Flow maps & heightened states

Andrew Fuhrmann, dance at Asia TOPA 2017

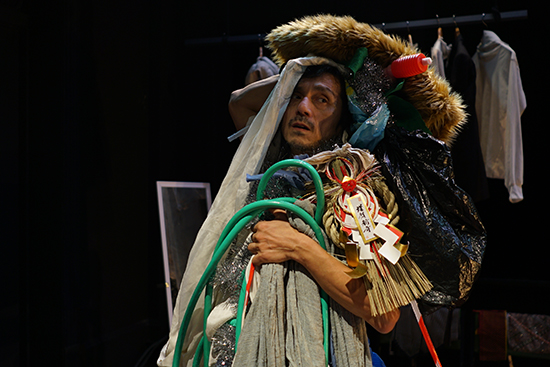

Yumiko Yoshioka, Evocation of Butoh, Asia TOPA 2017

photo Mifumi Obata

Yumiko Yoshioka, Evocation of Butoh, Asia TOPA 2017

The performance of extreme or heightened states is and always will be a fascination. It could be an exhibition of unleashed passions or a feat of physical endurance. It could be a celebration of deeply sensual experiences or a ceremony of spirit possession. It could be ecstasy or it could be trance-like dissociation. The thrill for the audience is the same: the spectacle of mind and body suspended by a thread above an insensible abyss.

And ever since Dionysus walked into Thebes with jangling bells and ivy garlands, this fascination has been a key theme of cross-cultural exchange in the performing arts, West to East and East to West. The history of ritualised and formalised performance traces hemispherical flows, movements back and forth, from religious dance-drama through theatres of cruelty to experiments in psychophysical transformation and beyond.

So it should be no surprise that this theme is so prominent in the program for Asia TOPA, a festival highlighting Australia’s many cultural and artistic relationships with Asia.

Evocation of Butoh: Yumiko Yoshioka, Before the Dawn

One necessary site of exploration is Butoh. This highly physical Japanese art form developed around a key axis of East-West thinking and practice, with ideas drawn from Artaud and Genet among others translated into a post-war Japanese context. Here, extremity is manifested in the need, as Yukio Mishima once said, to scrape all vestiges of habit or convention from the dancing body.

The Evocation of Butoh program at La Mama, produced by Yumi Umiumare, presented five short Butoh dances from local and international artists, as well as a series of workshops. The high point of this mini-festival was an engrossing performance by well-known Japanese choreographer Yumiko Yoshioka—now based in Berlin—titled Before the Dawn (2002).

Yoshioka confronts us with a catalogue of nightmare imagery, including twitching limbs, puppet-like prancing, shadow play, extravagant gurning and erotic grotesqueries, all of which she gives a unique comic inflection. The recurring scene where Yoshioka uses her hands to mime a pair of demonic swans pecking at her face lingers long after the performance has finished. There are also two neat piles of sand on stage, a vision somehow resonant with Hiroshi Teshigahara’s 1964 film Woman in the Dunes.

Yoshioka has a masterful eye for the composition of striking stage pictures with a kind of cinematic stylishness and enthralment. And the fact that Before the Dawn still seems fresh despite the recent deluge of mainstream horror films with Butoh-inspired aesthetics underlines the ongoing vitality of the form.

Dancing with Death, Pichet Klunchun, Asia TOPA 2017

photo Mark Gambino

Dancing with Death, Pichet Klunchun, Asia TOPA 2017

Pichet Klunchun, Dancing with Death

Dancing with Death is a subdued and somehow unconcluded piece in which choreographer Pichet Klunchun uses his own attempt to transform classical masked Thai Khon dance into a more contemporary internationalist style as a metaphor for the political situation in Thailand.

The work begins with brightly costumed and masked figures darting around the stage like a troupe of Phi Ta Khon ghosts. This merry prelude with its folk-style capering soon gives way to something more austere and muted as the colourful spirits recede into the wings, replaced by six dancers in mundane costumes of white, beige and brown.

Dancing with Death, Pichet Klunchun, Asia TOPA 2017

photo Hideto Maezawa

Dancing with Death, Pichet Klunchun, Asia TOPA 2017

The centrepiece of the work is an enormous undulating track, roughly oval-shaped, elevated, set well back from the audience and dimly lit. This represents a kind of limbo around which the dancers walk or skip or sprint. (A state of limbo is one way of describing Thailand since the political crisis of 2013.) Sometimes the dancers pause to peer over the edge of the track or gesture plaintively to one another or to the gods above. Sometimes there is unison or a glimpse of Khon technique, but always there is the discipline of the track.

This is an endurance piece, with the dancers eventually exhausting themselves and dropping out of the loop until there is only one left, Kornkarn Rungsawang, jogging indefatigably around and around. On the night I saw it, the audience somehow missed the cue that indicated the performance was over; we ended up watching for at least an extra 10 minutes until Arts Centre staff intervened. For Rungsawang it must indeed have felt like being trapped in a zone of infinite uncertainty.

Attractor, Asia TOPA 2017

photo Gregory Lorenzutti

Attractor, Asia TOPA 2017

XO STATE DUSK: Dancenorth, Lucy Guerin Inc, Senyawa, Attractor

The XO State series transforms the stage area of the State Theatre into a performing arts club where punters can buy food and drink and see one major performance and several short ones every night. Choreographed by Gideon Obarzanek and Lucy Guerin with music by Javanese duo Senyawa, Attractor is the first of the major performances in the series.

The music is an eerie kind of experimental hardcore, with amplified and distorted riffs played by Wukir Suryadi on crude homemade stringed instruments [built out of redundant farm equipment. Eds], and with theatrical growls and shrieks provided by Rully Shabara. The pair forces an associative link between the throat-shredding vocal acrobatics of contemporary heavy metal and pan-tribalist world music.

The eight dancers from Dancenorth illustrate this link, taking us at high speed from the rock concert mosh pit to the worship of strange new fetishes. This leads us to the depiction of a moment of communal awakening as a clan of some 20 extras emerge from the audience to join the dance. These volunteers—taking direction via earpieces—provide a sort of chaotic backdrop to the lunging and stamping of the ensemble dancers.

It’s a fine performance with an irresistible energy; but it is impossible to believe that the performers, let alone the volunteers, really achieve the ecstatic release promised in the program notes. The choreography is too shrewd, too aware of itself. And so perhaps in this instance the rhetoric of extremity and sublimity has more to do with marketing than creative practice.

TAO Dance Theater, ‘6,’ Asia TOPA 2017

photo Mark Gambino

TAO Dance Theater, ‘6,’ Asia TOPA 2017

TAO Dance Theater, ‘6’ and ‘8’

That is not something you could say of Chinese choreographer Tao Ye, who is committed to an artistic process in which the individuality of his dancers appears to disappear entirely. In the two pieces by Tao presented as part of Asia TOPA, the dancers are placed in a line and perform identical movements, and in both pieces their faces are obscured. Personality disappears into a larger organic unit, submerged by the all-but-perfect sameness of the performances.

In ‘6,’ the dancers stand toward the back of the stage at a slight angle to the audience. Rooted to the spot, they toss themselves back and forth like bottom-dwelling weeds in a dark oceanic trench, each one bending from the waist, rolling and whirling arms, torso and head. With a nerve-jangling score by folk-rock composer Xiao He and moody lighting by Ellen Ruge, the piece evokes feelings of danger and mystery. In the second work,’8,’ the dancers lie on the ground and ever so gradually shift themselves backwards. It’s a little like watching a fractal unfolding as the complex series of pelvic lifts and leg twists repeats and the dancers recede upstage.

The thought of the effort required to master these repetitions is overwhelming, but perhaps this is the point—to let go of the part of yourself which feels overwhelmed. “My pieces take a horrendous amount of time to rehearse,” says Tao. “They may not have much of a message to convey but are certainly a process.” And it’s a remarkable process, but it’s fascinating how the absolute discipline demanded by Tao Ye can also seem like the most dangerous kind of liberation, like the ecstasy or rapture of a zealot.

Takao Kawaguchi, About Kazuo Ohno, Asia TOPA 2017

photo Naoto Iina

Takao Kawaguchi, About Kazuo Ohno, Asia TOPA 2017

Takao Kawaguchi, About Kazuo Ohno

Repetition is also the theme of Takao Kawaguchi’s homage to Kazuo Ohno, presented at Dancehouse. Ohno was one of the founding figures of Butoh and there are extensive archives documenting performances throughout his career. The works which Kawaguchi recreates, drawing on archival footage, include Admiring La Argentina (1977), My Mother (1981) and Dead Sea, Ghost, Wienerwaltz (1985).

Here we have a simple contrast between two different heightened states of being. On the one hand, we have the Butoh master, creating visceral and highly personal modes of self expression. On the other hand there’s the archivist, the one who is passionate about repetition and puts his faith in video recordings and photographs.

And yet the contrast is not really so simple. Unlike Tao Ye and his dancers, Takao Kawaguchi does not appear to believe in the possibility of perfect repetition. Because he uses audio from the original performances as part of his sound design, we can’t help but notice small discrepancies in Kawaguchi’s performance. For example, we hear the sound of Ohno landing, after a short leap, moments before Kawaguchi himself lands. This gives everything in About Kazuo Ohno a slightly melancholic air. It is a special kind of mourning for the master, and an acknowledgement that the archive must always be incomplete.

The final image of the performance is a short video of a carved puppet of Kazuo Ohno held by his son Yoshito Ohno, swaying gracefully to the sound of Elvis Presley’s “Can’t Help Falling in Love.” The passions of the past become curiosities for the future, and what was once so extremely alive is now a drab little puppet. It is, in any case, a sad and tender moment.

From Supersense to Asia TOPA

What is the position of the audience in these performances or depictions of extreme states of being? Are we only fascinated observers, admiring from a safe distance? Or are we vulnerable? Can the performance of heightened states catalyse an extreme transformation?

Performing arts events are, of course, communal experiences, and there is always the possibility of emotional contagion or affective resonance; but the transmission of intense or heightened feeling is difficult in the context of a large cosmopolitan arts festival where performances are inevitably contoured by multiple layers of bureaucracy and the pressures associated with touring. Does this mean we inevitably encounter these performances as high culture voyeurs, browsing exotic experiences, thrilling to the sight of other people in extremis?

Perhaps it does. Here it is worth noting that Asia TOPA is essentially the child of Supersense, a one-off event held at the Arts Centre Melbourne in 2015. It was billed as a festival of the ecstatic, dedicated to exploring extreme and sublime horizons of human experience. A number of the artists at this year’s Asia TOPA festival, like Senyawa and Tao Ye, were also programmed as part of the earlier festival, and many of the organisers behind the scenes are the same.

The centrepiece of Supersense was Kuda Lumping, an extraordinary ritual trance performance involving a troupe of Indonesian dancers and a shaman from Batu in East Java. During the three-hour spectacle, the performers, apparently possessed by ancestral spirits, carried out extraordinary physical acts of strength and endurance, such as eating glass and hot coals.

The Supersense festival was promoted as an opportunity to experience the excitement and impact of ecstatic performances. “Supersense is an emporium for ecstatic experience,” declared Sophia Brous, curator and artistic associate at Arts Centre Melbourne, “a durational festival-as-theatre that will fill audiences with wonder.”

Some of this language of shopping for new marvels is still present in the marketing for Asia TOPA, particularly in the XO State program, curated by Gideon Obarzanek, the director the Kuda Lumping spectacle. But Asia TOPA promises to be bigger than this. Yes, there is still a certain amount of wilful confusion between the presentation and the representation of extreme states, and some convenient ambiguity about whether it is possible for audiences to participate in the ecstasies of the performers or whether we’re simply being invited to gawp at them. But the shift in emphasis allows for a more critical engagement with the theme of heightened states.

Takao Kawaguchi, About Kazuo Ohno, Asia TOPA 2017

photo Naoto Iina

Takao Kawaguchi, About Kazuo Ohno, Asia TOPA 2017

Think of About Kazuo Ohno, for example. Although Kawaguchi is committed to upholding the legacy of the Butoh master, his performative relationship to the heightened and stylised emotionalism of Ohno is deliberately ambivalent. He confronts the audience with intellectual problems as well as intensive or affective ones.

There is no doubt that Asia TOPA could include more of these sophisticated critiques of the performance of ecstatic experiences and transformations. There is, after all, plenty in our collective fascination—both West and East—with ancient ceremonies, spirit possession and transcendental experience that demands examination.

–

Asia TOPA: Evocation of Butoh: Before the Dawn, choreography Yumiko Yoshioka, music Zam Johnson, Kenichi Takemura, lighting Joachim Manger, La Mama Courthouse, 11-12 March; Dancing with Death, choreographer, director, designer Pichet Klunchun, lighting Asako Miura, sound Hiroshi Iguchi, costumes Piyaporn Bhongse-tong, dramaturg Lim How Ngean, Arts Centre Melbourne, 2-4 March; XO STATE DUSK: Lucy Guerin Inc, Dance North, Senyawa, Attractor, choreographers Gideon Obarzanek, Lucy Guerin, music Senyawa (Rully Shabara, Wukir Suryadi), lighting Ben Bosco Shaw, costumes Harriet Oxley, audio design Nick Roux, Arts Centre Melbourne, 22-26 Feb; TAO Dance Theater, ‘6’ and ‘8’, choreography Tao Ye, Music Xiao He, lighting Ellen Ruge, Ma Yue, Arts Centre Melbourne, 22-24 Feb; About Kazuo Ohno, concept, performance Takao Kawaguchi, choreography Kazuo Ohno,Tatsumi Hijikata, dramaturgy, video, sound Nato Iina, lighting Tosho Mizohata, costumes Noriko Kitamura, Dancehouse, Melbourne, 25-6 Feb

RealTime issue #138 April-May 2017