Ephemerality capture and kin

Keith Gallasch: QUT Art Museum

Allora & Calzadilla, Stop, Repair, Prepare: Variations on Ode to Joy, No.1 2008, modified Bechstein, installation View: Gladstone Gallery, New York

David Regen © Allora & Calzadilla, courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

Allora & Calzadilla, Stop, Repair, Prepare: Variations on Ode to Joy, No.1 2008, modified Bechstein, installation View: Gladstone Gallery, New York

NO BREEZING THROUGH THIS SHOW. YOU’LL NEED HOURS, MAYBE DAYS. IN PERFORMANCE NOW, A COLLECTION OF SIGNIFICANT WORKS WILL BE SIMULTANEOUSLY EXHIBITED ON SCREEN IN THE MUSEUM. THEY COMPRISE VARIOUSLY BRISK, EPISODIC AND DURATIONAL CREATIONS—SERIOUS, WITTY AND PROVOCATIVE—BY PERFORMANCE ARTISTS, VISUAL ARTISTS WITH AN INCLINATION TO PERFORM (OR HAVE OTHERS DO IT FOR THEM) AND FILM, VIDEO, THEATRE AND DANCE MAKERS, EXPANDING OUR SENSE OF WHAT COMPRISES PERFORMANCE TODAY.

While some films and videos document significant performance art works, others are stand-alone exemplars of inventive interplay between performance and video art/filmmaking. Most have been made since 2000. The show is co-organized by Independent Curators International, New York, and Performa, the influential biennial of performance art organized by performance art scholar and curator RoseLee Goldberg. Goldberg, author of Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present (1979) is a former director of the Royal College of Art (RCA) Gallery in London, curator at The Kitchen in New York and teaches at New York University. Performance Now is the logical extension of her many years of staging exhibitions and symposia and encouraging extensive archiving. Above all, this widely travelled show is evidence of growing interest in performance art and in new kinds of art performance that overlap with a diversity of live art practices.

Performance Art itself made a comeback in the 2000s, with Marina Abramovic centrestage, training a new generation of artists and wielding commercial clout. A limited edition video of her 1977 work Imponderabilia, with partner Ulay, sold to galleries and private collectors for 180,000 euros a copy at the 2012 Art Basel. Gallerist Sean Kelly promotionally re-staged the work at the narrow entrance to his booth, requiring those entering to squeeze, as in the original, between two still, naked performers.

In Sydney in 2013 The Kaldor Project’s 13 Rooms (RT115, p5-7) excited the public imagination and angered others who felt performance art had been turned into a sideshow with live art entertainments and overly managed durational works. In the same year, Mike Parr in Daydream Island kept his body and its tortured durability centrestage but added a surprising theatricality (RT120, p5). Performance art is mutating—Parr was an early venturer in transmitting his work Malevich online in real time from Artspace where he was performing in 2002 (RT52, p28).

Just where the internet will take performance art has yet to be seen, but it will doubtless be partly judged in the same terms that screen documentation used to be: that it devalues the primacy of the body and the liveness of the performance by favouring the screen itself. Performance Now, with its mix of documentation and works that can only exist as film (like William Kentridge’s animations) will challenge doubters. Of course, as some performances become screenworks, they also become collaborative, with performers relying on the skills of others. The original, highly individualistic impulse of performance art—rejecting the commercialisation of art and the dominance of galleries by turning to the authenticity of the body—is still with us, but the forms it can take have been extended, as has its reach. Tino Sehgal is certainly keeping to the spirit of the pioneers—even as he rakes in the dollars (sales figures not disclosed)—accepting only verbal contracts for his works which are driven by spoken instructions and must not be documented, thus retaining immediacy and still highly-prized ephemerality.

Marina Abramovic performing Joseph Beuys, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965) performance; 7 Easy Pieces, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2005

Attilio Maranzano courtesy Marina Abramovic and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

Marina Abramovic performing Joseph Beuys, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965) performance; 7 Easy Pieces, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2005

At the centre of Performance Now, certainly in terms of viewing hours as well as influence, is Marina Abramovic, soon to visit Australia again. She appears in the documentation of her Guggenheim Museum seven-day, seven hours per day Seven Easy Pieces (2005) in which she “channelled” performance art greats in classic works: Bruce Nauman (Body Pressure, 1974), Vito Acconci (Seedbed, 1972), Valie Export (Action Pants: Genital Panic, 1969), Gina Pane (The Conditioning, 1973), and Joseph Beuys (How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, 1965). These are shown alongside Entering the Other Side (2005) and Lips of Thomas (1975) in which the ingredients are the artist naked, red wine and honey (to be consumed), flagellation (self-applied), cutting (a pentagram into the stomach) and an ice cross. These works are shown unedited, simultaneously and the screens arranged in a circle—an interesting way to deal with focusing and switching attention with onscreen durational works.

Among video works is the laidback, sitcom-ish (pay attention to the dialogue) activism of Stealing Beauty (2007) by Guy Ben-Ner whose fun critique of consumerism and the nuclear family features the artist, his wife and children illicitly inhabiting IKEA display rooms in various countries. Stealing Beauty resonates nicely with the family in Kevin Wilson’s very funny novel The Family Fang (Picador, 2011) in which children are trapped in their artist parents’ interventions. The Ben-Ner kids however seem fine, but you do wonder.

In Christian Jankowski’s Rooftop Routine (2007), citizens of New York’s Chinatown happily hula-hoop on rooftops—so can you with the hula-hoops provided in the gallery.

In darker territory, choreographer Jérôme Bel’s Véronique Doisneau (2009) features a corp de ballet Paris Opera ballerina who simply talks about her career and the torturous conditions in which she works. In Ryan Trecartin’s acclaimed video A Family Finds Entertainment (2004) “a black-toothed kid named Skippy (played by Trecartin) borrows money from his parents, is filmed by a documentary filmmaker, is hit by a car, then filmed again as he lies in the road…his soul seems to rise from his body when it hears the sounds of a rocking house party” (program note).

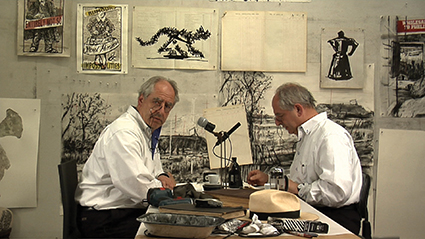

William Kentridge, Drawing Lesson 47 (Interview for New York Studio School) 2010, Single-channel video, colour, sound, 4 min., 48 sec.

Courtesy of the artist

William Kentridge, Drawing Lesson 47 (Interview for New York Studio School) 2010, Single-channel video, colour, sound, 4 min., 48 sec.

Elsewhere in Performance Now, William Kentridge stages an interview between his ‘good’ and ‘bad’ selves in Drawing Lesson 47 (Interview for New York Studio School) (2010) deploying his virtuosic animation skills in which the world constantly reconfigures. Another South African artist, Nandipha Mntambo, reflects darkly on colonial violence by playing a male Mozambiquean bullfighter preparing to fight in an abandoned Portuguese arena in the brief film Ukungenisa (2008).

These are just a few indicative examples of the range of art making involved in Performance Now, a show that demands pilgrimage from across Australia and all the durational immersion you can gladly muster.

Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Art Museum, Performance Now, 6 Dec 2014-1 March 2015, Brisbane

RealTime issue #124 Dec-Jan 2014 pg. 22-23