Five days in other worlds

Keith Gallasch: 2014 Perth International Arts Festival

Robert Wilson, Krapp’s Last Tape

photo Lucie Jansch

Robert Wilson, Krapp’s Last Tape

Transported from Sydney to Perth, and even further afield by the magic of art. Five packed days at the 2014 Perth International Arts Festival witnessing bracing performances—Robert Wilson in Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, my first experience of the wild creations of Russia’s renowned Dimitry Krymov, my second of flamenco radical Israel Galvan—and participating in Rimini Protokoll’s Situation Rooms, becoming an actor in the international weapons trade. The visual arts program was likewise immersive and culturally intriguing.

Krapp’s Last Tape

In near dark a man sits at a large desk. The sound of rain. Rain heavier and heavier. Thunder. Clouds in the high thin windows. The rain roars. It’s a hot day but here in the theatre we feel a chill. Partly visible, the man (Robert Wilson as Krapp) moves about the room, gesturing oddly, a slight lilt in the walk, returning to a tape recorder on the desk, reaching as if to activate it but swerving away. The rain is deafening now. Krapp gestures widely. Silence. Blue light through the windows. Krapp is ready to listen to his tapes, procrastination is apparently over, the imagined storm banished. We have been likewise prepared (as ever in Wilson’s works) to listen and to carefully look.

Revealed: a capacious Bauhaus-ish room with huge white shelves stacked with tape cases. Krapp, hair stiffly teased, eyebrows raised, white-faced, in white shirt, waistcoat, grey trousers, is straight out of a German Expressionist film of the 20s, save for the bright red slippers that play up his dancerly gait. Once he has our attention, Krapp commits to his task, reviewing a tape of himself at 39 years reflecting mockingly on his optimistic self at 20, and recounting his physical ailments, failure as a writer, unresolved relationship with a woman he met on a punt. He angrily discards the tape, attempting unsuccessfully to make a new recording—what is there to say? Instead he returns to the first tape, playing out into silence the recollection of love lost. Krapp’s Last Tape usually plays at around 35-40 minutes, here it’s for an hour, including the 15-minute storm. Wilson enlarges and extends Krapp’s prevarications—he dances in and out the light (the 39-year-old’s light was new and he delighted moving to and fro beneath it), sings at length with his (off-stage) neighbour, disappears to his kitchen, twice clowns obscenely with a banana (a fruit his 39-year-old self has trouble with, while at 69 Krapp, still sexually driven, sees an aged prostitute—“ better than a kick in the crutch”). Who would have thought the possessive Beckett estate would tolerate such elaborations, but various versions—an opera, an art music piece, film, radio and television versions—have been permitted.

As anticipated, Wilson’s version is greatly different from others. Some had been directed by Beckett himself, one featuring Rich Cluchey of the San Quentin Prison Drama Workshop; I enjoyed this one greatly at an Adelaide Festival. Atom Egoyan’s film version features a moving performance by John Hurt (available on DVD from the wonderful Beckett on Film series, 2000). There’s also an admired Harold Pinter account and the original and seminal Patrick Magee version (which you’ll find on YouTube). Wilson, like most of these performers, has the sonorous delivery apt for Beckett and the facility to switch gear from pathetic to nigh tragic to comic. (It was a pity that the sound mix of live and recorded voices in the opening performance in Perth was quite unbalanced, making the live voice less intelligible). While his account is less naturalistic than those of his forebears, and not as dark, it manages to be true to Wilson’s own art and to Beckett’s, towards the end drawing in close on Krapp and riding the flow of Beckett’s text so that we are touched by the sadness underlying the bitterness, denial and distraction we’ve witnessed. It’s fascinating that this Krapp keeps his distance from his recorder. For others the machine is an intimate.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Dimitry Krymov

photo courtesy Royal Shakespeare Company

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Dimitry Krymov

Dimitry Krymov, Midsummer Night’s Dream (As You Like It)

Another fantastical theatre experience came in the form of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (As You Like It) (director Dimitry Krymov, Russia) in which Shakespeare’s Mechanicals invade the auditorium of His Majesty’s Theatre with props (a huge tree trunk in parts, a functioning fountain spraying the audience), only to abandon them backstage and instead, suited, commence their performance of Pyramus and Thisbe with the ad hoc construction of two (wonderfully pliable) enormous puppets made from bits and pieces. They are ambitious—their version is ‘the’ orginal—and attentive to “inter-textuality.” They are meanwhile insulted by the indolent nouveau riche (all with mobile phones) behaving like aristocrats in the box seats, struggle with their wobbly creations, perform acrobatic feats and musical numbers, popular and classic, exhibit an obscenity—a bicycle-pumped-up erection for an infatuated Pyramus—and rather nervously make jokes about KGB murders (including that of Meyerhold) and current less than secret surveillance. The work is packed with a variety of performance practices, comedy and pathos, acute observations about life, art and class. It’s a crowd pleaser with ideas, passion and a strong sense of Russia as it is now, complex and surreal, not to mention dangerous.

In the end an actor sweeps the stage, attempting to brush into the wings a bevy of defiant young ballet dancers (children from Perth’s Steps Youth Dance Company) executing Swan Lake’s Dance of the Cygnets with poise and vigour. Finally an older woman from the audience who had objected to the work’s experimentalism and obscenity, realises that she recognises the actor, a man she is still attracted to. She offers him her card, hypocritically declaring, ”I love the avant-garde!” and exits. He lets the card fall to the floor.

Denis O’Hare, An Iliad

I was not entranced by Denis O’Hare’s award-winning An Iliad (A Homer’s Coat Project, US), by the laboured ‘virtuosity’ of the performance or the too orchestrated casualness of its framing. I thought it promising at the beginning as O’Hare, in a tired old coat and carrying a suitcase, jocularly channelled Homer (“Back then I could sing [The Iliad] in Babylonian;” “It went down really well in Gaul”) and located himself in the tradition of the bard, with some powerful archaic singing. Then, suddenly he’s in Troy, reliving the siege (“I knew the boys”), halting to comment of the private/public tensions that wrought its worst moments and deploying language bereft of the weight of the original: Agamemnon snidely to Achilles, “You’re so gifted”; Hector: “Bitch that I am.” Not content to sustain The Iliad as a work in the oral tradition, O’Hare adds a list of great wars across the centuries up to and including Australia’s involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, uttering a litany of Australian towns, the homes of our soldiers. O’Hare revels in his telling of an oft-told tale, without, it seemed to me any special insights or a sense of poetry. If you want that you have to turn to the late Christopher Logue’s inherently dramatic and daring (including his play with page space and typography) adaptation of selected books of The Iliad beginning with War Music in 1981 (I recorded it for blind listeners in the mid 80s, quite a task) and four more instalments subsequently.

Israel Galvan, La Curva

Flamenco innovator Israel Galvan (Spain) as ever demonstrated in La Curva his capacity to dance the dance while undoing it, creating commentary on the form along with images rich in thematic potential. On stage is a grand piano and five high stacks of chairs. Galvan topples one and the work begins. Eerily, the others seem to crash of their own accord, and so finally does the dancer. On that path his expert dancing becomes engrossingly stranger, duetting with brilliant experimental pianist Sylvie Courvoisier and traditional singer Inés Bacán (“the two together form my idea of the female artist,” program note) and Galvan’s rhythm accompanist, Bobote. The presence of small blocks of rosin on the forestage that Galvan stomps in to guarantee his grip on the floor presages the final act when he not only kicks up a huge cloud of the stuff centrestage but is totally covered by it as he falls to the floor, on his back, his arms and legs still in motion. Stillness. No sound. Galvan says that La Curva, a work punctuated with quiet, was “born out of my familiarity with silence.” The title refers to a concert of “Cubist” flamenco, with stacked chairs, by the dancer Vicente Escudero in 1924. Galvan thus lays claim to flamenco with a radical heritage while pushing ahead with its revitalisation.

Barking Gecko, onefivezeroseven

Perth’s Barking Gecko Theatre Company’s onefivezeroseven reveals the joys, anxieties, suffering, fantasies and, finally, political will of teenagers on the edge of adulthood. The play is based on extensive surveys of teenagers focusing on their possessions (1,507 is the average). In a series of monologues these objects become the starting points for revealing much about their owners that is very private. Acting, movement (Danielle Michich) and vivid techno-design and music are tautly integrated in a kaleidoscopic encounter with individual lives interpolated with group playfulness, heightening the sense of vulnerability in being alone while at the same time being governed by networks defined by obligation and intimidation as well as security.

In one ‘what if’ fantasy, participants in a furious collective dance drop out one by one into stillness, as if dead, inspected by the lone male left who dances on to a melancholy score. Other games involve playing hide and seek with childish glee. A girl rattles off statistics about the scale of the cosmos, defiantly lecturing us that “[teenagers] know what’s real and what’s not,” and, executing a head stand, declaring, “we CAN recognise beauty.”

Boundless energy suggests the potential of the young: hearts massively pounding as one, bodies sharing exuberance and exhaustion in contrast to souls hiding beneath blankets or seeking refuge in precious headphones (“they let me be”). Secrets tumble out, betrayals, victimisation, rivalries, sexual anxieties—the discovery that sex is not always intimate, that blow jobs are not even thought of as real sex.

The work finally turns to a litany of demands for the right to vote at 16, given “we can fuck, have a baby,” drive at 17 and pay tax on jobs at 14 and 15 years of age. The cast don Tony Abbott masks in a mock military ‘get rid of Tony’ routine prior to the telling of one last story (underscored with an overly melancholy cello score) told by a young Lebanese immigrant labelled as a terrorist: “Go home!” “Australia is my home.” The work ends with a cheerfully bold call from the young to their elders for a change of attitude and new rights for teenagers.

While acknowledging its emotional frankness and the high calibre of its direction (John Sheedy), acting and movement, I thought onefivezeroseven not unlike old school theatre-in-education, unapologetically didactic and structurally schematic. For all its research and the number of interviewees, the work also felt rather limited in scope. Although characters are quite different from one another and some very wounded and isolated, they all come together as an unlikely single voice, minus cultural and serious political differences.

Situation Rooms, Rimini Protokoll

photo Jorg Baumann

Situation Rooms, Rimini Protokoll

Rimini Protokoll, Situation Rooms

Inside a two storey building constructed in an ABC TV Perth studio, wearing headphones and holding iPads, for 70 minutes we encounter and engage with weapons traders, bankers, generals, terrorists and activists in Europe, Mexico, Pakistan and Sierra Leone. We handle guns, operate drones, don bullet-proof vests (or help others into them), shake hands with each other in various roles and watch on iPads the people whose stories we are ‘enacting’ in the very same rooms we occupy. Some we only hear (too dangerous for them to appear), some address us directly (I became the Director of Deutsche Bank, sitting in his office confronted on my screen by an actual leading anti-cluster bomb activist). Other contributors to the work simply appear onscreen like us, with headphones and iPhones, as if reviewing their own experiences.

In one of the more disturbing experiences in Situation Rooms I’m on a bed in a small, immaculately realised emergency medical centre after ‘being wounded.’ Another audience member decides on the level of my injury and attaches the appropriately coloured marker to my body.

Hearing voices and seeing faces from a variety of political circumstances and points of view was at times unnerving. Some rooms generated sympathy, in some you were complicit in wrong-doing and in others, in Africa and Mexico, you found yourself in altogether alien worlds. Situation Rooms is about projecting yourself into unlikely and sometimes unconscionable scenarios, an activity in which you want to understand the strangers you encounter. In the end however it’s an impressionistic experience, given the number of people you briefly meet, the variety of roles you kind of play and the amount of time you peer at your screen in fear of getting lost. It also felt distancing watching some of the work’s real-life participants onscreen doing just what we were doing, screens in hand, moving on our various trajectories. Humphrey Bower in Crikey.com’s Daily Review wrote, “The iPads effectively separated us from each other, the work itself and its subjects. Their screens rendered us as isolated spectators rather than audience members, let alone true participants in the unfolding of events. In this sense, Situation Rooms ends up being complicit in the very situation it criticises.” Of course, some of the roles we played were clearly designed to make us feel uncomfortably complicit, others sympathetic, though none with enough information or exchange to generate empathy. Situation Rooms, framed as a game, plays at the edges of empathy, placing us in ‘what if’ scenarios. It is about us, not ‘the others,’ or is at best a first step towards understanding the lives of those engaged or entangled in the arms industry.

For a survey of Rimini Protokoll projects and an interview with one of its directors Stefan Kaegl see “Documentary theatre as action,” on the RealTime blog realtimetalk.net.

Ryota Kuwakubo, The Tenth Sentiment, John Curtin Gallery

Ryota Kuwakubo, The Tenth Sentiment

In a dark room, a small moving beam of intense light close to the floor cuts through the space, throwing up and distorting the shadows of small objects—a field of pencils, a ball of steel wool, a light globe—writ large on the gallery walls. The light is affixed to a tiny electric train-like device running on a track. At the end of the journey it hurriedly backs up to its starting point, or in visual terms, “rewinds’ what we’ve just seen, as Chris Malcolm, director of the John Curtin Gallery, put it when he guided me through its two festival works.

With its mobile shadow play Ryota Kuwakubo’s The Tenth Sentiment evokes the pre-cinema of the 19th century. The apparently simple set-up yields analog magic but, as Malcolm tells me, the circuitry and the fine tuning is complex. The results as the ‘train’ moves slowly across the landscape are constantly surprising; we witness the mutation of everyday objects into strange buildings, cities, forests and remote landmarks. A journey through an inverted colander conjures a Futurist fantasy, filling the room with its expanding and then contracting architecture. The perceptual play is pure delight.

Paramodelic Graffiti

photo Brad Coleman

Paramodelic Graffiti

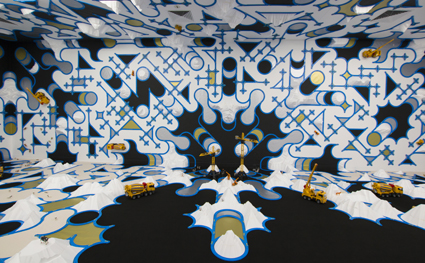

Paramodel, Paramodelic-graffiti

Also at Curtin and occupying its large gallery is another immersive, visual wrap-around Japanese work, hand-crafted on the floor, walls and ceiling—Paramodel’s Paramodelic-graffiti (artists Yasuhiko Hayashi, Yusuke, Nakano). As with the 10th Sentiment there is an interplay between the real and the virtual. Margaret Moore, the festival’s Visual Arts Manager, writes in the catalogue, “Intensive computer design paves the way for [Paramodel’s] installations, yet when it comes to the actual realisation, their work attains a quizzical balance between organic drawing and high-end design.”

Again rail tracks feature, coursing across the space in recurrent patterns and variations that evoke traditional and modern Japanese pattern-making, the spaces between saturated with blues, whites and blacks. This ground is occupied by hand-cut polystyrene mountains (also hanging from the ceiling and thrusting from the walls), tall toy cranes and small animals (including Australian mammals and lizards). For all its sophistication, the work, as Moore writes, “seems to retain a child-like view of the world.” And a teenage one too given their work’s resonance with graffiti and the inventiveness of Manga. Aptly, in an adjoining room there’s a space in which children are provided by the artists with the tools to create their own landscapes which are recorded from above and can be played back at speed.

Do Ho Suh, Net-Work

On the shore of the Swan River, a large net hanging between poles glitters by the sparkling water. You draw closer, noticing a certain fixity, even though there’s the slightest of movement in the breeze: the net comprises thousands of identical figures, apparently metallic, arms and legs stretched wide and threaded together. From one side of the net they appear silver, on the other gold. The net trails into the water, one end bunching up on the sand, convincingly like a real net. Korean artist Do Ho Suh’s Net-Work serenely evokes the ephemerality, continuity and collectivity of labour and the twinning of craft and artistry.

William Kentridge, Refusal of Time

photo Aaron Bradbrook

William Kentridge, Refusal of Time

William Kentridge

As ever, the precise meanings of William Kentridge’s engrossing creations (drawings, films, animations, puppetry, installations, operas and combinations of these) remain fascinatingly elusive, despite a plenitude of transparent symbolic markers. Just how they connect is another matter. The Refusal of Time is a huge work occupying the whole of the main PICA space with five screen projections (filmmaker Catherine Meyburgh) on three walls of Kentridge’s animations and staged performances (choreography Dada Masilo) with enveloping music (Philip Miller) and dramaturgy by physicist and historian of science Peter Galison. I was taken in particular with the costuming (touches of Bauhaus inventiveness), dancing and transformations in the strange domestic scenes, as well as with the overall sense of time in and out of synch, measured against the stars, the beat of metronomes and the epic march of shadows of human beings bearing goods and possessions and led by a hauntingly scored brass band. Despite several visits, there was much that I hadn’t integrated into my understanding of The Refusal of Time, save that given its constant shuffling of histories social and scientific, South African and beyond, we haven’t yet faced up to time’s relativities. You can glimpse the work and Kentridge discussing it on YouTube.

Bali: Return Economy

At Fremantle Arts Centre, Bali: Return Economy, reflects and builds on a long-term relationship between Western Australia and Bali dating back into the 19th century, bringing together works by artists with a view to extending and expanding the relationship. I met the show’s curators, FAC’s Ric Spencer and traditional Balinese art expert and collector Chris Hill (Survival and Change, Three Generations of Balinese artists, ANU, 2006).

Ric Spencer says, “the relationship between Bali and WA is a pivotal one—the number of people coming and going and the cultural influence is substantial. There’s a sense here in the media of ownership of Bali and what goes on there: I was wondering why that was. In the 18 months of developing it on our travels the show has developed on its own lines. For us it’s become a conversation, a departure point for broader discussions about the impacts of tourism and how Balinese culture has influenced West Australians.” Hill adds, “It takes less time and it’s cheaper to fly to Bali than Sydney, and we’re attracted to Balinese culture. This culture is being threatened by overdevelopment and 1,000 West Australians going there every day—which is extraordinary. It’s a very different culture on our doorstep. The work in the show dips into tourism and the holiday experience but also collaborations in art and trade. The influences have come back in art, architecture and furniture.” The curators encountered a thriving, networked contemporary arts scene in Bali, fuelling their desire for more of it to come to Australia where it is, they say, seriously under-represented.

It’s a deeply engaging show, one with a sense of great energy, which is not surprising given that the artworks from Bali are often inherently infused with a sense of ritual. Hill points out to me a cartoon (Soccer in Paradise, 2013) by Jango Pramatha in which a match has drawn to a casual halt as a ceremonial parade crosses the pitch, highlighting not only a blend of continuity and change but also a ‘no worries’ Balinese mentality. In a similar vein, in beautiful pinks and pastel blues and in a dynamic rendering of the Kamasan painting tradition, Ketut Teja Astawa’s Sterile Environment (2013) portrays a dancing rajah oblivious to the tiny (in his world) earth mover pummelling the base of a tall adjacent tree. Of the several paintings in the show in the style of the village of Kamasan, Hill explains, “thin cotton is sized with a rice paste and traditional materials are used—black Chinese ink applied with a bamboo pen and paints made from natural materials. The paintings aren’t old but they are traditional.”

Wayan Upadana’s Couple in Paradise (2013) is one of two small and precious sculptural works (polyester resin, car paint) featuring pigs bathing in chocolate; not only is it a critique of luxurious living but also of cultural carelessness: the vessel is a traditional offering bowl.

The centrepiece of Nyoman Erawan’s altar-like installation is a glass cast of the artist’s head, Wajahku (2012) within which sits another masklike face, straight out of traditional Balinese dance, evoking, Hill tells me, an inner god-self. However as you move around the head, from the top of which rises a bundle of incense sticks, you see that the interior comprises electronic circuits and wiring. Opposite the Erawan work is Perth artist Linda Crimson’s vivid altar of consumption and culture rising to the ceiling, layered with objects purchased in Balinese markets: toys, clothing, Micky Mouse inflatables, brassieres, domestic items and much else. There’s an easy mix of past and present here, while Erawan’s self-portrait suggests tensions between the spiritual and the technological.

I Wayan Bendi’s Twin Towers (2001) is one of the most striking works in the exhibition, a large-scale depiction of the events in New York of September 11, 2001 entirely transposed to Bali, but as an island more of the past than the present—mythological figures, ceremonies, temples, elephants, quaint versions of aeroplanes and the Twin Towers, vast crowds and, as Hill points out to me, an overall patterning and a doubling of figures, lending the swirl of action great cohesion. The event is given a spiritual aura compounded by the exquisite detail provided by the traditional painting technique.

The most affecting work in the show is Bom Bali (2006), a small painting by Dewa Putu Mokoh in which bodies have been tossed around by the bombing of 12 October 2002. Stylised, twisting flames, representing explosions in the centrally placed vehicle, emit dotted lines, trajectories to further fires amid the crowd of contorted bodies: limbs detached, tongues hanging from mouths. There is, however, no gruesome detail, instead an aura of innocence, the simply delineated figures almost childlike, the colours of their clothes pastel soft. Hill tells me that the artist usually portrayed village life and intimate domestic scenes, but “as far as I know, it is his only painting that focuses on an historical event. It’s painted with great tenderness. Once you realise what it’s about it becomes shocking.”

There are many other captivating works in the exhibition, finely executed pieces in traditional modes, John Darling’s documentaries of Balinese culture, Ni Nyoman Sani’s ironic fashion pieces and Annette Seeman’s sculptures and family photographs in which the artist’s father is seen on a tiger hunt in the 30s. While enjoyably nostalgic, and speaking of a long connection between WA and Bali, these images are indirect reminders of the grip of colonialism and disparities in power and wealth. How much has changed? Bali: Return Economy is a finely curated, well-staged (exhibition manager Desak Dharmayanti) and culturally intense experience, yielding much pleasure and reflection.

The festival’s visual art program—which also included Richard Bell’s Embassy at PICA (until April 27 with Kentridge’s The Refusal of Time) featuring striking large scale paintings and a tent housing video works—had a sense of geographic and cutlural cogency, embracing highly engaging artworks from Japan, Korea, South Africa and Bali and Australia.

–

2014 International Arts Festival, artistic director Jonathan Holloway, Perth, 7 Feb-1March

Keith Gallasch was a guest of the Perth International Arts Festival. He thanks the Festival’s Visual Arts Manager Margaret Moore in particular and the curators of the exhibitions he visited.

RealTime issue #120 April-May 2014 pg. 17-19