Dance cinema, cinematic dance

Karen Pearlman surveys the 2006 ReelDance finalists

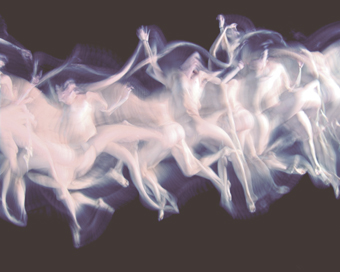

Gina Czarnecki & Garry Stewart’s Nascent

ReelDance 2006 is the 4th bi-annual dance on screen festival curated by Erin Brannigan since 2000. As a not dispassionate observer, writer and participant I have seen the styles, approaches and personnel of the finalists (10 Australian or New Zealand made short films selected for screening in competition) change intriguingly over this time, sometimes reflecting trends and sometimes setting them.

After the first ReelDance I wrote that the finalists were “not the usual suspects” (RT38, p15). That year they were drawn from art schools, were experimental filmmakers, or mostly unknown choreographer-directors. There was a thrilling sense that, with the advent of a dance on screen festival, the previously unseen would be visible and that artists might lead the way in developing an art form. They could change rules about dance that had been, up to then, drawn strictly along the lines of association with known artists and funding bodies.

In the next 2 festivals the finalists mostly seemed to have lost their edgy freshness, and it was not replaced with energetic or informed accomplishment in the cinematic arts. There were, of course, notable exceptions, and their craft and artistry have had a visible influence on the current year’s work. But many of the selections represented a larger trend in Australian filmmaking—innovative film form was waning, replaced with the mechanical tricks that cameras and editing software could do.

This year we are seeing something altogether different. It is by no means a return to the open-ended, raw experimentation of the first year. Every film is by a well-known artist or team, all have government funding in some form. No more are dancers waving cameras around—and so the wild flashes of brilliance that might have been sparked are gone, but they are replaced with accomplished artistry and a strong commitment to the integration of dance and cinematic arts.

Choreographer Julie-Anne Long and filmmaker Samuel James integrate danced ideas with cinema’s capacities in a loving homage to early film and the surrealists. Satiric, affectionate and funny, Nuns’ Night Out’s grainy black and white 8mm film stock, its stellar cast and its progression from oddball mundane to vaudevillian spectacle erases any trace of a boundary between the perfectly absurd and the perfectly normal, leaving both happily enjoying each other’s attractions.

The pair of films on the program by director-cinematographer Cordelia Beresford working with choreographer Narelle Benjamin are poetically gritty studies of 19th century psychiatric patients trying to reassert their sanity. In I Dream of Augustine the cinematic frame echoes the doctor’s clinical frame, and denatured textbook illustrations contrast with the living, breathing woman, personified by Benjamin, who moves through extraordinary, almost possessed, extremes. Beresford frames the moves unflinchingly, and then reframes the raging emotion with text on screen that gives form to multiple perspectives. The Eye Inside is more explicit on the subject of the authority’s voyeurism and their provocation of their patient’s displays. In this physically expressed version of a true story the wily victim escapes, exposing her ‘madness’ for the performance that it is and her salacious audience for the creeps that they are.

Tracie Mitchell’s Whole Heart is a moody and impressionistic story of a lone woman in an ‘Australian Noir’ outback. In between narrative sequences the woman moves through remembered or imagined locations, groping blindly, mixing her human frailty with decaying plaster, patterned paper and white light. Some of its story devices are rudimentary—a symbolic teddy bear, for example. But when it’s physical, Whole Heart reveals a stronger story; what the body remembers is given voice, light, shade and resonance.

Three Times by Sue Healy dances away from the edge of narrative. It’s a strong and sensual film, rhythmic, integrated and appealing. The polish given to the piece by Digital Pictures gives it a gleaming, almost fragrant luminance. Three Times also feels like an unresolved battleground between abstraction and narrative. It’s a formalist numerical premise articulated by leggy women in silky underwear behaving with an odd intimacy. The figurative within the formalist—an unresolved tension in much contemporary dance—is exaggerated here by cinematic craft that emphasizes character and style.

Alyx Duncan’s Pandora tackles narrative more directly, but falls shy of a strong story. It shows some of the best elements of its native New Zealand’s cinematic traditions—fantastical images and extraordinary textures—and ambitiously tries to bridge mythic ideas with naturalism in a loose and dreamy structure.

The collaboration between director Michelle Mahrer and choreographer Bernadette Walong uses cinema to envision the unseen. The cellular connection of sentient bodies and elemental nature permeates the layers of River Woman. The glowing images are of symbiosis—dissolved and superimposed minerals, flesh, water, light and movement disintegrate and re-form in cycles that speak to the grains of time, stone, earth and air in our own bodies.

By contrast, director Gina Czarnecki and choreographer Garry Stewart envision the body as one with its digital image, creating flows, sparks and rainfalls of sculptural bodies alive in image only. In Nascent, drips of slow moving forms stream across the screen revealing/leaving behind tangled figures like scars, etching spines or swarms, or slow motion ghosts. To quote poet Richard James Allen, “This is not falling, this is called flying.”

If any doubt remains about the efficacy of blending cinematic and choreographic arts, Shona McCullogh delivers the knock out punch with Break. Here the movement of a family shifts seamlessly from ordinary horsing around to extraordinary acrobatic articulations. Dance incarnates the manoeuvres and wounds of the psychological sword fights that slash at families’ bodies in this beautifully resolved balance of the abstract and the figurative, the narrative and the expressionistic, the cinematic and the kinesthetic.

I am confident that Break will bag one of the top 3 spots, and I have my money on Nascent and one of Beresford’s films for the other 2, but I rarely pick the same winners as the panel, so don’t take my word for it. It’s a program worth seeing for what it is and for what it might prefigure in Australian dance on screen.

–

ReelDance Awards, for Best Australian & New Zealand Dance Film or Video; One Extra, ReelDance, International Dance on Screen Festival and Tour 2006; The Studio, Sydney Opera House, May 5-7; see www.oneextra.org.au for national tour dates.

RealTime issue #72 April-May 2006 pg. 23