Framing trauma, fear & love

Chris Reid: Adelaide Festival: Trent Parke, The Black Rose

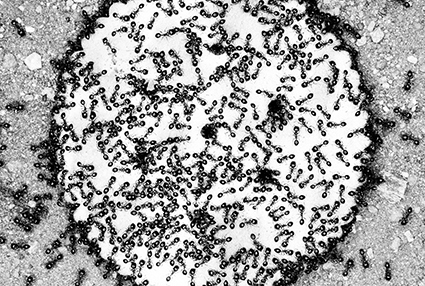

Trent Parke, Ants on Jatz cracker biscuit, Dampier WA, 2011

Trent Parke/Magnum Photos

Trent Parke, Ants on Jatz cracker biscuit, Dampier WA, 2011

In Trent Parke’s The Black Rose, we first see walls covered in a spectacular black and white museum-style panorama of the sky at dusk onto which cut-out images of birds, bats, insects and even fish are mounted. Some of the creatures ‘fly’ outside the picture space. In the explanatory text, Parke says the image is a representation of a dream he had.

In the next room, he begins to tell the story of his life and of the origins of his work. Here we begin to appreciate the massive scale of the exhibition which unfolds as a sequence of chapters involving many hundreds of images in rooms curated thematically. The third room is dimly lit and filled with black and white images—insects in the night sky against a background of stars, an illuminated spider web, the glowing eyes of black cattle in near darkness, crabs on a shore and a video of moths fluttering around an outdoor light. This room seems to be about illuminating the teeming life of darkness.

The next room is brightly lit and the work of a different character, emphasising childhood and family. Beginning with a large, vivid picture of his wife, photographer Narelle Autio, and newborn baby moments after birth, it includes images of a strand of Parke’s late mother’s hair, of his father’s wristwatch and of his children as they grow. Though very personal, some images appear coldly detached, particularly when the subject is captured under penetratingly bright light. One set of black and white images shows a sick child on a bed seen from high above; such a viewpoint creates a feeling of disconnection rather than empathy or sympathy. Some images are small, some overwhelmingly enlarged, so the viewer’s response shifts from observation to confrontation. The juxtaposition of images is also crucial, for example an image of tadpoles is placed next to that of a child as if to question their equivalence. While such images are loaded with symbolic and emotional significance, you get the feeling that the act of photographing a subject can defeat as well as convey personal attachment and sentiment.

The exhibition has been seven years in the making and began when a stranger offered Parke a cutting of what he described as “a black rose” and encouraged him to plant it, which he did in 2007. (The plant in Parke’s photo doesn’t look like a rose, but resembles an aeonium manriqueorum zwartkop, a species of subtropical succulent. The zwartkop variety is very dark purple, almost black.) In a voice recording, Parke speaks of the day in 2011 when the pot containing the black rose inexplicably fell and shattered while he was playing backyard cricket with his son. Naturally he photographed the broken pot and its spilled contents but there is more to the image than the triggering of his photo-journalistic reflex—coincidences and unexplained events are central to the artist’s thinking.

Fever, Dash Adelaide, 2014

© Trent Parke/Magnum Photos

Fever, Dash Adelaide, 2014

You can buy a lavish catalogue that includes Parke’s writing selected from 14 of his previously published artist’s books, the sources of some of the images in this exhibition. He talks of the death of his mother when he was 12, how for a time he blocked out the memory of her and how this prompted a series of works in which he reconsidered his childhood, his burgeoning interest in photography and photographic trips around Australia. The exhibition is set out as a personal retrospective whose elements are stitched into a narrative, a journey of memory, imagination and dreams like a story told in cryptic vignettes.

Trent Parke is a member of Magnum, the elite group of photographers founded by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa and others in 1947 as an agency for photojournalism and photographic art. His work ranges across the use of the photo as factual record and as fictional or abstract construct. There are images of people which have been so manipulated that the figure is a haze of dots, appearing as a ghostly, unrecognisable silhouette in a lighter ground. Occupying three sides of a room is a video close-up of the skin of a dying, decaying squid, an image that looks like liquid slowly bubbling and which is incomprehensible until explained.

There’s a set of 365 colour photos of the sun setting daily at the beach near Parke’s Adelaide home. This suite, covering one wall, examines the sunset as a visual phenomenon and signifies the photographer’s dedication to maintaining an observational record over an extended period. It becomes a metaphor for the rhythm of life; evidently he emailed each image daily to Magnum colleagues. These images are mounted as a single work that superficially resembles a strip of movie film that would collapse a year into an instant. This distortion of time is a recurring theme in the exhibition. But to gain the sensation of the sublime that a sunset can evoke, we must ignore the whole and study each image separately. We’re not only reminded of the adage that a photo is a moment frozen in time, but that we must appreciate each work in this exhibition, each moment, individually.

In another room, themed Outback, Parke shows a sequence of images taken at night in which the only source of illumination is his flash-gun; in a voiceover, he tells of scaring away a charging crocodile with the flash, the camera becoming a defensive weapon. Opposite these is a display of sensationalistic headlines from the Northern Territory News reporting crocodile attacks. Then there are images of death —cattle carcasses in the desert, a beached whale. There are shots of rabbits and a booted foot crushing a cane toad.

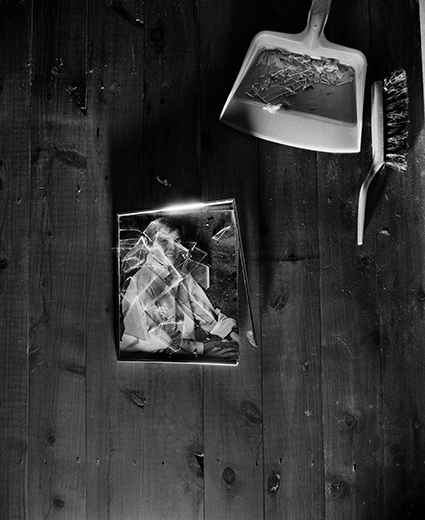

Trent Parke, Shattered portrait, Newcastle, 2009

Trent Parke/Magnum Photos

Trent Parke, Shattered portrait, Newcastle, 2009

Further on are Black Rose Tarot Cards, images chosen to symbolise characters or transitional states, alluding to Parke’s interest in fortune telling and mysticism and acknowledging his mother’s interest in Tarot. Lastly, again illuminated by his flash, there is a ceiling-high photo of a gum tree, which his mother years before had saved from destruction by developers. In creating this image, Parke felt he had concluded his journey.

The last room of the exhibition contains hundreds of rolls of developed film, hung like a curtain against bright light for our inspection, representing not only the vastness of his oeuvre but Parke’s commitment to continuous observation. Evidently he shoots a thousand rolls of film a year. The advertising for the exhibition shows an image of a bare-chested Parke examining processed film at the beach on Fraser Island in 2003, a romantic evocation of the young, visionary artist at work. The image, by Narelle Autio, has the flavour of an un-posed, spontaneous, Magnum-style shot. Several of her photos pepper the exhibition and she assisted in its development.

Trent Parke apprehends his world through the camera lens. The Black Rose can be seen both as autobiography and as an exploration of the use of photography to record events, convey memories, construct or represent ideas and create both optical and emotional effects. In weaving seven years’ work into an overarching narrative Parke seems to be trying to reclaim, or prove the veracity of, his own experiences. An abridged version of the exhibition may have captured the essentials of his approach to photography as an art and hence been more navigable for the viewer, but presumably would have omitted what for Trent Parke are important elements in his story.

Adelaide Festival, Trent Parke, The Black Rose, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 14 March–10 May

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 4-5