Highly charged connections: Visual arts, RealTime 1994-2004, Part 1

This is Part 1 of a two-part look at RealTime’s visual arts coverage. Read Part 2 here.

As Assistant Editor this year for RealTime, I’ve had the enviable role of sifting through all 64 editions from the magazine’s first decade in order to survey visual arts coverage during this period. While RealTime is perhaps best known for its documentation of experimental performance and media arts, I found such an abundance of visual arts material that one of my biggest challenges was deciding which pieces to highlight in an overwhelmingly erudite and thought-provoking collection.

My own relationship to RealTime, and to visual arts, is a close one. I’ve proofread the magazine since 2010, started reviewing films for it shortly after and joined the in-house staff in 2012 as Advertising Sales Manager. As a reader, I first picked up a copy at a dance studio in the early 2000s. Before that, in the late 90s, I was a fine arts student at COFA (now UNSW Art and Design), a member of the generation of young artists that figures in RealTime’s often bleak coverage of the impact of economic rationalism on tertiary visual arts education and artist-run spaces in Australia at that time.

Being propelled through these articles back to the world of a younger self was disorienting yet illuminating; seeing the period encapsulated and analysed here gave a wider context to personal memories. Something that struck me particularly was how RealTime’s first decade coincided with a period of transformation in the arts: technically, with the rapid onset of digital technologies, politically, with economic rationalism, and culturally, with Indigenous and Asian-Australian artists gaining prominence.

In Part 1 of my two-part overview of the decade 1994-2004, I look at coverage of the structures and institutions that facilitated new developments in contemporary art — tertiary education, the alternative gallery scene, state-funded festivals of contemporary art, and, in a wide-ranging historical overview by Djon Mundine, the Aboriginal art “industry.” I then move on to discuss other surveys of Indigenous art.

Interconnectivity & emergence

RealTime’s Managing Co-Editor Keith Gallasch has described Sydney’s contemporary arts scene during the 1990s as a golden age of interconnectivity between art forms. From the magazine’s inception in 1994, RealTime reflected and promulgated this sense of hybridity in a national context, enticing readers to traverse artforms rather than sticking to their primary interest areas. Amid the vast array of practices reviewed, the visual arts were no exception, with works and exhibitions typically complex, multilayered and resistant to categorisation.

A selection of artist interviews is illustrative: UK-based Crow, whose grunge installations encompass performance, text, photography and site-specific histories related to mental health [RT 17, p 35]; the elegant sculptural installations and public artworks of Robyn Backen, exploring technologies of vision [RT 24, p 41]; multimedia artist and lecturer Leigh Hobba, with a background in video art, sound, photography, drawing and collage [RT 33, p 29]; Indigenous artist Fiona Foley whose diverse practice includes community projects, public art, set design, and traditional batik and dying techniques [Living the red desert, RT 35, p 34]; and Ruark Lewis, with work ranging across installation, performance, text, sound, public art and collaborative projects [RT 38, p 33].

RealTime’s editors and writers sought out the places where ground was being broken across both old and new media; the sense of the experimental and untried emanating from emerging artists, including fine arts graduates, new cross-cultural conversations, multidisciplinary approaches, new media and the transformative potential of more traditional forms.

Bolstered by funding from the Australia Council’s newly formed New Media Arts Board from 1996 on, the cutting edge field that included digital art, hypertext, gaming, web and bio-art received an enormous amount of coverage from RealTime from its first edition to the NMAB’s dismantling in 2004 and thereafter. A forthcoming overview will address this significant field and its influence on other practices.

From the mid-90s onwards, RealTime was committed to covering the trajectory of the emerging artist and the sorts of spaces and conditions that formed ‘laboratories’ for experimental contemporary art. Articles explored tertiary fine arts education, graduate exhibitions and artist-run spaces and initiatives which were gaining currency in the 90s as venues for contemporary artists to kick-start their careers, while also offering a more liberating alternative to the private gallery system. The writers who focused on these issues were frequently visual artists themselves, sometimes also working as university lecturers, bringing to light in their coverage a sympathetic picture of the predicament of both art institutions and emerging artists.

Hard times for arts education

RealTime’s responses to the annual Hatched: Healthway National Graduate Show and Symposium at PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Art) reveals tertiary fine arts departments forced to perform a precarious balancing act following the newly elected Howard Government’s university funding cuts in 1996, between adopting an increasingly cautious managerial model and fostering risk-taking and adventurousness in new generations of contemporary artists. Dean Chan noted the negative impact of economic rationalism on the work produced by visual arts students in his report on Hatched 1997 [Panic (at) Hatched, RT 20, p 41], “when funding allocations more than ever before require qualification and quantification in terms of performance measurement criteria,” though a notable exception was a series of paintings of digitally manipulated imagery by SCA (Sydney College of the Arts) graduate Sean Gladwell.

The following year, in an article ominously titled “The brave and the brutalised,” [RT 26, p 11], Perth correspondent Sarah Miller puts the beleaguered state of visual arts education into context:

“…over the past decade, and particularly since the amalgamation of art schools into the university system, arts education (both creative and liberal) has been under increasing attack. Such attacks have been compounded by the restructuring (downsizing) of the university sector and the reintroduction of fees. It is argued that universities (including their poor art school cousins) have never suffered so much. They are ridiculed in the press, sneered at by politicians and dismissed by industry (the real world) and are under increasing pressure to perform in an economically rational climate (ie without any money).”

Despite these grim conditions, the 1998 Hatched exhibition and symposium leave Miller with a tentatively optimistic view on “the persistence and power of artmaking and the value – not simply fiscal – of an education in the arts.” In the same edition, her article is complemented by an eloquent overview by art and architectural lecturer at UWS, Philip Kent [Grading the making of art, RT 26, p 12], of the issues arising from the absorption of many art schools into Australian universities in the late 1980s – an initiative that had a clear impact on the way a new wave of fine arts graduates conceptualised the art they were making.

Jump ahead a couple of years to RealTime’s 2000 education feature, and artist and lecturer Barbara Bolt highlights the predicament of the “Art teacher as anxious manager,” [RT 38, p 12] in the lead-up to an ACUADS (Australian Council of Art and Design Schools) conference that year. The ACUADS newsletter prompts Bolt to analyse the use of corporatese in relation to visual arts education, and to consider its impact on lecturers and students alike:

“Like all university departments and faculties, art and design schools took on the language of managerialism in order to “get bums on seats,” to be accountable and satisfy the number crunchers. But has this effort led to greater self determination and leadership or to an increase in creative achievement and satisfaction? It seems not.”

Contrasting the “fearful anxiety” of art school administrations with the more positive “playful anxiety” required of art students, Bolt rallies art teachers to shake off “static and rigid representational concepts” that engender “fear and trembling.” She urges, “We should leap into the void and become chameleons for the day. Otherwise, what sort of leadership can art and design schools provide?”

The galleries: ARIs and alternatives

Subject too to the forces of surging neoliberalism were the artist-run spaces and alternative galleries that were often the first port of call for newly minted art school graduates, including Sydney’s First Draft, Hobart’s CAST (now CAT) and Adelaide’s CACSA (now closed). RealTime articles of the 90s and early 2000s chart the shifting fortunes of Australia’s vibrant alternative exhibition scene, providing a valuable snapshot of venues that prevail, and those that now exist only in documented form. A selection of Sydney-focused articles provides a good sense of the history. Jacqueline Millner begins a 1997 report on Sydney’s alternative gallery scene [New guard avant-garde: Sydney’s alternative gallery scene, RT 19, p 9] by noting the recent loss of spaces like Selenium, Airspace, Toast and Particle, before profiling the emergence of new ones. Of these galleries in their infancy, Gallery 4A (now 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art) still thrives, while 151 Regent St, Side-On Inc, Raw Nerve and Room 35 have fallen victim to the rising value of real estate.

In RT 23 [p 32], Millner visits First Draft’s last exhibition of 1997, at a perilous time when public funding for the 11-year-old gallery had been withdrawn. “Considering the vital role the gallery has played over the last 11 years to nurture a wide spectrum of emerging contemporary artists, this is very bad news for Sydney’s visual arts community,” writes Millner while noting that the incoming directors were determined to continue running First Draft, albeit with the added complications of having to secure sponsorship and raise exhibitors’ rents [The gallery survives to this day]. In an acute critique from 1998, Alex Gawronski examines the effects of neoliberalism and gentrification in the lead-up to the Olympics, on Sydney and Melbourne’s artist-run spaces as soaring rents forced gallery tenants out.

In an echo of the education article themes, Gawronski writes, “Beyond such prosaic issues lies evidence of a deeply rooted attitude to contemporary art at social and governmental levels. In certain ‘official’ contexts contemporary art is regarded with suspicion as a type of luxurious, irresponsible hobby, largely because of its apparent disregard for profit.”

He concludes, “Thankfully, artist-run spaces continue to emerge,” though this “is testimony more to the determination, commitment and faith of artists and gallery supporters than an informed cultural, social consciousness regarding contemporary art practice in Australia today.”

Post-Olympics, Gawronski returns to the alternative gallery theme to contrast two Sydney galleries exhibiting “distinctly hybrid tendencies,” but possessing markedly different management styles [Bridging the divide: gallery developments, RT 41, p 29]. Grey Matter, “located in the modest Glebe residence of its tenant, Ian Gerahty,” is a one-man operation, cosmopolitan in outlook (bringing in overseas as well as local artists); grassroots and exploratory in practice. Gallery 4A, five years on from Millner’s report on its early days, receives both corporate and Sydney City Council funding, offers art in exchange for patronage and fulfils an important role in promoting contemporary Asian art. Gawronski documents a moment when 4A was moving away from its smaller, communal beginnings towards a museum-like model. “The centre’s increasing success as a quasi-corporate entity has made its role vaguely ambiguous.”

Was the artist-run space/alternative gallery scene becoming too much a part of the system to generate truly experimental work? In 2001 Gawronski considers the suggestion, floated at a forum on artist-run spaces, that such venues have lost their radical potential and now merely mimic the commercial model [The outsider gallery, RT 45, p 26-27]. He presents a handful of alternatives that deliberately confound conventional exhibition structures, including the Glovebox series of temporary carpark exhibitions and Squatspace on Sydney’s Broadway. “Such efforts promise to render the exchange between artist, gallery and public venue and community more fluid and, at the same time, less definable.”

Bigger pictures: contemporary art festivals

As well as following the fortunes of small, grassroots projects and spaces, RealTime devoted significant attention to major festivals of contemporary art. Under the incisive visual arts editorship of Jacqueline Millner, the magazine ran features in partnership with Australian Perspecta, the NSW-based biennial festival of contemporary Australian art that ran from 1981-1999. RealTime writers tackled the grandiose themes of Perspecta 1997: Between Art and Nature [RT 20, p2-6], and Perspecta 1999: Living Here Now: Art and Politics [RT 32, p3-9] through a range of long-form theoretical responses considering aspects of Australian art.

Sue Best uses the Art and Nature theme to discuss why the work of Sydney women installation artists (Joan Brassil, Joan Grounds, Robyn Backen, Joyce Hinterding, Anne Graham, Simone Mangos, Janet Lawrence) has persuaded her “that installation is the artistic form or practice most suited to a reconsideration of our environment.” In “Artful protest,” Julia Jones explores the potential for art as activism through an examination of environmentalist actions in Australia and beyond.

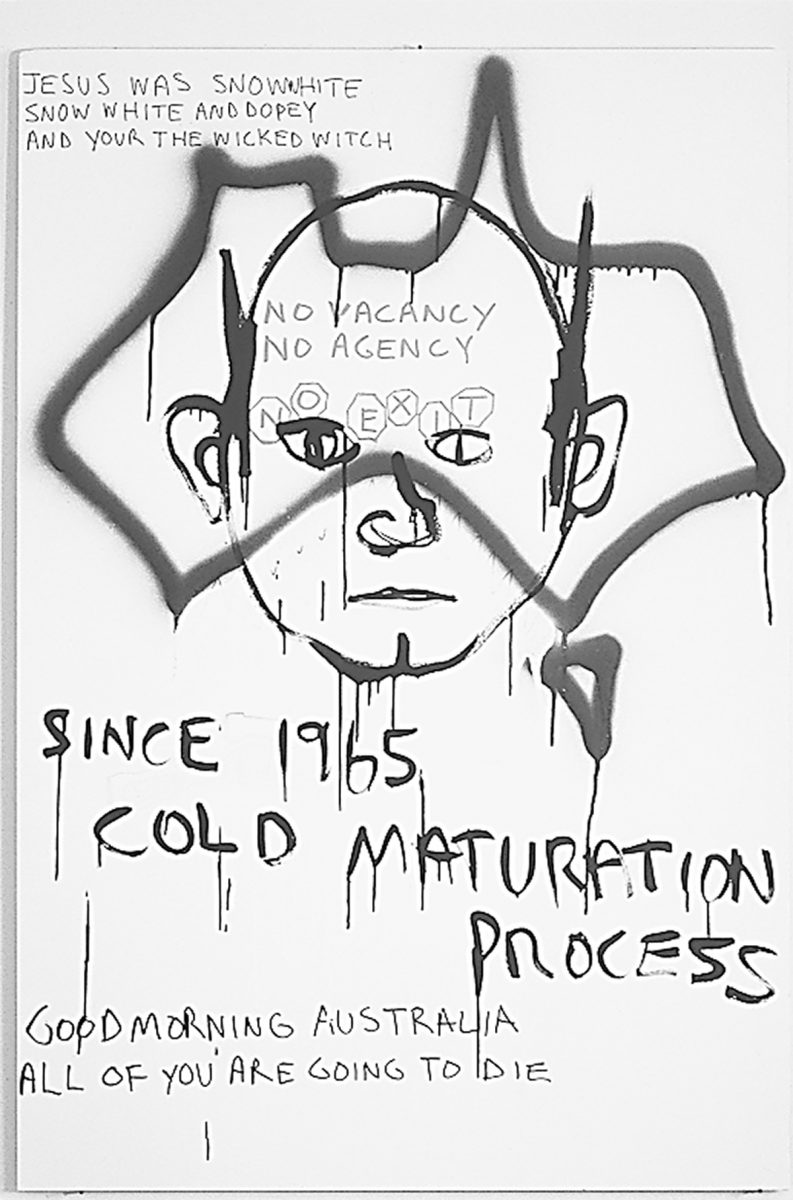

Art and Politics elicited a number of disapproving responses to its theme, which was seen as tautological and a reflection of the lack of self-awareness characterising much Australian culture. Adam Geczy articulates the main concerns in “Art and politics: a tautology” [RT 32, p 4]:

“We forget that art is about giving recognition to a sensibility, that it is about ownership of a history – although Aboriginal art in general is highly cognisant of this. Art is about resistance, it salvages something that would otherwise have gone unnoticed or forgotten.”

“My real concern with the theme for this year’s Perspecta is that it reflects the torpid face of Australia’s arch-liberalism (attacks on the present government notwithstanding), for it turns politics into an option, instead of the epicentre of art’s vitality.”

Art and politics are intertwined in RealTime’s extensive onsite coverage of the third Asia-Pacific Triennial: “Beyond the Future” at Queensland Art Gallery in 1999 [Feature: RT @ APT3 & MAAP99, RT 34, p 20-24]. The collection of 15 reviews are a wonderful example of the way RealTime partnered with festivals to produce detailed, on-the-ground reporting that gave a sense of the character and shape of an event. Virginia Baxter’s review offers a window onto Small Worlds, the APT’s opening event – a panoply of spectacle, ritual and protest art, offering “another kind of geography” where installations from different regions are placed shoulder to shoulder, creating unexpected dialogues.

“Gordon Bennett’s powerful totems glance sidelong at Jun-Jieh Wang’s pink neon Urlaub. Within the sites of Katsushige Nakahashi’s crashed fighter plane made of 10,000 photographs, Xu Bing’s silkworms slowly spin.”

Baxter conjures an experience both exhilarating and troubling, given grim references in many artworks to oppressive conditions in their creators’ countries of origin.

In their assessment of APT3, Going Glocal, Jo Holder and Catriona Moore note various strands of political comment, though in some cases the message is minimised through poor placement, or “that curious re-separation of form and content, spectacle and information that characterises many contemporary art events.” There are critiques of globalisation and cultural commodification, a “cautious re-writing of the Universal Exhibition’s legacy of an idealist (though historically imperialist) space of communication across cultures,” and “Indonesian installations dealing with organised violence and militarism.”

At a critical moment when East Timorese were being massacred during the struggle for independence against Indonesian occupation, however, Holder and Moore feel the festival lost an opportunity to make a stronger statement in protest at Australia’s inaction: “This APT is long on artistic creativity but short on political imagination.”

As was evident in the APT coverage, RealTime was attuned to both celebratory aspects and complexities of the manifold cross-cultural conversations happening on the festival and exhibition circuit. Exhibitions and symposia on Indigenous Australian art (both traditional and contemporary) were documented, migrant experiences were shared, and the flourishing of Asian contemporary art was given serious attention.

Indigenous visual art vs the canon

RealTime’s coverage of Indigenous visual art in the 1990s reveals a dynamic, multifaceted body of work encompassing the increasing prominence of Indigenous contemporary artists and nuanced contextualisation of traditional forms. Exhibitions and articles looked at copyright issues, protocols, commercialisation, women’s artistic practices, political satire, appropriation and, of course, the impact of colonialism.

As part of the 1998 Festival of the Dreaming, Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art mounted two historically significant exhibitions: Bark Paintings from Yirrkala and Tiwi Prints: A Commemorative Exhibition 1969-1996. The June-July RealTime contains an edited transcript of a talk given by Djon Mundine (former Senior Curator at the MCA) in connection with the exhibitions [We are not useless, RT 25, p 4-5]. It’s a standout piece tracing the intertwined histories of bark painting at Yirrkala and the land rights struggle that culminated in the 1976 Land Rights Act in the Northern Territory. Mundine goes on to chart the impact of missionaries, the Australia Council and tourism on the Aboriginal art “industry” and Indigenous fine art, including pressure to produce saleable “suitcase art”. The Yirrkala and Tiwi exhibitions however signal a return to large-scale abstraction, in paintings and prints that Mundine presents as powerful evidence of Indigenous culture’s enrichment of Australian life.

No less vital, though less conciliatory, are the works in Black Humour, an exhibition of Indigenous satirical art reviewed by Cate Jones in the same year [Distinctly Black, RT 26, p 49]. Paintings by Gordon Hookey and Harold Wedge lampoon the Howard Government and Pauline Hanson, as does the Campfire Group’s installation representing a Pauline Hanson fish and chip shop with “crumbed aboriginal artefacts” on the menu.

In the wake of September 11, Suzanne Spunner reports on a week of Indigenous-focused visual arts events in Darwin, including the NATSIAA Aboriginal Art Award as well as a forum organised by 24HR Art at NTU on “Criticism and Indigenous Art, or Sacred Cows and Bulls at the Gate” [Darwin: Hot enough for ya? RT 46, p 10]. Here, speaker Djon Mundine problematises the very action of attempting to interpret Indigenous art through a Western critical lens, insisting that, “until Western art critics learnt Warlpiri as routinely as they might learn French, there can be no real progress in their understanding of Indigenous art.”

“Mundine raised the difficulties of situating the subject amid the territorial imperatives of the two great houses of academe, Anthropology and Fine Arts, and argued that most Indigenous art doesn’t fit the canons of Western art, and to talk in a colloquial style smacks of colonialism and simplification, and to be a Modernist or Post-Colonialist tends to lead to mere comparison viz Aboriginal Cubism and other nonsenses.”

Post-2001, RealTime looked increasingly to emerging multidisciplinary and new media practitioners like r e a (whose work had appeared on the cover of RT 3 and on p 8 and in RT 52, p20], Christian Bumbarra Thompson [RT 52, p 20] and Brook Andrew [RT 54, p 28], recently appointed Artistic Director of the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, the first Indigenous Australian artist to assume the role.

The range of authoritative voices responding to visual art for RealTime gave a clear and compelling sense of the wider conditions influencing the scene in Australia around the turn of the millennium. Perhaps because writers generally worked within the visual arts community, as practising artists, academics and administrators, a strong current of advocacy comes through; a belief in the value of the visual arts ecology at an inimical time.

–

Part 2 of this overview will expand on complex cross-cultural conversations that arose from the wide field of contemporary Asian art, and will look at three multifaceted mediums that captured the zeitgeist: photography, video art and painting.