Dancing away with the Dendys

Erin Brannigan

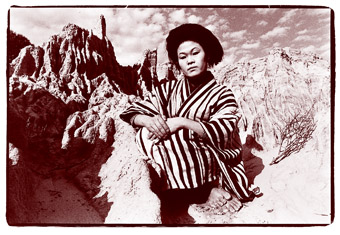

Yumi Umiumare, Sunrise at Midnight

The 3 finalists in the General category at the Dendy Awards this year—Blowfish, Sunrise at Midnight and In Search of Mike—all involve dance practitioners. Neither fiction, nor non-fiction, these films sit somewhere else amongst the traditional categories of cinema, probably most closely affiliated with the historic avant-garde. Dancers or choreographers and filmmakers who have previously worked with dance are the only characteristics these 3 shorts have in common, and each needs to be considered for its very individual approaches to the short film format.

Sunrise at Midnight, featuring Melbourne dance-makers Yumi Umiumare and Tony Yap and directed by Sean O’Brien, is a cinematic study in the most poetic mode. Introduced by Umiumare in voiceover as she makes herself up in traditional Japanese style, the film is based on the story of a troupe of female Japanese performers who travelled around Australia early in the last century, and a woman who lost her way in the desert. Shot in black and white, it recalled the pace and certain attention to texture in the producer Sophie Jackson’s early short, Swing Your Partner, which featured a middle-aged couple in their wedding clothes dancing to a country love-song. While that film focused on the rhythm and progression of the dance, Sunrise at Midnight focuses on the stasis of the characters as much as, or perhaps even more than, their movements. Umiumare and Yap both have Butoh backgrounds, and this aesthetic is ingrained in—almost in the grain of—the film. The peculiar and terrifying darkness of the Australian outback collides with this Asian dance method to literally and effectively illustrate the story which is at its heart; a Japanese woman alone in a landscape that is intensely foreign and cruelly unforgiving.

But this simple reading of the film doesn’t really stick, and it’s the temporal dimension that squeezes more out of the situation depicted. Umiumare has spoken of Butoh as a dance of darkness but more than that, a journey through the darkness toward the light. The Japanese character doesn’t appear to be fighting or struggling with her situation, but absorbing it and experiencing the landscape she finds herself in, almost becoming a part of it through the framing of the camera. The appearance of another figure (Tony Yap) doesn’t break her isolation but oddly fills out the environment.

South Australian choreographer and dancer Tuula Roppola co-directed and stars in a film that can be more simply labelled a dancefilm due to its style and content. Blowfish features a solo performance by Roppola (if you don’t count the rubber blowfish) accompanied by a voiceover describing, in very banal terms, her actions. She works mainly against a wall and is framed quite tightly so that her physical articulations are very much at the centre of the film. The stop-motion creates an affect where the transitions from one position to another are elided and Roppola appears to be moved by an exterior yet invisible force. European filmmaker Pascal Baes had great success on the dancefilm circuit some years ago using this technique in his films Topic II and 46 Bis which featured dancers gliding down the streets and around courtyards in a bizarre and muted ‘dance.’ Baes went on to make ads for the Philip Starck hotels which featured a weary traveller gliding into a hotel foyer, up the stairs and into bed.

Roppola’s film, co-directed by Ian Moorhead, doesn’t really do anything new with this technique, but Roppola’s performance is compelling and her apparent lack of agency evokes a characterisation of sorts—a woman who is merely going through the motions, or, moved by another’s commands.

The winner of this category and the overall winner of the Dendy Awards, Andrew Lancaster’s In Search of Mike rides across a variety of forms or genres from music video to dancefilm, fictionalised documentary to queer screen. Writer/performer Brian Carbee (see interview, RT41 p27) plays himself and his mother—both young and old—in a bravura performance that is the real heart and soul of the film, even though objects, characters and domestic spaces (bedroom, kitchen, loungeroom) have almost equal resonance throughout. This film conjures the temporal shape of its story through its material details: a doll, a cowboy dress-up set, an oxygen tank, a set of false teeth. These objects stand out against an environment that is at once recognisable and then a surreal any-space where the young and older versions of the male lead overlap in a succinct coming-of-age scene. This particular scene features the only dancing per se, and even this is more like a cross between a tantrum and a frenzied nightclub scenario. The skills of Carbee the dancer and choreographer can be found more in his regular actions—dressing, sitting, gesturing while on the phone; there’s a kind of grace and ease there.

And then there’s the language. Lancaster has spoken about his interest in creating films to existing or specifically devised scores, for example his videoclips for Custard, Lino, You am I and Midnight Oil and his soundtrack driven shorts Palace Café and Universal Appliance Company, and has described the appeal of Carbee’s voice and script to his aurally-obsessed tendencies. Carbee’s grainy tone and American accent and his rhythmic writing style combine with a film score by Lancaster’s band Lino, to add another level to the film that is as rich and varied as the visuals. Carbee’s skill in evoking the intriguing character of his mother through her words may be inherited. In the film he says: “My mother doesn’t so much turn a phrase as flip it on its back and fuck the shit out of it.” Combine this kind of talent with Lancaster’s innovative and eclectic approach to short filmmaking and you’ve got yourself a winner.

Dendy Awards, opening day of the Sydney Film Festival, State Theatre, Sydney, June 8.

RealTime issue #44 Aug-Sept 2001 pg. 35