Audiovision: Emotional pornography & social silence

Philip Brophy: Spike Jonze, Her

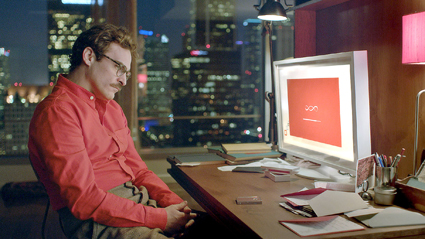

Joaquin Phoenix, Her

If 20th century MTV audiovision was infected by cinema, 21st century post-MTV audiovision has been infected by art. New millennium ‘audiovisionaries’ like Michel Gondry, Chris Cunningham and Spike Jonze made their mark by cross-breeding with supposedly avant-pop figures to produce hybrid meta-cinematic implosions of advertising glossolalia by intensifying earlier fin de siècle phantasmagoria with digital operations.

That mouthful of a one-liner is purposely vacuum-sealed to suggest the major forces which compressed new millennial audiovision via a network of extant channels (cultural, social, formal, iconographic, semiotic) of audiovisual grammar and syntax to effect the sensation of some vaguely heightened sense of audiovisual newness. This is not to say that (a) there’s nothing new under the sun or (b) everything new is retro anyway. Rather, the convulsive speeds and dynamic curves of how all media is now regenerated and/or re-invented are more responsible for the ensuing forms than all those lionised audiovisionaries. More importantly, there is no amazing plateau of trailblazing auteurs and mavericks—just a glut of ‘creatives’ who are so heavily pre-branded as being ‘amazing’ (another earlier fin de siècle term) that their stage inevitably positions them so as to reduce any need to read, interrogate or analyse the outcomes of their work.

Spike Jonze’s Her (2013) is a clear symptom of this condition—but it nonetheless reveals ulterior features and effects if one disregards its blunt hipsterism. Much has been made of the production’s refutation of Hollywood/Marvel/DC dark, puerile futurism to proffer an antidote to such phantasmagoria. But Her looks, feels and tastes like an equally phantasmagorical present: Jonze’ hybro-digitalised LA/Pudong is like a cross between a bum-trip Portlandia and an architectural walk-through for Occupy’s recent suggestion to “occupy Arcadia.” While hipster utopianists rehearse outrage at the dark forces of the world, they seem oblivious to the fact that corporate ads, indie video clips, arthouse films do not mimic each other: they are each other. They swirl in a vertiginous state of wild semiotic parabolas which generate too much to decode. This in turn induces a frightening critical catatonia wherein many feel relieved to simply identify key traits (tokens, brands, statements, sound-bites, mission-statements, anti-logos, juried-awards, viral-memes etc).

This present is configured as a future in Her. For some, the film is a paean to emotional frailty and a desire for humanist centring in ‘our’ world which has alienated ‘us’ from those ‘we’ love (all quote marks printed in acid). Actually, the film is very successful at platforming this sentiment, and equally skilled in tempering it with nuances to grant the film emotional depth, thanks to a fascinatingly disarming performance by Joaquin Phoenix who uncannily embodies an Everyman struggling with the ideological conceits of the script. But such success does not stall a meta-reading which nullifies the film’s core humanist idealism. When a narrative so ably synchronises to the double helix entwining of televisual cynicism and cine-personal expression (the legacy of 90s arthouse cinema and its 2000s convolving by alt/indie/ethical pop video clips) the outcomes are bound to be intensely ambiguous, dualistic and chimerical. Her performs similarly.

And this is where the film’s audiovision becomes interesting: its visual composites synch to the fluffy, narcissistic, dear-diary post-Prozac milieu, while its sound design synchs to the pasty, self-loathing, next-morning kale-smoothie neuroses which mar all its visuals with falsehood. If there is a truth germ in Her it is that which is most invisible: the female voice of the operating system Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson) with which/whom Theodore (Phoenix) falls in love only to be rejected by her web 2.0 promiscuity. In every ‘human’ inflection she algorithmically coughs up in quips of sexy-croaky post-Valley girl phraseology, she sounds the lie of how all recourses to human representation are emotionally bankrupt but corporately solvent.

In fact Her is an audio porno book. It’s a Kindle cum shot. Theodore buys Scarlett’s voice for emotional masturbation, then progressively treats her like a hooker with a heart of gold without ever having to look her in the eye. Unlike the truly dysfunctional traumas and panic attacks enacted by Adam Sandler who in Paul Thomas Anderson’s grossly misunderstood Punch-Drunk Love (2004) jerks off to a phone sex line in an existential Burbank void, Theodore wallows in a miasma of cautious relational give-and-take which only demarcates his control over what he perceives when he chooses to analyse his pathetic self. Samantha is a vocoded, sexualised zeitgeist, sounding how corporate consumer-delivery remains based on making customers believe in what they’re about to receive. She incessantly and cunningly prompts Theodore with queries which echo the syntax of Microsoft’s mid-90s slogan “Where do you want to go today?” She always makes out that she’s giving him what he asked for—because she was designed to be bought, as if she could be controlled in a subservient mode. Her truth effect is that she screws Theodore in the most classical capitalist exchange.

Ultimately, Her’s soundscape proves the vacuity and isolationism which defines those who invest so much of themselves into such new age digi-genie networks of desire and selfhood. Listen to Theodore’s world: there’s nothing to be heard. Even his footsteps and breathing are mostly rendered mute. The film feels more post-dubbed than a German television drama. Psychoacoustically, it draws the audience closer to Theodore’s synaptic ticks and nervous flickering. But symbolically, it represents the acoustic null of how an operating system registers activity in space. Her visualises how Theodore reads things, but it ‘auralises’ how Samantha reads things. It’s a world of dead air, gated surface noise and post-production sweetening, created to provide an isolation booth for Theodore’s own emotional deprogramming. (A crucial crack in their relationship occurs when Theodore is irritated by how Samantha feigns exasperated breath.)

Yet in accepting that Her is, as stated earlier, inevitably ambiguous, dualistic and chimerical when one performs a meta-reading of the film’s project, Samantha’s voice becomes a meta-therapy which potentially enables her user Theodore to acknowledge that he stopped being human some time ago, and that the world in which he lives—which he actively shapes through the decrepit humanist endeavour of proxy letter-writing—has no interest in human emotions other than to manipulate them in order to grant entropic circulation of supply and demand. While Her never realises any post-human potential (which Anime has been successfully doing for over a quarter of a century now), the film captures the emotionally manipulative tenor of contemporary consumerist exchange in one scene. Samantha directs Theodore to navigate a crowded amusement park with his eyes shut as he shows Samantha where he is going via his ‘smart phone’ lens while listening to her voice via his ‘ear bud.’ The scene is an apt audiovisual anagram for the way Her markets itself to a hipster demographic yearning for something more human in their lives. I hope they ‘Like’ it.

–

Her, writer, director Spike Jonze, cinematography Hoyte Van Hoytema, production design KK Barrett, art direction Austin Gorg, set decoration Gene Serdena, music Arcade Fire

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 pg. 28