From under the skin

Julie-Anne Long: Dean Walsh, Flesh: Memo

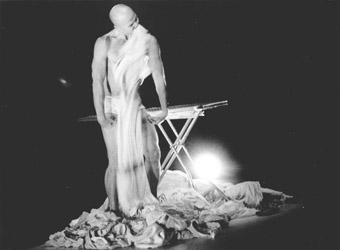

Dean Walsh, FleshMemo

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh, FleshMemo

Dean Walsh is a sublime mover who’s not afraid to open his mouth; a dance artist with an impressive physicality and a provocative way with words. Moments from some of his past works—Toffee Apple (1994), Testos/Terrain (1997), Retro Muscle Song (1999) and Subtle Jetlag (2000)—resonated for me in this latest work Flesh: Memo. The stilettos are gone but the memories linger on.

Flesh: Memo is in 2 parts, the first (unspeakABLE: acts) dealing with the Father, the second with Mother. As the audience enters Dean Walsh dances in a shadowy corner, grooving in headphones, his movement loose then tightly coiled. We admire his naked torso and, at the same time, read the inner conflict written all over him, crawling under his skin. Walsh rants and raves, whispers and confides his memories of family, father, step-father, of unspeakable acts of sexual violence. At times grim and depressing, the story is also unabashedly personal and often moving. Walsh makes effortless transitions in performance style and energy. His relationship with his audience shifts as he moves from displays of feline ease, precision and speed to macho posturing and aggressive face to face outbursts. There is a terrific whispering sequence performed with a whistle in his mouth, a finely honed ‘fighting moves’ physical phrase and some startling leaps between pain and humour. (I note that Andrew Morrish is listed in the credits and wonder how much, if any, is improvised.)

A lip-synched rendition of Cat Stevens’ Morning has Broken (a Walsh family favourite) sees Dean swinging from the balcony. This echoes a scene I’d witnessed earlier in the evening at the opening of the Cerebellum exhibition at Performance Space: the incredible Leigh Bowery in a Charles Atlas film Teach, lip-synching Aretha Franklin’s Take a Look, with a pair of pouting plastic lips safety pinned to his cheeks.

Simon Wise’s lighting design conquers the bleakness of the concrete brick walls and gloomy performance pit of the Seymour Centre, subtly illuminating flesh against grim surroundings (a floor strewn with nails, a steel ladder, an ominous empty chair)—all in keeping with the dark memories being reworked. New media artist Rolando Ramos provides a landscape of domestic detail projected on floor, screen and wall. I’m caught between enjoying the video’s texture, colour and line and frustration at its lack of definition.

The second act, Maternal Tattoo opens with a soft, kinaesthetically languid floor sequence. This time Drew Crawford’s hypnotic score embraces and supports Walsh’s fluid limbs. Using Butoh-based physicality and evocative gestural language, Walsh again wears this story on his flesh for all to see. He sure knows how to play this audience.

Some of the most powerful moments occur in the final 10 minutes. As he pegs a load of dripping washing to a line crossing the space, Walsh tells us a story about Saturday afternoons when “all the violent men were out of the house” and the boy and his mother would turn the stereo up full blast and sing their hearts out. Wearing a sodden petticoat and lip-synching to I just don’t know what to do with myself, the dancer moves from a puddle on the floor, slipping, reaching out, into a beautifully articulated balletic sequence, finally dancing to an aria from Glück’s Orphée—a mesmerising body in motion, intensely self-absorbed but without narcissism.

Flesh: Memo, Sydney 2002 Gay Games with One Extra Dance, choreographed/written/performed by Dean Walsh; dramaturgy David Sheridan, Nikki Heywood; lighting Simon Wise; music Drew Crawford; new media Rolando Ramos; Downstairs Seymour Centre, Sydney, Nov 30-Dec 8

RealTime issue #52 Dec-Jan 2002 pg. 23