epiphanies and play

john bailey: melbourne international arts festival

Opening Night, Toneelgroep Amsterdam

photo Jan Versweyveld

Opening Night, Toneelgroep Amsterdam

FROM A DISTANCE, IT WOULD APPEAR THAT BRETT SHEEHY’S SECOND MELBOURNE FESTIVAL WAS THE MOST CONTROVERSIAL IN YEARS—NOT FOR WHAT IT OFFERED, BUT FOR WHAT IT LACKED. CRITICISING AN ABSENCE IS ALWAYS A SHAKY STARTING POINT, BUT FOR ME THE FREQUENT KEENING (FOR A NO-HOLDS-BARRED-EPIC; FOR A CENTRAL CONVERSATION HUB; FOR A CITY-CHANGING EVENT) DREW ATTENTION AWAY FROM THE FACT THAT WHAT WAS PRESENTED WAS OFTEN EXCITING, REWARDING OR SURPRISINGLY ENGAGED WITH ITS ENVIRONMENT. THE HITS OUTWEIGHED THE MISSES, AND EVEN THEN THE TRAIN-WRECKS WERE MOSTLY HEAD-TURNERS.

toneelgroep amsterdam, opening night

Take Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s Opening Night, an outrageously ambitious and strikingly realised merging of realist drama, filmic de- and re-construction and theatrical conjuring. Taking its cues from the screenplay of the 1977 Cassavetes film (RT99, p15), it presented the behind-the-scenes preparation for the premiere of a new play in which interpersonal tensions and past grievances threaten to derail proceedings. The imminent meltdown of the leading performer acted as an emotional 18-wheeler bearing down on the edifice of appearances erected to conceal these fragile relationships.

Simultaneously, a set of real time cameras and projections reproduced the live performances as a filmic spectacle beamed across the space and on downstage monitors. The result was both a hyperreal, immediate play and a fragmented panoply of artificial surfaces, each of which could not be fully separated from the other. The power of the screen image to seduce our gaze constantly asserted itself, even if that image was just the second-order rendering of the fleshy, three-dimensional bodies being flung around the stage before us. Cinema’s epistemological status as a negation—as always referring to an elsewhere, an else-when—also produced a rich confusion, compounded when the projected image seemed to lag behind the real events, or freeze. Technical hitch or cunning ploy? What does it matter?

Hiroaki Umeda, Haptic

photo Alex (sic)

Hiroaki Umeda, Haptic

hiroaki umeda, adapting for distortion, haptic

An astonishing technological wizardry also animates Japanese choreographer/dancer Hiroaki Umeda’s paired billing of Adapting for Distortion and Haptic. In both, light is central to any meaning generated by the work—the body subsumed by the post-human abstraction of light. Indeed, Umeda seems to epitomise Donna Haraway’s conception of the ideal cyborg as a machine made of sunshine. Identity and the individual are stripped by the excoriating divinity of luminescence, but this works to radically different effect in the two pieces.

Adapting for Distortion is a monstrously visceral encounter with the binary order of 21st century technology. Fast-shifting grids of light, expanding and contracting potentially infinite horizons destabilise any sense of depth, in a case of Cartesian perspective taken beyond the capacity of the mind to comprehend. Approaching the sublime in its most classically terrifying of definitions, it was seizure-inducing stuff that made for anything but a pleasant experience. Hard to argue with its effectiveness, however, and the work, though brief, acted as a potent reminder of the unseverable connections between our physical forms and the perceptual capacities that orient them in space and time.

Haptic presented a marked contrast in tone. Here the dancer was a liquid shadow against warm, shifting waves of coloured light; a half-visible organism skittering across the surface of a radiant lake of unfathomable depth. Where Adapting to Distortion’s alien landscape was one of cold dislocation, Haptic produced a pre-Oedipal plenitude, the return of the individual into a fullness of being where world and self no longer suffered rupture.

It seems paradoxical that within these two works Umeda still managed to carve out a distinctive style of dance. Though he may now claim to be more visual artist than choreographer, his performance still drew on techniques of classical dance and hip-hop—body rolls that defied the limits of the skeletal, foot-slides of eye-blinking dexterity.

Tomorrow, In A Year, Hotel Pro Forma

photo Claudi Thyrrestrup

Tomorrow, In A Year, Hotel Pro Forma

hotel pro forma, tomorrow, in a year

Despite this particular style, it’s not easy to determine Umeda’s contributions to Hotel Pro Forma’s electro/dance opera Tomorrow, In A Year. He is billed as “choreographic consultant” but none of his signatures are legible—instead, the elements of dance here appear so naively rendered as to make me wonder if this is deliberately the case.

Tomorrow, In A Year is one of those rare encounters where I wonder too if some elaborate prank is being pulled. It’s self-consciously obscurantist, visually drab and gestures towards complexity and exquisite chaos without actually engendering either. It takes its inspiration from the life and writings of Charles Darwin, but its collision of elements—divergent modes of dance, vocal styles, visual effects and the very forms of opera, electronica and postmodern theatre—result less in a new species of performance evolving beyond its ancestors than a lumbering Frankenstein’s monster in natty duds. There’s no natural law which states that the combination of random genes will produce a hybrid able to survive, any more than a random combination of words will result in a comprehensible sentence. And while the libretto may have drawn heavily on Darwin’s own words, phrases such as “Scissor-beak lower mandible flat elastic/it’s an ivory paper-cutter” make me focus less on the evolutionary arc of the avian than the increasing furrow of my brow.

michael clark company, come, been

& gone

If Tomorrow, In A Year falters under the weight of its own ambitions, Michael Clark Company’s come, been and gone is crushed beneath the onus of its own history. Paying tribute to several decades of work by the renowned British choreographer, its supposedly groundbreaking rebellion appears tired and shorn of context today. Set to a series of songs by artists such as David Bowie and Lou Reed, at its worst it presents an embarrassing literalism: The Velvet Underground’s “Heroin,” for instance, produces a dancer in a flesh-coloured bodysuit studded with foam needles writhing around in someone’s half-baked notion of a drug nightmare. For Bowie’s “Heroes,” the audience is even provided a large-scale projected video of the track’s video clip—it’s a hard task for rather uninspired dancers to compete with such an iconic figure, especially when the image isn’t deployed with the kind of understanding of its fascination suggested in Opening Night.

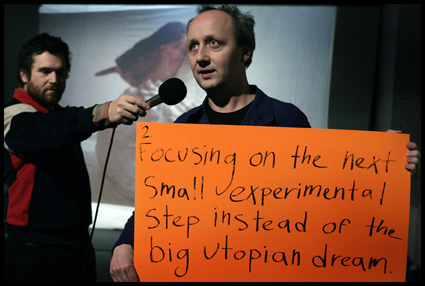

An Anthology of Optimism, Jacob Wren, Pieter De Buysser

photo Phile Deprez

An Anthology of Optimism, Jacob Wren, Pieter De Buysser

wren & de buysser, an anthology of optimism

There is inspiration to be found in Jacob Wren and Pieter De Buysser’s An Anthology of Optimism, but it’s of a coy and delicate sort. The pair—both writers, one a performance artist and the other a sort of contrarian humorist and philosopher—present a lo-fi dialogue exploring a notion of “critical optimism.” It’s a somewhat Socratic exchange with a clear argument and obvious structure. Wren is established as a sceptic, suspicious of the potential for optimism to bear any efficacy in a contemporary climate as troubled as ours; De Buysser takes the case for an optimism which admits of the world’s troubles without succumbing to defeat. Eventually they find some agreement: a cautious kind of positivity that promotes small steps in the face of big problems. It’s not radical thinking, but it makes its point both succinctly and without excessive guile.

The conceit of the production is delivered in a style that often threatens to tip over into a terrible tweeness. A retro slide projector, hand-written signs and a manually operated sound system nod to the mode of conspicuously no-frills, DIY theatre, but there’s a strained casualness to the performances that seems the result of much effort not to become mannered or artificial. Perhaps that would have created a tone of seriousness, undermining the inherently didactic nature of the work; these days, self-conscious irony is a more acceptable way of putting forward very political points.

But this is exactly the sort of work that, for me, fleshes out an international festival. It’s not a grand showcase of spectacular talent—as works like come, been and gone and Tomorrow, In A Year indicate, such productions too often make for monumental disappointment. Opening Night proved the exception, but on a smaller scale this year’s festival was marked by a great number of successes that add up to something more than two weeks of art with a single defining moment. I don’t know that festivals of this sort need such a defining moment. Rather than stamping in our minds an image of one event over all others, this year made for a plurality of miniature epiphanies and quiet fades, even blurring into the surrounding non-festival productions. That’s worth our attention, at least.

2010 Melbourne International Arts Festival: Toneelgroep Amsterdam, Opening Night, after John Cassavetes’s Opening Night, director Ivo van Hove, design, lighting Jan Versweyveld, video design Marc Meulemans, Playhouse, Victorian Arts Centre, Oct 20-23; Adapting for Distortion, Haptic, choreographer, dancer Hiroaki Umeda, sound S20, images S20, Bertrand Baudry, lighting S20, Hervé Villechenoux, Merlyn Theatre, Malthouse, Oct 14-17; Hotel Pro Forma, Tomorrow, In A Year, directors Ralf Richardt Strobech, Kirsten Dehlholm, music The Knife, design Ralf Richardt Strobech, State Theatre, Arts Centre, Oct 20-23; Michael Clark Company, come, been and gone, choreographer Michael Clark, lighting design by Charles Atlas, costumes Stevie Stewart, State Theatre, the Arts Centre, Oct 8-10; Pieter De Buysser and Jacob Wren/CAMPO, An Anthology of Optimism, Fairfax Theatre, the Arts Centre, Oct 20-23

RealTime issue #100 Dec-Jan 2010 pg. 8