Facing the evasion of the bitterest truth

Dan Edwards: Interview, Joshua Oppenheimer, The Act Of Killing

The Act of Killing

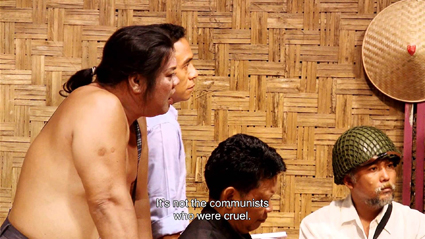

A line of dancing girls sashays from the mouth of a giant fish, the scene shot in such lurid tropical colours it appears poised on the edge of a nightmare. Welcome to the make-believe world of Indonesia’s death squads, built on the corpses of a million of their compatriots. Joshua Oppenheimer’s extraordinary new film The Act of Killing—“a documentary of the imagination”—renders this imaginary world on screen, as the killers who ushered in Indonesia’s “New Order” in 1965 enact their perspective on one of the largest massacres in history.

“I felt like I’d walked into Germany 40 years after the Holocaust only to find the Nazis still in power,” says Oppenheimer of his first encounter with one of the killers. “He immediately launched into horrific stories of murder, because killing was the basis of his career and the most important thing he had done in his life. And he told these stories in front of his granddaughter and wife. I thought in that moment, if this man’s not crazy, if this is how the killers really talk, then I knew I would have to give this situation whatever it took of my life to try and understand it.”

Oppenheimer’s commitment took him on a five-year journey that saw him interview more than 40 ageing death squad members. Their killings in 1965 were the culmination of simmering tensions between Indonesia’s Communist Party, the military and various religious groups in the first decade and a half of the young nation’s existence. Indonesia’s inaugural leader, President Sukarno, had attempted to balance these competing forces within a pluralistic political sphere, united by a commitment to Indonesia’s newly won independence and an anti-colonialist stance towards the rest of the region.

Sukarno’s balancing act came undone with the murder of six generals on 1 October 1965 in an abortive coup. Who instigated the coup remains unclear even today, but what’s not in doubt is that Suharto, one of the surviving generals, seized control of the situation and used the unrest as an excuse to launch a massive purge of communists, unionists, ethnic Chinese and anyone with leftist sympathies. When the dust settled, up to a million were dead, Sukarno had been toppled, Suharto was president, and Indonesia had unambiguously sided with the United States in the Cold War.

Oppenheimer’s interviews with various killers of the period led him to Anwar Congo, a petty criminal with a kindly face and a penchant for American gangster flicks. Anwar claims he personally tortured, bludgeoned and strangled around 1,000 people in the mid-1960s. “I lingered on Anwar because his pain was close to the surface, and offered insight into the true nature of the boasting about the killings—namely that it was defensive, it was a desperate effort to convince themselves that what they had done was right, and to intimidate the rest of society into accepting that story,” says the director.

The Act of Killing

As Oppenheimer’s comment implies, The Act of Killing is as much about today’s Indonesia as the events of 40 years ago. For although we are told that Indonesia is now a democracy, Oppenheimer’s film clearly shows that the political terror, graft and gangsterism of Suharto’s “New Order” are alive and well. Throughout the film, we see interviews with present-day politicians in which they freely discuss their illegal moneymaking activities and reliance on the killers of 1965 to maintain their power. Throughout it all we constantly return to the over-lit interiors of Indonesia’s shopping malls, where the same elite figures indulge in the consumer dreams of the global capitalist system to which Suharto delivered their nation.

It was the intimate link between the terror of 1965, the contemporary political order and the lingering fears of Indonesian workers that led Oppenheimer to make The Act of Killing. “I first went there in 2001 to make a film about palm oil plantation workers,” he recalls. “The women were spraying a herbicide that was dissolving their livers. They really needed a union, but were afraid to organise because their parents and grandparents had been in a union until 1965, when they were accused of being communist sympathisers and dispatched by the army to civilian death squads.”

When his initial efforts to interview survivors of the 60s massacre were forestalled by the police and military, Oppenheimer decided to focus instead on the perpetrators. “Show me what you’ve done, in whatever way you wish” Oppenheimer told Anwar and his associates. “I’ll film the process, I’ll film your re-enactments, and we’ll combine these things to create a new form of documentary.”

Enthusiastically responding to this request, we see Anwar initially create scenes with an almost light-hearted feel, as he happily recounts the role he played in the purge. But beneath his bravado Anwar is clearly troubled, and when he tries to render the nightmares that keep him awake at night on film, The Act of Killing takes a turn that is at once laughably absurd and utterly horrific. By the time Anwar starts dissecting a teddy bear with a penknife to demonstrate what he did to the babies of communist suspects, we have descended into a very dark place indeed.

“It turned into a journey that was much bigger than genocide,” says Oppenheimer of the re-creation process. “It became a journey about how we as human beings make sense of our actions. How we understand ourselves.” He describes Anwar’s re-enactments as the killer’s attempt to “build up a kind of cinematic scar tissue,” to tame the unspeakable horror of what he did to his countrymen. And yet there is no escaping the agony Anwar inflicted, no matter what stories he uses to justify his actions.

In some of the film’s most disturbing sequences, Anwar’s fantasy world starts to unravel as he agrees to play a victim in one of his re-creations. Later, after watching the taped scenes, Anwar tells Oppenheimer that he now understands how his victims really felt. The director’s simple deconstruction of this claim—“but you were only acting, they were really dying”—leaves the killer standing naked, staring into Oppenheimer’s lens and the abyss of his own actions. For the first time, there are no stories left to hide behind.

For all the awfulness of these scenes, it’s The Act of Killing’s stripping bare of the act of history writing itself that remains the film’s most disturbing aspect. The purge of Indonesian communists has never been a secret—indeed, the manner in which these events have been framed has defined the country since 1965. The leftist political ‘other,’ Indonesia’s elites tell themselves, was a divisive force that had to be eliminated to guarantee Indonesia’s future prosperity and peaceful entry into the world economic system. It’s also this story that binds Indonesia’s elites to us in the West. For just as they have benefited from Indonesia’s prosperity, we have benefited from the submission of their workers.

Oppenheimer alludes to this point when I ask him if Herman, one of Anwar’s younger friends who acts in many of the re-created scenes, realised the extent of the slaughter upon which his society is based. The director replies, “Oh I think he realised, but he didn’t want to think about it. In the same way I realise that the shirt I’m now wearing was made in Bangladesh, and that the people who made it may now be buried under piles of rubble. Thanks to that, I can buy this shirt for six dollars. Like all of us, Herman uses fantasy and entertainment to withdraw from reality.”

After a loaded pause Oppenheimer adds, “That’s what this film is really about—how we all tell stories to escape from our most bitter and indigestible truths.”

–

The Act of Killing, director Joshua Oppenheimer, producer Signe Byrge Sørensen, Norway, Denmark, United Kingdom, 2012, distributed in Australia by Madman.

RealTime issue #117 Oct-Nov 2013 pg. 12