Grimmer childhood aesthetics

Bryoni Trezise: Chiara Guidi, Jack and the Beanstalk

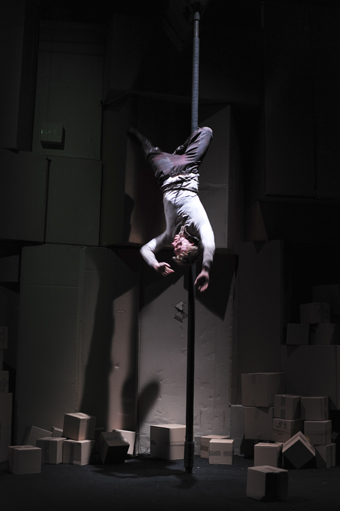

Drew Fairley, Skye Gellmann, Jack and the Beanstalk

photo Heidrun Löhr

Drew Fairley, Skye Gellmann, Jack and the Beanstalk

A new aesthetics of childhood is emerging with some of the key contemporary performance companies of the last decade. Mammalian Diving Reflex’s ground-breaking Haircuts by Children contemplated the agency of children and the vanity of adults by reversing the conventional power dynamics of the hair salon. Italy’s Compania TPO’s multimedia works enfold children in the interactive, reactive environments of collective story-building, and stalwarts of the postmodern stage Forced Entertainment have just announced their first work for children: The Impossible Possible House.

In Australia, My Darling Patricia recently applied their signature cross-artform aesthetics to the visually immersive The Piper for the 2014 Sydney Festival. And alongside designated festivals for children (Come Out and Out of the Box) and spaces for child creativity (Melbourne’s ArtPlay), there is a genre of works for babies emerging with dance artist Sally Chance’s This Baby Life and Nursery.

These creative frames inevitably contemplate the cultural figuring of the child as a symbol of purity, morality and nascent humanity in the contemporary media landscape. They also recognise and become entangled with the truism that seems to come with societies of affluence: child audiences are a fickle and yet lucrative market. In a broader socio-political context which has witnessed seismic reconsiderations of the legal and moral agency of the child, as in Belgium’s recent legalisation of euthanasia for terminally ill children, the question of how these varying theatre practices interpret the imaginative and perceptual faculties of children is perhaps at the heart of this vibrant artistic milieu.

Jack and the Beanstalk, the final iteration of a three-part collaboration between Chiara Guidi of Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio and Sydney-based performance makerJeff Stein in partnership with Campbelltown Arts Centre is, if not a frontrunner, then an originator of this scene. Guidi’s Experimental Theatre for Children based in Italy has been operating since the 1990s and in 2010 she ran The Art of Play, a cultural exchange at Campbelltown, during which she spoke at length about her vision for the sympatico aesthetic between the worlds of childhood and theatre: both are equally invested in the reality-effects of make believe [RT100]. In 2012, Guidi returned to develop Jack [RT108] and in 2014, she came back to complete it.

Skye Gellmann, Jack and the Beanstalk

photo Heidrun Löhr

Skye Gellmann, Jack and the Beanstalk

Jack and the Beanstalk begins with a foreboding stillness. Jack and his mother appear to lie dead under a box while a strangely masked figure draws an ominous circle around them. The sonic environment is already sparse and stretching, the lighting dim, the mood dark and hesitant. From the outset this image is not easily readable: the familiar lightness of contemporary fairy tales is undone with an image that hangs like an uneasy promise over the whole work: do they die in this version? Then Jack moves, and the process of barter between beans and cow begins.

We understand that Jack is poor, his mother bids him to sell the cow and in an athletic exchange between Jack, his mother and the bean seller, Jack’s wrestle between conscience and desire is made tangible. His mother, of course, is furious and berates him for ‘dreaming.’ The audience, holding handfuls of beans, are encouraged to throw the beans “against Jack’s dream:” there is no supper for Jack tonight. This interactivity with the audience introduces a dynamic that is expertly built across the work, conducted by the deviously masked Katia Molino as the ogre’s ‘handler,’ who is neither friend to Jack nor the audience, betraying both at every turn.

Guidi spoke in a recent RealTime video interview of her interest in the fable for its spatial metaphors: the beanstalk draws a line between heaven and earth, dream and reality and the beans are much like theatre itself: a box from which magic unfolds. She also referred to Jack’s negotiations with the giant as a series of initiations into adulthood. Perhaps the fable can be read as a coming of age narrative in which we all learn an ambiguous moral lesson. Jack is a kind of illegitimate protagonist, he steals from someone without cause, and as an audience we are left to wrestle with our own responses to his acts of dreaming and desire.

If our consciences are pricked on behalf of Jack’s actions, then so are our senses. Building on her earlier experiments with chorality and space [RT90], Guidi also referenced her use of sound as a visual and structural device. Live musicians in the work (Trevor Brown, Veren Grigorov) play Max Lyandvert’s sparse, staccato and at times thunderous composition, but Guidi here also refers to the musicality of her pared back dramaturgy: tight physical sets and truncated dialogues apparently aim to access the ‘core’ of the fable, leaving nothing to waste.

Jack and the Beanstalk

photo Heidrun Löhr

Jack and the Beanstalk

The world Jack dreams is an incredible cardboard structure (created by Sydney’s Erth) that stretches to the skies as a series of hidden doors and windows. Objects exit and enter from these sinister little peepholes. At various stages spectators become bold enough to visit the giant who lives above; in their absence, the cardboard machine spits out remnants of story—a box with letters, a human skull and bones. Strange slinky worm creatures flop and poke about the stage. The children barter with the handler, collecting the giant’s discarded debris, becoming willing victims to his voracious appetite. While the golden goose majestically appears as an image of sensitive wonder amid the darkness, it is not long before the ogre himself manifests as a chilling apparition shrieking the kind of blackness you just might find in nightmares.

How to justify the death of children, the greed of children, their bravery, sensitivity, complicity and fearlessness? The work is macabre, it feels, in the historical tradition and conditions in which fairytales themselves once needed to be imagined. Perhaps it carries that historical necessity cuttingly into the present. Throughout, we are required to contemplate the prospect of a world in which the child is not always a winner, or even right. The children in the room, for one, seem unnervingly content with this bleak but complex image of themselves.

Campbelltown Arts Centre, Jack and the Beanstalk, director, writer Chiara Guidi, facilitator, producer Jeff Stein, performers Skye Gellmann, Katia Molino, Drew Fairley, Christa Hughes, Nadia Cusimano, musicians Trevor Brown, Veren Grigorov, sound design Max Lyandvert, set design Erth Visual and Physical (Scott Wright, Steve Howarth), Lighting Clytie Smith, Mark Haslam; Campbelltown Arts Centre, NSW, 30 May-7 June

RealTime issue #122 Aug-Sept 2014 pg. 42