I have to live, at least until the plague gets me

Lissa Mitchell

Kate Murphy, Britney Love

Welcome to postmodernism, where without regular excursions into the outdoors, artists have fallen prone to a pestilent force other than nature. Stylistically the artists in ::contagion:, an exhibition of Australian work, are a generation raised on globalised visual culture imported via the television; their work representing what they have ‘seen.’ Curator Linda Wallace describes these artists as using media forms as ‘the machine’ for reprocessing images into art—a form of time machine.

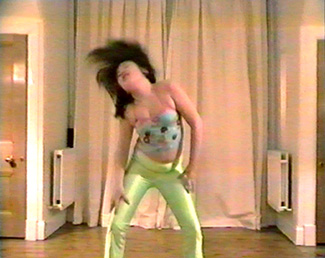

Kate Murphy’s Britney Love, uses television style as performance. Displayed on 6 floor monitors, in pop-girl/boy group formation, an 11-year-old from Glasgow makes public a private performance derived from watching similarly styled performances on television. Britney Love has provoked strong responses from viewers, some taking issue with the artist’s apparent abuse of power over a minor. While Murphy, with her access to a camera might have been in a position of power, the child is (despite the probability of retrospective embarrassment) manufacturing a dream legitimised by watching television. That this idea comes from a mainstream form is a good adjunct to the notion of pedophiles lurking in the dark recesses of the net waiting to snap up innocent children. Artistic vision was once considered to be representative of society in general. A work like Murphy’s throws the modernist concept of the uniquely individual artist back in the face of the viewer.

New media exhibitions pose some prickly questions; like how ‘new’ does media need to be and is copying onto new technologies muddying the waters? Without advocating any tardy purity of materials, just how ‘new’ is PhotoShop? Perspectives on technology are momentarily focused on the newest, raising the issue of how an art of new media might fare. In some senses, ‘new media’ shows how much art appreciation involves backtracking away from literal meaning. Audiences to new media exhibitions might arrive with the expectation of finding ‘self-absorbed’ video or cinematic SFX displays but are dumbfounded when confronted with the likes of Vivienne Dadour’s, Realm, a paper-based text and photographic work. After all, Realm, in reproducing colonial government texts on controlling non-British immigrants, and utilising such passé media as paint, is the stuff of most, plain flavored, contemporary art shows. Meanwhile Matthew Riley’s Memo, presented on CD-ROM, has the look and feel of a picture book. In this way, ::contagion:: takes the approach that ‘nothing’ is ever really ‘new’; that ‘new’ is firmly grounded in the processes of the ‘old.’

In Artist, Tracey Moffatt & Gary Hillberg edit together an exposé of ‘the artist’ sampled from films and reassembled in a sequence that mimics traditional cinematic narrative structure; beginning (creation), middle (reception) and end (destruction). The artist in popular culture is a pathetic figure; their desire to represent does not have a contagious effect on the general populace. In the examples re-used by Moffat & Hillberg, artist and audience ultimately react violently towards aspirations for the ‘new’–whether stylistic and/or technological. Wallace’s own work, eurovision, re-uses imagery from film and television to re-use ideas within a contemporary context; it may be ‘new’ media but the how and what of representation still plagues artists. These works are poignant examples of how visual sampling can work. The hunger to represent despite technological change remains (whether paint brush, digital video or source code).

With the physical space showing paper-based work and using video, monitors and projection, as a screening format, the online content is where ::contagion:: ‘feels’ digital. Sites gathered here as ‘webworks’, such as subtle.net and laudible.net, show how current new mediums broaden the scope of art into wider issues of communication and broadcast. On laudible.net, the work of sound artists forms an archive of mock webcasts. These sites raise art appreciation to a new level, visually advocating technological formalism and inviting critiques of programming styles. This contrasts with the work of Gary Foley’s; here accessibility is both a visual and political strategy. The use of technology and the design of the site aim at a wide audience. In ::contagion::, these sites are a survey of Australian web activity over the past five years.

Just one quibble to finish, if Koori artists are not hooking into current urban and net-based new media communities curators could be meeting these artists on their own ground. If reconciliation is to be addressed, is this not be part of making it happen?

–

::contagion:: Australian Media Art @ the Centenary of Federation, curated by Linda Wallace, The Film Centre Wellington, Oct-Nov.

RealTime issue #46 Dec-Jan 2001