HKIFF: Fantasy, pain and profit

Mike Walsh

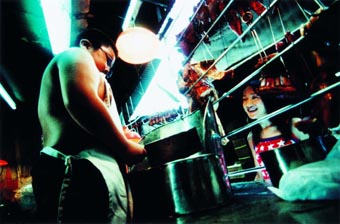

Film still from Hollywod Hong Kong (directed by Fruit Chan)

You can’t sum up a festival like Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) in a short space. Better to mark out a few current questions and suggest ways the films help us think them through. While HKIFF is under pressure to maintain its position as a leading Asian showcase, there is so much to be discovered about Asian cinema that one could happily spend several festivals playing catch up.

Every year we ask the same questions of Hong Kong’s commercial cinema: are the glories in the past, and/or is it about to take over the world? This year’s key exhibit is Stephen Chiau’s Shaolin Soccer. It’s been snapped up by Disney, and while some Canto-fans find it too internationally accessible, what could be more central to Hong Kong than the search for fresh combinations of saleable popular elements? Here the mix involves splicing together soccer, kung fu and digital effects. As the program notes point out, “martial arts fiction has been a powerful tool with which the Cantonese people deal with modernity.”

The most impressive Hong Kong film (and winner of the FIPRESCI Prize) was the animated feature My Life as McDull. It uses diverse animation styles and cute Hello Kitty type figures to contemplate the way bullshit about the magic of childhood leads to an adult life of quiet disillusion. It’s a strongly local film, but also a fresh take on what lies beyond the end of freshness.

While Hong Kong’s art cinema was represented primarily by an Ann Hui retrospective, the most interesting achievement was Fruit Chan’s Hollywood Hong Kong. Chan’s movies always stem from such obviously good ideas. In the most incisive architectural juxtaposition since Psycho, this film brings together new high-rises (felicitously named Hollywood Apartments), with the shantytown at their base. The story deals with a prostitute and a family of fat men who sell pork. Flesh—source of fantasy, pain, and profit—constitutes us and keeps us weighted to the ground. The symbolism in the title marks out an opposition that structures contemporary life: the world of transnational consumer fantasy and the physical, historical world.

If a major theme in Asian cinema is the disparate pulls of past and present, the festival exemplified this with its Cathay studio retrospective. Chief attraction here was the 1960 musical, Wild, Wild Rose with Cathay’s main star, Grace Chang, as a nightclub chanteuse. You can trace a straight (though broken) line back to the 1930s Shanghai melodramas of Ruan Lingyu, where the strong, fallen woman throws it all away for some weak-chinned guy, not man enough to recognise the magnificence of her degradation.

Grace Chang was all over this retrospective. How can a musical called Mambo Girl not be great? Grace has the moves and the knitwear. She concentrates on the stylish shuffle sideways rather than the Great Leap Forward. She mambos and cha-chas through a digressive story that includes visits to nightclubs to watch acts like ‘Margo the Z-Bomb.’ Is it fanciful to imagine a print of this film finding its way into Mao and Jiang Qing’s compound, and in their horror, the seeds of the Cultural Revolution are sown?

Cathay’s comedies, such as The Battle of Love, Sister Long Legs, and Our Dream Car are full of stylish young things with new, western commodities. You might need a neo-realist film to clean your palate afterward, but they mark an important claim by the Chinese for a right to the conspicuous consumption that was for so long the prerogative of the coloniser.

Mainland Chinese films are also grappling with rapid socio-economic transformation right now. Several dealt with economic migrants to the cities, employing a style I’ll call International Chinese Realism (none of these films will probably be shown in China) comprising grubby settings, long takes, minimal non-diegetic sound with the atmosphere track brought forward in the mix. The characters are always cold, and the main reason they go to bed together is to get warm. Wang Chao’s The Orphan of Anyang was the highlight of this group with its minimalism and bold angular compositions. It builds strong intimacies out of long moments in which characters silently share noodles.

As Asian youth culture increasingly looks towards Japan, you wonder whether the Japanese are up to the job. This year’s innovation is the ennui of young Japanese. We know the straight world is boring, but now rebellion is boring too. Toyoda Toshiaki’s Blue Spring is a postmodern Zero de Conduite, taking schoolkid cool almost to a point of catatonia, and the title of When Slackers Dream of the Moon tells you all you need to know.

Suwa Nobuhiro’s H Story similarly abandons narrative as an endeavour too weighty for these times. It starts as the record of an attempt to remake Hiroshima Mon Amour. It’s a clever conceit: a film about the making of a film which is a remake of an earlier film about the making of a film. More an exercise in the failure of signification than a comment on it, the film has to be endured, but it repays the effort through its subversion of any certainties about cinema.

Korea was the breakthrough cinema last year, seizing half of its domestic market, so it was disappointing to see so few Korean films at the festival. Kim Ki-duk, the focus of Melbourne’s retrospective this year, had international success with The Isle. His heavily allegorical Address Unknown confirms the way Kim builds his films around characters in impossible positions. The only options are to re-imagine the world or to destroy yourself, and ultimately the maintenance of the social order relies on the way we find it easier to grasp the second option.

While there were important political films such as Tahmineh Milaneh’s The Hidden Half, the best of the new Iranian films returned to the territory of childhood. Abolfazl Jalili’s Delbaran is a triumph of bold simplicity about a young Afghan boy who works as a gofer in an Iranian border town. It is a celebration of those who keep things running in a world which constantly breaks down. It is a cinema of long takes, simply designed performances, golden light and gentle humour.

Tsai Ming-liang’s What Time Is It There? closed the festival. Like Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang, Tsai is a minimalist, but a minimalist who wants to be liked. While he uses long takes to explore time and space, he ultimately wants to make his characters readable in terms of psychological pathologies. The characters act out cleverly constructed scenarios of loneliness, grief and alienation while the tone resolves into one of cruelty.

Finally, why should we be interested in Asian film? One answer is that we watch films for the pleasure of learning something new, both about cinema and about the world. For a country whose cinema has so few options open to it, Australians should appreciate the formal and industrial diversity of Asian cinemas.

Hong Kong International Film Festival, March 27 – April 7

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 14