Every available space

Virginia Baxter

Gravicells obara

MAAP's Artists Talks convene among the ruins of the opening night Zero Gravity party at which members of Singapore's Artists' Village and the web-based tsunamii.net took over Singapore Art Museum's Glass Hall, creating a playfully chaotic celebration of video, sound and performance art with a live broadband link to the Creative Industries Precinct at Brisbane's QUT. The following day, chair of the symposium's first session, Julianne Pierce smiled amid the debris, suggesting that in a city which prides itself on order, one of the functions of a festival like MAAP might be to offer some room for a little mess.

Alexie Glass from the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) described the video exhibition she co-curated, I thought I knew but I was wrong (Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts), as manifesting “uncertainty, permeability, leakage and breakdown in communication.” This project sprang from Asialink's Sarah Tutton's residency at ACMI. As the exhibition tours for 21 weeks around Asia, the curators will collect works from Asian artists for a future reciprocal exhibition in Australia. To install the exhibition, we heard, required the Academy to adapt one of its white spaces to black. Pleased with the result, they're thinking of retaining it. Spaces virtual or real become a significant trend

Like the rest of Australia, most artists at MAAP listen with envy to descriptions of the creative spaces opened up by ACMI. On the other hand, Gridthiya Gaweewong, the dynamic curator of the -+-(negative plus negative) exhibition who these days describes herself as “loosely based in Bangkok” with a homeless gallery, talks up the value of small spaces. At MAAP we're surrounded by “mobilised” artists. In 1996 Gridthiya “accidentally” co-founded a new media art movement when, with a collection of conceptual thinkers and new media artists she set up a small non-profit space with interdisciplinarity as the connecting concept. Many of the participants had been trained outside Thailand in the UK or US and together they established a gallery in an apartment which later moved to a house. The group began to enter the broader new media arena initially via the 2004 Switch Media Art Festival in Chiangmai. Though a number of universities in the region have since opened new media departments, the movement is still small and mobile in Thailand and the place of new media art with its demands for technical support and infrastructure negotiable. In the gallery notes for the negative + negative exhibition, one artist wondered, “if there is no such thing as media art here, do we need to create it?”

For New York-based Zhang Ga, the space of new media art lies in ephemeral domains as well as tangible spaces. His large scale public art work, The Peoples 'Project, sponsored by MAAP and Reuters among others, consists of a number of small photo booths set up in cities including Rotterdam, New York, Linz, Brisbane and now Singapore with links to large projection screens in major venues including the giant screen in Times Square and the biggest video wall in Shanghai. You enter the booth, flick a switch and in an instant you're not quite famous, but visible at least, however fleetingly, across 7000 square feet of digital display around the world. Zhang Ga defines this work as “a dialogue with portraiture” which, in the digital space, he sees as being about scale and speed. This is a project for the “peoples” of the world (not “people”) and aims to satisfy their “urgency for expression” in response to the “overwhelming presence of technology.”

There are now over 3000 people/s on the database and it's hungry for more, as are new media events the world over, presumably for projects to fill their “popular new media art” slot. Zhang Ga, who's a professor at the MFA Design and Technology Program at Parsons School of Design and Technology in New York, reports that space for new media art is closing down in the US with funding reductions and galleries cutting back their commitment. Hence his belief in new possibilities offered by projects which allow ordinary citizens to “subtly insinuate” themselves into the landscape. Zhang Ga is one of a number of artists at MAAP who see themselves as ‘conduits’, defining the parameters of these new spaces in which “the people” create the work. Participants in The Peoples' Project who enter the booths are informed about the trajectory of the photograph but the extent to which they knowingly collaborate in an artwork is less certain. The potential for this project to go beyond the “Look at me!” and open up an uncensored space for pockets of creativity seems more interesting than its loftier aim of “bringing peoples together.” Already in what we see of the public's response, there are signs of messy human interaction in the range of expressiveness and camera angle. And let's face it, at a time when artists are eagerly whipping up 90-second art films for mobile motion capture platforms, 15 seconds of screen time in a major venue is prime creative real estate. I see gradually unfolding manifestos, bodies of work emerging. The sky’s the limit.

Fatima Lasay is among the impressive representation of female artists, curators and organisers at MAAP who are taking on the new media territory and transforming it with their aesthetic and political concerns. Hailing from Manila but, like many artsworkers here, moving across continents, Lasay argues for loose and localised concepts of technology. For her the issue is empowerment and for artists in places like Myanmar this means using whatever medium is at your disposal, technological or otherwise (see Keith Gallasch, “The body between: Fatima Lasay, an interview/review”).

Shu-Lea Cheang is another mobilised digital artist, currently based in Paris. For her, art is all about transgression and public space. She’s interested in “open systems, open culture” and in building collaborative platforms in preferably cross-cultural formats. Initially inspired by those images from Asia which shot around the world of pirated CDs being burned or run over by steamrollers, Shu-Lea created The Kingdom of Piracy (kop.fact.co.uk), a space for a variety of actions including the web interface work on exhibit at MAAP called Burn in which visitors create their own take-home pirated CD. This work was created as part of a residency at FACT Media Centre in Liverpool, UK. For Shu-Lea, a new media pioneer who’s been working the terrain for around 10 years now, the challenge lies in creating structures, new collaborative platforms for people to express their ideas. “What remains of bandwidth must be used as public space,” she declares. In richair.waag.org teams of young women on rollerblades access wireless signals via signal boosters in lunchboxes. In tramjam.net, music is synchronised in a multi-track, multi-driver mix hub designed to intersect with the intricate train timetable network. An Australian in the audience asked what would happen if the trains were late. Surprised at the question, Shu-Lea answered that, in Europe, trains are never late!

Xing Danwen (China) is one of the artists involved in MAAP’s online residency program. For the GRAVITY exhibition, she is displaying in a series of projections, her photographs of the e-trash of Europe and especially the US which is shipped in to China and recycled by local workers (see cover RT#63). Born in the 1960s Danwen invokes dreams of modernity compared to current realities. In another recent piece, Urban Fiction, she works with architectural models of high-rise precincts, inserting within them photographs of human characters (played by herself). In an apartment space, a small cardboard figure lies prone in a pool of red ink, the perpetrator of the “crime” standing over her. The space around the couple is mute, the disaster barely discernible amidst the order of the architecture. Xin Danwen is interested in public space and the private life within it, the fixity of an architectural model and small fictions that challenge it. The idea began when she left her home in China to study in New York and sensed sharply the difference between the 2 places. She challenges the notion that these days “everywhere can be anywhere.” In an earlier work, Sleepwalking , exhibited at the Yokohama Triennale in 2001, she recorded sounds in China and played them as part of a video installation, splitting the images between simple projection onto a wall and simultaneously into a glass trunk full of water.

Currently working in Brisbane, Agnes Hegedüs is also a child of the 60s. Born in Hungary, her background is in the fine arts but she now defines the aesthetic input into her work as “marginal”, an act of creative erasure that unsettles me for some reason. Observing the ways technology has infiltrated our lives, Hegedüs became interested in identifying what it was actually good for and decided that the answer lay in creating opportunities for interactivity –”Art is for people”, she says. As a consequence, having worked her way through complex sensor-based CD-ROMs and DVD-ROMs, she now prefers to use technology for communication with other people, or setting up interfaces with which one person can engage. Watching the process and seeing how people use it drives her next idea. In her work, Memory Theatre (memory.ci.qut.edu.au), visitors are asked to contribute an object which links to a personal memory. It reminded me of Sophie Calle's The Birthday Ceremony in which the artist displayed her birthday gifts in museum cases as tokens of affection. Agnes Hegedüs, however, has moved beyond the personal sphere, photographing and scanning other people's memory objects (artfully, it must be said) and collates them into a taxonomy of objects and ways in which people build identity around them.

Yukiko Shikata (Japan) looks beyond the horizon for more ephemeral possibilities for the internet and new media art projects in public space. A woman who wears at least 3 hats, she has facilitated and collaborated on many installations and accessible artworks that open up new spaces for interactivity. She spoke about the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and New Media (www.ycam.jp), an organisation with a strong investment in new media space in a city likewise committed. In Yamaguchi in 2003 Shikata curated Rafael Lozano-hemmer's Amodal Suspension in which missives from mobile phones were conveyed via searchlight into the sky creating “accidental encounters” and offering “new ways to imagine new people.” In an event in Tokyo, Garden of the Sinewave Orchestra, participants hovered with laptops at communing distance from plants picking up sine waves generated by sensors among the foliage.

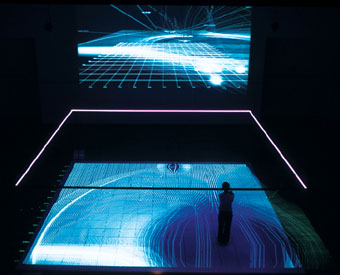

Lastly, Shikata showed us documentation of a sublime work entitled Gravicells by Seiko Mikami and Sota Ichikawa. It's an installation in which “realtime movements by participants generate and affect GPS, directional sound, LED light and projection images of geometrical data” (www.G–R.com). As visitors move across the map, self and space merge as the regular pattern of lines curves around them. It reminded me of some of the effects of some of the best work at MAAP–Kim Kichul's elegant sculptural experiments in making sound visible, Ji-Hoon Byun's falling light wall, Duk-eum, Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries' unfolding beat poem in signage, All fall down, and Marcus Lyall's liquid flight, Slow Service. In these works, we are invited into the artist's space to share an imagined world that exists for a time as an open house and if we're lucky we'll have the experience Ji-Hoon Byun has designed with us in mind:

When they arrive at the end

time is so accelerated

that they could not feel their vanishing.

The vanishing is (a) sad but beautiful one.

Here is something invisible

in this short fall.

Symposium: GRAVITY, The Glass Hall, Singapore Art Museum, MAAP in Singapore, Oct 30

RealTime issue #64 Dec-Jan 2004 pg.