Degrees of pathos: Sydney performance

Keith Gallasch

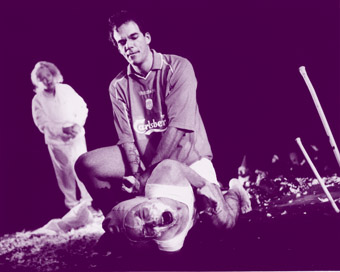

Lynette Curran, Socratis Otto & Matthew Whittet, Fireface

photo Heidrun Löhr

Lynette Curran, Socratis Otto & Matthew Whittet, Fireface

Theatre director Richard Wherrett’s autobiography has just been published, his direction of the Johnny O’Keefe musical, Shout, acclaimed, and he’s been given his own slot in the Radio National breakfast program. And he’s made a speech. Wherrett has witnessed what he thinks is a malaise in Australian theatre, “a terrible deception, a monumental con, a giant fraud”, that “from the moment we enter the yawning chasm (sic) of the auditorium we seem to enter a willing conspiracy that what will follow will be an event of great pith and moment, and seriously important to our lives. That it ought to be is beyond question. That it is is far from the case.”

Wherrett’s hit and miss assault on standards in theatre practice, writing and reporting at the National Performance Conference (January 19; edited version Sydney Morning Herald, full version smh.com.au, Jan 20) grabbed sizeable media attention, generated an odd collection of letters to the editor and sound responses from playwright Beatrix Christian and PACT Youth Theatre’s Lucy Evans in the Sydney Morning Herald’s open access commentary spot, Heckler. Doubtless, like provocations from Barrie Kosky, John Romeril, Katharine Brisbane, Robyn Nevin and others in recent years on a variety of platforms, Wherrett’s call for rigorous public debate will evaporate into the arts ether. A major reason for this is not necessarily artist or public indifference to the seriousness of some of the issues raised, but the absence of any sustained debate about them in the press, on radio and especially television. The infotainment era doesn’t encourage extended argument. These passing storms are quickly forgotten, usually until the next round of Rex Cramphorn or Philip Parsons Memorial lectures.

This is not to say that these surges of critical energy don’t share, at least on the surface, some common motivation, or solutions: Kosky has railed against the preoccupation with funding at the expense of vision; Brisbane and Jack Hibberd have proposed moratoriums (5 years I think) on funding in order to reinvigorate Australian arts; and Wherrett, while proposing we take to the streets to demand more arts funding, suggests we “ban all new Australian works from the stages for 5 years with the note ‘write better.’” He says funding is not the issue but how it is spent. Beatrix Christian retorts: “…Wherrett, like many Australian theatre practitioners, considers the act of playwriting as a thing apart. It’s not. Ultimately, playwrights become as provocative, ambitious and compelling—and as technically polished—as their theatrical culture allows them” (SMH, Jan 23). Asked by The Australian to detail his solutions, the banning of new plays was not mentioned, replaced it seems with a call for “separate funding for research and development wings” for companies (something that several flagship companies are already embarking on). “If the plays are finally not up to scratch, then they should not get done” (The Australian, Jan 19). Who’s to decide this—cultural commissars clutching 5 year plans in the guise of Wherrett-like gents of good taste?

Wherrett also proposes audience size as a significant criterion for funding: “I would propose any company or project reaching audiences of less than 60% per performance be carefully reconsidered” (The Australian). What then are we to make of this proposition from his address: “If you compared the Railway Street Theatre Company, Griffin, Sidetrack and Urban Theatre Projects in terms of actual dollar assistance in relation to the number of performances mounted, the size of the audience reached, and the resultant value for money in terms of subsidy per seat, you would find huge discrepancies.” Is that surprising? What is the cost of innovation? What is the cost of developing new kinds of theatre for regions and communities and for artists who work outside the mainstage, and for nurturing writers? Had the seminal Australian theatre of the 70s been assessed on audience numbers, where would we be now?

I have to say that I wearied quickly of people who enthused, “Good on Richard Wherrett. At last someone’s come out and said what had to be said.” “Which bits of what he said or do you really agree with all of it?” I’d ask. The particular impact of Wherrett’s wide-ranging tirade is, I think, because of its specificity. He names names and he names shows. This is not common to such speeches. There are things you can agree with, like the disgrace of Leo Schofield’s Olympic Festival, bereft of new Australian theatre works (and much else), the limits of much arts journalism (“How can two of our major arts journalists spend months of valuable column space obsessively speculating on the successor to the Australian Ballet”), his disapproval of certain productions, and the need for the arts community to unite on the demand for more funding. However, his call for “rigorous, selective and artistically assessed assistance” is as abstract as that which he condemns : “I feel there is at work, federally and statewise, principles of criteria for support that are dangerously idealistic, abstract, indefinable, and worst of all politically determined…” Wherrett’s calls for the return of heart over head in direction, for “thematic potency”, for the need to “entertain and uplift our audiences” and “the experience of shared communion,” evoke a cozy, cliched humanism, a dream of one theatre without the tiresome diversity that enrages him: “Should political correctness, which I assume is driving the STC’s selection of women directors, be banned?” Wherrett argues strongly for more funding, but the very absence of it allows him to deplore “spreading the jam too thin.” If empowered would he give out all the funds if they became available? I doubt it. His agenda is clear. Wherrett’s speech really adds up to little, a flurry of vagaries, dislikes (the things he would banish), abstractions about what he wants of theatre. There’s no vision here, just blind swipes. The end result is pathos, all that fury expended, signifying little. You know that when you ask yourself, “what exactly am I being rallied to do?”

All this, just when I’ve been enjoying going to the STC more often, sensing excitement, experiment, intelligence. And getting it, mostly in the Blueprints program, not always agreeing with the outcome, but unlike Wherrett not expecting every visit to the theatre to change my life forever. As I argued in RT#41 (“Plight of the New”, p26) there are many different kinds of experience to be had in the theatre, something confirmed by a group of innovative performances I’ve witnessed over the last 2 months in various venues. Not surprisingly, given the dated frame of reference Richard Wherrett springs on his audience, there’s little room for these kinds of work in his sorry vision.

Sydney Theatre Company, Fireface

The rare pleasure here is of seeing a recent German play, Paul Von Mayenburg’s. Fireface. Benedict Andrews’ intense production provides a voyeuristic widescreen theatrical experience, an irregular letter-slot view of family life, so confining that even the family has to stoop at one constricted end of the stage (designer, Justin Kurzel, lighting Mark Truebridge). A huge space behind, a pit inhabited by a multitude of fluffy toys lit with day-glo brilliance, is only ever the point of entrance and exit for the brother and sister who leap or crawl in and out of it, an evocation of the borderline child-adult place of these incestuous siblings where neurosis can and does become psychosis, passing from one to the other like a virus. This is serious pathos. There are no tragic insights, no room for sympathy, a little for empathy. We watch the spread of an appalling condition. It’s in their solo moments of raging pleasure that we recognise release and transcendence—the voice of the sister (Pia Miranda) pitches up and a tear winds down a cheek as she gives voice to the absolute pleasure that pyromaniacal conspiracy has unleashed in her. The brother (Matthew Whittet) is a crazed visionary (obsessed with his birth, the very moment of it), an irredeemable Hamlet (“you’re a mother, don’t try to be a woman”, he screams at his naked mother in the bathroom); his madness is simply inexplicable. His parents might be obtuse and ordinary, but there’s nothing to blame them for except their failure to recognise the monster in their midst, who’ll hammer them to death and await his own immolation, regretful that he ever needed his sister’s complicity.

Although a play from a new generation of German playwrights, this is theatre that seems to merge a Franz Xaver Kroetz family, a disoriented individual out of Botho Strauss, a Fassbinderish perversity and fatalism with an unpredictability common to all 3. True to all of these writers, the mise-en-scene is bizarrely cinematic. Matthew Whittet is physically and emotionally frightening as the brother, Pia Miranda provides just enough normalcy in counterpoint, Lynette Curran and Anthony Phelan play the parents with restraint (shorting Von Mayenburg’s satirical instinct) and dignity, and Socratis Otto is the sister’s boyfriend, the right mix of sensitive and obtuse, embraced by the parents. Not everything works: there’s a mix of playing styles most evident in vocal delivery; an excess of entrances and exits, especially by the parents, kills some of the cinematic drive; and the ending is muffed. Is Fireface the last instalment in a Benedict Andrews trilogy about identity and morality—the experiment with innocence in La Dispute, the invention of a life in Attempts on Her Life (including the imputed evil of the terrorist Anni) and the fundamental evil of the brother in Fireface (circling us back to La Dispute)? It’s been a fascinating inquiry, boldly conceived and directed, and without concession to the dogged demands for heart and sympathy called for so often these days, as if the recognition of otherness and the sheer struggle to understand identity stand for nothing. Wharf 2, Sydney Theatre Company, opened Jan 6.

PACT Youth Theatre: Pre-Paradise

Just as impressive in its own way, if more innocently performed by its cast of 15-25 year-olds, is Caitlin Newton-Broad’s finely crafted production of the Fassbinder-derived and inspired Pre-Paradise with dramaturgy by Laura Ginters, I have distant memories of seeing/hearing about productions of Pre-Paradise Sorry Now in the 70s, but more familiar here was the sense, if not always the actuality, of characters and situations from Fassbinder’s prodigious film output, brief melodramas here played larger than life: the story of the woman socially maligned for marrying a migrant worker, a misogynist butcher in desperate need of affection (he talks economics to a doll), seriously disturbed upholders of the law, ruined soldiers and repressed homosexuals. Here they are fragments of characters in a turbulent milieu, self-possessed, barely aware of each other, perpetrating and battling the tyrannies of common sense (invoked by giggling children at beginning and end as a kind of geometric certainty) and unfathomable personal drives (“I like myself and won’t let anyone get in between”). Common sense rules, embodied in appalling cliches and double-bind killers: “You’re beautiful. Beauty doesn’t last.” At the centre of the social whirlpool is an innocent, an alien, Phoebe Zeitgeist, not unlike Handke’s highly abstracted Kaspar. Because she has no language, she is not seen (like the hero of Patrick Susskind’s Perfume who emits no smell) and is free to witness human society. She collects the sayings she hears perpetrated on others and innocently turns them on society. Shorn of their everydayness and the familiarity of family knots and the catch 22s of love, the commonsensical utterances kill—society falls down dead, murdered not by an alien, but by itself, by language. Fiona Green makes a very good Phoebe Zeitgeist, even if the mapping out of her journey is not always as clear as it could be. The cast vary enormously in talent but Newton-Broad and her collaborators (Regina Heilmann and Chris Ryan) somehow draw emotional, if not always physical, conviction from the least likely performers. Movement is boldly choreographed, only the absence of a coherent vocal strategy detracting from the force of the work, but Fassbinder’s overarching fable is always made rich by the moments of social observation and Brechtian wit, and not least by the terrible sadness at the core of these earthlings’ lives, the pathos that they know no other meaning. PACT Theatre, Nov 23- Dec 9

Urban Theatre Projects: Manufacturing Dissent

Fireface is a relentless hypernaturalistic portrayal of madness in a family scenario. It demands attention to experiences beyond our own. For all its dissociative and distancing elements it remains recognizably a play. Pre-Paradise is a fable packed with quasi-naturalistic micro-narratives, 60s/70s pre-revolutionary (pre-paradise)—the enemy is ourselves, not simply the state or the family, and can be found in our voices, embodied in us in language. The play itself is no longer revolutionary, that moment has passed, but its strangeness still acts on us and its moral is felt. The experience is not of seeing a museum piece, though at times Broad’s refusal to pervasively contemporise it made me feel at times that we were supposed to be admiring a classic. In an utterly different way, Urban Theatre Projects’ Manufacturing Dissent evokes and reproduces classic manifestos and performances from the 20th century history of the theatre of opposition while returning again and again, with grim contemporaneity, to the plight of the refugee. This is theatre as essay, a discursive, chatty talkshow of a performance at a very long desk (with microphones and texts a la the Wooster Group) where performers can drop in and out of various personae, address us directly, turn inward, histrionic, comic, pathetic. They read manifestos aloud, turn jury, enquiry, newsreaders, singers, slipping deftly in an out of roles that occasionally evoke characters who might return later (or not)—like the woman who, alone at a microphone, struggles across the evening to sing a song (is it Vietnamese?) full of pathos…and finally does. I don’t know what she’s singing, but it sounds nostalgic, full of yearning and, finally, release.

A friend, who knows about these things, tells me a few days later that nostalgia is a serious business. It was once recognised in 19th century Europe as a psychological condition that could kill—people died of nostalgia. It was common to soldiers and invariably it was tied to the loss of homeland.

For those in the know, Mayakovsky, Brecht, the Living Theatre, Boal, Community Theatre, Müller, all make their appearances one way or another in the course of the show, sometimes facilely (the sorry evocation of the Living Theatre), sometimes cheaply (a nonetheless hilarious litany of the buzz words of 80s community theatre), sometimes painfully (the revolutionary theatre company with their wooden guns who can’t spill blood when it comes to the crunch). The show’s multimedia dimension includes Philip Ruddock’s favorite—video footage of Australian wildlife and deserts sent out as a deterrent to would-be refugees. (Brenda L Croft, at a PICA-Perth Festival forum, apparently said she wished Indigenous people had had that tape 200 years ago.) And there are moments of provocation (familiar to some, a surprise to most): a woman performer asks, begs, demands someone from the audience spit on her (no takers this night, but some on others). Throughout, a man (Woody Chamron) in a wire cage with a potted palm (evoking Australia’s refugee detention centres), has been sitting with his back to us watching the Olympics on television. At the end he introduces himself and tells the story of his escape from Cambodia. He says we can leave at any time. But it’s hard; even though his story seems interminable (if finely delivered), it would be like spitting on him. What is interesting is that he is presented as real, he plays himself. And that he’s not an unhappy refugee. He’s home, though it’s no longer Cambodia. There’s hope. Well, there was once for refugees to this country.

Manufacturing Dissent sets itself a tough task, one which sometimes sets it teetering on the edge of impotence and cynicism when rattling superficially through the history of radical theatre; the performers don’t always seem at home with their material; and the show occasionally loses its shape and momentum (the potential of the team at the desk hasn’t been realised). But Manufacturing Dissent has stayed with me because of its insistent questioning about how to make performance as protest and how it manages to walk the fine line between accessibility and challenge, embracing an audience largely unaware of a (predominantly Western) tradition of resistance in the theatre. But it was the topicality of the refugee issue in Australia, the directness, humour and anger with which it was addressed that kept open the possibility of theatre as protest. Made by the UTP Performance Ensemble with John Baylis and Paul Dwyer. Director, John Baylis. Performance Space, Nov 30- Dec 10.

De Quincey Etc: Walking Species 1

Three women in raincoats walk the perimeters of the room, each at her own pace, in her own time, until we absorb their rhythms, glimpse images and texts on small video monitors in corners, a landscape projection on a wall (finally an electrical storm), absorb sounds—from the swish of coats, feet, Wade Marynowsky’s score. Rhythms change, the trio intersect, speed becomes collective, the bodies almost in competition to hold the space. The raincoats, worn reversed, are now right way about and open, the bodies naked, self-contained, the journey as insistent as ever, even if it goes nowhere but in and out of itself—or is it a space being claimed, and we, the audience, intruders. The facility of performance to evoke states of being (in contemplation, under physical duress, both here it seems) is nowhere more evident than in this kind of work. Although as yet lacking the definition and certainty of their director’s famed movement (De Quincey doesn’t appear in this show), the performers (Tina Harrison, Victoria Hunt, Marnie Georgiette Orr) move with such purpose and focus that their quest is convincing. Emerging from the second instalment of her Triple Alice project, De Quincey connects the performance in the end with the Irati Wanti campaign by Indigenous women to prevent their land being maintained as a radioactive dump (a legacy of the Maralinga bombs). Then other meanings flood back across our memory of the performance. Artspace Offsite Event, Imperial Slacks, Sydney, Jan 5-7.

–

RealTime issue #41 Feb-March 2001 pg. 23