Degendering

Keith Gallasch: Motus, MDLSX

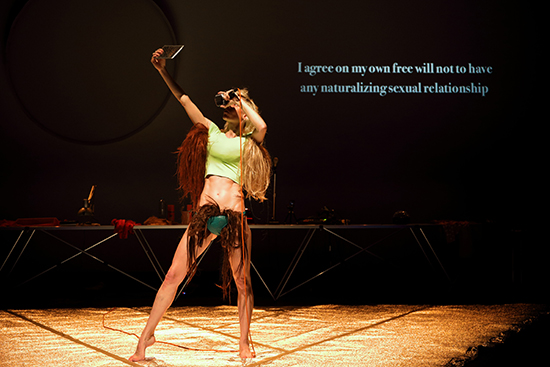

Silvia Calderoni, MDLSX, Motus, Adelaide Festival of Arts 2017

photo Tony Lewis

Silvia Calderoni, MDLSX, Motus, Adelaide Festival of Arts 2017

“I’m tired of being asked if I’m a man or a woman. This should never be the first question. There are other questions.” Silvia Calderoni

Transgenderism is increasingly visible in art, popular and celebrity culture, activism and everyday life. The Italian performance company Motus’ MDLSX addresses the subject via the life of one of its ensemble members, Silvia Calderoni. Director and dramaturgs (including the performer) merge incidents from childhood to early adulthood with material from Jeffrey Eugenides’ best-selling 2002 novel Middlesex, in which the central figure is a boy, Cal, raised as a girl, Calliope, by parents unaware they’d had an intersex child. Co-director Daniela Nicolò says of MDLSX, “It gives a lot of information about intersexual people, even technical information. This is, for us, important.”

Publicised as a party, MDLSX is a far from didactic work. I felt like the guest of an enigmatic host who, averse to eye-to-eye contact, DJs (The Smiths, Dresden Dolls, Vampire Weekend etc), dances furiously, obsessively self-videos and constantly changes outfits—male and female—as if I weren’t quite present but still desperately needed.

A sound system, lighting controls and video camera sit on a long table before a wide screen on which, to the left, hangs a metre-wide disk showing family videos; to the right, surtitles for the many moments when Calderoni interrupts frantic activity and soundtrack with lucid unemotional recollection, commentary and quotation. The desire to communicate is passionately felt and vigorously conveyed in free-form dance and changing guises, but otherwise laterally realised via a technological arsenal. Well into the performance, Calderoni’s face is obscured, seen only on the disk screen via video camera.

Calderoni says MDLSX is not therapeutic for the performer, but the work is clearly engineered to drive through social and ideological barriers to a cathartic climax of personal release and familial conciliation. It’s also one in which the subject of the work has apparently total control over the means with which an ambiguous state of being is conveyed to us and a search for resolution pursued.

The first video we see is of an 11-year-old Calderoni, “a little girl always mistaken for a boy,” singing badly on microphone. It’s funny but disconcerting, the first glimpse of a string of escalating pressures, anxieties and compensatory behaviours: invasion by “mother’s brutal” camera; lack—no breasts, no penis; female friends “a different species;” bra-stuffing and a faked explosion of pubic hair; a frightening visit to a clinic for assessment and possible gender reassignment; and the ultimate fear of being labelled an hermaphrodite, eunuch or “monster.” Legs wide, genitals bared, a fraught Calderoni casts a laser beam body-length, dividing an unresolved self in two.

When escape from family becomes a necessity, Calderoni (like Eugenides’ Cal) runs away and performs in a cabaret ‘freak’ show—as a glittering mermaid (Cal a hermaphrodite)—but finds adjustment to a male world and the association again with the “monstrous” complicated. But there is pleasure: video-ed in a hotel room, Calderoni revels in dressing in a svelte cowboy-style suit and hat.

Gorgeous flowers slowly open on the screen, their stamens suggesting beings at once male and female, their projections spilling out around the hitherto containing disk—”I was no longer in the mirror.” The final image, another home video but not a constricting one, is of a smiling Calderoni, boyish, hair tightly cropped, dancing casually with a reconciled father. But it’s the mature being I’ve witnessed onstage and seen in the media, swinging between male and female appearance, who more fully represents gender transcendence, if not always granted it.

Silvia Calderoni, MDLSX, Motus, Adelaide Festival of Arts 2017

photo © Simone Stanislai

Silvia Calderoni, MDLSX, Motus, Adelaide Festival of Arts 2017

“I’ve had the question all my life. Some days it is painful. Other days it’s not a problem. It is my life. I don’t want it to define me. Sometimes I dress like a man, sometimes like a woman. I don’t want a label or a classification.”

Personal pronouns are gender labels, hence “non-binary” transgender people ask for “they,” “them” and “theirs” to represent them in the singular, which can be grammatically and logically confusing. I challenged myself to write this review without recourse to “he,” “she” or “they.” It wasn’t easy. In the print version of the Sydney Morning Herald interview quoted in this review, Daniela Nicolò says that company members refer to Calderoni with feminine pronouns without causing offence, but I suspect that a context of familiarity and friendship explains that. It’s clear that our lexicon is undergoing a huge change as gender barriers are progressively broken down.

The complexity of the personal, cultural and linguistic transition is epically surveyed by Jacqueline Rose, in a mind-bending essay about inter- and transsexuality in the London Review of Books, in which the writer cites a range of terms listed for a conference on transgenderism—”non-binary, gender queer, bigender, trigender, agender, intergender, pangender, neutrois, third gender, androgyne, two-spirit, self-coined, genderfluid.” Also quoted is an observation from a psychoanalyst: “you will meet persons who could be characterised, and could recognise themselves, as one—or some—of the following: a girl and a boy, a girl in a boy, a boy who is a girl, a girl who is a boy dressed as a girl, a girl who has to be a boy to be a girl.” Binary distinctions become fraught and nouns as well as pronouns rendered unstable.

MDLSX can only convey limited information, including excerpts from audio interviews with specialists and technical content from Eugenides’ novel, which caused consternation in transgender and professional circles for its attributing Cal’s intersex status to the genetic consequences of incest—not an issue in MDLSX. For those who haven’t thought much about transgenderism nor met transgender people, MDLSX, as intended by the artists, is a trigger for learning and empathy as we watch a driven personality create a narrative that asserts and celebrates (hence the frantic partying) a state of being beyond conventional notions of male and female.

Transgenderism has long been kept secret and often subject to punishment if revealed. In MDLSX, a child’s confusion and shame, and an adolescent’s quests, revelations and determination are mapped out such that we witness a more than personal, cultural escape from ignorance and secrecy, such that Silvia Calderoni can stand naked before us, our eyes meeting.

Quotations are from a Sydney Morning Herald interview with Silvia Calderoni.

Silvia Calderoni, MDLSX, Motus, Adelaide Festival of Arts 2017

photo © Simone Stanislai

Silvia Calderoni, MDLSX, Motus, Adelaide Festival of Arts 2017

Adelaide Festival 2017: Motus, MDLSX, performer Silvia Calderoni, directors Enrico Casagrande, Daniela Nicolò, dramaturgy Daniela Nicolò, Silvia Calderoni, sound Enrico Casagrande with Paolo Panella, Damiano Bagli, lighting design, video Alessio Spirli; AC Arts Main Theatre, Adelaide, 10-13 March

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017