harmony between man, earth, heaven

zsuzsanna soboslay: canberra international festival of chamber music

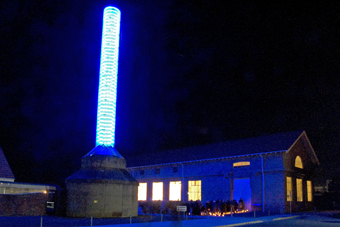

The Fitter’s Workshop

photo Peter Hislop

The Fitter’s Workshop

WALTER BURLEY GRIFFIN, THE ARCHITECT OF CANBERRA, ONCE WROTE THAT “A CITY IS FROZEN MUSIC.” ACCORDINGLY CHRIS LATHAM, THE DIRECTOR OF THE RECENT CANBERRA INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF CHAMBER MUSIC, REFLECTED THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MUSIC, ARCHITECTURE AND THE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE HUMAN BODY IN A FESTIVAL EXPLORING DIFFERENT SPACES FOR PERFORMANCE AND DIFFERENT WAYS BODIES RECEIVE AND UNDERSTAND SOUND.

From Domenico de Clario’s all night piano vigil to a full performance of the Monteverdi Vespers, Latham placed concerts in venues ranging from the soaring atrium of the High Court to the angular, postmodernist foyer of the National Museum, to the low, sleek, domestic interior of the Swiss Embassy, a 1970s New Brutalist reverie in concrete and glass.

In this last venue, Swiss oboist Thomas Indermuhle illustrated the contiguity of these ideas on an intimate scale, showing how tonguing, rasping, buzzing, tapping and singing into the bore of the instrument can create a performance alchemy that makes wood sound like metal and the performance “feel quite vocal” to the performer.

Cordiality between performer and audience occurred even in the most vast of spaces, belying the fact that the majority of the 10 days of concerts were of unashamedly ‘high’ ambition and tone. The festival opened with the New Purple Forbidden City Orchestra—”China’s finest ensemble of traditional instruments”—with music “from the great dynasties of Chinese history” and poetry from the I Ching. These ancient ritual traditions unashamedly revere music as go-between of cosmic and material worlds. The nearly 30 concerts which followed honoured these aspirations in a series of prayers, praises and laments, trances, motets and incantations, the composer list—from Josquin, Aquinas, Bingen and Gesualdo to Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, Mahler, Messiaen and Takemitsu—reading like a who’s who of classical and pre-classical ‘greats’.

Of the living composers (for example, Ross Edwards, Sofia Gubaidulina, Rautavaara, Gorecki, Tavener, Sculthorpe), most aspire to a tone of epic reverence, with some (Sculthorpe and Edwards of course) also paying homage to landscape and western and indigenous histories. The sole minimalist on the program, Terry Riley, builds his work based on pitches and rhythms from ancient Indian traditions. His peers treat his work and the man himself as an inspiration and kind of saint.

If I have any lingering doubts about the festival, it would be the way its offerings resisted dark spaces. Even that Australian master of the macabre and the Grand Guignol, Larry Sitsky, was represented in more moderate incarnations, whilst Elena Kats-Chernin, her Motet wedged between several powerful, trance-inducing choral works by Arvo Part, played lightly on the edge of satire.

The festival’s ‘Gold’ theme reflects Latham’s focus on things precious, from water to gemstones to unguents such as frankincense and myrrh. Various rituals were at least referred to, if not performed: journeys towards marriage, to the underworld, to allaying death, or of the Magi. Some epic feats were achieved: from Mahler to Strauss and Wagner to Tavener within two days, under the baton of Roland Peelman, for the most part to very good effect and sometimes stunningly. Perhaps by focusing on ritual and beauty the festival asked its audience to focus its ears in very particular ways.

It was a canny move to program the Australian Baroque Brass to play and repeat its offerings in different spaces so that the audience could pay attention to variations in acoustics. A contemporary audience, already a little distanced from familiarity with the sounds of sackbut (literally “push-pull”—a predecessor to the contemporary trombone) and cornet brought curious ears to the short performances which, like a progressive dinner, moved from one type and size of building to another. We were treated to a kind of attunement, not just to what, but also to how we hear and give shape to interpretation.

Jouissance, Kassia

photo courtesy of CIMF

Jouissance, Kassia

The Melbourne group Jouissance is exemplary in this aspect. The group creates dialogue between ancient chant and contemporary culture. Here their focus was the medieval Kassia, considered the first female composer whose scores are both extant and able to be interpreted by modern scholars and musicians. The group interacts with, rather than replicates, early work. Artistic director Nick Tsiavos says that studying postmodern theory in the 1980s made him think hard about contexts—what era we live in, what our own ears and experiences bring to any interpretation. The result is a performance philosophy that sees historical interpretation transformed by contemporary zeitgeist.

Tsiavos’s double bass sometimes breaks with jazz-influenced riffs; Peter Neville’s playing of contemporary, conical ‘Ausbells’ and simple, hung pieces of sheet metal carry medieval resonance but allow a sassy exploration of contemporary mood. Anne Norman brings her generous, elastically expressive shakuhachi into the fold (this is Byzantium via Japan), whilst Jerzy Kozlowski’s canonical bass resonates to our more secular sorrows. Deborah Kayser’s soprano breaks and dives and flutters in an extraordinary free-form exploration of, and improvisation around, the emotions of the mystic Kassia’s text. At certain moments, I am quite sure Kayser’s body has become a shakuhachi, mimicking its tonalities and technique (tonguing, fluttering, and shaking). This body and voice become the temple of Kassia’s prayers.

Significantly, Jouissance’s primary modality is improvisation, which was not a key element in this festival. Because this group is so practised in the art, it achieved alchemical transformations, which I would not say was always the case in the themed concerts such as “In Praise of Water.” It moved from composed mantras interspersed with improvised reveries, to one of Copland’s aching prairie-calls, to a very moving, but traditional rendition of Waltzing Matilda in a curious sequence that almost came off. By his third improvised interlude, Bill Risby developed some very interesting reflections on the preceding musical themes, yet I sat within an experience that felt thematically controlled, not musically released.

The standout in this very concert, however, by the festival’s resident composer, tells a different story. Ross Edwards’ The Lost Man (words by Judith Wright) is a delicate and demanding piece that sets up layers of listening in slow waves that build and recede and build again throughout. Edwards manages to gesture to the qualities and motions of water without pretending to make it. The piece harvested the piano; I heard it fill like a precious lake. Edwards writes about his compositional process as “an interplay of (materials) assimilated and interfused with sound patterns subconsciously gleaned from the natural world.” This suggests that for all his ideas, research and technique the composer allows something else to take over, relinquishing control.

It was good fortune the festival secured the Fitter’s Workshop, part of the 1920s Powerhouse Precinct in Kingston on the Lake foreshores of South Canberra—an enormous but welcoming, clear and fresh space of bright acoustic which many Canberrans hope to co-opt as a permanent performance venue. It was also exceptionally canny of Chris Latham to weave together the combined forces of amateur, professional and student choirs and orchestras—including the T’ang and New Zealand String Quartets, the Song Company, the Canberra Camerata, the forces of the School of Music, ANU—and other local professionals and composers, to weave a strong sense of support and community. The festival’s resources were bolstered by each concert having a personal sponsor from within the local community.

Much of the success of these concerts was due to the extraordinary abilities of Roland Peelman who could elicit both subtle and impassioned musical nuances from the professional and amateur instrumentalists, soloists and choirs, and somehow blend the voices. The grand finale of the Vespers, written in 1610, called for precise coordination between melismatic vocal lines and ostinato (provided by lute, contrabass and cello] and fine judgment in moving between different, complex groupings of voices, especially when in canon. The great unison “Amen” charged the room, as if the Age of Doubt, which began three centuries after its composition, never really happened.

In some concerts, but not most, one could feel the strain of attempting too much. Yet at their best, the combined forces achieved a translucent dignity—perhaps too the goal stated in Hexagram 16 of the I Ching: “harmony between Man, Earth and Heaven…a dance of Man with the Stars”.

Canberra International Festival of Chamber Music, May 14-23; www.cimf.org.au

RealTime issue #97 June-July 2010 pg. web