Indian art: wit and politics

Bec Dean

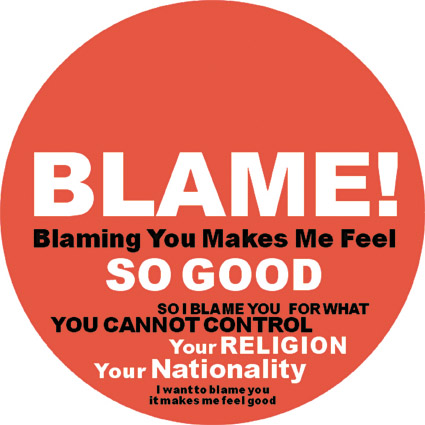

Shilpa Gupta, Blame, 2003

Jayalitha is a smoky-eyed mistress of the lash. Whip toting and dressed like a man, she is clad in black from head to toe with a belt of knives around her waist. Whether she is a huntress, a stealthy liberator or an agent of vengeance, I can’t quite translate. She stands casually and assertively against the painted backdrop of a domestic interior, ready and waiting. Pushpamala N and Clare Arni’s collaborative photographs, Native Women of South India: Manners and Customs Series is the first work encountered on entering the ground-floor gallery space of Edge of Desire: Recent Art in India at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA). As an entrance statement, their work clearly sets the tone for this survey of 37 artists from across the country. Pushpamala N and Clare Arni combine a clever, staged critique of ancient Indian customs against the introduced classification systems of colonial times, while referencing the format of early studio-based photography. Native Women of South India engages in the politics of power, sexuality, tradition, religion and caste—prevalent themes throughout the exhibition.

Surendran Nair’s large-scale painting, Mephistopheles…otherwise the quaquaversal prolix (cuckoonebulopolis) (used as the promotional image for Edge of Desire) is one of the most sinister and unnerving works in the show, depicting the stylised form of a man levitating in a yoga position. His face is elaborately and beautifully masked while the fingers of his left hand form the sign for silence against his mouth. His right hand morphs into a pistol and he wears a severed tongue on a necklace. Mephistopheles is presented by Nair as the thirteenth sign of the zodiac, following his smaller watercolour series Precision Theatre of the Heavenly Shepherds, an apocalyptic symbol of deceit exacting both censure and violence.

Upstairs, Nalini Malani continues this line of enquiry with her light-based installation The Sacred and the Profane. Her paintings of gods and monsters made with synthetic polymer on large, rotating mylar cylinders have seen some exposure in Australia through the Queensland Art Gallery’s Asia Pacific Triennial in 2002. When back-lit her images become animated and intermingle on the back wall in an orgy of worship, sex and death, all inextricably linked.

A video self-portrait by Sonia Khurana entitled Bird shows the artist—an overweight, middle-aged woman—naked and pushing her body around in an uncoordinated dance, testing the limitations of her physicality. The video speed is also pushed and fed through a digital filter so that her body becomes less sexualised and more cartoon-like. While the computer-generated solarisation is tacky and cheap, watching Khurana spinning out of control with jerky little leg extensions, almost falling over and rolling round on the floor is mesmerising and hysterically funny.

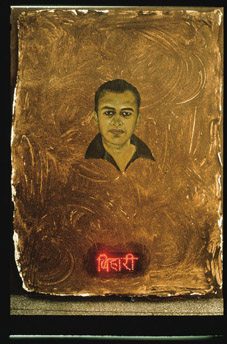

Subdoh Gupta, Bihari, 1998

Likewise, the self-effacing humour of Subdoh Gupta sees the installation artist representing himself as both erotic and abject figure. In the photograph Vilas he is naked and smeared all over with Vaseline, slouching resplendent in a green leather chair. In Bihari he has painted an image of himself surrounded by actual cow dung with a flashing neon light. ‘Bi Ha Ri’ is the name of the poor town he was born in, and also a vernacular phrase used by Indians to imply stupidity. The works of Khurana and Gupta tackle conventional and accepted modes of behaviour, and in Gupta’s case the transcendence of class.

Artists manipulating traditional artforms and crafts to critique contemporary issues include NS Harsha and Sharmila Samant. Harsha’s large-scale drawing in green ink, For you my dear Earth, is about 10-15 metres long and divided into 3 parts. Intersecting the middle is a panel of gold leaf from which the dainty, botanical drawings of plants and flowers on either side begin to sprout. As the drawing extends, the plant forms become larger and more unruly, incorporating introduced species and gradually evolving into monstrous looking, Day of the Triffids-style blooms. Sharmila Samant’s A Handmade Sari, made from rusted Coke and Diet Coke bottle tops, incorporates the traditional mango motifs that appear on many Indian fabrics. While each of the works is aesthetically stunning, both artists interrogate the effects of globalisation on the environment and the cultural economy of India respectively. On the way out of the exhibition, Dayanilta Singh’s framed portraits of political and spiritual leaders in-situ in people’s homes and work environments remind one of the omnipresent politics and political thinkers in India’s population. It’s hard to imagine Australians choosing to wake up to the uninspiring likeness of John Howard.

Outside the gallery, in the lead-up to the exhibition opening, Shilpa Gupta re-staged a performance inviting us all to “use blame—feel good” by handing-out free samples of a new product, BLAME! as a remedy to the world’s problems. These small bottles of red liquid were installed inside the exhibition on shelves, and lit by red fluorescent tubes like luxury cosmetics set against a video promoting the product. Shilpa’s previous work includes the fabrication of candy kidneys and an installation representing a designer store for the trade of human body parts. She critiques the cultures of discrimination, commodification and power that effect both Indian society and the global culture at large. (For more on Shilpa Gupta see page 27.)

Installed on 2 levels of AGWA, and travelling straight from Perth to New York, Edge of Desire is diverse in its selection of artists, and is contemporary in the broadest sense of the word. As a survey, the exhibition has its share of overtly didactic and poorly resolved pieces, but these are countered by the work of some of India’s finest contemporary practitioners. With such a broad scope, the exhibition should have been teeming with visitors, but was rendered quiet by a prohibitive ticket price that left most punters hovering on the edge. Outside the exhibition, and appropriately close to the exhibition store, the Paan Beedi Shop was one of the only works made accessible to the non-paying public. Literally an uprooted stall selling such everyday items as cigarettes, sweets, incense and biscuits, the shop’s keeper was replaced by a recessed monitor repeating an endlessly entertaining selection of video-fillers from MTV India. With a plethora of history and tradition to lampoon, these shorts by Cyrus Oshidar take off everything from Bollywood dance sequences and cheesy Indian pop stars to the simultaneously painful and relaxing, all inclusive hair-cut at an Indian barber’s shop.

Edge of Desire, curator Chaitanya Sambrani, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, Sept 25 2004-Jan 9 2005

RealTime issue #65 Feb-March 2005 pg. 8