Dance impro: what's afoot?

Eleanor Brickhill

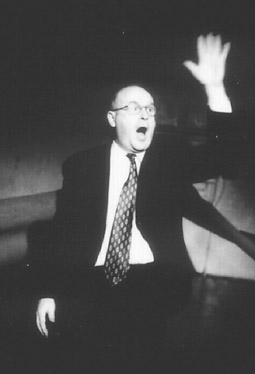

Andrew Morrish

photo Heidrun Löhr

Andrew Morrish

Is it true that Australian dance is currently undergoing a major resurgence of interest in improvisation as performance—or is it simply my personal bias towards the endlessly exhilarating environment in which I find myself? Whether true or not, the question has been pounced on by people from other major cities, not just on the east coast. Some say yes, some say no. While there are many people in little pockets around Australia who use improvisation in various ways, sometimes as a choreographic tool, or with scores around which a performance is based, these processes seem different from performance that is totally improvised—no scores, no structures, just-get-out-there-and-see-what-happens.

In Sydney there’s been a shift of focus, a critical mass of interest constellated by one or 2 events, notably Andrew Morrish’s performance project, Rushing for the Sloth, at Omeo Studios (Newtown) which had its inaugural performance early in 2000, and the Relentlessly On… performance season at Performance Space earlier this year, by Tony Osborne and Andrew Morrish (see RT#44 p37). Rushing for the Sloth is an ongoing forum curated monthly (the last Sunday of each month) which Morrish says “remains dedicated to the development of audiences interested in the potentiality of improvisational performance to create new form, endorse presence and embody openness.” He adds, “I’m not interested in having this conversation about what I’m responsible for, frankly. I’m just doing what I want to do, and that’s all there is to it. People improvise for a whole lot of reasons. Some people don’t need to get any better for it to work for them, and I’m very happy for that to be the case, but my own interest is in making increasingly interesting theatre.” With this aim in view, the intervening Sundays function as more intimate forums (Taming of the Sloth) for a core group of 5 to 10 practitioners and invited guests to develop skills, pushing themselves to expand their range of material.

Melbourne practitioner Martin Hughes (State of Flux) asks how I might be assessing this so-called resurgence. “Who is it showing all this sudden interest? Clearly we are talking about a very specific population. The popularity of Morrish and Peter Trotman, who for more than 15 years have been able to find audiences, attests to a long-standing interest in improvisation as performance. Theatre Of The Ordinary, Al Wunder’s performance group, has operated for more than 20 years. And witness the huge interest in Deborah Hay’s classes recently. I believe this could only be possible with a history of practice for many years prior to her classes. Ros Warby is another name that comes to mind [see interview RT#46, Dec, 2001], someone who has a long history of exploring improvisation as performance.”

Most certainly improvisation has a history, though for a long time government grants were reserved for purely choreographic endeavour. Perhaps, wisely, the word ‘improvisation’ has simply been absent from the discussion even if it was present in many people’s practice. In the early 1980s, Dancelink invited a number of American improvisers to Australia to teach and perform, notably Steve Paxton, Lisa Nelson and Dana Reitz. The development of ongoing mentoring relationships with international artists has continued, more recently with further visits from Deborah Hay, Lisa Nelson, Jennifer Monson, Eva Karczag, Julyen Hamilton and Ishmael Houston-Jones, to name a few, and many Australian artists discuss their relationship to these people as primarily important in their artistic development.

Adelaide artist Helen Omand suggests that improvisation holds an interesting mirror to current political changes, in that the autocratic creator is now going by the wayside. In Steve Paxton’s view (“The History and Future of Dance Improvisation”, Contact Quarterly, Vol 26, No 2, 2001) governmental regimes have changed from controlling forces which expect their populations to do as they’re told, to ones which expect their populations to take responsibility for making their own work. Further, Paxton writes, “Since the recent popularity of chaos theory, chaos has been rationalised, seen to have structure, and proves to be metaphoric of sensitivity rather than insanity. It has been upgraded. It is invited to the dinner table, and shows up at dance performances.”

Ryk Goddard, artistic director of Hobart’s Salamanca Theatre Company, discusses what’s afoot: “The scene is very young here, but there are already crossovers occurring between dance and theatre performers, underlying the strength of the scenes in Melbourne and Sydney. The new improvisation is not pure, but hybrid, collaborative and fuelled by curiosity. It’s built around practitioners like Wunder, Morrish and Helen Clarke Lapin, who have stayed with the form since the 1970s. Contemporary practitioners are no longer trying to shock or smash the system but are engaging in a genuine exploration, and this moves it from a training or developmental tool into a performance form in its own right.

“The forms reflect social structure. The 4-act play, for example, reflects a classic, 1950s-style school-marriage-career-retirement social order. In the 1970s when these structures were being torn down, improvisation became a tool to do this with. In the 1980s, Theatre Sports became the ‘accessible’ art, and suited the prevailing culture that said that even art could make money. Unfortunately the make-or-break quality meant that performances were sometimes based on cleverness rather than genuine exploration. Now, people move relatively quickly in and out of different countries, institutions, employment. We are better at multi-tracking, allowing creativity to sit beside business, including imagination in intelligence.”

Goddard established Eat Space in Hobart, teaching performance improvisation focusing on ensemble, solo or duet. He teaches movement, voice and text skills, examining different ways to create scores or lines of enquiry which shape performance. Two students have set up Blink, a monthly performance improvisation laboratory, like Sydney’s Sloth, on the last Sunday of every month. People have very different interests and performing styles, and because the scene is new, performance times are short (5 or 10 minutes). As people become more skilled, times will become more flexible.

Morrish drew a schematic diagram of names, with circles and arrows going from one to another, trying to explain all the relationships that, in his view, create the complexity of Australian improvisation culture. A central name in his scheme is Al Wunder, Melbourne teacher and practitioner, often mentioned as the most influential artist in Australian dance improvisation, if not directly then via his students, some of whom now teach and perform internationally.

In 1962, the only performed improvisation Wunder knew about was jazz music. Later, his growing pleasure in watching improvised class exercises fuelled the idea of totally improvised dance performance. At Judson Church in New York this was already happening, and contact improvisation was born out of this. Contact has traditionally been based on the development of physical skills—particularly partnering skills where 2 people move around an ever-changing point of contact—and as a response to the high dance culture of 1950s and 60s USA. Meanwhile those skills continue to be refined in a variety of performance contexts, in choreographic endeavour (eg DV8in the UK) and improvisation of all sorts.

For Wunder, there is little similarity between his work and traditional contact improvisation. He encourages people to use any and all of the performing arts—music, all kinds of dance, theatre—as a means to communicate to the audience. Most people believe it is the non-competitive nature of his style of teaching that has proved so popular. His teaching methodology deals primarily with physical awareness and articulation, but essential to this is the idea of positive feedback. “Whenever we talk about exercises or performances, we state what we enjoyed doing or seeing and try to say why we enjoyed it. This gets rid of the negative judge and fosters confidence in both performing improvisation and developing one’s own aesthetics.” Martin Hughes thinks this is fundamental to what happens in Melbourne, engendering a very positive environment for exploration that goes well beyond the classes and is evident at many performances, strongly supporting Melbourne improvisational performance practice.

Melbourne in particular has hosted a number of the now very popular ongoing improvisational performance forums, beginning with The Flummery Room, set up by Morrish and Peter Trotman, which flourished for several years. According to Hughes, this kind of ongoing forum has been very much led by the example of Trotman, Morrish and the group Born In A Taxi, providing performance opportunities for themselves whenever they had the need to test out their latest exploration. In similar style, the monthly improvisational performance forum, Conundrum, was initiated by 2 groups, Five Square Metres and State of Flux. Running for 6 years, these nights now have a minimum audience of 80 enthusiasts.

Five Square Metres base their work on ‘school of fish’ ensemble movement, storytelling and character creating a collage of imaginative, abstract performance, a theatrical world that closely resembles a way of life. Pieces range from 25-35 minutes. State of Flux play with scores and structures, but also use no scores to find new territory. Classes focus on contact skills, but their overt aim is to explore the ‘performability’ of contact, enhanced by the diversity of skills in the group.

Born in a Taxi have found audiences and income in the corporate market, bringing theatre practice to movement improvisation disciplines, creating forms of improvisation that balance entertainment with genuine exploration and imaginative licence. Theatre of the Ordinary, Wunder’s performance group, is based at Cecil Street, Fitzroy. Hughes and his partner are responsible for running the Cecil Street studios, and maintain a diverse range of improvisation classes.

Jo Pollitt, Perth artist, found inspiration in her experience of the huge New York improvisation scene in 1999. Her performance/research group, Response, began in March 2000 with 14 dancers, retaining a more workable number of 5. With a visit from Jennifer Monson from the US last year, they have also developed a working relationship with an improvisational orchestra, Ensembleu. Pollitt teaches improvisation at the West Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA), and from time to time holds increasingly popular ‘quick response’ lunchtime improvisation sessions. “In terms of dance, I definitely feel like I am pretty much on my own here in Perth, although I am very supported at WAAPA and have no trouble finding interested dancers to work with.” Recently, Perth performers Tony Osborne, Alice Cummins and Jonathan Sinatra have moved to Sydney, and along with Morrish’s move from Melbourne, have enriched the Sydney scene immeasurably.

Pollitt’s interest is in “the potential energy and the value of the body and the person, in light of the glut of new technology, today’s cyber-infused world, and dance-theatre inspired work. Is the body still interesting to watch in itself? I think dance improvisation in performance can offer a precise and non-linear insight into the performer. Humans are complex and it is this I hope to reveal through dance, in the performers’ choices and responses.”

Helen Omand in Adelaide has found that although there are improvisation practitioners there (rumour has it that there’s yet another group called Eat Space), it is still mostly an unknown, little understood form in the dance community. She began teaching classes on returning from Europe late last year although student numbers were low. “Kat Worth and I have been inviting different people to jam with us, but this has also proven slow; professional dancers are so busy, juggling paid jobs and grants. We are still looking for the right form for things to take off.”

Omand says, “Everything in nature forms patterns. In fact, the biggest fallacy about improvisation is the idea of freedom. You cannot be free if you are not placed and present. To be able to make choices, you first have to ‘know’ where you are. Then comes the ability to be open to the realm of possibilities, choosing whilst maintaining presence. The best improvisations are when it seems like the score has already been written in space/time, and the body makes it manifest.”

Similarly for Goddard, contemporary improvisation is all about form. It’s about learning how to recognise the dynamic you are in to bring out its richness. If you expand the moment enough, ideas and themes emerge and become recognisable. “At its best—and there are many great practitioners—it is satisfying, demanding performance that is honest, reflects in its energy the way people live their lives, and allows the coming together of imagination, the body, the intellect, humour and grace.”

Thanks to Al Wunder, Helen Omond, Ryk Goddard, Andrew Morrish, Martin Hughes & Jo Pollitt for their generosity in contributing ideas to this article, and to the many improvisers whose ongoing practices have made the vibrancy of the scene worth talking about.

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 11