Fassbinder, degrees of proximity

German Film Fest: Annekatrin Hendel, Fassbinder

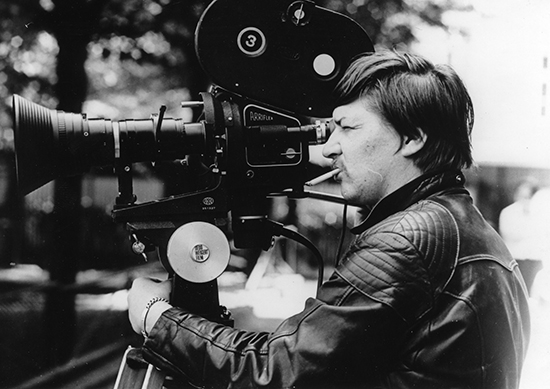

Rainer Werner Fassbinder on the set of Berlin Alexanderplatz, 1980

“I had to lead the life I led to be able to make my films.” Fassbinder in The Wizard of Babylon (dir Dieter Schidor, 1982)

The day after the filming of Schidor’s documentary was completed, Rainer Werner Fassbinder died, aged 37. A compulsive creator, with inordinate talent he had made 42 feature films, Berlin Alexanderplatz as a television series and written 26 plays.

The number of works is astonishing but more important is their scope. Has there ever been another film director who has so closely probed a national psyche and its history, from the late 19th century to the challenges of the 70s—the confluence of Baader-Meinhof and state terrorism, homosexuality and, in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), anti-immigrant racism. Fear Eats the Soul will show on the same night as Annekatrin Hendel’s documentary, Fassbinder, in Melbourne and Sydney, amid a strong festival line-up.

“Does it tell you more about the work—which is his legacy—or the man?” These words appear early in Hendel’s feature-length biography. They’re in white subtitles against a white background; I don’t know whose words they are, if quoted or the filmmaker’s. Even so, they invite judgment. Fassbinder is about the man, his relationships and their role in his compulsive output. The film assumes his genius; it’s not an appreciation of his craft. What it tells you about his work is that it was inextricably tied to his life, not how he made the translation of life into film or what shaped his filmmaking virtuosity. These are for other documentaries.

Hendel’s film draws principally on the personal reflections of those who worked closely with Fassbinder. Degrees of proximity—and sometimes brutal separation—in Fassbinder’s relationships with his collaborators are key to his creativity and the film’s power. Actor Harry Baer recalls joining the Action Theater (which became the Anti-Theater) and gradually realising that Fassbinder was the emergent leader, not the director Peer Raben (later, composer for most of Fassbinder’s films). Actor Hanna Schygulla recalls, “I noticed this boy, both touching and intimidating, both vulnerable and predatory, rapacious.” In due course she was seduced by “the ecstasy of acting.” Another key Fassbinder performer, Irm Herrmann, says that drugs and alcohol were not part of the younger artist’s life, just the compulsion to make; “I was totally under his spell.” She lived with him and then others, forming a collective, from which some actors kept a safe distance: “We would have killed each other.”

Hendel initially focuses on the making of Fassbinder’s first film, the noirish/Godardian Love is Colder than Death (1969) which despite being booed at its premiere won a German Film Festival Award in 1970. Volker Schlondorf, who was making Baal (1970; not distributed) cast Fassbinder as the poet. Fassbinder insisted not only that the director find roles for his ensemble and crew but that they all see the daily rushes and cuts. Shocked to find that his pay had been taxed, he demanded gross payments, “which is how he funded his next three to four films.” A TV producer describes Fassbinder presenting “as a sullen, temperamental rock star with a certain tangible aggression.” But in a long meeting, in which he smoked 20 cigarettes and consumed half a bottle of whisky, he negotiated the support he needed, resulting in “a frenzy of production, more and more focused on him.” Film titles flicker by in confirmation. At this stage Fassbinder, uncomfortable with large crews, was working with performers who took on, says Baer, two to three production roles each, resulting in “quick and efficient” filmmaking.

Fear Eats the Soul

Other aspects of working closely together were less agreeable. A principle Fassbinder performer, Margit Carstensen, says waiting to see who would be cast in the next film “was like a competition. Actors were afraid of him.” Stories of the director’s cruelties are chilling, including his casting aside male actors he had been in love with (and with appalling consequences), propelling Baer into his first gay sexual encounter (Fassbinder laughing as he watched), and his pushing Schygulla into on-screen nakedness beyond her comfort zone (she quit at one point).

The one film that gets extended attention is The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972), Carstensen revealing that, at the time, she hadn’t realised that the film “was an analysis of Rainer’s love life. He was Petra.” Hendel brings it home, rather cutely, in one of her film’s recurrent animations of imagined storyboard drawings, by having the two actresses in a key scene transform into Fassbinder and his married lover.

The challenges of acting for Fassbinder were clearly considerable. Herrmann was constantly belittled with the director “divulging intimate details” of her life before cast and crew. On the other hand, Fassbinder relied heavily on his ensemble (even as it lessened when he “brought in outside actors and stars,” like Dirk Bogarde in Despair; 1977). In one of a number of filmed interviews, Fassbinder says that he was “trying to develop a form of acting together with the actor, and it involves a development from one film to the next as long as [the director] is inspired by them and they by him.” This “development” was crucial to his output. As one actor puts it, “It was like a machine, road construction advancing slowly but surely.” As one film was being shot, the next was in pre-production under actor Kurt Raab.

A few other films receive close attention; The Marriage of Maria von Braun, for its trenchant account of post-World War II transformation of Germany—“as if nothing had happened,” says Schygulla. Another is Germany in Autumn (1977), an omnibus film with Fassbinder’s contribution widely regarded as the best. Thirteen directors try to make sense of the kidnapping and murder of a German industrialist, kidnapped and murdered by terrorists and the alleged suicides in prison of three members of Baader-Meinhof. Fassbinder sits naked on the floor, speaking on the phone, snorts coke and then argues over a meal with his (actual) mother, Lilo Tempeit, who appeared in a number of his films. Volker Schlondorf says that his fellow directors were mostly shocked by Fassbinder’s approach. As Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times, “It’s typically, intentionally disorienting in the Fassbinder way, photographed and acted with such intense self-absorption that it has the effect of transforming narcissism into a higher form of political commitment.” That narrowing of the apparent gap between the personal and the political was not only a marker of the 60s and 70s but especially of Fassbinder’s potent form of filmmaking,

Fassbinder’s decline, his friends report, was evident; “it was too late,” says Schygulla, who had presented him a farewell bunch of roses at their last meeting. His girlfriend, an editor on his late films, recalls his love for her, his desire for a child, his enduring love of men and a desire to escape the production machine.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Hanna Schygulla

Fassbinder is an engrossing biography. The director’s many collaborators are given ample time to be eloquently critical yet grateful and loyal. Schygulla is a strong presence, working at her painting as she speaks wisely with her characteristic, measured lilt. Fassbinder himself appears on TV monitors in the studio that frames the film, quietly authoritative save for one moment of distress after his play Garbage, The City and Death, had been refused production in Frankfurt (where he had become artistic director of a major theatre company, a short-lived venture) because of the play’s alleged anti-semitism. In the interview excerpt, Fassbinder expresses concern that someone with his record could be so accused. A 1985 production, three years after his death, was stopped after Jewish citizens occupied the stage and later attempts to mount it were challenged.

Annekatrin Hendel’s film gives us the life that led to the films: the rapid turnover of favourites, relationships and productions, complicated sexual relations and, regardless of the completion of so many works of art, profoundly unresolved desires. It left me a little depressed, if buoyed by those collaborators who survived Fassbinder’s clearly monstrous regime, but grateful for the information and rare footage of an artist I’ve long admired. But I’ll soon have to put some distance between the documentary and the Fassbinder films—in order to engage with the art, not the life, however inextricably they are entwined.

See a trailer for Fassbinder here:

Visit the German Film Fest website for screening sessions.

In Melbourne, an exhibition of film posters and homages, Fassbinder 1945-82, runs until 15 December.

RealTime issue #135 Oct-Nov 2016