concentration on live action—expressed in the work of two of the younger artists represented. In Kan Xuan’s Looking, Looking, Looking For…(2001), presented on a small screen, a tiny spider skitters over naked male and female bodies, exploring every crevice and orifice. Both playful and disturbing, the work has the ease and directness of approach that characterises a generation born into a media and technologically driven age. Similarly, Ma Qiusha’s A Beautiful Film (2007) suggests an artist immersed in a critical exploration of screen culture as well as contemporary representations of sexuality. She uses close-ups of pornographic images to create a hazy, romanticised vision of beauty, accompanied by endlessly scrolling movie credits.

Liu Lan, 2003, Yang Fudong

courtesy of Shanghart gallery

Liu Lan, 2003, Yang Fudong

Yang Fudong, has recently been introduced to Australian audiences with his disturbing work East of Que Village (2007), presented as part of the recent Biennale of Sydney (RT97, p 46). A less harrowing experience, his work in this exhibition entitled Liu Lan (2003) is stunningly shot on 35mm black and white film (transferred to video) and focuses on a beautiful young fisherwoman on an eerily isolated lake where she is joined by a handsome man from the city wearing a white suit. It is a quiet, romantic vision of an impossible meeting occasionally undercut by the extraordinarily weathered face of an old woman, hinting at these as her memories or dreams. Under the veneer of idyllic beauty is a subtle sense of irony and social criticism that gives the work its intensity.

Flowers of Chaos, 2009, Wu Junyong; exhibited as part of Mu: Screen, UTS Gallery

courtesy of the artist

Flowers of Chaos, 2009, Wu Junyong; exhibited as part of Mu: Screen, UTS Gallery

Interestingly, three of the artists utilise drawing and animation. Most intriguing is Flowers of Chaos (2009) by Wu Junyong who, with his simple, almost naive line drawings, creates his own symbolic language to explore power, manipulation, repression and freedom in a strangely joyous way. Sun Xun’s People’s Republic of Zoo (2009) also explores these themes, with animal/human chimeras acting out symbolic power plays. Sun’s animation is a complex collage of styles reminiscent of William Kentridge—drawings, cutouts and actual video footage of shadow play—that bring to mind a dark, often opaque dreamscape.

The Ink History, 2010, Chen Shaoxiong

courtesy the artist

The Ink History, 2010, Chen Shaoxiong

With four works presented, it is hard not to see Chen Shaoxiong’s Ink series as the centrepiece of Mu:Screen. Created from hundreds of ink drawings, these simple animations often involve just flipping through different scenes, or at most a close-up or pan within an image. It’s the accumulation of detail that makes these works so powerful. Across the four screens, we move from everyday life in The Ink City (2005) to the personal in The Ink Diary (2006), to a micro view in The Ink Things (2007), ending with the macro in The Ink History (2010), an epic exploration of Chinese history. Chen’s work is particularly poignant, not only in its subject matter—the methodology itself illustrates the tensions between old and new media.

The UTS Gallery was well transformed to house the substantial number of video works in this exhibition, although the issue of soundbleed presented a problem. While some works were well served by headphones, there were still four soundtracks mingling in the reverberant, tiled space. The effect was exacerbated in the use of video projectors as audio source for two works rather than placing speakers in close proximity to the actual projection. This meant that sound and image became quite dislocated and confusing, particularly in the case of Sun Xun’s work.

Marie Terrieux is a freelance art consultant, with her own company, Shuang Culture, advising collectors and institutions and working with established and emerging artists from China and the region. Her thorough knowledge of the Chinese art scene is evident in this exhibition, which includes illuminating contextual information on the website. Terrieux’s choice to present artists across three generations provided a fascinating introduction to an area of art-making only just beginning to make the same impression as other Chinese art practices on the international stage.

Mu:Screen, three generations of video art, curator Marie Terrieux, artists Wang Gongxin, Zhang Peili, Chen Shaoxiong, Yang Fudong, Ma Qiusha, Wu Junyong, Sun Xun, Kan Xuan; UTS Gallery, Sydney; June 1-July 9; www.utsgallery.uts.edu.au; www.muscreen.com

Wang Gongxin’s The Dinner Table (2006) was lent to Mu:Screen by the White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney which houses the largest private collection of contemporary Chinese Art outside China. www.whiterabbitcollection.org

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 pg. 56