gran turismo

nigel helyer does venice, basel, kassel, münster & paris

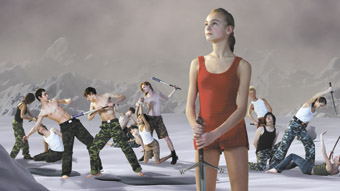

AES+F group, The Last Riot, Russian Pavilion Biennale of Venice

AS IN A FAIRYTALE, ONCE EVERY TEN YEARS THE STARS ALIGN IN EUROPA AND WITHIN A SPACE OF TWO WEEKS A SERIES OF MASSIVE EXHIBITIONS DRAWS HUGE CROWDS OF AFICIONADOS. THIS YEAR THE SPECTACLE WAS SPUN INTO A GRAND TOUR WITH THE CULTURAL EQUIVALENT OF SOCCER TRAINS LINKING VENICE, BASEL, KASSEL AND MÜNSTER INTO A PORTABLE VISUAL FEAST. BUT BEYOND THE BABBLE OF ARTSPEAK IN THE EXPRESS TRAIN DINING CARS, NO OVERARCHING CONCEPTUAL THEMATIC COULD POSSIBLY UNIFY THIS EXCESS OF CREATIVITY, UNLESS IT IS A TALE OF THE POWER OF THE MARKETPLACE.

venice, beuys & barney

Ah Venice! where the streets are paved with aqua, where advertising exclusively promotes cultural events (don’t they buy mobile phones or white-goods?) and where Australian taxpayer dollars could be seen in the form of fluorescent yellow show-bags, spreading like a cholera epidemic throughout the city (well at least for the preview days).

Elite and elitist, those Janus-faced words! In Australian parlance the word “elite” is proudly applied to sportspeople and the more dangerous elements of the armed forces. The word “elitist”, however, is reserved as a term of derision applied to the upper echelons of the art world, to serious intellectuals and occasionally to the filthy rich. As a rule of thumb it is not desirable to be one of the elite in this context (although the very wealthy are unlikely to take any heed).

The Joseph Beuys and Mathew Barney exhibition at the Peggy Guggenheim gallery, proved to be the pre-opening gala event of Venice. The Italian door bitches proved to be no push-over for the naively un-ticketed, like me, so gaining access to the event required a combination of charm, persistence and psychology.

The B+B exhibition was ploddingly curated as a series of back-to-back displays; a Beuys drawing mirroring a Barney drawing, a Beuys video facing off a Barney video and, of course, Beuys Fat and Barney Fat smeared alongside one another in what seemed a concussively unsubtle attempt at transubstantiation. The spirit of Beuys decanted into the veins of Barney; an undisguised act of deification; or simply smart market re-badging?

Naturally there are parallels between the two artists, each equally possessed of an Asperger-like obsession with ‘self’ coupled with a savvy ‘showman’ persona, eager to manipulate the media. But how do B+B fit into the elite and elitist schema?

As it turns out both could claim to be elite from a sporting perspective, each incorporating physical challenge as part of their creative practice. Barney for instance amalgamates abseiling with mark making and his semi-athletic, semi-balletic performances that have seen him scale the ramparts of the NYC Guggenheim (see page 10 for Barney’s performance in Il Tempo del Destino).

Beuys with typical Germanic pragmatism went in for noses bloodied in boxing matches for Direct Democracy, and how can one be an elitist with a bleeding snout?

Recall the image of Beuys cradling a dead hare, engaged in a deep discussion about contemporary art, claiming that despite being deceased, the hare would have a better natural comprehension that an elitist academic or art critic.

This is the time to reveal the skeleton in my cupboard—I must confess to being a Beuys Scout as a young and earnest art student, even meeting him on a couple of occasions, which only amplified my total awe of his practice and its ethic of RealPolitik but, equally so, of his persona. Beuys was amongst the vanguard of artists who re-established a European cultural agenda, reclaiming it from the thrall of (CIA backed) American abstract art that had dominated museums on the continent throughout the 1960s. One can only suppose that the Guggenheim’s B&B voodoo is an insidious form of neo-colonialism now operating as a globalised cultural industry.

What is conveniently forgotten in the Guggenheim’s attempted transaction is that despite being a mercurial shape shifter, Beuys held a passion for social democracy, for a cultural openness and for art that operated simultaneously in the mundane world and at a deeper spiritual level. This attempt to bring into close association the saintly relics of Beuys (now entirely dissociated from his cultural politics) with the Hollywood scale indulgences of Mathew Barney, illustrates how dumb the übermench of the art world can be, or at least how dumb they think we all are.

venice: in the pavilions

La Russie, Douze points…La France, Dix points…La Mexique, Huit points…

There is a certain irony in the faux cultural identity associated with the individual national pavilions when placed in the context of a powerfully globalised (or at least internationalised) cultural economy. Interestingly enough the coalition of the willing offered rather thin pickings at Venice, whilst in true EuroVision style the non-aligned nations delivered.

Douze points: inside the Russian Pavilion, Wagner’s Flying Dutchman announced an animated, post-apocalyptic cyber-epic, The Last Riot (AES+F group), in which androgynously beautiful but heavily armed teenagers suggest the dissolution of collective Utopias under the fracturing pressure of Global Capital.

The dystopia of The Last Riot was sharply contrasted by the Kabakov’s beautiful installation at the Arsenale where a model utopian city recouped the visionary architecture of 1920s Soviet culture, an interesting foil to the generation currently witnessing the economic chaos and ideological vacuum of a Russia unbound and directionless.

Dix Points: the French Pavilion housed a massive and sophisticated project by Sophie Calle. Unlike many grandstand attempts at Venice, Calle never de-rails into the trite or formulaic (as is the fate of so much successful art!). She is possessed of an emotional focus and obsessive attention to detail that allows her to take a simple, but emotionally charged text (in this case an email) and submit it to a process of collective inquisition that she subsequently manages and produces as a communal response. The result is a combination of Calle’s own creative agenda but also an embrace (and confidence in) a plural voice. The role of ego here is sublimated into one of social responsibility.

Huit Points: some of the most interesting exhibitions in Venice kept away from the zoo of the Giardini and the Arsenale, preferring to be tucked away in elegantly decaying palazzos. The Mexican Pavilion housed a series of mature and engaging interactive works by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer which stood out as some of the only interactive new media works in what was otherwise a very conservative curatorial vision of contemporary practice, and because they functioned at a strongly visceral level.

Hemmer’s Pulse Room contains a lectern-like object sporting two hand-held sensors. At eye level is a single low wattage filament lamp. Each participant stands for a few seconds breathing calmly while staring at the lamp which soon begins to pulse with the heart-beat of the visitor. A friendly attendant then ‘migrates’ the pulse into the ceiling space that supports hundreds of identical lamps, each twinkling with the heart-beats of previous visitors. It is not often that such simple technology can have such an emotional effect, but Pulse Room gives each participant the gift of ascension into a temporary communal heaven.

L’Australie…Daniel von Sturmer’s attempt to transform Cox’s beach-house into a plausible exhibition space functioned well enough in an architectonic way, with its Ikea-smooth mobius strip of plywood snaking through the space; the inclusion of video vignettes on this support was however unproductive and underwhelming.

video hell

I’m beginning to think that the ubiquitous and seemingly mandatory presence of video in art festivals is a conspiratorial form of low-level torture, as yet unrecognised by human rights groups. In this context video consistently fails to adequately differentiate itself from familiar televisual and cinematic formats and formulae. In the rare case that video makes a substantial claim to otherness (say Viola or Ousler) they still short circuit the process of contemplation.

From the perspective of a card-carrying videophobe there are two factors that combine to undermine videographic practice as a truly engaging medium rather than one that primarily signals an economy of informatics and infotainment. The Pavlovian training that most people receive in screen-culture from early childhood generates a deeply ingrained response to video; in McLuhan’s words, The Medium is the Message (or was it Massage?); by adulthood, content is hardly the issue, the format itself is hypnotic.

Notwithstanding the above, the fundamental modality by which we engage with architectural space and sculptural form is radically different and essentially incommensurate with the manner of engaging with the video screen. The former demands a dynamic, spatial engagement that draws upon kinaesthetic and haptic processing, while the latter demands an unblinking, static focus; there are scant examples of work that accomplish a fusion of these modalities.

Ciao Venezia — and so onto the Express Train for an encounter with market forces!

basel bypass

Art fairs are of course, not to be taken seriously—that would plunge one into terminal despair! They are however extremely instructive in the fickle ways of the marketplace and its grip on many aspects of creative production. Adopting the morphology of an Easter show mixed with a rambling American art school graduation exhibition, the Basel Art Fair was all booths, business cards and cash-flow.

The essence of the Basel Fair is ironically exemplified by a work which was not on show but which was on the tip of every dealer’s tongue—Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God, a human skull in platinum and encrusted with 8,601 diamonds, conservatively priced at US $100 million. The terms of Hirst’s Mephistophelean contract are such that while it offers him unlimited fiscal success it progressively robs him of the capacity to be meaningful, stripping him even of irony.

Susan Philipsz, The Lost Reflection, Munster Skulptur Projekt

photo Roman Mensing

Susan Philipsz, The Lost Reflection, Munster Skulptur Projekt

kassel and münster

A tale of two cities: both pounded into oblivion by the close of WWII due to their enthusiasm for Kristallnacht and their capacity to produce panzers. Kassel rebuilt in a hurried Sovietesque reconstruction style, all concrete and rectilinear; Münster choosing a Disneyland simulacra of its medieval past, but both cities adopting art as the focus for their long-term rehabilitation.

As a city venue Kassel has visibly matured over the past decade, the pizza bars and ice-cream parlours now replaced by a host of good restaurants. The city boasts some wonderful open spaces and fantastic public transport; less can be said for Documenta itself, however, which over the past two incarnations has lost the plot. In 1997 the combined Documenta and Innenseit exhibitions pumped the city’s architectural and public spaces full of ambitious, high production value projects, setting a benchmark that the subsequent festival in 2003 failed to match in its rather literal translation of Documenta into documents and documentaries! The current offering is totally anaemic by comparison, the curatorial team pouring energy into devising a typically Germanic polemic schema that they subsequently find impossible to embody in practical terms. The result is a rather perplexing assortment of non-sequiturs stranded in a matrix of curatorial idiosyncracies: irrelevant colour schemes, silly curtains, very low lighting and a penchant for hanging as many large Juan Davila paintings as possible at each of the festival venues, much to the horror of many European critics who found them gauche and ugly, and who am I to disagree? Davila once named a painting As Stupid as a Painter; after Documenta 2007 we could maybe stretch this to As Conceited as a Curator!

The good thing about the Skulptur Projekte Münster is that it is an outdoor event best seen from the saddle of a bicycle so even if the art is crap one cannot avoid having a pleasant time zooming around the cobbled streets and old city ramparts. At its best the work in Münster engages with the architectural and historical fabric of the city in a critically reflexive manner which was certainly the case for the last incarnation in 1997. Again however, the German curatorial team fumbled the ball, delivering the current festival with fewer than half the works shown last time and most of these less directly engaged with an articulation of the urban cultural fabric. Many of the best works are however retained in the city, accumulating as a permanent sculpture park.

One exemplary project is a site specific installation by Rebecca Horn that places small mechanical hammers inside an old fortified tower, once used by the Nazis as a meeting place and by the SS as a torture chamber. The hammers are slowly and quietly chipping away at the decaying walls of the bastion and ipso facto into the difficult history of the Fatherland. Ten years ago this project was flanked by an equally impressive work by Hans Haacke. Morphologically similar to the tower, it took the form of a vertical cylinder built from scaffold planks that contained a fairground carousel. Squinting between the planks one could just see the painted horses merrily dancing by to the fair-ground organ refrain of “Deutschland Über Alles.” Further along the promenade is a German war memorial, once again in the shape of a turret, resonating with both projects.

This year it was hard not to be amused by Mike Kelly’s animal Petting Zoo, we are all suckers for donkeys after all. One could be charmed by Lost Reflections, Suzan Philipsz’ haunting sonic installation in which the barcarole from Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann drifted across the lake, or engaged by the humanist discussions in the marquee that housed Beautiful City, a social sculpture produced by Maria Park. However the perception by many visitors that the level of ambition and quality are declining makes me nervous.

kiefer in paris

Back on the train to Paris to see Anselm Kiefer’s Falling Stars, the first work in the aptly named Monumenta series at Paris’ Grand Palais. In German, Kiefer may be referred to as a ‘Malerfürst’, a term that compresses painter with duke and this is more than appropriate when regarding his Rabelaisian scale exhibition at the Grande Palais. The Palais contains a series of shattered concrete towers, entwined with iron forged sunflowers as well as a series of hangars, containing arrays of massive paintings, reliefs and free standing sculptures. A tour de force, speaking not only of the creative impulse, but flaunting the sheer economic power that the artist commands.

It is the issue of scale, in a variety of guises that strikes a chord. In the first instance the very concept of hosting a solo exhibition in a structure designed to house entire nineteenth century international trade fairs proposes an eccentric vision of how art operates, anachronistically valorising heroic actions and epic forms.

From a personal perspective Kiefer’s work contains interesting scalar contradictions in that the conceptual source is frequently of an intimate and indeed scale-less nature, for example an extract from a poem or text such as Voyage au bout de la nuit by Céline, but which is then manifest at Wagnerian proportions in a surfeit of production.

The second scalar transformation concerns the artist’s touch. Kiefer’s oeuvre is, above all else, tactile and organic, bearing the mark of the skilful hand. At the same time it is not only heroic in physical scale but also appears to multiply in a serial, one might say industrial, scale production. The modest Kiefer show at the AGNSW recently was in fact a small clone of the gargantuan Paris exhibition, palm tree and all. The touch of the hand is therefore deceptive, and may well not be Kiefer’s!

Anselm Kiefer has perhaps mastered the art of eating his cake and keeping it too! Although I’m pretty sure that he is obliged to share it around with the army of elves that he obviously retains in the underground tunnels of his studio in France. I like to imagine him spending time each evening before he retires, laying out the snacks for his willing helpers.

52nd Biennale of Venice, June 10-Sept 5; Basel Art Fair, June 12-17; Documenta 12, Kassel, June 6-Sept 23; Skulptur Projekte Münster 07, Sept 22-30; Monumenta 2007, Anselm Kiefer, Falling Stars, Grand Palais, Paris, opened May 30

See page 25 for Zanny Begg’s report on Hito Steyerl’s Documenta screenings

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. 2,3