Culture’s haunted houses

Ben Brooker: 8th OzAsia Festival 2014

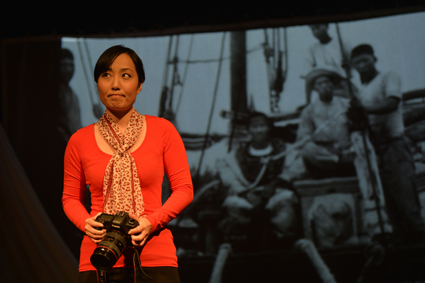

Ibsen In One Take

courtesy Ibsen International and OzAsia Festival

Ibsen In One Take

The focus of the 8th OzAsia Festival is on China’s Shandong Province, famed birthplace of Confucius and home to around 100 million people. A meeting place of ancient and modern trade routes and the location of culturally significant sites for Taoists, Buddhists and Confucians, Shandong’s historical legacy and agriculture- and natural resource-derived affluence are obliquely reflected in this year’s marquee productions Red Sorghum and Dream of the Ghost Story, by the Shandong-based companies Qingdao Song and Dance Theatre and Shandong Acrobatic Troupe, respectively.

Both are conservative, visually lavish works, seemingly model companions for the chatter about soft diplomacy and measurable cross-cultural benefit that inevitably orbits the festival. To the contrary, Mayu Kanamori’s ascetic docudrama Yasukichi Murakami—Through a Distant Lens strove for verisimilitude in its unsentimental summoning of early 20th century Japanese-Australian ghosts, and Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental’s flawed but enterprising glance at Ibsen’s oeuvre, Ibsen in One Take, provided food for thought.

Red Sorghum

Adapted from the 1987 Chinese language novel of the same name, the balletic Red Sorghum is a vast undertaking—around 50 dancers under the direction of Ge Wang and Rui Xu propel Mo Yan’s complex, generation-spanning family saga towards its bloody climax set during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). There are unpleasantly nationalistic overtones by the time this point is reached, Japanese ‘devils’ bayoneting their way across the stage without the leavening effect of the novel’s viewpoints from both sides of the conflict. But there is no doubting the vitality and precision of the preceding two hours. Especially impressive in this regard are the lusty, though strictly gender-segregated, distillery and harvest set pieces that take in the novel’s central metaphor—the versatile sorghum grass—and the masterfully sinuous love duets between lead dancers Meng Ning and Fubo Sun. Yuan Cheng’s recorded score is more of a mixed bag, most successful when least bombastic (I wasn’t surprised to learn it had been taken to Hollywood for mixing and production). A suona horn, a Chinese folk instrument with a distinctive high pitch, is a lovely addition to the otherwise predominately Western musical palette that, like the production more generally, ends up a somewhat over-rich concoction.

Dream of the Ghost Story

Shandong Acrobatic Troupe’s Dream of the Ghost Story is similarly predicated on spectacle but is also driven by it rather than by narrative—its use of a Qing Dynasty fable about demonic intervention in a love affair between a fox fairy (Zhang Xu) and a human scholar (Guo Qinglong) is nominal, a lightweight scaffold for the 55-year-old company’s well-honed legerdemain. Liu Kedong’s set design consists of a series of telescoping, parchment-like archways that hint at Dream of the Ghost Story’s folkloric origins but leave most of the vast Festival Centre stage open for the ensuing, virtually unstopping acrobatic displays: hoop and aerial work, plate spinning, juggling with hands and feet, Chinese yo-yoing, gymnastics, contortion and balancing. It’s heady stuff—there are no safety nets, and Guo Sida and Du Weis’ full-bodied, rock-accented soundtrack ups the show’s winningly deceptive uninhibitedness, most memorably during the second half’s descent into the spirit world when massed, incandescent skeletons judder, twitch and stomp à la Michael Jackson’s Thriller. A shamelessly entertaining fusion of ancient Chinese variety art and contemporary Western excess.

Arisa Yura, Yasukichi Murakami—Through a Distant Lens

Elise Derwin, courtesy Darwin Festival

Arisa Yura, Yasukichi Murakami—Through a Distant Lens

Yasukichi Murakami—Through a Distant Lens

The supernatural is also present in Yasukichi Murakami—Through a Distant Lens, a lean documentary performance work that quietly seeks to rehabilitate the memory of Japanese-Australian businessman and photographer Yasukichi Murakami who died in a Victorian internment camp in 1944. Murakami (Kuni Hashimoto) appears as a ghost to Mayu (Arisa Yura), playwright Mayu Kanamori’s analogue within the play. Their relationship begins with him softly rebuking her for taking photographs without, as Kanamori phrases it in her program notes, “taking notice, making an effort to hold space in reverence, trusting and responding in humility.”

The chronological rift between Murakami and Mayu only becomes clear when, by way of demonstration, Murakami sets up his box camera and photographs unseen members of his young family in Broome. Beautiful, high-resolution projections of Murakami’s actual photographs of fellow Japanese immigrants and pearling crews appear throughout the production but the play makes it plain that a shadow remains over his career—many images it is thought he is responsible for, some of which today reside in the National Archives and grace the covers of notable works of history, remain uncredited to him.

Director Malcolm Blaylock and visual designer Mic Gruchy imbue what is in essence a love letter to an unjustly overlooked life with the same reverence for space and attentiveness to detail Murakami demands of Mayu’s photographs. To say that Blaylock employs naturalistic performance, film, projection and a live score (composed and performed by Terumi Narushima, and which employs both traditional Japanese and esoteric instruments) makes the work sound cluttered but it is, rather, a dramaturgically crystalline—and ultimately moving—meditation on place, photography and the politics of recognition. (See also page 6.)

Ibsen in One Take

Henrik Ibsen’s problem plays have long exerted a significant influence on the course of modern theatre in China. Indeed, it took a conference on the playwright’s work in the 1920s for a Chinese word to be coined to distinguish spoken word drama from that which was, traditionally, sung. Ibsen in One Take, written by Oda Fiskum and directed by Wang Chong, feels like both an expression of and a reaction against the country’s longstanding fascination with A Doll’s House, The Master Builder and Hedda Gabler. There are close echoes of and occasionally exactly duplicated dialogue from each of these plays. The lugubrious plot centres on four iterations of the same man, called simply Him: as a child (Yang Boxiong), a young man, an adult (both Li Jialong) and an old man (Tan Zongyuan) who, nearing the end of his life, is confined to a hospital bed and reduced to pondering his past to assuage the boredom. Brief, intimate scenes flavoured with Ibsen’s familiar high-tension domesticity are arrived at through flashbacks.

The scenes are filmed by an onstage two-man camera crew whose vision appears on a large screen overhanging the space (the screen also displays English translations of the Chinese language dialogue). There are big problems, not the least of which is the conceit of filming the live actors ‘in a single take.’ Without a clear rationale, the footage feels extraneous; I felt no compulsion to watch the screen except for the surtitles. It is strange, too, that opportunities for enriching the production through the filming are often either mishandled or missed altogether. For example, a potentially delightful moment when a spray bottle is used to simulate rain falling on two actors is squandered because the water doesn’t show up on the screen. The camera usually lingers in close proximity to the actors’ faces, its gaze failing to either explicate or surprise, and the elusiveness of Fiskum’s script—a dour, slightly rudderless construction which strays too far from Ibsen’s psychological insights to prove affecting—remains largely unalleviated by its presence.

8th OzAsia Festival 2014: Qingdao Song and Dance Theatre, Red Sorghum, Festival Theatre, 3 Sept; Shandong Acrobatic Troupe, Dream of the Ghost Story, Festival Theatre, 5-6 Sept; Yasukichi Murakami—Through a Distant Lens, performers Arisa Yura, Kuni Hashimoto, Yumi Umiumare, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, 9-10 Sept; Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental, Ibsen in One Take, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, 16-17 Sept

RealTime issue #123 Oct-Nov 2014 pg. 5