fragility and responsibility

douglas leonard is embraced by clare dyson’s being there

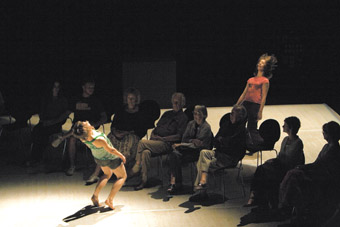

mily Amisano, Trish Wood, Being There

photo Fiona Cullen

mily Amisano, Trish Wood, Being There

IN THE PAST 18 MONTHS, INDEPENDENT ARTIST CLARE DYSON HAS PRESENTED THREE MAJOR WORKS OF DANCE THEATRE, EACH OF THEM DEALING WITH SITUATIONS IN EXTREMIS, OR AT LEAST IN THE LATEST CASE, FRAUGHT. THEY ARE CHURCHILL’S BLACK DOG, ABSENCE(S) AND, NOW, BEING THERE. THE FIRST OF THESE UTILISED CONVENTIONS OF CHARACTER (ALBEIT IN A CONTEXT WHERE THE CONCEPT OF CHARACTER WAS UNDER STRAIN); THE SECOND IMMERSED THE AUDIENCE IN AN INSTALLATION WITH OVERLAPPING MEANINGS DEPENDENT ON THE POINT OF VIEW. BEING THERE WEAVES PURE DANCE AND A RECORDED SPOKEN NARRATIVE INTO A SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL MOSAIC. IT WAS DEVELOPED AT TANZFABRIK IN BERLIN WHERE IT HAD AN INITIAL SHOWING.

These three works add up in diverse ways to a consistent, heuristic theatre of ideas based on Dyson’s investigation of audience agency and heightened by an unashamed proclivity for the potent poetics of Romanticism. Her rigorously conceived work is always sensitive to the surprising complexity, the mystery, the flawed beauty and fragility of life.

Dyson is canny in her choice of like-minded collaborators, including Mark Dyson (lighting) and Bruce McKniven (design). The circumscribed performance space of this new work is an ellipse delineated by muted lighting and a surround of chairs, a minimalist configuration that nevertheless gradually assumes a meaningfulness compounded by the failure of different geometrical planes to meet and the syntactical sense of ellipsis whereby words are left out and implied. There are gaps in the seating arrangements as transit points enabling the dancers to move here or there. As if in the complete intimacy of a dance studio, the dancers are within reach, and the audience is face to face.

Being There is about a woman who has an affair in a foreign country (over there), betraying her husband at home here in Queensland. Her predicament is that she is at a moral and artistic impasse. “When she was younger, she imagined the purpose of art was to move. Audiences, I believed, want to be discomforted. Move where? She wonders now.”

Being There constitutes a kind of dream fugue, a non-linear series of glimpses from past events. It plays on the dancer/text relationship, and portrays a struggle for mastery. Writer Siall Waterbright’s dispassionate vignettes amount to a cool appraisal that the unnamed woman cannot be there, wherever she is. Ironically the unseen woman’s infidelity is a poignant quest for visibility. By contrast, the dancers take a stand in the here and now, not standing in for the text. They choose to be present, authentically themselves, introducing themselves to the audience, even taking time for a water break. But sometimes the text gains ascendancy and the performers are over there. Lyrics to a song are in a foreign language. A woman removes her knickers, or strikes matches, illuminating, as Dyson says, “the domesticity of everything.” Sometimes the vocalized text takes centrestage, relegating the performers to the dark. Dyson conducts this antiphony seamlessly.

The two performers, Emily Amisano and Trish Wood, are personable, casually dressed, just two young women who dance beautifully, and beautifully together. They double relations in the text, traverse the same emotional territory, but as themselves, they unnerve us. We are proximate to them, breathing with them. They are falling women. They really cry, blow their noses, bruise themselves and slap the floor in an anguish which refracts rather than reflects the text. They are so committed that we are plunged to the depth of our own resources of memory and desire in order to meet them, and ultimately to realise that our own moral situation is fatally compromised or at the least exigent. As we leave, we can only match the “uncertain dignity” of Dyson’s protagonist. For a little while we cannot look each other in the eye.

Dyson has a dangerous flair for not allowing the audience to resile. Hers is an existential art. The title Being There alerts us to the dialectical relationship with Absence(s). In that earlier work Dyson eviscerated us by dramatically conveying the contingency of human existence, turning us into hollow men and women forever haunted by loss and death. In effect, denying our presence. Being There seemingly rejects the Sartrean take on being-for-others, or existing purely in terms defined by the Other which is so problematic for her fictional protagonist. Instead, an open invitation is issued to be fully present to a face to face encounter by directly challenging the stance of the audience as uninvolved observers. When Dyson’s art moves us, it moves us to ethically new positions. We are moved by the naked intensity of the live performers, and even sympathise with the one who is not present. We care for them all, and want to take responsibility for them. This is the possibility for an ethics defined by the philosopher Levinas.

Heidegger points us towards her method. Clare Dyson is at pains to provide a ‘clearing’ where “we can apprehend the being of a being, apprehend the being as it is, where it is.” To pull this off is wonderful and, I think, important. Art wasn’t meant to be easy. If you have the taste for this sort of thing, it sure as hell beats shopping.

Being There, creator Clare Dyson with dancers Emily Amisano, Trish Wood, writer Siall Waterbright, designer, Bruce McKniven, lighting designer Mark Dyson; Judith Wright Centre of Contemporary Arts, Brisbane, Dec 12-15, 2007.

RealTime issue #83 Feb-March 2008 pg. 43