Film as essay, performance as film

Keith Gallasch, Performance Now; Hito Steyerl

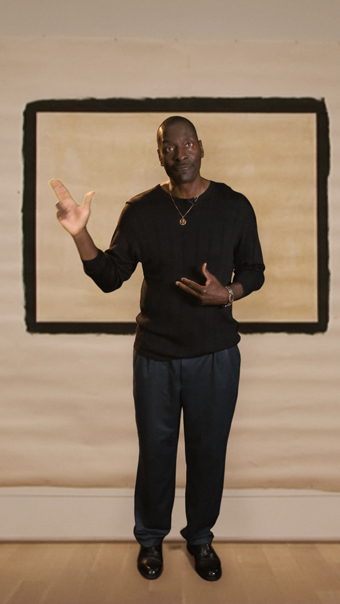

Guards (2012), Single channel HD video, 00.20.11.

© Hito Steyerl, courtesy Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam.

Guards (2012), Single channel HD video, 00.20.11.

I recently travelled to Brisbane to look at screens: the Too Much World exhibition of the film essays by Hito Steyerl at IMA and the RoseLee Goldberg curated videos of international performance works at the QUT Art Museum. These shows are well-staged, spaciously ample and low on sound bleed and there’s occasional seating, allowing sometimes long works to be comfortably experienced. QUT Art Museum (with ICI and Performa) and IMA (with partners Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Netherlands and the Goethe-Institut Australia) are to be congratulated for staging these significant exhibitions.

I enjoyed both immensely. However, there were not a few moments when I wondered why I wasn’t in a theatrette or at home with the DVD player instead of wandering about waiting for the starting points of long videos or when I might gain access to the headphones or how much of the seven seven-hour Marina Abramovic performances I would be able to take in. The validity of showing these kinds of works as if pictures hung on walls becomes questionable as durations accumulate.

Hito Steyerl, Too Much World

In Sight & Sound, filmmaker Kevin B Lee describes the film essay as a form that “critically explores cinema through the medium itself,” in an age when almost anyone, “with or without a camera,” can do so given the enormous availability of images and technical resources (“Video essay: The essay film—some thoughts of discontent,” 8 Aug, 2014). Lee asks, “Does this herald an exciting new era for media literacy, or is it just an insidious new form of media consumption?” It’s a question inherent in the works of Hito Steyerl.

Film essays can look like documentaries and will deal in facts, but they are principally and unashamedly subjective, often poetic in form and playful with film language. One of the most acclaimed contemporary film essayists is Berlin-based Steyerl, who complains that while galleries will pay to show her work they will not fund her films, forcing her more and more into cheaper methods of production and having to learn digital skills. This is evident in 2014’s Liquidity Inc, a wild 30-minute ride through interview (a stockbroker turned cage-fighter), raw performance, animation, appropriation and vision-mixing in an assault on the schizophrenic condition that is Neo-liberalism. Roles, images, titles and images of weather (Steyerl’s masked daughter delivers The Weather Underground Report) and climate all become fluid in what appears to be a post-GFC, post apocalyptic world.

Next to Liquidity Inc (2014, 30mins), The Guards (2012, 14mins) is quite formal—as close as you’ll get to a straight documentary from Steyerl—in which two black American gallery guards reveal their backgrounds as policeman and marine. Their language and the marine’s miming of his stalking and attack routine in the quiet white gallery rooms with their famous paintings bring home the police mentality and militarisation pervading the everyday. As the film proceeds, the guards’ attitudes and moves are almost threatening. Finally, we see Steyerl, seated, smiling, watching the guards at work, but they have been superimposed over the paintings and into their frames, supplanting the art, as in earlier scenes artworks had become live footage of police pursuit and war scenes.

Adorno’s Grey, Hito Steyerl

Adorno’s Grey (2013, 14 mins) is also neatly if more laterally constructed, documenting a formal attempt to find the grey paint beneath the white walls of a lecture theatre where the great Marxist cultural theorist Theodor Adorno taught until, in 1968, three female students walked to the lectern and bared their breasts, and he fled never to return. The film is part of an installation in a viewing space in which the screen is made up of large, leaning vertical planks in shades of grey. The black and white video itself is consequently shaded grey adding to the sense of ambiguity central to the film (why grey? why flee? why bother?). Smaller versions of the planks are found outside near two walls of text dating the history of protest as action or art.

Disappointingly, key Steyerl works (November [2004], Lovely Andrea [2007] and Free Fall [2009]) that were included in the Van Abbesmuseum in Eindhoven (Netherlands) do not appear in the Brisbane iteration of the exhibition. I’ve seen Lovely Andrea but not November and Free Fall, missing the opportunity to see how Steyerl self-critically positions herself as subject, performer and maker in each. There are DVDs available in Europe of Lovely Andrea and November. Time to invest in some reflective home viewing.

There’s a fine small catalogue of good essays accompanying this well-staged exhibition with abundant stills from the videos of this influential artist. It includes Steyerl’s widely delivered and published lecture “Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?” (you’ll easily find it online), a wonderful mind bender in which “digitisation slip[s] off-screen and enter[s] the material world” (Editor’s introduction, Too Much World) which, in turn, as in Liquidity Inc, becomes dangerously fluid.

Performance Now

Rose Lee Goldberg, author of the seminal book on performance Performance Art: From Futurism To The Present (1979) and founder and director of New York’s Performa festival, has curated a travelling exhibition of performances, some stand-alone screen works, others documentation. Most have been made since 2000. Irritatingly, there’s no catalogue, captions are basic, sometimes not even indicating country of origin, and there are blanks for all the links to artists on the website of Independent Curators International, the co-producer of the exhibition with Performa. Under these circumstances, for the committed viewer Performance Now just manages to work, piquing curiosity, sending the odd shiver up the spine or putting an idea into orbit.

Marina Abramovic’s Seven Easy Pieces (Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2005) comprises seven resurrected performances (including her own and works by Bruce Nauman and Vito Acconci) set on circular platform stages. The set-up of seven eye-level screens side by side on a gently curving wall suggests perhaps that Goldberg only intends us to dip into these epics. The videos of these durational works for the most part appear as still lives at seven hours each. After 15 minutes or so of standing with no capacity to (desecratorily?) fast forward and concern building about time limits, the eye is attracted to the screen on which the gilt-and-honey-masked artist cradles pieta-like a dead hare, sets up and demounts easels and blackboards, opens a trapdoor and taps the frame furiously before subsiding into stillness, hare in lap. It’s Abramovic’s recreation of Josef Beuys’ How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), regarded by some as the artist’s masterpiece. It is richly suggestive and strangely beautiful, even if experienced at a pronounced remove. These videos simply ignite a desire to have witnessed the performances. They are more homage than experience.

In a work seen in Australia in 2012, a grand piano is slowly rolled around a gallery followed by a curious audience. A circle has been cut from the grand’s centre and some two octaves of the relevant wires and keys put out of action. In the centre is a man, pushing the piano from the waist, leaning over the keyboard to play a piano reduction of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony back to front, using the dead keys percussively and plucking and stroking the strings. We fill in the missing notes in our heads and muse over the creation of an unfamiliar interpretation from Guillermo Calzadilla and Jennifer Allora (Stop, Repair, Prepare: Variations on “Ode to Joy,” 2008, Puerto Rico). In interviews (eg bombmagazine.org) the pair have cited their fascination with the relationship between music, sound and violence exemplified in the ode’s theme of ‘universal brotherhood’ alongside its quoted Turkish military band theme. More evident is the work’s playful resurrection and synthesis of 20th century avant-garde visual art tropes in the form of piano as readymade, piano desecrated (if not destroyed), piano prepared a la Cage and piano for performative installation.

I particularly enjoyed the political motivation evident in a number of works. In Regina José Galindo’s video, one of the show’s, most intriguing, in what appears to a be a Latin or South American city a young woman in black carries a bowl of red liquid, stopping frequently to dip a foot and leave red footprints along the streets and footpaths. Simple though it is, the association of Catholic culture with extreme forms of penance and pilgrimage is casually evoked but barely noticed by people the woman passes. Only later, having not registered or understood the gallery caption and searching for reference to the work online, I discover its title and meaning: A Walk from the Court Of Constitutionality to the National Palace of Guatemala, leaving a trail of footprints in memory of the victims of armed conflict in Guatemala, 2003.

A more overtly political work, And Europe Will Be Stunned/Mary Koszmary (Nightmares) (2007, 11 mins) by Israeli video artist Yael Bartana, is staged in the deserted, overgrown National Stadium in Warsaw. A suited young man at a microphone speaks to a small group of young people as if addressing a larger audience, low camera angles lending him stature. He declares, “Jews! We miss you!” The young people stencil “JEWS” onto the field. “Even when you left, there were those who kept telling you to leave,” he says. However, in the end the sense of enlightenment is diminished as the young people line up in dark uniforms with red neckerchiefs, suddenly evoking Stalinist or Zionist Youth fervour. It’s bitterly ironic, made in the manner of propaganda films of the 1930s-50s but with full-colour, feature film production values that tell us this is a film about now. Bartana was chosen to represent Poland at the 2011 Venice Biennale.

Liz Magic Lazer’s I Feel Your Pain (US, 2011, 80mins) records the recreation of interviews with famous people, including a bitterly funny television exchange between Bill and Hilary Clinton after the revelations about his infidelities. It’s performed in a theatre, the actors sitting with and moving about the audience with cameras trained on them, their images projected onto the cinema screen. With an adroit fusion of live verbatim theatre and parodic media technique Lazer incisively focuses on the rhetorical tactics and cliches politicians and political commentators deploy, especially when under pressure.

Among the more striking works on show is a modest two-minute film Ukungenisa (2008) that comes with significant post-colonial ramifications. A black woman (the South African artist Nandipha Mntambo) is transformed into a Mozambiquean bullfighter preparing to fight in an abandoned Portuguese arena. She wears not only the requisite outfit but also a large animal skin as if she is at once hero and victim, scraping a foot across the sand like an impatient bull.

Several works pivot around the modern family. Guy Ben-Ner’s widely seen (including on YouTube) Stealing Beauty (Israel, 2007) in which the artist and his wife and two children invade successive IKEA stores and inhabit display rooms is wickedly funny. The dialogue between family members focuses on consumerism and property (“Is Mom private property?”) with a mock-Marxist slant which is nonetheless apt. Stealing Beauty is a model of guerrilla filmmaking of the most amiable kind (Liz Magic Lazer also conducts filmed live performance interventions).

If Ben-Ner mimics conventional filmmaking, Ryan Trecartin runs wild with the camera: bodies lunge into frame, close-ups are in-yer-face and there’s a lot of dress-ups and dialogue that you have to grab at. And if Ben-Ner’s family seems quite normal, Trecartin’s fictional one, in A Family Finds Entertainment (US, 2004, 40 mins), is a high-level bizarre mix of folk ordinary and wild. The artist plays demented teenager Skippy (knife wielding, teeth blackened,) who is ordered to leave home by his “Snake” mother. He’s hit by a car, survives and parties with a wild girl, Shin, while being followed by a woman making a documentary about “medium-aged kids all over the world.” But narrative counts for little in this wild melange of home video, animation and vivid theatricality. What it adds up to is a sense of release from family life—if from one mad world to another. See it to believe it (sometimes found on YouTube).

Kalup Linzy’s black family soap opera All My Churen (US, 2003), built around a series of telephone dialogues, is not as visually delirious as Trecartin’s, but the dialogue and the artist’s convincing comedic playing of all the roles in various wigs, outfits and voices are likewise gripping in their excess.

In the foyer there’s a sculptural work by Brisbane artists Clark-Beaumont, the only Australians represented in Performance Now. It’s a carefully crafted, sharply angled rock face, a duplicate of the one that Sarah Clark slid down before being rescued by Nicole Beaumont while they were on a walking trip. The near-serious accident was re-created for the opening of Performance Now. A machine fault meant that the video was not showing during my visit. But reading the accompanying wall text and appreciating the sculpture, a friend commented that imagining the performance was oddly satisfying.

Big questions arise out of the Performance Now experience. Is this simply a video art exhibition? What does it actually have to say about performance today beyond the fact that art performance has diversified and is less precious than its forbears? Can an exhibition of performance on screen be meaningful without context? As Mike Leggett, driven online by the absence of an Experimenta Recharge catalogue, asks (see article), “Is the web now confirmed as rivalling the white cube, becoming the preferred place for exhibiting media art, simultaneously storing knowledge gleaned in steady accumulations of feedback?” You can see Performance Now (allocate a day) until 1 March and ask yourself.

Too Much World, The Films of Hito Steyerl, curators Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh in association with Annie Fletcher, presented in cooperation with the Van Abbemuseum and the Goethe-Institut Australia; IMA, 13 Dec, 2014-21 March 2015; ICI (Independent Curators International) and Performa, Performance Now, QUT Art Museum, Brisbane, 6 Dec, 2014-1 March, 2015

RealTime issue #125 Feb-March 2015 pg. 22