Doing a Foreman

Keith Gallasch: Kitchen Sink, My Head Was a Sledgehammer

My Head is a Sledgehammer

Heidrun Löhr

My Head is a Sledgehammer

Foreman has to be seen to be believed. Limited to reading about his Ontological-Hysteric Theatre for decades, finally in London in 1997 I saw and believed. Foreman and company were in town with the trademark set–a work of art, black and white perspective lines, props displayed as if from an eccentric collection–along with the admired narrative discontinuities and undoing of ‘character’ which Richard Foreman shared with other New York performance notables of the 70s. It was thrilling to see it all in 3-D. But belief had to sustain a few jolts. This was an even more intensely visual experience than expected–by the end of the performance the set had been re-worked, every prop exploited, perspective re-aligned. Whatever else they were doing, the performers were executing an artwork. A more electric and discomfiting jolt was provided by Foreman’s excessive theatricality. In the early 80s I’d seen works by Mabou Mines, Meredith Monk and Robert Wilson where the revolution against the conventional in theatre, dance and opera had been realised as a startling spareness, time distended, the body foregrounded, language undone, an intensely visual experience. Here I was witnessing something furious, fast, bigger than life that seemed on the one hand kind of old-fashioned, on the other radical, since the over-the-top theatricality was not sustaining the verities of plot or character, but something else altogether, a curious admix of the visual and a disjunctive psychology of displacement, condensation, slippage. It was funny, bewildering, disturbing.

It’s one thing to read that Foreman is funny, it’s another to experience it. It’s funny funny. It’s funny in bits, in the Woody Allen manner–waves of one-liners, inverted aphorisms, one-off nonsenses. As with Allen, on their own these sound like something out of Pop Philosophy I, but they accumulate into something more serious, and ontological, and because they’re not bound by narrative flow, hysterically Freudian. But you do have to grab at the language to get a footing. And bells ring as scenes end abruptly and you feel like Pavlov’s dog, stimulated though in this case not sure of your response.

As has been often commented, Foreman puts his audience in a new phenomenonological relationship with theatre. Once this was radically deconstructive (before the term had even gained currency), and it still can be, though 30 years of contemporary performance have made such gestures familiar. What is important is that Foreman’s is a body of work, 30 creations over as many years, unfolding as would a visual artist’s, a tightly conceived cosmos in which combinations of objects, language and sundry personae enter into new permutations. This is not simply deconstruction, you can’t only define a work of art by what it opposes or explains. It’s a unique way of regarding the world…and theatre. It stands on its own. It’s one man’s vision.

Strange then to see a local company, Kitchen Sink, announce that it was going to do a Foreman–My Head Was a Sledgehammer (1994). In contemporary performance the creator of the work is the one who performs it, embodies it. Not only that, but quite unlike the playscript, which can be realised in many ways, performance comprises multi-planed texts of which language might be just one component. A new interpretation of a playtext is always a possibility. But what do you do with the texts of performance–mimic the total effect? However, some American performance has a strong literary streak: Lee Bruer, Richard Foreman and others offer substantial texts that can be intrepreted in different ways from their Mabou Mines and Ontological-Hysterical Theatre originals, not that it’s likely, but…

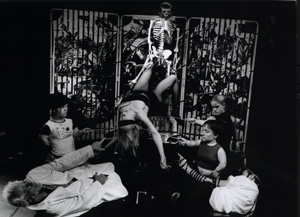

Kitchen Sink hit a happy balance–the production is Foreman-like, but no carbon copy. The set evokes a mad collector but has neither the space (Downstairs Belvoir St in its new format) nor the inclination to reproduce Foreman’s pictorial vision. Nor can the one-off ensemble reproduce the heightened physical and verbal poetry of the Foreman team. But they do more than a good job as the driven trio of Professor and Students, head-miked and sound-tracked, more animated than perhaps warranted in a small space, but physically dextrous and incredibly responsive to the (il)logic of the language, and to the abrupt gear changes of scene shifts. Helmut Bakaitas as the Professor is a melancholic seeker of truth, his rich resonating vocal timbre perfect for the god-like delivery of platitudes and his worrying at quandaries: “I make up rhymes, but they don’t rhyme,” “The unintended becomes true…I speak it…it becomes true.” Cartesian neatness and cause and effect count for little in this universe, especially when love enters the picture–the Professor’s collapse is a rivetting moment, a sudden psychological faultine opening up along the surface of abstractions. Melissa Madden Gray teetering on a single ballet shoe

excels physically and vocally, and Benjamin Winspear, swathed in phylacteries and stomping in workers boots exudes frightening power. They are the self-possesed Students, all raw energy and possibilities, the youth the Professor has lost, projections of desire and religious yearnings. Mind you, the riot of imagery and utterance means that it’s hard to put your finger on what you’ve just barely understood before Foreman’s world moves on.

Director and sound designer Max Lyandvert (who worked with Foreman, 1996-97), designer Gabriela Tylesova and the performers (including the 3 “gnomes”–Kiruna Stamell, Diana Cottrell, Amanda Shipley–the mysterious managers of the action), do a fine, engrossing Foreman. If only they’d do more but I’m sure that’s unlikely, their biographies suggest work as interpreters on many theatrical fronts, not the single, dedicated line of performance. As for the master, I recall Richard Murphet commenting in London, after we’d seen our first Foreman, words to the effect: “Isn’t it funny. We’ve finally seen the work of someone who’s influenced our work all these years and it’s great but it’s…too late. Like being in a museum.” Richard remembers then “thinking if not saying ‘The artefact is just as I imagined, perfectly preserved…but somehow not to be touched. The display case may have to be cracked open.'”

Kitchen Sink, My Head Was a Sledgehammer, by Richard Foreman, B Sharp season, Belvoir Downstairs Theatre, Sydney, Aug 9-Sept 2

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. web